Fifty-two species-associated amino acid residues were found between human and avian influenza viruses.

Keywords: human influenza, avian influenza, host specificity, genome, sequence analysis, research

Abstract

Position-specific entropy profiles created from scanning 306 human and 95 avian influenza A viral genomes showed that 228 of 4,591 amino acid residues yielded significant differences between these 2 viruses. We subsequently used 15,785 protein sequences from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) to assess the robustness of these signatures and obtained 52 "species-associated" positions. Specific mutations on those points may enable an avian influenza virus to become a human virus. Many of these signatures are found in NP, PA, and PB2 genes (viral ribonucleoproteins [RNPs]) and are mostly located in the functional domains related to RNP-RNP interactions that are important for viral replication. Upon inspecting 21 human-isolated avian influenza viral genomes from NCBI, we found 19 that exhibited >1 species-associated residue changes; 7 of them contained >2 substitutions. Histograms based on pairwise sequence comparison showed that NP disjointed most between human and avian influenza viruses, followed by PA and PB2.

Pandemic influenza A virus infections have occurred 3 times during the past century; the 1957 (H2N2) and 1968 (H3N2) pandemic strains emerged from a reassortment of human and avian viruses (1). Recently, all 8 genome segments from the 1918 (H1N1) influenza A virus were completely sequenced. The results indicate that the 1918 pandemic virus may not have emerged by a reassortment of avian and human virus as did the 2 other pandemic strains. Although the 1918 H1N1 is not considered an avian virus, it is the most avianlike of all mammalian influenza viruses (2,3). The recent circulation of highly pathogenic avian H5N1 viruses in Asia from 2003 to 2006 has caused >90 human deaths and has raised concern about a new pandemic (4). Therefore, we need to understand what genetic variations could render avian influenza virus capable of becoming a pandemic strain. Genomewide comparison of human versus avian influenza A viruses would show the evolutionary similarities and differences between them and thus provide information for studying the mechanism of influenza viral infection and replication in different host species.

Although many research efforts have focused on the molecular evolution of specific genes of influenza viruses, comprehensive comparisons among the nucleotide sequences of all 8 genomic segments and among the 11 encoded protein sequences have not been extensively reported. In this study, we used several computational approaches for finding specific genetic signatures characteristic of human and avian influenza A viral genomes. We subsequently validated the robustness of those signatures with human and avian protein sequences downloaded from Influenza Virus Resources at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/FLU/FLU.html).

Materials and Methods

Clinical Isolates

Throat swabs from patients with influenzalike syndromes were collected from the Clinical Virology Laboratory, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. The specimens were inoculated in MDCK cells. Typing for influenza A virus was then performed with immunofluorescent assay by type-specific monoclonal antibody (Dako, Cambridgeshire, UK). Subtyping was conducted by reverse transcription (RT)–PCR with subtype-specific primers.

Sequence Analysis

The RT-PCR product was purified by using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The nucleotide sequence was determined with an automated DNA sequencer. Sequence editing and processing were performed with Lasergene, version 3.18 (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA). Multiple sequence alignment was performed with ClustalW version 1.83 (ftp://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/software/unix/clustalw). Global sequence comparison that yielded pairwise sequence identities used in histogram analysis was done with the program Needle in the EMBOSS package (5). Amino acid sequences were translated from coding sequences and aligned by BioEdit (6). An entropy value was defined at an aligned amino acid position according to the formula ΣPi*log(Pi), in which i is the observed probability for each of the 20 amino acids (aa) (7). A graphic tool was developed in Java for displaying the entropy plot used in this work. All amino acid numberings are based on influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (PR8).

Sequences Used in Study

To show the host-associated amino acid signatures, we retrieved full genome sequences (as of August 22, 2005) from the genome browser at Influenza Sequence Database (ISD) (8). To differentiate between avian and human influenza viruses, we excluded human-isolated avian influenza viruses from the human dataset and examined those sequences separately. Altogether, we had 95 avian and 306 human influenza viral genomes, henceforth termed "primary dataset." All 11 viral proteins encoded by the 8 genomic RNA segments were compared: PB2, PB1, PB1-F2, PA, HA, NP, NA, M1, M2, NS1, and NS2.

Avian influenza viruses from human influenza patients were separately retrieved from NCBI as well as from ISD. Altogether, we had 417 protein sequences from 60 avian influenza strains, in which 21 strains contain sequences (full or nearly full length) from all 8 genomic RNA segments.

For validating the signatures obtained from analyzing the primary dataset, we further retrieved 15,785 human or avian influenza A viral protein sequences from NCBI's Influenza Virus Resources. Details for the sequences used can be found in Appendix, Supporting Materials and Methods, as well as in Table A1 and Table A2. Eleven Taiwanese genomes produced in this work have been deposited in GenBank with accession numbers DQ415283 through DQ415370.

Results

Differing Amino Acid Residues

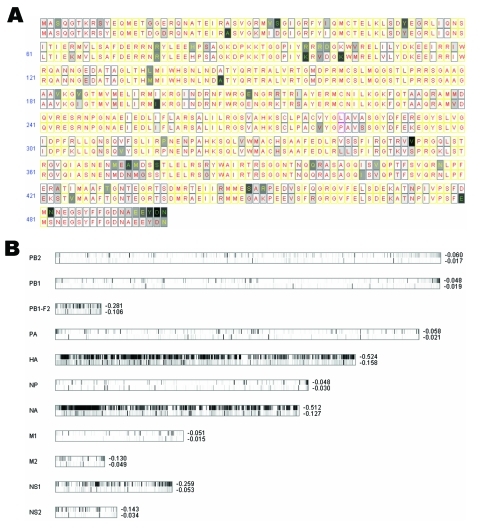

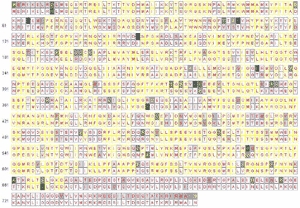

Using previously described methods (7), we separately calculated an entropy value for every aligned amino acid position for 95 avian influenza viruses and 306 human influenza viruses. Those amino acid residues with an entropy value between 0 and –0.4 for both the human and avian strains were identified as most highly conserved. We chose this entropy threshold on the basis of the entropy value –0.379, calculated at position 627 of PB2 for the 95 avian viruses. This widely reported, species-associated residue is highly conserved; it has E (Glu) in 83 and K (Lys) in 12 avian isolates and Lys in all 306 human isolates. We then selected those conserved positions with distinct amino acid residues between human and avian influenza viruses as potential host-associated signatures. An entropy plot for identifying such signature residues for avian versus human influenza virus NP segments is shown in Figure panel A. In each aligned position, we placed an avian consensus residue on top and a human consensus at the bottom. For example, the entropy value is zero at amino acid position 283 for both avian and human strains, in which all 95 avian influenza viruses contain L (Leu), whereas all 306 human influenza viruses contain P (Pro). The other 2 residues with zero entropy value in avian and human viruses are located at position 55 of PA, in which we have D (Asp) in avian viruses and N (Asn) in human viruses, and position 121 of M1, in which we have T (Thr) in avian and A (Ala) in human viruses. Entropy plots for all 11 influenza viral proteins can be found in Figure A1.

