Abstract

The fungal pathogen Candida albicans switches from a yeast-like to a filamentous mode of growth in response to a variety of environmental conditions. We examined the morphogenetic behavior of C. albicans yeast cells lacking the BCY1 gene, which encodes the regulatory subunit of protein kinase A. We cloned the BCY1 gene and generated a bcy1 tpk2 double mutant strain because a homozygous bcy1 mutant in a wild-type genetic background could not be obtained. In the bcy1 tpk2 mutant, protein kinase A activity (due to the presence of the TPK1 gene) was cyclic AMP independent, indicating that the cells harbored an unregulated phosphotransferase activity. This mutant has constitutive protein kinase A activity and displayed a defective germinative phenotype in N-acetylglucosamine and in serum-containing medium. The subcellular localization of a Tpk1-green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion protein was examined in wild-type, tpk2 null, and bcy1 tpk2 double mutant strains. The fusion protein was observed to be predominantly nuclear in wild-type and tpk2 strains. This was not the case in the bcy1 tpk2 double mutant, where it appeared dispersed throughout the cell. Coimmunoprecipitation of Bcy1p with the Tpk1-GFP fusion protein demonstrated the interaction of these proteins inside the cell. These results suggest that one of the roles of Bcy1p is to tether the protein kinase A catalytic subunit to the nucleus.

Candida albicans is an opportunistic human fungal pathogen of great medical significance in immunocompromised patients (25). This fungus has the capability of switching its mode of growth between budding yeast and hypha or pseudohypha in response to environmental signals. Genetic evidence indicates that the morphogenetic switch to the hyphal mode of growth, though associated with pathogenicity and virulence (20), is necessary but not sufficient to trigger disease (5). The relationship between morphology and pathogenicity has been the focus of intensive research devoted to the study of the developmental programs involved in the dimorphic transition.

The remarkable conservation of signal transduction pathways in fungi allowed the identification of components of these pathways in several fungal species based on the insight gained from studying pseudohyphal differentiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In C. albicans, two major pathways implicated in dimorphism could be established: the mitogen-activated protein kinase and the cyclic AMP (cAMP)/protein kinase A transduction pathways (for a review, see reference 19).

Initial biochemical studies indicate that high cAMP levels promote the yeast-to-hypha transition in C. albicans (23, 31). In addition, we have shown that in vivo inhibition of protein kinase A blocks hyphal growth induced by N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) (6). Recent genetic studies allowed the identification of the genes involved in the cAMP/protein kinase A pathway. A transduction cascade similar to that of S. cerevisiae, with regard to location and function of the homologous components, has been established. Thus, CaRas1p, the homologue of the RAS2 product in S. cerevisiae, conveys signals to both the mitogen-activated protein kinase and the cAMP/protein kinase A signaling pathways (18). Downstream of CaRAS1 are the gene for adenylyl cyclase, CDC35 (21), and the two genes encoding the protein kinase A catalytic subunits, TPK1 (3) and TPK2 (37).

The BCY1 gene characterized in this paper encodes the sole protein kinase A regulatory subunit. Transcription factor Efg1p appears to be the last component of the cascade which, upon phosphorylation by protein kinase A, regulates genes related to cAMP-dependent morphogenesis (2). It has been established that both protein kinase A isoforms (Tpk1p and Tpk2p) act positively in the morphogenetic process, although invasiveness on solid medium, a characteristic of infective hyphal growth, specifically requires Tpk2p (3). A recent report indicates that the activity of Cdc35p is also necessary for the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade (29). This result places adenylyl cyclase as a prevalent key regulatory component controlling the mode of growth of the fungus.

We have previously demonstrated that both protein kinase A isoforms are expressed in a C. albicans wild-type strain. Deletion of both TPK2 alleles resulted in a 90% decrease in protein kinase A activity and a diminished ability to germinate in GlcNAc inducing medium. Moreover, germination was blocked by protein kinase A-specific inhibitors and enhanced by activators of the enzyme (7). These results provide biochemical evidence about the positive role of Tpk1p and Tpk2p in the morphogenetic switch and indicate that higher levels of protein kinase A correlate with higher germinative capability.

In this work, we examined the morphogenetic behavior of C. albicans yeast cells lacking the protein kinase A regulatory subunit. We cloned the BCY1 gene and generated a bcy1 tpk2 double mutant strain. All efforts to construct a homozygous bcy1 mutant in a wild-type genetic background were unsuccessful. The protein kinase A activity in the bcy1 tpk2 mutant was independent of the presence of cAMP, indicating that the cell harbored an unregulated phosphotransferase activity. Unexpectedly, this mutant, having a constitutively active protein kinase A, displayed a nongerminative phenotype in GlcNAc- and in serum-containing medium. We found that in a wild-type strain and in the tpk2 null mutant, Tpk1p was predominantly nuclear, whereas in the absence of Bcy1p (bcy1 tpk2 double mutant) it appeared dispersed throughout the cell. The possible role of Bcy1p in tethering the protein kinase A catalytic subunits in the nucleus and its putative relationship with morphogenesis are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Reagents were purchased as follows: kemptide (LRRASLG), cAMP, ATP, anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) and anti-mouse IgG (both conjugated to alkaline phosphatase), protein A immobilized to Sepharose, and protease inhibitors, Sigma Chemical Co.; phosphocellulose paper p-81, Whatman; polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon-P), Millipore Corp.; monoclonal anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP), Clontech; and [γ-32P]ATP and [α-32P]dCTP, New England Nuclear. Oligonucleotides were obtained from either Gibco-BRL or the Service de Synthèse et d'Analyse de l'Université Laval (Canada). All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Strains, media, and growth conditions.

Escherichia coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with 80 μg of ampicillin per ml for plasmid selection or 20 μg of chloramphenicol per ml for fosmid selection. C. albicans strains used in this study, listed in Table 1, were cultured at 30°C in YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose). Strains auxotrophic for uracil were grown in YPD medium supplemented with 50 μg of uridine per ml. Strains carrying the Tpk1-GFP fusion protein were grown on solid or liquid SD medium lacking uridine (35). The PCK1 promoter was induced in SCAA medium (37).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| C. albicans strains | ||

| CAI4 | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434 | 11 |

| H2D | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434 Δtpk2::cat/Δtpk2::cat | 7 |

| bcy1 tpk2 | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434 Δtpk2::cat/Δtpk2::cat bcy1/bcy1 | This study |

| ASM1 | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434 TPK1/TPK1-GFP-URA3 | This study |

| ASM2 | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434 Δtpk2::cat/Δtpk2::cat TPK1/TPK1-GFP-URA3 | This study |

| ASM3 | ura3::λimm434/ura3::λimm434 Δtpk2::cat/Δtpk2::cat bcy1/bcy1 TPK1/TPK1-GFP-URA3 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBI-1 | PCK1 promoter in URA3-marked CARS2 vector | J. F. Emst |

| pLS4 | PCK1 promoter controlling a His-tagged TPK2 in pRC2312 | E. Setiadi J. F. Ernst |

Germ tube induction.

