Abstract

The impact of Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) on the outcome in Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia is controversial. We genotyped S. aureus isolates from patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) enrolled in two registrational multinational clinical trials for the genetic elements carrying pvl and 30 other virulence genes. A total of 287 isolates (173 methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA] and 114 methicillin-susceptible S. aureus [MSSA] isolates) from patients from 127 centers in 34 countries for whom clinical outcomes of cure or failure were available underwent genotyping. Of these, pvl was detected by PCR and its product confirmed in 23 isolates (8.0%) (MRSA, 18/173 isolates [10.4%]; MSSA, 5/114 isolates [4.4%]). The presence of pvl was not associated with a higher risk for clinical failure (4/23 [17.4%] versus 48/264 [18.2%]; P = 1.00) or mortality. These findings persisted after adjustment for multiple potential confounding variables. No significant associations between clinical outcome and (i) presence of any of the 30 other virulence genes tested, (ii) presence of specific bacterial clone, (iii) levels of alpha-hemolysin, or (iv) delta-hemolysin production were identified. This study suggests that neither pvl presence nor in vitro level of alpha-hemolysin production is the primary determinant of outcome among patients with HAP caused by S. aureus.

INTRODUCTION

The Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) is a bacteriophage-associated, bicomponent cytotoxin produced by some strains of Staphylococcus aureus. PVL induces host cell necrosis and apoptosis by producing pores in the cell membranes of neutrophils and other infected cells. The presence of PVL and the genetic elements coding for its production (two contiguous, cotranscribed genes, lukS and lukF, here referred to as pvl) has been strongly associated with a severe necrotizing pneumonia (13, 15). Although controversy persists, there is evidence that PVL is associated with severe disease in community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) due to S. aureus both in clinical reports (13, 15) and in some (10, 22), but not all (3, 20, 30, 49), in vivo model systems. However, the studies on the association between PVL and clinical outcomes in hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), a distinct clinical entity from CAP, are limited.

Hospital-acquired pneumonia is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality from nosocomial infections (9), and S. aureus is the leading cause of HAP in U.S. hospitals (12, 28, 34). In the current study, we tested the hypothesis that pvl presence in S. aureus isolates causing HAP was associated with a worse clinical outcome than the outcome of HAP caused by pvl-negative S. aureus counterparts. To test this hypothesis, we made use of a large international cohort of S. aureus isolates from patients with HAP. These isolates were collected in two identically designed phase III clinical trials for S. aureus HAP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and study settings.

The ATTAIN (Assessment of Telavancin for Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia) clinical trials were two identical phase III, randomized, double-blinded, parallel-group, multinational trials (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT00107952 and NCT00124020) studying the efficacy and safety of intravenous telavancin versus vancomycin for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) with a focus on patients with infections due to methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (35). Following randomization, patients were treated for 7 to 21 days with the study drug. From January 2005 to June 2007, a total of 1,503 patients were enrolled from 235 clinical centers in 38 countries. Patients were included in the current study if all of the following criteria were met: (i) inclusion in the modified all treated (MAT) population (n = 1,089), (ii) had monomicrobial infection with S. aureus at baseline, and (iii) had a clinical response of either “cure” or “failure” for the test-of-cure analysis. All patients or their legal guardian provided written informed consent. This study was approved by Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Clinical outcomes and definitions.

Clinical outcomes were established by site investigators. Outcomes were defined as either “cure” or “failure.” Cure was defined as (i) signs and symptoms of pneumonia improved to the point that no further antibiotics for pneumonia are required and (ii) baseline radiographic findings improved or did not progress. Failure was defined as (i) persistence or progression of signs and symptoms of pneumonia that still require antibiotic therapy within two calendar days of therapy with a potentially effective antistaphylococcal medication and/or (ii) death on or after day three attributable to primary infection. The MAT subgroup comprises all subjects who received at least one dose of study medication and who had a baseline respiratory pathogen identified from respiratory samples or blood cultures if no respiratory sample was positive.

PCR assays for genotyping.

S. aureus genomic DNA was extracted as described previously (5), using an ultraclean microbial DNA kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Inc., Carlsbad, CA) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. PCR assays were used to screen the S. aureus genome for 31 putative bacterial virulence determinants, including adhesin genes (fnbA, fnbB, clfA, clfB, cna, spa, sdrC, sdrD, sdrE, bbp, ebpS, and map-eap), toxin genes (pvl, eta, etb, tst, sea, seb, sec, sed, see, seg, seh, sei, and hlg), agr groups I to IV, staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec element (SCCmec) types I to IV, and other virulence genes (efb, icaA, chp, and the V8 protease gene). The primers and PCR conditions used to amplify the genes of interest were used as described previously (1, 5).

