Abstract

The outcome of infection depends on multiple layers of immune regulation, with innate immunity playing a decisive role in shaping protection or pathogenic sequelae of acquired immunity. The contribution of pattern recognition receptors and adaptor molecules in immunity to malaria remains poorly understood. Here, we interrogate the role of the caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 9 (CARD9) signaling pathway in the development of experimental cerebral malaria (ECM) using the murine Plasmodium berghei ANKA infection model. CARD9 expression was upregulated in the brains of infected wild-type (WT) mice, suggesting a potential role for this pathway in ECM pathogenesis. However, P. berghei ANKA-infected Card9−/− mice succumbed to neurological signs and presented with disrupted blood-brain barriers similar to WT mice. Furthermore, consistent with the immunological features associated with ECM in WT mice, Card9−/− mice revealed (i) elevated levels of proinflammatory responses, (ii) high frequencies of activated T cells, and (iii) CD8+ T cell arrest in the cerebral microvasculature. We conclude that ECM develops independently of the CARD9 signaling pathway.

INTRODUCTION

The tropical disease malaria, which is caused by intracellular protozoans of the genus Plasmodium, affects 250 million people and claims nearly 1 million lives annually (20). Disease pathogenesis is attributed to the blood stages of the parasite, and studies in rodent models have underscored the importance of proinflammatory cytokines and effector cells in triggering and exacerbating pathology (7). Yet, how innate sensing instructs immune responses to malaria remains ambiguous. Analogous to other infections, it is assumed that Plasmodium or Plasmodium-derived products are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which, after engagement, deliver signals to adaptor molecules that regulate the expression of cytokines and inflammatory responses in a coordinated way (5, 15).

The pathological outcome of infection of C57BL/6 mice with Plasmodium berghei ANKA, which mimics the fatal form of severe malaria known as cerebral malaria (1, 7), is referred to as experimental cerebral malaria (ECM). P. berghei ANKA-infected animals succumb to this severe disease by day 7 postinfection (p.i.). Mortality is characterized by immune pathology that is mediated by proinflammatory cytokines, such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (1, 9), as well as activated CD8+ T cells (2, 4). Current efforts aim at identifying the PRRs involved in the induction of these pathogenic effector responses. Early studies in this model have focused on the roles of the adaptor molecule myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88), which signals downstream of most Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in ECM development. However, effects of MyD88 deficiency, or single or multiple deletions of TLRs, have yielded controversial results, ranging from full protection against ECM (5, 10, 14) to no protection at all (17, 19). In addition, studies with the adaptor molecule Toll/interleukin 1 receptor (TIR) domain-containing adapter-inducing beta interferon (TRIF), which is downstream of TLR3 and TLR4, was found to be dispensable in ECM (5). Finally, mice lacking nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs) NOD-1 and -2, which signal through the adaptor molecule receptor interacting protein 2 (RIP2), develop ECM similar to controls despite decreased systemic IFN-γ levels (8). These results suggest involvement of pattern recognition pathways in ECM. Identification of these pathways could facilitate the development of immune-mediated strategies for ameliorating malaria infection.

Some C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), including dectin-1 and -2 and mincle, are PRRs that signal through the adaptor molecule CARD9 in combination with the tyrosine kinase Syk (16). CARD9 signaling was initially reported as vital for defense against the fungal pathogen Candida (11); Card9−/− mice fail to control early Candida infection that is associated with poor induction of inflammatory cytokines, including TNF, interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-2, and IL-17 (11, 16). CARD9 is also crucial for control of the intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes (12). More recently, CARD9 was shown to be essential for the early control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. CARD9 deficiency did not affect T cell responses against M. tuberculosis but led to aberrant granulocyte responses, including increased granulopoiesis and accelerated neutrophil recruitment to the inflamed lungs (6). Taken together, these results highlight the critical role of CARD9 in innate immunity to microbial infections. The role of CARD9 during parasitic infections has not been studied yet. Here, we investigated the potential role of CARD9 in ECM pathogenesis of acute malaria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Wild-type (WT) (C57BL/6) and Card9−/− mice were initially bred at the Third Medical Department, Technical University of Munich, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Munich, Germany. Mice between 6 and 12 weeks of age were used for experiments. Animal experiments were performed according to German Animal Protection Law, United Kingdom Home Office and European Regulations.

