Abstract

Host defense peptides are innate immune effectors that possess both bactericidal activities and immunomodulatory functions. Deficiency in the human host defense peptide LL-37 has previously been correlated with severe periodontal disease. Treponema denticola is an oral anaerobic spirochete closely associated with the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. The T. denticola major surface protein (MSP), involved in adhesion and cytotoxicity, and the dentilisin serine protease are key virulence factors of this organism. In this study, we examined the interactions between LL-37 and T. denticola. The three T. denticola strains tested were susceptible to LL-37. Dentilisin was found to inactivate LL-37 by cleaving it at the Lys, Phe, Gln, and Val residues. However, dentilisin deletion did not increase the susceptibility of T. denticola to LL-37. Furthermore, dentilisin activity was found to be inhibited by human saliva. In contrast, a deficiency of the T. denticola MSP increased resistance to LL-37. The MSP-deficient mutant bound less fluorescently labeled LL-37 than the wild-type strain. MSP demonstrated specific, dose-dependent LL-37 binding. In conclusion, though capable of LL-37 inactivation, dentilisin does not protect T. denticola from LL-37. Rather, the rapid, MSP-mediated binding of LL-37 to the treponemal outer sheath precedes cleavage by dentilisin. Moreover, in vivo, saliva inhibits dentilisin, thus preventing LL-37 restriction and ensuring its bactericidal and immunoregulatory activities.

INTRODUCTION

Host defense peptides (HDPs) are cationic and amphipathic molecules produced mainly on epithelial surfaces and by phagocytic cells (18). HDPs are inducible by injury or microbial burden and protect the host by killing pathogens directly and by acting as multifunctional effectors that elicit cellular processes to promote anti-infective and repair responses (4). Direct killing of pathogens by host defense peptides is a major protective mechanism for generating an antimicrobial barrier that protects against systemic and skin pathogens (11, 12, 55) and lung infections (3) and for balancing the microflora in the oral cavity (32, 61, 79). The oral HDPs include α- and β-defensins, histatins, and the cathelicidin LL-37 (16, 29). Their importance has been shown in Kostmann syndrome, in which patients deficient in LL-37 and the α-defensin HNP-1 develop severe periodontal disease promoted by the LL-37-sensitive organism Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (61). Periodontal diseases are polybacterially induced (70), multifactorial (80) inflammatory processes of the tooth attachment apparatus (67) and are the primary cause of tooth loss after the age of 35 (45).

Proteolysis is a common strategy for microbial escape from HDPs. Treponema denticola, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Tannerella forsythia are strongly associated with periodontal diseases (70). These microorganisms, characterized by their high proteolytic and peptidolytic capacities (35, 42, 47), can hydrolyze the oral HDPs and inactivate their antimicrobial activity (17, 42, 60). Nevertheless, these bacteria show different susceptibilities to oral HDPs. While T. forsythia is susceptible to β-defensins (38) and P. gingivalis shows selective strain susceptibility to these peptides (38, 39), oral treponemes seem to be relatively resistant to human β-defensins through a combination of decreased defensin binding and effective efflux (6, 7).

Proteases from both P. gingivalis and T. forsythia degrade LL-37 in vitro (1, 42). Nevertheless, T. forsythia is susceptible to LL-37 (42), and the resistance of P. gingivalis to direct killing by LL-37 is protease independent and at least partially due to the low affinity of the peptide for this bacteria (1).

LL-37 is poorly active against the systemic pathogenic spirochetes Leptospira interrogans, Borrelia burgdorferi, and Treponema pallidum, with minimum bactericidal concentration values ranging from 150 to 450 μg/ml (33 to 100 μM) (66). Thus, it seemed of interest to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of LL-37 against periodontopathogenic spirochetes.

The periodontopathogenic spirochete T. denticola (70) possesses a number of virulence factors. These include motility, the ability to attach to host tissues (21), coaggregation with other oral bacteria (41, 62), complement evasion mechanisms (53), and the presence of several outer sheath and periplasmic proteolytic and peptidolytic activities (47, 63, 64). The proteolytic capacity of T. denticola sustains its nutritional requirements (69) and ATP production (65, 68). Two components associated with the spirochetes' outer sheaths and extracellular vesicles are the major surface protein (also known as the major outer sheath protein [MSP]) and a serine protease, dentilisin, previously known as the chymotrypsin-like protease (74). Recent bioinformatics analysis reclassified dentilisin as a member of the subtilisin rather than the chymotrypsin family (13, 37). Dentilisin is involved in the degradation of membrane basement proteins (laminin, fibronectin, and collagen IV) (64), serum proteins (fibrinogen, transferrin, IgG, and IgA), including protease inhibitors (α1-antitrypsin, antichymotrypsin, antithrombin, and antiplasmin) (30, 74), and bioactive peptides (50). Degradation of tight junction proteins by dentilisin seems to enable the penetration of epithelial cell layers by this oral spirochete (10).

MSP is a major antigen (9, 28) with pore-forming activity (20). This abundant membrane protein mediates the binding of T. denticola to fibronectin, fibrinogen, laminin, and collagen (19, 25), induces macrophage tolerance to further activation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (56), and elicits cytotoxic effects in different cell types (24, 75).

The objectives of this study were to examine the effectiveness of LL-37 against T. denticola and to study the interactions between the two oral components. We found that in contrast to its poor activity against systemic spirochetes, LL-37 possesses effective bactericidal activity against T. denticola. This activity was targeted and enhanced by the presence of the treponeme's major outer sheath protein and preceded degradation by the treponeme's dentilisin protease. Surprisingly, saliva was found to inhibit dentilisin, attenuating its virulence properties and conserving LL-37 activity despite the presence of the protease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

LL-37 peptide.

LL-37 (LLGDFFRKSKEKIGKEFKRIVQRIKDFLRNLVPRTES) was synthesized as described previously by the solid-phase method on a fully automated, programmable peptide synthesizer (2). Peptide integrity and purity (greater than 95%) were determined by analytical high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry (MS).

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

T. denticola strains ATCC 35404 (TD4), ATCC 33520, and GM-1, and T. denticola mutants K1 (lacking the outer sheath dentilisin protease) (36) and MHE (lacking the major outer sheath protein [MSP]) (26), were grown in GM-1 medium (5) in a Bactron anaerobic (85% N2, 10% H2, and 5% CO2) environmental chamber (Sheldon Manufacturing Inc., Cornelius, OR) at 37°C. Late-exponential-phase cultures, corresponding to an optical density at 660 nm (OD660) of 0.250 to 0.300, were obtained following incubation for 4 days. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth under aerobic conditions. Bacterial purity was determined by phase microscopy and Gram staining.

Growth inhibition by LL-37.

