Abstract

Campylobacter jejuni is a major zoonotic pathogen transmitted to humans via the food chain and is prevalent in chickens, a natural reservoir for this pathogenic organism. Due to the importance of macrolide antibiotics in clinical therapy of human campylobacteriosis, development of macrolide resistance in Campylobacter has become a concern for public health. To facilitate the control of macrolide-resistant Campylobacter, it is necessary to understand if macrolide resistance affects the fitness and transmission of Campylobacter in its natural host. In this study we conducted pairwise competitions and comingling experiments in chickens using clonally related and isogenic C. jejuni strains, which are either susceptible or resistant to erythromycin (Ery). In every competition pair, Ery-resistant (Eryr) Campylobacter was consistently outcompeted by the Ery-susceptible (Erys) strain. In the comingling experiments, Eryr Campylobacter failed to transmit to chickens precolonized by Erys Campylobacter, while isogenic Erys Campylobacter was able to transmit to and establish dominance in chickens precolonized by Eryr Campylobacter. The fitness disadvantage was linked to the resistance-conferring mutations in the 23S rRNA. These findings clearly indicate that acquisition of macrolide resistance impairs the fitness and transmission of Campylobacter in chickens, suggesting that the prevalence of macrolide-resistant C. jejuni will likely decrease in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure.

INTRODUCTION

Campylobacter jejuni has been recognized as one of the most common causes of human enterocolitis worldwide (2). This organism is transmitted to humans via contaminated foods of animal origin, especially undercooked poultry meat and unpasteurized milk/dairy products (2, 4). Although antibiotic treatment may not be necessary for most food-borne campylobacteriosis cases, antimicrobial therapy is warranted in patients with severe or prolonged infections (2, 12). Generally, erythromycin (Ery) and ciprofloxacin are considered the main antimicrobials for treating human campylobacteriosis (2, 12, 17). However, during the past decades Campylobacter has become increasingly resistant to clinically important antimicrobial agents, compromising the effectiveness of clinical therapy (17). Since antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter can be transmitted from food animals to humans through the food chain, the rising resistance to antibiotics among Campylobacter isolates of animal origin is a concern for public health.

Ery, a 14-membered ring macrolide, as well as other 15- and 16-membered ring macrolides (e.g., azithromycin, tilmicosin, and tylosin), are of high efficacy against several important pathogens, including Campylobacter, Chlamydia, and Mycobacterium species (20, 21). These antimicrobials inhibit bacterial protein synthesis by binding to the 50S subunits of bacterial ribosome and have been widely used for the treatment of infections in both humans and animals for a number of years (20). The use of macrolides in food-producing animals is considered to be one of the major factors influencing the emergence of Ery-resistant (Eryr) Campylobacter (20). There are recent evidence indicating that the continuous use of a macrolide at subtherapeutic level in chickens results in the development of Ery resistance in Campylobacter (32, 34).

Although multiple mechanisms of macrolide resistance have been reported in different bacterial genus and species, modifications of the ribosomal target sites (e.g., the 23S rRNA gene and ribosomal proteins L4 and L22) and active efflux via the CmeABC efflux pump are the major mechanisms conferring macrolide resistance in Campylobacter (13, 19, 20, 41). To date, point mutations in domain V of the 23S rRNA gene at positions 2074 and 2075, corresponding to positions 2058 and 2059 in Escherichia coli, respectively, have been recognized as the most common mechanism for macrolide resistance in C. jejuni and Campylobacter coli (20, 41). Among the reported resistance-associated mutations, the A2074C, A2074G, and A2075G mutations are found to confer a high-level of macrolide resistance, while other mutations in the 23S rRNA gene or the mutations in the ribosomal proteins L4 (G74D) and L22 (insertions at position 86 or 98) are shown to confer a lower level of macrolide resistance in Campylobacter (13, 14, 19, 20, 41).

In bacteria, the acquisition of antibiotic resistance, particularly the resistance mediated by chromosomal mutations, is frequently accompanied by a biological cost, resulting in a decrease in fitness (i.e., a reduced growth rate or a decrease in ability to compete and persist in the host and environment) of microorganisms in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure (7–9, 30, 33, 40). Even though many types of antibiotic resistance impose a biological cost on bacterial fitness, the fitness cost can be reduced at different levels through compensatory mutations (5, 10, 11, 33, 40). In addition, some resistance-conferring mutations or determinants do not incur an apparent fitness burden or even enhance the fitness of the antibiotic resistant strains (10, 26, 31, 37, 38, 44). For example, a modeling study on antibiotic resistance revealed that some resistant bacteria, such as penicillin-resistant strains, did not show a decreased fitness in the host; instead, these resistant strains possessed an increased ability to transmit between hosts compared to the susceptible strains (6). In C. jejuni, it has been found that fluoroquinolone (FQ)-resistant strains, carrying the C257T mutation in the gyrA gene, do not show a fitness cost in its natural host (chicken). Instead, the FQ-resistant mutants possess an enhanced fitness in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure (26).

