Abstract

To identify novel compounds that possess antiviral activity against hepatitis C virus (HCV), we screened a library of small molecules with various amounts of structural diversity using an HCV replicon-expressing cell line and performed additional validations using the HCV-JFH1 infectious-virus cell culture. Of 4,004 chemical compounds, we identified 4 novel compounds that suppressed HCV replication with 50% effective concentrations of ranging from 0.36 to 4.81 μM. N′-(Morpholine-4-carbonyloxy)-2-(naphthalen-1-yl) acetimidamide (MCNA) was the most potent and also produced a small synergistic effect when used in combination with alpha interferon. Structure-activity relationship (SAR) analyses revealed 4 derivative compounds with antiviral activity. Further SAR analyses revealed that the N-(morpholine-4-carbonyloxy) amidine moiety was a key structural element for antiviral activity. Treatment of cells with MCNA activated nuclear factor κB and downstream gene expression. In conclusion, N-(morpholine-4-carbonyloxy) amidine and other related morpholine compounds specifically suppressed HCV replication and may have potential as novel chemotherapeutic agents.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major human pathogen. It is associated with persistent liver infection, which leads to the development of chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (13). Treatment with pegylated interferon (IFN) and ribavirin is associated with significant side effects and is effective in only half the patients infected with HCV genotype 1 (6). More effective and more tolerable therapeutics are under development, and direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) for HCV infection are currently in advanced clinical trials. In combination with IFN and ribavirin, the HCV protease inhibitors telaprevir and boceprevir have recently been approved for treatment of genotype 1 HCV infection in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Asian countries (11, 12, 22). Although these two drugs can achieve higher sustained virologic response rates than IFN and ribavirin, their effects could be compromised by the emergence of highly prevalent drug-resistant mutants (25). Thus, it is crucial to use several different classes of DAAs in combination to improve efficacy and reduce viral breakthrough.

The HCV subgenomic replicon system has been widely used to screen compound libraries for inhibitors of viral replication, using reporter activity as a surrogate marker for HCV replication. We previously reported the successful adaptation of the Huh7/Rep-Feo replicon cell line to a high-throughput screening assay system (28). This approach contributed to the discovery of antiviral compounds, such as hydroxyl-methyl-glutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (10) and epoxide compounds (20). In our present study, we used the Huh7/Rep-Feo replicon cell line to screen a library of small molecules with various amounts of structural diversity to identify novel compounds possessing antiviral activity against HCV. We showed that the screening hit compounds inhibited HCV replication in an HCV genotype 2a (JFH-1) infectious-virus cell culture (29). The most potent compound was N′-(morpholine-4-carbonyloxy)-2-(naphthalen-1-yl) acetimidamide (MCNA). Structure-activity relationship (SAR) analyses revealed that the N-(morpholine-4-carbonyloxy) amidine moiety was a key structural element for antiviral activity. We also investigated the possible mechanisms of action of these compounds and showed that MCNA likely inhibited HCV replication through activation of the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and chemicals.

Recombinant human alpha 2b interferon (IFN-α2b) was obtained from Schering-Plough (Kenilworth, NJ), the NS3/4A protease inhibitor BILN 2061 from Boehringer Ingelheim (Ingelheim, Germany), beta-mercaptoethanol from Wako (Osaka, Japan), and recombinant human tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The library of chemicals that were screened was provided by the Chemical Biology Screening Center at Tokyo Medical and Dental University. Information about the library is available at http://bsmdb.tmd.ac.jp. The important features of the library were the abundance of pharmacophores and the great diversity. Lipinski's rule of five was used to evaluate drug similarity (15). The purity of each chemical from the library was greater than 90%. For SAR analyses, 27 compounds were purchased from Assinex (Moscow, Russia), ChemBridge (San Diego, CA), ChemDiv (San Diego, CA), Enamine (Kiev, Ukraine), Maybridge (Cambridge, United Kingdom), Ramidus AB (Lund, Sweden), SALOR (St. Louis, MO), Scientific Exchange (Center Ossipee, NH), or Vitas-M (Moscow, Russia). The chemicals were all prepared at concentrations of 10 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma) and stored at −20°C until they were used.

Cell lines and cell culture maintenance.

Huh7 and Huh7.5.1 cell lines (32) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2. The maintenance medium for the HCV replicon-harboring cell line, Huh7/Rep-Feo, was supplemented with 500 μg/ml of G418 (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan).

HCV replicon construction and cell culture.

An HCV subgenomic replicon plasmid that contained Rep-Feo, pHC1bneo/delS (Rep-Feo-1b), was derived from the HCV-N strain. RNA was synthesized from pRep-Feo and transfected into Huh7 cells. After culture in the presence of G418, a cell line that stably expressed the replicon was established (28, 31).

Cell-based screening of antiviral activity.

