Abstract

The bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes causes food-borne illnesses resulting in gastroenteritis, meningitis, or abortion. Listeria promotes its internalization into some human cells through binding of the bacterial surface protein InlB to the host receptor tyrosine kinase Met. The interaction of InlB with the Met receptor stimulates host signaling pathways that promote cell surface changes driving bacterial uptake. One human signaling protein that plays a critical role in Listeria entry is type IA phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase). The molecular mechanism by which PI 3-kinase promotes bacterial internalization is not understood. Here we perform an RNA interference (RNAi)-based screen to identify components of the type IA PI 3-kinase pathway that control the entry of Listeria into the human cell line HeLa. The 64 genes targeted encode known upstream regulators or downstream effectors of type IA PI 3-kinase. The results of this screen indicate that at least 9 members of the PI 3-kinase pathway play important roles in Listeria uptake. These 9 human proteins include a Rab5 GTPase, several regulators of Arf or Rac1 GTPases, and the serine/threonine kinases phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTor), and protein kinase C-ζ. These findings represent a key first step toward understanding the mechanism by which type IA PI 3-kinase controls bacterial internalization.

INTRODUCTION

Listeria monocytogenes is a food-borne bacterial pathogen capable of causing severe infections culminating in meningitis or abortion (70, 84). Listeria induces its own internalization (“entry”) into host cells that are normally nonphagocytic. The entry of Listeria into enterocytes and hepatocytes plays an important role in virulence by allowing bacteria to traverse the intestinal barrier (6, 44) and to colonize the liver (29). Another potential role for Listeria internalization is infection of the placenta (6), although this idea is controversial (89).

One of the major pathways of Listeria entry into host epithelial cells is mediated by the interaction of the bacterial surface protein InlB with its host receptor, the Met receptor tyrosine kinase (44, 78). InlB binds directly to the extracellular domain of Met, resulting in activation (tyrosine phosphorylation) of the receptor. Once activated, Met promotes signal transduction events that remodel the host cell surface, leading to bacterial engulfment (4, 5, 24, 45, 85). Host surface remodeling is driven, at least in part, by localized polymerization of actin. One of the human signaling proteins that acts downstream of Met to stimulate F-actin assembly and the internalization of Listeria is type IA phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase). Listeria infection induces localized activation of PI 3-kinase (24, 45). Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of type IA PI 3-kinase results in a reduction in InlB-mediated actin polymerization and bacterial entry (24, 45, 46). The molecular mechanism by which PI 3-kinase promotes Listeria internalization is not known.

Type IA PI 3-kinase is a heterodimeric enzyme composed of a 110-kDa catalytic subunit and an 85-kDa regulatory subunit (31). This PI 3-kinase controls a variety of processes in mammalian cells, including cell growth, survival, and motility. Type IA PI 3-kinase promotes its biological effects through at least two mechanisms. The best-understood mechanism involves lipid kinase activity. PI 3-kinase produces phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate [PI(3,4,5)P3], a lipid second messenger that binds a plethora of downstream “target” proteins (11, 31). PI(3,4,5)P3 recruits these target proteins to the plasma membrane, where they exert their biological activities. PI(3,4,5)P3 is converted by phosphatases to phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate [PI(3,4)P2], another lipid with signaling activity (11, 31). Apart from producing lipid second messengers, type IA PI 3-kinase can also regulate signal transduction through protein-protein interactions (15, 18, 40, 52).

In order to understand how type IA PI 3-kinase promotes the internalization of Listeria, it is critical to identify human proteins that act upstream and downstream of this kinase to control pathogen uptake. In this work, we describe an RNA interference (RNAi)-based genetic screen to identify components of the type IA PI 3-kinase signaling pathway involved in Listeria uptake. The 64 host genes targeted in this screen encode proteins that bind PI(3,4,5)P3 and/or PI(3,4)P2, proteins that interact with catalytic or regulatory subunits of PI 3-kinase, and proteins that are indirectly regulated by PI 3-kinase. Our findings indicate that at least nine human genes known to participate in type IA PI 3-kinase signaling are involved in Listeria entry. This work is an important first step in dissecting the molecular mechanism by which type IA PI 3-kinase mediates bacterial internalization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, mammalian cell lines, and media.

The Listeria monocytogenes strain BUG 947 was used for these studies. BUG 947 contains an in-frame deletion in the inlA gene and has normal expression of InlB (29). Consequently, BUG 947 is incapable of infecting HeLa or other host cells through interaction of the Listeria surface protein InlA with its host receptor, E-cadherin (24, 59, 78). Instead, this bacterial strain enters into host cells in a manner dependent on InlB and its host receptor, Met (24, 45, 78). The Listeria strain was grown in brain heart infusion (BHI; Difco) broth and was prepared for infection as described previously (46).

The human epithelial cell line HeLa (ATTC CCL-2) was grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 4.5 g of glucose per liter and 2 mM glutamine (catalog no. 11995-065; Invitrogen), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cell growth, cell stimulation, and bacterial infections were performed at 37°C under 5% CO2.

siRNAs.

The sequences of short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) used to target the human genes in the host type IA PI 3-kinase pathway are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. These siRNAs were designed by, and purchased from, Ambion or Sigma-Aldrich. As negative controls, two “nontargeting” siRNAs were used. These control siRNAs (nontargeting control 1 [catalog no. D-001210-01; Dharmacon] or nontargeting control 2 [catalog no. SIC001; Sigma-Aldrich]) contain two or more mismatches with all sequences in the human genome. Another control siRNA was directed against the nuclear gene encoding lamin A/C (5′-CUGAGAGCCGCAGCAGCUUtt-3′ [lowercase letters indicate nucleotide overhangs]).

Antibodies, inhibitors, and other reagents.

The polyclonal antibodies used were anti-mTor (catalog no. 2972; Cell Signaling), anti-phospholipase C-γ1 (catalog no. sc-81; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Rab5c (product no. HPA003426; Sigma-Aldrich), and anti-SWAP70 (catalog no. sc-81991; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The monoclonal antibodies used were anti-GIT1 (catalog no. 611396; BD Biosciences), anti-PDK1 (catalog no. 611070; BD Biosciences), anti-PSCD2 (anti-ARNO) (clone 6H5; product no. WH0009266M2; Sigma-Aldrich), and anti-α-tubulin (catalog no. T5168; Sigma-Aldrich). Horseradish peroxidase (HRPO)-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Jackson Immunolabs.

Transfection of HeLa cells with siRNA.

A total of 1.5 × 104 HeLa cells were seeded into wells of 24-well plates and were grown for approximately 24 h. Transfection with siRNA and the lipid reagent LF2000 (Invitrogen) was carried out as described previously (24, 34). In the experiments for which results are shown in Fig. 2 to 4, HeLa cells were transfected with pools of three different siRNA molecules for each target gene, except in the case of ILK or HRAS. Targeting of ILK or HRAS involved transfection with a pool of two siRNAs or a single siRNA, respectively. The two or three siRNAs used in each pool are numbered 1, 2, and 3 in Table S1 in the supplemental material. In the case of each siRNA pool (or of the single siRNA for HRAS), the final total concentration of siRNA was 100 nM. Control conditions for the experiments for which results are shown in Fig. 2 to 4 included mock transfection in the absence of siRNAs, transfection with 100 nM either of two “nontargeting control” (NTC) siRNAs, and transfection with a siRNA directed against the lamin A/C gene. For experiments involving single siRNA molecules (see Fig. 5), siRNAs were used at a final concentration of 100 nM. Control experiments employing a 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (63) indicated that control siRNAs or siRNA pools targeting each of the 64 target genes shown in Table 1 and Table S1 in the supplemental material did not affect the viability of HeLa cells 48 h after transfection.

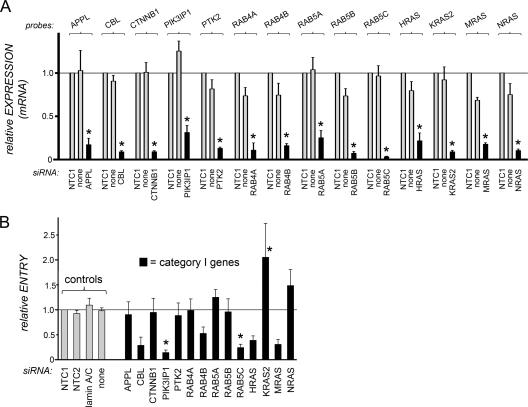

Fig 2.

Effects of siRNAs targeting category I host genes on gene expression and InlB-mediated Listeria entry. (A) Inhibition of host gene expression by siRNA pools. HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA pools targeting the indicated category I host genes. As controls, cells were transfected with a nontargeting control siRNA (NTC1) or were mock transfected in the absence of siRNAs (none). Approximately 48 h after transfection, cell lysates were prepared. Gene expression was analyzed by real-time PCR. Relative gene expression values were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Data are means ± SEM for 3 to 5 experiments, depending on the siRNA condition. Statistical analysis by ANOVA gave a P value of <0.0001. *, P < 0.05 relative to the NTC1 or no-siRNA control (by the Tukey-Kramer posttest). (B) Impact of siRNA pools on Listeria internalization into host cells. HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA pools directed against the indicated category I host gene. As controls, cells either were transfected with one of two nontargeting control siRNAs (NTC1, NTC2) or with a siRNA directed against lamin A/C or were mock transfected in the absence of siRNAs (none). About 48 h posttransfection, bacterial entry was assessed by using gentamicin protection assays. Relative entry values were obtained by normalization to entry in cells treated with the NTC1 control, as described in Materials and Methods. Data are means ± SEM. Results for siRNAs targeting category I genes are from 3 to 7 experiments, depending on the siRNA condition. Data obtained under the no-siRNA (none), NTC2, or lamin A/C siRNA control condition are from 46, 13, or 13 experiments, respectively. Statistical analysis by ANOVA gave a P value of <0.0001. *, P < 0.05 relative to the NTC1, NTC2, lamin A/C, or no-siRNA control (by the Tukey-Kramer posttest).