Although macrolide resistance mechanisms were well defined in Campylobacter, the impact of the resistance-associated mutations on Campylobacter fitness has not been well defined. Recently, it was shown that acquisition of Ery resistance imposes a fitness burden in C. jejuni in culture medium as Eryr Campylobacter showed a competitive disadvantage compared to erythromycin-susceptible (Erys) Campylobacter in mixed cultures (25, 27). However, the fitness changes observed in laboratory media may not necessarily reflect the fitness alteration in vivo since the environments in animals are much more complex than in culture media (6, 11). More importantly, to facilitate the control of macrolide resistance in Campylobacter, it is essential to assess whether the resistance impacts Campylobacter fitness and transmissibility in its natural hosts. Toward this end, we used clonally related and isogenic mutants of Eryr Campylobacter to evaluate their fitness and transmissibility in chickens, the major animal reservoir for C. jejuni.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

C. jejuni strains used in the present study are listed in Table 1. C. jejuni ATCC 700819 (NCTC 11168), Bd34-2, and Bd41-3 are susceptible to Ery, whereas the other strains (J.L.270, J.L.272, J.L.273, T.L.101, T.L.102, or T.L.103) exhibit low or high resistance to Ery (Table 1). The isolates Bd34-2, Bd41-3, J.L.270, J.L.272, and J.L.273 are clonally related to ATCC 700819 and were isolated from chickens that were originally challenged with the parent strain ATCC 700819 and treated with tylosin-containing feed as described in a previous study (34). Briefly, the chickens were inoculated in laboratory with C. jejuni ATCC 700819 at 3 days of age and provided with the medicated feed (tylosin; 50 mg/kg of feed) for the entire 41 days of the experiment. C. jejuni was reisolated from the inoculated chickens from cloacal swabs at different days after the inoculation. Detailed information on the experiment is described in the previous publication (34). The isogenic Eryr transformants T.L.101, T.L.102, and T.L.103 were constructed from the parent strain ATCC 700819 using natural transformation (see below). These transformants have either A2074G or A2075G mutation in the 23S rRNA gene and are highly resistant to Ery (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Campylobacter strains used in this study

| Straina | Description | Ery MIC (μg/ml)b | Mutation in 23S rRNAc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erys strains | |||

| ATCC 700819 | Highly motile variant of C. jejuni NCTC 11168 | 2 | None |

| Bd34-2* | Erys isolate from a chicken inoculated with 700819 and treated with tylosin-containing feed | 2 | None |

| Bd41-3* | Erys isolate from a chicken inoculated with 700819 and treated with tylosin-containing feed | 2 | None |

| Clonally related Eryr strains | |||

| J.L.270* | Eryr isolate from a chicken inoculated with 700819 and treated with tylosin-containing feed | 32 | None |

| J.L.272* | Eryr isolate from a chicken inoculated with 700819 and treated with tylosin-containing feed | >512 | A2074G |

| J.L.273* | Eryr isolate from a chicken inoculated with 700819 and treated with tylosin-containing feed | >512 | A2074G |

| Isogenic Eryr strains | |||

| T.L.101† | Laboratory-constructed Eryr transformant from 700819 | >512 | A2074G |

| T.L.102† | Laboratory-constructed Eryr transformant from 700819 | >512 | A2075G |

| T.L.103† | Laboratory-constructed Eryr transformant from 700819 | >512 | A2075G |

*, Clonally related to 700819 and the dose of tylosin in the feed was 50 mg/kg of feed (34); †, transformants were from three independent transformation experiments.

Determined by the agar dilution method.

Corresponding to the nucleotide positions in the 23S rRNA gene of C. jejuni NCTC 11168.

Construction of the Eryr transformants.

To construct the isogenic Eryr transformants, C. jejuni strains with the A2074G mutation (J.L.273) or A2075G mutation (C.T.2–2) were used to prepare donor genomic DNA for natural transformation. These Eryr Campylobacter strains were originally isolated from chickens and turkeys (34, 36). Genomic DNA from the Eryr strains was extracted using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's protocol and then digested with the restriction enzyme EcoRV prior to the natural transformation experiment. This digestion was done to release the 23S rRNA gene from its flanking sequences in the donor DNA, allowing the selection of transformants that only contain mutations in the 23S rRNA gene and minimizing the cotransfer of unrelated mutations from the donor DNA to the transformants. Natural transformation was performed with a biphasic method as described by Wang and Taylor (45) using the parent strain ATCC 700819 as the recipient. Transformants were selected on Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar containing 8 μg of Ery/ml, and the A2074G or A2075G mutation in the 23S rRNA gene of the isogenic Eryr transformants was confirmed by sequence analysis. 23S rRNA gene-specific primers (5′-GTAAACGGCGGCCGTAACTA-3′ and 5′-GACCGAACTGTCTCACGACG-3′) were used to amplify an internal part of the domain V of the 23S rRNA gene (29). PCR amplification was performed with an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 52°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 40 s, and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. The amplified PCR products (714 bp) were purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) prior to sequencing. DNA sequencing was conducted at the DNA facility of Iowa State University. Three transformants (T.L.101, T.L.102, and T.L.103) derived from three independent transformation experiments were used in the present study (Table 1).

Motility assay.

Erys and Eryr Campylobacter strains were tested for their motility prior to inoculation into chickens. Briefly, Erys and Eryr Campylobacter strains grown overnight were resuspended in MH broth and adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.3. Each Campylobacter strain was inoculated to the center of semisolid MH motility media (0.4% MH agar) using a sterile needle. After incubation at 42°C for 48 h under microaerobic conditions, the diameter of swarming from the inoculation spot was measured in millimeters and recorded.

In vitro growth determination.

To determine the in vitro growth of the parent strain ATCC 700819, clonally related Eryr strains, and isogenic Eryr transformants, a fresh culture of each Campylobacter strain was inoculated into MH broth and adjusted to an initial cell density of 105 CFU/ml. The cultures were incubated at 42°C with shaking (160 rpm) for 30 h under microaerobic conditions. The growth kinetics was determined by measuring the numbers of Campylobacter colonies (log10 CFU/ml) at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 24, and 30 h postinoculation.

Pairwise competition experiments.