Germ tube formation experiments were performed essentially as described previously (6) except that an MnCl2/imidazole incubation medium was used (34). Cells from the stationary phase of growth were washed twice with distilled water and resuspended in the incubation medium to a final density of 2 × 106 cells/ml. Horse serum or GlcNAc was added to the induction medium to reach a final concentration of 10% or 10 mM, respectively. Incubations were performed as previously described (6).

DNA manipulations and analyses.

All DNA manipulations were carried out with standard protocols (32). Plasmid and fosmid DNA purifications were performed with Qiagen affinity columns following the manufacturer's recommendations. Deletions for DNA sequencing were obtained with the double-stranded nested deletion kit from Pharmacia. DNA sequencing was primarily done by the dideoxy chain termination method with [α-32P]dCTP. Some sequence portions were obtained by automated sequencing performed by the Service de Synthèse et d'Analyse de l'Université Laval (Canada). Southern hybridization analyses were performed with the nonradioactive labeling and detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim) on polyvinylidene difluoride membranes.

Isolation of clones encoding the PKA-R gene.

Two oligonucleotides (5′-GAATTGGCGTTGATGTA-3′ and 5′-GCIACTTCICCIAA[A/G]TA-3′, where I is inosine) were used to amplify a portion of the BCY1 gene from C. albicans strain ATCC 32354. PCR was performed with total genomic DNA and Taq polymerase (35 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 30 s at 72°C, followed by a 5-min incubation at 72°C). The amplicon was cloned in pCR-Script SK(+) (Stratagene) and used as a probe to screen the fosmid library maintained at the University of Minnesota.

Deletion of the C. albicans BCY1 gene.

Deletion of BCY1 alleles was achieved with the Ura-blasting procedure (12). Plasmids pMP1 and pMP3 were used to generate the deletions. pMP1 was constructed as follows. Clone 53, containing a 7.4-kb EcoRV fragment, was used to PCR amplify regions located downstream and upstream from the BCY1 open reading frame. The amplicon obtained with primers 5′-GTGGTACCCAACTGCTGGTCATT-3′ and −48M13 Reverse was cut with KpnI, and the 2.6-kb fragment was cloned in the KpnI site of vector pCUC (carrying the cat-URA3-cat cassette), yielding pCUK. The amplicon generated with primers 5′-CTGGTCGACGTTGTAAAACGACGG-3′ and 5′-GGGCATGCTGGTAAAGATGTTGATTG-3′ was digested with SphI and cloned in the corresponding site of pCUK, giving rise to pMP1.

A 1.0-kb PinAI-EcoRI fragment from the BCY1 locus was cloned into pSVSport1 (Gibco-BRL) and recovered as a PstI-EcoRI fragment that was cloned into pUC19 with the same restriction sites. This construction was digested with StyI, and the ends were filled in and blunt-end ligated to a 1.4-kb XbaI-ScaI fragment (encoding the C. albicans URA3 gene) from pMK22 that had also had its ends filled in, giving pMP3. Strain CAI4 was transformed to uracil prototrophy with these constructs. Transformations were performed with the alkali cation yeast transformation kit (Bio 101) following the manufacturer's recommendations.

Resistance to 5-fluoroorotic acid determined spontaneous loss of the cat-URA3-cat cassette. Loss of the URA3 gene was confirmed by Southern analysis with the URA3 gene of pCUC as a probe.

Construction of the Tpk1-GFP fusion protein.

For construction of the Tpk1-GFP fusion protein, the method developed by Gerami-Nejad et al. (13) was used. Briefly, this method uses PCR primers with 5′ ends corresponding to the desired target gene sequences and 3′ ends that direct amplification of the GFP gene along with the selectable marker URA3. The amplified DNA was transformed directly into C. albicans, and recombinants carrying the inserted marker at the locus of interest were identified.

PCRs were performed with 0.1 μg of pGFP-URA3 as the template, 0.6 μM each primers 5′-GATTTGGATTATGGTATAAGTGGAGTTGAAGACCCATATCGTGATCAATTCCAGGACTTTGGTGGTGGTTCTAAAGGTGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGCTCCTTCCCTTGTTTAAGACTCACCAAGTTTAATTGGCCAAGACTAAAACGGTACTAATCTAGAAGGACCACCTTTGATTG-3′ (reverse), 3.5 mM MgCl2, 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer, 0.4 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 4 U of a 2:1 mixture of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega) and Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs). The 50-μl reactions were run for 4 min at 94°C, then for 25 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 3 min at 72°C, followed by 10 min at 72°C.

The products from 10 PCRs were pooled, precipitated with ethanol, resuspended in 50 μl of water, and used to transform C. albicans CAI4, the tpk2 null mutant (H2D), and the bcy1 tpk2 null mutant strains (42). Transformants were selected on SD medium minus uridine (35). Identification of transformants carrying the correctly integrated cassette was performed by PCR on total genomic DNA with a primer that annealed within the transformation module (5′-CCACCACCAACCAAGAGCCA-3′) and a second primer annealing to the 3′ region located outside the module (5′-CACACCAGGCATGCAATTCG-3′).

Crude extract preparation and protein kinase A activity measurement.

Yeast cells (1 × 107 to 2 × 107) in stationary phase were suspended in 500 μl of 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) containing 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 μg of leupeptin per ml, 20 μg of antipain per ml, 20 μg of pepstatin per ml, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Glass beads were added to the suspension, and cells were disrupted by seven 1-min periods of vortexing, each interrupted by a 1-min interval on an ice bath. The resulting suspension was spun down in a microcentrifuge at maximum speed for 30 min, and the supernatant was used immediately for enzymatic assays.

Protein kinase A activity was measured as previously described (44). Briefly, phosphotransferase activity assays were performed in a final volume of 60 μl containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mM kemptide, 0.1 mM [γ-32P]ATP (0.1 to 0.5 Ci/mmol), and 10 μM cAMP when required. After incubation for 10 min at 30°C, 50-μl aliquots were spotted on phosphocellulose paper squares and dropped into 75 mM phosphoric acid for washing (30).

Western blot analysis.

Proteins from crude extracts or from immunoprecipitates (see below) were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (17) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes by semidry electroblotting. The blots were stained reversibly with Ponceau S, blocked with 5% nonfat dried milk, and incubated overnight with anti-C. albicans Bcy1p antiserum (44) or with a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody. Antibodies bound to the membrane were detected with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG conjugated to alkaline phosphatase.

Immunoprecipitation.