PVL Western blotting.

S. aureus isolates were cultured overnight from low-passage frozen stocks in CCY medium (3% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 2% Bacto-Casamino Acids, 2.3% sodium pyruvate, 0.63% Na2HPO4, and 0.041% KH2PO4, pH 6.7). Culture supernatants were prepared from bacteria at the early or late stationary phase of growth as described previously (17). LukF-PV and LukS-PV present in CCY culture supernatants were detected by Western blotting (immunoblotting) as described by Graves et al. (17), except polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes were used with the iBlot dry blotting system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California). The presence or absence of PVL subunits in S. aureus isolates was confirmed by two separate experiments. Quantitation of immunoblots from both experiments was performed using an Alpha Innotech gel documentation system (FluorChemFC2; Alpha Innotech Corp., San Leandro, CA) and AlphaView software version 3.0.3.

MLST.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed as described by Enright et al. (11). Sequences were analyzed in Seqman Pro (DNA STAR Inc., Madison, WI) and compared with those in the public database (www.mlst.net) to generate the sequence types (STs). STs were grouped into clonal complexes (CCs) by using eBURST analysis tools at http://eburst.mlst.net.

Alpha-hemolysin activity assay.

Alpha-hemolysin activity was measured by quantitative analysis of rabbit red blood cell (RBC) hemolysis as described earlier (19, 42) with the following slight modifications. Ten milliliters of tryptic soy broth (TSB) (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) in a 50-ml falcon tube was inoculated with a loopful of culture from a fresh plate of each strain and incubated at 37°C/220 rpm for overnight culture. An appropriate amount of overnight culture was inoculated into 10 ml of Mueller-Hinton broth 2 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in a 50-ml falcon tube to normalize the starting OD600 to 0.1 (∼107 CFU/ml) and incubated at 37°C/220 rpm for 20 h. After 20 h of incubation, the culture was spun down at 4°C/3,100 rpm for 10 min to remove the pellets. The supernatant was then filter sterilized, transferred to a sterile tube, and stored at −80°C until further use.

The ability of the culture supernatant to lyse rabbit erythrocytes (RBCs) was tested in a 96-well format. To do this, 100 μl of 1:5-diluted culture supernatant (in 1× phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) of each strain was loaded into the first well and then serially diluted up to 1:80 in duplicate. After the dilution of each sample, 100 μl of 1% rabbit RBCs (Innovative Research, Novi, MI) in 1× PBS was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Following incubation, plates were centrifuged for 5 min, 100 μl of the supernatant was removed gently to a new microtiter plate, and absorbance was read at 550 nm. Hemolytic units (HU) per milliliter of alpha-hemolysin were defined as the inverse of the dilution causing 50% of hemolysis. Sterile distilled water served as the 100% hemolysis control (positive control), and 1× PBS was a negative control. All experiments were performed in triplicate and the results averaged. Mean alpha-hemolysin levels were defined as high if they were >10 hemolytic units (HU)/ml and low if they were ≤10 HU/ml. To ensure that no bias was introduced with this stratification, we repeated the analyses using cut points of 5 HU/ml and 7 HU/ml. No differences in the overall findings were introduced by varying the biological cut point definitions.

Delta-hemolysin activity assay.

A delta-hemolysin activity assay was performed to exclude the possibility of agr dysfunction as a potential cause of clinical outcome. Delta-hemolysin activity on sheep blood agar plates was determined as previously described (36). Briefly, on each sheep blood agar plate, the beta-hemolysin-producing strain S. aureus RN4220 was streaked vertically and test strains were streaked horizontally. After overnight incubation at 37°C, the plates were observed for the enhanced zone of hemolysis created by the interaction of the beta-hemolysin of RN4420 and the delta-hemolysin of the test strain. S. aureus NRS149 (RN6607), also named 502A (standard agr group II prototype, obtained from the Network on Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus [NARSA]), and S. aureus NRS 155 (RN9120, agr-null derivative of RN6607) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Statistical methods.