Following 4 days of bacterial growth, the susceptibility of T. denticola to LL-37 was evaluated spectrophotometrically at 660 nm with or without increasing concentrations of LL-37. The optical density at time zero was considered 100% growth inhibition. The optical density of bacterial growth in the absence of LL-37 was considered 0% growth inhibition.

The inhibition of T. denticola TD4 growth following 1 h of exposure to LL-37 was determined as follows. T. denticola cells (1.0 × 108/ml) from 4-day-old cultures were incubated in GM-1 culture medium with or without LL-37 (50 μg/ml) for 1 h. Bacteria were diluted 20× in GM-1 medium and were grown for 36 h. The optical density at time zero (after dilution) was considered 100% growth inhibition. The optical density of bacterial growth in the absence of LL-37 was considered 0% growth inhibition. The results presented are means and standard deviations (SD) for two independent experiments performed in quadruplicate.

Bacterial viability.

Bacterial killing by LL-37 was evaluated by measuring intracellular ATP levels, an energetic parameter commonly used as an indicator of cell injury and viability (71). Briefly, T. denticola cells (1.0 × 108/ml) from 4-day-old cultures were incubated in GM-1 culture medium with or without LL-37 for the time stated (see Fig. 2 and 7). The cells were then centrifuged (10,000 × g, 5 min), resuspended in 1 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and transferred to a 2-ml microcentrifuge tube containing glass beads (diameter, 160 μm; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The cells were disrupted with the aid of a Fast Prep cell disrupter (Bio 101, Savant Instruments, Inc., Holbrook, NY). ATP levels were determined using the ATP Bioluminescence assay kit (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany). ATP levels of bacteria not treated with LL-37 were considered to represent 0% killing, and ATP levels of heat-killed bacteria (exposure to 100°C for 5 min) were defined as 100% killing.

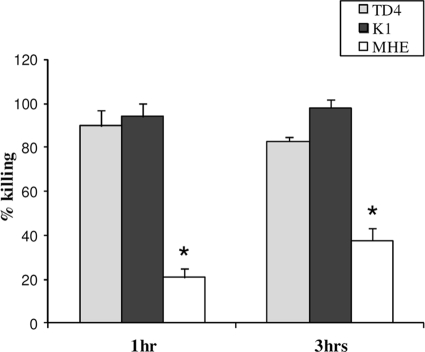

Fig 2.

Effects of exposure time, dentilisin protease, and the major outer sheath protein on the susceptibility of T. denticola to LL-37. T. denticola TD4 and T. denticola mutants K1 (lacking the outer sheath protease dentilisin) and MHE (lacking the major outer sheath protein) were incubated with 50 μg/ml LL-37 for the indicated times and were analyzed for intracellular ATP levels. The data are means and standard deviations for three independent experiments performed in duplicate. *, P < 0.0001 compared with T. denticola TD4 and T. denticola K1.

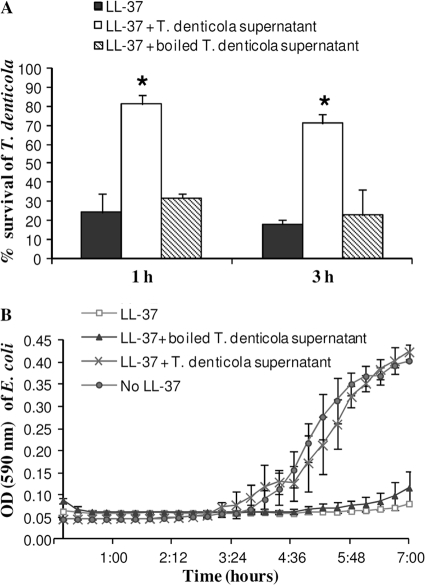

Fig 7.

Inactivation of LL-37 by T. denticola supernatant. LL-37 incubated for 2 h without or with T. denticola supernatant or with heat-inactivated supernatant (boiled) was added to a growing culture of T. denticola TD4 (50 μg/ml) (A) or E. coli (20 μg/ml) (B). (A) Intracellular ATP was measured to calculate the percentage of treponeme survival. ATP levels of bacteria not treated with LL-37 were considered to represent 100% survival, and ATP levels of heat-killed bacteria (exposure to 100°C for 5 min) were defined as 0% survival. Data are means and standard deviations for three independent experiments performed in duplicate. *, P < 0.0001 compared with LL-37 incubated without T. denticola supernatant or with heat-inactivated (boiled) supernatant. (B) Incubations with untreated LL-37 and with no LL-37 were used as controls. The data are means and standard deviations for a representative experiment performed in duplicate and repeated 3 times.

Purification of dentilisin.

The protease was purified from isolated T. denticola outer sheaths or extracellular vesicles, followed by preparative sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and electroelution as described previously (64). The specific activity of the purified dentilisin was on the order of 100 to 150 U/mg, a 100-fold purification from that of total treponemal cells (1.2 U/mg).

Protease assays.

Dentilisin activity was determined by cleavage of the chromogenic substrate succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-p-nitroanilide (SAAPNA) (64). Trypsin-like activity was determined with the chromogenic substrate Nα benzoyl-l-Arg-p-nitroanilide (BAAPNA), as described previously (48).

Enzymatic degradation of LL-37.

Four-day-old T. denticola cultures were centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 × g in a microcentrifuge (Eppendorf, Germany), and the supernatant was collected. LL-37 (10 μg) was incubated with 10 μl of T. denticola supernatant (0.15 to 0.2 U/ml of SAAPNA-degrading activity) or with 10 ng purified dentilisin in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) for 2 h at 37°C. The reaction was terminated by the addition of SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiling for 3 min at 100°C. The samples were centrifuged at 10,000 × g in a microcentrifuge for 2 min and were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE. The gels were stained with Coomassie blue. The effects of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (1 mM), chymostatin (0.4 mM), and saliva (13 μl of saliva cleared by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 10 min; 2 × 10−3 U SAAPNA-degrading activity) on the enzymatic degradation of LL-37 were evaluated by incubating the supernatant with the inhibitors for 20 min at room temperature prior to addition of the peptide.

MS.

LL-37 was incubated with purified dentilisin as described above. The hydrolyzed peptide mixture was solid-phase extracted with a C18 resin-filled tip (ZipTip; Millipore, Billerica, MA) and was nanosprayed into the Orbitrap MS system in a 50% CH3CN–1% CHOOH solution.

Mass spectrometry was carried out with an Orbitrap system (Thermo Finnigan) using a nanospray attachment (76). Data were analyzed using the BioWorks package, version 3.3.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.

