Abstract

To confirm circulation of Anajatuba virus in Maranhão, Brazil, we conducted a serologic survey (immunoglobulin G ELISA) and phylogenetic studies (nucleocapsid gene sequences) of hantaviruses from wild rodents and persons with hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. This virus is transmitted by Oligoryzomys fornesi rodents and is responsible for hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in this region.

Keywords: Hanvavirus pulmonary syndrome, hantavirus, Anajatuba virus, Oligoryzomys fornesi, Brazil, viruses, zoonoses, dispatch

Hantaviruses (family Bunyaviridae, genus Hantavirus) cause a viral zoonosis transmitted by rodents belonging to the families Muridae and Cricetidae. Each hantavirus is predominantly associated with a specific rodent species in a specific geographic region. However, infection of other rodent species can occur as a spillover phenomenon (1).

Hantavirus disease has 2 recognized clinical forms, hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) (2). The respiratory form of the disease was described in June 1993 during an epidemic of severe respiratory disease caused by Sin Nombre virus in the United States (3). A few months later, 3 HPS cases were identified in 3 siblings in Juquitiba, São Paulo State, Brazil (4). During 1993–2009, a total of 1,246 HPS cases (264 in the Amazon region) were reported in Brazil, and new hantaviruses were identified (Juquitiba virus, Castelo dos Sonhos virus, Araraquara virus, Anajatuba virus, and Rio Mearim (5).

During 2003–2005, an ecoepidemiologic study was conducted in the municipality of Anajatuba, Maranhão, Brazil, to identify reservoirs of hantaviruses after identification of 3 HPS cases (6). Two new hantaviruses, Anajatuba virus and Rio Mearim virus, were isolated from Oligoryzomys fornesi (rice rat) rodents and Holochilus sciureus (marsh rat) rodents, respectively, and genetically characterized (5). To confirm circulation of Anajatuba virus in Maranhão, Brazil, we conducted a serologic survey (immunoglobulin [Ig] G ELISA) and phylogenetic studies (nucleocapsid gene sequences) of hantaviruses obtained from wild rodents and persons with HPS.

The Study

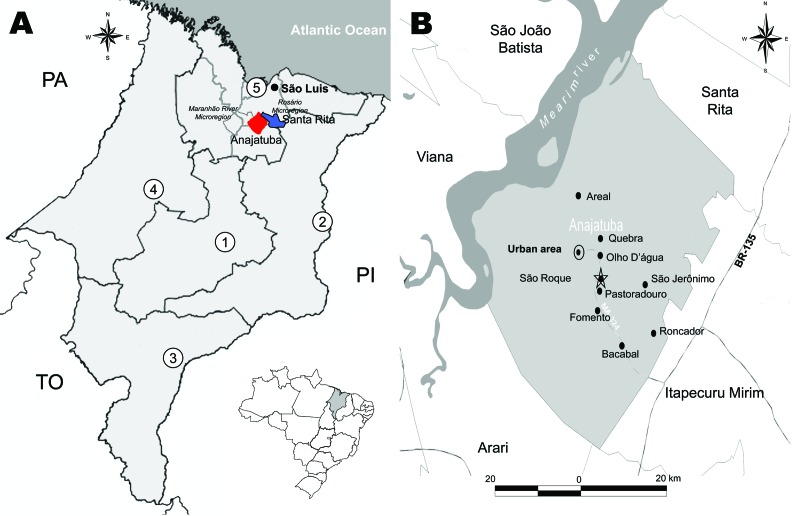

Anajatuba (3°16′S, 44°37′W; population 23,907) and Santa Rita (3°9′S, 44°20′W; population 31,033) (www.ibge.gov.br), are located in the western floodplain of the Maranhão River in Maranhão State, Brazil (Figure 1, panel A). The region has chains of lakes with extensive swamps and flooded fields, forest areas, and rice fields extending from the outskirts of the urban area. The climate is tropical and humid (average temperature range 26°C–28°C), and the rainy season is during January–July (5,6).

Figure 1.

A) Regions of Anajatuba (red) (Maranhão River Microregion) and Santa Rita (blue) (Rosario Microregion), Maranhão, Brazil, where hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) cases were found. PA, Para; TO, Tocantins; PI, Piaui; 1, central region; 2, eastern region; 3, southern region; 4, western region; 5, northern region. B) Towns in Anajatuba where a serologic survey for HPS in humans was performed. Dotted oval, São Roque; star, rodent capture location; ovals, locations where HPS cases were found.

Data for 5 cases of HPS in men (age range 25–30 years, 3 from Anajatuba and 2 from Santa Rita) are shown in Table 1. In a cross-sectional serologic survey in residents of Anajatuba, 293 serum samples (8.1% of the population studied and 1.2% of the total population of the municipality) were obtained; 153 (52%) residents were women. Fifty-four samples were obtained from urban residents, and 239 samples were obtained from rural residents. All samples were tested by using an ELISA to detect IgM and IgG as described (7).

