Abstract

Whole-genome analysis by 62-strain microarray showed variation in resistance and virulence genes on mobile genetic elements (MGEs) between 40 isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strain CC22-SCCmecIV but also showed (i) detection of two previously unrecognized MRSA transmission events and (ii) that 7/8 patients were infected with a variant of their own colonizing isolate.

TEXT

Hospitals are reservoirs of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates that commonly cause invasive infections. Control of MRSA incidence and spread requires precise approaches for detecting epidemiological relationships between bacteria.

Comparative genomics has revealed that the majority of human S. aureus isolates belong to 10 major lineages (6). Only five lineages that have acquired methicillin resistance are responsible for the majority of hospital-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA) infections (9). Lineages are defined by genes encoding surface-expressed proteins and their regulators, and these genes are highly stable (7). In contrast, 20% of the genome is constituted of mobile genetic elements (MGEs), including bacteriophages, plasmids, S. aureus pathogenicity islands (SaPIs), transposons, and staphylococcal chromosome cassettes (SCCs) (5). MGEs move between bacteria by horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and carry clinically relevant genes, including antibiotic resistance and virulence genes.

Current genotypic methods can successfully identify HA-MRSA clones (1–3). Studies using such methods have concluded that infections in MRSA-colonized individuals are caused by the patient's own colonizing strain (10, 12). However, these approaches do not distinguish variation within HA-MRSA clones or have sufficient power to identify close epidemiological relationships between isolates.

In this study, we used a newly developed 62-strain S. aureus microarray (SAM-62) to assess MGE gene distributions. We asked whether patients colonized with the major HA-MRSA strain in our hospital, CC22-SCCmecIV, who developed subsequent infection were infected by their own strain variant. As a control, we selected random MRSA isolates from multiple wards in our hospital during the same time period. Using this approach, we show that the patient's own colonizing flora is the major reservoir of infecting HA-MRSA, and we identified two previously unrecognized MRSA transmission events.

We analyzed 40 MRSA CC22 isolates from patients of St George's Healthcare NHS Trust, London, United Kingdom, including previously described paired colonization (at hospital admission), subsequent infecting isolates from 8 patients (4), and 24 invasive isolates taken at random from a range of wards and specimen types during the same 2-month period that the colonization isolates were collected. A sequenced CC22 MRSA isolate (5096) was also analyzed. Microarray experiments were performed using SAM-62 as previously described (8). The array design is available at BμG@Sbase (accession no. A-BUGS-38; http://bugs.sgul.ac.uk/A-BUGS-38) and ArrayExpress (accession no. A-BUGS-38). We performed hierarchical clustering analysis using a Euclidean distance metric based on 11,715 60-mer oligonucleotides representing MGE genes. Fully annotated microarray data have been deposited in BμG@Sbase (accession no. E-BUGS-128; http://bugs.sgul.ac.uk/E-BUGS-128) and also ArrayExpress (accession no. E-BUGS-128).

