Abstract

Theileria parva is a tick-transmitted protozoan parasite that infects and transforms bovine lymphocytes. We have previously shown that Theileria parva Chitongo is an isolate with a lower virulence than that of T. parva Muguga. Lower virulence appeared to be correlated with a delayed onset of the logarithmic growth phase of T. parva Chitongo-transformed peripheral blood mononuclear cells after in vitro infection. In the current study, infection experiments with WC1+ γδ T cells revealed that only T. parva Muguga could infect these cells and that no transformed cells could be obtained with T. parva Chitongo sporozoites. Subsequent analysis of the susceptibility of different cell lines and purified populations of lymphocytes to infection and transformation by both isolates showed that T. parva Muguga sporozoites could attach to and infect CD4+, CD8+, and WC1+ T lymphocytes, but T. parva Chitongo sporozoites were observed to bind only to the CD8+ T cell population. Flow cytometry analysis of established, transformed clones confirmed this bias in target cells. T. parva Muguga-transformed clones consisted of different cell surface phenotypes, suggesting that they were derived from either host CD4+, CD8+, or WC1+ T cells. In contrast, all in vitro and in vivo T. parva Chitongo-transformed clones expressed CD8 but not CD4 or WC1, suggesting that the T. parva Chitongo-transformed target cells were exclusively infected CD8+ lymphocytes. Thus, a role of cell tropism in virulence is likely. Since the adhesion molecule p67 is 100% identical between the two strains, a second, high-affinity adhesin that determines target cell specificity appears to exist.

INTRODUCTION

Theileria parva is an apicomplexan intracellular protozoan parasite that infects and transforms lymphocytes of cattle and African buffalo (Syncerus caffer). Transmitted by Rhipicephalus appendiculatus ticks, the parasite causes a severe lymphoproliferative disease of cattle, called East Coast fever, in eastern, central, and southern Africa. The tick-transmitted sporozoite stage of T. parva is known to bind specifically to target lymphocytes. There is evidence that surface major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules and β-microglobulin are part of the host cell receptor (30), but one antibody to CD45 could also specifically block binding (34). For the parasite, a p67 antigen on the surface of the sporozoite was identified as playing the role of a ligand in adhesion, since antibodies to p67 could inhibit binding and neutralize infection (6, 21). Once inside the cell, the sporozoite differentiates into a multinucleated macroschizont. The capacity of this schizont to transform and divide in synchrony with the host cell leads to rapid clonal expansion of infected host cells and the establishment of continuous cultures of T. parva-infected cells (2) and Theileria-transformed lines.

Bulk infected cell lines obtained from in vivo or in vitro infections of bovine cells with T. parva Muguga belonged to the αβ T cell lineage, with the majority being CD4+ cells (3, 7). However, when limiting dilutions were carried out on fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) or when lymphocytes were purified according to phenotype before in vitro infection, transformed lines of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, γδ T cells, and B cells were obtained (3, 15). Although all T. parva-transformed cells acquired some markers characteristic of a subset of multiplying T cells (24), including a p100 activation antigen and WC14 (25), other markers were lost upon transformation (3). However, cells of different precursor origins retained different phenotypic characteristics, allowing identification of the infected host cell type. In most instances, T. parva-transformed B cells lost expression of surface immunoglobulin but never acquired CD2, CD4, CD6, or CD8, although CD8 or WC1 was sometimes detected on a portion of the cells (3). CD4+ T cells always retained the expression of CD4 and CD2, but not CD6, and sometimes acquired a variable expression of CD8 (3, 7). Using specific reagents, this newly acquired CD8 was suggested to be composed of CD8α homodimers only, not CD8αβ heterodimers (16). Infected CD8+ T lymphocytes retained the expression of CD2 and CD8 but sometimes acquired expression of the γδ T cell marker WC1. On the other hand, WC1+ cells transformed in vitro with T. parva retained expression of the WC1 antigen but acquired expression of CD2 and CD8 on a proportion of the cells. Interestingly, a CD8+ T cell clone infected with different T. parva genotypes differed in expression of the lineage-specific markers CD6, CD8, and WC1 (5), suggesting the possibility that isolates of different genotypes modulate host cell surface marker expression differently.