LL-37 was labeled with Alexa Fluor 350 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) as described previously (1). T. denticola was grown to late-logarithmic phase, sedimented for 3 min at 10,000 × g, and brought to an OD600 of 1 in PBS. Two hundred microliters of cells was incubated with 20 μl of labeled peptide for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were washed in 0.3 ml PBS and were resuspended in 0.3 ml PBS. Samples were subjected to flow cytometry using the LSR II instrument (BD Biosciences) and were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). Runs were repeated in three independent experiments with similar results.

LL-37 binding assay.

The MSP complex was isolated and was highly enriched by sequential detergent extraction and autoproteolysis of T. denticola extracts as described previously (52). MSP (1 μl; 1, 0.1, or 0.01 μg/ml), fibrinogen, or bovine serum albumin (BSA) was attached to a nitrocellulose membrane at room temperature, blocked with 5% skim milk in PBS for 1 h, and incubated with LL-37 (1 μg/ml in PBS) for 1 h. After three washes with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, LL-37 binding was detected with anti-LL37 rabbit serum as described previously (33).

Effect of proteolysis by T. denticola supernatant on the antimicrobial activity of LL-37.

LL-37 was treated for 2 h with T. denticola supernatant or with heat-inactivated supernatant (negative control) as described above. The remaining antimicrobial activity of the truncated LL-37 was tested on T. denticola and on E. coli as follows. Treated LL-37 was added to a growing culture of T. denticola TD4 (50 μg/ml), and the percentage of treponemal killing was determined by measuring intracellular ATP levels as described above. ATP levels of bacteria not treated with LL-37 were considered to represent 0% killing, and ATP levels of heat-killed bacteria (exposure to 100°C for 5 min) were defined as 100% killing. For the inhibition of E. coli growth, treated or untreated LL-37 (4 μg) was brought to a total volume of 50 μl with PBS and was added to 150 μl of E. coli ATCC 25922 (overnight culture, diluted 1:5,000 in BHI). The growth of E. coli was measured continually in 96-well plates (Nunc, Denmark) at 37°C, and absorbance was followed as the OD595 (GENios reader; Tecan Austria).

Statistical analysis.

Data are reported as means ± SD. Statistical tests were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Student t test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Antibacterial activity of LL-37 against T. denticola.

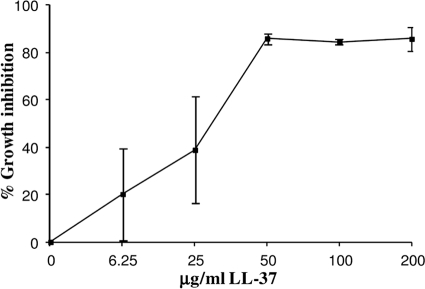

Inhibition of the growth of T. denticola by LL-37 was tested at LL-37 concentrations reaching 200 μg/ml. As shown in Fig. 1, an LL-37 concentration of 50 μg/ml (11 μM) or higher inhibited the growth of T. denticola ATCC 35404 (TD4) by 85%. Higher peptide concentrations did not increase growth inhibition (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Inhibition of T. denticola growth by LL-37. T. denticola TD4 (ATCC 35404) (1 × 108 cells/ml) was inoculated in GM-1 medium under anaerobic conditions at 37°C with or without increasing concentrations of LL-37. Bacterial growth was measured spectrophotometrically at 660 nm after 4 days. The optical density at time zero was considered 100% growth inhibition. The optical density of bacterial growth in the absence of LL-37 was considered 0% growth inhibition. The data are means and standard deviations for a representative experiment performed in triplicate and repeated twice.

To determine whether susceptibility to LL-37 is common among T. denticola strains, growth inhibition by LL-37 (50 μg/ml) was also tested with T. denticola ATCC 33520 and GM-1. No significant differences in susceptibility to LL-37 were observed among the three T. denticola strains tested (data not shown).

Next, the kinetics of T. denticola killing by the antimicrobial peptide was evaluated by measuring ATP levels in T. denticola cells exposed to LL-37. The time-dependent killing of T. denticola TD4 is shown in Fig. 2. Incubation of T. denticola with LL-37 (50 μg/ml) consistently produced a sharp decay (89.7% ± 7%) in intracellular ATP levels after 1 h. This ATP decay corresponded with a 92.8% ± 2% reduction in bacterial growth 36 h after peptide dilution (data not shown). No further significant decay in intracellular ATP levels was observed after a 3-h or overnight (data not shown) incubation with the peptide. These data suggest that most of the T. denticola killing by LL-37 occurs within 1 h of cell exposure.

Effects of dentilisin and the major outer sheath protein on the susceptibility of T. denticola to LL-37.

In order to gain insight into factors that affect the susceptibility of T. denticola to LL-37, we compared the effects of LL-37 on two T. denticola mutants: K1 (lacking the outer sheath dentilisin protease) (36) and MHE (lacking MSP) (26). After exposure to LL-37, the killing (as determined by a decrease in intracellular ATP levels) of the K1 mutant was not significantly different from that of wild-type TD4. In contrast, the MHE mutant demonstrated significantly higher resistance (P < 0.0001) to LL-37 than did TD4 and K1, both after 1 h and after 3 h of incubation with the antimicrobial peptide (Fig. 2).