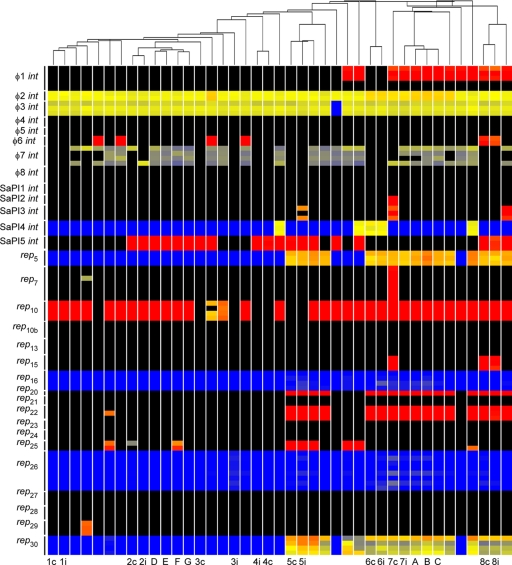

The core genome was highly conserved (data not shown); however, the MGE content of isolates varied considerably (Fig. 1). Some MGEs were highly frequent, such as φ2 (100%) and φ3 (98%) bacteriophages and rep10 (83%). The bacteriophage φ3 carries the immune evasion cluster (IEC) genes chp, scn, and sak that are prevalent in human-associated S. aureus (11, 13). rep10 plasmids were associated with ermC, encoding resistance to macrolide antibiotics. The Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) toxin, typically carried on the bacteriophage φ2, was absent in our isolates. The distribution of other MGEs was more varied, including φ1, φ6, SaPI2, SaPI3, SaPI4, SaPI5, rep5, rep7, rep15, rep20, rep22, rep29, and rep30 (Fig. 1). Many resistance genes had variable distributions, including aacA and aphD (24%), cadA (39%), cadDX (5%), dfrA (2%), ermC (80%), merAB (2%), mupA (7%), qacA (17%), smr (7%), and tetK (2%). Therefore, a diverse range of MGEs and virulence and resistance genes were present in MRSA strain CC22-SCCmecIV in our hospital at the same time.

Fig 1.

Clustering of HA-MRSA CC22-SCCmecIV isolates and distribution of bacteriophage int, SaPI int, and plasmid rep genes. Each vertical line represents an isolate. Carriage/invasive isolate pairs are denoted by a number and either c for carriage or i for invasive isolate. Isolates A, B, and C are HA-invasive isolates that have a close evolutionary relationship and form cluster 1 with isolate 7i. Isolates D, E, F, and G are HA-invasive isolates that have a close evolutionary relationship and form cluster 2. Note that isolates F and G originate from the same person. Isolates without labels are all HA-invasive isolates. Isolates have been clustered using data from 60-mer oligonucleotides that represent all genes on mobile genetic elements (MGEs). Horizontal lines represent different 60-mer-oligonucleotide probes specific to 8 bacteriophage int genes, 5 SaPI int genes, and 18 plasmid rep genes. The color in the main figure depicts whether the gene is present in the respective isolate (red or yellow, present; black or blue, absent).

Isolates were clustered by the presence and absence of MGE genes. A total of 7/8 pairs of colonization versus invasive isolates were closely related and carried the same MGEs (Fig. 1). Isolates 3c and 3i did not cluster together, but differed only by carriage of 3 SaPI genes, which could represent a single genetic event (data not shown). Isolates 7c and 7i did not cluster together and differed by carriage of SaPI2, SaPI3, rep7, and rep15, representing multiple genetic events (5); therefore, this patient was probably colonized and infected with different isolates. These data support previous findings that invasive infections in MRSA-colonized individuals are likely to be caused by the patient's own colonizing strain rather than by circulating hospital strains (10, 12). This analysis demonstrates that MGE profiling can accurately detect epidemiological relationships between MRSA isolates.

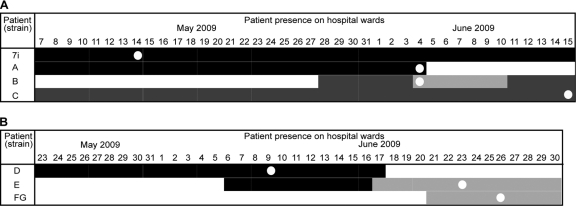

Clustering analysis revealed two groups of closely related MRSA isolates. Cluster 1 represents four invasive isolates (7i, A, B, and C) carrying the same MGEs, implying a close relationship between isolates (Fig. 1). We analyzed patient notes to search for evidence of interaction between patients (Fig. 2A). Patients 7 and A were present on the same ward, X, and their isolates were present in wound/peg site and wound site specimens on 14 May 2009 and on 4 June 2009, respectively. Interestingly, patient 7 did not develop an infection with his or her own nasal colonizing isolate. Patient B moved onto ward Y, a ward that shares medical teams with ward X, on 4 June 2009, and this patient had MRSA in a wrist site infection specimen on the same day. Patient B moved to ward Z on 11 June 2009 and, subsequently, patient C on ward Z acquired a MRSA infection (suprapubic catheter site swab sample taken on 15 June 2009). These data show that previously unrecognized MRSA transmission events can be identified using MGE profiling.

Fig 2.