Huh7/Rep-Feo cells were seeded at a density of 4,000 cells/well in 100 μl of medium in 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h. Test compound solutions, 10 mM in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), were added to the wells; for primary screening, the final concentration was 5 μM. The assay plates were incubated as described above for another 48 h, and luciferase activity was measured with a luminometer (Perkin-Elmer) using the Bright-Glo Luciferase assay system (Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions. Assays were performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as means and standard deviations (SD) as percentages of the controls. Compounds were considered hits if they inhibited >50% of the mean control luciferase activities. Compounds were considered cytotoxic if they reduced cell viability below 70% of the control in dimethylthiazol carboxymethoxy-phenyl sulfophenyl tetrazolium (MTS) assays and were discarded. The hit compounds were then validated by secondary screening, which determined the antiviral activities of each compound serially diluted at concentrations ranging from 0.1 μM to 30 μM under Huh7/Rep-Feo cells cultured in an identical manner to the primary screen. Compounds inhibiting replication with a 50% effective concentration (EC50) of <5 μM and a selectivity index (SI) of >5 were selected for further analysis.

MTS assay.

To evaluate cell viability, MTS assays were performed using the CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer's directions.

Calculation of the EC50, CC50, and SI.

The EC50 indicates the concentration of test compound that inhibits replicon-based luciferase activity by 50%. The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) indicates the concentration that inhibits cell viability by 50%. The EC50 and CC50 values were calculated using probit regression analysis (2, 26). The selectivity index was calculated by dividing the CC50 by the EC50.

Reporter and expression plasmids.

The plasmid pC1neo-Rluc-IRES-Fluc was constructed to analyze the HCV internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-mediated translation efficiency (19). The plasmid expressed a bicistronic mRNA containing the Renilla luciferase gene translated in a cap-dependent manner, and firefly luciferase was translated by HCV-IRES-mediated initiation. The plasmid pISRE-TA-Luc (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) expressed the firefly luciferase reporter gene under the control of the interferon stimulation response element (ISRE). The plasmid pNF-κB-TA-Luc (Clontech Laboratories, Franklin Lakes, NJ) expressed the firefly luciferase reporter gene under the control of NF-κB. The plasmid pRL-CMV (Promega, Madison, WI), which expressed the Renilla luciferase gene under the control of the cytomegalovirus early promoter/enhancer, was used as a control for the transfection efficiency of pISRE-TA-Luc and pNF-κB-TA-Luc (8).

Western blot analysis.

Fifteen micrograms of total cell lysates was separated using NuPage 4-to-12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) and blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Each membrane was incubated with primary antibodies followed by a peroxidase-labeled anti-IgG antibody and visualized by chemiluminescence reaction using the ECL Western Blotting Analysis System (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). The primary antibodies were anti-NS5A (BioDesign, Saco, ME), anti-HCV core (kindly provided by T. Wakita), anti-phospho-p65 (Ser536) (93H1; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), anti-IκBα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and anti-β-actin (Sigma) antibodies.

HCV-JFH1 virus cell culture.

HCV-JFH1 RNA transcribed in vitro was transfected into Huh7.5.1 cells. The transfected cells were subcultured every 3 to 5 days. The culture supernatant was subsequently transferred onto Huh7.5.1 cells.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis.

The protocols and primers for real-time RT-PCR analysis of HCV RNA have been described previously (17). Briefly, total cellular RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), reverse transcribed, and subjected to real-time RT-PCR analysis. Expression of mRNA was quantified using the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and the ABI 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems).

Analyses of drug synergism.

The effects on HCV replication of antiviral hit compounds plus IFN-α or BILN 2061 were analyzed according to classical isobologram analyses (24, 28). Dose-inhibition curves for IFN or BILN 2061 and the test compounds were drawn, with the 2 drugs (IFN or BILN 2061 and each test compound) used alone or in combination. For each drug combination, the concentrations of IFN or BILN 2061 and test compound that inhibited HCV replication by 50% (EC50s) were plotted against the fractional concentration of IFN or BILN 2061 and the compound on the x and y axes, respectively. A theoretical line of additivity was drawn between plots of the EC50s obtained for either drug used alone. The combined effects of the 2 drugs were considered to be additive, synergistic, or antagonistic if the plots of the combined drugs were located on, below, or above the line of additivity, respectively.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed using Welch's t test. P values of less than 0.01 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Screening results.