Table 1. Characteristics of 5 human case-patients with hantavirus pulmonary syndrome and 3 rodents infected with hantavirus, Maranhão, Brazil*.

| Sample origin† | Municipality/town | Patient age, y | Sample collection date | Symptom duration, d | Clinical outcome | ELISA results |

GenBank accession no. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG | IgM | |||||||

| Human | ||||||||

| Be H 666379‡ | Anajatuba/São Roque | 24 | 2003 Mar 25 | 1 | Died | Neg | Pos | HM238889 |

| Be H 668281 | Santa Rita/Conceição | 21 | 2003 May 14 | 6 | Recovered | Pos | Pos | – |

| Be H 670957‡ | Anajatuba/Fomento | 24 | 2003 Jul 22 | 4 | Recovered | Pos | Pos | HM238890 |

| Be H 672862‡ | Santa Rita/NA | 39 | 2003 Oct 21 | 10 | Recovered | Neg | Pos | HM238885 |

| Be H 708080 |

Anajatuba/Roncador |

28 |

2006 Jun 12 |

NA |

Died |

Neg |

Pos |

– |

| Rodent | Species |

|||||||

| BeAN669104‡ | Anajatuba/São Roque | NA | 2003 May 27 | Necromys lasiurus | Pos | ND | HM238886 | |

| BeAN690936‡ | Anajatuba/São Roque | NA | 2005 May 18 | Oligoryzomys fornesi | Pos | ND | HM238887 | |

| BeAN690985‡ | Anajatuba/São Roque | NA | 2005 May23 | O. fornesi | Pos | ND | HM238888 | |

*Ig, immunoglobulin; Neg, negative; Pos, positive; NA, not available; ND, not done. †Serum samples were obtained from humans (males), and lung tissue samples were obtained from rodents (males). ‡Amplicons for these samples were sequenced.

The main findings of the serologic study are shown in Table 2. A male:female ratio of 2:1 was observed in urban and rural areas. Factors investigated for increasing risk for exposure to hantaviruses included living near rice paddies; engaging in farming or fishing; having wild rodents around the household; having contact with wild rodents in the workplace, school, or domestic surroundings; and storing rice in the household.

Table 2. Testing for hantavirus among residents of urban and rural areas of Anajatuba, Maranhão, Brazil, May 2005*.

| Zone | Town | Total population | No. (%) persons sampled | No. (%) persons positive† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban |

Limirique and Porção do Junco (neighborhood) |

1,059 |

54 (5.09) |

9 (16.7) |

| Rural | Areal | 375 | 42 (11.2) | 3 (7.1) |

| Bacabal | 790 | 57 (7.2) | 7 (12.3) | |

| Olho d’água | 193 | 51 (26.4) | 5 (9.8) | |

| Quebra | 584 | 38 (6.5) | 5 (13.2) | |

| São Roque and Pastoradouro | 634 | 51 (8.0) | 3 (5.9) | |

| Rural zone total |

2,576 |

239 (9.3) |

23 (9.6) |

|

| Total | 3,635 | 293 (8.1) | 32 (10.9) | |

*Data were provided by the Health Municipal Secretary of the Anajatuba Municipality, 2005. †By immunoglobulin G testing.

In May 2003 and May 2005, two rodent captures approved by the Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis/Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade were conducted in São Roque, Anajatuba (Figure 1, panel B). Trapping was conducted <50 m from residences of 3 deceased HPS case-patients in accordance with accepted rodent capture and handling procedures and standard biosafety protocols for anesthetizing and killing rodents, and biometric analysis was conducted (8). Fragments of liver, lung, spleen, heart, and kidney were obtained. Taxonomic identification was performed according to procedures of Bonvincino and Moreira (9).

Biologic samples (blood and viscera fragments) were obtained from 216 captured rodents: 96 (44%) captured in 2003 and 120 (56%) captured in 2005. The most common species captured in 2003 were Necromys lasiurus rodents (n = 62, 64%) and Akodon sp. rodents (n = 27, 28%). The most common species captured in 2005 were N. lasiurus rodents (n = 105, 87%) and O. fornesi rodents (n = 2, 2%); the remaining rodents were from other genera.

Blood samples collected from wild rodents were also tested by using an IgG ELISA (10). IgG against hantavirus was detected in 2 (100%) of 2 O. fornesi rodents captured in 2005 and 6 (4%) of 167 N. lasiurus rodents (3 of 62 captured in 2003 and 3 of 105 captured in 2005) (Table 1).

