Abstract

Acinetobacter baumannii, which causes serious infections in immunocompromised patients, expresses high-affinity iron acquisition functions needed for growth under iron-limiting laboratory conditions. In this study, we determined that the initial interaction of the ATCC 19606T type strain with A549 human alveolar epithelial cells is independent of the production of BasD and BauA, proteins needed for acinetobactin biosynthesis and transport, respectively. In contrast, these proteins are required for this strain to persist within epithelial cells and cause their apoptotic death. Infection assays using Galleria mellonella larvae showed that impairment of acinetobactin biosynthesis and transport functions significantly reduces the ability of ATCC 19606T cells to persist and kill this host, a defect that was corrected by adding inorganic iron to the inocula. The results obtained with these ex vivo and in vivo approaches were validated using a mouse sepsis model, which showed that expression of the acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition system is critical for ATCC 19606T to establish an infection and kill this vertebrate host. These observations demonstrate that the virulence of the ATCC 19606T strain depends on the expression of a fully active acinetobactin-mediated system. Interestingly, the three models also showed that impairment of BasD production results in an intermediate virulence phenotype compared to those of the parental strain and the BauA mutant. This observation suggests that acinetobactin intermediates or precursors play a virulence role, although their contribution to iron acquisition is less relevant than that of mature acinetobactin.

INTRODUCTION

Acinetobacter baumannii is a Gram-negative opportunistic bacterial pathogen that has emerged as a serious threat to human health, particularly in hospitalized and/or immunocompromised patients (18, 36). Pneumonia has been the main manifestation of nosocomial infections caused by this pathogen that results in a significant impact on the mortality rate of patients (44). However, this microorganism has also been identified as the etiological agent responsible for a wide range of other infections, including septicemia, meningitis, and more recently, severe and deadly cases of necrotizing fasciitis (4, 9, 14, 36). In addition, the emergence of multiple-drug-resistant strains responsible for infections in susceptible populations, such as wounded military personnel returning from the Middle East, has also presented a significant problem to clinicians (1, 7). Many clinical isolates of A. baumannii exhibit a multiple- or pan-drug-resistant phenotype, limiting treatment options and creating a burden upon health care facilities (22, 23). Thus, the importance of identifying novel targets for the development of alternative antimicrobial therapies for these infections is a priority. However, the role A. baumannii virulence factors play in the pathogenesis of human infections remains largely obscure; therefore, the feasibility of these factors as therapeutic targets is uncertain. Recent work showed that A. baumannii interacts with human respiratory epithelial cells, an appropriate model considering the serious respiratory infections it causes in hospitalized patients, through cellular processes that involve the expression of bacterial cell surface components, such as the major outer membrane protein A (10, 11, 26). This surface-exposed protein plays a clear role in the abilities of A. baumannii to attach to, invade, and cause the apoptotic death of A549 human alveolar epithelial cell monolayers. A. baumannii clinical isolates, including the ATCC 19606T type strain, also cause deadly acute sepsis, pneumonia, and soft tissue infections when tested in murine experimental infections (30, 38) as well as the death of infected larvae of the greater wax moth Galleria mellonella (35). Taken together, these studies and observations indicate that A. baumannii is able to persist within an infected host by acquiring essential nutrients.

The host environment presents many nutritional possibilities as well as challenges that a bacterial pathogen must overcome. One of these challenges is the acquisition of iron, a micronutrient that is essential for almost all living cells (15). Although abundant in the human host, most of this metal is sequestered by high-affinity iron-binding chelators, such as hemoglobin, lactoferrin, and transferrin, with the purpose of avoiding cytotoxic effects due to the presence of free iron and controlling microbial infections through nonspecific mechanisms (6, 37, 47). To overcome this challenge, bacteria express a wide variety of high-affinity iron acquisition systems to scavenge iron from the host (16, 45). One such iron acquisition system, mediated by the biosynthesis and utilization of the siderophore acinetobactin, is produced by the A. baumannii ATCC 19606T type strain (20, 31). Our previous molecular genetic and functional analyses showed that the acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition system is the only fully active high-affinity iron acquisition system produced by this strain when cultured in iron-chelated bacteriological media (20), although recent genomic analyses showed that this strain harbors predicted genetic determinants capable of coding for additional iron acquisition systems (2, 21). Nevertheless, the relevance of iron acquisition functions expressed by A. baumannii in a biological system has not been explored.

This report shows that the ability of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T to persist inside A549 human alveolar epithelial cells and cause their apoptosis depends on the expression of active acinetobactin-mediated iron utilization functions and the production of the acinetobactin siderophore. Similarly, the infection and killing of mice and G. mellonella larvae depend on the ability of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T cells to express active acinetobactin biosynthesis and transport functions. These observations indicate that acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition is an important A. baumannii virulence factor, which could be used as a target for therapeutic purposes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, cell lines, and culture conditions.

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. Bacterial strains were routinely maintained in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or agar (40) at 37°C with appropriate antibiotics. Iron-rich and iron-chelated conditions were attained by supplementing LB broth with FeCl3 dissolved in 0.01 M HCl or with the synthetic iron chelator 2,2′-dipyridyl (DIP) to a final concentration of 100 μM. A549 human alveolar epithelial cells were maintained at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 using Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 IU of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Monolayers were cultured to 70% confluence before use in bacterial attachment and invasion assays.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) or usea | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| A. baumannii | ||

| ATCC 19606T | Clinical isolate; type strain | ATCC |

| 19606T-GFP | ATCC 19606T derivative producing GFP encoded by a gene on pMU125; Ampr | 19 |

| s1 | basD::aph; ATCC 19606T acinetobactin production-deficient derivative; Kmr | 20 |

| s1-GFP | s1 derivative producing GFP encoded by a gene on pMU125; Ampr | This work |

| t6 | bauA::EZ::TN<R6Kγori/KAN-2>; ATCC 19606T acinetobactin uptake-deficient derivative; Kmr | 20 |

| t6-GFP | t6 derivative producing GFP encoded by a gene on pMU125; Ampr | This work |

| E. coli | ||

| Top10 | Used for DNA recombinant methods | Invitrogen |

| DH5α | Used for DNA recombinant methods | Gibco-BRL |

| Plasmids | ||

| pWH1266 | E. coli-A. baumannii shuttle vector; Ampr Tcr | 27 |

| pMU125 | pWH1266 harboring gfp; Ampr | 19 |

Ampr, ampicillin resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Tcr, tetracycline resistance.

Interaction of bacteria with A549 alveolar epithelial cells.