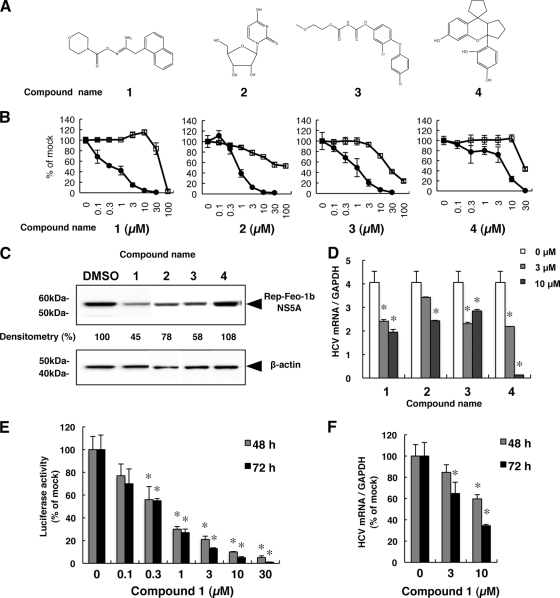

To identify novel regulators of HCV replication, 4,004 chemical compounds were screened using the Huh7/Rep-Feo replicon assay system. The primary screens identified 117 compounds that inhibited ≥50% of replicon luciferase activity at 5 μM. Of the 117 compounds, 74 were cytotoxic and could not be further evaluated. In the secondary screen, nontoxic primary hits were evaluated by determining the antiviral activities of serial dilutions at concentrations ranging from 0.1 μM to 30 μM. This screen identified 19 compounds with EC50s of less than 5 μM and CC50 values 5-fold greater than the EC50 values. The effect of each secondary hit on HCV-NS5A protein expression was examined using Western blot analysis. Of the 19 compounds, 4 compounds, designated 1, 2, 3, and 4, suppressed HCV subgenomic replication, with EC50s ranging from 0.36 to 4.81 μM and SIs ranging from 5.64 to more than 100 (Table 1 and Fig. 1A and B; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). By Western blot analysis, compounds 1, 2, and 3 decreased HCV-NS5A protein levels at concentrations of 5 μM after incubation for 48 h (Fig. 1C). Compared with compounds 1, 2, and 3, the effect of compound 4 on HCV-NS5A protein expression was not remarkable at a concentration of 5 μM, similar to the results from the luciferase assay shown in Fig. 1B. The effects of the compounds on the HCV replicon were further validated in the JFH-1 cell culture. As shown in Fig. 1D, compounds 1, 2, 3, and 4 significantly inhibited intracellular RNA replication of HCV-JFH1. Although compound 4 was negative by Western blot analysis, it decreased HCV replication in the other assays, including the replicon and HCV-JFH1 virus assays. Thus, we concluded that compound 4 was an antiviral hit. These results indicated that the 4 compounds identified by cell-based screening suppressed subgenomic HCV replication and HCV replication in an HCV-based cell culture.

Table 1.

Effects of the leading hit compounds on HCV replicationa

| Compound | EC50 (μM) | CC50 (μM) | SI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.36 (0.22–0.58) | 45.2 (35.9–56.9) | 126 |

| 2 | 0.86 (0.73–1.02) | >100 | >116 |

| 3 | 0.94 (0.76–1.06) | 25.3 (19.8–32.3) | 26.9 |

| 4 | 4.81 (3.79–6.12) | 27.1 (17.1–58.0) | 5.64 |

The EC50 and CC50 values are reported, with 95% confidence intervals in parentheses, from a representative experiment performed in triplicate.

Fig 1.

Effects of 4 screening hit compounds on HCV replication. (A) Chemical structures of hit compounds. (B) Huh7/Rep-Feo cells were treated with the indicated concentration of each compound for 48 h. Luciferase activities representing HCV replication are shown as percentages of the DMSO-treated control luciferase activity (solid circles). Cell viability is shown as a percentage of control viability (open squares). Each point represents the mean of triplicate data points, with the standard deviations represented as error bars. (C) Huh7/Rep-Feo cells were treated with DMSO or compounds 1 through 4 at 5 μM for 48 h, and Western blotting was performed using anti-HCV NS5A and anti-β-actin antibodies. Densitometry of NS5A protein was performed, and the results are indicated as percentages of the DMSO-treated control. The assay was repeated three times, and a representative result is shown. (D) Huh7.5.1 cells were transfected with HCV-JFH1 RNA and cultured in the presence of the indicated compounds at 3 μM or 10 μM. At 72 h after transfection, the cellular expression levels of HCV-RNA were quantified by real-time RT-PCR. The bars indicate means and SD. (E) Time-dependent reduction of luciferase activities in Huh7/Rep-Feo cells induced by compound 1. Luciferase activities are shown as percentages of the DMSO-treated control luciferase activity. The bars indicate means and SD. (F) Time-dependent reduction of cellular expression levels of HCV-RNA in HCV-JFH1-transfected cells induced by compound 1. HCV RNA levels are shown as percentages of the DMSO-treated control HCV-RNA level. The bars indicate means and SD. The asterisks indicate P values of less than 0.01.

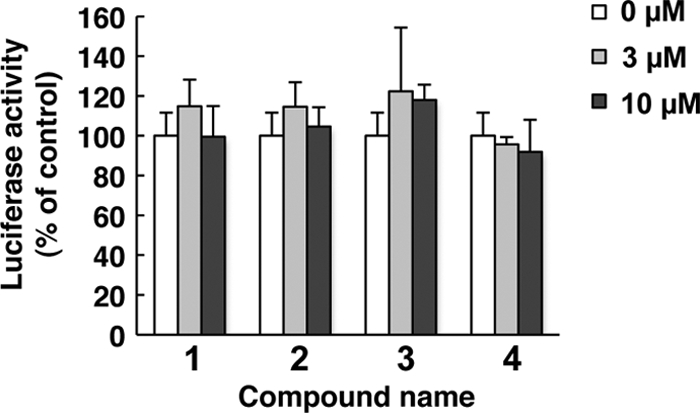

Hit compounds did not suppress HCV IRES-mediated translation.

To determine whether the leading antiviral hits suppressed HCV IRES-dependent translation, we used the Huh7 cell line that had been stably transfected with pCIneo-Rluc IRES-Fluc. Treatment of these cells with the test compounds did not result in significant change in the internal luciferase activities at compound concentrations that suppressed expression of the HCV replicon (Fig. 2), suggesting that the effect of the hit compounds on HCV replication does not involve suppression of IRES-mediated viral-protein synthesis.

Fig 2.