Recently, we showed that T. parva Chitongo, from Zambia, induced a less severe form of disease than T. parva Muguga, from Kenya (35), after infection with similar doses of infective sporozoites. We ruled out the possibility that Muguga-infected cells multiplied faster than Chitongo-infected cells. One observation that could explain this lack of virulence was that sporozoites from the Chitongo strain took longer to transform bovine lymphocytes in vitro than those of the Muguga isolate (up to 7 days instead of 3 days for the particular cell and sporozoite numbers used in that experiment). However, in vivo, the difference in parasitosis between the two isolates differed by only 1 to 1 1/2 days.

Some studies have shown that the cell type infected by T. parva (19) can influence the pathogenicity of the parasite, although other factors, such as culture conditions of infected cell lines, could have influenced the results. Expression of adhesion molecules and release of immune mediators by particular transformed cell types could influence the pathology of infected animals (11, 32). Therefore, we compared sporozoites of T. parva Chitongo and T. parva Muguga for the capacity to bind, infect, and transform different lymphocyte subpopulations and analyzed the postinfection cell phenotypes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of PBMC and infection with sporozoites.

Isolation of PBMC and infection with sporozoites were carried out as described previously (35). Briefly, blood was collected in Alsever's solution by jugular venipuncture of healthy cattle maintained under tick-free control at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Nairobi, Kenya, and at the Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM), Antwerp, Belgium. PBMC were isolated by flotation on Ficoll (Histopaque at 1.077 g/ml; GE Healthcare) according to standard protocols. PBMC were resuspended in tissue culture medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum [FCS], 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 5 × 10−5 M β-mercaptoethanol) at a density of 3 × 106/ml. Infection with cryosporozoite stabilates was done by mixing the sporozoites with bovine cells, followed by incubation at 37°C for 1.5 h. The infected cells were then washed and cultured.

Sporozoites.

Two cryopreserved sporozoite stabilates were used. The T. parva Chitongo (CA0401) stabilate originated from the Chitongo area in Zambia and consisted of ground-up ticks, while the T. parva Muguga (T. parva Muguga 3087 DSG 4221) stabilate originated from Kenya and was prepared from isolated tick salivary glands (DSG). In all comparative studies using sporozoite preparations, we made sure that we used equivalent sporozoite concentrations. In our previous study (35), we quantified sporozoites by using an in vitro infection assay and found that our T. parva Muguga stabilate contained four times more infective sporozoites than the T. parva Chitongo stabilate. Therefore, we diluted the T. parva Muguga stabilate four times more than the T. parva Chitongo stabilate.

Establishment of long-term ConA-stimulated lymphocytes.

A concanavalin A (ConA)-stimulated lymphoblastoid cell line was established according to the method of Goddeeris and Morrison (10). Purified PBMC were incubated overnight for 18 h. ConA was then added at a concentration of 2.5 μg/ml, and cultures were then split three times every 3 days, with a supplement of supernatant containing recombinant interleukin-2 (IL-2) expressed in baculovirus (1) at a final concentration of 100 units per ml. The line was kept for 3 months, and flow cytometric analysis showed that it was positive for WC1 and CD3 and negative for CD4 and CD8, suggesting that the line was composed of γδ WC1+ T cells.

Sorting of CD4+, CD8+, and γδ WC1+ T cells.

Sorting of cells was done with anti-immunoglobulin (anti-Ig)-coated magnetic beads (MACS; Miltenyi Biotech, United Kingdom) according to the standard protocol recommended by the manufacturer. PBMC were purified by Ficoll-Paque density gradient centrifugation (35). The last wash was done using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS), without Ca2+ or Mg2+, to optimize antibody binding. Aliquots of 1 × 109 PBMC were incubated at 4°C for 30 min with 0.5 ml of a solution of approximately 10 μg/ml of a CD4 monoclonal antibody (MAb) (IL-A12 [IgG2a] or IL-A11 [IgG2a]), a WC1 MAb (IL-A29 [IgG2a]), or a CD8 α chain MAb (IL-A105 [IgG2a] or IL-A51 [IgG1]) (23). For positive selection, cells with attached beads were eluted, washed once, and incubated overnight to shed off or internalize the beads in culture medium at 37°C.

Subpopulations (CD4, CD8, and WC1 cells) were also purified by negative selection. In these cases, purified PBMC were mixed with beads containing antibodies to the other populations, including antibodies against macrophages (IL-A24) and B cells (IL-A30) (23). The unbound fractions were collected and tested for purity by flow cytometry.

Infection of cell populations.