To determine short-term bacterial attachment and invasion, 1 × 105 A549 cells were infected with 2 × 106 bacteria for 1 h at 37°C as described before (26). Bacteria attached to the surfaces of A549 cells were visualized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and micrograph observations were confirmed by counting the number of visible bacteria attached to A549 cells using five epithelial cells located in different fields from three different biological replicates. The number of intracellular bacteria was determined by plating appropriate dilutions of lysates obtained from gentamicin (Gm)-treated A549 infected cells (26). To determine intracellular bacterial persistence, A549 monolayers were infected with 5 × 103 bacteria suspended in 2 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution for 3 h at 37°C. Coinfections using two bacterial strains were done using a 2-ml mixture containing 5 × 103 cells of each strain. The infected monolayers were used to prepare lysates after Gm treatment as described before (26). To determine the total number of intracellular bacteria, appropriate lysate dilutions were plated on LB agar containing no antibiotics. To determine the number of intracellular s1 or t6 mutant cells, appropriate dilutions of A549 lysates were inoculated onto LB agar plates containing 40 μg/ml of kanamycin (Km). In all cases, the numbers of CFU were recorded after overnight (10 to 12 h) incubation at 37°C. Duplicate assays were done at least three times using fresh samples each time, and the data were statistically analyzed using the Student t test; P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Microscopy analysis of infected A549 cells.

The presence of intracellular bacteria was visualized with confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) of A549 cells infected with the ATCC 19606T-GFP strain or the s1-GFP or t6-GFP derivatives harboring pMU125, which codes for the production of green fluorescent protein (GFP). Bacterial cells (5 × 103) suspended in PBS were added to 1 × 105 epithelial cells and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Afterward, the monolayers were washed three times with prewarmed PBS, trypsinized, suspended in 1 ml of PBS, and stained with propidium iodide before being mounted onto a glass depression slide. The samples were visualized with a Zeiss 710 CLSM and analyzed using the Zen 2009 software package. The production of GFP was detected using the green filter set between 508 nm and 520 nm. The number of intracellular bacteria was determined by counting the number of green spots in 5 A549 cells in at least five different fields from each sample examined by CLSM. Counts were compared using the Student t test; P values < 0.05 were considered significant. Experiments were done at least twice using fresh biological samples each time.

Protein analysis.

To detect the production of the BauA acinetobactin receptor protein during the infection of A549 cells, monolayers were grown in 10 25-ml tissue culture flasks in 6 ml of supplemented DMEM. Epithelial cells were infected with 3 × 104 ATCC 19606T bacteria, which were grown overnight at 37°C in LB broth for 3 h at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 and then washed three times with prewarmed PBS, trypsinized, and collected by centrifugation. Cells were then lysed with sterile distilled water, and the internalized bacteria were collected by centrifugation, washed once with sterile PBS, and used to prepare bacterial total cell lysates as described before (43). Bacterial proteins were size fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using 12.5% gels, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with a polyclonal antibody against BauA as described before (20).

Evaluation of apoptosis using the TUNEL assay and epifluorescence microscopy.

A549 cell apoptosis was examined with the terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay (Promega, Madison, WI) as previously described (26). Briefly, infected epithelial cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h and then washed three times with PBS. Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X in PBS before the TUNEL reaction was performed. The reaction was stopped with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) provided in the kit. Samples were viewed using an Olympus AX70 epifluorescence microscope and were analyzed using the Metaview software package. The apoptosis rate was determined by counting the number of apoptotic foci (green spots) in 50 A549 cells in five different fields from each sample examined by epifluorescence microscopy. Counts were compared using the Student t test; P values < 0.05 were considered significant. Experiments were done at least twice in duplicate using fresh biological samples each time.

G. mellonella infection and killing assays.

Final-instar larvae (Vanderhorst, Inc., St. Mary's, OH) were stored in darkness at 25°C and used within 7 days of receipt. Infection experiments were performed as previously described (35). Briefly, caterpillars were evaluated for health and used in experiments based on three criteria: lack of melanization, movement in response to touch, and having a 250-mg- to 350-mg-mass range. Bacteria from overnight LB broth cultures were collected by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended in PBS alone or in PBS containing 100 μM FeCl3 as an exogenous iron source. All bacterial samples were adjusted to an appropriate cell density as determined by optical density at 600 nm. All bacterial inocula were confirmed by plating serial dilutions on LB agar and determining the number of CFU after overnight incubation at 37°C. The cuticle of the larva was swabbed gently with ethanol, and the hemocoel at the last left proleg was injected with 5-μl inocula containing from 100 to 106 bacterial cells ± 0.25 log using a syringe pump (New Era Pump Systems, Inc., Wantagh, NY) with a 26-gauge needle.

For infection assays, larvae were injected with 1 × 105 cells of the A. baumannii ATCC 19606T type strain or the s1 or t6 isogenic derivative. Larvae injected with sterile PBS were used as negative controls. After incubation at 37°C in darkness for 18 h, 30 responsive larvae from each experimental group were placed on ice for 10 min and briefly washed with 70% ethanol. Each larva was repeatedly washed with and homogenized in 1 ml of sterile distilled water containing 50 μg/ml vancomycin (Van). Homogenates were serially diluted with sterile distilled water containing 50 μg/ml Van, and 100-μl aliquots were plated on nutrient agar plates containing 50 μg/ml Van. CFU counts were done with an AlphaImager 2200 using the AlphaEase version 5.5 software package (Alpha Innotech Corporation-Cell Biosciences, Santa Clara, CA). Counts were compared using the Student t test; P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

For killing assays, each test series included control groups of noninjected larvae or larvae injected with 1 × 102 or 1 × 105 bacteria, sterile PBS, or PBS containing 100 μM FeCl3. The test groups included larvae infected with the parental strain ATCC 19606T or the isogenic derivative s1 or t6, all of which were injected in the presence or absence of 100 μM FeCl3. After injection, the larvae were incubated at 37°C in darkness, and the larvae were assessed at 24-h intervals over 6 days. Caterpillars were considered dead and removed from the study if they displayed no response to probing. The results of the trial were omitted if more than two deaths occurred in the control groups. The experiments were repeated six times using 10 larvae per experimental group, and the resulting survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method (28). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant for the log rank test of survival curves (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Mouse sepsis model.