Figure panel B shows a genomewide view of the entropy plots for 11 influenza A viral proteins. The amino acid sequences of hemagglutinin (HA), with an average entropy value of –0.524 within avian viruses and –0.158 within human viruses, exhibit much more diversity than other open reading frames (ORFs). PB2, PB1, PA, NP, and M1, on the other hand, are more conserved (i.e., they have less negative entropy values).

Figure.

A) Entropy plot for avian versus human influenza viruses for NP amino acid residues. In each aligned position, we have a consensus residue for 95 avian strains displayed on top and a consensus residue for 306 human strains at the bottom. Completely conserved amino acid positions are filled with white; less conserved amino acids are filled in various gray shadings. Positions in which 1 single residue dominates >90%, <90% but >75%, and <75% are labeled with red, yellow, and green letters, respectively. Yellow rectangles indicate that both human and avian viruses are completely conserved to the same residue; magenta rectangles indicate that avian and human viruses are each completely conserved to a different residue. B) Entropy plots for the entire influenza A viral genome. Each lane displays entropy value distributions of aligned protein sequences for 1 of the 11 viral proteins; the upper half represents 95 avian strains, and the bottom half represents 306 human strains. (PB1-F2 contains fewer strains, as described in Discussion.) Positions completely conserved to a single residue are shown in a white band, while less conserved ones are shown in various gray shadings. The average entropy for the entire segment is shown to the right of these lanes. Entropy values are zero when residues are completely conserved; more negative values indicate more diversity. Alignment size for each protein from top to bottom is 759, 757, 90, 716, 591, 498, 480, 252, 97, 230, and 121.

In addition to the previously mentioned 3 positions with distinct amino acid residues between avian and human strains, we found 225 additional positions with nearly distinct amino acid residues, with their computed entropy values less negative than –0.4 in both the 306 human and 95 avian strains that we analyzed. To assess the robustness of those 228 residues used in differentiating human from avian influenza viruses, we further examined 15,785 influenza A protein sequences from NCBI. After validation, 52 positions still showed an entropy value less negative than –0.4 and conserved to distinct amino acid residues between human and avian viruses (Table 1). From this entropy analysis, we identified an additional 51 aa positions that may be as important as the well-known position 627 of PB2. We designated these 52 positions as "species-associated" signatures. Among 11 ORFs, NP contains the highest number of such signatures (15 positions), followed by PA (10 positions), PB2 (8 positions), PB1-F2 (5 positions), M2 (4 positions), M1 (3 positions), PB1 (2 positions), HA (2 positions), NS2 (2 positions), and NS1 (1 position). No signature was found in the NA gene. We also summarized the related functions of those species-associated signatures in Table 1. The complete results of genome scanning and validation can be found in Table A3 and Table A4.

Table 1. Validated amino acid signatures separating avian influenza viruses from human influenza viruses*.

| Gene | Position | Avian residues | Human residues | Associated functional domains |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB2 | 44 | A(208),S(7) | S(831),A(10),L(2) | PB1–1, NP-1 (9), MLS (10) |

| 199 | A(210),S(5) | S(842),A(3) | NP-1 (9) | |

| 271 | T(210),A(3),I(1),M(1) | A(836),T(6),S(1) | Cap-N (11) | |

| 475 | L(214),M(1) | M(839),L(3) | NLS (12) | |

| 588 | A(203),T(6),V(6) | I(835),V(3),A(2) | PB1–2, NP-2 (9) | |

| 613 | V(212),A(3) | T(816),I(16),A(8),V(1) | PB1–2, NP-2 (9) | |

| 627 | E(196),K(19) | K(838),R(2),E(1) | PB1–2, NP-2 (9) | |

| 674 | A(204),S(6),T(2),G(2),E(1) | T(836),A(2),I(2),P(1) | PB1–2, NP-2 (9) | |

| PB1 | 327 | R(147),K(3) | K(766),R(66) | cRNA (13) |

| 336 | V(142),I(8) | I(773),V(59) | cRNA (13) | |

| PB1-F2 | 73 | K(397),R(6),I(1) | R(594),K(87),S(1) | ANT3, VDAC1 (14), mitochondrial localization (15), predicted amphipathic helix (16) |

| 76 | V(401),A(3) | A(625),V(57) | ANT3, VADC1 (14), predicted amphipathic helix (16) | |

| 79 | R(369),Q(34),L(1) | Q(607),R(75) | ANT3, VADC1 (14), predicted amphipathic helix (16) | |

| 82 | L(382),S(22) | S(596),L(86) | ANT3, VADC1 (14), predicted amphipathic helix (16) | |

| 87 | E(389),G(14),K(1) | G(637),E(45) | ANT3, VADC1 (14) | |

| PA | 28 | P(213),S(1) | L(831),P(9),R(2) | Proteolysis (17) |

| 55 | D(214) | N(836),D(5) | Proteolysis (17) | |

| 57 | R(210),Q(4) | Q(829),R(6),L(4),K(2) | Proteolysis (17) | |

| 225 | S(213),C(1) | C(829),S(10) | Proteolysis (17), NLSII (18) | |

| 268 | L(214) | I(827),L(11), P(1) | ||

| 356 | K(212),X(1),R(1) | R(827),K(11) | ||

| 382 | E(208),D(5),V(1) | D(824),E(11),V(2),N(1) | ||

| 404 | A(214) | S(828),A(9),P(1) | ||

| 409 | S(189),N(24),I(1) | N(830),S(7),I(1) | ||

| 552 | T(213),N(1) | S(835),T(1),I(1) | ||

| HA | 237 | N(582),R(49),D(2),H(1),S(1) | R(1209),N(12),S(2),D(1),K(1) | |

| 389 | D(659),N(20),G(1),Y(1) | N(819),D(121) | ||

| NP | 16 | G(356),S(9),D(6),T(2) | D(646),G(7) | RNA binding (19), BAT1/UAP56 (20), MxA (21), PB2–1 (22) |