Card9−/− and WT mice were regularly checked, and homozygosity was confirmed by genotyping PCR using the following primers: KO_for (5′-CCATAGAGGACTATAGCTGCCTACAG-3′) and KO_rev (5′-GGGTGGGATTAGATAAATGCCTGCTC-3′) for the Card9 allele and WT_for (5′-TGAGAATGACGACGAGTGCTG-3′) and WT_rev (5′-CCGCTGCAGGATGTCCAGG-3′) for the CARD9 allele.

P. berghei ANKA and infections.

The complete life cycle of P. berghei ANKA was maintained at the Parasitology Unit, Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, Berlin, Germany. Infections were initiated with 104 infected red blood cells (iRBCs) or 104 sporozoites in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) delivered intravenously (i.v.). Parasitemia levels were determined by microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained blood smears.

Quantification of CARD9 transcripts in infected mice.

Sacrificed uninfected and P. berghei ANKA-infected mice (days 5 and 7) were perfused with PBS prior to the isolation of brains, spleens, and livers and the preparation of tissue homogenates. Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen), cDNA was prepared using the RETROscript kit (Ambion), and CARD9 expression was quantified by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR using SYBR green I master mix (Applied Biosystems). Quantification of GAPDH expression was used as the internal control. We used the following oligonucleotide primers (Eurofins MWG Operon): GAPDH (forward, 5′-TGAGGCCGGTGCTGAGTATGTCG-3′; reverse, 5′-CCACAGTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTG-3′) and CARD9 (forward, 5′-TGAGAATGACGACGAGTGCTG-3′; reverse, 5′-CCGCTGCAGGATGTCCAGG-3′).

Cytokine measurements.

The mouse inflammation cytometric bead array kit (BD Biosciences) was used to measure cytokine concentrations in plasma isolated from control and infected mice. Analysis was performed using an LSR II cell analyzer (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Characterization of spleen and brain leukocytes.

Cell suspensions were prepared from spleens isolated from control and infected mice. For phenotypic analysis of cellular activation, cells were surface stained for CD8 (clone 53.6-7), CD4 (clone GK1.5), CD11a (clone M17/4), and CD62L (clone MEL14). Antibodies were obtained from eBiosciences. For the analysis of IFN-γ production, cells were stimulated with antibodies to CD3 (145-2C11) and CD28 (37.51) for 5 h in the presence of brefeldin A. Cells were then surface stained for CD8 and CD4. Following fixation and permeabilization, cells were stained for intracellular IFN-γ. Brain-infiltrating lymphocytes were isolated as described previously (13).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical tests were computed with GraphPad Prism 5. Survival curves were compared by a log-rank (Mantel Cox) test. Statistical significance for mRNA expression levels was determined using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's posttest for multiple comparison analysis. Statistical significance for other figures was assessed using the Mann-Whitney test for nonparametric test samples (see the figure legends). A P value of <0.05 was taken as significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

CARD9 expression is modulated during P. berghei ANKA infection.

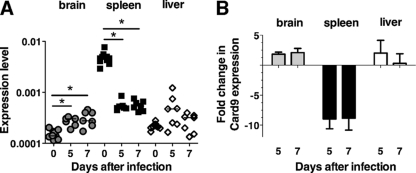

We first examined the expression pattern of CARD9 in brains, spleens, and livers of uninfected and P. berghei ANKA-infected WT mice by real-time PCR (Fig. 1). Baseline CARD9 expression was pronounced in the spleen (Fig. 1A). Consistent with previous findings, CARD9 expression was negligible in nonlymphoid organs, such as brain and liver (3, 12) (Fig. 1A). However, CARD9 expression in the spleens of P. berghei ANKA-infected WT mice was decreased 10-fold (days 5 and 7) and increased up to 2-fold (day 7) in the brains of infected WT mice (Fig. 1B). Thus, CARD9 expression is modulated during malaria, suggesting that this adaptor molecule may be involved in shaping immune responses leading to ECM.