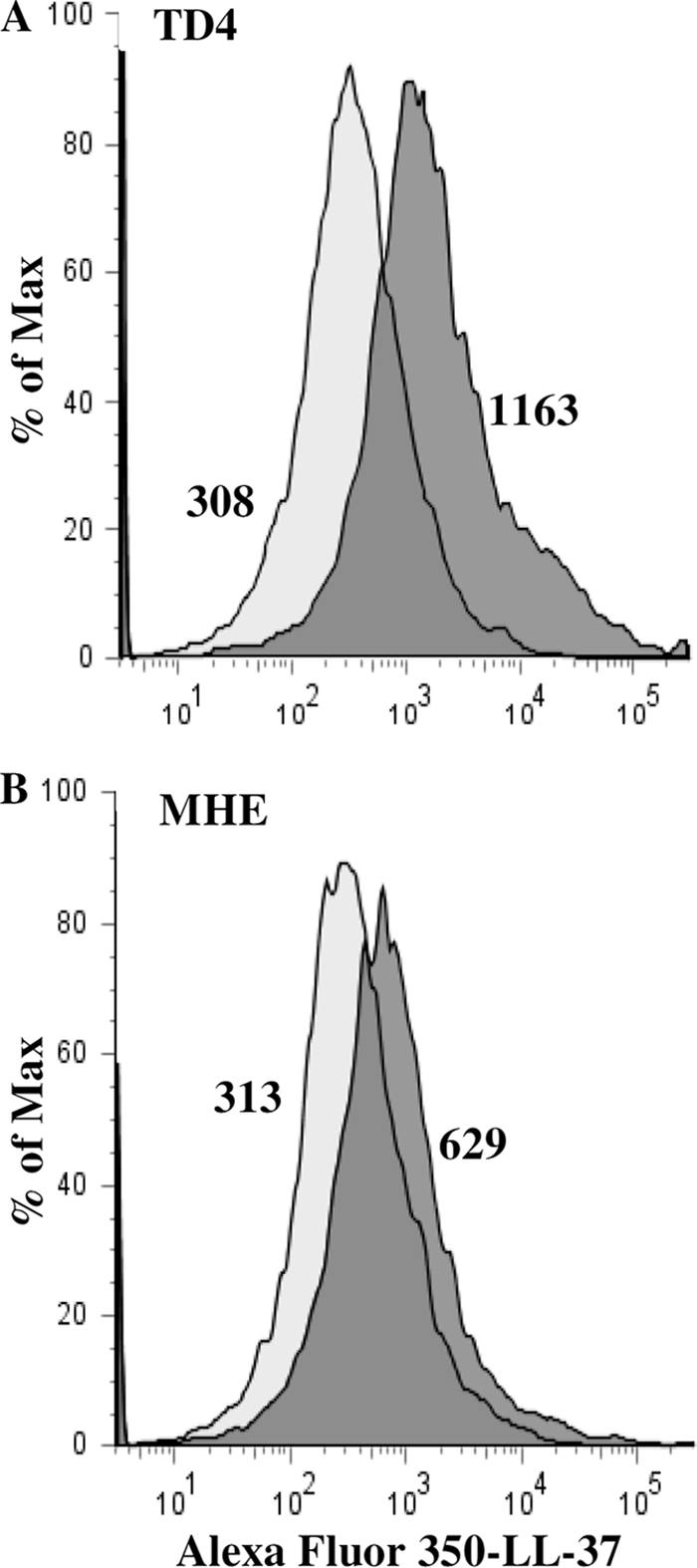

The binding of LL-37 to T. denticola is facilitated by the major outer sheath protein.

The mechanism of decreased susceptibility to LL-37 in the MHE mutant was further investigated. The binding of LL-37 to T. denticola TD4 was compared with its binding to the T. denticola MHE mutant by using flow cytometry. As can be seen in Fig. 3, fluorescently labeled LL-37 bound better (approximately 2-fold more) to the wild-type TD4 strain than to the major outer sheath protein-deficient T. denticola MHE mutant.

Fig 3.

The binding of Alexa Fluor 350-labeled LL-37 to T. denticola is enhanced by the major outer sheath protein. Wild-type TD4 (A) and MHE mutant (lacking the major outer sheath protein) (B) cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 350-labeled LL-37 and were analyzed by flow cytometry. Light shaded histograms, unlabeled bacteria; dark shaded histograms, bacteria reacted with Alexa Fluor 350-labeled LL-37. The geometric mean number for each histogram is given. The results shown are representative of three separate experiments.

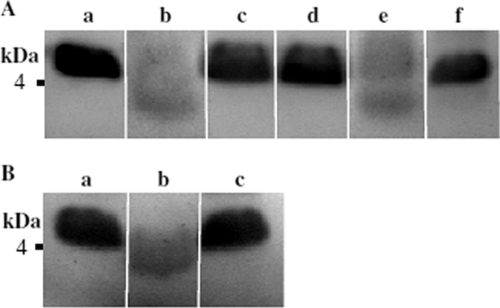

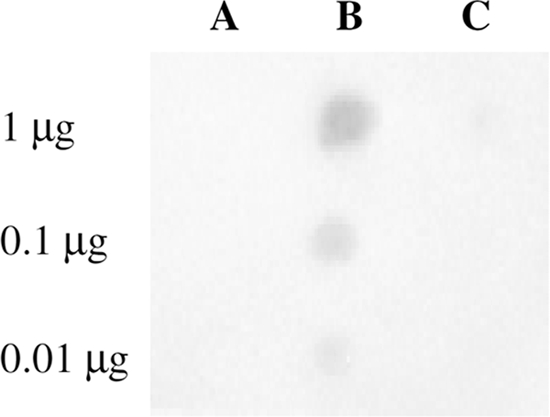

The decreased binding of LL-37 to T. denticola in the absence of the major outer sheath protein led us to investigate the role of MSP in the attachment of LL-37 to T. denticola. MSP, fibrinogen, and bovine serum albumin were attached to nitrocellulose membranes and were incubated with LL-37. The binding of LL-37 to the proteins was immunodetected using rabbit anti-LL-37 antibodies (33). As shown in Fig. 4, LL-37 bound strongly to MSP at all concentrations tested. Weak binding to fibrinogen could be detected only at its highest concentration, while BSA did not bind LL-37. These data suggest that MSP may contribute to the initial attachment of LL-37 to the treponemal surface.

Fig 4.

LL-37 binds MSP. Bovine serum albumin (A), MSP (B), and fibrinogen (C), in the amounts indicated, were bound to nitrocellulose membranes and were reacted with LL-37 (1 μg/ml). Bound LL-37 was detected using anti-LL-37 rabbit serum as described in Materials and Methods.

LL-37 degradation by T. denticola.

T. denticola contains peptidolytic and proteolytic activities (47) with substrate specificities that could potentially hydrolyze LL-37. Dentilisin proteolytic activity is found in the outer sheath and in extracellular vesicles of the treponeme (64), while the trypsin-like and proline endopeptidase peptidolytic activities are functional as components of intact cells (48, 49) and are not found in the extracellular supernatant. In order to test the ability of T. denticola to degrade LL-37, 4-day-old culture supernatants, expressing dentilisin activity (0.15 to 0.2 U/ml) and no detectible trypsin-like activity, were tested for hydrolysis of LL-37. T. denticola TD4 supernatant cleaved LL-37 to a lower-molecular-weight (lower-MW) peptide (Fig. 5Ab). The degradation of LL-37 by TD4 supernatants was inhibited completely by phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (1 mM) (Fig. 5Ad) and partially by chymostatin (0.4 mM) (Fig. 5Ae), both inhibitors of dentilisin (64). Neither supernatants (Fig. 5Ac) nor isolated outer sheaths (data not shown) prepared from the K1 mutant deficient in dentilisin activity cleaved the antimicrobial peptide. Purified dentilisin cleaved LL-37 to a low-molecular-weight LL-37 derivative with an electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 5Bb) similar to that of the derivative obtained by hydrolysis with TD4 supernatants (Fig. 5Ab), suggesting that dentilisin could potentially protect the treponemal cells from the lethal effect of LL-37.

Fig 5.