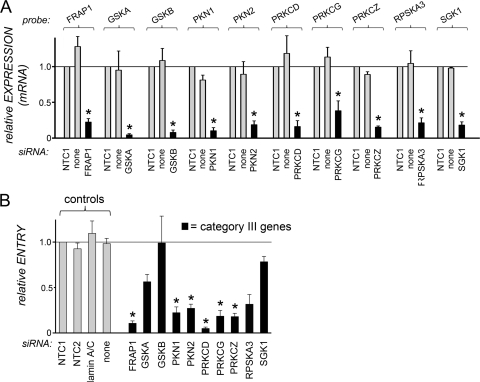

Fig 4.

Effects of siRNAs targeting category III host genes on human gene expression and entry of Listeria. (A) Inhibition of host gene expression. HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA pools targeting the indicated category III host genes. Control transfection conditions were those described in the legend for Fig. 2. For experiments with siRNAs targeting category III genes, data are means ± SEM for 3 to 5 experiments, depending on the siRNA condition. Statistical analysis by ANOVA gave a P value of <0.0001. *, P < 0.05 relative to the NTC1 or no-siRNA control (by the Tukey-Kramer posttest). (B) Impact of siRNA pools on Listeria entry. HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA pools directed against the indicated category III host genes. Control transfection conditions and measurement of bacterial entry were carried out as described in the legend for Fig. 2. Data for siRNAs targeting category III genes are means ± SEM for 3 to 7 experiments. Data obtained under the no-siRNA (none), NTC2, or lamin A/C siRNA control condition are from 46, 13, or 13 experiments, respectively. Statistical analysis by ANOVA gave a P value of <0.0001. *, P < 0.05 relative to the NTC1, NTC2, lamin A/C, or no-siRNA control (by the Tukey-Kramer posttest).

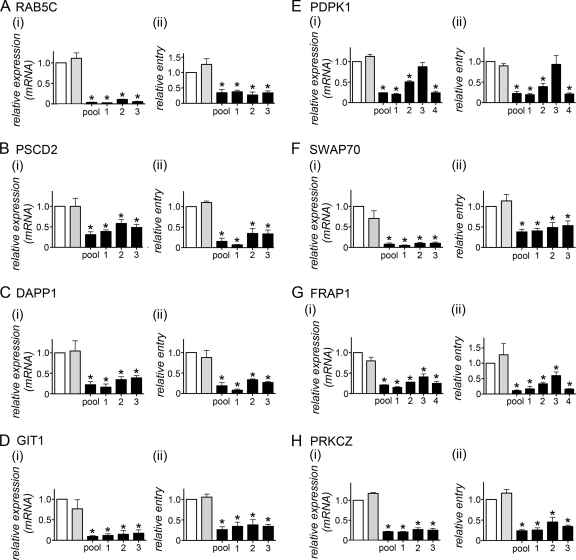

Fig 5.

Multiple siRNAs inhibiting target gene expression impair Listeria internalization. HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA pools or with an individual siRNA targeting the human gene indicated in each panel. Four individual siRNAs were tested for PDPK1 and FRAP1, whereas three siRNAs were tested for all other genes. As controls, cells either were mock transfected in the absence of siRNA (no siRNA) (open bars) or were transfected with control nontargeting siRNA 1 (NTC1) (shaded bars). (i) Effects of siRNAs on host gene expression. Gene expression was analyzed by real-time PCR. Data are means ± SEM for 3 to 4 experiments, depending on the siRNA condition. ANOVA gave P values of <0.0001 for RAB5C (A), PDPK1 (E), SWAP70 (F), FRAP1 (G), and PRKCZ (H), 0.0001 for GIT1 (D), 0.0003 for DAPP1 (C), and 0.0012 for PSCD2 (B). *, P < 0.05 relative to the no-siRNA or NTC1 control (by the Tukey-Kramer posttest). (ii) Effects of siRNA pools on Listeria internalization. Data are means ± SEM for 3 to 7 experiments, depending on the siRNA condition. Statistical analysis by ANOVA gave P values of <0.0001 for all data in all panels. *, P < 0.05 relative to the no-siRNA or NTC1 control (by the Tukey-Kramer posttest).

Table 1.

Genes targeted in the siRNA library

| Gene category and name | GenBank accession no. | Protein namea | Biochemical activityb | Biological function(s) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category I. Genes encoding proteins that bind subunits of type IA PI 3-kinase | |||||

| Rab GTPase genes | |||||

| RAB4A | NM_004578 | Rab4a | Rab GTPase; binds p85 regulatory subunit of PI 3-kinase | Receptor recycling, exocytosis | 15 |

| RAB4B | NM_016154 | Rab4b | Rab GTPase; binds p85 regulatory subunit of PI 3-kinase | Receptor recycling, exocytosis | 15 |

| RAB5A | NM_004162 | Rab5a | Rab GTPase; binds p85 and p110 subunits of PI 3-kinase | Endocytosis (formation and fusion of clathrin-coated vesicles) | 15 |

| RAB5B | NM_002868 | Rab5b | Rab GTPse; binds p85 and p110 subunits of PI 3-kinase | Endocytosis (formation and fusion of clathrin-coated vesicles) | 15 |

| RAB5C | NM_201434 | Rab5c | Rab GTPsae; binds p85 and p110 subunits of PI 3-kinase | Endocytosis (formation and fusion of clathrin-coated vesicles) | 15 |

| Ras GTPase genes | |||||

| HRAS | NM_004985 | H-Ras | Ras GTPase; binds and activates p110 catalytic subunit of PI 3-kinase | Actin cytoskeleton, cell growth | 12 |

| KRAS2 | NM_004985 | Ki-Ras2 | Ras GTPase; binds and activates p110 catalytic subunit of PI 3-kinase | Actin cytoskeleton, cell growth | 12 |

| MRAS | NM_012219 | M-Ras/R-Ras3 | Ras GTPase; binds and activates p110 catalytic subunit of PI 3-kinase | Actin cytoskeleton | 12 |

| NRAS | NM_002524 | N-Ras | Ras GTPase; binds and activates p110 catalytic subunit of PI 3-kinase | Actin cytoskeleton, cell growth | 12 |

| RRAS2 | NM_012250 | R-Ras2/TC21 | Ras GTPase; binds and activates p110 catalytic subunit of PI 3-kinase | Actin cytoskeleton | 12 |

| Miscellaneous | |||||

| APPL | NM_012096 | APPL | Adaptor protein; binds p110 | Enhancer of Akt1 activation | 61 |

| CBL | NM_005188 | Cbl | E3 ubiquitin ligase; binds p85 regulatory subunit of PI 3-kinase | Ubiquitination, receptor trafficking, actin cytoskeleton | 43, 83 |

| CTNNB1 | NM_001904 | Beta-catenin | Component of adherens junctions; binds p85 regulatory subunit of PI 3-kinase | Cell-cell junctions, transcriptional regulation | 90 |

| PIK3IP1 | NM_052880 | PI 3-kinase-interacting protein 1 | Transmembrane protein containing kringle motifs; binds and inhibits p110 catalytic subunit of PI 3-kinase | Apoptosis | 97 |

| PTK2 | NM_153831 | FAK/PTK2 | Cytosolic tyrosine kinase; binds p85 regulatory subunit of PI 3-kinase, stimulates PI 3-kinase activity | Cell adhesion and migration | 17 |

| Category II. Genes encoding proteins that bind PI(3,4,5)P3 and/or PI(3,4)P2 | |||||

| Ser/Thr kinases | |||||

| AKT1 | NM_005163 | Akt1/protein kinase B1 | Serine/threonine kinase; substrates include BAD, forkhead transcription factors, GSK-α, GSK-β, ERM proteins; PH domain binds PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 | Cell survival, growth, motility | 49, 58 |

| AKT2 | NM_001626 | Akt2/protein kinase B2 | Serine/threonine kinase; substrates likely the same as those of Akt1; PH domain binds PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 | Cell survival, growth, motility, insulin-induced glucose uptake, tumorigenesis | 49 |

| ILK | NM_004517 | Integrin-linked kinase | Serine/threonine kinase; substrates include MLC-20 and MYPT1; PH domain binds PI(3,4,5)P3 | Integrin-mediated cell adhesion and survival | 38 |

| PDPK1 | NM_002613 | PDK1 | Serine/threonine kinase; substrates include Akt, protein kinase C (PKC isoforms), PAK1, PAK2, p70S6 kinase, and SGK1; PH domain binds PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 | Cell survival, growth, motility, insulin signaling, T-cell differentiation | 3 |

| Regulators of Arf GTPases | |||||

| ARAP3 | NM_022481 | ARAP3/centaurin δ-3 | GAP for Arf6 and RhoA; binds PI(3,4,5)P3 through PH domains | Actin cytoskeleton, cell motility | 51 |

| CENTA1 | NM_006869 | Centaurin α-1 | GAP for Arf6; binds PI(3,4,5)P3, probably through PH domain(s) | Actin cytoskeleton, cell migration | 86 |

| CENTD1 | NM_139182 | ARAP2/centaurin δ-1 | GAP for Arf6; PI(3,4,5)P3 stimulates GAP activity, possibly by binding PH domain(s) | Actin cytoskeleton, focal adhesions | 93 |

| CENTD2 | NM_015242 | ARAP1/centaurin δ-2 | GAP for Arf1, Arf5, RhoA, and, Cdc42; PH domain binds PI(3,4,5)P3 | Golgi structure, actin cytoskeleton | 62 |