Newly hatched broiler chickens from a commercial hatchery were used to determine the in vivo competition between Eryr and Erys Campylobacter in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure. The chickens used in the present study were tested negative for Campylobacter by culturing cloacal swabs before use. These birds were randomly assigned to groups with 10 to 15 birds per group. Each group was inoculated with either a single or a mixture of Eryr and Erys Campylobacter at 1:1 ratio via oral gavage. The Campylobacter strains used for chicken inoculation were grown at 42°C for 24 h under microaerobic conditions. The inoculum was given to the birds at 3 days of age with approximately 107 CFU per bird. Fecal samples were collected from each bird by means of cloacal swabs at 3, 6, and 10 days postinoculation (dpi). Each fecal sample was serially diluted in MH broth and plated onto MH agar containing Campylobacter selective agents and growth supplements (SR084E and SR117E; Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) to recover the total Campylobacter colonies and onto MH agar containing the same selective agents and growth supplements plus 8 μg of Ery/ml to recover Eryr Campylobacter colonies. Colony count was performed after 48 h of incubation at 42°C under microaerobic conditions. The results of the differential plating were further confirmed by the MIC of selected isolates by the agar dilution method.

Transmission of Eryr Campylobacter in chickens.

Three groups of newly hatched broiler chickens (11 to 13 birds per group) were used to assess the transmissibility of Eryr Campylobacter between hosts. Each group of chickens was inoculated with a single Campylobacter strain (107 CFU per bird) via oral gavage. The strains used in this experiment included the Erys parent strain ATCC 700819, the isogenic Eryr transformants T.L.101 (carrying the A2074G mutation) and T.L.102 (carrying the A2075G mutation). At 5 dpi, when the colonization was established similarly in each group by the corresponding strain, eight chickens inoculated with the Erys strain and four chickens inoculated with the Eryr strain T.L.101 were randomly selected and mingled together (2:1 ratio between chickens inoculated with Erys and Eryr Campylobacter, respectively). Likewise, 11 chickens inoculated with the Eryr strain T.L.102 were mingled with 5 chickens originally inoculated with the Erys Campylobacter strain, giving an approximately 1:2 ratio between chickens inoculated with Erys and Eryr Campylobacter strains. The chickens (n = 8) inoculated with the Eryr Campylobacter strain T.L.101 that were not used for comingling studies were raised separately and served as a control for determining the in vivo stability of Eryr Campylobacter in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure. Fecal samples were collected from each bird before comingling, as well as at 7 and 14 days after comingling, using cloacal swabs. The number of Erys and Eryr Campylobacter colonies was determined using the differential plating method on both MH agar and MH agar containing 8 μg of Ery/ml as described earlier. The agar dilution method was also performed to confirm the results of the differential plating.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test.

The MICs of Ery for Campylobacter colonies randomly selected at each sampling time point were determined using the agar dilution method as recommended by the CLSI (16). C. jejuni 33560 was used as the quality control organism, and the MIC of Ery at 8 μg/ml was used as the resistance breakpoint in the present study. Ery was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO.

Statistical analysis.

The significance of differences between Erys and Eryr Campylobacter in colonization levels at each sampling time point was determined by using Student's t test, Welch's t test to allow for nonconstant variation across treatment groups, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to allow for non-normality as described previously (24). Differences were considered significant at a P value of <0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Eryr Campylobacter.

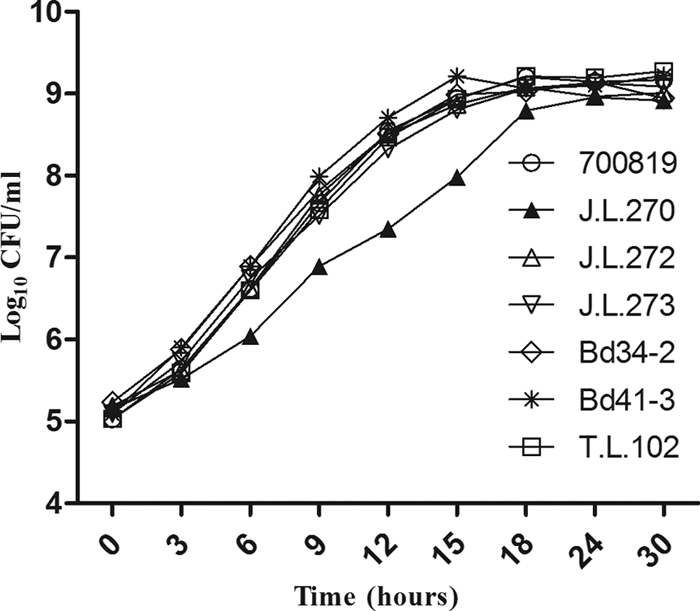

The clonally related Eryr strains (except J.L.270) and isogenic Eryr transformants carried either A2074G or A2075G mutation in all three copies of the 23S rRNA gene (Table 1). Although no specific point mutation was observed in the 23S rRNA gene of J.L.270, this Eryr strain carried a mutation in the ribosomal protein L4 (G74D). Since motility is a key factor influencing the ability of Campylobacter to colonize the chicken intestinal tract (18, 23, 28, 39), the motility of Eryr and Erys Campylobacter strains used in the present study was investigated. The Eryr and Erys strains were equally motile under the laboratory conditions used here (data not shown). Compared to the Erys strains, the Eryr isolates did not show apparent differences in growth kinetics in MH broth except for J.L.270, which grew slower than the rest of strains (Fig. 1). The Eryr strains harboring either the A2074G or the A2075G mutation in the 23S rRNA gene were highly resistant to erythromycin (MICs > 512 μg/ml), while J.L.270, which carried the G74D point mutations in the L4 protein, had an Ery MIC of 32 μg/ml (Table 1). All of the Erys isolates had an Ery MIC of 2 μg/ml (Table 1).

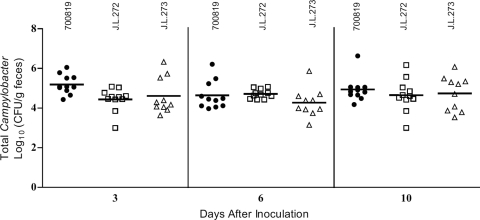

Fig 1.