Fig 1.

CARD9 expression during a Plasmodium berghei (strain ANKA) infection. RT-PCR of CARD9 expression was performed using total RNA isolated from brains, spleens, and livers of uninfected mice and on days 5 and 7 from P. berghei ANKA-infected mice and using primers specific for the CARD9 coding sequence. Results were normalized to amplification products using GAPDH primers. (A) Relative expression levels from two to three experiments. *, P < 0.05 following Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn's multiple comparison test. (B) Mean fold change shown as cumulative data from two experiments.

Card9−/− mice develop ECM similar to WT mice.

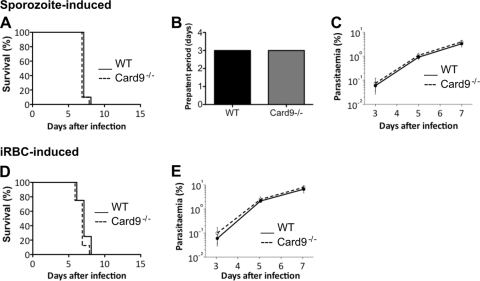

To evaluate whether CARD9 signaling was involved in the development of ECM, we compared the course of P. berghei ANKA infection in WT and Card9−/− mice following intravenous (i.v.) inoculation of 104 sporozoites (Fig. 2A to C) and infected red blood cells (iRBCs) (Fig. 2D and E).

Fig 2.

Card9−/− mice develop ECM similar to WT mice. (A) ECM development after sporozoite-induced infection by intravenous injection of 104 P. berghei ANKA sporozoites. Survival curves are based on cumulative data from two independent experiments, with five mice per group. (B) Time to blood stage infection (prepatency) after intravenous injection of 104 P. berghei ANKA sporozoites. (C) Parasitemia levels (for panel A) determined by Giemsa-stained blood smears. (D) ECM development after transfusion-mediated infection by intravenous injection of 104 P. berghei ANKA-infected red blood cells (iRBCs). Survival curves are based on cumulative data from three independent experiments, with four to six mice per group. (E) Parasitemia levels (for panel D) determined by Giemsa-stained blood smears.

Consistent with previous findings (14), both sporozoite-infected WT and Card9−/− mice succumbed to infection with a mean survival of 7 days. These animals displayed neurological signs associated with ECM, such as ataxia, paralysis, convulsion, or coma (Fig. 2A). Both groups of mice exhibited patent blood stage parasitemia on day 3 postinfection (Fig. 2B). There was no difference in the development of blood stage parasitemia between WT and Card9−/− mice (Fig. 2C). As with sporozoite-induced infections, iRBC-infected WT and Card9−/− mice also succumbed to infection on day 7 postinfection (Fig. 2D). No difference in the development of blood stage parasitemia between WT and Card9−/− mice infected with iRBCs was observed (Fig. 2E). To determine the integrity of the blood-brain barrier in infected WT and Card9−/− mice, Evans blue dye was injected i.v. into mice exhibiting neurological signs. Consistent with the clinical outcome of these animals, brains taken from day 7 infected WT and Card9−/− mice were permeable to the dye (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Together, our results indicate that CARD9 signaling is not involved in P. berghei ANKA-induced immune pathology.