Mice were housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions with free access to food and water. For infection studies, a previously described murine model of A. baumannii sepsis was employed (30). Briefly, inocula were prepared by inoculating 20 ml of Mueller-Hinton broth with a single colony of the indicated A. baumannii strains and incubating for 24 h at 37°C. Cultures were adjusted to the appropriate concentration with saline solution and combined 1:1 (vol/vol) with a 10% solution of porcine mucin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO; final mucin concentration of 5%). Dilutions of the inocula were plated on blood agar to determine final CFU values. For infection, female C57BL/6 mice between 14 and 16 weeks of age were injected intraperitoneally with 0.5 ml of the inocula using a 26-gauge needle (n = 6 mice/group). Tissue bacterial loads were determined 16 h after infection with the indicated inocula of the 19606T, s1, and t6 strains (n = 8 mice/group). Mice were euthanized with an overdose of thiopental, and their spleens were aseptically removed and homogenized after the addition of 2 ml of saline solution. Serial dilutions of tissue homogenates were plated on blood agar plates for quantification of viable bacteria after incubation at 37°C for 24 h. Colony counts were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test with a P value < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Animal survival was scored every 12 h for 7 days following infection. Survival between groups was compared using the log rank test with a P value < 0.05 considered statistically significant. All experiments involving the use of mice were approved by the University Hospital Virgen del Rocío Committee on Ethics and Experimentation.

RESULTS

Initial interaction of A. baumannii with human epithelial cells is independent of acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition functions.

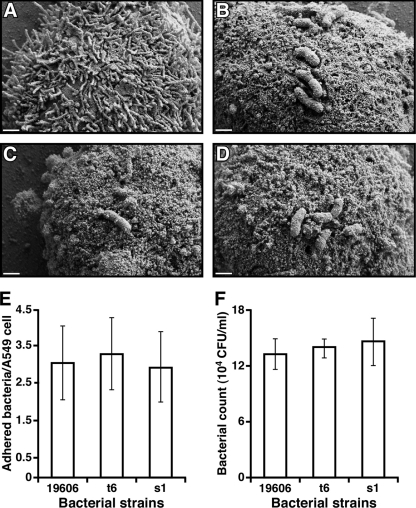

Based on our previous work showing the interaction of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T with A549 human respiratory cells (26), the role of the acinetobactin-mediated system in these interactions was tested using this type strain and the isogenic derivatives s1, affected in the expression of the BasD acinetobactin biosynthesis function, and t6, affected in the production of the BauA acinetobactin outer membrane receptor protein. SEM analysis showed that infection of A549 cells with 2 × 106 bacteria of each strain for a short time, 1 h, resulted in comparable cytotoxic effects, such as cell rounding and absence of surface appendages compared with the morphology of monolayers incubated in sterile medium (Fig. 1A to D). Visual inspection of micrographs of infected A549 cells and counting the number of visible bacteria attached to the A549 cells (Fig. 1E) showed comparable numbers of bacteria of each strain attached to the surfaces of epithelial cells. Furthermore, there were no statistically significant differences in the counts of intracellular bacteria of each tested strain (Fig. 1F). Taken together, these observations indicate that the acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition system does not play a major role in the initial interaction of the ATCC 19606T strain with human respiratory epithelial cells.

Fig 1.

Interaction of A. baumannii bacteria with A549 alveolar epithelial cells. (A) Sterile medium. (B to D) Adhesion of parental A. baumannii ATCC 19606T cells (B) or cells of the s1 acinetobactin production (C) or t6 utilization (D) isogenic derivatives examined by SEM after A549 cell monolayers were infected with 2 × 106 bacteria for 1 h. Bars, 1 μm. (E) Surface-attached bacterial counts collected from the SEM micrographs of infected monolayers, examples of which are shown in panels B to D. Data were collected using five A549 cells in different fields from three different biological replicates. Values are means ± 1 standard deviation (error bars). (F) Intracellular CFU counts obtained after lysates of Gm-treated A549 cells were plated on LB agar and incubated overnight at 37°C. Data represent three independent experiments done in duplicate each time. Values are means ± 1 standard deviation (error bars).

Bacterial intracellular persistence depends on the expression of the acinetobactin-mediated system.

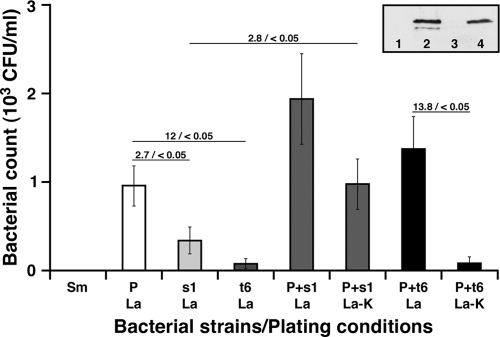

To determine whether bacterial persistence after the initial interaction with A549 cells depends on the expression of acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition functions, we repeated the studies described above but using a 3-h infection time. This approach failed to produce meaningful results perhaps because of the high infection dose used in those experiments. However, clear differences were observed when the monolayers were infected for 3 h with a lower bacterial dose, 5 × 103 cells. Under these conditions, the ATCC 19606T parental strain persisted significantly better than the s1 and t6 mutants, which showed a 2.7- and a 12-fold reduction in the number of intracellular bacteria, respectively, as determined after plating cell lysates on LB agar (Fig. 2, samples P La, s1 La, and t6 La). Figure 2 also shows that coinfection of A549 monolayers with 5 × 103 cells of the parental strain and the s1 mutant resulted in a 2-fold increase in the number of intracellular bacteria compared with the number of intracellular bacteria recovered from monolayers infected with only 5 × 103 cells of the parental strain (Fig. 2, compare P La and P+s1 La samples), with half of them being Km resistant (Fig. 2, compare P+s1 La and P+s1 La-K samples). However, the number of Km-resistant colonies recovered from monolayers coinfected with the parental strain and the s1 mutant were 2.8-fold higher than the number of colonies recovered from epithelial cells singly infected with s1 mutant bacteria (Fig. 2, compare P+s1 La-K and s1 La samples). This result indicates that the parental strain was able to trans-complement the s1 mutant by providing it with acinetobactin produced intracellularly. In contrast, no biological complementation was observed with the t6 mutant, which produces but does not transport ferric acinetobactin, when coinfected with parental cells. Plating lysates of A549 monolayers coinfected with ATCC 19606T and t6 bacteria on LB agar containing Km resulted in a 13.8-fold reduction in CFU counts compared with the counts obtained by plating these lysates on LB agar (Fig. 2, compare P+t6 La and P+t6 La-K samples). Furthermore, the t6 cell counts obtained on LB agar from singly infected monolayers were comparable with those obtained on LB agar containing Km from monolayers coinfected with ATCC 19606T and t6 bacteria (Fig. 2, compare t6 La and P+t6 La-K samples). The expression of the acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition system by intracellular bacteria was further tested by examining the production of the acinetobactin outer membrane receptor protein BauA. Immunoblotting of bacterial total lysates showed that ATCC 19606T cells produce BauA when they are inside A549 cells but not when incubated in supplemented DMEM culture medium used to grow the monolayers (Fig. 2, inset). This response mimics that obtained when bacterial cells are cultured in LB broth under iron-chelated and iron-rich conditions, respectively. Considering these results and the fact that the infecting bacteria were cultured in LB broth, medium that has enough iron to repress the production of BauA (33), the detection of BauA in bacteria isolated from infected epithelial cells indicate that this protein is produced in response to the iron-limiting conditions imposed by the A549 intracellular environment.