Virus RNA was extracted from IgM-positive human serum or blood samples and lung fragments from IgG-positive rodents by using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Nested reverse transcription–PCR and hemi-nested reverse transcription–PCR were used for amplification of partial nucleocapsid gene sequences from human and rodent samples, respectively, by using primers described (11). Purified amplicons were obtained by using the GFX PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit (Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) and sequenced. Amplicons (434 bp) generated from HPS cases in humans (2 from Anajatuba and 1 from Santa Rita) and from 3 of 8 lung samples from hantavirus IgG-positive rodents were sequenced (Table 1).

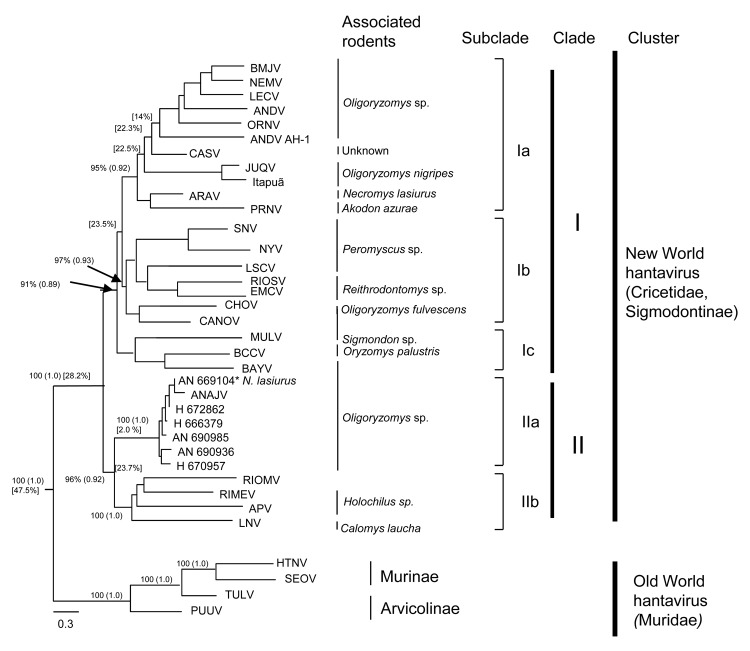

Phylogenetic trees were constructed by using neighbor-joining, maximum-parsimony, maximum-likelihood, and Bayesian methods implemented in PAUP 4.0b.10 (12), PHYML (13), and BEAST (14). Modeltest version 3.6 (15) was used to determine the best nucleotide substitution model based on Akaike information criteria. Analyses were conducted by using confidence values estimated from mean nucleotide divergence obtained for different Old World and New World hantavirus sequences by using MEGA version 3.0 software (www.megasoftware.net) Estimated values were <45%, <25%, 22%, and 15% and were used for grouping viruses in clusters, clades, subclades, and species, respectively.

All phylogenetic methods showed similar topologies, and the ML maximum-likelihood construction was selected for representing the final tree. Bootstrap and Bayesian posterior probability values are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of partial small RNA segments of hantaviruses, Maranhão, Brazil, by using maximum-likelihood and Bayesian methods. Bayesian and bootstrap values (in parentheses) are shown over each main tree node. Values in brackets indicate mean divergence between groups. Arrows indicate exact position of these 2 values. Scale bar indicates nucleotide sequence divergence. BMJV, Bermejo virus; NEMV, Neembuco virus; LECV, Lechiguanas virus; ANDV, Andes virus; ORNV, Oran virus; CASV, Castelo dos Sonhos virus; JUQV, Juquitiba-Araucaria virus; ARAV, Araraquara virus; PRNV, Pergamino; SNV, Sin Nombre virus; NYV, New York virus; LSCV, Limestone Canyon virus; RIOSV, Rio Segundo virus; ECMV, El Moro Canyon virus; CHOV, Choclo virus; CANOV, Cano Delgadito virus; MULV, Muleshoe virus; BCCV, Black Creek Canal virus; BAYV, Bayou virus; ANAJV, Anajatuba virus; RIOMV, Rio Mamoré virus; RIMEV, Rio Mearim virus; APV, Alto Paraguay virus; LNV, Laguna Negra virus; HTNV, Hantaan virus; SEOV, Seoul virus; TULV, Tula virus; PPUV, Puumala virus.

Two major clusters were observed (New World and Old World hantavirus groups) and had a genetic distance of 28.2% (inclusion value 25%). The New World group was divided into clades I and II. Clade I was divided into 3 subclades (genetic divergence 23.5%), Ia, Ib, and Ic. Clade II was divided into 2 subclades (genetic divergence 23.7%), IIa and IIb. The strains used in this study were closely related to Anajatuba virus and were included in the IIa subclade (genetic divergence 2%) (Technical Appendix ).

Nucleotide and amino acid homology between Anajatuba virus (5) and the strains isolated in this study in Maranhão were 98.3% and 100%, respectively. These strains were included in a group related to rodents belonging to the genus Oligoryzomys, although sample Be AN 669104 was obtained from an N. lasiurus rodent, which suggests spillover transmission between rodent species.