| 33 | V(355),I(18) | I(638),V(15) | RNA binding (19), MxA (21), PB2–1 (22) | |

| 61 | I(366),M(6),V(1) | L(642),I(8) | RNA binding (19), MxA (21), PB2–1 (22) | |

| 100 | R(360),K(11),V(2) | V(619),I(32),A(1),M(1) | RNA binding (19), MxA (21), PB2–1 (22) | |

| 109 | I(359),V(10),M(2),T(2) | V(614),I(34),T(3),A(2) | RNA binding (19), MxA (21), PB2–1 (22) | |

| 214 | R(352),K(20),L(1) | K(640),R(10) | NLS (23), CRM1 (24), NP-1 (25) | |

| 283 | L(372),P(1) | P(643),L(7) | NP-1 (25), PB2–2 (22) | |

| 293 | R(371),K(2) | K(622),R(28) | NP-1 (25), PB2–2 (22) | |

| 305 | R(369),K(4) | K(636),R(14) | NP-1 (25), PB2–2 (22) | |

| 313 | F(371),I(1),L(1) | Y(642),F(8) | NP-1 (25), PB2–2 (22) | |

| 357 | Q(368),K(4),T(1) | K(644),R(8),Q(1) | NAS (26), NP-1 (25), PB2–3 (22) | |

| 372 | E(357),D(15),K(1) | D(630),E(23) | NAS (26), NP-2 (25), PB2–3 (22) | |

| 422 | R(373) | K(630),R(23) | CTL epitope (27), NP-2 (25), PB2–3 (22) | |

| 442 | T(372),A(1) | A(629),T(23),R(1) | NP-2 (25), PB2–3 (22) | |

| 455 | D(373) | E(630),D(22),T(1) | NP-2 (25), PB2–3 (22) | |

| M1 | 115 | V(856),I(2),L(1),G(1) | I(981),V(9) | |

| 121 | T(840),A(19),P(1) | A(988),T(2) | ||

| 137 | T(859),A(1),P(1) | A(974),T(12) | ||

| M2 | 11 | T(434),I(11),S(2) | I(911),T(44) | Host restriction specificities (28), ectodomain (29) |

| 20 | S(471),N(13) | N(926),S(29) | Host restriction specificities (28). ectodomain (29) | |

| 57 | Y(481),C(1),H(1) | H(913),Y(33),R(2),Q(1) | CRAC (30), endodomain (29) | |

| 86 | V(378) | A(924),V(10),T(4),D(1) | Endodomain (29) | |

| NS1 | 227 | E(692),G(9),K(1),S(1) | R(897),G(5),K(1),E(1) | |

| NS2 | 70 | S(453),G(21),D(1) | G(903),S(2) | M1, NEP dimerization domain (31) |

| 107 | L(468),S(2),F(1) | F(777),L(16),S(1) | M1, NEP dimerization domain (31) |

*Numbers in parentheses in residue columns are the number of sequences yielding the specific amino acid residue; bold indicates dominant amino acid residue type.

Amino Acid Signatures in Human Viruses

We examined how the amino acid sequences varied at those proposed signature positions for avian influenza viruses isolated from humans. At 9 of these 52 positions, residue changes were characteristic of human rather than avian viruses (Table 2). For example, 34 sequences (27 H5N1, 3 H9N2, and 4 H7N7) were available for inspection at position 199 of PB2 (data not shown). Aside from 10 sequences with gaps (sequences did not cover this position), 19 of the remaining 24 still have Ala, which is typical for avian viruses. Five of them (all H5N1), on the other hand, have this residue changed to Ser, which is mostly seen in human viruses. At the well-known position 627 of PB2, 5 sequences had gaps, 22 retained Glu (typical for avian virus), while the other 7 changed to Lys, which is typical for human virus. Among those 7 mutated sequences, 6 were from H5N1 human isolates (A/Hong Kong/483/1997, A/Hong Kong/485/1997, A/Vietnam/1194/2004, A/Vietnam/1203/2004, A/Vietnam/3062/2004, and A/Thailand/16/2004), and the other 1 was A/Netherlands/219/2003(H7N7), which was isolated from a fatal human case of pneumonia in the Netherlands (32).

Table 2. Summary of host-associated amino acid signature changes.

| Gene | Position | Residue* | H5N1 | H9N2 | H7N2 | H7N7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB2 | 199 | A(19) | 15 | 3 | 1 | |

| S(5) | 5 | |||||

| 271 | T(23) | 20 | 2 | 1 | ||

| A(1) | 1 | |||||

| 627 | E(22) | 19 | 3 | |||

| K(7) | 6 | 1 | ||||

| PB1-F2 | 73 | K(24) | 17 | 2 | 5 | |

| R(2) | 2 | |||||

| 79 | R(24) | 17 | 2 | 5 | ||

| Q(2) | 2 | |||||

| 82 | L(21) | 19 | 2 | |||

| S(5) | 5 | |||||

| PA | 409 | S(17) | 12 | 3 | 2 | |

| N(7) | 7 | |||||

| M2 | 20 | S(34) | 31 | 2 | 1 | |

| N(5) | 5 | |||||

| NS2 | 70 | S(26) | 22 | 2 | 2 | |

| G(1) | 1 |

*Top half displays an avian-specific residue with the count in parentheses and distribution among subtypes, and the bottom half represents a human-specific residue.

To understand how mutations had accumulated within a specific virus, we summarized the amino acid changes for 21 of these avian viruses that contained full or nearly full-length sequences for each segment (Table 3). We found that 19 of 21 strains contained >1 species-associated amino acid change, and 7 of them contained >2 substitutions; A/Netherlands/219/2003(H7N7) had the highest count for mutation accumulation (3 positions). Among these 52 species-associated signatures, the mutation combinations at positions PB2 199 and PA 409 were most commonly seen in H5N1 human isolates from Hong Kong in 1997.