Fig 2.

Role and expression of the acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition functions by intracellular bacteria. A549 monolayers were incubated with sterile medium (Sm) or infected for 3 h with 5 × 103 cells of the ATCC 19606T parental strain (P) or cells of the s1 or t6 mutant. Monolayers were also coinfected with 5 × 103 cells of the parental strain mixed with equal number of cells of the s1 or t6 isogenic derivative. CFU counts were obtained after Gm-treated A549 cell lysates were plated on LB agar (La) and LB agar containing 40 μg/ml Km (La-K) to determine total bacterial and mutant cell counts, respectively. (Inset) Detection of the acinetobactin outer membrane receptor protein BauA. A. baumannii ATCC 19606T whole-cell lysates were prepared from cells cultured in supplemented DMEM (lane 3) or from intracellular bacteria recovered after infection of epithelial cells (lane 4). Protein samples loaded in lane 1 or 2, which were prepared from bacteria cultured in LB broth containing 100 μM FeCl3 or 100 μM DIP, respectively, were used as a control for differential production of BauA in response to free-iron availability. Horizontal bars with numbers indicate the fold change before the slash and the P value for the compared samples after the slash. Values are means ± 1 standard deviation (error bars).

Taken together, all the observations made using the A549 epithelial cell infection assays indicate that the acinetobactin-mediated iron transport system is not only expressed by A. baumannii ATCC 19606T intracellular bacteria but also show that this iron acquisition system is needed for bacterial intracellular persistence.

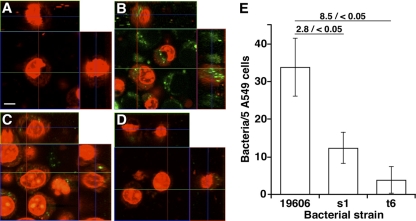

Microscopy analysis of A. baumannii-A549 cell interactions.

The interaction of bacteria with A549 epithelial cells was also examined by CLSM using isogenic strains producing GFP, encoded by a gene on the recombinant plasmid pMU125. This approach showed that after infection, numerous 19606T-GFP green fluorescent bacteria are located in the A549 cytoplasmic compartment (Fig. 3B). In contrast, very few and almost no green fluorescent cells of the s1-GFP and t6-GFP isogenic mutants could be detected within the cytoplasm of A549 cells in single-strain infection experiments, respectively (Fig. 3C and D). The microscopy observations were confirmed by visually counting the number of intracellular fluorescing bacteria. There was a 2.8- and a 8.5-fold reduction in the number of green foci representing s1-GFP and t6-GFP cells compared with the 19606T-GFP parental strain, respectively, in epithelial cells infected with a single strain (Fig. 3E). These observations confirm the ability of ATCC 19606T bacteria to localize and persist within the cytoplasmic space of the A549 alveolar epithelial cells in a manner that depends on the expression of an active acinetobactin-mediated iron uptake system.

Fig 3.

CLSM analysis of A549 monolayers infected with A. baumannii ATCC 19606T isogenic strains. (A to D) Monolayers were infected with ATCC 19606T-GFP (B), s1-GFP (C), or t6-GFP (D) cells, using uninfected monolayers (A) as a negative control. Production of GFP was detected using a green filter. All monolayers were stained with propidium iodide, which was detected using a red filter. All images were taken at a magnification of ×630, and Z stack analysis was performed at 0.63 μM increments. Bar, 20 μm. (E) Graphic representation of intracellular bacterial counts. Horizontal bars with numbers indicate the fold change before the slash and the P value for the compared samples after the slash. Values are means ± 1 standard deviation (error bars).

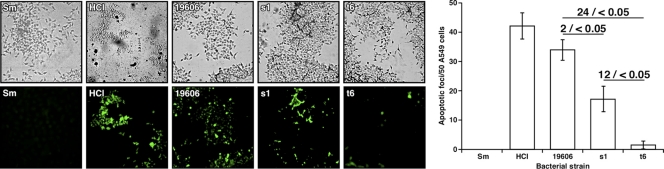

Apoptosis of A549 alveolar epithelial cells in response to bacterial infection.

Our previous report showed that A. baumannii ATCC 19606T induces apoptosis in A549 epithelial cells (26). To test whether the expression of iron acquisition functions might be involved in this process, the capacity of the s1 and t6 derivatives to induce apoptosis was compared to that of the ATCC 19606T parental strain using TUNEL assays. As expected from our previous work (26), infection of A549 monolayers with A. baumannii ATCC 19606T cells resulted in detectable apoptosis, as it was observed in the presence of HCl (Fig. 4, micrographs and bar graph). An apoptotic response was also observed when the monolayers were infected with the acinetobactin production mutant s1, although the number of apoptotic foci was reduced by 2-fold compared with the response obtained with the ATCC 19606T parental strain. A drastic apoptosis reduction (24-fold) was detected when the A549 epithelial cells were infected with acinetobactin receptor mutant t6 bacterial cells. Taken together, these results indicate that bacteria expressing fully active acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition functions cause more cell damage than bacteria deficient in either biosynthesis or transport of the acinetobactin siderophore.

Fig 4.

A549 apoptotic response to bacterial infection determined by TUNEL assays and fluorescence microscopy. A549 monolayers were infected with cells of the ATCC 19606T parental strain (19606), the s1 acinetobactin synthesis mutant, or the t6 acinetobactin transport mutant. A549 cells incubated in the presence of sterile medium (Sm) and sterile medium supplemented with 2 M HCl were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Samples were examined by fluorescence microscopy at a magnification of ×400 or ×600. (Right) Bar graph of the number of apoptotic foci determined from the cognate micrographs captured with fluorescence microscopy. Horizontal bars with numbers indicate the fold change before the slash and the P value for the compared samples after the slash. Values are means ± 1 standard deviation (error bars).