In vitro growth kinetics of clonally related and isogenic C. jejuni strains. The cultures were incubated in MH broth at 42°C under microaerobic conditions with shaking (160 rpm). Each data point represents the mean log10 CFU/ml of five technical replicates. The experiment was repeated twice and similar results were obtained. 700819, Bd34-2, and Bd41-3 are Ery susceptible, while J.L. 270, J.L.272, J.L.273, and T.L.102 are Ery resistant (see Table 1 for MIC values).

In vivo competition between clonally related isolates.

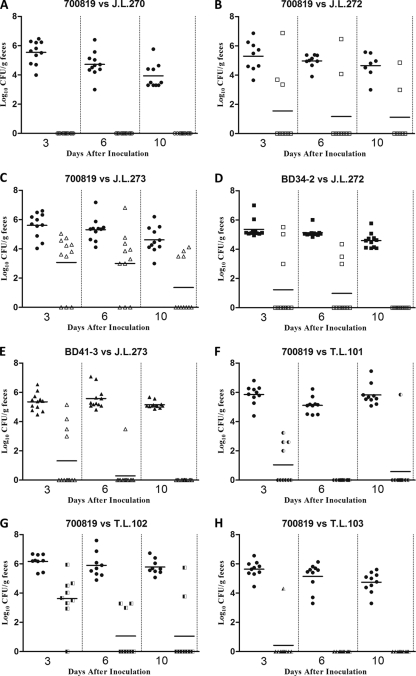

To determine whether the acquisition of macrolide resistance affects the fitness of Campylobacter in its natural host, we conducted pairwise competition experiments in chickens using clonally related strains of C. jejuni. When the Erys C. jejuni ATCC 700819 strain and its clonally related Eryr strains were individually inoculated into chickens, both Erys and Eryr strains were able to colonize the chicken intestinal tract effectively at similar levels (Fig. 2). However, when these Erys and Eryr Campylobacter were concomitantly inoculated into chickens, Erys strain outcompeted Eryr strains as early as dpi 3 (Fig. 3A, B, and C). For example, when Erys C. jejuni ATCC 700819 and Eryr strain J.L.270 were coinoculated into chickens, only C. jejuni ATCC 700819 was detected in the chicken intestinal tract throughout the 10-day study period (Fig. 3A). Similarly, when Erys C. jejuni ATCC 700819 and Eryr strain J.L.272 were coinoculated into chickens, the majority of the birds were colonized only by the Erys strain, and the Eryr Campylobacter was clearly outcompeted by the Erys strains (Fig. 3B). Although Eryr strain J.L.273 was detected in the majority of the chickens after coinoculated with Erys Campylobacter, it was outnumbered by 700819 and was cleared from 7 of the 11 inoculated chickens (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that Eryr C. jejuni is less fit than Erys C. jejuni in chickens in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure.

Fig 2.

Colonization levels of Erys C. jejuni ATCC 700819 (●) and clonally related Eryr strains J.L.272 (□) and J.L.273 (△) in chickens. Each Campylobacter strain was individually inoculated into chickens at the concentration of 1.4 × 106 CFU/bird (ATCC 700819), 5.56 × 105 CFU/bird (J.L.272), and 2.57 × 105 CFU/bird (J.L.273). Fecal samples were collected at 3, 6, and 10 days after inoculation. Each data point represents the number of Campylobacter obtained from an individual chicken. The mean colonization level (log10 CFU/g feces) of each group is indicated by a horizontal bar.

Fig 3.

Pairwise competition between Erys and Eryr Campylobacter in chickens in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure. (A to E) Competition between clonally related isolates. (A) ATCC 700819 (●) versus J.L.270 (○); (B) ATCC 700819 (●) versus J.L.272 (□); (C) ATCC 700819 (●) versus J.L.273 (△); (D) Bd34-2 (■) versus J.L.272 (□); (E) Bd41-3 (▲) versus J.L.273 (△). (F to H) Competition between isogenic strains. (F) ATCC 700819 (●) versus T.L.101 (◐); (G) ATCC 700819 (●) versus T.L.102 (◧); (H) ATCC 700819 (●) versus T.L.103 (◭). Each symbol represents the number of Erys or Eryr Campylobacter in an individual chicken. The horizontal bars represent the mean colonization levels (log10 CFU/g feces) of Erys or Eryr strains detected at each sampling time point.

To confirm the fitness burden observed in Eryr C. jejuni, two additional pairwise competition experiments using clonally related Erys and Eryr C. jejuni derived from experimentally challenged chickens (Bd34-2 versus J.L.272 and Bd41-3 versus J.L.273) were conducted. Remarkably, similar results were observed in both pairwise competition experiments, in which Eryr C. jejuni was outcompeted by Erys C. jejuni as early as dpi 3, and no Eryr C. jejuni was detected in feces collected at dpi 10 from both pairwise competition groups (Fig. 3D and E). The predominance of Erys Campylobacter in the coinoculated chickens was further confirmed by MIC testing of randomly selected Campylobacter colonies. The agar dilution test showed that 95.30% (162 of 170) of the tested Campylobacter colonies were susceptible to Ery (Table 2), confirming the results of the differential plating. Together, these findings demonstrated that Erys C. jejuni is more fit than clonally related Eryr C. jejuni in chickens in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure.

Table 2.