LL-37 degradation by the T. denticola dentilisin. (A) LL-37 (10 μg) was incubated for 2 h at 37°C without (a) or with T. denticola TD4 (wild-type) supernatant (b), T. denticola K1 (dentilisin activity-deficient) supernatant (c), or T. denticola TD4 supernatant preincubated (20 min) with either 1 mM PMSF (d), 0.4 mM chymostatin (e), or saliva (13 μl cleared saliva/10 μl supernatant) (f). (B) LL-37 was incubated as described above without (a) or with purified dentilisin in the absence (b) or presence (c) of saliva (13 μl cleared saliva/2 × 10−3 U purified dentilisin).

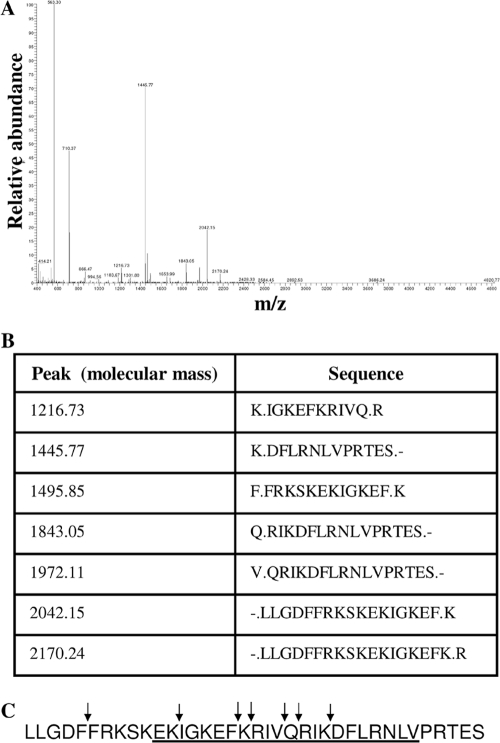

The products of LL-37 dentilisin digestion were submitted to electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS (Fig. 6A), and the peaks were identified by tandem MS (MS-MS) (Fig. 6B). Phe, Lys, Gln, and Val residues at the P1 position were found to be cleaved by dentilisin.

Fig 6.

LL-37 sites cleaved by dentilisin. (A) ESI-MS of LL-37-derived peptides. (B) MS-MS identification of the peaks generated by hydrolysis with purified dentilisin. (C) Intact LL-37 sequence. Arrows indicate the cleavage sites identified, and the proposed antibacterial region is underlined.

The LL-37 degradation products lack bactericidal activity.

It has been shown that some truncated forms of LL-37 retain the peptide's antimicrobial effect (54). Thus, the antimicrobial capacity of the LL-37 low-MW derivative, obtained after subjecting LL-37 to hydrolysis with T. denticola TD4 supernatants, was tested. Figure 7 shows that T. denticola dentilisin inactivated the antimicrobial capacity of LL-37 and enabled the growth of E. coli and the survival of T. denticola cells.

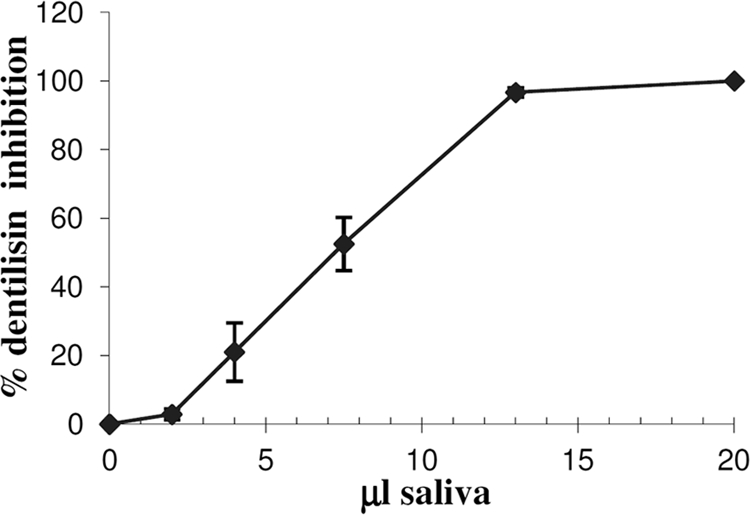

Saliva inhibits the proteolytic activity of dentilisin.

Saliva was previously shown to protect LL-37 from degradation by Porphyromonas gingivalis (33). As can be seen in Fig. 5, saliva completely inhibited the degradation of LL-37 by the T. denticola supernatant (Fig. 5Af) or by purified dentilisin (Fig. 5Bc). Human saliva also inhibited the hydrolysis of succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-p-nitroanilide (SAAPNA), a chromogenic substrate for the T. denticola dentilisin, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 8). Bovine serum albumin, at the protein concentration of saliva (2 mg/ml), did not inhibit the activity of purified dentilisin (data not shown), excluding a nonspecific competitive inhibitory phenomenon and demonstrating for the first time the existence of a yet-to-be-identified salivary dentilisin inhibitor.

Fig 8.

Inhibition of dentilisin by saliva is dose dependent. A total of 2 × 10−3 units of purified dentilisin were preincubated with increasing volumes of cleared saliva at room temperature for 20 min. Dentilisin activity was determined by cleavage of the chromogenic substrate SAAPNA. The data are means and standard deviations for two independent experiments performed in duplicate.

DISCUSSION

Deficiency in the production and processing of LL-37 in patients with morbus Kostmann (61) or with Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome (15) has been associated with early development of severe periodontitis. These clinical observations strongly suggest the importance of LL-37 in the protection of gingival tissues against bacterial challenge.

T. denticola is an oral spirochete closely associated with periodontal disease (70). In agreement with an earlier report (38), we found that T. denticola is susceptible to LL-37 with a minimum growth-inhibitory concentration of 50 μg/ml (11 μM). In previous reports, LL-37 concentrations in the oral cavity reached 0.5 μg/ml in the saliva (2) of healthy individuals and 10 μg/ml in the gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) of periodontitis patients (73). These concentrations appear lower than those found necessary here to completely inhibit the growth of T. denticola (50 μg/ml). However, saliva and GCF are constantly secreted, and therefore continuously newly secreted LL-37 is likely to accumulate on the pathogen's membrane and to reach bactericidal concentrations.

We also found that the major surface protein of T. denticola facilitates the initial attachment of LL-37 to the treponeme surface, thus reducing the bacteria's resistance to LL-37 (Fig. 2 to 4). Dentilisin is able to degrade LL-37 to lower-molecular-weight derivatives that lack antimicrobial activity (Fig. 5 to 7). However, the proteolytic activity of dentilisin fails to provide T. denticola with resistance to LL-37. This was concluded because the T. denticola wild-type strain TD4 and the protease-deficient mutant K1 showed similar susceptibilities to LL-37 (Fig. 2). It has been reported that the binding of LL-37 to phospholipid vesicles protects LL-37 from cleavage by proteinase K (57), while there is no protection if the vesicles are added after the addition of the protease. Our data suggest that binding of LL-37 to the treponemal surface may protect the peptide from inactivation by dentilisin, and thus, disruption of the treponemal membrane precedes potential inactivation of LL-37 by dentilisin. A similar mechanism was suggested for P. gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia, which were found to be susceptible to cecropin B (derived from silk moth), despite their ability to cleave the peptide (17). T. forsythia is also susceptible to LL-37 (42, 43) in spite of its high proteolytic capacity, including the presence of an active metalloproteinase (karylisin) capable of inactivating the antimicrobial activity of LL-37 (42).