Infection and killing of G. mellonella larvae.

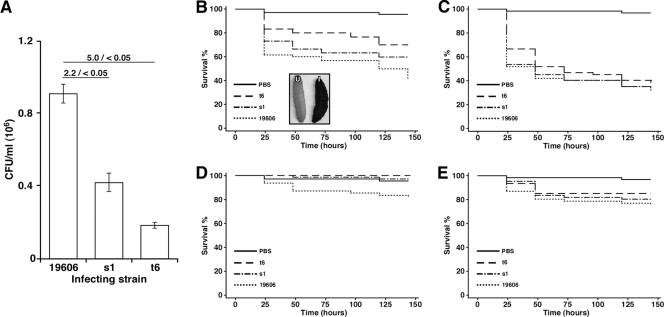

On the basis of a report describing the use of the greater wax moth G. mellonella to examine antibiotic efficacy against A. baumannii (35), we tested the role of acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition functions in this viable and convenient host model, which has been used to study other pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (32), Burkholderia mallei (41), and Burkholderia cepacia (42). As shown in Fig. 5A, the ATCC 19606T strain not only survived but also multiplied 18 h after the larvae were infected. In contrast, the number of bacteria recovered from infected larvae was reduced by 2.2- and 5.0-fold when caterpillars were injected with the s1 and t6 isogenic mutants, respectively. The inoculation of G. mellonella with A. baumannii ATCC 19606T resulted in killing of caterpillars in a time- and dose-dependent manner in a process that included melanization as described before using different A. baumannii clinical strains (35). Infection of caterpillars with 1 × 105 ATCC 19606T bacteria resulted in 40% death after 24 h inoculation, with more than half of the larvae dying by the sixth day, a response that is significantly different from that obtained with the PBS control (P = 0.0001) (Fig. 5B). The killing caused by the s1 and t6 derivatives was also significantly different (P = 0.0001) from this control. However, both mutants were less virulent than the parental strain, with t6 killing significantly fewer worms (P = 0.002) than ATCC 19606T, but s1 killing being intermediate and almost significantly different (P = 0.06) from that of the parental strain (Fig. 5B). The addition of 100 μM FeCl3 to the inocula made the killing rates of both mutants comparable to that of the ATCC 19606T parental strain, particularly during the last days of the experimental infection, with all of them being significantly different from the PBS control (P = 0.0001) (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, although the addition of inorganic iron to the inocula increased the killing rates during the early days of the infection, the numbers of caterpillars killed by all strains at the end of the experiment were statistically indistinguishable (P = 0.18) from that obtained without the supplementation of the inocula with FeCl3 (compare Fig. 5B and C). The lower infection dose of 1 × 102 ATCC 19606T bacterial cells resulted in a modest 20% total population death by the sixth day, a value that is statistically different (P = 0.008) from that recorded with the s1 and t6 mutants, which displayed a response indistinguishable from that of the controls injected with sterile PBS (Fig. 5D). However, the addition of an exogenous iron source resulted in comparable death rates by all three strains by the 48-h time point that remained close to 20%, a value that is significantly different (P = 0.0007) from the PBS control, until the end of the experimental infection (Fig. 5E). Taken together, these results indicate that the production of a fully active acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition system is required for full virulence of A. baumannii in the G. mellonella host.

Fig 5.

G. mellonella infection and killing assays. (A) For infection assays, caterpillars were injected with 1 × 105 bacteria of the ATCC 19606T parental strain (19606) or the s1 or t6 iron-deficient isogenic derivative and incubated at 37°C in darkness for 18 h. Dilutions of whole-larva lysates were plated on nutrient agar, and colony counts were determined after overnight incubation at 37°C. Horizontal bars with numbers indicate the fold change before the slash and the P value for the compared samples after the slash. Values are means ± 1 standard deviation (error bars). (B to E) For killing assays, caterpillars were infected with high (1 × 105 bacteria [B and C]) or low (1 × 102 bacteria [D and E]) bacterial doses in the absence (B and D) or presence (C and E) of 100 μM Fe3Cl. For negative controls, caterpillars were injected with comparable volumes of PBS (B and D) or PBS plus 100 μM Fe3Cl (C and E). The inset in panel B shows the melanization of infected caterpillars (I) and no pigmentation of uninfected (U) caterpillars.

Infection and killing of mice.

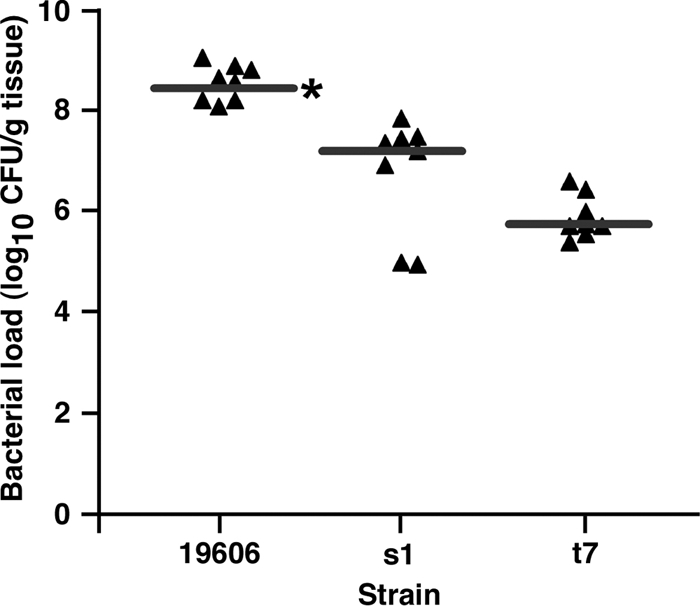

In order to evaluate the role of the acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition system in a mammalian host, we employed a previously characterized sepsis mouse model (30). This model produces an acute sepsis in which A. baumannii rapidly disseminates throughout the body to different organ systems. Importantly, mortality in this model has been shown to be dependent upon both the infecting A. baumannii strain and the number of bacteria in the inoculum, indicating that this model can be used to characterize differences in virulence between strains. Using this model, the ability of the ATCC 19606T, s1, and t6 strains to persist in infected animals was determined by measuring spleen bacterial loads 16 h after infection. As shown in Fig. 6, infection with the parental ATCC 19606T strain resulted in significantly higher spleen bacterial loads compared to both the s1 and t6 strains (medians of 8.6 versus 7.3 and 5.7, respectively; P < 0.001). Spleen bacterial loads in mice infected with the s1 strain showed a tendency toward being higher than in mice infected with the t6 strain; however, the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.093). These results indicate that the acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition system plays a role in bacterial survival when tested in an in vivo experimental model.