Table 3. Twenty-one avian influenza A viral genomes isolated from humans and their mutations found at 12 host-associated positions within each strain*.

| Strain | Subtype | PB2 |

PB1-F2 |

PA |

M2 |

NS2 |

Mutations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 199 | 271 | 627 | 73 | 79 | 82 | 409 | 20 | 70 | |||

| A/Hong Kong/156/1997 | H5N1 | S | T | E | K | R | L | N | S | S | 2 |

| A/Hong Kong/481/1997 | H5N1 | A | T | E | K | R | L | N | S | S | 1 |

| A/Hong Kong/482/1997 | H5N1 | S | T | E | K | R | L | N | S | S | 2 |

| A/Hong Kong/483/1997 | H5N1 | A | T | K | K | R | L | S | S | S | 1 |

| A/Hong Kong/485/1997 | H5N1 | A | T | K | # | # | # | S | S | S | 1 |

| A/Hong Kong/486/1997 | H5N1 | S | T | E | K | R | L | N | S | S | 2 |

| A/Hong Kong/532/1997 | H5N1 | A | T | E | K | R | L | N | S | S | 1 |

| A/Hong Kong/538/1997 | H5N1 | S | T | E | K | R | L | N | S | S | 2 |

| A/Hong Kong/542/1997 | H5N1 | A | T | E | K | R | L | N | S | S | 1 |

| A/Hong Kong/1997/1998 | H5N1 | S | T | E | K | R | L | S | S | S | 1 |

| A/Hong Kong/212/2003 | H5N1 | A | T | E | R | R | L | S | S | S | 1 |

| A/Hong Kong/213/2003 | H5N1 | A | T | E | R | R | L | S | S | S | 1 |

| A/Thailand/16/2004 | H5N1 | A | T | K | K | Q | L | S | S | S | 2 |

| A/Thailand/SP83/2004 | H5N1 | A | T | E | K | Q | L | S | S | S | 1 |

| A/Vietnam/1194/2004 | H5N1 | A | T | K | K | R | L | S | S | S | 1 |

| A/Vietnam/1203/2004 | H5N1 | A | T | K | K | R | L | S | S | S | 1 |

| A/Vietnam/3062/2004 | H5N1 | A | T | K | K | R | L | S | S | S | 1 |

| A/Netherlands/219/2003 | H7N7 | A | T | K | K | R | S | S | N | S | 3 |

| A/Guangzhou/333/1999 | H9N2 | A | A | E | # | # | # | S | S | G | 2 |

| A/Hong Kong/1073/1999 | H9N2 | A | T | E | K | R | L | S | R | S | 0 |

| A/Hong Kong/1074/1999 | H9N2 | A | T | E | K | R | L | S | S | S | 0 |

*#indicates strains with PB1 RNA encoded into a truncated form of PB1-F2 of only 57 amino acids long. Boldface letters represent mutated (human-specific) residues; Roman (nonbold) letters are used for regular avian residue. Note that at position 20 of M2, A/Hong Kong/1073/99 had its residue changed from S to R, where R is still considered a mutation within avian species.

RNA Segment 5

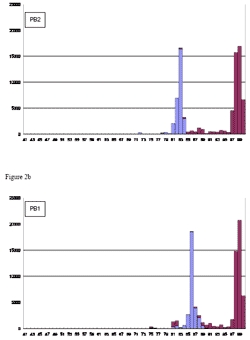

Our observation that NP contained the highest number (15 of 52) for species-associated amino acids suggested that NP might serve as a molecular target for differentiation between human and avian influenza A viruses. To indicate such host specificity, or the "genetic boundary" between these 2 viruses at the nucleotide level, we performed a pairwise sequence comparison for all 11 ORFs on our 401-genome primary dataset and produced histograms on their computed pairwise identities. In Figure A2, pairs with 2 sequences of the same host species (human to human, or avian to avian; termed homopairs) and pairs for sequences that cross host species (human to avian, or avian to human; termed heteropairs) are shown. HA and NA genes exhibited considerable sequence differences between strains, with identities as low as 47%. Also noted was a wide spectrum of percent identities (e.g., 55%–95% in the horizontal axis) containing few sequence pairs for these 2 genes. For both of these proteins, some strains from the same species can have identities as low as 50%. However, the ORF of another surface protein, M2 ion channel protein, is relatively conserved (>74% identity for viruses across species). The histograms for the polymerase genes (PB2, PB1, and PA), NP, and M1, on the other hand, are much less varied (mostly <20% variation). In particular, the NP gene was found to exhibit a fairly clear boundary between homopairs and heteropairs, at ≈86%.

Discussion

The glutamic acid residue at PB2 627, which is commonly seen in avian viruses, restricts viral growth in humans and monkeys, but a change to lysine restores virus replication in mammalian cells (33). In this study we computed for every amino acid position (distributed in the 11 known influenza viral ORFs) an entropy value that represents how conserved an amino acid residue is at that given position. We found the entropy value –0.379 at 627 of PB2 and therefore used –0.4 as a threshold to discover other amino acid residues that might be potential determinants of host-cell tropism. Another 51 positions were found to be distinct or nearly distinct between human and avian viruses by this entropy threshold. Most of these (40 of 52) are located in viral ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) (PB2, PB1, PA, and NP), which are essential for viral replication. Taubenberger et al. reported 10 amino acid residues that distinguish human and avian influenza viral polymerases (3). Six of them were also identified in this study. The entropy values of the 4 missing ones were also found close to the preset threshold (–0.4). For example, PB2 567 showed a human entropy of –0.039 and avian entropy of –0.490, PB1 375 with human entropy –0.165 and avian entropy –0.693, and PA 100 with human entropy –0.061 and avian entropy –0.406. All 3 positions were eliminated earlier from the stage of analyzing the 401-genome primary dataset. The fourth position, PB2 702, although in the first-round list, marginally failed in the subsequent validation with human entropy –0.057 and avian entropy –0.404.

We proposed a computational approach capable of indicating species-associated signatures in studying human versus avian influenza viral genomes. Although we intended to analyze a comprehensive set of avian versus human influenza A viral genomes, the available sequences are predominated by H5N1 in avian viruses and H3N2 in human viruses. The short supply of sequences other than those 2 subtypes may inevitably cause a certain amount of bias in our results. At the completion of this study, we noticed a recent article by Obenauer et al., who had made 169 newly sequenced avian influenza viral genomes available to GenBank on January 26, 2006 (34); these were not included in our analysis. We checked on our 52 signature positions against these new genomes and found only 2 of them that showed an entropy value slightly over our threshold –0.4. These are PB1-F2 87 and HA 237, with entropy values of –0.522, and –0.692, respectively. The choice of entropy threshold would also affect the number of signatures found. Originally we chose –0.4 on the basis of the value –0.379, computed from PB2 627 by using 95 avian genomes. We noticed that this entropy value reduced to –0.299 at PB2 627 (see Table A4) at the later validation stage, when we found 197 E and 19 K from a total of 215 avian PB2 sequences. If we chose to use a more stringent entropy threshold of –0.3, our analysis still showed 46 of those 52 reported signatures; missing were positions 73, 79, and 82 from PB1-F2, 409 from PA, and 237 and 389 from HA.