Hit compounds do not affect HCV IRES-mediated translation. The bicistronic reporter plasmid pC1neo-Rluc-IRES-Fluc was transfected into Huh7 cells. The cells were cultured in the presence of the indicated concentrations of compounds 1 through 4. After 6 h of treatment, luciferase activities were measured, and the values were normalized against Renilla luciferase activities. The assays were performed in triplicate. The bars indicate means and SD.

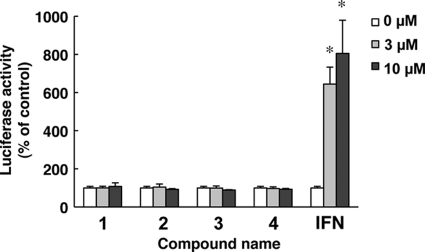

Hit compounds do not activate interferon-stimulated gene responses.

To study whether the actions of the hit compounds involved IFN-mediated antiviral signaling that would induce expression of an IFN-stimulated gene, an ISRE-luciferase reporter plasmid, pISRE-TA-Luc, was transfected into Huh7 cells, and the transfected cells were cultured in the presence of the 4 compounds at concentrations of 0, 3, or 10 μM. In contrast to interferon, which elevated ISRE promoter activities significantly, the hit compounds showed no effects on the ISRE-luciferase activities (Fig. 3). These results indicated that the action of the hit compounds is independent of interferon signaling.

Fig 3.

Hit compounds do not activate interferon-stimulated gene responses. Plasmids pISRE-TA-Luc and pRL-CMV were cotransfected into Huh7 cells. The transfected cells were cultured in the presence of the indicated concentrations of the hit compounds. After 6 h of treatment, luciferase activities were measured, and the values were normalized against Renilla luciferase activities. As positive controls, cells were treated with IFN-α at a concentration of 0, 3, or 10 U/ml. The bars indicate means and SD. The asterisks indicate P values of less than 0.01.

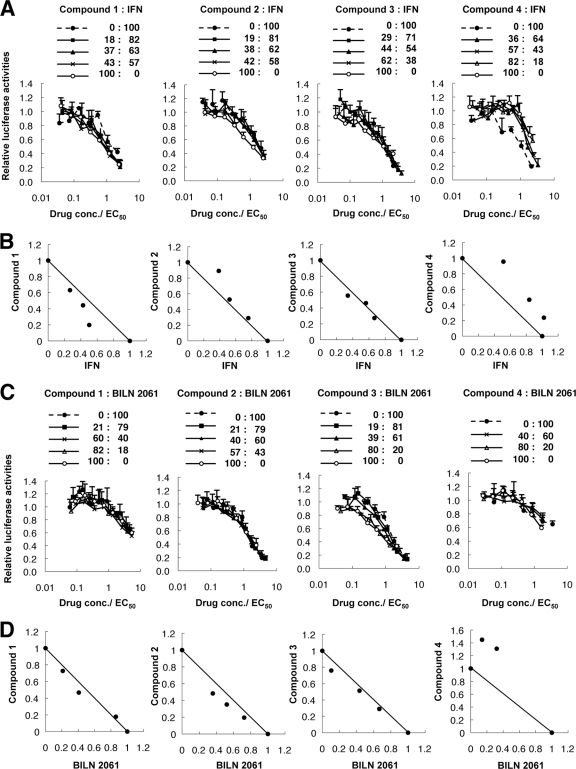

Drug synergism with IFN-α or BILN 2061.

To investigate whether the hit compounds were synergistic with IFN-α or the protease inhibitor BILN 2061, we used isobologram analyses (24, 28). HCV replicon cells were treated with a combination of IFN-α or BILN 2061 and each hit compound at an EC50 ratio of 1:0. 4:1, 3:2, 2:3, 1:4, or 0:1, and the dose-effect results were plotted (Fig. 4A and C). The fractional EC50s for IFN-α or BILN 2061 and each compound were plotted on the x and y axes, respectively, to generate an isobologram. As shown in Fig. 4B, all plots of the fractional EC50s of compound 1 and IFN-α fell below the line of additivity, while the plots were located closed to the line of additivity for the treatments using IFN-α plus compound 2 or 3 and above the line for the treatment using IFN-α plus compound 4. Those results indicated that the anti-HCV effect of compound 1 was synergistic with IFN-α, the anti-HCV effects of compounds 2 and 3 were additive, and the effect of compound 4 was antagonistic. In the BILN 2061 combination study, the combination with compound 2 was slightly synergistic, while the combination with compound 1 or 3 was additive, and the combination with compound 4 was antagonistic (Fig. 4D).

Fig 4.

Drug synergism analyses: effects of each of the 4 antiviral hit compounds combined with IFN-α or BILN 2061 on HCV replication. (A and C) Huh7/Rep-Feo cells were cultured with a combination of IFN-α or BILN 2061 and antiviral hit compound 1, 2, 3, or 4 at the indicated ratios, adjusted by the EC50 of the individual drug. The internal luciferase activities were measured after 48 h of culture. Assays were performed in triplicate. Shown are means and SD. (B and D) Graphical presentations of isobologram analyses. For each drug combination in panels A and C, the EC50s of IFN-α or BILN 2061 and compound 1, 2, 3, or 4 for inhibition of HCV replication were plotted against the fractional concentrations of IFN-α or BILN 2061 and each compound, as indicated on the x and y axis, respectively. A theoretical line of additivity is drawn between the EC50s for each drug alone.