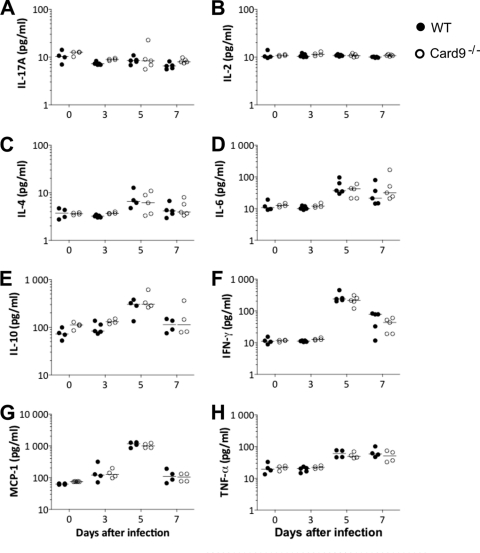

Card9−/− mice mount systemic cytokine responses comparable to WT mice.

As reported for P. berghei ANKA-infected nod1−/− × nod2−/− mice (8), the absence of innate immune signaling can alter the induction of systemic inflammation without affecting the development of ECM. Moreover, CARD9 signaling has been implicated in the induction of IL-17 responses to Candida infection (16), and it is not known whether IL-17 is induced following P. berghei ANKA infection. To this end, we collected plasma samples during the course of P. berghei ANKA infection in WT and Card9−/− mice and measured the levels of different cytokines and chemokines, namely, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17A, MCP-1, and TNF-α (Fig. 3). Upon P. berghei ANKA infection of both WT and Card9−/− mice, no appreciable increases in plasma concentrations of IL-17 and IL-2 were detected (Fig. 3A and B). There is a trend toward an increase in IL-4 on day 5 postinfection in both infected groups (Fig. 3C). In agreement with published data (14), concentrations of IL-6, IL-10, IFN-γ, MCP-1, and TNF-α (Fig. 3D to H) were significantly increased during the course of infection in WT mice, and infected Card9−/− mice had comparable levels of these cytokines. Plasma levels of IL-6, IL-10, IFN-γ, MCP-1, and TNF-α peaked on day 5 postinfection, irrespective of the presence of CARD9.

Fig 3.

Card9−/− mice display systemic cytokine responses similar to those of WT mice. Cytokine concentrations in plasma samples from infected mice. Cytokines were determined using the BD cytometric bead assay inflammation kit. Data shown are for IL-17 (A), IL-2 (B), IL-4 (C), IL-6 (D), IL-10 (E), IFN-γ (F), MCP-1 (G), and TNF-α (H). Day 0 represent data from uninfected mice. Figures show representative data from two to three experiments, four mice per group.

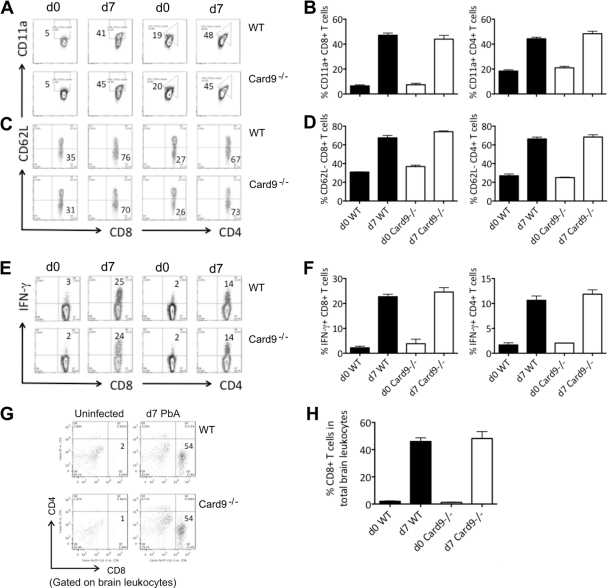

Systemic cellular responses and lymphocyte sequestration in the brain are CARD9 independent.