In addition to the data limitations, this approach of looking for species-associated signatures by entropy is less useful for HA and NA genes. The genetic diversity that exists in either human or avian viruses for these 2 gene segments can markedly boost their respective entropy to more negative values, thus making it difficult to find residues conserved enough for identifying such signatures. We additionally performed the analysis on human H1, H2, and H3 versus avian HA (Figure A1). For NA we performed the analysis on human N1 and N2 versus avian NA. We compared 10 human H1, 3 human H2, and 293 human H3 with 95 avian HA sequences and found 13, 13, and 69 signatures (with entropy values for both human and avian within –0.4), respectively. This finding indicates that the human H1 and H2 strains are less distinct from avian strains (H5 dominant) than H3. For NA we found only 6 signatures, in comparison with 8 human N1 versus 95 avian (N1-dominant), and we found only 5 signatures when we compared 298 human N2 and 95 avian sequences. Entropy plots for these analyses can be seen in Figure A1.

Two genetic alleles (allele A and B) have been described for the NS gene in avian influenza A virus. We decomposed those 95 avian NS genes into 43 in allele A and 52 in allele B and compared their amino acid sequences with 306 human NS genes. For NS1, 6 signatures were found between human viruses and avian allele A viruses, and 35 signatures were found between human viruses and avian allele B viruses. For NS2, 3 signatures were found between human viruses and allele A viruses, and 6 signatures were found between human viruses and allele B viruses. These results suggest that avian allele B viruses are more distinct from human viruses than are allele A viruses. Entropy plots and histograms for these analyses can be seen in Figure A1 and Figure A3.

From the histograms, we found that some of the 11 genes vary greatly between human and avian viruses, while some others vary little. No boundaries were found between homopairs and heteropairs for HA, NA, and PB1 for human versus avian viruses. This finding seems reasonable because the 2 recent pandemic strains, the 1957 H2N2 and the 1968 H3N2, both originated from reassortment with avian influenza viruses (HA, NA, and PB1 gene segments were from avian influenza). On the other hand, because histograms of NP, followed by PA and PB2, may be used to distinguish human influenza viruses from avian influenza viruses, perhaps some biologic constraints against the occurrence of reassortment exist for these 3 genes. Both the M and NS genes are less differentiable between these 2 types of influenza A viruses.

NP not only displays a clear boundary between human and avian viruses from histogram analysis but also contains more species-associated amino acid signatures (15 of 52) than other ORFs. In addition to NP, polymerase proteins PB2, PB1, and PA also contain abundant species-associated signatures. Most signatures in these viral RNPs are located on the functional domains related to RNP-RNP interactions that are necessary to form replicase/transcriptase complex (3P and NP), which suggests that specific combinations of polymerase complex and NP would allow an influenza virus to replicate itself efficiently (Table 1). In addition to RNA-interacting domains, many species-associated amino acid signatures of 3P and NP are located in regions related to nuclear localization signals. Influenza viral replication is highly dependent on nuclear function (35), making it worthwhile to further examine the roles of those amino acid signatures on nuclear localization of viral RNP in avian versus human cells. We also noticed that several amino acid signatures in NP are located in the regions that interact with cellular proteins, such as splicing factor (BAT1/UAP56) or MxA, which plays a certain role in cellular antiviral mechanisms. What species-specific host factors may affect influenza viral replication rates is not clear. Biologic experiments are required for further understanding the roles of those amino acid residues and related functional domains in the mechanism of interspecies infection.

PB1-F2 is a novel influenza viral protein translated from alternative initiation of PB1 gene. PB1-F2 of PR8 (H1N1) has been shown to target mitochondria and then trigger host cell apoptosis (36). Our previous research has found that several strains contain truncated PB1-F2 (37). In this study, 379 of 401 PB1 sequences (in the primary dataset) contained PB1-F2 >87 and <90 aa. For the other 22 sequences, 2 H3N2 strains missed a start codon, 3 H3N2 had the translation stopped at 11 aa, 1 H9N2 stopped at 8 aa, 5 H1N1 stopped at 57 aa, and 3 H9N2 and 7 H3N2 stopped at 79 aa. One H5N1 contained extra residues; its PB1-F2 was 101 aa. We also noted 5 species-associated signatures on PB1-F2; all of them are within the C-terminal domain, which is important for mitochondria targeting (15,16). Further investigation of the mitochondria localization of those PB1-F2 variants and their abilities for triggering apoptosis in cells derived from different species is warranted.

How many mutations would make an avian virus capable of infecting humans efficiently, or how many mutations would render an influenza virus a pandemic strain, is difficult to predict. We have examined sequences from the 1918 strain, which is the only pandemic influenza virus that could be entirely derived from avian strains. Of the 52 species-associated positions, 16 have residues typical for human strains; the others remained as avian signatures. The result supports the hypothesis that the 1918 pandemic virus is more closely related to the avian influenza A virus than are other human influenza viruses (2). From the 21 avian viruses isolated from humans in this study, we found 19 (90.5%) that contain >1 change at the species-associated sites. Upon examining signature changes from similarly sized sets of randomly selected human viruses, randomly selected avian viruses, and randomly selected viruses (avian plus human), we found 29.4%, 71.4%, and 47.1%, respectively, contain species-associated mutations. Although predicting the emergence of a pandemic strain is difficult, close monitoring of how those species-associated signature positions have changed from bird-specific to human-specific signatures may provide a measurement for the prediction of such events.

Appendix

Supporting Materials and Methods

In the main text we have mentioned an entropy value was defined at an aligned amino acid position according to the formula ΣPi*log(Pi), where i is the observed probability for each of the 20 amino acids. An entropy value defined like this is at most zero when all amino acids at this position conserve to the same residue, while a more negative value indicates that the residues are more divergent for containing more residue types. Although BioEdit also includes a module with similar formula in computing entropy values for aligned sequences, we chose to develop our own software for more streamlined data manipulation and subsequent analysis and interpretation.

To reveal the host-associated amino acid signatures, we have retrieved full genome sequences (as of August 22, 2005) from the genome browser at Influenza Sequence Database. Strains containing all eight RNA segments and for each segment a minimum 90% long of the coding sequence based on PR8 were included, which serve as the primary dataset for full genome scanning. Altogether, we have 95 avian influenza genomes (including 60 H5N1, 8 H6N1, 6 H6N2, 1 H7N1, 1 H7N3, 2 H7N7, 17 H9N2) and 306 human influenza genomes (8 H1N1, 2 H1N2, 3 H2N2 and 293 H3N2), the latter include 11 complete genomes of Taiwanese strains from 1996 to 2004 (newly sequenced data from this study). See Supporting Table 1 for a complete listing of accessions for these 401 genomes. Coding sequence alignments for each genomic segment were compiled: PB2, 759 aa; PB1, 757 aa; PB1-F2, 90 aa; PA, 716 aa; HA, 591 aa; NP, 498 aa; NA, 480 aa; M1, 252 aa; M2, 97 aa; NS1, 230 aa; and NS2, 121 aa.