| GIT1 | NM_014030 | GIT1 | GAP for Arf1, Arf2, Arf3, Arf5, and Arf6; PI(3,4,5)P3 stimulates GAP activity | Actin cytoskeleton, focal adhesions, membrane trafficking | 41, 88 |

| GIT2 | NM_057169 | GIT2 | GAP for Arf1, Arf2, Arf3, Arf5, and Arf6; PI(3,4,5)P3 stimulates GAP activity | Actin cytoskeleton, focal adhesions, membrane trafficking | 41, 88 |

| PSCD1 | NM_004762 | Cytohesin-1/PSCD1 | GEF for Arf1 and Arf3; PH domain binds PI(3,4,5)P3 | Integrin-mediated cell adhesion | 26, 50 |

| PSCD2 | NM_017457 | ARNO/cytohesin-2, PSCD2 | GEF for Arf1 and Arf6; PH domain binds PI(3,4,5)P3 | Actin cytoskeleton, membrane trafficking, integrin recycling | 26, 87 |

| PSCD3 | NM_004227 | Grp1/cytohesin-3/PSCD3 | GEF for Arf1, Arf3, and Arf6; PH domain binds PI(3,4,5)P3 | Membrane trafficking, Golgi function, cell adhesion | 26, 55 |

| Regulators of Rac, and/or Cdc42 GTPases | |||||

| ARHGAP9 | NM_032496 | Rho-type GTPase-activating protein 9 | GAP for Cdc42 and Rac1; PH domain binds PI(3,4,5)P3 | Cell adhesion | 13 |

| ARHGEF6 | NM_004840 | α-PIX/Rac/Cdc42 GEF 6/Cool-2 | GEF for Rac and Cdc42 | Cell adhesion | 94 |

| DAPP1 | NM_014395 | DAPP1/Bam32 | Adaptor protein; enhances Rac activity; PH domain binds PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 | Actin cytoskeleton | 28 |

| DEPDC2 | NM_024870 | P-REX2/DEPDC2 | GEF for Rac | Actin cytoskeleton | 25 |

| DOCK1 | NM_001380 | Dock180 | GEF for Rac; DHR1 domain binds PI(3,4,5)P3 | Actin cytoskeleton, cell motility, phagocytosis | 20 |

| SOS1 | NM_005633 | Sos1 | GEF for Rac and Ras | Actin cytoskeleton, cell growth | 72 |

| SWAP70 | NM_015055 | SWAP70 | GEF for Rac | Actin cytoskeleton | 79 |

| TIAM1 | NM_003253 | Tiam1 | GEF for Rac; PH domain binds PI(3,4,5)P3 | Actin cytoskeleton, cell motility | 72 |

| VAV2 | NM_003371 | Vav2 | GEF for Rac; PH domain is thought to bind PI(3,4,5)P3 | Actin cytoskeleton | 36 |

| VAV3 | NM_006113 | Vav3 | GEF for Rac; PH domain is thought to bind PI(3,4,5)P3 | Actin cytoskeleton | 36 |

| Regulators of Ras GTPases | |||||

| RASA2 | NM_006506 | Gap1m | GAP for Ras; PH domain binds PI(3,4,5)P3 | Cell growth inhibitor | 92 |

| RASA3 | NM_007368 | Gap1/IP4BP | GAP for Ras and Rap; PH domain binds PI(3,4,5)P3 | Cell growth inhibitor | 92 |

| Lipid-modifying enzymes | |||||

| PLCG1 | NM_002660 | PLC-γ1 | Converts PI(4,5)P2 to IP3; PH domain binds PI(3,4,5)P3 | Actin cytoskeleton, cell growth, phagocytosis | 32 |

| PLD1 | NM_002662 | Phospholipase D1 | Converts phosphatidylcholine to phosphatidic acid, activated by PI(3,4,5)P3 or PI(3,4)P2; PH domain binds PI(3,4)P2 | Actin cytoskeleton, membrane trafficking | 71 |

| PLD2 | NM_002663 | Phospholipase D2 | Converts phosphatidylcholine to phosphatidic acid, activated by PI(3,4,5)P3 or PI(3,4)P2; PH domain binds PI(3,4)P2 | Actin cytoskeleton, membrane trafficking | 71 |

| Adaptor protein PLEKHA1 | NM_001001974 | PLEKHA1/TAPP1 | Adaptor protein; PH domain binds PI(3,4)P2 | Actin cytoskeleton, inhibition of insulin and PI 3-kinase pathways | 27 |

| Miscellaneous | |||||

| BMX | NM_203281 | Bmx/Etk | Tec family tyrosine kinase; PH domain binds PI(3,4,5)P3 | Cell growth, motility, apoptosis | 80 |

| MYOX | NM_012334 | Myosin X | Actin-dependent motor protein; PH domains bind PI(3,4,5)P3 | Contractility, phagocytosis | 21, 69 |

| SNX1 | NM_003099 | Sorting nexin-1 | PX domain binds PI(3,4,5)P3 | Endocytosis, receptor trafficking | 96 |

| SNX5 | NM_152227 | Sorting nexin-5 | PX domain binds PI(3,4)P2 | Endocytosis, receptor recycling from endosomes to the Golgi | 60 |

| Category III. Genes encoding proteins indirectly regulated by type IA PI 3-kinase | |||||

| FRAP1 | NM_004958 | mTor/FRAP1 | Ser/Thr kinase; regulated by Akt; substrates include Akt, PKC-α, PKC-δ, p70S6 kinase, SGK1 | Regulation of protein synthesis, cell migration | 33, 75, 91 |

| GSK3A | NM_019884 | Glycogen synthase kinase-3α | Regulates glycogen synthase; substrate of Akt proteins | Cell survival, tumorigenesis, regulation of gene expression | 75 |

| GSK3B | NM_002093 | Glycogen synthase kinase-3β | Regulates glycogen synthase; substrate of Akt proteins | Cell survival, tumorigenesis, regulation of gene expression | 75 |

| PAK1 | NM_002576 | PAK1 | Ser/Thr kinase; phosphorylated by PDK1 | Actin cytoskeleton, cell migration | 30 |

| PAK2 | NM_002577 | PAK2 | Ser/Thr kinase; phosphorylated by PDK1 | Actin cytoskeleton, cell migration | 30 |

| PKN1 | NM_213560 | Protein kinase N1 | Ser/Thr kinase; phosphorylated by PDK1; substrates include α-actinin, adducin, and cortactin | Actin cytoskeleton, cell migration, membrane trafficking, exocytosis | 64 |

| PKN2 | NM_006256 | Protein kinase N2 | Ser/Thr kinase; phosphorylated by PDK1; substrates include α-actinin, adducin, and cortactin | Actin cytoskeleton, cell migration, cell adhesion | 64 |

| PRKCD | NM_006254 | PKC-δ | Ser/Thr kinase; phosphorylated by PDK1 and mTor; substrates include MARCKS, ERM proteins, adducin | Actin cytoskeleton; cell migration | 53, 74 |

| PRKCE | NM_005400 | PKC-ε | Ser/Thr kinase; phosphorylated by PDK1 and mTor; substrates include MARCKS, ERM proteins, adducin | Actin cytoskeleton; cell migration | 53, 74 |

| PRKCG | NM_002739 | PKC-γ | Ser/Thr kinase; phosphorylated by PDK1; substrates include MARCKS, ERM proteins, adducin | Actin cytoskeleton; cell migration | 53, 74 |

| PRKCI | NM_002740 | PKC-ι | Ser/Thr kinase; substrate of PDK1; substrates include MARCKS, ERM proteins, adducin | Actin cytoskeleton | 53, 74 |

| PRKCQ | NM_006257 | PKC-θ | Ser/Thr kinase; phosphorylated by PDK1; substrates include MARCKS, ERM proteins, adducin | Actin cytoskeleton; cell migration | 53, 74 |

| PRKCZ | NM_002744 | PKC-ζ | Ser/Thr kinase; phosphorylated by PDK1; substrates include MARCKS, ERM proteins, adducin | Actin cytoskeleton, cell polarity | 53, 74 |

| RPS6KA1 | NM_002953 | P70S6 kinase 1/RSK1 | Substrate of PDK1; phosphorylates several transcription factors, including SRF and c-Fos | Regulation of translation, cell growth | 75 |

| RPS6KA3 | NM_004586 | P70 S6 kinase 2/RSK2 | Substrate of PDK1; phosphorylates several transcription factors, including SRF and c-Fos | Regulation of translation, cell growth | 75 |

| SGK1 | NM_005627 | Serum/glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 | Ser/Thr kinase; phosphorylated by PDK1 and mTor; substrates include NEDD4L and FOXO3A | Cell survival, ion transport | 10 |

FAK, focal adhesion kinase; PTK2, protein tyrosine kinase 2; PDK1, 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1; PLC-γ1, phospholipase C-γ1; PKC, protein kinase C.

GAP, GTPase-activating protein; GEF, guanine nucleotide exchange factor.

Real-time PCR analysis.

HeLa cells in 24-well plates were used for analysis of gene expression about 48 h after transfection with siRNAs. Cells were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and a TaqMan Gene Expression Cells-to-CT kit (Applied Biosystems) was used to prepare cell lysates and cDNA. When lysates were prepared, DNase was included in order to eliminate genomic DNA. In each experiment, a single sample of cells was used for each condition involving no siRNA, a control siRNA, or siRNAs targeting a particular human gene. Real-time PCR was performed in triplicate on each cDNA sample using an ABI 7500 or ABI 7900 instrument (Applied Biosystems). The TaqMan gene expression assay probes used for each of the 64 target genes in the human type IA PI 3-kinase pathway are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Each of these probes spans exon-exon junctions and should not detect genomic DNA. The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene (gene expression assay Hs99999905_m1; Applied Biosystems) was used as an endogenous control. Threshold cycle (CT) values for the 64 target genes ranged from 23 to 32 in the various experiments. CT values for the GAPDH endogenous controls were typically between 18 and 19. Data were analyzed by the comparative CT method (57), whereby CT values for target gene expression were normalized to those for GAPDH. Relative quantity (RQ) values were calculated as 2−ΔΔCT. To obtain the relative expression values shown in Fig. 2 to 4, the RQ values in a given experiment were normalized to the value in cells treated with nontargeting control siRNA 1 (NTC1). The relative expression values in Fig. 5 were obtained by normalization to RQ values in cells mock transfected in the absence of siRNA (“no-siRNA” condition). The data in Fig. 2 to 5 are means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) from 3 to 7 independent experiments, depending on the gene and siRNA condition.