Detection of two unrecognized transmission events. Each row represents a patient, and each shade of gray represents a different ward. The first time a patient was identified as MRSA positive is shown with a white spot. (A) Four patients on three different hospital wards are shown for each day by color (black, ward X; light gray, ward Y; dark gray, ward Z). Ward X and ward Y are sister wards of general medicine, located on the same floor, and they share the same medical teams. (B) Three patients on two different hospital wards are shown for each day by color (black, ward U; gray, ward W).

Cluster 2 represents four invasive isolates (D, E, F, and G) from three patients carrying the same MGEs (Fig. 1 and 2B). Patient D was present on ward U, and the isolate was taken from sputum on 9 June 2009. Interestingly, patient E was present on ward U from 6 June 2009 and moved onto ward W on 17 June 2009, and this patient had a wound site infection specimen on 23 June 2009. Isolates F and G were from the same patient on the same ward, W, 3 days later, indicating that the same MRSA strain may have transferred between two patients. Isolate F was from a graft site, and we had the opportunity to include a second isolate, isolate G, from a tissue swab. Interestingly, isolate F carried an additional plasmid (rep25) and resistance gene (smr) that were not found in isolate G, suggesting that MGE can transfer between isolates from the same patient.

In conclusion, we found that a highly diverse range of MGEs was present in a HA-MRSA CC22 clone in a hospital setting within a short time frame. In at least 7/8 cases, the colonizing strain of a patient at admission was highly similar to the strain causing subsequent infection. Our study demonstrates that unrecognized MRSA transmission events can be identified using MGE profiling.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Jason Hinds, Kate Gould, Denise Waldron, and Adam Witney from BμG@S (the Bacterial Microarray Group at St George's, University of London) for supply of the microarray and advice. We thank Juliane Krebes, Emma Budd, and Alastair Thornley for technical and logistical assistance.

This work was supported by the PILGRIM FP7 grant from the EU. We thank The Wellcome Trust for funding the multicollaborative microbial pathogen microarray facility under its Functional Genomics Resources Initiative.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 December 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Cockfield JD, Pathak S, Edgeworth JD, Lindsay JA. 2007. Rapid determination of hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineages. J. Med. Microbiol. 56:614–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Enright MC, Day NP, Davies CE, Peacock SJ, Spratt BG. 2000. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1008–1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harmsen D, et al. 2003. Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a university hospital setting by using novel software for spa repeat determination and database management. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5442–5448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Krebes J, Al-Ghusein H, Feasey N, Breathnach A, Lindsay JA. 2011. Are nasal carriers of Staphylococcus aureus more likely to become colonized or infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on admission to a hospital? J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:430–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lindsay JA, Holden MT. 2006. Understanding the rise of the superbug: investigation of the evolution and genomic variation of Staphylococcus aureus. Funct. Integr. Genomics 6:186–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lindsay JA, et al. 2006. Microarrays reveal that each of the ten dominant lineages of Staphylococcus aureus has a unique combination of surface-associated and regulatory genes. J. Bacteriol. 188:669–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCarthy AJ, Lindsay JA. 2010. Genetic variation in Staphylococcus aureus surface and immune evasion genes is lineage associated: implications for vaccine design and host-pathogen interactions. BMC Microbiol. 10:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McCarthy AJ, et al. 13 September 2011. The distribution of mobile genetic elements (MGEs) in MRSA CC398 is associated with both host and country. Genome Biol. Evol. [Epub ahead of print.] doi:10.1093/gbe/evr092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Robinson DA, Enright MC. 2003. Evolutionary models of the emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3926–3934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Safdar N, Bradley EA. 2008. The risk of infection after nasal colonization with Staphylococcus aureus. Am. J. Med. 121:310–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sung JM, Lloyd DH, Lindsay JA. 2008. Staphylococcus aureus host specificity: comparative genomics of human versus animal isolates by multi-strain microarray. Microbiology 154:1949–1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. von Eiff C, Becker K, Machka K, Stammer H, Peters G. 2001. Nasal carriage as a source of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. N. Engl. J. Med. 344:11–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Wamel WJ, Rooijakkers SH, Ruyken M, van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA. 2006. The innate immune modulators staphylococcal complement inhibitor and chemotaxis inhibitory protein of Staphylococcus aureus are located on beta-hemolysin-converting bacteriophages. J. Bacteriol. 188:1310–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]