SARs of compound 1 and similar compounds.

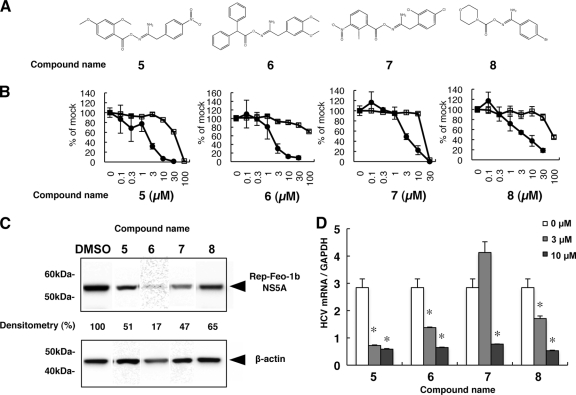

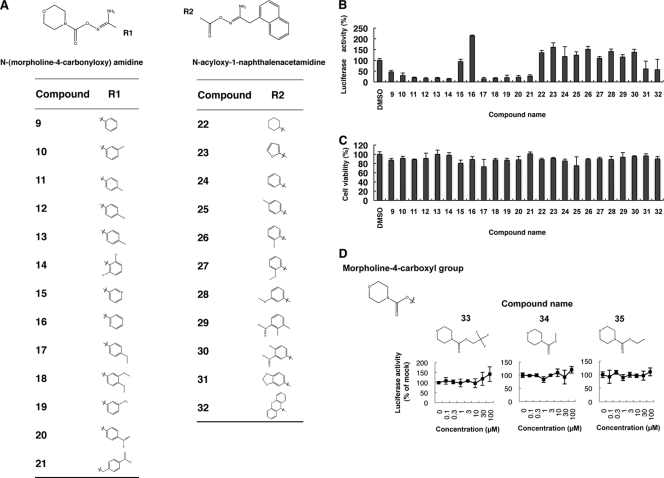

We next conducted SAR analyses for hit compound 1 by screening 69 compounds with structures similar to that of compound 1 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Out of those compounds, we identified 4 structural analogues that suppressed subgenomic HCV replication with EC50s ranging from 1.82 to 4.03 μM and SIs of 6.01 through >43.7 (Table 2 and Fig. 5A and B). Similarly, the 4 compounds designated 5, 6, 7, and 8 substantially decreased HCV-NS5A protein expression levels following treatment with the compounds (Fig. 5C). Consistent with the replicon results, the compounds significantly suppressed HCV-JFH1 mRNA in cell culture (Fig. 5D). Although the suppressive activities of the 4 compounds were similar, the original compound 1 showed the greatest anti-HCV activity. Therefore, we conducted SAR analyses of the compound 1 N-(morpholine-4-carbonyloxy) amidine and N-acyloxy-1-naphthalenacetamidine moieties. We screened 13 compounds containing N-(morpholine-4-carbonyloxy) amidine and 11 with N-acyloxy-1-naphthalenacetamidine (Fig. 6A; see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Intriguingly, 11 out of the 13 N-(morpholine-4-carbonyloxy) amidine compounds suppressed the subgenomic HCV replicon without cytotoxicity at a fixed concentration of 5 μM. In contrast, only 2 N-acyloxy-1-naphthalenacetamidine compounds decreased HCV replication (Fig. 6B and C). We also conducted dose-dependent suppression assays for HCV replicon. As shown in Table 3, 11 out of 13 N-(morpholine-4-carbonyloxy) amidine compounds consistently decreased subgenomic HCV replication, with EC50s ranging from 1.52 through 8.62 μM and SIs of 14.2 to >61.4. Of these 11 compounds, compound 14 was the most potent, with an EC50 of 1.63 μM and an SI of >61.4. The antiviral effect of compound 14 against HCV-JFH1 was identical to that of the original compound 1. To identify the moiety conferring anti-HCV activity, we tested the morpholine-4-carboxyl moiety within the N-(morpholine-4-carboynloxy) amidine structure (Fig. 6D). Three compounds bearing the morpholine-4-carboxyl moiety were tested, and none showed suppressive activity toward the HCV replicon. These results suggested that the entire N-(morpholine-4-carbonyloxy) amidine moiety was important for efficient anti-HCV activity.

Table 2.

Effects of derivative compounds of 1 on HCV replicationa

| Compound | EC50 (μM) | CC50 (μM) | SI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 1.82 (0.58–5.68) | 45.1 (14.3–52.5) | 24.8 |

| 6 | 2.29 (1.57–3.34) | >100 | >43.7 |

| 7 | 2.83 (1.43–5.78) | 17.0 (5.25–38.7) | 6.01 |

| 8 | 4.03 (3.51–4.63) | 87.8 (59.1–172) | 21.8 |

The EC50 and CC50 values are reported, with 95% confidence intervals in parentheses, from a representative experiment performed in triplicate.

Fig 5.