IFN-γ-secreting T cells as well as CD8+ T cells that are arrested in the cerebral microvasculature are vital effectors in ECM (1, 2, 4). To determine the contribution of CARD9 in T cell activation during P. berghei ANKA infection, single splenocyte suspensions were prepared from day 7 infected WT and Card9−/− mice (Fig. 4). The spleen cells were surface stained for the integrin molecule CD11a to quantify polyclonal populations of antigen-experienced T cells, particularly for CD8+ T cells (18) (Fig. 4A and B). Similar proportions of T cells (around 40% of the CD8+ and CD4+ T cells) from both infected WT and Card9−/− mice expressed CD11a. We also stained the spleen cells for the activation marker CD62L (L-selectin), which is downregulated in activated cells (Fig. 4C and D). We found no difference in the proportions of CD62Llo T cell populations in P. berghei ANKA-infected WT and Card9−/− mice.

Fig 4.

Systemic cellular responses and leukocyte sequestration to the brain in WT and Card9−/− mice infected with P. berghei ANKA. (A to D) High proportion of antigen-experienced CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in spleens after infection. Splenic leukocytes were isolated from uninfected mice and infected WT and Card9−/− mice on day 7 and surface stained for CD11a (A, B) or CD62L (C, D) and CD8+ or CD4+. (A, C) Shown are representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots displaying the proportions of CD11ahi (A) or CD62Llo (C) CD8+ (left) and CD4+(right) T cells before and 7 days after infection with 104 P. berghei ANKA-infected iRBCs. (B, D) Graphs show the percentage (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]) of CD11ahi or CD62Llo cells of total splenic CD8+ (left) and CD4+ (right) T cells before and 7 days after infection. Data are from one representative out of two experiments, with at least four mice per group. (E, F) High proportion of IFN-γ-producing cells in spleens after infection. Following splenic leukocyte isolation, cells were cultured with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies for 5 h in the presence of brefeldin A. Cells were subsequently stained for surface CD8+ or CD4+ and intracellular IFN-γ. (E) Shown are representative FACS plots displaying the proportions of IFN-γ+ CD8+ (left) and CD4+(right) T cells before and 7 days after infection with 104 P. berghei ANKA-infected iRBCs. (F) Graphs show the percentage (mean ± SEM) of IFN-γ+ cells of total splenic CD8+ (left) and CD4+ (right) T cells before and 7 days after infection. Data are from one representative out of two experiments, with at least four mice per group. (G, H) High proportion of infiltrating leukocytes in brains after infection. Brain-sequestered lymphocytes were isolated from uninfected and day 7 infected WT and Card9−/− mice. Cells were surface stained for CD8 and CD4. (G) Representative FACS plots show the proportions of CD8+ leukocytes before and 7 days after infection with 104 P. berghei ANKA-infected iRBCs. (H) Graphs show the percentage (mean ± SEM) of CD8+ leukocytes before and 7 days after infection. Data are from one representative out of three experiments, with at least four mice per group.

IFN-γ production by both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from P. berghei ANKA-infected WT and Card9−/− mice was determined after TCR ligation by CD3 and CD28 monoclonal antibodies (MAb) (Fig. 4E and F). Secretion and frequencies of activated T cells induced during P. berghei ANKA infection were also similar in WT and Card9−/− mice.

Finally, the arrest of CD8 T cells in the cerebral microvasculature is a cardinal feature of ECM. Therefore, we isolated brain-infiltrating lymphocytes from WT and Card9−/− mice at the time the animals suffered from neurological symptoms (day 7 postinfection) (Fig. 4G and H). As predicted from the clinical outcome, WT and Card9−/− mice revealed comparable proportions of sequestered CD8 T cells in the brain.

Concluding remarks.

We set out to study the roles of CARD9 in a lethal murine malaria model, since this molecule is the only key innate molecule identified thus far which is central to innate responses against eukaryotic pathogens (11). Our data show altered CARD9 expression during P. berghei infection, suggesting a potential role in ECM pathogenesis. However, both WT and Card9−/− mice developed ECM with similar features and kinetics. Both WT and Card9−/− mice succumbed to P. berghei ANKA infection and suffered from compromised blood-brain barrier integrity. In both mouse strains, proinflammatory responses and brain-infiltrating CD8 T cells were elevated. These findings are consistent with our observation that IL-17 plasma levels remain unaltered upon P. berghei ANKA blood infection. IL-17 is a key cytokine of T cells, which are activated in a CARD9-dependent fashion upon fungal infection (16). While pathogenic fungi are effectively controlled by CARD9-mediated immune responses, our study shows that Plasmodium-induced pathology occurs irrespective of the presence of CARD9.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