Human-isolated avian influenza viruses from human flu were separately retrieved from NCBI as well as from ISD. Altogether we have 417 accessions from 60 avian flu strains (48 H5N1, 6 H9N2, 5 H7N7 and 1 H7N2), in which 21 strains (17 H5N1, 3 H9N2 and 1 H7N7) contain sequences (full or nearly full-length) from all 8 genomic RNAs. See Table A2 for a complete listing of these accessions.

For validating the obtained signatures from analyzing the mentioned 401-genome primary dataset, we have firstly retrieved 14,057 human or avian influenza A protein sequences from NCBI's Influenza Virus Resources (as of January 17, 2006), including 5,468 avian and 8,589 human sequences (786 H1N1 sequences and 7,097 H3N2 sequences among the others). At the stage of revising this manuscript, we have included more H1N1sequences (2,514 in total, as of April 20, 2006) for validation to relieve the limitation that may be caused by the unbalanced sequence counts between H1N1 (786 sequences) and H3N2 (7,097 sequences) previously used, thus making the results more robust. Altogether we have used 15,785 influenza protein sequences for confirmatory analysis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from National Science Council (NSC) Taiwan, NSC 93-2218-E-182-002, NSC 94-2213-E-182-027, and DOH95-DC-1413 (Department of Health, Taiwan).

Biography

Dr Chen is an assistant professor at the Department of Computer Science and Information Engineering, Chang Gung University. His research interests include viral bioinformatics, biological sequence analysis, data mining, and software development.

Table A1. Listing of 401 genomes used in this study. All accessions are according to GenBank, except for A/Puerto Rico/8/34(H1N1), which are from Influenza Sequence Database (ISD). Full table available at www.cdc.gov/eid-static/spreadsheets/06-0276-TA1.xlsx.

Table A2. Listing of 60 human-isolated avian influenza viruses used in this study, with the first 29 strains contain at least one accession per genomic segment. All accessions here are according to GenBank, except those ones begin with 'ISD', which are from Influenza Sequence Database (ISD). Cells with 'n/a' in PB1-F2 column indicate that the PB1 RNA sequence did not contain the PB1-F2 ORF, while 'truncated' represent early-terminated PB1-F2 with a length less than 87-aa. Exclusion of those PB1-F2 leaves us 21 genomes for inspecting the species-associated mutations as described in the text.

Table A3. Genome-scanning for 228 amino acid 'signatures' (those ones shown in bold face, either 'Distinct' or 'Nearly Distinct') out of 4,591 aligned amino acid positions. Con: consensus residue; Ent: entropy value; Same: all avian and human strains conserve to the same residue; Nearly Identical: both avian and human strains have entropy values less negative than -0.4, and have the same residue; Distinct: both avian and human strains contain zero entropy yet conserve to the different residue; Nearly Distinct: both avian and human strains contain an entropy value less negative than -0.4, and conserve to different residue. The last column shows positions based on PR8. Only HA and NA have different numberings comparing with the first column, due to excessive shifting of amino residues from HA and NA genetic diversity. Full table available at www.cdc.gov/eid-static/spreadsheets/06-0276-TA3.xlsx.

| Scanning for amino acid 'signatures' for influenza A virus PB2 protein |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos | Avian |

Human |

Comments | PR8 | ||||

| Con | Ent | Residues | Con | Ent | Residues | |||

| 1 | M | -0.500 | M(76),-(19), | M | -0.055 | M(303),-(3), | ||

| 2 | E | -0.293 | E(88),K(1),-(6), | E | -0.061 | E(303),V(1),-(2), | Nearly Identical | |

| 3 | R | -0.175 | R(91),-(4), | R | -0.022 | R(305),T(1), | Nearly Identical | |

| 4 | I | -0.140 | I(92),-(3), | I | -0.022 | I(305),L(1), | Nearly Identical | |

| 5 | K | -0.140 | K(92),-(3), | K | -0.039 | R(2),K(304), | Nearly Identical | |

| 6 | E | -0.140 | E(92),-(3), | E | 0.000 | E(306), | Nearly Identical | |

| 7 | L | -0.160 | L(92),F(1),-(2), | L | 0.000 | L(306), | Nearly Identical | |

| 8 | R | -0.160 | R(92),W(1),-(2), | R | 0.000 | R(306), | Nearly Identical | |

| 9 | D | -0.521 | N(1),D(83),E(7),Y(2),-(2), | N | -0.619 | N(227),D(1),S(2),T(76), | ||

| 10 | L | -0.160 | I(1),L(92),-(2), | L | -0.022 | I(1),L(305), | Nearly Identical | |

| 11 | M | -0.117 | I(1),M(93),-(1), | M | 0.000 | M(306), | Nearly Identical | |

| 12 | S | 0.000 | S(95), | S | -0.022 | L(1),S(305), | Nearly Identical | |

| 13 | Q | 0.000 | Q(95), | Q | 0.000 | Q(306), | Same | |

| 14 | S | 0.000 | S(95), | S | -0.022 | F(1),S(305), | Nearly Identical | |

| 15 | R | 0.000 | R(95), | R | 0.000 | R(306), | Same | |

| 16 | T | -0.058 | S(1),T(94), | T | 0.000 | T(306), | Nearly Identical | |

| 17 | R | 0.000 | R(95), | R | 0.000 | R(306), | Same | |

| 18 | E | 0.000 | E(95), | E | 0.000 | E(306), | Same | |

| 19 | I | 0.000 | I(95), | I | 0.000 | I(306), | Same | |

| 20 | L | 0.000 | L(95), | L | -0.022 | L(305),V(1), | Nearly Identical | |

| 21 | T | 0.000 | T(95), | T | 0.000 | T(306), | Same | |

| 22 | K | 0.000 | K(95), | K | -0.022 | N(1),K(305), | Nearly Identical | |

| 23 | T | 0.000 | T(95), | T | -0.022 | P(1),T(305), | Nearly Identical | |

| 24 | T | 0.000 | T(95), | T | 0.000 | T(306), | Same | |

| 25 | V | 0.000 | V(95), | V | 0.000 | V(306), | Same | |

Table A4. Amino acid 'signatures' validation. Only positions with both newly computed entropy values less or equal to -0.400 are considered 'validated'. This reduces 228 signatures to a count of 52 (the ones shown in bold face) as reported in the manuscript. Cnt: total number of avian or human residues at this position; Ent: computed entropy value; PR8: position numbering based on PR8 (only HA and NA have different numbering here). Full table available at www.cdc.gov/eid-static/spreadsheets/06-0276-TA4.xlsx.