For 10 of the 64 human genes analyzed, expression could not be reliably detected by using real-time PCR and the available probe (see Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). In these situations, the CT values obtained for the target genes ranged from 36 to undetectable. Control experiments with lysates that had not been subjected to reverse transcription yielded CT values from 36 to undetectable for the 64 genes. On the basis of these control experiments, any gene producing CT values of 36 or greater, by use of reverse-transcribed lysates, was considered to be expressed at levels too low for detection using the available probe. These genes either were not expressed in HeLa cells, were expressed at levels below the limit of detection of real-time PCR, or possibly were incapable of being detected because of a flaw in the probe design.

Bacterial entry assays.

HeLa cells were used for bacterial infections approximately 48 h after transfection with siRNA. Gentamicin protection assays to measure the entry of Listeria (see Fig. 2B, 3B, 4B, and 5) were performed by infecting cells for 1 h in the absence of gentamicin and then incubating them in DMEM with 20 μg/ml gentamicin for 2 h as described previously (24, 78). Entry experiments involving HeLa cells transfected with siRNA pools (Fig. 2 to 4) or single siRNAs (Fig. 5) were performed 3 to 7 times, depending on the target gene. The entry efficiency was first expressed as the percentage of the bacterial inoculum that survived gentamicin treatment. To obtain the relative entry values shown in Fig. 2 to 4, the absolute percentages in a given experiment were normalized to the values for cells treated with NTC1. The relative entry values in Fig. 5 were obtained by normalization to the percentages for cells mock transfected in the absence of siRNA (“no-siRNA” condition).

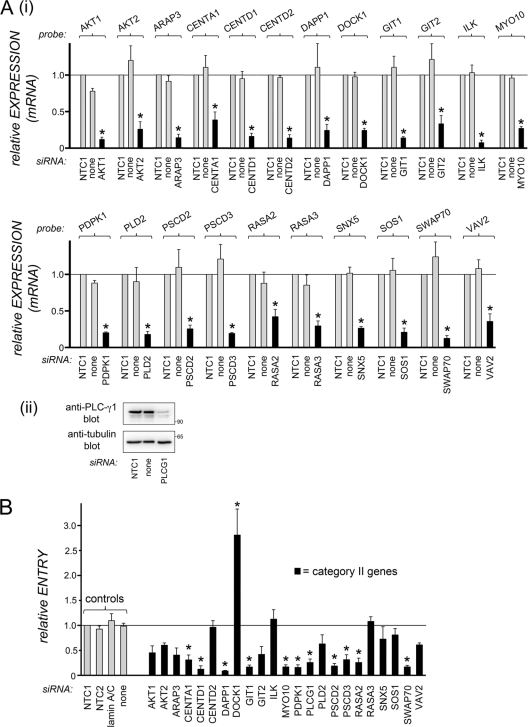

Fig 3.

Effects of siRNAs directed against category II host genes on human gene expression and internalization of Listeria. (A) Inhibition of host gene expression. HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA pools targeting the indicated category II host genes. Control transfection conditions and analysis of gene expression were carried out as described in the legend for Fig. 2. (i) Gene expression was analyzed by real-time PCR for all but one of the genes. (ii) In the case of PLCG1 (encoding PLC-γ1 protein), gene expression was assessed by Western blotting, since the probe did not detect expression (see Materials and Methods). Data are means ± SEM for 3 to 5 experiments, depending on the siRNA condition. Statistical analysis by ANOVA gave a P value of <0.0001. *, P < 0.05 relative to the NTC1 or no-siRNA control (by the Tukey-Kramer posttest). (B) Effects of siRNA pools on Listeria internalization. HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA pools directed against the indicated category II host gene. Control transfection conditions and measurement of bacterial entry were carried out as described in the legend for Fig. 2. Data for siRNAs targeting category II genes are means ± SEM for 3 to 5 experiments. Data obtained under the no-siRNA (none), NTC2, or lamin A/C siRNA control condition are from 46, 13, or 13 experiments, respectively. Statistical analysis by ANOVA gave a P value of <0.0001. *, P < 0.05 relative to the NTC1, NTC2, lamin A/C, or no-siRNA control (by the Tukey-Kramer posttest).

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation.

Approximately 48 h after transfection with siRNA, HeLa cells were solubilized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 0.05% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], and 10 mg/liter each of aprotinin and leupeptin). Western blotting and detection using ECL (enhanced chemiluminescence) or ECL Plus reagents (GE Healthcare) were performed as described previously (46, 78).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism (version 5.0a; GraphPad Software). For comparison of data from three or more conditions, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed. The Tukey-Kramer test was used as a posttest. A P value of 0.05 or lower was considered significant.

RESULTS

Construction of a siRNA library targeting components of the type IA PI 3-kinase pathway.

In order to better understand the mechanism of InlB-mediated internalization of Listeria, we used RNAi to target human genes encoding proteins that participate in type IA PI 3-kinase signaling. A literature search was performed to compile a list of 64 host genes whose products are involved in signal transduction mediated by type IA PI 3-kinase (Table 1). This list was then used to construct a short interfering RNA (siRNA) library, which was screened for effects on target host gene expression and Listeria entry. The human epithelial cell line HeLa was used for these studies, since this cell line is readily transfected and has been used extensively to study InlB-mediated entry (5, 24, 34, 85). When the list of genes to be targeted by RNAi was assembled, those encoding neuronal or lymphocyte-specific proteins unlikely to be expressed in HeLa cells were excluded.

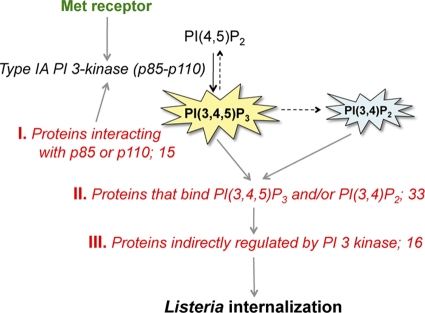

The human genes in the siRNA library were grouped into three categories, depending on the relationships of their protein products to type IA PI 3-kinase and its lipid products PI(3,4,5)P3 and/or PI(3,4)P2 (Table 1; Fig. 1). A brief description of the categories follows. Category I contained 15 genes encoding proteins that are known to interact physically with catalytic and/or regulatory subunits of type IA PI 3-kinase. Some of these proteins, namely, Ras GTPases, PI 3-kinase-interacting protein 1, and PTK2/FAK, control PI 3-kinase catalytic activity (12, 17, 97). These proteins therefore act upstream of PI 3-kinase. Other proteins, for example, Rab4 and Rab5 GTPases, have biochemical activities that are regulated by type IA PI 3-kinase (15). These proteins might act downstream of the lipid kinase. For the remaining category I genes, insufficient information was available to propose where their protein products might act with regard to PI 3-kinase. Of these proteins, APPL and Cbl function at least partly as adaptor proteins (43, 61, 83), and their roles might lie in connecting the PI 3-kinase pathway to other signaling pathways. Category II comprised 33 genes encoding proteins known to bind directly to PI(3,4,5)P3 and/or PI(3,4)P2. For most of these proteins, phosphoinositide binding is mediated by one or more pleckstrin homology (PH), Phox homology (PX), or DHR1 domains (54) (Table 1). A few category II gene products (e.g., GIT1, GIT2, SWAP70) bind PI(3,4,5)P3 through regions that are uncharacterized or that do not resemble other known protein-lipid interaction domains (79, 88). Category III was composed of 16 genes whose products are indirectly regulated by type IA PI 3-kinase (Table 1). The scope of category III genes was not meant to be exhaustive. Instead, we focused on genes encoding substrates or effectors of some well-characterized direct targets of PI 3-kinase. Examples include isoforms of protein kinase C (PKC) (53, 74), protein kinase N (substrates of the kinase PDK1) (64), or PAK kinases (substrates of PDK1) (30) and mTor (a kinase indirectly regulated by Akt proteins) (91).

Fig 1.

Human type IA PI 3-kinase pathway components targeted in the RNAi-based screen. During infection with Listeria, host type IA PI 3-kinase is activated downstream of the Met receptor and plays a critical role in bacterial internalization (45, 46, 78). Type IA PI 3-kinase uses PI(4,5)P2 as a substrate and produces the lipid second-messenger product PI(3,4,5)P3 (11, 31). PI(3,4)P2 is another second messenger, which is generated from PI(3,4,5)P3 by phosphatases (11). The RNAi-based screen performed in this study targeted three categories of host genes encoding proteins that act on the type IA PI 3-kinase signaling pathway. Category I genes encode proteins that interact with the 85-kDa regulatory and/or 110-kDa catalytic subunit of PI 3-kinase. Category II genes code for proteins that bind to the PI 3-kinase lipid products PI(3,4,5)P3 and/or PI(3,4)P2. Category III genes encode products that are indirectly controlled by type IA PI 3-kinase.