MICs of randomly selected C. jejuni colonies from the competition experiments

| Pairwise competition | No. of isolates with an Ery MIC (μg/ml)a of: |

No. of Erys and Eryr isolatesb at: |

Total no. of isolates (%) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dpi 3 |

dpi 6 |

dpi 10 |

|||||||||||

| 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | ≥4 | Erys | Eryr | Erys | Eryr | Erys | Eryr | Erys | Eryr | |

| Clonally related pairs | |||||||||||||

| 700819/J.L.270 | 0 | 1 | 23 | 9 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 33 (100.0) | 0 (0) |

| 700819/J.L.272 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 7 | 4* | 7 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 22 (84.6) | 4 (15.4) |

| 700819/J.L.273 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 8 | 4* | 9 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 29 (87.9) | 4 (12.1) |

| Bd34-2/J.L.272 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 37 (100.0) | 0 (0) |

| Bd41-3/J.L.273 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 29 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 41 (100.0) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 5 | 20 | 58 | 79 | 8 | 50 | 4 | 56 | 2 | 56 | 2 | 162 (95.3) | 8 (4.7) |

| Isogenic pairs | |||||||||||||

| 700819/T.L.101 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 21 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 22 (100.0) | 0 (0) |

| 700819/T.L.102 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 17 (100.0) | 0 (0) |

| 700819/T.L.103 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 16 (100.0) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 2 | 0 | 11 | 42 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 55 (100.0) | 0 (0) |

*, The actual MICs of these isolates were ≥512 μg/ml.

The isolates were randomly selected from plating at 3, 6, and 10 days postinoculation (dpi). The breakpoint for Ery resistance is ≥8 μg/ml.

In vivo competition between isogenic isolates.

To determine whether the fitness cost observed with Eryr C. jejuni was associated with the specific resistance-conferring mutations in the 23S rRNA gene, isogenic Eryr transformants were generated from the Erys parent strain C. jejuni ATCC 700819 and used for pairwise competition experiments. When the Erys parent strain and the isogenic Eryr transformant carrying the A2074G mutation in the 23S rRNA gene (T.L.101) were concomitantly inoculated into chickens, the Erys strain quickly outcompeted T.L.101 (Fig. 3F). Although C. jejuni T.L.101 was isolated from four chickens at dpi 3, none of the samples collected at dpi 6 and only 1 of 10 samples from dpi 10 were positive for this Eryr Campylobacter strain (Fig. 3F). Likewise, when Eryr transformants carrying the A2075G mutation in the 23S rRNA gene (T.L.102 and T.L.103) and the isogenic Erys parent strain ATCC 700819 were coinoculated into chickens, the isogenic Eryr transformants were outcompeted by the Erys parent strain as early as dpi 3 (Fig. 3G and H). Similar to the clonally related C. jejuni strains, the MIC results from the agar dilution method also confirmed the results of the differential plating. All of the 55 tested Campylobacter colonies were susceptible to Ery (Table 2). Together, these findings strongly suggest that the fitness cost observed in Eryr C. jejuni is linked to the specific point mutations in the 23S rRNA gene.

Transmission of Eryr Campylobacter in chickens.

To assess the ability of Eryr Campylobacter to transmit between chickens, we conducted a comingling experiment using three groups of chickens that were precolonized with the Erys parent strain ATCC 700819, the isogenic Eryr transformant T.L.101, or the isogenic Eryr transformant T.L.102. Before comingling, the chickens inoculated with ATCC 700819, T.L.101, or T.L.102 were colonized at similar levels (data not shown). When chickens precolonized with ATCC 700819 (Erys) were mingled with chickens precolonized with T.L.101 (Eryr), no Eryr Campylobacter was detected in the feces of Erys inoculated chickens throughout the study period (Fig. 4A). In contrast, Erys Campylobacter was detected from feces of chickens precolonized with the Eryr strain at both 7 and 14 days after comingling (Fig. 4B). Moreover, Erys C. jejuni totally displaced Eryr Campylobacter in 2 of the 4 Eryr precolonized chickens at 14 days after comingling. Similar results were also observed when chickens precolonized with the Erys parent strain ATCC 700819 were mingled with chickens precolonized with the isogenic Eryr transformant T.L.102. Among 5 chickens originally colonized with Erys Campylobacter, all but one were negative for Eryr Campylobacter at both 7 and 14 days after comingling (Fig. 4C). In contrast, 10 of 11 chickens originally colonized with Eryr Campylobacter were positive for Erys strain at 7 days after comingling. At 14 days after comingling, seven of the 11 chickens precolonized by Eryr Campylobacter were completely replaced by the Erys strain (Fig. 4D). Notably, the number of Eryr Campylobacter in the feces of chickens precolonized with the Eryr strain T.L.102 reduced considerably, whereas the number of Erys Campylobacter rapidly increased after comingling. Together, these results indicate that Eryr Campylobacter is highly impaired in its transmission to chickens with an established Erys Campylobacter population and that it can be readily displaced by sensitive Campylobacter in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure.

Fig 4.

Levels of Campylobacter colonization in chickens before and after comingling. (A) Colonization levels of Campylobacter in chickens (n = 8) precolonized with Erys C. jejuni ATCC 700819 before and after comingling with chickens (n = 4) precolonized with Eryr transformant T.L.101. The numbers of 700819 and T.L.101 in the chickens are indicated by solid circles (●) and open triangles (△), respectively. (B) Colonization levels of Campylobacter in chickens (n = 4) precolonized with Eryr transformant T.L.101 before and after comingling with chickens (n = 8) precolonized with Erys C. jejuni ATCC 700819. The numbers of 700819 and T.L.101 in the chickens are indicated by by solid circles (●) and open triangles (△), respectively. (C) Colonization levels of Campylobacter in chickens (n = 5) precolonized with Erys C. jejuni ATCC 700819 before and after comingling with chickens (n = 11) precolonized with Eryr transformant T.L.102. The numbers of 700819 and T.L.102 in the chickens are indicated by solid circles (●) and open diamonds (♢), respectively. (D) Colonization levels of Campylobacter in chickens (n = 11) precolonized with Eryr transformant T.L.102 before and after comingling with chickens (n = 5) precolonized with Erys C. jejuni ATCC 700819. The numbers of 700819 and T.L.102 in the chickens are indicated by solid circles (●) and open diamonds (♢), respectively. (E) Colonization levels of Eryr strain T.L.101 in chickens (n = 8) in the absence of competing Erys C. jejuni. These non-mingled chickens were used as a control for the comingling study. In panels A to E, each data point represents the log10 transformed CFU number/g of feces from a single bird, and the mean colonization level (log10 CFU/g of feces) is indicated by a horizontal bar.