The goal of this study was to investigate associations between clinical outcome of patients with S. aureus HAP and the presence of pvl in the infecting strain. To accomplish this goal, genetically defined patient subgroups (i.e., pvl-positive versus pvl-negative subjects) were assessed with the two-sample t test for continuously distributed variables, Fisher's exact test for binomial variables, and the Fisher-Freeman-Halton test for more general categorical variables (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population according to the pvl gene status of the infecting pathogen among patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia

| Parameter | Value by PVL statusa |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA |

MSSA |

|||||||

| Total (n = 173) | pvl negative (n = 155) | pvl positive (n = 18) | P value | Total (n = 114) | pvl negative (n = 109) | pvl positive (n = 5) | P value | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||||

| Mean age (SD) (yr)b | 66.3 (15.91) | 66.7 (15.40) | 63.1 (20.04) | 0.364 | 56.4 (19.79) | 56.4 (20.21) | 56.4 (6.43) | 0.996 |

| Male sexc | 93 (53.8) | 80 (51.65) | 13 (72.2) | 0.134 | 66 (57.9) | 63 (57.8) | 3 (60.0) | 1.000 |

| Region of enrollmentc | ||||||||

| Europe | 48 (27.7) | 45 (29.0) | 3 (16.7) | 0.005 | 50 (43.9) | 49 (45.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0.519 |

| North America | 46 (26.6) | 35 (22.6) | 11 (61.1) | 27 (23.7) | 25 (22.9) | 2 (40.0) | ||

| Otherd | 79 (45.7) | 75 (48.4) | 4 (22.2) | 37 (32.5) | 35 (32.1) | 2 (40.0) | ||

| Prior antimicrobial therapyc | 127 (73.4) | 116 (74.8) | 11 (61.1) | 0.259 | 46 (40.4) | 42 (38.5) | 4 (80.0) | 0.156 |

| MRSA risk factorsc | ||||||||

| Hospitalization within previous 6 months | 109 (63.0) | 100 (64.5) | 9 (50.0) | 0.302 | 41 (36.0) | 40 (36.7) | 1 (20.0) | 0.653 |

| Antibiotic treatment within prior 3 months | 118 (68.2) | 108 (69.7) | 10 (55.6) | 0.285 | 37 (32.5) | 36 (33.0) | 1 (20.0) | 1.000 |

| Chronic illness | 144 (83.2) | 130 (83.9) | 14 (77.8) | 0.509 | 67 (58.8) | 63 (57.8) | 4 (80.0) | 0.647 |

| Prior infection with MRSA | 19 (11.0) | 17 (11.0) | 2 (11.1) | 1.000 | 2 (1.8) | 2 (1.8) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Admission from a nursing home or long term care facility | 34 (19.7) | 30 (19.4) | 4 (22.2) | 0.757 | 10 (8.8) | 10 (9.2) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Surgical procedure during current hospital stay | 46 (26.6) | 42 (27.1) | 4 (22.2) | 0.784 | 45 (39.5) | 44 (40.4) | 1 (20.0) | 0.647 |

| Residing in an area known to have a high prevalence of community-acquired MRSA | 37 (21.4) | 30 (19.4) | 7 (38.9) | 0.070 | 14 (12.3) | 14 (12.8) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Smoking statusc | ||||||||

| Current smoker | 33 (19.3) | 29 (19.0) | 4 (22.2) | 0.412 | 33 (29.2) | 30 (27.8) | 3 (60.0) | 0.377 |

| Ex-smoker | 66 (38.6) | 57 (37.3) | 9 (50.0) | 19 (16.8) | 19 (17.6) | 0 | ||

| Nonsmoker | 72 (42.1) | 67 (43.8) | 5 (27.8) | 61 (54.0) | 59 (54.6) | 2 (40.0) | ||

| Data missing | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| On hemodialysisc | 6 (3.5) | 6 (3.9) | 0 | 1.000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Currently in acute renal failurec | 16 (9.2) | 15 (9.7) | 1 (5.6) | 1.000 | 6 (5.3) | 6 (5.5) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Patient operative statusc | ||||||||

| Nonoperative | 132 (76.3) | 118 (76.1) | 14 (77.8) | 0.372 | 70 (61.4) | 66 (60.6) | 4 (80.0) | 1.000 |

| Emergency postoperative | 27 (15.6) | 23 (14.8) | 4 (22.2) | 29 (25.4) | 28 (25.7) | 1 (20.0) | ||

| Elective postoperative | 14 (8.1) | 14 (9.0) | 0 | 15 (13.2) | 15 (13.8) | 0 | ||