Yeast cells from strains CAI4, H2D, tpk2 bcy1, ASM1, ASM2, and ASM3 were cultured for 3 days on solid YPD medium. Cells were scraped from the plates, washed with distilled water, resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 20 μg of leupeptin per ml, 20 μg of antipain per ml, 20 μg of pepstatin per ml, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and broken with a French press. Lysates were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 45 min. The supernatants were precleared by incubating for 1 h at 4°C with protein A-Sepharose. After centrifugation at 150 × g for 5 min, aliquots from each supernatant were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-C. albicans Bcy1p IgG bound to protein A-Sepharose beads. The resin was then pelleted and washed with 10 mM sodium phosphate containing 75 mM NaCl. The final pellet was resuspended in Laemmli buffer (17), boiled, and spun down at 10,000 rpm. The supernatant was saved for SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

GFP fluorescence microscopy.

For fluorescence microscopy, cells were used without fixation. Nuclei were stained by the addition of 1 μg of 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) per ml to the cell suspension. Cells were visualized with an Olympus BX50 fluorescence microscope. Images were taken with a CoolSNAP-Procf color digital camera kit with Image Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics).

Protein determination.

Protein concentration was determined with bovine serum albumin as the standard (4).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of C. albicans BCY1 has been submitted to GenBank under accession number AF317472.

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of C. albicans BCY1.

Based on the identity of two amino acid segments found in protein kinase A regulatory subunits from S. cerevisiae (40), Blastocladiella emersonii (22), and mouse (33), we designed a set of oligonucleotides for PCR amplification of a region of the C. albicans homologue with total genomic DNA. One of the amplicons, showing 59% identity with a region of the S. cerevisiae BCY1 gene (40), was used as a probe to screen a C. albicans genomic fosmid library. Southern analysis revealed that C. albicans BCY1 was present in a 7.4-kb EcoRV fragment from fosmid 4A12. This DNA fragment was subcloned in pUC19, and a restriction map was established (Fig. 1). A 2,679-bp region encoding C. albicans BCY1 was sequenced, revealing a 1,377-bp open reading frame encoding a putative 459-amino-acid protein. Ten and eight nucleotide differences were observed when comparing the open reading frame sequence with contigs 6-1620 and 6-2053, respectively, from the Candida genomic sequencing project (http://www-sequence.stanford.edu/group/candida).

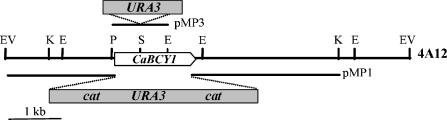

FIG. 1.

Restriction map of the C. albicans BCY1 locus. The thick line represents a 7.4-kb EcoRV C. albicans genomic fragment containing the BCY1 gene from fosmid 4A12. The white arrow indicates the position of the C. albicans BCY1 open reading frame. pMP1 and pMP3 refer to the constructions made to delete the C. albicans BCY1 alleles. Endonuclease restriction sites: E, EcoRI; EV, EcoRV; K, KpnI; P, PinAI; S, StyI.

At the protein level, the sequence was 100% identical to that of open reading frame SRA1 (another name for BCY1 in S. cerevisiae) on contig 6-2053 (only a partial 141-amino-acid SRA1 open reading frame could be obtained from the other contig). The C. albicans Bcy1p deduced sequence shows an overall identity of 62% with the S. cerevisiae homologue and shares a high similarity with other fungal regulatory subunits (Fig. 2). Our previous characterization of C. albicans Bcy1p expressed in Escherichia coli (43) confirmed the main features predicted from the analysis of the deduced amino acid sequence.

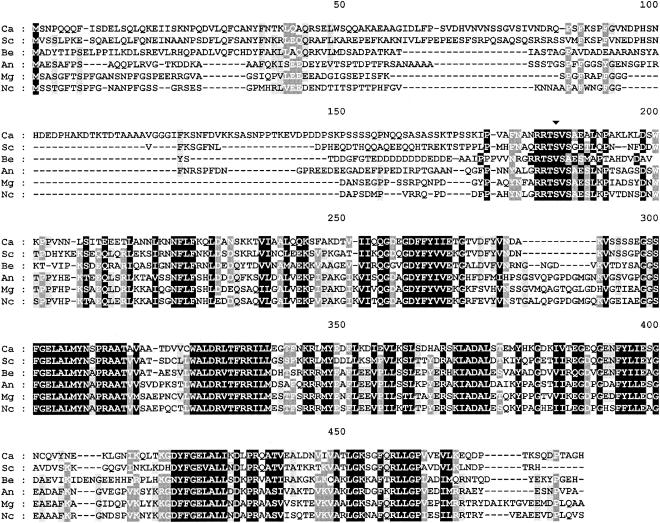

FIG. 2.

Sequence alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of C. albicans BCY1 with those of R subunits from several fungal species. Identities are in black boxes. Gaps introduced for alignment are indicated by dashes. The alignment was performed with Clustal W (38) and edited with GeneDoc (version 2.6.002). Potential phosphorylation sites are indicated by an arrowhead (▾). C.a., Candida albicans; S.c., Saccharomyces cerevisiae (accession number M15756); B.e., Blastocladiella emersonii (accession number M81713); A.n., Aspergillus nidulans (accession number AF043231); M.g., Magnaporthe grisea (accession number AF024633); N.c., Neurospora crassa (accession number L78009).

Chromosomal deletion of C. albicans BCY1.

Current knowledge on the C. albicans morphogenetic transition between yeast-like growth and filamentous growth points toward a crucial, positive role for protein kinase A in the process (10). To further explore the biochemical mechanisms leading to intracellular activation of the enzyme, we performed experiments aimed at obtaining a C. albicans BCY1 null mutant by gene disruption with the Ura-blasting procedure. To that end, C. albicans BCY1::cat-URA3-cat deletion construct pMP1 (Fig. 1) was generated and used to transform C. albicans strain CAI4 (ura3/ura3). Nine of the transformants obtained were tested by Southern analysis, and two of them showed loss of a BCY1 allele (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Results of transformation experiments performed to delete both alleles of BCY1 in C. albicans strain CAI4

| Expected genotype (plasmid)a | No. of transformants tested by Southern analysis | No. of transformants of the expected genotype |

|---|---|---|

| BCY1/Δbcy1::cat-URA3-cat (pMP1) | 9 | 2 |

| Δbcy1::cat-URA3-cat/Δbcy1::cat (pMP1) | 113 | 0 |

| bcy1::cat-URA3-cat/Δbcy1::cat (pMP3) | 20 | 0 |

| BCY1/Δbcy1::cat-URA3-cat Δtpk2::cat/Δtpk2::cat (pMP1) | 16 | 5 |

| Δbcy1::cat-URA3-cat/Δbcy1::cat Δtpk2::cat/Δtpk2::cat (pMP1) | 31 | 9 |

The transformations were performed with the indicated plasmid.