To confirm the transmission of Erys Campylobacter to Eryr colonized chickens, MIC testing was performed with randomly selected Campylobacter colonies isolated from the comingled chickens. Among Campylobacter colonies collected at 7 and 14 days postmingling, 62.5 and 40.0% of the colonies from chickens originally colonized with T.L.101 and T.L.102, respectively, were susceptible to Ery (Table 3). In contrast, none of the isolates from the chickens precolonized with Erys Campylobacter were resistant to Ery (Table 3). These MIC data further confirmed the transmission of Erys Campylobacter to chickens precolonized by Eryr Campylobacter and the inability of Eryr Campylobacter to spread to chickens with an established Erys Campylobacter population.

Table 3.

MICs of randomly selected C. jejuni colonies from the comingling chickens

| Comingling study (n) | No. of isolates with an Ery MIC (μg/ml)a at: |

No. of Erys and Eryr isolatesb at: |

Total no. of isolates (%) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAM 7 |

DAM 14 |

||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | ≥16 | Erys | Eryr | Erys | Eryr | Erys | Eryr | |

| 700819 and T.L.101 | |||||||||||

| 700819-inoculated birds (8) | 7 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 15 (100.0) | 0 (0) |

| T.L.101-inoculated birds (4) | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) |

| 700819 and T.L.102 | |||||||||||

| 700819-inoculated birds (5) | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 9 (100.0) | 0 (0) |

| T.L.102-inoculated birds (11) | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 8 (40.0) | 12 (60.0) |

| Nonmingling group | |||||||||||

| T.L.101 (8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 8 | 0 (0) | 17 (100.0) |

The tested isolates were randomly collected from chickens at 7 and 14 days after comingling.

DAM, day after comingling. The breakpoint for Ery is ≥8 μg/ml.

Chickens inoculated with the Eryr strain T.L.101 that were not mingled with Erys inoculated chickens were used as a control to assess the phenotypic stability of Eryr Campylobacter in chickens in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure. T.L.101 colonization in the inoculated chickens persisted for the entire experimental period (Fig. 4E). The Ery MICs for the randomly selected Campylobacter colonies were also ≥512 μg/ml (Table 3), indicating that T.L.101 stably maintained the Eryr phenotype in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure. This result suggests that the appearance of Erys Campylobacter in chickens precolonized with Eryr Campylobacter was not due to the reversion of the resistance phenotype.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the ecological fitness of Eryr Campylobacter in chickens in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure by using clonally related and isogenic strains of C. jejuni. The results clearly indicate that acquisition of macrolide resistance entails a fitness cost for C. jejuni in its natural host. From the pairwise competition experiments, it was clear that Eryr Campylobacter was outcompeted rapidly by Erys strains (Fig. 3). In addition, when chickens colonized with Eryr C. jejuni were comingled with birds colonized with Erys C. jejuni, Erys Campylobacter was able to transmit to and colonize in the chickens precolonized by Eryr Campylobacter, while Eryr C. jejuni failed to transmit to the chickens precolonized by Erys Campylobacter (Fig. 4). Together, these findings reveal the fitness burden of Eryr Campylobacter in its natural host in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure.

The use of clonally related and isogenic transformants in the chicken experiments linked the fitness burden to the point mutations in the 23S rRNA gene of Eryr mutants. However, it should be pointed out that natural transformation may not necessarily generate true isogenic mutants since other unrelated mutations might be also transferred to the transformants. To minimize this potential problem, we digested the donor DNA with EcoRV prior to transformation to release the 23S rRNA gene from the rest of the genome. In addition, we used three transformants from three independent transformations for the chicken experiments, all of which yielded the same results (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). Furthermore, the clonally related isolates also consistently showed a significant fitness cost in the Eryr mutants. Collectively, these findings provide strong evidence that links the resistance-conferring mutation in the 23S rRNA to the reduced fitness in chickens.

It has been shown that certain mutations in the 23S rRNA gene, such as the A2074G transition, may have a negative effect on the growth rate of Campylobacter in culture media (19, 25). However, in the present study we found that the growth rates of the Eryr mutants carrying the A2074G or A2075G mutations were similar to that of the Erys wild-type strain (Fig. 1). Similar to our finding, other studies (27, 34) also reported that the Eryr mutants with the A2074G transition or A2074C transversion did not show any growth defect compared to Erys parent strains. Thus, the fitness cost for the Eryr mutants carrying mutations in the 23S rRNA genes is not attributable to a growth defect. In addition, the Eryr mutants colonized at levels similar to the Erys strain when mono-inoculated into chickens (Fig. 2) but colonized at levels significantly lower than the Erys strains when coinoculated into chickens (Fig. 3). These results indicate that the fitness cost was primarily due to the inability of Eryr mutants to compete with Erys C. jejuni. J.L.270, which carried a mutation in the L4 protein (Table 1), grew slower than other strains (Fig. 1), and its resistance phenotype was not stable when assessed by passage in laboratory media (not shown). Thus, the fitness cost of this strain could be explained partly by the growth defect and the instability of its resistance phenotype. In contrast to J.L. 270, other tested Eryr mutants stably maintained Ery resistance in both laboratory media (data not shown) and in chickens (Fig. 2 and Fig. 4E).