RNAi-based screen.

siRNAs that target the 64 genes encoding components of the type IA PI 3-kinase pathway were designed (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). For the vast majority of these genes (62 of 64), three different siRNAs were made and were combined into pools to test for effects on host target gene expression and Listeria entry. For the ILK gene, a pool of two siRNAs was used. The rationale for using a pooling approach was that screening of multiple siRNAs together might increase the probability of effectively silencing target gene expression in situations in which not all of the individual siRNAs are potent. For one of the host genes (HRAS), only one siRNA was used. This siRNA effectively inhibited gene expression (see below).

siRNA pools (or, for HRAS, a single siRNA) were transfected into HeLa cells. As controls, cells were mock transfected in the absence of siRNA or were transfected with a control “nontargeting” siRNA (referred to as NTC1) that has two or more mismatches with all known human mRNA transcripts. Approximately 48 h posttransfection, gene expression was assessed by real-time PCR (see Materials and Methods). Of the 64 genes selected for analysis, 47 displayed statistically significant reductions in gene expression (due to targeting siRNAs) relative to expression under control conditions (Fig. 2A, 3A, and 4A). For 10 of the 64 genes, expression could not be reliably detected by real-time PCR using the available probes (see Materials and Methods and Table S2 in the supplemental material). Effective antibodies against the product of one of these genes, PLC-γ1, were commercially available. Western blotting indicated depletion of PLC-γ1 protein (Fig. 3Aii). For eight of the genes targeted, expression was detected by real-time PCR, but siRNA pools targeting these genes did not reduce expression (see Table S2). In summary, of the 64 genes initially selected for silencing, 47 exhibited substantial RNAi-mediated reductions in expression at the mRNA or protein level. None of the siRNA conditions targeting these 47 genes affected cell growth or viability, as assessed by MTT assays (63) (data not shown).

The 47 genes whose expression was inhibited by siRNA were also examined for roles in Listeria entry. Internalization of Listeria into transfected HeLa cells was measured by gentamicin protection assays, in parallel with the gene expression studies (Fig. 2B, 3B, and 4B). Control conditions for the entry experiments included the absence of siRNAs and the presence of NTC1, used in the gene expression analyses. Additional controls were another nontargeting siRNA (NTC2) and a siRNA capable of silencing the nuclear protein lamin A/C. siRNAs against 21 of the type IA PI 3-kinase pathway genes resulted in statistically significant changes in Listeria entry from that with the controls (Fig. 2B, 3B, and 4B). For 19 of these genes, siRNAs reduced entry, suggesting a positive role in bacterial uptake. The extent of inhibition of entry ranged from ∼70 to 95%, depending on the host gene targeted. As a reference, under the same cell growth and control transfection conditions, a bacterial mutant in which the inlB gene is deleted enters HeLa cells at a frequency about 90% lower than that of the isogenic inlB-positive strain (34). For two of the human genes targeted in the RNAi screen (KRAS2 and DOCK1), siRNAs augmented the efficiency of internalization, consistent with a negative role. The 21 host genes implicated in bacterial entry encode 3 proteins that bind to catalytic or regulatory subunits of PI 3-kinase (Fig. 2), 12 proteins that interact with PI(3,4,5)P3 and/or PI(3,4)P2 (Fig. 3), and 6 proteins that are indirectly regulated by PI 3-kinase (Fig. 4). Collectively, the gene expression and bacterial entry results presented in Fig. 2 to 4 indicate that several members of the type IA PI 3-kinase pathway play important roles in InlB-mediated Listeria internalization. We comment below on known cellular functions of key host proteins that emerged from the RNAi screen (see Discussion). Also discussed are possible mechanisms by which some of the PI 3-kinase pathway proteins might promote Listeria entry.

Addressing possible off-target effects of siRNAs.

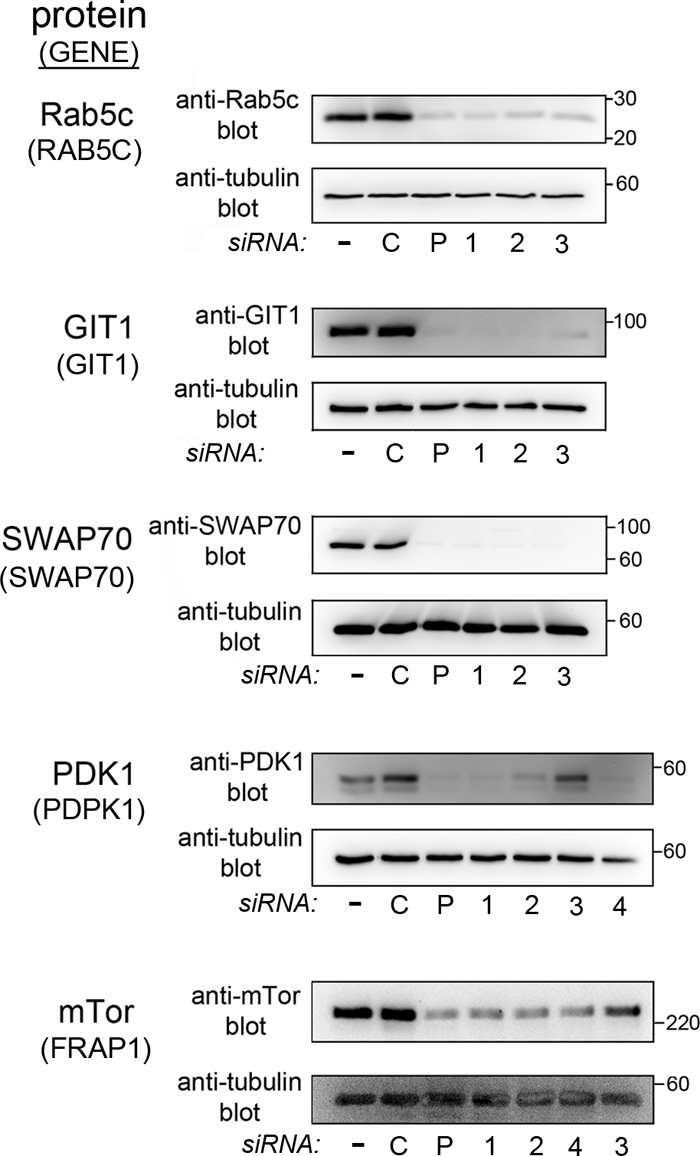

Although RNAi is a powerful method of genetic analysis, a potential weakness of this approach is the occurrence of “off-target” effects (22). The term “off target” refers to a situation in which a siRNA affects an mRNA other than the desired target mRNA. One common method of minimizing the possibility of off-target effects is to confirm that several different siRNA molecules recognizing distinct regions in a given mRNA cause the same biological phenotype (22). We selected 8 of the 21 human genes implicated in Listeria entry (Fig. 2 to 4) and tested whether multiple siRNAs inhibiting target gene expression also impaired bacterial uptake. The genes selected were the category I gene RAB5C, category II genes PSCD1, DAPP1, GIT1, PDPK1, and SWAP70, and category III genes FRAP1 and PRKCZ. The multiple siRNAs used consisted of the three individual components of the siRNA pools employed in the experiments for which results are shown in Fig. 2 to 4. In some cases (e.g., PDPK1 and FRAP1), a fourth siRNA was also tested. The data are presented in Fig. 5. Importantly, for each of the eight genes selected, three siRNAs with unique sequences inhibited both bacterial entry and gene expression at the mRNA level. For five of these eight human genes, effective antibodies were commercially available. We used these antibodies to confirm the inhibition of expression at the protein level (Fig. 6). Taken together, the findings in Fig. 5 and 6 indicate that off-target effects for the eight selected host genes are unlikely. The data support the idea that these genes have bona fide roles in Listeria internalization.

Fig 6.

Confirmation that siRNAs inhibit expression at the protein level. The human proteins evaluated for expression are given on the left, followed by the gene names in parentheses. HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA pools (P) or with individual siRNAs directed against the indicated human gene. As controls, cells either were mock transfected in the absence of siRNA (−) or were transfected with nontargeting control 1 siRNA (C). Approximately 48 h after transfection, cells were solubilized in RIPA buffer. The indicated target protein was detected by Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods. In order to confirm equivalent loading, membranes were then stripped and were probed a second time, with anti-tubulin antibodies.

In previous work, we confirmed that multiple siRNAs targeting the human CENTD1 gene (encoding the ARAP2 protein) impair gene expression at the mRNA and protein levels and also block Listeria entry (34). Based on the present study and previous work, we conclude that our RNAi-based screen has identified at least nine human genes that are required for efficient InlB-mediated entry of Listeria.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we describe an RNAi screen that led to the identification of at least nine human genes encoding proteins in the type IA PI 3-kinase pathway that play important roles in Listeria entry. One of the genes identified from the screen, RAB5C, codes for a protein that interacts with regulatory and catalytic subunits of type IA PI 3-kinase (15, 18, 52). Six of the host genes, CENTD1, PSCD2, DAPP1, GIT1, PDPK1, and SWAP70, encode proteins that bind directly to the PI 3-kinase lipid products PI(3,4,5)P3 and/or PI(3,4)P2 (3, 28, 79, 87, 88, 93). Two of the genes identified from the screen, FRAP1 and PRKCZ, code for proteins that are indirectly regulated by PI 3-kinase (3, 39, 75). In addition to the nine host genes described above, it seems likely that other members of the type IA PI 3-kinase signaling pathway are involved in the InlB-dependent entry of Listeria. The results obtained with siRNA pools implicated 21 different human genes in bacterial internalization (Fig. 2 to 5). Nine of these 21 genes were further examined for roles in Listeria entry by testing multiple individual siRNAs (Fig. 6). The results indicated that off-target effects were unlikely and that the nine host genes therefore play important roles in bacterial uptake. Future work using single siRNAs will determine which of the remaining 12 host genes have bona fide functions in Listeria entry.