J.C.R.H. is supported by a Royal Society (United Kingdom) University Research Fellowship and a European Federation of Immunological Societies—Immunology Letters short-term fellowship. O.G. is supported by an EMBO long-term fellowship. This work was supported by the Max Planck Society and in part by the EviMalaR Network of Excellence (partner 34).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 12 December 2011

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Amani V, et al. 2000. Involvement of IFN-gamma receptor-mediated signaling in pathology and anti-malarial immunity induced by Plasmodium berghei infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:1646–1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Belnoue E, et al. 2002. On the pathogenic role of brain-sequestered alpha beta CD8+ T cells in experimental cerebral malaria. J. Immunol. 169:6369–6375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bertin J, et al. 2000. CARD9 is a novel caspase recruitment domain-containing protein that interacts with BCL10/CLAP and activates NF-kappa B. J. Biol. Chem. 275:41082–41086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Claser C, et al. 2011. CD8 T cells and IFN-gamma mediate the time-dependent accumulation of infected red blood cells in deep organs during experimental cerebral malaria. PLoS One 6:e18720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coban C, et al. 2007. Pathological role of Toll-like receptor signaling in cerebral malaria. Int. Immunol. 19:67–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dorhoi A, et al. 2010. The adaptor molecule CARD9 is essential for tuberculosis control. J. Exp. Med. 207:777–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Engwerda C, Belnoue E, Gruner AC, Renia L. 2005. Experimental models of cerebral malaria. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 297:103–143 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Finney CA, Lu Z, LeBourhis L, Philpott DJ, Kain KC. 2009. Disruption of Nod-like receptors alters inflammatory response to infection but does not confer protection in experimental cerebral malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 80:718–722 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grau GE, et al. 1989. Monoclonal antibody against interferon gamma can prevent experimental cerebral malaria and its associated overproduction of tumor necrosis factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:5572–5574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Griffith JW, et al. 2007. Toll-like receptor modulation of murine cerebral malaria is dependent on the genetic background of the host. J. Infect. Dis. 196:1553–1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gross O, et al. 2006. Card9 controls a non-TLR signalling pathway for innate anti-fungal immunity. Nature 442:651–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hsu YM, et al. 2007. The adaptor protein CARD9 is required for innate immune responses to intracellular pathogens. Nat. Immunol. 8:198–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Irani DN, Griffin DE. 1991. Isolation of brain parenchymal lymphocytes for flow cytometric analysis. Application to acute viral encephalitis. J. Immunol. Meth. 139:223–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kordes M, Matuschewski K, Hafalla JC. 2011. Caspase-1 activation of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 is dispensable for induction of experimental cerebral malaria. Infect. Immun. 79:3633–3641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krishnegowda G, et al. 2005. Induction of proinflammatory responses in macrophages by the glycosylphosphatidylinositols of Plasmodium falciparum: cell signaling receptors, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) structural requirement, and regulation of GPI activity. J. Biol. Chem. 280:8606–8616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. LeibundGut-Landmann S, et al. 2007. Syk- and CARD9-dependent coupling of innate immunity to the induction of T helper cells that produce interleukin 17. Nat. Immunol. 8:630–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lepenies B, et al. 2008. Induction of experimental cerebral malaria is independent of TLR2/4/9. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 197:39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rai D, Pham NL, Harty JT, Badovinac VP. 2009. Tracking the total CD8 T cell response to infection reveals substantial discordance in magnitude and kinetics between inbred and outbred hosts. J. Immunol. 183:7672–7681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Togbe D, et al. 2007. Murine cerebral malaria development is independent of Toll-like receptor signaling. Am. J. Pathol. 170:1640–1648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. World Health Organization 2009. Malaria report. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.