Fig 6.

Postinfection tissue bacterial loads in mice infected with the ATCC 19606T, s1, and t6 strains. C57BL/6 mice (n = 8 mice/group) were infected with ∼1 × 106 CFU of the indicated strain, and bacterial loads were measured in spleen homogenates 16 h postinfection. Each symbol represents the bacterial load from an individual mice, with the horizontal line indicating the median of the group. The asterisk indicates that the values for the ATCC 19606T parental strain (19606) and the s1 and t6 iron-deficient isogenic derivatives were statistically significantly different (P < 0.001).

In order to determine whether deficiencies in the acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition system also affect postinfection mortality, mice were infected with differing inocula (1.7 × 104 to 3.1 × 106 CFU) of the ATCC 19606T, s1, and t6 strains, and survival was measured. As shown in Table 2, all mice infected with the highest inoculum of the ATCC 19606T strain (1.9 × 106 CFU) succumbed to infection by 24 h. In contrast, infection with a similar inoculum of the s1 mutant (3.0 × 106 CFU) resulted in a mortality of 66.7%, with a mean time to death of 36.0 ± 13.9 h (P = 0.019). The t6 isogenic mutant also produced significantly less mortality compared to the ATCC 19606T parental strain with a similar inoculum (3.1 × 106 CFU), with no mice succumbing to infection within 7 days postinfection (P = 0.0009). Interestingly, comparison of mortality between the s1 and t6 strains also revealed that the s1 strain produced significantly higher mortality with a similar inoculum (approximately 3 × 106 CFU) than the t6 strain (P = 0.019). These results indicate that that the acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition system is required for full virulence in a mouse infection model and that lack of production of the BauA acinetobactin outer membrane receptor results in a more attenuated phenotype than a BasD acinetobactin biosynthesis deficiency.

Table 2.

Virulence of A. baumannii strains in a mouse sepsis model

| Strain | Inoculum (CFU) | Mortality (%)a | MTTDb (h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATCC 19606T | 1.9 × 106 | 100 | 24.0 ± 0.0 |

| 1.0 × 105 | 33.3 | 42.0c | |

| 1.7 × 104 | 0 | NA | |

| s1 | 3.0 × 106 | 66.7 | 36.0 ± 13.9 |

| 1.0 × 105 | 0 | NA | |

| 2.0 × 104 | 0 | NA | |

| t6 | 3.1 × 106 | 0 | NA |

| 3.5 × 105 | 0 | NA | |

| 2.9 × 104 | 0 | NA |

There were six mice in each group.

MTTD, mean time to death (hours). The mean ± standard deviation are shown. NA, not applicable due to no deaths in the group.

Calculation of the standard deviation was not possible because there were only two mice.

DISCUSSION

Although previous work showed that the ability of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T to grow under iron-chelated laboratory conditions depends on the expression of a fully active acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition system (20, 31), which is able to scavenge iron from transferrin and lactoferrin (48), this system's role in biological models that mimic the conditions this pathogen encounters in the human host has never been tested experimentally. Our data show that in contrast to bacterial adhesion and internalization roles played by some siderophore receptors, such as the IroN and IreA receptors produced by extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (24, 39), the absence of the BauA acinetobactin outer membrane receptor in the t6 derivative does not affect bacterial attachment and internalization in human alveolar epithelial cells after 1 h of infection. Similarly, the lack of acinetobactin production by the s1 mutant does not impair bacterium-A549 cell monolayer interactions, with both mutants producing a cytopathic response similar to that detected with the ATCC 19606T parental strain. This response could be due to the expression of bacterial functions other than those related to siderophore-mediated iron acquisition, such as the production of the outer membrane protein OmpA or unidentified OmpA-independent factors that cause alterations in cellular morphology and apoptotic death (26). In contrast to initial bacterium-A549 cell interactions, the ability of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T to persist within this epithelial cell type depends on the active production of acinetobactin and transport of ferric acinetobactin complexes as demonstrated by the intracellular cross-feeding of the s1 acinetobactin production-deficient derivative, but not the t6 acinetobactin transport mutant, by parental cells in coinfection assays. The detection of BauA in intracellular bacteria further supports this conclusion and confirms the role of the acinetobactin system as an important factor needed for persistence in human cells. All these observations are congruent with published reports indicating that the intracellular persistence and growth of some bacterial pathogens, such as Bacillus anthracis (8) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (17), depend on the expression of active siderophore-mediated systems that provide bacteria with essential iron while residing within human macrophages.

Considering the role the acinetobactin-mediated iron uptake system plays in the ability of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T to persist intracellularly, the differences in the A549 cell apoptotic response detected with the parental and isogenic iron uptake mutants could reflect the amount of intracellular bacteria actively producing apoptotic factors, such as OmpA (10, 11, 26), a condition that could determine the extent of cellular damage. Alternatively, these differences may reflect the amount of acinetobactin being produced and secreted by intracellular bacteria. The presence of ferriacinetobactin could contribute to cell injury by catalyzing the formation of damaging hydroxyl radicals in a manner similar to that described with P. aeruginosa ferripyochelin and A549 alveolar epithelial cells (5, 13). It is also possible that the capacity of intracellular bacteria to produce acinetobactin determines the extent of depletion of reduced glutathione and increase in iron limitation because of the presence of this siderophore. These types of responses were observed when neuroblastoma cells were treated with catechol (29), a chemical moiety present in the acinetobactin molecule. Certainly, these are interesting avenues that we plan to explore to gain a better understanding of the mechanisms by which acinetobactin could negatively affect the viability of host cells.