For 26 of the host genes targeted in our study, siRNA-mediated inhibition of expression failed to affect Listeria entry in a statistically significant fashion. These findings suggest that many of these 26 genes do not play important roles in bacterial internalization, at least not under the conditions employed in our work. It is worth noting that 2 of these 26 human genes, PLD2 and CBL, have been implicated in InlB-mediated uptake previously. In the case of PLD2, an earlier study used a cell line other than HeLa (37). The apparent discrepancy between our data and the prior study is most likely due to cell line differences. Previous siRNA studies targeting CBL in HeLa cells suggested that this host gene is needed for efficient Listeria entry (85). In our work, siRNAs directed against CBL reduced Listeria internalization by approximately 70%, but the effect was not statistically significant.

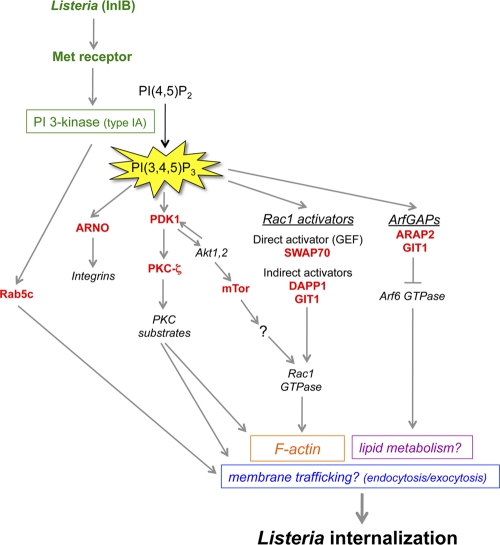

As described above, our RNAi screen identified at least nine human genes that have important functions in InlB-mediated entry. How might these genes control the internalization of Listeria? Below, we describe what is known about the cellular functions of the protein products of the genes. The molecular mechanisms by which these proteins might regulate bacterial entry are also discussed and are summarized in Fig. 7.

Fig 7.

Potential mechanisms of control of Listeria entry by the type IA PI 3-kinase signaling pathway. Infection of human cells with Listeria expressing InlB results in activation of the host Met receptor and of type IA PI 3-kinase (24, 45, 46, 78). The RNAi-based screen described in this work led to the identification of nine human proteins involved in PI 3-kinase signaling that play important roles in Listeria entry. Based on the biological functions of these nine proteins reported in the scientific literature, a diagram was constructed depicting some of the possible ways in which the host proteins could participate in bacterial uptake. Rab5c, a protein that interacts with regulatory and catalytic subunits of type IA PI 3-kinase, could promote Listeria entry by controlling the host endocytic machinery (14, 85). ARNO, an activator of Arf GTPases that binds directly to the PI 3-kinase product PI(3,4,5)P3, might help maintain proper levels of integrins, a class of receptor recently found to enhance InlB-mediated entry, in the plasma membrane (2). The serine/threonine kinase PKC-ζ could promote Listeria internalization by controlling the actin cytoskeleton and/or the delivery of membrane through exocytosis (7, 53, 73). PKC-ζ is indirectly regulated by PI 3-kinase through the master kinase PDK1, which is a direct target of PI(3,4,5)P3 (3). mTor, a serine/threonine kinase indirectly controlled by type IA PI 3-kinase, might promote bacterial uptake through activation of the host proteins Rac1 and/or PKC-α (not shown) (75, 91). Apart from mTor, three other human proteins identified in the RNAi screen have the potential to control Listeria entry though activation of Rac1 GTPase. These proteins, SWAP70, DAPP1, and GIT1, each bind directly to PI(3,4,5)P3. SWAP70 is a direct activator of Rac1 and stimulates nucleotide exchange on the GTPase (79). DAPP1 and GIT1 lack recognizable guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) domains and likely activate Rac1 indirectly. In addition to being an indirect activator of Rac1, GIT1 is also a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) that inhibits Arf6 GTPase (41). Along with ARAP2, another Arf6 GAP needed for Listeria entry (34), GIT1 might restrain the activation of Arf6, which would otherwise interfere with bacterial uptake. Constitutively activated Arf6 alleles inhibit Listeria internalization (34) and also induce the redistribution of cholesterol from the plasma membrane to internal membrane compartments (65). Since plasma membrane cholesterol is critical for InlB-mediated entry, it is possible that GIT1 and/or ARAP2 promotes Listeria uptake by maintaining proper localization of cholesterol and/or other lipids (34).

Rab5c.

Rab5c is one of three Rab5 GTPases that control clathrin-dependent endocytosis and early endosome fusion (14). Results from the RNAi-based screen indicated a role for Rab5c, but not for the Rab5a or Rab5b protein, in Listeria entry (Fig. 2, 5, and 6). Activated Rab5 proteins bind to the p110 catalytic and p85 regulatory subunits of type IA PI 3-kinase (15, 18, 52). The interaction of Rab5 proteins with p85 results in enhanced GTP hydrolysis on Rab5 (15). These findings suggest that PI 3-kinase might control Rab5-mediated endocytosis and/or subsequent vesicular trafficking. Importantly, the InlB-dependent entry of Listeria requires clathrin and several other human proteins that regulate clathrin-mediated endocytosis (85). It is possible that Rab5c works together with the endocytic machinery previously reported to control Listeria uptake. How might Rab5-dependent endocytosis promote bacterial entry? Recent results indicate an important role for Rab5 in signal transduction and actin polymerization mediated by the Met receptor (68). Activation of Met by its mammalian ligand hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) leads to the Rab5-dependent stimulation of the GTPase Rac1 and subsequent actin polymerization. Rab5 promotes the internalization of Rac1 into endosomes, where Rac1 is then activated. Activated, endosomal Rac1 is then delivered to specific sites on the plasma membrane, resulting in cortical actin polymerization. Importantly, Rac1 is needed for the InlB-mediated internalization of Listeria (4). The recent findings with Rab5 and Met raise the possibility that one role of Rab5c in Listeria entry might be to facilitate the localized delivery of Rac1 to promote subsequent cytoskeletal remodeling.

Regulators of Arf GTPases (ARAP2, GIT1, ARNO).

The results from the RNAi-based screen indicated that at least six host genes encoding proteins that bind PI(3,4,5)P3 have important functions in Listeria internalization. Three of these host proteins, ARAP2 (encoded by CENTD1), GIT1, and ARNO (encoded by PSCD2), are regulators of small GTPases of the Arf family (26). ARAP2 and GIT1 are GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) capable of antagonizing various Arf GTPases (26). Binding of PI(3,4,5)P3 to ARAP2 or GIT1 enhances the GAP activities of these proteins (88, 93). These findings indicate that type IA PI 3-kinase can inhibit Arf GTPases through ARAP2 and GIT1. In previous work, we found that ARAP2 promotes Listeria entry, in part by restraining the activity of Arf6 (34). The mechanism by which ARAP2-mediated inhibition of Arf6 facilitates bacterial uptake is not known. The observation that uncontrolled activation of Arf6 leads to the sequestration of cholesterol and PI(4,5)P2 in internal membranes (9, 65) prompted a hypothesis that ARAP2 might maintain the normal plasma membrane localization of lipids critical for Listeria uptake (34). It is possible that GIT1, like ARAP2, promotes Listeria internalization by antagonizing Arf6. This idea would imply that neither ARAP2 nor GIT1 alone is sufficient to fully inactivate Arf6. Alternatively, GIT1 could act through regulation of other Arf GTPases, such as Arf1, Arf2, Arf3, or Arf5 (41, 88). A third way in which GIT1 could mediate Listeria uptake is by contributing to the activation of Rac1 and/or Cdc42 GTPases. Both Rac and Cdc42 are needed for InlB-mediated entry (4, 5). GIT1 promotes the activation of these two GTPases by binding to the guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) β-PIX (41, 47). ARNO, the third Arf regulator identified in our RNAi screen, is a GEF that activates Arf1 or Arf6 GTPases (26). PI(3,4,5)P3 binds to a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain in ARNO, thereby recruiting this GEF to the plasma membrane (26, 87). In previous work, we found that siRNA-mediated depletion of Arf6 did not impair Listeria entry (34). This finding indicates that ARNO does not mediate bacterial internalization through Arf6. It is possible that ARNO acts on Arf1 to stimulate Listeria uptake. Experiments involving RNAi-mediated depletion of Arf1 indicate an important role for this GTPase in InlB-mediated bacterial entry (P. Le and K. Ireton, unpublished data). Arf1 could control entry by promoting PI(4,5)P2 synthesis through PI 4-phosphate 5-kinase (26). Alternatively or additionally, ARNO might stimulate Listeria uptake by promoting the recycling of integrin receptors to the plasma membrane (66). Integrins contribute to signaling downstream of the Met receptor (82) and are also needed for efficient InlB-mediated Listeria entry (2).

SWAP70.

Another PI(3,4,5)P3-interacting protein that is required for Listeria entry is SWAP70, a known direct activator of Rac1 GTPase (79). As previously mentioned, Rac1 promotes InlB-mediated entry by eliciting actin cytoskeletal changes through the Arp2/3 complex (4, 5). SWAP70 is a Rac1 GEF whose activity is stimulated by PI(3,4,5)P3 (79). Our findings suggest that Rac1 activation downstream of the Met receptor during Listeria entry might be promoted by SWAP70. Apart from SWAP70, our RNAi-based screen targeted several other PI(3,4,5)P3-regulated GEFs for Rac1. The results indicated that the GEFs Dock180, SOS1, and Vav2 are dispensable for Listeria internalization (Fig. 3).

DAPP1.

The DAPP1 gene is critical for Listeria entry and encodes a PI(3,4,5)P3-binding adaptor protein. DAPP1 protein contains a PH domain that interacts with PI(3,4,5)P3, an SH2 domain, and a tyrosine residue capable of being phosphorylated (1, 28). Known functions of DAPP1 include regulation of phospholipase C-γ and activation of Rac1 GTPase (1, 95). The lack of a recognizable GEF domain in DAPP1 indicates that the effect on Rac1 activity is likely indirect. Our RNAi data suggested an important role for phospholipase C-γ1 in InlB-mediated entry (Fig. 3). Possible ways in which DAPP1 could promote Listeria uptake include activation of PLC-γ1 and/or Rac1.