Effects of derivatives of compound 1 on HCV replication. (A) Chemical structures of screening hits of compound 1 derivatives. (B) Huh7/Rep-Feo cells were treated with various concentrations of each compound for 48 h. Luciferase activity for HCV RNA replication is shown as a percentage of the DMSO-treated control luciferase activity (solid circles). Cell viability is also shown as a percentage of control viability (open squares). Each point represents the mean of triplicate data points, with standard deviations represented as error bars. (C) HCV NS5A protein expression levels in Huh7/Rep-Feo cells after treatment with the hit compounds. Huh7/Rep-Feo cells were treated with DMSO and derivative compounds at 5 μM for 48 h, and Western blotting was performed using anti-HCV NS5A and anti-β-actin antibodies. Densitometry of the NS5A protein was performed, and the results are indicated as percentages of the DMSO-treated control. The assay was repeated three times, and a representative result is shown. (D) Huh7.5.1 cells were transfected with HCV-JFH1 RNA and cultured in the presence of the indicated compounds at a concentration of 3 μM or 10 μM. At 72 h after transfection, total cellular RNA was extracted, followed by real-time RT-PCR. The bars indicate means and SD. The asterisks indicate P values of less than 0.01. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Fig 6.

SARs of derivatives of compound 1 that contain N-(morpholine-4-carbonyloxy) amidine or N-acyloxy-1-naphthalenacetamidine moieties. (A) Chemical structures of compounds with N-(morpholine-4-carbonyloxy) amidine or N-acyloxy-1-naphthalenacetamidine analyzed for SARs. (B) Huh7/Rep-Feo cells were cultured in the presence of 13 compounds with N-(morpholine-4-carbonyloxy) amidine and 11 compounds with N-acyloxy-1-naphthalenacetamidine at a fixed concentration of 5 μM. The internal luciferase activities were measured after 48 h of culture. Luciferase activity for HCV RNA replication levels is shown as a percentage of the drug-negative (DMSO) control. Assays were performed in triplicate. The bars indicate means and SDs. (C) Cell viability is shown as a percentage of control viability. Assays were performed in triplicate. The bars indicate means and SD. (D) Effects of morpholine-4-carboxyl compounds on HCV replication. Huh7/Rep-Feo cells were treated with various concentrations of compound 33, 34, or 35 for 48 h. Luciferase activity for HCV RNA replication levels is shown as a percentage of the drug-negative (DMSO) control. Each point represents the mean of triplicate data points, with standard deviations represented as error bars.

Table 3.

Effects of N-(morpholine-4-carbonyloxy) amidine compounds on HCV replicationa

| Compound | EC50 (μM) | CC50 (μM) | SI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 8.62 (7.03–10.6) | >100 | >11.1 |

| 10 | 3.32 (2.28–4.84) | 47.0 (15.7–76.4) | 14.2 |

| 11 | 1.55 (1.04–2.30) | 48.8 (12.8–95.6) | 31.5 |

| 12 | 1.52 (1.14–2.02) | 51.0 (16.2–96.7) | 33.6 |

| 13 | 1.60 (1.36–1.88) | 38.6 (29.4–50.7) | 24.1 |

| 14 | 1.63 (1.34–2.00) | >100 | >61.4 |

| 15 | ND | ND | ND |

| 16 | ND | ND | ND |

| 17 | 1.77 (1.39–2.26) | 63.3 (21.8–128) | 35.8 |

| 18 | 3.80 (2.48–5.83) | 100 (86.8–138) | 26.3 |

| 19 | 1.99 (1.59–2.48) | 55.1 (14.8–105) | 27.7 |

| 20 | 2.61 (1.68–4.05) | >100 | >38.3 |

| 21 | 1.55 (1.45–1.67) | 94.6 (93.0–98.0) | 61.0 |

The EC50 and CC50 values are reported, with 95% confidence intervals in parentheses, from a representative experiment performed in triplicate. ND, not determined.

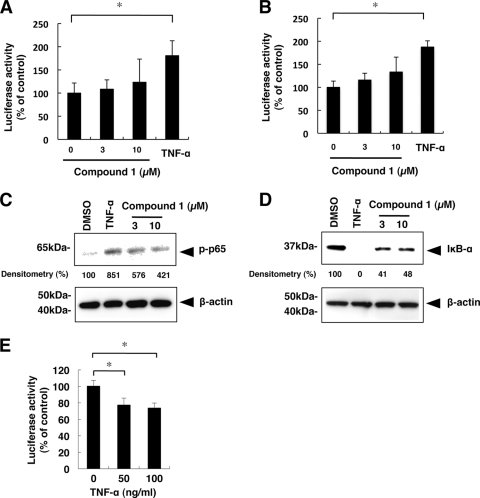

Effect of compound 1 on the NF-κB signaling pathway.

NF-κB, composed of homo- and heterodimeric complexes of Rel-like domain-containing proteins, including p50 and p65, is a key regulator of innate and adaptive immune responses through transcriptional activation of several antiviral proteins (9, 23). We performed luciferase reporter assays, a p65 phosphorylation assay, and an IκB-α degradation assay to assess the effect of compound 1 on NF-κB signaling in host cells. Intriguingly, treatment of both Huh7 cells and HCV replicon-expressing cells with compound 1 increased NF-κB reporter activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7A and B). Consistently, treatment with compound 1 increased phosphorylated NF-κB p65 in Huh7 cells (Fig. 7C). Activation of NF-κB involves degradation of a suppressor protein, IκB-α. As shown in Fig. 7D, IκB-α protein levels were strongly decreased in cells treated with compound 1. Additionally, activation of the NF-κB pathway by TNF-α treatment significantly suppressed HCV replication (Fig. 7E). These results indicated that the antiviral action of compound 1 partially involved activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway.