Threefold dilutions were made from the sporozoite stabilates, starting at a dilution of 1/3.3 and going up to a dilution of 1/2,483. The samples were incubated with ConA blast cells or purified CD4+ or γδ T cells for 1 h at 37°C (35). After one wash, cells were resuspended in complete RPMI 1640 culture medium and incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

In the last experiment, CD8+ and CD4+ cells were infected with equivalent sporozoite titers, using 8-fold and 2-fold dilutions for the T. parva Muguga and T. parva Chitongo stabilates, respectively.

Flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry was carried out on a FACScan or FACSCanto flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Erembodegem, Belgium). The MAbs used to identify the different leukocyte populations (23) consisted of IL-A11, IL-A12, or CC30 (bovine CD4 [BoCD4]), IL-A105 or IL-A51 (BoCD8 α chain), CC58 (BoCD8 heterodimer/β chain), IL-A29 or CC15 (WC1 and γδ T cells), IL-A30 (IgM and B cells), IL-A65 (CD21 and B cells), and IL-A24 (monocytes).

Sporozoite binding assay.

Approximately 5 × 106 PBMC or purified cells were incubated on ice for 30 min with sporozoite stabilates of T. parva Muguga 3087 (DSG 4221) or T. parva Chitongo (CA0401), diluted in the range of 1/2 to 1/40,960 via 2-fold dilutions in a total volume of 200 μl. Cells were washed with 200 μl of prechilled (on ice) RPMI 1640 containing 0.1% sodium azide and pelleted at 500 × g for 3 min at 4°C. Sporozoite binding was detected by incubation of the resuspended cells for 30 min on ice with an anti-p67 MAb, either AR22.7 (IgG1) or AR23 (IgG2a) (14, 22, 27), followed by three washes with 200 μl of ice-cold RPMI 1640 with 0.1% sodium azide and incubation for 30 min on ice with 50 μl of either R-phycoerythrin-labeled anti-mouse IgG1 (IgG1-RPE) (1:200; Sigma) or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-mouse IgG2a antibody (1:50; Sigma). Negative controls consisted of cells stained without the addition of sporozoites. Cells with bound sporozoites were measured as fluorescent cells, and a forward/side scatter window on live cells was used to exclude nonspecific staining of dead cells and debris.

Sporozoite binding on γδ T cells which had been purified with an anti-WC1 MAb (IL-A29 [IgG1]) was analyzed with the anti-p67 AR23 MAb (IgG2a) and an FITC- or PE-labeled anti-mouse IgG2a conjugate. The cells were then fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS, and fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry (FACSCanto; Becton Dickinson, Erembodegem, Belgium).

Intracellular staining of Theileria parva-infected PBMC.

Intracellular staining of the schizont antigen PIM in infected PBMC or cells from established T. parva Chitongo- and T. parva Muguga-infected lines was carried out as previously described (28). After staining, cells were fixed in 1% PFA until analysis on a FACScan flow cytometer. For double staining, the cells were stained for leukocyte surface markers (CD4, CD8, and γδ T cell markers) first, followed by 1% PFA fixation before intracellular staining.

Fluorescence data were acquired using a FACScan flow cytometer equipped with a 488-nm argon-ion laser and were analyzed using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, NJ). A minimum of 10,000 cells were acquired for each sample. A live gate was applied on forward and 90° side scatter to eliminate debris and dead cells from analysis. The percentage of PIM+ schizont-infected cells for each lymphocyte population was calculated by gating on the phenotypic marker of the particular population.

Phenotypes of in vivo-transformed cell lines.

A cow was infected with 0.5 ml of undiluted T. parva Chitongo CA0401 sporozoite stabilate, and from day 5 onwards, lymph node biopsy specimens were monitored daily for the presence of schizont-transformed cells. The first schizonts were detected on day 9, and blood was thus collected and PBMC purified. Purified PBMC were placed in 96-well culture plates at 5 × 105 cells per well and then incubated for 3 weeks. Lines were obtained from six wells of PBMC isolated at 18 days as well as 21 days postinfection (p.i.). The cells were then phenotyped by flow cytometry.

The experimental design and the use of animals were approved by the ILRI Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), and animals were treated in accordance with its guidelines.

Sequencing of T. parva Chitongo sporozoite p67.

The sequence of T. parva Chitongo p67 was derived after cloning of PCR products by use of the p67 primers IL-247 and IL-246, as previously described (26). Cloning was done following purification of the PCR products by use of a Wizard DNA clean-up kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). The purified product was then ligated into a plasmid vector (TA pCR2.1; Invitrogen). Competent cells were transformed and cultured, and glycerinated stabilates were sent to Eurogentec, Belgium, for sequencing using the dideoxy chain termination method on an ABI Prism analyzer (Perkin Elmer ABI) during a single run starting at both ends, for about 500 bp.