Conclusions

We showed that Anajatuba virus is responsible for human HPS cases and that O. fornesi rodents are its likely reservoir. Anajatuba virus infections of N. lasiurus were spillover infections. Human hantavirus infections are common among persons in the Baixada Maranhense region, but cases of HPS are rare. However, educational and health surveillance programs are needed to prevent hantavirus transmission.

Supplementary Material

Distribution of hantavirus groups and subgroups in the Western Hemisphere.

Acknowledgments

We thank Osvaldo Vaz, Mário Ferro, Samir Casseb, Helena Vasconcelos, Olinda Macedo, Adriana Ribeiro, the Anajatuba Municipal Health Secretary, the Maranhão Health Secretary, and the Secretary of Health Surveillance for assistance.

This study was supported by grants INCT-FHV-573739/2008-0, 300460/2005-8, and 302987/2008-8 from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnologico and grants SECTAM/FUNTEC/EDITAL, PPRH 2003 CT, and IEC/SVS/MS from the Pará State Secretariat for Science, Technology and Environment.

Biography

Dr Travassos da Rosa is senior researcher in the Department of Arbovirology and Hemorrhagic Fevers at Evandro Chagas Institute, Ananindeua, Brazil. Her research interests are diagnosis, epidemiology, and molecular epidemiology of arboviruses, hantaviruses, and rabies virus.

Suggested citation for this article: Travassos da Rosa ES, Sampaio de Lemos ER, de Almeida Medeiros DB, Simith DB, de Souza Pereira A, Elkhoury MR, et al. Hantaviruses and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, Maranhão, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2010 Dec [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1612.100418

Deceased.

References

- 1.Milazzo ML, Cajimat MN, Hanson JD, Bradley RD, Quintana M, Sherman C, et al. Catacamas virus, a hantaviral species naturally associated with Oryzomys couesi (Coues’ oryzomys) in Honduras. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:1003–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Childs JE, Ksiazek TG, Spiropoulou CF, Krebs JW, Morzunov S, Maupin GO, et al. Serologic and genetic identification of Peromyscus maniculatus as the primary rodent reservoir for a new hantavirus in the southwestern United States. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1271–80. 10.1093/infdis/169.6.1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nichol ST, Spiropoulou CE, Morzunov S, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, Feldmann H, et al. Genetic identification of a hantavirus associated with an outbreak of acute respiratory illness. Science. 1993;262:914–7. 10.1126/science.8235615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.da Silva MV, Vasconcelos MJ, Hidalgo NT, Veiga AP, Canzian M, Marotto PC, et al. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Report of three cases in São Paulo, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1997;39:231–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosa ES, Mills JM, Padula PJ, Elkhoury MR, Ksiazek TG, Mendes WS, et al. Newly recognized hantaviruses associated with hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in northern Brazil: partial genetic characterization of viruses and serologic implication of likely reservoirs. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2005;5:11–9. 10.1089/vbz.2005.5.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendes WS, Aragão NJ, Santos HJ, Raposo L, Vasconcelos PF, Rosa ES, et al. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in Anajatuba, Maranhão, Brasil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2001;43:237–40. 10.1590/S0036-46652001000400013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson AM, Souza LT, Ferreira IB, Pereira LE, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, et al. Genetic investigation of novel hantaviruses causing fatal HPS in Brazil. J Med Virol. 1999;59:527–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mills JN, Ksiazek TG, Ellis BA, Rollin PE, Nichol ST, Yates TL, et al. Patterns of association with host and habitat: antibody reactive with Sin Nombre virus in small mammals in the major biotic communities of the southwestern United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:273–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonvincino CR, Moreira MA. Molecular phylogeny of the genus Oryzomys (Rodentia: Sigmodontinae) based on cytochrome b DNA sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2001;18:282–92. 10.1006/mpev.2000.0878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padula PJ, Colavecchia SB, Martínez VP, Valle MO, Edelstein A, Miguel SD, et al. Genetic diversity, distribution, and serological features of hantavirus infection in five countries in South America. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3029–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson AM, Bowen MD, Ksiazek TG, Williams RJ, Bryan RT, Mills JN, et al. Laguna Negra virus associated with HPS in western Paraguay and Bolivia. Virology. 1997;238:115–27. 10.1006/viro.1997.8840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swofford DL. PAUP: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony and other methods, Version 4. Sunderland (MA): Sinauer Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guindon S, Gascuel OA. Simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. 10.1080/10635150390235520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drummond AJ, Pybus O, Rambaut A, Forsberg R, Rodrigo A. Measurably evolving populations. Trends Ecol Evol. 2003;18:481–8. 10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00216-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Posada D, Crandall KA. Modeltest: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–8. 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Distribution of hantavirus groups and subgroups in the Western Hemisphere.