| Gene | Pos | Avian influenza viruses |

Human influenza viruses |

Validated? | PR8 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cnt | Ent | Residues | Cnt | Ent | Residues | ||||

| PB2 | 44 | 215 | -0.144 | A(208),S(7), | 843 | -0.081 | A(10),L(2),S(831), | Yes | |

| 67 | 215 | -0.174 | I(206),V(9), | 843 | -0.538 | I(193),V(650), | |||

| 81 | 215 | -0.196 | A(2),I(7),T(206), | 843 | -0.537 | I(2),L(4),M(686),T(4),V(147), | |||

| 82 | 215 | -0.164 | R(1),N(209),K(1),S(2),T(2), | 843 | -0.608 | N(180),C(14),S(648),X(1), | |||

| 120 | 215 | 0.000 | E(215), | 843 | -0.575 | N(1),D(628),E(214), | |||

| 199 | 215 | -0.110 | A(210),S(5), | 845 | -0.024 | A(3),S(842), | Yes | ||

| 227 | 215 | 0.000 | V(215), | 845 | -0.697 | I(586),M(19),V(240), | |||

| 271 | 215 | -0.133 | A(3),I(1),M(1),T(210), | 843 | -0.051 | A(836),S(1),T(6), | Yes | ||

| 382 | 215 | -0.110 | I(210),V(5), | 842 | -0.527 | I(185),V(657), | |||

| 453 | 215 | -0.164 | Q(2),H(1),L(2),P(209),S(1), | 842 | -0.497 | R(1),H(691),L(1),P(147),S(2), | |||

| 456 | 215 | -0.219 | N(205),D(6),S(4), | 842 | -0.623 | N(247),D(1),C(1),S(593), | |||

| 461 | 215 | -0.159 | I(207),V(8), | 842 | -0.638 | I(283),V(559), | |||

| 463 | 215 | -0.247 | I(203),L(1),M(1),V(10), | 842 | -0.529 | I(181),M(1),V(660), | |||

| 475 | 215 | -0.030 | L(214),M(1), | 842 | -0.024 | L(3),M(839), | Yes | ||

| 478 | 215 | -0.484 | I(30),L(1),M(2),V(182), | 842 | -0.541 | I(656),L(2),V(184), | |||

| 526 | 215 | -0.053 | R(2),K(213), | 841 | -0.577 | R(619),K(222), | |||

| 559 | 215 | -0.255 | I(5),M(2),T(204),V(4), | 841 | -0.694 | A(547),N(1),I(2),T(287),V(4), | |||

| 588 | 215 | -0.254 | A(203),T(6),V(6), | 841 | -0.050 | A(2),I(835),V(3),X(1), | Yes | ||

| 613 | 215 | -0.073 | A(3),V(212), | 841 | -0.157 | A(8),I(16),T(816),V(1), | Yes | ||

| 627 | 215 | -0.299 | E(196),K(19), | 841 | -0.026 | R(2),E(1),K(838), | Yes | ||

Figure A1.

Entropy plot for all 11 influenza proteins for human (top) versus avian (bottom). In each aligned position, we have a consensus residue for 95 avian strains displayed on top, and a consensus residue for 306 human strains at the bottom. Completely conserved amino acid positions are filled with white, while less conserved amino acids are filled in various gray shadings. Positions where one single residue dominates over 90%, less than 90% but greater than 75%, and less than 75% are labeled with red, yellow, and green letters, respectively. Yellow rectangles indicate that both human and avian flu are completely conserved to the same residue, while rectangles in magenta indicate that avian and human flu each completely conserves to a different residue Additional plots for HA, NA, NS1 and NS2, for using different counts of human or avian strains are detailed as individual captions to these plots. Adobe Acrobat PDF available at http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/pdfs/06-0276-FA1.pdf (21 pages).

Figure A2.

Histograms on comparing 306 human versus 95 avian influenza A viruses, based on nucleotide pairwise sequence identities. Vertical axis shows the count for pairs of sequences with specific percent identity (rounded to integer). Red bars represent frequencies for 'homo' pairs – sequences of the same host species (human to human, or avian to avian); blue bars represent frequencies for 'hetero' pairs – pairs that cross host species (human to avian, or avian to human). Adobe Acrobat PDF available at http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/pdfs/06-0276-FA2.pdf (6 pages).

Figure A3.

Histograms compare 43 avian allele A viruses and 306 human viruses (panels A and C), and 52 avian allele B viruses and 306 human viruses (panels B and D), based on their NS1 and NS2 genomic segments. Vertical axis shows the count for pairs of sequences with specific percent identity (rounded to integer). Red bars represent frequencies for 'homo' pairs – sequences of the same host species (human to human, or avian to avian); blue bars represent frequencies for 'hetero' pairs – pairs that cross host species (human to avian, or avian to human). Adobe Acrobat PDF available at http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/pdfs/06-0276-FA3.pdf (5 pages).

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Chen G-W, Chang S-C, Mok C-K, Lo Y-L, Kung Y-N, Huang J-H, et al. Genomic signatures of human versus avian influenza A viruses. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2006 Sep [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1209.060276