One of the BCY1 hemizygous mutants (BCY1/Δbcy1::catURA3-cat) was used to obtain ura3 revertants able to grow in the presence of 5-fluoroorotic acid. Twenty-three colonies were analyzed by Southern blotting to confirm the loss of the URA3 marker gene. One of the confirmed revertants (BCY1/Δbcy1::cat) was selected for deletion of the second BCY1 allele with pMP1. Several transformations were performed, and a total of 113 transformants were tested by Southern analysis to detect deletion of the remaining BCY1 allele. However, none of them was found to be a BCY1 homozygous null mutant (Table 2). In most transformants, integration of the cat-URA3-cat cassette took place at the locus of the previously deleted allele. To prevent this, a new construct was designed (pMP3; Fig. 1) in which sequence homology with the deleted locus was minimized, the URA3 gene being inserted within the BCY1 coding sequence itself. Still, none of the 20 transformants tested by Southern analysis had the second BCY1 allele disrupted (Table 2).

Failure to isolate homozygous null mutants suggested that deletion of both BCY1 alleles in cells harboring wild-type protein kinase A levels might not be possible. To verify this hypothesis, we transformed a TPK1/TPK1 tpk2/tpk2 bcy1/bcy1 mutant with a copy of TPK2 placed under the control of the PCK1 inducible promoter. When incubated in SD medium (no induction of the promoter), the transformants grew relatively well. However, when CSAA was used (induction of the promoter), they grew very poorly (Fig. 3). All these results are in agreement with those recently reported stating that BCY1 is an essential gene in C. albicans (9).

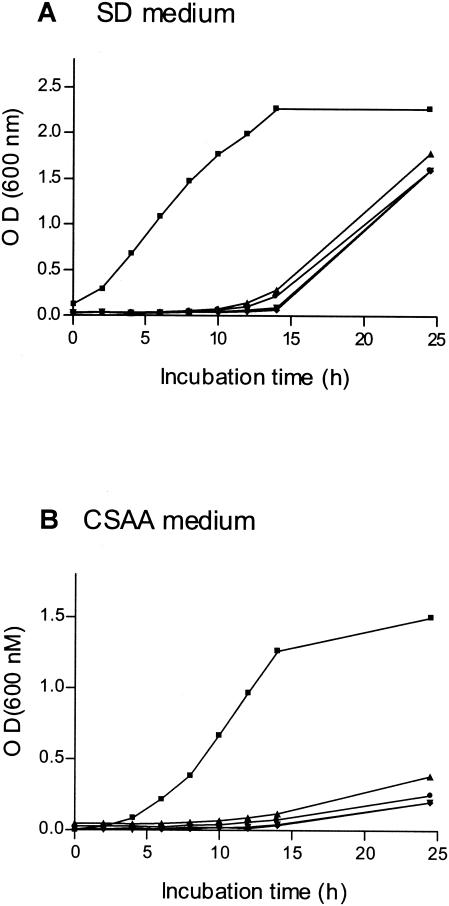

FIG. 3.

Effect of TPK2 overexpression on growth of the BCY1 null strain. A C. albicans TPK1/TPK1 tpk2/tpk2 bcy1/bcy1 mutant was transformed with plasmid pLS4. Four different transformants were tested (•, ⧫, ▴, ▾). The control strain was CAI4 transformed with plasmid pBI (▪). Strains were grown in noninducing medium SD (A) and in CSAA inducing medium (B) at 30°C with agitation (150 rpm). The optical density of the cultures was measured at 600 nm.

Therefore, a C. albicans strain lacking TPK2 (7) was used in another series of transformation experiments. In the first transformation, with pMP1, five of the 16 transformants tested by Southern analysis showed loss of a BCY1 allele (BCY/Δbcy1::cat-URA3-cat Δtpk2::cat/Δtpk2::cat). One of the transformants was selected and reverted back to uracil auxotrophy with 5-fluoroorotic acid. Upon transformation of the ura3 revertant (BCY1/Δbcy1::cat Δtpk2::cat/Δtpk2::cat) with pMP1, nine of the 31 transformants obtained were shown to be BCY1 null homozygotes (Δbcy1::cat-URA3-cat/Δbcy1::cat Δtpk2::cat/Δtpk2::cat) by Southern analysis (Table 2). One of them, selected by resistance to 5-fluoroorotic acid, was used for the experiments described below.

Biochemical characterization of the bcy1 tpk2 null mutant.

The absence of the regulatory subunit in the bcy1 tpk2 double mutant was assessed by Western blot analysis of crude protein extracts with a Bcy1p antiserum. As can be seen in Fig. 4, Bcy1p was expressed at comparable levels in the parental and H2D strains (lanes 1 and 2, respectively) but was absent in the bcy1 tpk2 double mutant (lane 3).

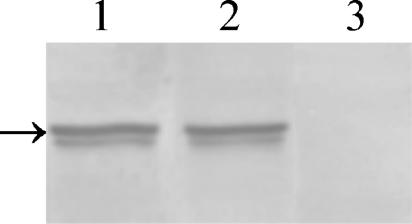

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis of crude extract from strains CAI4, H2D, and bcy1 tpk2. Equal amounts of protein were subjected to SDS-10% PAGE, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and reacted with anti-C. albicans Bcy1p antiserum as described in Materials and Methods. The arrow on the left indicates the migration position of Bcy1p.

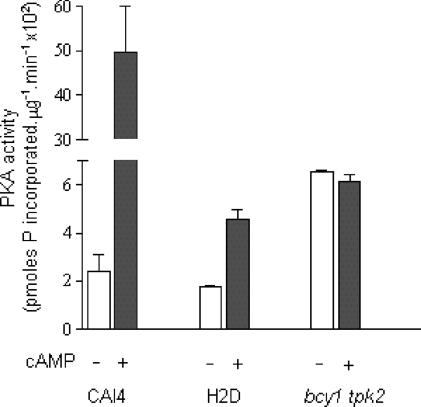

Lack of the regulatory subunit should result in cAMP-independent protein kinase A activity in the bcy1 tpk2 mutant. To assess this, protein kinase A activity and its cAMP dependence were evaluated in crude extracts from CAI4, H2D, and bcy1 tpk2 strains. As expected and also reported previously (7), protein kinase A activity was dependent on the addition of cAMP in the parental and H2D strains (Fig. 5). In contrast, the strain lacking Bcy1p displayed, as anticipated, a cAMP-independent protein kinase A activity (Fig. 5). Values also show that, in the presence of saturating amounts of cAMP, protein kinase A activity in the double mutant was similar to that of H2D (roughly 10% of the maximal activity of the wild-type strain). Taken as a whole, these results indicate that in the absence of the regulatory subunit, cells displayed a constitutive protein kinase A activity roughly similar to the maximal attainable activity in the tpk2 null strain.

FIG. 5.

Protein kinase A activity in crude extracts from CAI4, H2D and bcy1 tpk2 strains. Protein kinase A (PKA) activity was measured in aliquots of crude extracts from the three strains in the absence and in the presence of 10 μM cAMP as described in Materials and Methods. Values are means ± standard deviation from three independent experiments.