Fig 7.

Effects of compound 1 on the NF-κB signaling pathway. (A and B) NF-κB-responsive luciferase reporter assays. The plasmids pNF-κB-TA-Fluc and pRL-CMV were cotransfected into Huh7 cells (A) or HCV replicon-expressing cells (B). At 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with compound 1 at a concentration of 0, 3, or 10 μM. After 6 h, luciferase activities were measured, and the values were normalized against Renilla luciferase activities. As a positive control, cells were treated with TNF-α (50 ng/ml). Assays were performed in triplicate. The bars indicate means and SD. (C and D) Huh7 cells were treated for 30 min with compound 1 at concentrations of 3 and 10 μM, and Western blot analyses of phosphorylated p65 and IκBα were conducted. As a positive control, cells were treated with TNF-α (50 ng/ml). β-Actin served as a loading control. Densitometry of phosphorylated p65 protein and IκB-α protein was performed, and the results are indicated as percentages of the DMSO-treated control. The assay was repeated three times, and a representative result is shown. (E) Effect of activation of NF-κB signaling on HCV RNA replication. Huh7/Rep-Feo cells were treated with TNF-α at a concentration of 0, 50, or 100 ng/ml for 48 h. Luciferase activity for HCV RNA replication levels is shown as a percentage of untreated negative-control luciferase activity. Assays were performed in replicates of 6. The asterisks indicate P values of less than 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Using a chimeric luciferase reporter-based subgenomic HCV-Feo replicon assay and an HCV-JFH1 cell culture, we discovered 4 novel anti-HCV compounds from cell-based screening of a library of 4,004 chemicals (Fig. 1 and Table 1). These compounds displayed anti-HCV activity at noncytotoxic concentrations. The most potent of the leading hit compounds was MCNA, and SAR analyses revealed that 4 compounds with structures similar to that of MCNA also had antiviral activity (Fig. 5). Furthermore, we showed that the N-(morpholine-4-carbonyloxy) amidine moiety within the structure of MCNA is essential for antiviral activity (Fig. 6).

After the development of the HCV replicon system, the study of HCV replication and discovery of novel anti-HCV agents have shown great progress. To date, our group and others have already made several successful attempts to discover novel inhibitors of HCV replication. Using Huh7/Rep-Feo cells, we previously identified novel anti-HCV substances, including cyclosporins (18, 19), short interfering RNA (siRNA) (31), hydroxyl-methyl-glutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (10), and epoxide compounds (20). Huh7/Rep-Feo cells were also used for screening a whole-genome siRNA library and successfully identified human genes that support HCV replication (27). Although the HCV replicon system cannot screen for inhibitors of viral entry and release, it is still a useful tool for rapid, reliable, and reproducible high-throughput screening. In our study, we used library sets of compounds that had probably not been used for anti-HCV drug screening before.

The morpholine moiety is a common pharmacophore present in many biosynthetic compounds, such as antimycotic agents (4, 21), and inhibitors of phosphoinositide 3-kinases (5, 16, 30), TNF-α-converting enzymes (14), and matrix metalloproteinases (1). Among the antimycotic morpholine derivatives, amorolfine has been widely used to treat onychomycosis (4, 21). The morpholino oxygen in a synthetic phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor, LY294002, participated directly in a key hydrogen-bonding interaction at the ATP-binding site of phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ (30). Although the morpholine moieties are key components of many inhibitors, anti-HCV morpholine compounds have not yet been reported. In this report, we demonstrated for the first time that a morpholine-bearing compound, N-(morpholine-4-carbonyloxy) amidine, had a potent antiviral effect on HCV replication.

Among the 4 hit compounds, MCNA activated the NF-κB pathway (Fig. 7A, B, C, and D). NF-κB is a central regulator of innate and adaptive immune responses. NF-κB-induced transcription is induced in response to a variety of signals, including proinflammatory cytokines, stress induction, and by-products of microbial and viral infection (9). In HCV-infected cells, activation of transcription factors, such as NF-κB and many interferon regulatory factors, proceeds mainly through Toll-like receptors and RIG-I-dependent host signaling pathways triggered by double-stranded RNA products (3). NF-κB, interferon regulatory factor 1, and interferon regulatory factor 3 bind to the positive regulatory domains of the IFN-β promoter to induce IFN-β expression and elicit antiviral states in host cells (23). Therefore, we hypothesized that the augmentation of host antiviral response through NF-κB activation is an important strategy for anti-HCV treatment. Our demonstration that the activation of NF-κB signaling suppressed HCV replication appears to follow this strategy (Fig. 7E). In support of the idea, Toll-like receptor 7 agonist has shown anti-HCV effects in a preclinical study (7). The anti-HCV activities of MCNA cannot be explained solely by NF-κB activation, because its antiviral activity was much more potent than selective NF-κB activation by TNF-α treatment (Fig. 7E). There remains the possibility that MCNA has a direct viral target. It will be important to assess whether long-term exposure to the compounds could select resistant variants. Although other mechanisms may underlie the antiviral activity, we hypothesize that one of the antiviral mechanisms of MCNA is NF-κB activation that is independent of IFN signaling.