RESULTS

Infection of γδ T cells.

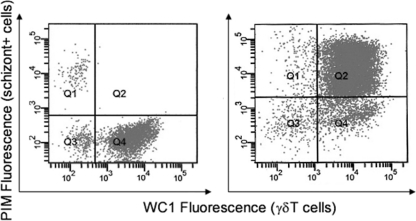

In a previous study (35), two Theileria strains with different degrees of virulence, T. parva Muguga and T. parva Chitongo, were able to infect PBMC. However, on two occasions, T. parva Chitongo but not T. parva Muguga sporozoites failed to infect some lymphocytes with a WC1+ phenotype from long-term cultures maintained with ConA and IL-2. To rule out the possibility that long-term culture had made the cell line resistant to T. parva Chitongo infection, we tested a sample of WC1+ γδ T cells prepared freshly from PBMC, as PBMC had been shown to become infected by T. parva Chitongo (35). CD4+ and γδ T cells were sorted by negative selection on MACS beads, and their phenotypes were confirmed by flow cytometry. The two cell populations were 95% pure but still contained some other cell types. Infected cells were tested daily for the presence of schizonts from day 2 p.i. to day 16 p.i., the period when transformed cells appear, as estimated in previous experiments (17). The T. parva Muguga sporozoites infected both the purified CD4+ (not shown) and γδ (Fig. 1) T cell subpopulations. The T. parva Chitongo sporozoites did not transform the purified CD4+ T cells (not shown), and most of the cells died by day 8 p.i. A few schizont-transformed cells were noted in the γδ T cells infected by T. parva Chitongo. However, upon two-color analysis of WC1 and PIM, infected cells were WC1− and thus appeared not to be γδ T cells (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Phenotype of schizont-positive cells 16 days after infection of WC1+ γδ T lymphocytes, enriched from PBMC by magnetic beads, with T. parva Chitongo (left) and T. parva Muguga (right). Infected cells were positive for the intracellular marker PIM. T. parva Muguga-infected cells were WC1+ cells (right; Q2), while T. parva Chitongo-infected cells (left; Q1) were not γδ T cells but were a contaminating cell type.

Sporozoite binding to host lymphocytes.

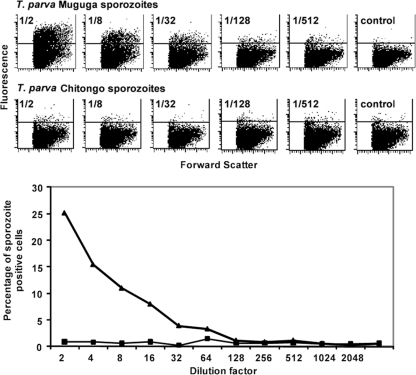

The observation that T. parva Chitongo sporozoites did not transform CD4+ αβ T cells or WC1+ γδ T cells or a cultured γδ T cell line could be the result of a lack of binding of sporozoites to the host cell surface or a failure of the parasite, once inside the cell, to mature into a macroschizont and transform the host cell. Therefore, a cytoadherence assay on PBMC was established to measure the former. Titration and binding of sporozoites to PBMC were carried out to measure the degree of sporozoite-host cell binding and the quantity of sporozoites needed. The anti-p67 MAb AR22.7 enabled the detection of the bound sporozoites. The T. parva Muguga and T. parva Chitongo stabilates were titrated in the range of 1/2 to 1/1,024. Over this dilution range, the fraction of PBMC that bound T. parva Muguga sporozoites diminished from 25% to 0% (Fig. 2). The negative control (no sporozoites) had a low background. However, no significant binding or only very-low-level binding was observed with T. parva Chitongo sporozoites (Fig. 2). To rule out the possibility that Chitongo sporozoites lacked the epitope recognized by MAb AR22.7, staining with another anti-p67 antibody (MAb AR23) was performed, but in this case also, no binding of Chitongo sporozoites could be observed.

Fig 2.

Binding of T. parva Muguga and T. parva Chitongo sporozoites to PBMC as a function of stabilate dilution. (Top) Dot plots representing sporozoite binding (fluorescence on the vertical axis), measured by flow cytometry using human MAb AR22.7. (Bottom) Percentages of sporozoite-positive cells as a function of dilution. Thick line with triangles, T. parva Muguga; thin line with squares, T. parva Chitongo. The control panels show fluorescence from PBMC that received no sporozoites.