| With history of severe organ system insufficiency/immunocompromisedc | 10 (5.8) | 9 (5.8) | 1 (5.6) | 1.000 | 4 (3.5) | 4 (3.7) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Diabetes and cardiac comorbidityc | 118 (68.2) | 104 (67.1) | 14 (77.8) | 0.432 | 58 (50.9) | 55 (50.5) | 3 (60.0) | 1.000 |

| Respiratory insufficiency/failurec | 105 (60.7) | 93 (60.0) | 12 (66.7) | 0.799 | 76 (66.7) | 72 (66.1) | 4 (80.0) | 0.663 |

| On a ventilator at the time of randomizationc | 76 (43.9) | 71 (45.8) | 5 (27.8) | 0.210 | 49 (43.0) | 49 (45.0) | 0 | 0.069 |

| Baseline bacteremia with S. aureusc | 13 (7.5) | 10 (6.5) | 3 (16.7) | 0.139 | 8 (7.0) | 8 (7.3) | 0 | 1.000 |

| In ICUe at baselinec | 85 (49.1) | 77 (49.7) | 8 (44.4) | 0.805 | 61 (53.5) | 60 (55.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0.182 |

| Mean body mass index (SD) (kg/m2)b | 25.9 (6.72) | 25.9 (6.92) | 25.6 (4.73) | 0.819 | 26.8 (6.26) | 26.9 (6.23) | 24.8 (7.29) | 0.467 |

| Mean total APACHE II score (SD)b | 15.5 (5.99) | 15.6 (5.95) | 14.5 (6.44) | 0.449 | 13.4 (5.85) | 13.4 (5.82) | 12.4 (7.09) | 0.697 |

Excluding the P value columns, values shown are numbers (percentages) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

Assessed by two-sample t test.

Assessed by Fisher's exact test (for 2-by-2 tables) or the Fisher-Freeman-Halton test (for tables larger than 2 by 2).

“Other” includes Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile, China, India, Israel, Lebanon, Malaysia, Peru, Philippines, South Africa, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand.

ICU, intensive care unit.

The association between clinical outcome and pvl status was assessed, adjusting for potential confounding variables (Table 2). Multiple analyses were conducted, and each stratified on a different covariate. Exact methods were used to test the null hypothesis that the odds ratio equaled unity in all strata (that is, that there was no association between clinical outcome and pvl status), stratifying on the third variable.

Table 2.

Outcome for patients with Staphylococcus aureus hospital-acquired pneumonia stratified by clinically relevant characteristics

| Parameter | Value by PVL status |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA |

MSSA |

|||||

| Cure rate (%) |

P valuea | Cure rate (%) |

P valuea | |||

| pvl negative (n = 155) | pvl positive (n = 18) | pvl negative (n = 109) | pvl positive (n = 5) | |||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age | 0.524 | 0.153 | ||||