Although several DAAs are currently in advanced clinical trials and the recently approved telaprevir and boceprevir combination therapies achieved high sustained virologic response rates, the frequent emergence of drug-resistant viruses is a major weakness of such agents. An ongoing search for more potent and less toxic antiviral agents to improve anti-HCV chemotherapeutics is necessary. Our results indicate that MCNA and related N-(morpholine-4-carbonyloxy) amidine compounds constitute a new class of anti-HCV agents. Additional investigations elucidating their mechanism of action, and future modifications to improve anti-HCV activity, may open a new anti-HCV therapeutic window.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Frank Chisari for providing Huh7.5.1 cells, Takaji Wakita for providing the plasmid pJFH1full, and the Chemical Biology Screening Center of Tokyo Medical and Dental University for their assistance in this work.

This study was supported in part by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan; the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare; the Japan Health Sciences Foundation; and the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation.

We declare that we have nothing to disclose regarding funding from industries or conflicts of interest with respect to the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 December 2011

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aac.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Almstead NG, et al. 1999. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of potent thiazine- and thiazepine-based matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 42:4547–4562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bailey M, Williams NA, Wilson AD, Stokes CR. 1992. PROBIT: weighted probit regression analysis for estimation of biological activity. J. Immunol. Methods 153:261–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bigger CB, et al. 2004. Intrahepatic gene expression during chronic hepatitis C virus infection in chimpanzees. J. Virol. 78:13779–13792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Flagothier C, Piérard-Franchimont C, Piérard GE. 2005. New insights into the effect of amorolfine nail lacquer. Mycoses 48:91–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hickson I, et al. 2004. Identification and characterization of a novel and specific inhibitor of the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated kinase ATM. Cancer Res. 64:9152–9159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoofnagle JH, Seeff LB. 2006. Peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. N. Engl. J. Med. 355:2444–2451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Horsmans Y, et al. 2005. Isatoribine, an agonist of TLR7, reduces plasma virus concentration in chronic hepatitis C infection. Hepatology 42:724–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kanazawa N, et al. 2004. Regulation of hepatitis C virus replication by interferon regulatory factor 1. J. Virol. 78:9713–9720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Karin M, Lin A. 2002. NF-kappaB at the crossroads of life and death. Nat. Immunol. 3:221–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim SS, et al. 2007. A cell-based, high-throughput screen for small molecule regulators of hepatitis C virus replication. Gastroenterology 132:311–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kwo PY, et al. 2010. Efficacy of boceprevir, an NS3 protease inhibitor, in combination with peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C infection (SPRINT-1): an open-label, randomised, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet 376:705–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kwong AD, Kauffman RS, Hurter P, Mueller P. 2011. Discovery and development of telaprevir: an NS3-4A protease inhibitor for treating genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus. Nat. Biotechnol. 29:993–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lauer GM, Walker BD. 2001. Hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:41–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levin JI, et al. 2005. Acetylenic TACE inhibitors. Part 2: SAR of six-membered cyclic sulfonamide hydroxamates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 15:4345–4349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. 2001. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 46:3–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Menear KA, et al. 2009. Identification and optimisation of novel and selective small molecular weight kinase inhibitors of mTOR. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19:5898–5901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mishima K, et al. 2010. Cell culture and in vivo analyses of cytopathic hepatitis C virus mutants. Virology 405:361–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nakagawa M, et al. 2004. Specific inhibition of hepatitis C virus replication by cyclosporin A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 313:42–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nakagawa M, et al. 2005. Suppression of hepatitis C virus replication by cyclosporin A is mediated by blockade of cyclophilins. Gastroenterology 129:1031–1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peng LF, et al. 2007. Identification of novel epoxide inhibitors of hepatitis C virus replication using a high-throughput screen. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3756–3759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Polak A, Jäckel A, Noack A, Kappe R. 2004. Agar sublimation test for the in vitro determination of the antifungal activity of morpholine derivatives. Mycoses 47:184–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Poordad F, et al. 2011. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 364:1195–1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Randall RE, Goodbourn S. 2008. Interferons and viruses: an interplay between induction, signalling, antiviral responses and virus countermeasures. J. Gen. Virol. 89:1–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sakamoto N, et al. 2007. Bone morphogenetic protein-7 and interferon-alpha synergistically suppress hepatitis C virus replicon. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 357:467–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sarrazin C, Zeuzem S. 2010. Resistance to direct antiviral agents in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology 138:447–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Soothill JS, Ward R, Girling AJ. 1992. The IC50: an exactly defined measure of antibiotic sensitivity. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 29:137–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tai AW, et al. 2009. A functional genomic screen identifies cellular cofactors of hepatitis C virus replication. Cell Host Microbe 5:298–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tanabe Y, et al. 2004. Synergistic inhibition of intracellular hepatitis C virus replication by combination of ribavirin and interferon-alpha. J. Infect. Dis. 189:1129–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wakita T, et al. 2005. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat. Med. 11:791–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Walker EH, et al. 2000. Structural determinants of phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibition by wortmannin, LY294002, quercetin, myricetin, and staurosporine. Mol. Cell 6:909–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yokota T, et al. 2003. Inhibition of intracellular hepatitis C virus replication by synthetic and vector-derived small interfering RNAs. EMBO Rep. 4:602–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhong J, et al. 2005. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:9294–9299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.