The critical role of the acinetobactin system is also evident when tested using more-complex experimental models that include host responses that pathogens must evade to persist and prosper after infection. Our data show that, unless free inorganic iron is in excess, ATCC 19606T acinetobactin production and utilization mutants are impaired in their ability to persist in and kill G. mellonella caterpillars, a response similar to that of Photorhabdus temperata. The capacity of this bacterium to grow under iron limitation and interact with insect hosts depends on the production and utilization of the catechol-based siderophore photobactin, conditions that are circumvented by adding inorganic iron to the growth media or the inocula (12, 46). It is interesting to note that the killing of caterpillars by the ATCC 19606T strain when injected with supplemental iron is faster than the response obtained with infections in which the inocula were not supplemented with inorganic iron, although the final numbers of dead worms are comparable over a 6-day time period under both conditions (compare Fig. 5B and C). These results can be attributed to the elimination of the initial growth constraints imposed by the G. mellonella iron sequestration functions. Similarly, the data obtained with the mouse sepsis model show that inactivation of acinetobactin biosynthetic and uptake functions drastically affect the capacity of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T to infect and kill this vertebrate host as shown by the data presented in Table 2 and Fig. 6. Taken together, all these observations lend support to our hypothesis that acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition functions are necessary for A. baumannii to facilitate pathogenesis in eukaryotic cells and organisms expressing nonspecific defense functions. Furthermore, our results show that the A549 tissue culture, G. mellonella, and mouse sepsis experimental infection systems are valid and convenient models to study the pathobiology of A. baumannii.

The results obtained with the three infection models used in this work indicate that the ability of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T to persist during infection of eukaryotic cells and invertebrate and vertebrate hosts that impose iron-limiting conditions depends on the production of a fully active acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition system. This observation supports our previous finding showing that the inactivation of acinetobactin biosynthetic or transport functions was enough to drastically reduce bacterial growth in laboratory media supplemented with the synthetic iron chelator DIP (20). Our results are also in agreement with the observation that DIP-mediated iron starvation induces the transcriptional expression of acinetobactin synthesis and transport genes as well as genes located in siderophore clusters 1 and 5 (21). However, the drastic growth attenuation of the s1 and t6 mutants in all three experimental models indicates that these gene clusters may not code for fully active iron uptake systems. Accordingly, cluster 5 contains only two predicted genes coding for potential enzymatic activities needed for 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHBA) biosynthesis, which could complement or overlap functions coded for genes located in the acinetobactin cluster or cluster 1. Although the latter cluster contains 11 predicted genes coding for putative siderophore biosynthesis and transport functions, our data are compatible with the hypothesis that this cluster may represent an incomplete system acquired from a source different from that related to the acinetobactin cluster and whose function in iron uptake remains to be tested and validated experimentally.

It is interesting to note that, with the exception of the data displayed in Fig. 1, all the results obtained with the three experimental models used in this work showed that, although significantly attenuated compared to the parental ATCC 19606T strain, the s1 acinetobactin synthesis mutant has an intermediate phenotype with respect to the t6 acinetobactin receptor mutant. This outcome could be due to an increased iron-chelated environment created by t6 cells producing but not using acinetobactin and therefore enhancing iron restriction and making residual intracellular iron unavailable for bacterial growth. This possibility is supported by our previous observation that the growth of the s1 mutant is less affected than the growth of the t6 derivative when cultured in chelated laboratory media (49). A similar outcome was obtained when Yersinia pestis derivatives defective in yersiniabactin biosynthesis and transport functions were compared using iron-deficient media, with the latter derivative being more iron sensitive than a yersiniabactin biosynthesis mutant (25). It is also possible that the enhanced phenotype of the s1 derivative compared to that of the t6 mutant could be due to the fact that the former mutant still produces acinetobactin intermediates and precursors such as DHBA, which showed intrinsic iron acquisition functions involved in virulence as in the case of Brucella abortus (3, 34). These precursors and intermediates could bind iron, although with less affinity than acinetobactin, and potentially serve as a source used by the s1 derivative to better persist and consequently cause more host injury than the t6 mutant. However, such a hypothesis implies that BauA could play a role in the recognition and transport of some of these intermediates and precursors if one considers the fact that the t6 mutant grows less efficiently than the s1 mutant when both derivatives are cultured under iron-chelated conditions. These possibilities will be tested by examining the iron uptake behavior and virulence response of an ATCC 19606T derivative in which inactivation of the entA gene would abolish the production of the acinetobactin precursor DHBA.

In summary, our results indicate that the success of A. baumannii ATCC 19606T as a pathogen capable of affecting invertebrate and vertebrate hosts and human epithelia depends on the production of an active acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition system, which allows bacteria to persist as well as to cause cell apoptosis and host killing. This property is most likely not restricted to the ATCC 19606T strain, since several A. baumannii sequenced and annotated genomes show the presence of the acinetobactin gene cluster. However, the presence of gene clusters coding for additional siderophore-mediated iron acquisition functions may indicate that the virulence of these isolates is independent of the expression of the acinetobactin-mediated system, a possibility that can be tested using the experimental infection models described in this report in combination with appropriate isogenic derivatives affected in iron acquisition functions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by funds from Public Health AI070174 and NSF 0420479 grants and Miami University research funds.