These authors contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Scholtissek C, Rohde W, von Hoyningen V, Rott R. On the origin of the human influenza virus subtypes H2N2 and H3N2. Virology. 1978;87:13–20. 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90153-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reid AH, Taubenberger JK, Fanning TG. Evidence of an absence: the genetic origins of the 1918 pandemic influenza virus. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:909–14. 10.1038/nrmicro1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taubenberger JK, Reid AH, Lourens RM, Wang R, Jin G, Fanning TG. Characterization of the 1918 influenza virus polymerase genes. Nature. 2005;437:889–93. 10.1038/nature04230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang SC, Cheng YY, Shih SR. Avian influenza virus: the threat of a pandemic. Chang Gung Med J. 2006;29:130–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16:276–7. 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02024-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. p. 95–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen GW, Hsiung CA, Chyn JL, Shih SR, Wen CC, Chang IS. Revealing molecular targets for enterovirus type 71 detection by profile hidden Markov models. Virus Genes. 2005;31:337–47. 10.1007/s11262-005-3252-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macken C, Lu H, Goodman J, Boykin L, Boykin L. The value of a database in surveillance and vaccine selection. In: Osterhaus A, Cox N, Hampson AW, editors.Options for the control of influenza IV. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 2001. p. 103–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poole E, Elton D, Medcalf L, Digard P. Functional domains of the influenza A virus PB2 protein: identification of NP- and PB1-binding sites. Virology. 2004;321:120–33. 10.1016/j.virol.2003.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carr SM, Carnero E, Garcia-Sastre A, Brownlee GG, Fodor E. Characterization of a mitochondrial-targeting signal in the PB2 protein of influenza viruses. Virology. 2006;344:492–508. 10.1016/j.virol.2005.08.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honda A, Mizumoto K, Ishihama A. Two separate sequences of PB2 subunit constitute the RNA cap-binding site of influenza virus RNA polymerase. Genes Cells. 1999;4:475–85. 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00275.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukaigawa J, Nayak DP. Two signals mediate nuclear localization of influenza virus (A/WSN/33) polymerase basic protein 2. J Virol. 1991;65:245–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez S, Ortin J. Distinct regions of influenza virus PB1 polymerase subunit recognize vRNA and cRNA templates. EMBO J. 1999;18:3767–75. 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zamarin D, Garcia-Sastre A, Xiao X, Wang R, Palese P. Influenza virus PB1–F2 protein induces cell death through mitochondrial ANT3 and VDAC1. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1:e4. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamada H, Chounan R, Higashi Y, Kurihara N, Kido H. Mitochondrial targeting sequence of the influenza A virus PB1–F2 protein and its function in mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 2004;578:331–6. 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbs JS, Malide D, Hornung F, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. The influenza A virus PB1–F2 protein targets the inner mitochondrial membrane via a predicted basic amphipathic helix that disrupts mitochondrial function. J Virol. 2003;77:7214–24. 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7214-7224.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanz-Ezquerro JJ, Zurcher T, de la Luna S, Ortin J, Nieto A. The amino-terminal one-third of the influenza virus PA protein is responsible for the induction of proteolysis. J Virol. 1996;70:1905–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nieto A, de la Luna S, Barcena J, Portela A, Ortin J. Complex structure of the nuclear translocation signal of influenza virus polymerase PA subunit. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:29–36. 10.1099/0022-1317-75-1-29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albo C, Valencia A, Portela A. Identification of an RNA binding region within the N-terminal third of the influenza A virus nucleoprotein. J Virol. 1995;69:3799–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Momose F, Basler CF, O'Neill RE, Iwamatsu A, Palese P, Nagata K. Cellular splicing factor RAF-2p48/NPI-5/BAT1/UAP56 interacts with the influenza virus nucleoprotein and enhances viral RNA synthesis. J Virol. 2001;75:1899–908. 10.1128/JVI.75.4.1899-1908.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turan K, Mibayashi M, Sugiyama K, Saito S, Numajiri A, Nagata K. Nuclear MxA proteins form a complex with influenza virus NP and inhibit the transcription of the engineered influenza virus genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:643–52. 10.1093/nar/gkh192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biswas SK, Boutz PL, Nayak DP. Influenza virus nucleoprotein interacts with influenza virus polymerase proteins. J Virol. 1998;72:5493–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weber F, Kochs G, Gruber S, Haller O. A classical bipartite nuclear localization signal on Thogoto and influenza A virus nucleoproteins. Virology. 1998;250:9–18. 10.1006/viro.1998.9329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elton D, Simpson-Holley M, Archer K, Medcalf L, Hallam R, McCauley J, et al. Interaction of the influenza virus nucleoprotein with the cellular CRM1-mediated nuclear export pathway. J Virol. 2001;75:408–19. 10.1128/JVI.75.1.408-419.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elton D, Medcalf E, Bishop K, Digard P. Oligomerization of the influenza virus nucleoprotein: identification of positive and negative sequence elements. Virology. 1999;260:190–200. 10.1006/viro.1999.9818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bullido R, Gomez-Puertas P, Albo C, Portela A. Several protein regions contribute to determine the nuclear and cytoplasmic localization of the influenza A virus nucleoprotein. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:135–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berkhoff EG, de Wit E, Geelhoed-Mieras MM, Boon AC, Symons J, Fouchier RA, et al. Functional constraints of influenza A virus epitopes limit escape from cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Virol. 2005;79:11239–46. 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11239-11246.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu W, Zou P, Ding J, Lu Y, Chen YH. Sequence comparison between the extracellular domain of M2 protein human and avian influenza A virus provides new information for bivalent influenza vaccine design. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:171–7. 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamb RA, Zebedee SL, Richardson CD. Influenza virus M2 protein is an integral membrane protein expressed on the infected-cell surface. Cell. 1985;40:627–33. 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90211-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schroeder C, Heider H, Moncke-Buchner E, Lin TI. The influenza virus ion channel and maturation cofactor M2 is a cholesterol-binding protein. Eur Biophys J. 2005;34:52–66. 10.1007/s00249-004-0424-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akarsu H, Burmeister WP, Petosa C, Petit I, Muller CW, Ruigrok RW, et al. Crystal structure of the M1 protein-binding domain of the influenza A virus nuclear export protein (NEP/NS2). EMBO J. 2003;22:4646–55. 10.1093/emboj/cdg449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fouchier RA, Schneeberger PM, Rozendaal FW, Broekman JM, Kemink SA, Munster V, et al. Avian influenza A virus (H7N7) associated with human conjunctivitis and a fatal case of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1356–61. 10.1073/pnas.0308352100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Subbarao EK, London W, Murphy BR. A single amino acid in the PB2 gene of influenza A virus is a determinant of host range. J Virol. 1993;67:1761–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obenauer JC, Denson J, Mehta PK, Su X, Mukatira S, Finkelstein DB, et al. Large-scale sequence analysis of avian influenza isolates. Science. 2006;311:1576–80. 10.1126/science.1121586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Z, Krug RM. Selective nuclear export of viral mRNAs in influenza-virus-infected cells. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:376–83. 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01794-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen W, Calvo PA, Malide D, Gibbs J, Schubert U, Bacik I, et al. A novel influenza A virus mitochondrial protein that induces cell death. Nat Med. 2001;7:1306–12. 10.1038/nm1201-1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen GW, Yang CC, Tsao KC, Huang CG, Lee LA, Yang WZ, et al. Influenza A virus PB1–F2 gene in recent Taiwanese isolates. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:630–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]