PDK1 and PKC-ζ.

The results from the RNAi screen indicated important functions for the serine/threonine kinase PDK1 (encoded by the PDPK1 gene) in Listeria entry. PDK1 is a “master kinase” that phosphorylates the activation loop of more than 20 serine/threonine kinases of the AGC family (3, 74). PDK1-mediated phosphorylation is critical for the activity of these AGC kinases. Our siRNA library targeted 13 genes encoding AGC kinases that are PDK1 substrates (Table 1). Eight of these 13 genes were expressed in HeLa cells and were effectively silenced by siRNA (Fig. 4; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). These eight genes were AKT1, AKT2, PRKCD (encoding PKC-δ), PRKCG (encoding PKC-γ), PRKCZ (encoding PKC-ζ), PKN1, PKN2, and SGK1. The results with siRNA pools suggested that PRKCD, PRKCZ, PKN1, and PKN2 might have important functions in Listeria internalization. Experiments with single siRNAs confirmed that PRKCZ plays a crucial role in InlB-mediated entry. Importantly, the product of PRKCZ, PKC-ζ, is known to regulate the actin cytoskeleton (35, 39, 56). Potential substrates of PKC-ζ include proteins that cross-link F-actin to the plasma membrane (MARCKS and ERM proteins), actin binding proteins of the coronin family, the actin-capping protein adducin, the actin-bundling protein fascin, and the anti-capping protein VASP (16, 53). PKC-ζ could mediate Listeria entry, at least in part, by stimulating actin remodeling through phosphorylation of one or more of these substrates. Another important activity of PKC-ζ is the promotion of exocytosis—the fusion of intracellular vesicles with the plasma membrane (56, 73). Specifically, PKC-ζ phosphorylates VAMP2, a vesicular protein that mediates vesicle docking to the plasma membrane (7). Thus far, no role for exocytosis in Listeria entry has been described. During Fc-γ receptor-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages, exocytic delivery of vesicles to the phagosome replenishes the plasma membrane that would otherwise be lost due to particle internalization (8). It is possible that exocytosis occurs during Listeria uptake and serves a similar function. Another potential function for exocytosis could be to provide the plasma membrane needed for the extension of pseudopods around adherent bacteria.

mTor.

The RNAi screen revealed a critical role for the host protein mTor in InlB-mediated Listeria entry. mTor (encoded by the FRAP1 gene) is a serine/threonine kinase that functions downstream of type IA PI 3-kinase to regulate several biological processes, including translation, ribosome biogenesis, autophagy, and cytoskeletal organization (75, 91). mTor is present in two different multiprotein complexes, termed mTORC1 and mTORC2. mTORC1 controls protein synthesis, cell growth, and autophagy. In contrast, mTORC2 regulates the actin cytoskeleton. Many of the cellular functions of mTORC1 are inhibited by the drug rapamycin (75), whereas mTORC2 is thought to be insensitive to this compound. Interestingly, treatment of HeLa cells with rapamycin fails to impair InlB-mediated Listeria internalization (data not shown), suggesting that the mTor complex involved in bacterial uptake is likely mTORC2, not mTORC1. mTORC2 is known to control the actin cytoskeleton through phosphorylation of PKC-α or activation of Rac1 GTPase (91). Future work will determine whether mTor promotes Listeria internalization through PKC-α or Rac1, or via a previously unrecognized pathway.

The RNAi-based screen described in this work represents a key first step toward understanding how type IA PI 3-kinase promotes InlB-mediated Listeria entry. Future studies will examine the molecular mechanisms by which the proteins encoded by the various host genes identified in the screen control Listeria uptake. Such work will contribute to a better understanding of how bacterial activation of the Met receptor elicits actin cytoskeletal changes that drive Listeria internalization. Future studies of human proteins identified from the screen also have the potential to uncover novel host cell events needed for bacterial entry, such as localized exocytosis (Fig. 7).

Importantly, human type IA PI 3-kinase plays a critical role in the internalization of several microbial pathogens other than Listeria. Such microbes include bacterial pathogens that cause anthrax (Bacillus anthracis) (67), respiratory infections (Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Chlamydia pneumoniae) (19, 48), and food-borne disease (Campylobacter jejuni and Yersinia enterocolitica) (42, 77). Host type IA PI 3-kinase also promotes the entry of the virus responsible for hemorrhagic fever (Ebola virus) (76) and parasites causing Chagas' disease (Trypanosoma cruzi) (81) or toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma gondii) (23). To the best of our knowledge, our work is the first systematic study to identify components of the host type IA PI-3 kinase pathway involved in infection by a microbial pathogen. Human proteins identified as critical for Listeria entry may also be viable candidates for host factors mediating infection by these other important pathogens.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rob Davey for suggestions on the RNAi screen design. John Brumell, Scott Gray-Owen, and Ashu Sharma are thanked for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by an “in-house” grant from the University of Central Florida, a University of Otago research grant (UORG), and grants from the National Institutes of Health (1R01AI085072-01A1) and the Marsden Fund (10-UOO-015), all awarded to K.I.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 12 December 2011