As with PBMC, T. parva Chitongo sporozoites failed to bind the γδ T cell line (fewer than 1% fluorescent cells were detected), in contrast to T. parva Muguga sporozoites, which bound at least 30% of the γδ T cells (not shown). CD4+ and WC1+ T cells, purified by positive selection with magnetic beads, bound T. parva Muguga sporozoites but not T. parva Chitongo sporozoites.

In the last experiment, fresh PBMC were sorted into CD8α+ cells by negative selection using magnetic beads, with a purity of over 90% but with small contaminating populations of CD4+ (1.07%) and WC1+ (1.90%) cells (Fig. 3, top panel). This population was incubated with T. parva Muguga or T. parva Chitongo sporozoites (at stabilate dilutions of 8- and 2-fold, respectively, to guarantee equivalent sporozoite titers), and binding was monitored with anti-p67 MAb AR22.7 by flow cytometry. T. parva Muguga and T. parva Chitongo sporozoites bound specifically to 31.04% and 27.34% of purified CD8+ lymphocytes, respectively (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

The top panels show the purity of the enriched CD8+ PBMC before binding. The bottom panels show binding of sporozoites to the CD8+ population. T. parva Muguga (TpM) sporozoites (1/8 dilution) bound to 31.04% of purified CD8 T cells, as visualized by binding of anti-p67 MAb AR22.7 (leftmost dot plot). T. parva Chitongo (TpC) sporozoites (1/2 dilution) bound to 27.34% of CD8 T cells (3rd plot from left). The other figures are controls without the anti-p67 antibody (plots 2 and 4) or without sporozoites (plot 5).

Phenotypes of in vitro- and in vivo-transformed cell lines.

Theileria-transformed cell lines of each strain, obtained from in vitro infections of whole PBMC and cultured for at least 3 months, were phenotyped by flow cytometry (Table 1). A panel of 11 antibodies was used to phenotype the established cells. T. parva Chitongo lines were all CD3+ CD4− WC1− CD8+, and all expressed the CD8αβ heterodimer, suggesting that the original infected cells belonged to the CD8 subset. No other cell phenotypes were observed for T. parva Chitongo, in contrast to the T. parva Muguga-infected cell lines, which expressed markers for three T cell subpopulations (CD4+, WC1+, and CD8+ cells). The results further confirmed that all T. parva Chitongo-infected cell lines and only one T. parva Muguga-infected cell line expressed CD6 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Lymphocyte surface markers expressed on cultured Theileria parva-infected cell linesa

| Leukocyte antigen cell line | Phenotype |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD6 | CD2 | CD3 | CD4 | CD8α | CD8αβ | CD21 B cells | WC1 γδ T cells | γδ T cell receptor | Myeloid cells | |

| TpM 113 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − |

| TpM 163 | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − |

| TpM 164 | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| TpM 138 | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − |

| TpM 231 | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| TpM 104 | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| TpC CA0401 | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| TpC Zam2 A10 | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| TpC Zam2 A9 | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| TpC Zam2 H10 | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| TpC Zam2 B4 | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

The antibodies used were as follows: IL-A27, IL-A44, MM1A, IL-A12, IL-A105, CC58, IL-A65, CC15, GB21A, and IL-A24, in order according to the columns (left to right) of the table.

Twelve in vivo T. parva Chitongo-infected cell lines were obtained from 12 independent cultures of PBMC taken from an infected cow. All 12 lines were positive for CD8 and negative for CD4.

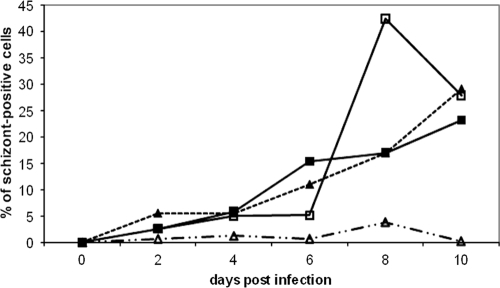

Infection of CD8+ T lymphocytes.