The fitness cost of Eryr C. jejuni in its natural hosts revealed in the present study is consistent with results obtained with other model systems. Two studies using in vitro culture systems demonstrated that Eryr C. jejuni was less fit than Erys Campylobacter in mixed cultures (25, 27). In addition, another study showed a fitness cost of macrolide-resistant Campylobacter carrying an A2074C mutation in the colonization of mice (3). These studies using different systems consistently demonstrated the fitness cost of macrolide-resistant Campylobacter. The association between macrolide resistance and a significant burden on bacterial fitness was also observed in other bacteria. When a sequential passage of a mixed culture between macrolide-resistant and macrolide-susceptible Helicobacter pylori was performed, the ratio of the resistant strain to the susceptible strain was considerably reduced per passage (31). It was also shown that clarithromycin resistance confers a fitness cost on H. pylori in mice and the fitness cost was reduced in clinical isolates (9). A recent study demonstrated that azithromycin resistance mutations reduced the virulence and fitness of Chlamydia caviae in guinea pigs (8). The reason for the reduced fitness of macrolide-resistant bacteria is unknown at present, but it is plausible to speculate that the resistance-conferring mutations in bacteria 23S rRNA gene might affect protein synthesis rates. Since macrolide antibiotics are known to inhibit protein synthesis and ribosomal assembly in bacteria (15), mutations that counteract the inhibitory effects of macrolides might alter protein synthesis, leading to a fitness disadvantage in the absence of antibiotic selection.

The comingling experiments revealed an impaired transmission of Eryr Campylobacter to chickens precolonized by Erys C. jejuni (Fig. 4). In contrast, Erys C. jejuni was able to transmit to and establish colonization in chickens that were precolonized by Eryr C. jejuni. In some birds, the Eryr strains were totally replaced by Erys strains after comingling. This finding implies that in the natural reservoir (chickens), where Campylobacter is prevalent, it is likely that Eryr Campylobacter encounters a difficulty in spread among birds in the absence of antibiotic selection. It should be pointed out that the Erys Campylobacter isolated from the chickens previously colonized with a Eryr strain was unlikely the result of the reversion or loss of the A2074G or A2075G mutations in the 23S rRNA gene since these mutations are stable as shown in the chickens colonized with the Eryr Campylobacter only (Fig. 4E) and in other published work (14, 19, 27). The finding from the comingling experiments confirms and complements the results of pairwise competition experiments and indicates that Eryr Campylobacter is less fit than Erys Campylobacter in its natural host.

Our laboratory findings reported here are consistent with the national surveillance data in the United States and Denmark. In the United States, the use of macrolide antimicrobials in animal production has been a practice for years, but the prevalence of Eryr C. jejuni has been at a low level (22). In Denmark, reduced use of tylosin as a growth promoter in swine led to a significant decrease in the number of Eryr C. coli isolated from pigs (1). Based on our laboratory observations using clonally related isolates derived from chickens and the transmission studies (Fig. 2, 3, and 4), we expect that a similar situation (i.e., outcompetition of Eryr C. jejuni by Erys strains) occurs on chicken farms. However, the laboratory findings should be extrapolated to on-farm settings cautiously since many factors influence bacterial fitness. For example, the use of macrolide antimicrobials on farms would provide a selective advantage for Eryr Campylobacter and facilitates the maintenance of the resistant population. In addition, compensatory mutations could occur under prolonged selection, which might reduce the fitness cost associated with Ery resistance. Furthermore, the ecological fitness of C. jejuni can be influenced by other bacterial and environmental factors. Thus, the fitness picture of C. jejuni in animal reservoirs is more complex than that revealed in a laboratory setting and is likely influenced by interactions of many different factors.

The reduced fitness of Eryr Campylobacter is a stark contrast to fluoroquinolone (FQ)-resistant Campylobacter, which can rapidly outcompete FQ-susceptible strains and can be persistently maintained in chickens in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure (37). This difference indicates that different antimicrobial resistance mechanisms have varied effects on the fitness of Campylobacter in animal reservoir. The fitness burden of Eryr Campylobacter in antibiotic-free environments, the low spontaneous mutation rate for macrolide resistance (34), and the slow process of macrolide resistance development (32, 34) may have all contributed to the relatively low prevalence of resistance to macrolide antimicrobials compared to FQ resistance in C. jejuni. Although withdrawal of FQ antimicrobials in the United States has thus far had a limited effect on the prevalence of FQ-resistant Campylobacter in poultry (35, 42, 43), management of macrolide antibiotic usage on farms is likely to be an effective way to reduce the prevalence of macrolide resistance in Campylobacter.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jun Lin at the University of Tennessee for providing some of the Campylobacter strains used in this study.