Phenotype of the bcy1 tpk2 null mutant.

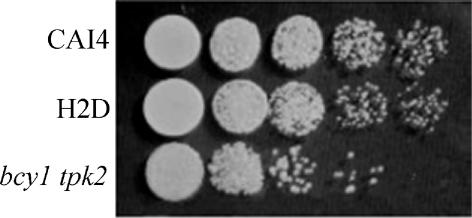

Cell morphology was not severely altered in the strain lacking BCY1 except for some heterogeneity in cell size. However, the bcy1 tpk2 mutant showed diminished growth in YPD liquid medium at 30°C compared to the wild-type and H2D strains. In addition, when using fresh cultures to inoculate solid YPD medium, the bcy1 tpk2 mutant strain gave at the most 30% of the colony number obtained with the wild-type and H2D strains (data not shown). Inoculation of solid YPD medium with serial dilutions of these cultures confirmed that cell viability was seriously affected in the bcy1 tpk2 mutant. However, the sizes of the colonies derived from the three strains were similar (Fig. 6), suggesting that the absence of BCY1 in the double mutant does not lead to any appreciable change in the rate of cell division. A distinctive feature of the bcy1 tpk2 mutant was the yellow color of the colonies grown in YPD plates, as opposed to the white color exhibited by the parental and H2D strains. A relationship between pigment biosynthesis and the cAMP signal transduction pathway has been described in several fungi (8, 16) and could explain the colonial phenotype of the double mutant.

FIG. 6.

Growth of strains CAI4, H2D, and bcy1 tpk2. Cells were grown in liquid YPD supplemented with uridine (50 μg/ml). The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of the cultures was adjusted to 0.1 with the same medium, and 5-μl aliquots from the cultures and from 10-fold serial dilutions were spotted onto YPD plates supplemented with uridine (50 μg/ml). Plates were incubated at 30°C for 2 days.

Previous results from our laboratory and from others (3, 6, 7, 37) clearly showed that protein kinase A activity plays a major role in the induction of C. albicans filamentous growth. We have previously shown (7) that in strain H2D, low levels of protein kinase A activity correlated with a reduced ability to germinate in liquid medium containing the inducer GlcNAc (50% germ tube formation compared to the parental strain). We also showed that the addition of protein kinase A activators to the induction medium significantly increased the number of cells forming germ tubes in the tpk2 null strain. These results, taken together with those arising from the overexpression of Tpk1p or Tpk2p (3, 37), led us to hypothesize that unregulated, constitutive protein kinase A activity in the C. albicans strain lacking BCY1 would allow cell filamentation even when incubated at 37°C in minimal medium without inducers. However, unexpectedly, we found that bcy1 tpk2 cells did not differentiate under these conditions but rather maintained a normal yeast-like shape, as do CAI4 and H2D (not shown).

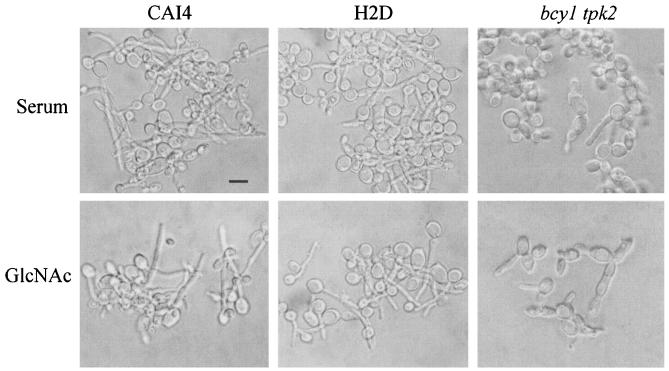

The germinative behavior of the bcy1 tpk2 mutant strain was then investigated by assessing hyphal formation in GlcNAc or serum inducing medium. As can be seen in Fig. 7, the strain lacking BCY1 failed to form germ tubes in liquid medium in the presence of GlcNAc. The culture was heterogeneous, being composed of a mixture of highly enlarged spherical cells and short chains of elongated, aberrantly shaped cells attached to one another. Filamentation was also greatly altered when hyphal growth was induced in liquid medium containing serum. Sparse, short pseudohyphae emerging from enlarged cells could be observed, together with heterogeneous round, nongerminated cells. Figure 7 also shows that strains CAI4 and H2D exhibited normal hyphal morphology in medium containing either GlcNAc or serum, as previously reported (7). Cells from the double mutant strain which had been incubated for 2 h in either induction medium were able to resume yeast-like growth when shifted to 28°C in YPD (not shown).

FIG. 7.

Germinative behavior of strains CAI4, H2D, and bcy1 tpk2. Stationary-phase yeast cells were induced to germinate for 2 h at 37°C in MnCl2/imidazole medium in the presence of 10% horse serum or 10 mM GlcNAc. Bar, 5 μm.

It could be argued that the presence of constitutive protein kinase A activity may have a toxic effect, interfering with cells' ability to differentiate. It is also possible that the absence of the regulatory subunit could promote a mislocalization of the enzyme, contributing to the observed phenotype. In S. cerevisiae, it has been demonstrated that the protein kinase A regulatory subunit localizes to the nucleus in a growth phase- and carbon source-dependent manner and that it directs localization of the associated catalytic subunit (14). If a similar Bcy1p-dependent targeting of the catalytic subunit to the nucleus occurs in C. albicans, an aberrant distribution of the enzyme might be expected in the bcy1 tpk2 double mutant strain, with severe consequences for the chain of events related to the cAMP/protein kinase A signaling pathway.

Expression and subcellular localization of a fused Tpk1-GFP protein.

To study the subcellular localization of Tpk1p, we fused the green fluorescent protein (GFP) to its C terminus. The modification was performed on one of the TPK1 alleles in strains CAI4, H2D, and bcy1 tpk2. It is worthwhile mentioning that the genomic modification performed left the fused genes under the control of the intact TPK1 promoter. The presence of the Tpk1-GFP fusion protein did cause any detectable alteration in the cells, the modified strains behaving like the corresponding parental strains with respect to growth and morphogenesis (not shown).