It has been reported that T. denticola is relatively resistant (at concentrations up to 100 μg/ml) to human β-defensins (6, 7). Since the K1 mutant showed the same resistance to the peptides as the wild type, it was concluded that the dentilisin protease is not responsible for the resistance of T. denticola to β-defensins. Rather, decreased defensin binding (relative to that for susceptible organisms) and active efflux of the peptide were shown to be involved in the resistance to these peptides.

It is worth noting that the T. denticola K1 and MHE mutants are derived from wild-type T. denticola ATCC 35405 and not from the ATCC 35404 (TD4) strain used in this study. Nevertheless, these wild-type strains show high similarity with regard to their pathogenic behavior and the chemical composition of their virulence factors. These include similarity in the amino acid composition of MSP (greater than 90% identity) (27), in coaggregation and biofilm formation with P. gingivalis (77), and in resistance to β-defensins (7).

Previously, dentilisin was considered a chymotrypsin-like protease (50, 64, 74). Our mass spectrometric analysis shows that like other subtilisins (58), dentilisin displays a substrate specificity broader (restriction after Lys, Gln, and Val residues, in addition to Phe) than that previously reported. Analysis of dentilisin-treated LL-37 fragments shows that dentilisin cleaves predominantly Lys and Phe at the P1 position, though Gln and Val were also cleaved by the protease (Fig. 6A and B). Subtilisins display a preference for large hydrophobic groups at position P1 (31, 51). Nevertheless, in subtilisin BPN′ (GI 158262560), two modes of binding exist to accommodate either P1-Phe or P1-Lys substrates (59). The charged Lys was shown to form a salt bridge with Glu 156 to enable the Lys cleavage (58). Glu 156 is conserved at position 384 (GI 1752641) of dentilisin, supporting our data on the hydrolysis of Lys at position P1.

The products of dentilisin digestion are devoid of antimicrobial activity against T. denticola and E. coli cells (Fig. 7). These results could be expected from the analysis of the cleavage points of dentilisin, since the protease acted on the central (amphipathic α-helix) region of LL-37, to which antibacterial activity has been attributed (8, 23, 57).

In the present study (Fig. 5 and 8), we also discovered that saliva inhibits the proteolytic activity of dentilisin, thus ensuring the integrity and activity (both bactericidal and immunomodulatory) of LL-37. This finding, together with the in vitro observation that dentilisin inactivation does not increase susceptibility to LL-37 (Fig. 2), diminishes the role of dentilisin in the resistance of T. denticola to LL-37 in vivo. T. denticola and P. gingivalis are found in low numbers in early-developing, saliva-exposed supragingival plaque (44). Immunohistochemical localization of T. denticola and P. gingivalis in subgingival plaque of extracted periodontally diseased teeth showed low numbers of both bacteria in the subgingival margin, while the levels of these bacteria increased with the depth of the periodontal pocket (40). Thus, in the early stages of plaque development, LL-37 degradation by proteases of both these oral bacteria may be prevented by saliva through two different mechanisms: (i) inhibition of the T. denticola dentilisin proteolytic activity (Fig. 5 and 8) and (ii) protection of LL-37 from proteolytic degradation by Arg-gingipain, while its antibacterial activity is preserved (33). The salivary dentilisin inhibitory mechanism is also likely to hamper dentilisin-dependent nutrient acquisition by T. denticola. Work is in progress to determine whether gingival crevicular fluid is also capable of dentilisin inhibition.

The protease inhibitors α-1-antitrypsin, α-1-antichymotrypsin, leukocyte elastase inhibitor, and α-2-macroglobulin-like protein 1 were identified in whole saliva by proteomic mass spectrometry analysis (72). Nevertheless, among these inhibitors, some are completely degraded by dentilisin (30) and others are unable to inhibit the hydrolysis of low-molecular-weight substrates such as LL-37 or SAAPNA (22), as demonstrated in our study with the saliva dentilisin inhibitor. Studies are in progress to identify what appears to be a putative new salivary serine (subtilisin) protease inhibitor.

Gram-negative bacterial membranes are rich in acidic phospholipids and negatively charged lipopolysaccharides (46). It is generally accepted that the highly cationic LL-37 interacts by electrostatic forces with these anionic bacterial outer surface membrane components (14, 78). T. denticola, a Gram-negative anaerobic spirochete, lacks a typical LPS (68). MSP is an important virulence factor of T. denticola. In the present study, we show that the T. denticola mutant (MHE) lacking MSP is significantly more resistant to LL-37 (Fig. 2), and shows a lower level of binding of fluorescently labeled LL-37, than the wild-type strain TD4 (Fig. 3). In addition, MSP binds LL-37 (Fig. 4). The calculated pI of the MSP monomer is 6.34, and the native protein binds to an anion-exchange chromatography column at pH 7.4 (34), providing a possible explanation for the binding of the cationic LL-37 peptide to this virulence factor.

MSP is implicated in cytotoxicity (24, 75) and the adhesion of T. denticola to host cells (24), tissue proteins (19, 25), and other bacteria (62). In this study, we show that MSP can also serve as a prime target for the host defense peptides. LL-37 in sublethal concentrations is likely to bind MSP and inhibit its virulent activities. Moreover, reduction in MSP expression in order to escape LL-37 is expected to hamper the treponeme's virulence capacity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (grant 208/10).