This study was supported by grant 2005-51110-03273 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture and by National Institutes of Health grant RO1DK063008.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 December 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Aarestrup FM, McDermott PF, Wegener HC. 2008. Transmission of antibiotic resistance from food animals to humans, p 645–665 In Nachamkin I, Szymanski CM, Blaser MJ. (ed), Campylobacter, 3rd ed ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allos BM. 2001. Campylobacter jejuni infections: update on emerging issues and trends. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:1201–1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Almofti YA, Dai M, Sun Y, Haihong H, Yuan Z. 2011. Impact of erythromycin resistance on the virulence properties and fitness of Campylobacter jejuni. Microb. Pathog. 50:336–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Altekruse SF, Tollefson LK. 2003. Human campylobacteriosis: a challenge for the veterinary profession. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 223:445–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Andersson DI. 2003. Persistence of antibiotic resistant bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:452–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Andersson DI, Hughes D. 2010. Antibiotic resistance and its cost: is it possible to reverse resistance? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:260–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Andersson DI, Levin BR. 1999. The biological cost of antibiotic resistance. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:489–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Binet R, Bowlin AK, Maurelli AT, Rank RG. 2010. Impact of azithromycin resistance mutations on the virulence and fitness of Chlamydia caviae in guinea pigs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1094–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bjorkholm B, et al. 2001. Mutation frequency and biological cost of antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:14607–14612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bjorkman J, Hughes D, Andersson DI. 1998. Virulence of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:3949–3953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bjorkman J, Nagaev I, Berg OG, Hughes D, Andersson DI. 2000. Effects of environment on compensatory mutations to ameliorate costs of antibiotic resistance. Science 287:1479–1482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blaser MJ, Engberg J. 2008. Clinical aspects of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli infections, p 99–121 In Nachamkin I, Szymanski CM, Blaser MJ. (ed), Campylobacter, 3rd ed ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cagliero C, Mouline C, Cloeckaert A, Payot S. 2006. Synergy between efflux pump CmeABC and modifications in ribosomal proteins L4 and L22 in conferring macrolide resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3893–3896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Caldwell DB, Wang Y, Lin J. 2008. Development, stability, and molecular mechanisms of macrolide resistance in Campylobacter jejuni. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3947–3954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Champney WS, Burdine R. 1998. Macrolide antibiotic inhibition of translation and 50S ribosomal subunit assembly in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus cells. Microb. Drug Resist. 4:169–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute 2008. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk and dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria isolated from animals; approved standard M31–A3, 3rd ed Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 17. Engberg J, Aarestrup FM, Taylor DE, Gerner-Smidt P, Nachamkin I. 2001. Quinolone and macrolide resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli: resistance mechanisms and trends in human isolates. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:24–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fernando U, Biswas D, Allan B, Willson P, Potter AA. 2007. Influence of Campylobacter jejuni fliA, rpoN, and flgK genes on colonization of the chicken gut. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 118:194–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gibreel A, et al. 2005. Macrolide resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli: molecular mechanism and stability of the resistance phenotype. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2753–2759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gibreel A, Taylor DE. 2006. Macrolide resistance in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:243–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Giguere S. 2006. Macrolides, azalides, and ketolides, p 191–205 In Giguere S, et al. (ed), Antimicrobial therapy in veterinary medicine, 4th ed Blackwell Publishing Professional, Ames, IA [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gilbert JM, White DG, McDermott PF. 2007. The US national antimicrobial resistance monitoring system. Future Microbiol. 2:493–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guerry P. 2007. Campylobacter flagella: not just for motility. Trends Microbiol. 15:456–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guo B, et al. 2008. CmeR functions as a pleiotropic regulator and is required for optimal colonization of Campylobacter jejuni in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 190:1879–1890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Han F, Pu S, Wang F, Meng J, Ge B. 2009. Fitness cost of macrolide resistance in Campylobacter jejuni. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 34:462–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Han J, Sahin O, Barton YW, Zhang Q. 2008. Key role of Mfd in the development of fluoroquinolone resistance in Campylobacter jejuni. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hao H, et al. 2009. 23S rRNA mutation A2074C conferring high-level macrolide resistance and fitness cost in Campylobacter jejuni. Microb. Drug Resist. 15:239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hendrixson DR. 2008. Regulation of flagellar gene expression and assembly, p 545–558 In Nachamkin I, Szymanski CM, Blaser MJ. (ed), Campylobacter, 3rd ed ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jensen LB, Aarestrup FM. 2001. Macrolide resistance in Campylobacter coli of animal origin in Denmark. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:371–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Johnsen PJ, Simonsen GS, Olsvik O, Midtvedt T, Sundsfjord A. 2002. Stability, persistence, and evolution of plasmid-encoded VanA glycopeptide resistance in enterococci in the absence of antibiotic selection in vitro and in gnotobiotic mice. Microb. Drug Resist. 8:161–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kanai K, Shibayama K, Suzuki S, Wachino J, Arakawa Y. 2004. Growth competition of macrolide-resistant and -susceptible Helicobacter pylori strains. Microbiol. Immunol. 48:977–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ladely SR, et al. 2007. Development of macrolide-resistant Campylobacter in broilers administered subtherapeutic or therapeutic concentrations of tylosin. J. Food Prot. 70:1945–1951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Levin BR, Perrot V, Walker N. 2000. Compensatory mutations, antibiotic resistance and the population genetics of adaptive evolution in bacteria. Genetics 154:985–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lin J, et al. 2007. Effect of macrolide usage on emergence of erythromycin-resistant Campylobacter isolates in chickens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1678–1686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Luangtongkum T, et al. 2009. Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter: emergence, transmission and persistence. Future Microbiol. 4:189–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Luangtongkum T, et al. 2006. Effect of conventional and organic production practices on the prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter spp. in poultry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3600–3607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Luo N, et al. 2005. Enhanced in vivo fitness of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter jejuni in the absence of antibiotic selection pressure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:541–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Michon A, et al. 2011. Plasmidic qnrA3 enhances Escherichia coli fitness in absence of antibiotic exposure. PLoS One 6:e24552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nachamkin I, Yang XH, Stern NJ. 1993. Role of Campylobacter jejuni flagella as colonization factors for three-day-old chicks: analysis with flagellar mutants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1269–1273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nagaev I, Bjorkman J, Andersson DI, Hughes D. 2001. Biological cost and compensatory evolution in fusidic acid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 40:433–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Payot S, et al. 2006. Mechanisms of fluoroquinolone and macrolide resistance in Campylobacter spp. Microbes Infect. 8:1967–1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pedersen K, Wedderkopp A. 2003. Resistance to quinolones in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli from Danish broilers at farm level. J. Appl. Microbiol. 94:111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Price LB, Lackey LG, Vailes R, Silbergeld E. 2007. The persistence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter in poultry production. Environ. Health Perspect. 115:1035–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sander P, et al. 2002. Fitness cost of chromosomal drug resistance-conferring mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1204–1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang Y, Taylor DE. 1990. Natural transformation in Campylobacter species. J. Bacteriol. 172:949–955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]