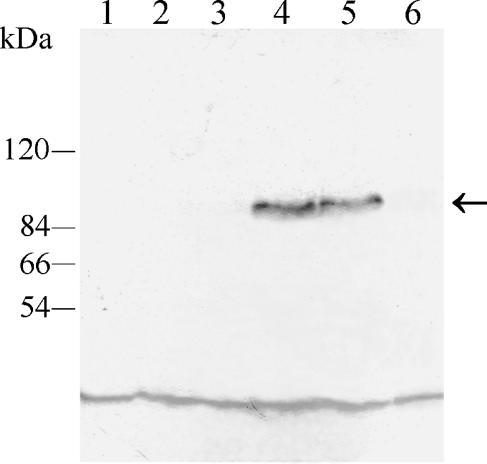

Interaction of the Tpk1-GFP fusion protein with Bcy1p inside the cell was demonstrated by immunoprecipitation of the tagged protein with anti-C. albicans Bcy1p antiserum. The immunoprecipitate was analyzed by Western blotting with a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody as described in Materials and Methods. As can be seen in Fig. 8, the antibody recognized a 96-kDa band, the expected molecular mass for the GFP-tagged Tpk1p, in extracts from strains ASM1 and ASM2 (lanes 4 and 5, respectively). No protein was detected in extracts from strains lacking the fusion protein (CAI4, H2D and bcy1 tpk2; Fig. 8, lanes 1, 2, and 3, respectively) or in extracts from strain ASM3 which lacks Bcy1p (Fig. 8, lane 6), indicating that nonspecific precipitation did not occur. Coimmunoprecipitation of Tpk1-GFP with Bcy1p in ASM1 and ASM2 strongly suggests interaction of the two proteins inside the cell. No free GFP was detected in immunoblots of soluble extracts from each of the Tpk1p-GFP-tagged strains, suggesting that no significant proteolysis of the fusion protein occurred (not shown).

FIG. 8.

Coimmunoprecipitation of Tpk1-GFP with Bcy1p. S-100 fractions from strains CAI4, H2D, bcy1 tpk2, ASM1, ASM2, and ASM3 containing the same amounts of protein were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-C. albicans Bcy1p antiserum as described in Materials and Methods. Immunoprecipitates were resolved in SDS-7.5% PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and developed with a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody. Lanes: 1, parental strain CAI4; 2, mutant H2D strain; 3, bcy1 tpk2 double mutant strain; 4, ASM1 strain; 5, ASM2 strain; 6, ASM3 strain. The positions of molecular mass markers are indicated on the left. The arrow indicates the position of the 96-kDa fused protein band. The low-molecular-mass band observed in all lanes corresponds to a nonspecific reaction of the antibody.

Localization of Tpk1p in yeast cells expressing the GFP-tagged protein was assessed by fluorescence microscopy of cells grown in YPD or SD-uridine liquid and solid media. Fluorescence was not detected in logarithmic-phase cells from any of the three strains bearing the TPK1-GFP construction but was strong in stationary-phase cells grown in liquid or solid medium (see below). This result seems to indicate that expression of Tpk1p is growth phase regulated in C. albicans, at least in glucose-containing medium. Since it has been reported that simultaneous deletion of TPK1 and TPK2 appears to be lethal (3), a low level of Tpk1p expression in the logarithmic phase, undetectable by fluorescence visualization, could explain the survival of the tpk2 null mutant strain.

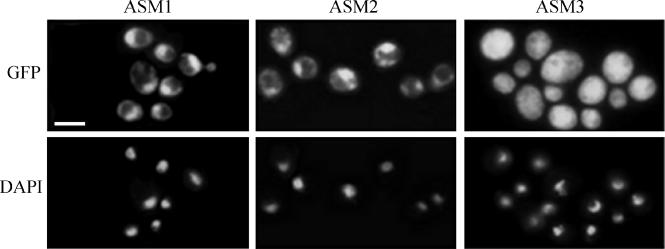

Subcellular localization of the Tpk1-GFP fusion protein in stationary-phase cells from solid SD-uridine medium can be seen in Fig. 9. In the CAI4 and tpk2 mutant cells, the Tpk1-GFP fusion protein localized mainly to the nucleus, whereas it was distributed throughout the cell in the bcy1 tpk2 double mutant (Fig. 9, upper panel). Although localization of Tpk2p has not been evaluated per se, the fact that a single gene codes for a protein kinase A regulatory subunit in C. albicans allows us to hypothesize that Bcy1p plays a decisive role in the subcellular localization of both protein kinase A isoforms.

FIG. 9.

Subcellular localization of Tpk1-GFP in wild-type and mutant strains. Localization of the fusion protein was visualized by fluorescence microscopy in strains ASM1, ASM2, and ASM3 (upper panels). Nuclei were visualized by DAPI staining (lower panels). Bar, 5 μm.

DISCUSSION

We have cloned and sequenced the C. albicans BCY1 gene encoding the protein kinase A regulatory subunit. Comparison of the Bcy1p deduced sequence with that of other fungi shows that it has the highest identity (62%) with the S. cerevisiae homologue and that it exhibits all the structural domains typical of type II regulatory subunits. The biochemical characterization of the expressed C. albicans Bcy1p reported previously confirmed all the predicted features of the protein (43).

To further investigate the role of protein kinase A in the yeast-to-hypha transition in C. albicans, we examined the effect of deleting the C. albicans BCY1 gene. Despite several attempts, it was not possible to simultaneously delete both BCY1 alleles in a wild-type genetic background. This could be accomplished only in a tpk2 null background, such a strain having much lower protein kinase A activity (7). As expected, protein kinase A activity in this bcy1 tpk2 double mutant was cAMP independent, indicating that the cells harbor a constitutively active enzyme.

A decrease in viability was observed in C. albicans yeast cells lacking Bcy1p. The existence of a direct relationship between high protein kinase A levels and diminished growth rate and stress response has been reported previously in S. cerevisiae (36, 38). In C. albicans, overexpression of Tpk1p caused a twofold reduction in growth rate which was attributed to the toxic effect of high protein kinase A activity provided by the free catalytic subunits (3). Therefore, it seems likely that in the absence of the regulatory subunit, the constitutive level of protein kinase A activity in the mutant (roughly 10% that of the wild type) is responsible for the observed phenotype. The role of protein kinase A in C. albicans yeast growth is not yet clear. It seems that at least one of the two protein kinase A genes must be expressed to sustain yeast cell viability (3). However, mutants with low levels of or even no cAMP (1, 29), expected to have low protein kinase A activity, are viable, although the growth rate of the latter is 2.5-fold lower than that of the wild type. Taken together, these results support the idea that although some protein kinase A activity is necessary to sustain growth, at certain levels it can become toxic to the cells (3).

Under the conditions examined, deletion of both BCY1 alleles in the tpk2 null mutant completely blocked the yeast-to-hypha transition. These results were unexpected because, according to our previous results (7), the absence of the regulatory subunit should lead to a constitutive level of protein kinase A activity sufficient to support morphogenesis in the mutant.

One possible explanation is that protein kinase A activity inside the cell is required only for certain steps of the process leading to cellular differentiation and that its presence at other times prevents the transition. In the absence of Bcy1p, no such regulation of protein kinase A activity by cAMP is possible.