We are very grateful to H. K. Kuramitsu and K. Honma for providing the T. denticola K1 mutant, to J. C. Fenno for the T. denticola MHE mutant, to G. Goshen for statistical analysis, and to O. Moshel for the MS-MS analysis.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 December 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Bachrach G, et al. 2008. Resistance of Porphyromonas gingivalis ATCC 33277 to direct killing by antimicrobial peptides is protease independent. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:638–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bachrach G, et al. 2006. Salivary LL-37 secretion in individuals with Down syndrome is normal. J. Dent. Res. 85:933–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bergsson G, et al. 2009. LL-37 complexation with glycosaminoglycans in cystic fibrosis lungs inhibits antimicrobial activity, which can be restored by hypertonic saline. J. Immunol. 183:543–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bernard JJ, Gallo RL. 2011. Protecting the boundary: the sentinel role of host defense peptides in the skin. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68:2189–2199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blakemore RP, Canale-Parola E. 1976. Arginine catabolism by Treponema denticola. J. Bacteriol. 128:616–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brissette CA, Lukehart SA. 2007. Mechanisms of decreased susceptibility to beta-defensins by Treponema denticola. Infect. Immun. 75:2307–2315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brissette CA, Lukehart SA. 2002. Treponema denticola is resistant to human beta-defensins. Infect. Immun. 70:3982–3984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burton MF, Steel PG. 2009. The chemistry and biology of LL-37. Nat. Prod. Rep. 26:1572–1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Capone R, et al. 2008. Human serum antibodies recognize Treponema denticola Msp and PrtP protease complex proteins. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 23:165–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chi B, Qi M, Kuramitsu HK. 2003. Role of dentilisin in Treponema denticola epithelial cell layer penetration. Res. Microbiol. 154:637–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chromek M, et al. 2006. The antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin protects the urinary tract against invasive bacterial infection. Nat. Med. 12:636–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cole JN, et al. 2010. M protein and hyaluronic acid capsule are essential for in vivo selection of covRS mutations characteristic of invasive serotype M1T1 group A Streptococcus. mBio 1:e00191-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Correia FF, et al. 2003. Two paralogous families of a two-gene subtilisin operon are widely distributed in oral treponemes. J. Bacteriol. 185:6860–6869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Curtis MA, et al. 2011. Temperature-dependent modulation of Porphyromonas gingivalis lipid A structure and interaction with the innate host defenses. Infect. Immun. 79:1187–1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Haar SF, Hiemstra PS, van Steenbergen MT, Everts V, Beertsen W. 2006. Role of polymorphonuclear leukocyte-derived serine proteinases in defense against Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect. Immun. 74:5284–5291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Devine DA, Cosseau C. 2008. Host defense peptides in the oral cavity. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 63:281–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Devine DA, Marsh PD, Percival RS, Rangarajan M, Curtis MA. 1999. Modulation of antibacterial peptide activity by products of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella spp. Microbiology 145(Pt 4):965–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Diamond G, Beckloff N, Weinberg A, Kisich KO. 2009. The roles of antimicrobial peptides in innate host defense. Curr. Pharm. Des. 15:2377–2392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Edwards AM, Jenkinson HF, Woodward MJ, Dymock D. 2005. Binding properties and adhesion-mediating regions of the major sheath protein of Treponema denticola ATCC 35405. Infect. Immun. 73:2891–2898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Egli C, Leung WK, Muller KH, Hancock RE, McBride BC. 1993. Pore-forming properties of the major 53-kilodalton surface antigen from the outer sheath of Treponema denticola. Infect. Immun. 61:1694–1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ellen RP, Dawson JR, Yang PF. 1994. Treponema denticola as a model for polar adhesion and cytopathogenicity of spirochetes. Trends Microbiol. 2:114–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Enghild JJ, Salvesen G, Thogersen IB, Pizzo SV. 1989. Proteinase binding and inhibition by the monomeric α-macroglobulin rat α1-inhibitor-3. J. Biol. Chem. 264:11428–11435 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Epand RF, Wang G, Berno B, Epand RM. 2009. Lipid segregation explains selective toxicity of a series of fragments derived from the human cathelicidin LL-37. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3705–3714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fenno JC, et al. 1998. Cytopathic effects of the major surface protein and the chymotrypsinlike protease of Treponema denticola. Infect. Immun. 66:1869–1877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fenno JC, Muller KH, McBride BC. 1996. Sequence analysis, expression, and binding activity of recombinant major outer sheath protein (Msp) of Treponema denticola. J. Bacteriol. 178:2489–2497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fenno JC, Wong GW, Hannam PM, McBride BC. 1998. Mutagenesis of outer membrane virulence determinants of the oral spirochete Treponema denticola. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 163:209–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fenno JC, et al. 1997. Conservation of msp, the gene encoding the major outer membrane protein of oral Treponema spp. J. Bacteriol. 179:1082–1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gaibani P, et al. 2010. The central region of the msp gene of Treponema denticola has sequence heterogeneity among clinical samples, obtained from patients with periodontitis. BMC Infect. Dis. 10:345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gorr SU. 2009. Antimicrobial peptides of the oral cavity. Periodontol. 2000 51:152–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grenier D. 1996. Degradation of host protease inhibitors and activation of plasminogen by proteolytic enzymes from Porphyromonas gingivalis and Treponema denticola. Microbiology 142(Pt 4):955–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gron H, Meldal M, Breddam K. 1992. Extensive comparison of the substrate preferences of two subtilisins as determined with peptide substrates which are based on the principle of intramolecular quenching. Biochemistry 31:6011–6018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gupta S, et al. 2010. Fusobacterium nucleatum-associated beta-defensin inducer (FAD-I): identification, isolation, and functional evaluation. J. Biol. Chem. 285:36523–36531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gutner M, Chaushu S, Balter D, Bachrach G. 2009. Saliva enables the antimicrobial activity of LL-37 in the presence of proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 77:5558–5563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Haapasalo M, Muller KH, Uitto VJ, Leung WK, McBride BC. 1992. Characterization, cloning, and binding properties of the major 53-kilodalton Treponema denticola surface antigen. Infect. Immun. 60:2058–2065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Imamura T. 2003. The role of gingipains in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. J. Periodontol. 74:111–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ishihara K, Kuramitsu HK, Miura T, Okuda K. 1998. Dentilisin activity affects the organization of the outer sheath of Treponema denticola. J. Bacteriol. 180:3837–3844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ishihara K, Miura T, Kuramitsu HK, Okuda K. 1996. Characterization of the Treponema denticola prtP gene encoding a prolyl-phenylalanine-specific protease (dentilisin). Infect. Immun. 64:5178–5186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ji S, et al. 2007. Susceptibility of various oral bacteria to antimicrobial peptides and to phagocytosis by neutrophils. J. Periodontal Res. 42:410–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Joly S, Maze C, McCray PB, Jr, Guthmiller JM. 2004. Human beta-defensins 2 and 3 demonstrate strain-selective activity against oral microorganisms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1024–1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kigure T, et al. 1995. Distribution of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Treponema denticola in human subgingival plaque at different periodontal pocket depths examined by immunohistochemical methods. J. Periodontal Res. 30:332–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kolenbrander PE, Parrish KD, Andersen RN, Greenberg EP. 1995. Intergeneric coaggregation of oral Treponema spp. with Fusobacterium spp. and intrageneric coaggregation among Fusobacterium spp. Infect. Immun. 