We are grateful to E. Lafontaine (College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Georgia) for providing the A549 cell line. We thank Richard Edelmann, Matt Duley, and the staff at the Miami University Center for Advanced Microscopy and Imaging for their help with electron and light/fluorescence microscopy. We also thank Xiao-Wen Cheng (Department of Microbiology, Miami University) for assistance with the technical design of G. mellonella experiments and Michael Hughes and the staff at the Miami University Statistical Consulting Center for the guidance provided during development and data analysis of the G. mellonella killing assays, respectively.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 January 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Abbott A. 2005. Medics braced for fresh superbug. Nature 436:758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Antunes LC, Imperi F, Towner KJ, Visca P. 2011. Genome-assisted identification of putative iron-utilization genes in Acinetobacter baumannii and their distribution among a genotypically diverse collection of clinical isolates. Res. Microbiol. 162:279–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bellaire BH, Elzer PH, Baldwin CL, Roop RM., II 2003. Production of the siderophore 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid is required for wild-type growth of Brucella abortus in the presence of erythritol under low-iron conditions in vitro. Infect. Immun. 71:2927–2932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brachelente C, Wiener D, Malik Y, Huessy D. 2007. A case of necrotizing fasciitis with septic shock in a cat caused by Acinetobacter baumannii. Vet. Dermatol. 18:432–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Britigan BE, Rasmussen GT, Cox CD. 1997. Augmentation of oxidant injury to human pulmonary epithelial cells by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa siderophore pyochelin. Infect. Immun. 65:1071–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bullen JJ, Rogers HJ, Spalding PB, Ward CG. 2005. Iron and infection: the heart of the matter. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 43:325–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Calhoun JH, Murray CK, Manring MM. 2008. Multidrug-resistant organisms in military wounds from Iraq and Afghanistan. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 466:1356–1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cendrowski S, MacArthur W, Hanna P. 2004. Bacillus anthracis requires siderophore biosynthesis for growth in macrophages and mouse virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 51:407–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Charnot-Katsikas A, et al. 2009. Two cases of necrotizing fasciitis due to Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:258–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Choi CH, et al. 2008. Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane protein A targets the nucleus and induces cytotoxicity. Cell. Microbiol. 10:309–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Choi CH, et al. 2005. Outer membrane protein 38 of Acinetobacter baumannii localizes to the mitochondria and induces apoptosis of epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 7:1127–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ciche TA, Blackburn M, Carney JR, Ensign JC. 2003. Photobactin: a catechol siderophore produced by Photorhabdus luminescens, an entomopathogen mutually associated with Heterorhabditis bacteriophora NC1 nematodes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4706–4713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Coffman TJ, Cox CD, Edeker B, Britigan BE. 1990. Possible role of bacterial siderophores in inflammation. Iron bound to the Pseudomonas siderophore pyochelin can function as a hydroxyl radical catalyst. J. Clin. Invest. 86:1030–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Corradino B, Toia F, di Lorenzo S, Cordova A, Moschella F. 2010. A difficult case of necrotizing fasciitis caused by Acinetobacter baumannii. Int. J. Low Extrem. Wounds 9:152–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Crichton R. 2009. Iron metabolism: from molecular mechanisms to clinical consequences, 3rd ed John Wiley & Sons Ltd, West Sussex, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 16. Crosa JH, Mey AR, Payne SM. 2004. Iron transport in bacteria. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 17. De Voss JJ, et al. 2000. The salicylate-derived mycobactin siderophores of Mycobacterium tuberculosis are essential for growth in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:1252–1257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H. 2007. An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:939–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dorsey CW, Tomaras AP, Actis LA. 2002. Genetic and phenotypic analysis of Acinetobacter baumannii insertion derivatives generated with a transposome system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6353–6360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dorsey CW, et al. 2004. The siderophore-mediated iron acquisition systems of Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606 and Vibrio anguillarum 775 are structurally and functionally related. Microbiology 150:3657–3667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eijkelkamp BA, Hassan KA, Paulsen IT, Brown MH. 2011. Investigation of the human pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii under iron limiting conditions. BMC Genomics 12:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Falagas ME, Bliziotis IA. 2007. Pandrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: the dawn of the post-antibiotic era? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 29:630–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Falagas ME, Rafailidis PI. 2007. Attributable mortality of Acinetobacter baumannii: no longer a controversial issue. Crit. Care 11:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Feldmann F, Sorsa LJ, Hildinger K, Schubert S. 2007. The salmochelin siderophore receptor IroN contributes to invasion of urothelial cells by extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli in vitro. Infect. Immun. 75:3183–3187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fetherston JD, Kirillina O, Bobrov AG, Paulley JT, Perry RD. 2010. The yersiniabactin transport system is critical for the pathogenesis of bubonic and pneumonic plague. Infect. Immun. 78:2045–2052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gaddy JA, Tomaras AP, Actis LA. 2009. The Acinetobacter baumannii 19606 OmpA protein plays a role in biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces and the interaction of this pathogen with eukaryotic cells. Infect. Immun. 77:3150–3160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hunger M, Schmucker R, Kishan V, Hillen W. 1990. Analysis and nucleotide sequence of an origin of DNA replication in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and its use for Escherichia coli shuttle plasmids. Gene 87:45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kaplan EL, Meier P. 1958. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete data. J. Am. Statist. Assn. 53:457–481 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lima RM, et al. 2008. Cytotoxic effects of catechol to neuroblastoma N2a cells. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 27:306–314 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McConnell MJ, et al. 2011. Vaccination with outer membrane complexes elicits rapid protective immunity to multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Infect. Immun. 79:518–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mihara K, et al. 2004. Identification and transcriptional organization of a gene cluster involved in biosynthesis and transport of acinetobactin, a siderophore produced by Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606T. Microbiology 150:2587–2597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miyata S, Casey M, Frank DW, Ausubel FM, Drenkard E. 2003. Use of the Galleria mellonella caterpillar as a model host to study the role of the type III secretion system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 71:2404–2413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nwugo CC, Gaddy JA, Zimbler DL, Actis LA. 2011. Deciphering the iron response in Acinetobacter baumannii: a proteomics approach. J. Proteomics 74:44–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Parent MA, Bellaire BH, Murphy EA, Roop RM, II, Elzer PH, Baldwin CL. 2002. Brucella abortus siderophore 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHBA) facilitates intracellular survival of the bacteria. Microb. Pathog. 32:239–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peleg AY, et al. 2009. Galleria mellonella as a model system to study Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenesis and therapeutics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2605–2609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. 2008. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21:538–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ratledge C. 2007. Iron metabolism and infection. Food Nutr. Bull. 28:S515–S523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Russo TA, et al. 2008. Rat pneumonia and soft-tissue infection models for the study of Acinetobacter baumannii biology. Infect. Immun. 76:3577–3586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Russo TA, Carlino UB, Johnson JR. 2001. Identification of a new iron-regulated virulence gene, ireA, in an extraintestinal pathogenic isolate of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 69:6209–6216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schell MA, Lipscomb L, DeShazer D. 2008. Comparative genomics and an insect model rapidly identify novel virulence genes of Burkholderia mallei. J. Bacteriol. 190:2306–2313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Seed KD, Dennis JJ. 2008. Development of Galleria mellonella as an alternative infection model for the Burkholderia cepacia complex. Infect. Immun. 76:1267–1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Smoot LM, Bell EC, Crosa JH, Actis LA. 1999. Fur and iron transport proteins in the Brazilian purpuric fever clone of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius. J. Med. Microbiol. 48:629–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Villegas MV, Hartstein AI. 2003. Acinetobacter outbreaks, 1977-2000. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 24:284–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wandersman C, Delepelaire P. 2004. Bacterial iron sources: from siderophores to hemophores. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58:611–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Watson RJ, Joyce SA, Spencer GV, Clarke DJ. 2005. The exbD gene of Photorhabdus temperata is required for full virulence in insects and symbiosis with the nematode Heterorhabditis. Mol. Microbiol. 56:763–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Weinberg ED. 2009. Iron availability and infection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1790:600–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yamamoto S, Okujo N, Kataoka H, Narimatsu S. 1999. Siderophore-mediated utilization of transferrin- and lactoferrin-bound iron by Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Health Sci. 45:297–302 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zimbler DL, et al. 2009. Iron acquisition functions expressed by the human pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii. Biometals 22:23–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]