We also examined the possibility that deletion of BCY1 could promote a mislocalization of the catalytic subunit, thus contributing to the germinative defect. We found that in strains having Bcy1p (CAI4 and H2D), the Tpk1-GFP fusion protein localizes predominantly to the nucleus. This was not the case in the bcy1 tpk2 double mutant, where it was observed to be dispersed throughout the cell. The conclusion that can be drawn from these findings is that in C. albicans, the presence of Bcy1p determines the nuclear localization of Tpk1p. This result is in agreement with recent reports on the subcellular localization of protein kinase A in S. cerevisiae; in rapidly growing yeast cells, Bcy1p was found to be predominantly nuclear, thus determining colocalization of Tpk1p, which was exported to the cytoplasm in response to an increase in cAMP concentration (14).

Although Bcy1p was not visualized directly in our experiments, we inferred that localization of Tpk1p in the nucleus of C. albicans is also a consequence of its association with nuclear Bcy1p. Preliminary experiments from our laboratory indicate that the fused Bcy1p-GFP also localizes to the nucleus, strengthening the idea that association of Tpk1p with Bcy1p drives its nuclear localization. The drastic change in subcellular distribution of the catalytic subunit in the absence of Bcy1p is expected to cause pleiotropic alterations in cellular metabolism. The lack of polarized growth could be one of the consequences of protein kinase A mislocalization.

The cAMP/protein kinase A signaling pathway controlling morphogenesis in C. albicans is comparable to that of S. cerevisiae with regard to function and hierarchical organization of the conserved components. Nuclear localization of C. albicans Bcy1p, inferred from this study, is another feature shared with S. cerevisiae. However, striking differences exist in the function of some of the homologues in the morphogenetic processes (10). For example, deletion of the unique BCY1 gene leads to a constitutive pseudohyphal growth phenotype in S. cerevisiae (27), while in C. albicans it appears to be lethal. Moreover, successful deletion of C. albicans BCY1 in a tpk2 null background leads to yeast-like growth (this study). The different roles played by protein kinase A, a key enzyme in the cAMP pathway, in the regulation of morphogenesis in the two organisms can explain this behavior.

In fact, in C. albicans, the two isoforms of the protein kinase A catalytic subunit (Tpk1p and Tpk2p) have a positive stimulatory function on hyphal formation (3, 7), whereas in S. cerevisiae the three isoforms have different roles in pseudohyphal growth, Tpk2p acting positively, while Tpk1p and Tpk3p act negatively (26, 28). Since Tpk2p does not translocate from the nucleus to the cytoplasm in response to the addition of external cAMP in S. cerevisiae (27), the absence of Bcy1p would not be expected to promote a mislocalization of Tpk2p. In contrast, in C. albicans the absence of Bcy1p prevents the cell from localizing Tpk1p to the nucleus.

Although pseudohypha formation in S. cerevisiae has been taken as a model for studying differentiation in other fungi, it is important to emphasize that true hyphal development is the result of a different cellular process (24, 41). Therefore, different morphological responses to modifications of conserved components of the same transduction pathway might be expected. Thus, a thorough study of the biochemical mechanisms controlled by components of the protein kinase A pathway in C. albicans is required to better understand what leads to hyphal growth, virulence, and pathogenicity in this fungus.

In eukaryotic cells, the existence of several signaling pathways in which protein kinase A is involved raises the question of how the different signals are specifically transduced. In higher eukaryotes, specificity is in part achieved by compartmentalization of protein kinase A through interactions with anchoring proteins that tether the kinase and its substrates close together in discrete subcellular locations inside the cell (11). No such proteins have been found yet in lower eukaryotes.

Nuclear localization of the regulatory subunit, previously demonstrated in S. cerevisiae (14) and now inferred in C. albicans, could be a mechanism used to localize the holoenzyme so that it can fulfill the metabolic needs of the cell. Sequence analysis of the C. albicans protein kinase A subunits (Tpk1p, Tpk2p, and Bcy1p) did not reveal any obvious signals for nuclear localization or nuclear export. Therefore, the existence of another protein(s) with the ability to drive the localization of protein kinase A in the cell seems likely. Since the final protein kinase A target in the pathway in C. albicans seems to be a transcription factor, Efg1p (2), the proximity of the kinase to its nuclear substrate could help the enzyme serve its regulatory role. It has also been reported that in S. cerevisiae, subcellular distribution of protein kinase A is metabolically regulated depending on the localization of Bcy1p, which in turn is regulated by Yak1-dependent phosphorylation of its N terminus (15).