We next compared the progress of transformation of CD8 T cells after infection by T. parva Chitongo and T. parva Muguga sporozoites. Purified CD4 and CD8 T cells were infected by both isolates, and the percentage of schizont-positive cells was monitored by counting Giemsa-stained cells under a microscope (Fig. 4). We used a 2-fold dilution for the T. parva Muguga stabilate and an 8-fold dilution for the T. parva Chitongo stabilate so we would compare identical sporozoite titers (35). The data confirmed that T. parva Muguga infected both T lymphocyte subpopulations and that T. parva Chitongo infected only CD8+ T cells. Transformed CD8 cells appeared with the same kinetics for both isolates.

Fig 4.

Percentages of schizont-positive cells as a function of time in culture. Data are shown for T. parva Chitongo-infected purified CD4+ (broken lines, open triangles) and CD8+ (broken lines, closed triangles) cells and T. parva Muguga-infected purified CD4+ (full lines, open boxes) and CD8+ (full lines, closed boxes) cells. Very few schizonts appeared in the CD4 cells infected by T. parva Chitongo compared to T. parva Muguga-infected CD4+ cells. The time of appearance of transformed cells and the growth rate were very similar for T. parva Muguga- and T. parva Chitongo-infected CD8+ cells.

Sequencing of T. parva Chitongo sporozoite p67.

The p67 sequence from T. parva Chitongo was aligned with the T. parva Muguga sequence (GenBank accession no. U40703), and no differences were found between the 2 alignments over the 2.2-kbp amplified region.

DISCUSSION

In our previous study (35), we demonstrated that T. parva Chitongo was less virulent than T. parva Muguga. The present study aimed to evaluate the possible mechanism of this difference in virulence. We compared the infectivities of T. parva Muguga and T. parva Chitongo for different subpopulations of bovine lymphocytes. The data confirmed previous studies (3, 15) showing that in a bulk infection of whole PBMC, T. parva Muguga sporozoites infected CD4+ T cells preferentially, but not exclusively, and could also infect any purified lymphocyte population. In contrast, the results described in this paper showed that only CD8+ T cells could be infected and transformed by T. parva Chitongo sporozoites. This was confirmed by examining the phenotypes of other transformed cell lines: T. parva Chitongo-transformed lines were exclusively CD8+ CD4−, sometimes with low levels of acquired WC1, while the phenotypes of the T. parva Muguga-transformed lines were a lot more mixed but were mostly CD4+. This was also the case for in vivo-transformed cells: 12 cell lines recovered from an in vivo T. parva Chitongo-infected animal were exclusively CD8+ CD4−, suggesting that CD4 T cells are not infected and transformed during natural infection. The specificity of T. parva Chitongo for CD8+ T cells appeared to occur during the initial binding step, as adherence was observed only with purified CD8+ PBMC, not with CD4+ T cells or WC1+ γδ T cells. The CD8 restriction of T. parva Chitongo was observed with cells from Bos taurus and B. taurus × Bos indicus crossbred cattle. Such restricted affinity of a Theileria isolate for a specific T cell subpopulation has never been observed before. This may account for the lower virulence of T. parva Chitongo, as reported from field observations (9) and confirmed by in vivo and in vitro infections (35). Several mechanisms, which are not necessarily exclusive, might explain this reduced virulence. First of all, the initial number of target cells could influence the onset of parasitosis and pathology. T. parva Chitongo targets the CD8+ cell population, which makes up about 10% of PBMC, while the T. parva Muguga target population encompasses all T and B lymphocytes, making up about 80 to 90% of PBMC. This means that in vivo, sporozoites of T. parva Muguga will be able to infect more target cells in a shorter time than those of T. parva Chitongo. The quantitative difference may be crucial, as this initial large number of infected cells may allow T. parva Muguga to outcompete the immune response: the immune response has to reach protective levels before parasite numbers become lethal. There is also a qualitative difference, since different cell types might enhance pathology in different ways, e.g., through secretion of particular cytokines or expression of certain adhesion molecules on the surface.

When similar host cell phenotypes (CD8+) were infected with the two isolates, their growth kinetics were similar (Fig. 4), suggesting that the rates of transformation and cell division were the same for both isolates. This supports the hypothesis forwarded in our previous study that the presence of fewer target cells in the original PBMC population resulted in a longer lag phase and in a delay of the onset of logarithmic growth. But conditions in vivo are different: in vitro, the number of CD8 target cells is limiting, and not all sporozoites may find a suitable target cell, while in vivo, given enough time and without elimination by innate responses such as those of macrophages, sporozoites will eventually encounter a CD8+ cell, and theoretically, each sporozoite can find a target. Thus, we expected that the delay of T. parva Chitongo compared to T. parva Muguga for development of transformed cells would be much shorter in vivo than the in vitro situation, which is exactly what was observed (35).