63:4584–4588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Koziel J, et al. 2010. Proteolytic inactivation of LL-37 by karilysin, a novel virulence mechanism of Tannerella forsythia. J. Innate Immun. 2:288–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee SH, Jun HK, Lee HR, Chung CP, Choi BK. 2010. Antibacterial and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-neutralising activity of human cationic antimicrobial peptides against periodontopathogens. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 35:138–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li J, et al. 2004. Identification of early microbial colonizers in human dental biofilm. J. Appl. Microbiol. 97:1311–1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Loesche WJ, Grossman NS. 2001. Periodontal disease as a specific, albeit chronic, infection: diagnosis and treatment. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:727–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lugtenberg B, Van Alphen L. 1983. Molecular architecture and functioning of the outer membrane of Escherichia coli and other gram-negative bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 737:51–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mäkinen KK, Makinen PL. 1996. The peptidolytic capacity of the spirochete system. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 185:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mäkinen KK, Mäkinen PL, Loesche WJ, Syed SA. 1995. Purification and general properties of an oligopeptidase from Treponema denticola ATCC 35405—a human oral spirochete. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 316:689–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mäkinen PL, Mäkinen KK, Syed SA. 1994. An endo-acting proline-specific oligopeptidase from Treponema denticola ATCC 35405: evidence of hydrolysis of human bioactive peptides. Infect. Immun. 62:4938–4947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mäkinen PL, Mäkinen KK, Syed SA. 1995. Role of the chymotrypsin-like membrane-associated proteinase from Treponema denticola ATCC 35405 in inactivation of bioactive peptides. Infect. Immun. 63:3567–3575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Markland FJ, Smith E. 1971. Subtilisins: primary structure, chemical and physical properties, p 561–608 In Boyer PD. (ed), The Enzymes, 3rd ed, vol 3 Academic Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mathers DA, Leung WK, Fenno JC, Hong Y, McBride BC. 1996. The major surface protein complex of Treponema denticola depolarizes and induces ion channels in HeLa cell membranes. Infect. Immun. 64:2904–2910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McDowell JV, et al. 2011. Identification of the primary mechanism of complement evasion by the periodontal pathogen, Treponema denticola. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 26:140–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Murakami M, Lopez-Garcia B, Braff M, Dorschner RA, Gallo RL. 2004. Postsecretory processing generates multiple cathelicidins for enhanced topical antimicrobial defense. J. Immunol. 172:3070–3077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nizet V, et al. 2001. Innate antimicrobial peptide protects the skin from invasive bacterial infection. Nature 414:454–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nussbaum G, Ben-Adi S, Genzler T, Sela MN, Rosen G. 2009. Involvement of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in the innate immune response to Treponema denticola and its outer sheath components. Infect. Immun. 77:3939–3947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Oren Z, Lerman JC, Gudmundsson GH, Agerberth B, Shai Y. 1999. Structure and organization of the human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 in phospholipid membranes: relevance to the molecular basis for its non-cell-selective activity. Biochem. J. 341(Pt 3):501–513 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Perona JJ, Craik CS. 1995. Structural basis of substrate specificity in the serine proteases. Protein Sci. 4:337–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Poulos TL, Alden RA, Freer ST, Birktoft JJ, Kraut J. 1976. Polypeptide halomethyl ketones bind to serine proteases as analogs of the tetrahedral intermediate. X-ray crystallographic comparison of lysine- and phenylalanine-polypeptide chloromethyl ketone-inhibited subtilisin. J. Biol. Chem. 251:1097–1103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Puklo M, Guentsch A, Hiemstra PS, Eick S, Potempa J. 2008. Analysis of neutrophil-derived antimicrobial peptides in gingival crevicular fluid suggests importance of cathelicidin LL-37 in the innate immune response against periodontogenic bacteria. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 23:328–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Putsep K, Carlsson G, Boman HG, Andersson M. 2002. Deficiency of antibacterial peptides in patients with morbus Kostmann: an observation study. Lancet 360:1144–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rosen G, Genzler T, Sela MN. 2008. Coaggregation of Treponema denticola with Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum is mediated by the major outer sheath protein of Treponema denticola. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 289:59–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rosen G, Naor R, Kutner S, Sela MN. 1994. Characterization of fibrinolytic activities of Treponema denticola. Infect. Immun. 62:1749–1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rosen G, Naor R, Rahamim E, Yishai R, Sela MN. 1995. Proteases of Treponema denticola outer sheath and extracellular vesicles. Infect. Immun. 63:3973–3979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rother M, Bock A, Wyss C. 2001. Selenium-dependent growth of Treponema denticola: evidence for a clostridial-type glycine reductase. Arch. Microbiol. 177:113–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sambri V, et al. 2002. Comparative in vitro activity of five cathelicidin-derived synthetic peptides against Leptospira, Borrelia and Treponema pallidum. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:895–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. 2008. Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8:349–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Seshadri R, et al. 2004. Comparison of the genome of the oral pathogen Treponema denticola with other spirochete genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:5646–5651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Shah HN, Gharbia SE, Zhang MI. 1993. Measurement of electrical bioimpedance for studying utilization of amino acids and peptides by Porphyromonas gingivalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Treponema denticola. Clin. Infect. Dis. 16(Suppl. 4):S404–S407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent RL., Jr 1998. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J. Clin. Periodontol. 25:134–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Soren L, Nilsson M, Nilsson LE. 1995. Quantitation of antibiotic effects on bacteria by bioluminescence, viable counting and quantal analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 35:669–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sun X, Salih E, Oppenheim FG, Helmerhorst EJ. 2009. Activity-based mass spectrometric characterization of proteases and inhibitors in human saliva. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 3:810–820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Turkoglu O, Emingil G, Kutukculer N, Atilla G. 2009. Gingival crevicular fluid levels of cathelicidin LL-37 and interleukin-18 in patients with chronic periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 80:969–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Uitto VJ, Grenier D, Chan EC, McBride BC. 1988. Isolation of a chymotrypsinlike enzyme from Treponema denticola. Infect. Immun. 56:2717–2722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wang Q, Ko KS, Kapus A, McCulloch CA, Ellen RP. 2001. A spirochete surface protein uncouples store-operated calcium channels in fibroblasts: a novel cytotoxic mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 276:23056–23064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wilm M, Mann M. 1996. Analytical properties of the nanoelectrospray ion source. Anal. Chem. 68:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Yamada M, Ikegami A, Kuramitsu HK. 2005. Synergistic biofilm formation by Treponema denticola and Porphyromonas gingivalis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 250:271–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zasloff M. 2002. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 415:389–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zasloff M. 2002. Innate immunity, antimicrobial peptides, and protection of the oral cavity. Lancet 360:1116–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zhou Q, Leeman SE, Amar S. 2011. Signaling mechanisms in the restoration of impaired immune function due to diet-induced obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:2867–2872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]