In the same line, we have previously reported that the intramolecular phosphorylation of C. albicans Bcy1p in vitro leads to a decreased affinity for the catalytic subunit and that Bcy1p appears to be phosphorylated in vivo at a serine residue. A search in the Prosite database indicates that the regulatory subunit has other potential phosphorylation sites for several kinases (43). Taken together, these findings suggest that C. albicans Bcy1p could play a pivotal role in regulating the enzymatic activity and the availability of protein kinase A, in the nucleus or in the cytoplasm, depending on its own, growth phase-related physiological requirements.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cheryl A. Gale for providing plasmids for the construction of the green fluorescent fusion protein, Marcelo Rubinstein for providing the monoclonal anti-GFP antibody, Joachim F. Ernst for the kind gift of plasmids pLS4 and pBI, and Reid Gilmore for useful comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Medical Research Council of Canada and the Fonds Émile-Beaulieu to L.G., from the NIH (AI16567) to B.B.M., and from the Universidad de Buenos Aires, the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (ANPCyT), and the Fundación Antorchas to S.P. M.L.C., S.P., and S.S. are research members from CONICET. A.C. is an undergraduate student from the Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bahn, Y.-S., and P. Sundstrom. 2001. CAP1, an adenylate cyclase-associated protein gene, regulates bud-hypha transitions, filamentous growth, and cyclic AMP levels and is required for virulence of Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 183:3211-3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bockmühl, D. P., and J. F. Ernst. 2001. A potential phosphorylation site for an A-type kinase in the Efg1 regulator protein contributes to hyphal morphogenesis of Candida albicans. Genetics 157:1523-1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bockmühl, D. P., S. Krishnamurthy, M. Gerards, A. Sonneborn, and J. F Ernst. 2001. Distinct and redundant roles of the two protein kinase A isoforms Tpk1p and Tpk2p in morphogenesis and growth of Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 42:1243-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun, B. R., W. S. Head, M. X. Wang, and A. D. Johnson. 2000. Identification and characterization of TUP1-regulated genes in Candida albicans. Genetics 156:31-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castilla, R., S. Passeron, and M. L. Cantore. 1998. N-Acetyl-d-glucosamine induces germination in Candida albicans through a mechanism sensitive to inhibitors of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. Cell. Signalling 10:713-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cloutier, M., R. Castilla, N. Bolduc, A. Zelada, P. Martineau, M. Bouillon, B. B. Magee, S. Passeron, L. Giasson, and M. L. Cantore. 2003. The two isoforms of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit are involved in the control of dimorphism in the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 38:133-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dandekar, S., and V. V. Modi. 1980. Involvement of cyclic AMP in carotenogenesis and cell differentiation in Blakeslea trispora. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 628:398-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis, D. A., V. M. Bruno, L. Loza, S. G. Filler, and A. P. Mitchell. 2002. Candida albicans Mds3p, a conserved regulator of pH responses and virulence identified through insertional mutagenesis. Genetics 162:1573-1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ernst, J. 2000. Transcription factors in Candida albicans-environmental control of morphogenesis. Microbiology 146:1763-1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feliciello, A., M. E. Gottesman, and E. V. Avvedimento. 2001. The biological functions of A-kinase anchor proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 308:99-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fonzi, W. A., and M. Y. Irwin. 1993. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics 134:717-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerami-Nejad, M., J. Berman, and C. A. Gale. 2001. Cassettes for PCR-mediated construction of green, yellow, and cyan fluorescent protein fusions in Candida albicans. Yeast 18:859-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffioen, G., P. Anghileri, E. Imre, M. D. Baroni, and H. Ruis. 2000. Nutritional control of nucleocytoplasmic localization of cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic and regulatory subunits in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 275:1449-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffioen, G., P. Branduardi, A. Ballarini, P. Anghileri, J. Norbeck, M. D. Baroni, and H. Ruis. 2001. Nucleocytoplasmic distribution of budding yeast protein kinase A regulatory subunit Bcy1 requires Zds1 and is regulated by Yak1-dependent phosphorylation of its targeting domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:511-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hohl, N., P. Galland, and H. Senger. 1992. Altered pterin patterns in photobehavioral mutants of Phycomyces blakesleeanus. Photochem. Photobiol. 55:239-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leberer, E., D. Harcus, D. Dignar, L. Johnson, S. Ushinsky, D. Y. Thomas, and K. Schröppel. 2001. Ras links cellular morphogenesis to virulence by regulation of the MAP kinase and cAMP signaling pathways in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 42:673-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lengeler, K. B., R. C. Davidson, C. D'Souza, T. Harashima, W.-C. Shen, P. Wang, X. Pan, M. Waugh, and J. Heitman. 2000. Signal transduction cascades regulating fungal development and virulence. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:746-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lo, H.-J., J. R. Köhler, B. Didomenico, D. Loebenberg, A. Cacciapuoti, and G. R. Fink. 1997. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell 90:939-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mallet, L., G. Renault, and M. Jacquet. 2000. Functional cloning of the adenylate cyclase gene of Candida albicans in Saccharomyces cerevisiae within a genomic fragment containing five other genes, including homologues of CHS6 and SAP185. Yeast 16:959-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marques, M. V., and S. L. Gomes. 1992. Cloning and structural analysis of the gene for the regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase in Blastocladiella emersonii. J. Biol. Chem. 267:17201-17207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niimi, M. 1996. Dibutyryl cyclic AMP-enhanced germ tube formation in exponentially growing Candida albicans cells. Fungal Genet. Biol. 20:79-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oberholzer, U., A. Marcil, E. Leberer, D. Y. Thomas, and M. Whiteway. 2002. Myosin I is required for hyphal formation in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 1:213-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Odds, F. C. 1988. Candida and candidosis, 2nd ed. Bailliere Tindall, London, England.

- 26.Pan, X., and J. Heitman. 1999. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase regulates pseudohyphal differentiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:4874-4887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan, X., and J. Heitman. 2002. Protein kinase A operates a molecular switch that governs yeast pseudohyphal differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:3981-3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robertson, L. S., and G. R. Fink. 1998. The three yeast A kinases have specific signaling functions in pseudohyphal growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:13783-13787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocha, C. R. C., K. Schröppel, D. Harcus, A. Marcil, D. Dignard, B. N. Taylor, D. Y. Thomas, M. Whiteway, and E. Leberer. 2001. Signaling through adenylyl cyclase is essential for hyphal growth and virulence in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:3631-3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roskoski, R. 1983. Assay of protein kinase. Methods Enzymol. 99:3-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sabie, F. T., and G. M. Gadd. 1992. Effect of nucleosides and nucleotides and the relationship between cellular adenosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate cyclic AMP and germ tube formation in Candida albicans. Mycopathologia 119:147-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 33.Scott, J. D., M. B. Glaccum, M. J. Zoller, M. D. Uhler, D. M. Helfman, G. S. McKnight, and E. G. Krebs. 1987. The molecular cloning of a type II regulatory subunit of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase from rat skeletal muscle and mouse brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:5192-5196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shepherd, M. G., C. Y. Yin, S. P. Ram, and P. A. Sullivan. 1980. Germ tube induction in Candida albicans. Can. J. Microbiol. 26:21-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherman, F., G. R. Fink, and J. B. Hicks. 1983. Methods in yeast genetics, p. 61-62. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 36.Smith, A., M. P. Ward, and S. Garret. 1998. Yeast protein kinase A represses Mns2p/Mns4p-dependent gene expression to regulate growth, stress response and glycogen accumulation. EMBO J. 17:3556-3564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sonneborn, A., D. P. Bockmühl, M. Gerards, K. Kurpanek, D. Sanglard, and J. F. Ernst. 2000. Protein kinase A encoded by TPK2 regulates dimorphism of Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 35:386-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thevelein, J. M., L. Cauwenberg, S. Colombo, J. H. De Winde, M. Donation, F. Dumortier, L. Kraakman, K. Lemaire, P. Ma, D. Nauwelaers, F. Rolland, A. Teunissen, P. Van Dijck, M. Versele, S. Wera, and J. Winderickx. 2000. Nutrient induced signal transduction through the protein kinase A pathway and its role in the control of metabolism, stress resistance, and growth in yeast. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 26:819-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toda, T., S. Cameron, P. Sass, M. Zoller, J. D. Scott, B. McMullen, M. Hurwitz, E. G. Krebs, and M. Wigler. 1987. Cloning and characterization of BCY1, a locus encoding a regulatory subunit of the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:1371-1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wendland, J. 2001. Comparison of morphogenetic networks of filamentous fungi and yeast. Fungal Genet. Biol. 34:63-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson, B., D. Davis, and A. Mitchell. 1999. Rapid hypothesis testing with Candida albicans through gene disruption with short homology regions. J. Bacteriol. 181:1868-1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zelada, A., R. Castilla, S. Passeron, L. Giasson, and M. L. Cantore. 2002. Interactions between regulatory and catalytic subunits of the Candida albicans cAMP-dependent protein kinase are modulated by autophosphorylation of the regulatory subunit. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1542:73-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zelada, A., S. Passeron, S. Lopez Gomes, and M. L. Cantore. 1998. Isolation and characterization of cAMP-dependent protein kinase from Candida albicans. Purification of the regulatory and catalytic subunits Eur. J. Biochem. 252:245-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]