The failure of T. parva Chitongo sporozoites to bind CD4+ and γδ T cells suggests that the ligand-receptor molecules that mediate the specificity of cytoadherence must be different from those for T. parva Muguga. If p67 were the only adhesion molecule on the sporozoite, we would expect similar binding profiles for the two T. parva isolates, since the p67 sequences are 100% conserved. These data led us to postulate the existence of a second adhesion molecule on the sporozoite. It might even be the case that the p67 surface molecule has no direct role in adhesion at all. In that case, the capacity of anti-p67 antibodies to block binding could be explained by steric hindrance, an argument that was also used to explain how one antibody to CD45 on the host cell could block sporozoite binding yet removal of CD45 by protease treatment did not reduce the efficiency of binding (34). Antibodies against the Theileria antigen PIM, a schizont molecule that is expressed only weakly in sporozoites, also possess neutralizing capacity (36). Only one study has shown some evidence for a role of p67 in adhesion (30), as recombinant p67 bound lymphocytes with a very weak affinity.

One possible concern often raised in comparing T. parva Muguga with other isolates is that frequent passaging of T. parva Muguga through ticks and cattle might have selected for different traits, in this case, T. parva Muguga genotypes that attack a broader target cell population. However, other virulent Theileria stocks, including T. parva Marikebuni and T. parva Mariakani, were also shown to infect different cell types at a time when they had undergone few passages (5, 20). This also underscores the fact that the binding pattern of T. parva Chitongo is distinct from that of the other isolates examined. Finally, selection by culturing of infected lymphocytes could not have affected the virulence traits, as both parasites used in the study have never gone through a culture stage.

The benefit of restricted cell tropism for T. parva Chitongo is likely to be the associated low virulence. In areas where parasite transmission is not frequent, such as areas where ticks have a unimodal distribution (4), low-virulence strains will have a selective advantage, as they may keep the host alive and prolong the carrier status, thereby maximizing chances for transmission. While reduced cell tropism may contribute to low virulence, it may not be the only cause, and the impact of the different posttransformation stages on pathology should be investigated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Anke Van Hul of the Animal Health Unit at ITM for help in maintenance of cell cultures and John Wasilwa at ILRI and Francoise Dumortier of the Laboratory of Molecular Cell Biology of KU Leuven for technical help with flow cytometry. We thank Evans Taracha for help with establishing the collaborative effort between ILRI and ITM.

This work was funded by the Directorate General for Development Co-Operation, Belgium, through an ITM alumnus fellowship. Dirk A. E. Dobbelaere was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 3100A0-116653).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 December 2011

This article is ILRI paper number IL-200941.

REFERENCES

- 1. Akoolo L, et al. 2008. Evaluation of the recognition of Theileria parva vaccine candidate antigens by cytotoxic T lymphocytes from Zebu cattle. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 121:216–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baldwin CL, Malu MN, Kinuthia SW, Conrad PA, Grootenhuis JG. 1986. Comparative analysis of infection and transformation of lymphocytes from African buffalo and Boran cattle with Theileria parva subsp. parva and T. parva subsp. lawrencei. Infect. Immun. 53:186–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baldwin CL, et al. 1988. Bovine T-cells, B-cells and null cells are transformed by protozoan parasite Theileria parva. Infect. Immun. 56:462–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Billiouw M, et al. 2002. Theileria parva epidemics: a case study in eastern Zambia. Vet. Parasitol. 107:51–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Conrad PA, et al. 1989. Infection of bovine T-cell clones with genotypically distinct Theileria parva parasites and analysis of their cell surface phenotype. Parasitology 99:205–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dobbelaere DA, Spooner PR, Barry WC, Irvin AD. 1984. Monoclonal antibody neutralizes the sporozoite stage of different Theileria parva stocks. Parasite Immunol. 6:361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Emery DL, MacHugh ND, Morrison WI. 1988. Theileria parva (Muguga) infects bovine T-lymphocytes in vivo and induces coexpression of BoT4 and BoT8. Parasite Immunol. 10:379–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reference deleted.

- 9. Geysen D, Bishop R, Skilton R, Dolan TT, Morzaria S. 1999. Molecular epidemiology of Theileria parva in the field. Trop. Med. Int. Health 4:A21–A27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goddeeris BM, Morrison WI. 1988. Techniques for the generation, cloning and characterization of bovine cytotoxic T cells specific for the protozoan Theileria parva. J. Tissue Cult. Methods 11:101–110 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Graham SP, et al. 2001. Proinflammatory cytokine expression by Theileria annulata infected cell lines correlates with the pathology they cause in vivo. Vaccine 19:2932–2944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reference deleted.