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Allam A, Niiro H, Clark EA, Marshall AJ. 2004. The adaptor protein Bam32 regulates Rac1 activation and actin remodeling through a phosphorylation-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 279:39775–39782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Auriemma C, et al. 2010. Integrin receptors play a role in the internalin B-dependent entry of Listeria monocytogenes into host cells. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 15:496–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bayascas JR. 2010. PDK1: the major transducer of PI 3-kinase actions. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 346:9–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bierne H, et al. 2001. A role for cofilin and LIM kinase in Listeria-induced phagocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 155:101–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bierne H, et al. 2005. WASP-related proteins, Abi and Ena/VASP are required for Listeria invasion induced by the Met receptor. J. Cell Sci. 118:1537–1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bonazzi M, Lecuit M, Cossart P. 2009. Listeria monocytogenes internalin and E-cadherin: from structure to pathogenesis. Cell. Microbiol. 11:693–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Braiman L, et al. 2001. Activation of protein kinase Cζ induces serine phosphorylation of VAMP2 in the GLUT4 compartment and increases glucose transport in skeletal muscle. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:7852–7861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Braun V, Niedergang F. 2006. Linking exocytosis and endocytosis during phagocytosis. Biol. Cell 98:195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brown FD, Rozelle AL, Yin HL, Balla R, Donaldson JG. 2001. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and Arf6-regulated membrane traffic. J. Cell Biol. 154:1007–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bruhn MA, Pearson RB, Hannan RD, Sheppard KE. 2010. Second Akt: the rise of SGK in cancer signalling. Growth Factors 28:394–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bunney TD, Katan M. 2010. Phosphoinositide signalling in cancer: beyond PI3K and PTEN. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10:342–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Castellano E, Downward J. 2011. Ras interaction with PI3K: more than just another effector pathway. Genes Cancer 2:261–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ceccarelli DFJ, et al. 2007. Non-canonical interaction of phosphoinositides with pleckstrin homology domains of Tiam1 and ARHGAP9. J. Biol. Chem. 282:13864–13874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ceresa BP. 2006. Regulation of EGFR endocytic trafficking by rab proteins. Histol. Histopathol. 21:987–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chamberlain MD, Berry TR, Pastor MC, Anderson DH. 2004. The p85a subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase binds to and stimulates the GTPase activity of Rab proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 279:48607–48614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chan KT, Creed SJ, Bear JE. 2011. Unraveling the enigma: progress towards understanding the coronin family of actin regulators. Trends Cell Biol. 21:481–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen HC, Appenddu PA, Isoda H, Guan JL. 1996. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 397 in focal adhesion kinase is required for binding phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271:26329–26334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Christoforidis S, et al. 1999. Phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinases are Rab5 effectors. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:249–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Coombes BK, Mahony JB. 2002. Identification of MEK- and phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent signalling as essential events during Chlamydia pneumoniae invasion of HEp2 cells. Cell. Microbiol. 4:447–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cote JF, Motoyama AB, Bush JA, Vuori K. 2005. A novel and evolutionarily conserved PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-binding domain is necessary for Dock180 signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 7:797–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cox D, et al. 2002. Myosin X is a downstream effector of PI(3)K during phagocytosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:469–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cullen BR. 2006. Enhancing and confirming the specificity of RNAi experiments. Nat. Methods 3:677–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. da Silva VC, da Silva EA, Cruz MC, Charvier P, Mortara RA. 2009. Arf6, PI 3-kinase and host cell actin cytoskeleton in Toxoplasma gondii cell invasion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 378:656–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dokainish H, Gavicherla B, Shen Y, Ireton K. 2007. The carboxyl-terminal SH3 domain of the mammalian adaptor CrkII promotes internalization of Listeria monocytogenes through activation of host phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Cell. Microbiol. 9:2497–2516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Donald S, et al. 2004. P-Rex2, a new guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rac. FEBS Lett. 572:172–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Donaldson JG, Jackson CL. 2011. ARF family G proteins and their regulators: roles in membrane transport, development, and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12:362–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dowler S, et al. 2000. Identification of pleckstrin-homology domain containing proteins with novel phosphoinositide-binding specificities. Biochem. J. 351:19–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dowler S, Currie RA, Downes CP, Alessi DR. 1999. DAPP1: a dual adaptor for phosphotyrosine and 3-phosphoinositides. Biochem. J. 342:7–12 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dramsi S, et al. 1995. Entry of Listeria monocytogenes into hepatocytes requires expression of InlB, a surface protein of the internalin multigene family. Mol. Microbiol. 16:251–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dummler B, Ohshiro K, Kumar R, Field J. 2009. Pak protein kinases and their role in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 28:51–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC. 2006. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat. Rev. Genet. 7:606–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Falasca M, et al. 1998. Activation of phospholipase Cγ by PI 3-kinase-induced PH domain-mediated membrane targeting. EMBO J. 15:414–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Foster KG, Fingar DC. 2010. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTor): conducting the cellular signaling symphony. J. Biol. Chem. 285:14071–14077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gavicherla B, et al. 2010. Critical role for the host GTPase-activating protein ARAP2 in InlB-mediated entry of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun. 78:4532–4541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gomez J, et al. 1995. Physical association and functional relationship between protein kinase Cζ and the actin cytoskeleton. Eur. J. Immunol. 25:2673–2678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Han J, et al. 1998. Role of substrates and products of PI 3-kinase in regulating activation of Rac-related guanosine triphosphatases by Vav. Science 279:558–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Han X, et al. 2011. InlB-mediated Listeria monocyotogenes internalization requires a balanced phospholipase D activity maintained through phospho-cofilin. Mol. Microbiol. 81:860–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hannigan GE, Coles JG, Dedhar S. 2007. Integrin-linked kinase at the heart of cardiac contractility, repair, and disease. Circ. Res. 100:1408–1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hirai T, Chida K. 2003. Protein kinase Cζ (PKCζ): activation mechanisms and cellular functions. J. Biochem. 133:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hirsch E, Braccini L, Ciraolo E, Morello F, Perino A. 2009. Twice upon a time: PI3K's secret double life exposed. Trends Biochem. Sci. 34:244–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hoefen RJ, Berk BC. 2006. The multifunctional GIT family of proteins. J. Cell Sci. 119:1469–1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hu L, McDaniel JP, Kopecko DJ. 2006. Signal transduction events involved in human epithelial cell invasion by Campylobacter jejuni 81-176. Microb. Pathog. 40:91–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hunter S, Burton EA, Wu SC, Anderson SM. 1999. Fyn associates with Cbl and phosphorylates tyrosine 731 in Cbl, a binding site for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:2097–2106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ireton K. 2007. Entry of the bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes into mammalian cells. Cell. Microbiol. 9:1365–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ireton K, et al. 1996. A role for phosphoinositide 3-kinase in bacterial invasion. Science 274:780–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ireton K, Payrastre B, Cossart P. 1999. The Listeria monocytogenes protein InlB is an agonist of mammalian phosphoinositide-3-kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:17025–17032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jones NP, Katan M. 2007. Role of phospholipase C γ1 in cell spreading requires association with a β-PIX/GIT1-containing complex, leading to activation of Cdc42 and Rac1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:5790–5805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kierbel A, Gassama-Diagne A, Mostov K, Engel JN. 2005. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-protein kinase B/Akt pathway is critical for Pseudomonas aeuruginosa strain PAK internalization. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:2577–2585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kim D, Chung J. 2002. Akt: versatile mediator of cell survival and beyond. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 35:106–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Klarlund J, et al. 1997. Signaling by phosphoinositide 3,4,5-trisphosphate through proteins containing pleckstrin and Sec7 domains. Science 275:1927–1930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Krugmann S, et al. 2002. Identification of ARAP3, a novel PI3K effector regulating both Arf and Rho GTPases, by selective capture on phosphoinositide affinity matrices. Mol. Cell 9:95–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kurosu H, Katada T. 2001. Association of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase composed of p110β-catalytic and p85-regulatory subunits with the small GTPase Rab5. J. Biochem. 130:73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Larsson C. 2006. Protein kinase C and the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. Cell. Signal. 18:276–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lemmon MA. 2003. Phosphoinositide recognition domains. Traffic 4:201–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lietzke SE, et al. 2000. Structural basis of 3-phosphoinositide recognition by pleckstrin homology domains. Mol. Cell 6:385–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Liu LZ, et al. 2006. Protein kinase zeta mediates insulin-induced glucose transport through actin remodeling in L6 muscle cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 17:2322–2330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Manning BD, Cantley LC. 2007. Akt/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell 129:1261–1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mengaud J, Ohayon H, Gounon P, Mege RM, Cossart P. 1996. E-cadherin is the receptor for internalin, a surface protein required for entry of L. monocytogenes into epithelial cells. Cell 84:923–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Merino-Trigo A, et al. 2004. Sorting nexin 5 is localized to a subdomain of the early endosomes and is recruited to the plasma membrane following EGF stimulation. J. Cell Sci. 117:6413–6424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mitsuuchi Y, et al. 1999. Identification of a chromosome 3p14.3-21.1 gene, APPL, encoding an adaptor molecule that interacts with the oncoprotein-serine/threonine kinase Akt2. Oncogene 18:4891–4898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Miura K, et al. 2002. ARAP1: a point of convergence for Arf and Rho signaling. Mol. Cell 9:109–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mosmann T. 1983. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 65:55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mukai H. 2003. The structure and function of PKN, a protein kinase having a catalytic domain homologous to that of PKC. J. Biochem. 133:17–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Naslavsky N, Weigert R, Donaldson JG. 2004. Convergence of non-clathrin- and clathrin-derived endosomes involves Arf6 inactivation and changes in phosphoinositides. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:3542–3552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Oh SJ, Santy LC. 2010. Differential effects of cytohesins 2 and 3 on β1 integrin recycling. J. Biol. Chem. 285:14610–14616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Oliva C, Turnbaugh CL, Kearney JF. 2009. CD14-Mac-1 interactions in Bacillus anthracis spore internalization by macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:13957–13962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Palamidessi A, et al. 2008. Endocytic trafficking of Rac is required for the spatial restriction of signaling in cell migration. Cell 134:135–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Plantard L, et al. 2010. PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is a regulator of myosin-X localization and filopodia formation. J. Cell Sci. 123:3525–3534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Posfay-Barbe KM, Wald ER. 2009. Listeriosis. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 14:228–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Powner DJ, Wakelam MJO. 2002. The regulation of phospholipase D by inositol phospholipids and small GTPases. FEBS Lett. 531:62–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Rameh LE, et al. 1997. A comparative analysis of the phosphoinositide binding specificity of pleckstrin homology domains. J. Biol. Chem. 272:22059–22066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Rosse C, et al. 2009. An aPKC-exocyst complex controls paxillin phosphorylation and migration through localised JNK activation. PLoS Biol. 7:e1000235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rosse C, et al. 2010. PKC and the control of localized signal dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11:103–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Russell RC, Fang C, Guan KL. 2011. An emerging role for Tor signaling in mammalian tissue and stem cell physiology. Development 138:3343–3356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Saeed MF, Kolokoltsov AA, Freiberg AN, Holbrook MR, Davey RA. 2008. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt pathway controls cellular entry of Ebola virus. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Schulte R, Zumbihl R, Kampik D, Fauconnier A, Autenrieth IB. 1998. Wortmannin blocks Yersinia invasin-triggered internalization, but not interleukin-8 production by epithelial cells. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 187:53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Shen Y, Naujokas M, Park M, Ireton K. 2000. InlB-dependent internalization of Listeria is mediated by the Met receptor tyrosine kinase. Cell 103:501–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Shinohara M, et al. 2002. SWAP-70 is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor that mediates signalling of membrane ruffling. Nature 416:759–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Smith CIE, et al. 2001. The Tec family of cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases: mammalian Btk, Bmx, Itk, Tec, Txk and homologs in other species. Bioessays 23:436–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Todorov AG, Einicker-Lamas M, Castro SL, Oliveira MM, Giulherme A. 2000. Activation of host phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases by Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J. Biol. Chem. 275:32182–32186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Trusolino L, Bertotti A, Comoglio PM. 2010. Met signaling: principles and functions in development, organ regeneration, and cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11:834–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ueno H, et al. 1998. c-Cbl is tyrosine-phosphorylated by interleukin-4 and enhances mitogenic and survival signals of interleukin-4 receptor by linking with the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. Blood 91:46–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Vazquez-Boland JA, et al. 2001. Listeria pathogenesis and molecular virulence determinants. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:584–640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Veiga E, Cossart P. 2005. Listeria hijacks the clathrin-dependent endocytic machinery to invade mammalian cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 7:894–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Venkateswarlu K, Cullen PJ. 1999. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a human homologue of centaurin-α. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 262:237–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Venkateswarlu K, Oatey PB, Tavare JM, Cullen PJ. 1998. Insulin-dependent translocation of ARNO to the plasma membrane of adipocytes requires phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Curr. Biol. 8:463–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Vitale N, et al. 2000. GIT proteins, a novel family of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-tris phosphate-stimulated GTPase-activating proteins for Arf6. J. Biol. Chem. 275:13901–13906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Wollert T, et al. 2007. Extending the host range of Listeria monocytogenes by rational protein design. Cell 129:891–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Woodfield RJ, et al. 2001. The p85 subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase is associated with beta-catenin in the cadherin-based adhesion complex. Biochem. J. 360:335–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. 2006. Tor signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124:471–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Yarwood S, Bouyoucef-Cherchalli D, Cullen PJ, Kupzig S. 2006. The GAP1 family of GTPase-activating proteins: spatial and temporal regulators of small GTPase signalling. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34:846–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Yoon HY, et al. 2006. ARAP2 effects on the actin cytoskeleton are dependent on Arf6-specific GTPase-activating-protein activity and binding to RhoA-GTP. J. Cell Sci. 119:4650–4666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Yoshii S, et al. 1999. Alpha-PIX nucleotide exchange factor is activated by interaction with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Oncogene 18:5680–5690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Zhang TT, et al. 2009. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase-regulated adapters in lymphocyte activation. Immunol. Rev. 232:255–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Zhong Q, et al. 2002. Endosomal localization and function of sorting nexin 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:6767–6772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Zhu Z, et al. 2007. PI3K is negatively regulated by PIK3IP1, a novel p110 interacting protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 358:66–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.