- 13. Reference deleted.

- 14. Knight P, et al. 1996. Conservation of neutralizing determinants between the sporozoite surface antigens of Theileria annulata and Theileria parva. Exp. Parasitol. 82:229–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lalor PA, Morrison WI, Black SJ. 1986. Monoclonal antibodies to bovine leukocytes define heterogenicity of target cells for in vitro parasitosis by Theileria parva, p 72–87 In Morrison WI. (ed), The ruminant immune system in health and disease. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 16. MacHugh ND, Sopp P. 1991. Individual antigens of cattle. Bovine CD8 (BoCD8). Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 27:65–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marcotty T, et al. 2002. Immunisation against Theileria parva in eastern Zambia: influence of maternal antibodies and demonstration of the carrier status. Vet. Parasitol. 2450:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reference deleted.

- 19. Morrison WI, MacHugh ND, Lalor PA. 1996. Pathogenicity of Theileria parva is influenced by the host cell type infected by the parasite. Infect. Immun. 64:557–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morzaria SP, Dolan TT, Norval RA, Bishop RP, Spooner PR. 1995. Generation and characterization of cloned Theileria parva parasites. Parasitology 111:39–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Musoke A, Morzaria S, Nkonge C, Jones E, Nene V.1992. A recombinant sporozoite surface antigen of Theileria parva induces protection in cattle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:514–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Musoke AJ, Nene V, McKeever D. 1995. Epitope specificity of bovine immune responses to the major surface antigen of Theileria parva sporozoites, p 57–61 In Chanock RM, Brown F, Ginsberg HS, Norrby E. (ed), Vaccines 95. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 23. Naessens J, Howard CJ, Hopkins J. 1997. Nomenclature and characterisation of leukocyte differentiation antigens in ruminants. Immunol. Today 18:365–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Naessens J, et al. 1985. De novo expression of T cell markers on Theileria parva-transformed lymphoblasts in cattle. J. Immunol. 135:4183–4188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Naessens J, Nthale JM, Muiya P. 1996. Biochemical analysis of preliminary clusters in the non-lineage panel. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 52:347–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nene V, Musoke A, Gobright E, Morzaria S. 1996. Conservation of the sporozoite p67 vaccine antigen in cattle-derived Theileria parva stocks with different cross-immunity profiles. Infect. Immun. 64:2056–2061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nene V, Gobright E, Bishop R, Morzaria S, Musoke A. 1999. Linear peptide specificity of bovine antibody responses to p67 of Theileria parva and sequence diversity of sporozoite-neutralizing epitopes: implications for a vaccine. Infect. Immun. 67:1261–1266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rocchi MS, Ballingall KT, MacHugh ND, McKeever DJ. 2006. The kinetics of Theileria parva infection and lymphocyte transformation in vitro. Int. J. Parasitol. 36:771–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reference deleted.

- 30. Shaw MK, Tilney LG, Musoke AJ, Teale AJ. 1995. MHC class I molecules are an essential cell surface component involved in Theileria parva sporozoite binding to bovine lymphocytes. J. Cell Sci. 108:1587–1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reference deleted.

- 32. Shiels B, et al. 2006. Alteration of host cell phenotype by Theileria annulata and Theileria parva: mining for manipulators in the parasite genomes. Int. J. Parasitol. 36:9–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Simonian PL, et al. 2006. Regulatory role of T cells in the recruitment of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to lung and subsequent pulmonary fibrosis. J. Immunol. 177:4436–4443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Syfrig J, Wells C, Daubenberger C, Musoke AJ, Naessens J. 1998. Proteolytic cleavage of surface proteins enhances susceptibility of lymphocytes to invasion by Theileria parva sporozoites: evidence for involvement of a parasite protease. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 76:125–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tindih HS, Marcotty T, Naessens J, Goddeeris BM, Geysen D. 2009. Demonstration of differences in virulence between two Theileria parva isolates. Vet. Parasitol. 168:223–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Toye P, Gobright E, Nyanjui J, Nene V, Bishop R. 1995. Structure and sequence variation of the genes encoding the polymorphic, immunodominant molecule (PIM), an antigen of Theileria parva recognized by inhibitory monoclonal antibodies. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 73:165–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reference deleted.