| <65 yr | 50/54 (92.6) | 7/8 (87.5) | 55/63 (87.3) | 3/5 (60.0) | ||

| ≥65 yr | 73/101 (72.3) | 9/10 (90.0) | 38/46 (82.6) | 0/0 | ||

| Sex | 0.362 | 0.178 | ||||

| Male | 59/80 (73.8) | 12/13 (92.3) | 54/63 (85.7) | 1/3 (33.3) | ||

| Female | 64/75 (85.3) | 4/5 (80.0) | 39/46 (84.8) | 2/2 (100.0) | ||

| Region of enrollment | 0.349 | 0.215 | ||||

| Europe | 37/45 (82.2) | 3/3 (100.0) | 44/49 (89.8) | 0/1 (0.0) | ||

| North America | 26/35 (74.3) | 9/11 (81.8) | 20/25 (80.0) | 1/2 (50.0) | ||

| Otherb | 60/75 (80.0) | 4/4 (100.0) | 29/35 (82.9) | 2/2 (100.0) | ||

| Prior antimicrobial therapy | 0.531 | 0.167 | ||||

| Yes | 92/116 (79.3) | 10/11 (90.9) | 37/42 (88.1) | 2/4 (50.0) | ||

| No | 31/39 (79.5) | 6/7 (85.7) | 56/67 (83.6) | 1/1 (100) | ||

| MRSA risk factor | 0.531 | 0.145 | ||||

| Yes | 122/153 (79.7) | 16/18 (88.9) | 81/97 (83.5) | 2/4 (50.0) | ||

| No | 1/2 (50.0) | 0/0 | 12/12 (100) | 1/1 (100.0) | ||

| Hospitalization within previous 6 months | 0.532 | 0.193 | ||||

| Yes | 80/100 (80.0) | 8/9 (88.9) | 35/40 (87.5) | 1/1 (100.0) | ||

| No | 43/55 (78.2) | 8/9 (88.9) | 58/69 (84.1) | 2/4 (50.0) | ||

| Antibiotic treatment within prior 3 months | 0.531 | 0.175 | ||||

| Yes | 84/108 (77.8) | 9/10 (90.0) | 31/36 (86.1) | 0/1 (0.0) | ||

| No | 39/47 (83.0) | 7/8 (87.5) | 62/73 (84.9) | 3/4 (75.0) | ||

| Chronic illness | 0.531 | 0.197 | ||||

| Yes | 101/130 (77.7) | 13/14 (92.9) | 53/63 (84.1) | 2/4 (50.0) | ||

| No | 22/25 (88.0) | 3/4 (75.0) | 40/46 (87.0) | 1/1 (100.0) | ||

| Prior infection with MRSA | 0.533 | 0.165 | ||||

| Yes | 15/17 (88.2) | 1/2 (50.0) | 1/2 (50.0) | 0/0 | ||

| No | 108/138 (78.3) | 15/16 (93.8) | 92/107 (86.0) | 3/5 (60.0) | ||

| Admission from a nursing home or long term care facility | 0.533 | 0.206 | ||||

| Yes | 23/30 (76.7) | 3/4 (75.0) | 10/10 (100.0) | 0/0 | ||

| No | 100/125 (80.0) | 13/14 (92.9) | 83/99 (83.8) | 3/5 (60.0) | ||

| Surgical procedure during current hospital stay | 0.532 | 0.137 | ||||

| Yes | 33/42 (78.6) | 3/4 (75.0) | 35/44 (79.5) | 0/1 (0.0) | ||

| No | 90/113 (79.6) | 13/14 (92.9) | 58/65 (89.2) | 3/4 (75.0) | ||

| Residing in an area known to have a high prevalence of community-acquired MRSA | 0.356 | 0.143 | ||||

| Yes | 21/30 (70.0) | 5/7 (71.4) | 10/14 (71.4) | 0/0 | ||

| No | 102/125 (81.6) | 11/11 (100.0) | 83/95 (87.4) | 3/5 (60.0) | ||

| Smoking status | 0.530 | 0.182 | ||||

| Nonsmoker | 54/67 (80.6) | 5/5 (100.0) | 52/59 (88.1) | 2/2 (100.0) | ||

| Current or ex-smoker | 69/86 (80.2) | 11/13 (84.6) | 41/49 (83.7) | 1/3 (33.3) | ||

| On hemodialysis | 0.531 | 0.176 | ||||

| Yes | 5/6 (83.3) | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | ||

| No | 118/149 (79.2) | 16/18 (88.9) | 93/109 (85.3) | 3/5 (60.0) | ||

| Currently in acute renal failure | 0.532 | 0.193 | ||||

| Yes | 12/15 (80.0) | 1/1 (100.0) | 6/6 (100.0) | 0/0 | ||

| No | 111/140 (79.3) | 15/17 (88.2) | 87/103 (84.5) | 3/5 (60.0) | ||

| Patient was nonoperative | 0.532 | 0.150 | ||||

| Yes | 95/118 (80.5) | 13/14 (92.9) | 58/66 (87.9) | 3/4 (75.0) | ||

| No | 28/37 (75.7) | 3/4 (75.0) | 35/43 (81.4) | 0/1 (0.0) | ||

| History of severe organ system insufficiency/immunocompromised | 0.530 | 0.187 | ||||

| Yes | 5/9 (55.6) | 1/1 (100.0) | 4/4 (100.0) | 0/0 | ||

| No | 118/146 (80.8) | 15/17 (88.2) | 89/105 (84.8) | 3/5 (60.0) | ||

| Diabetes and cardiac comorbidity | 0.361 | 0.203 | ||||

| Yes | 76/104 (73.1) | 13/14 (92.9) | 43/55 (78.2) | 1/3 (33.3) | ||

| No | 47/51 (92.2) | 3/4 (75.0) | 50/54 (92.6) | 2/2 (100.0) | ||

| Respiratory insufficiency/failure | 0.532 | 0.196 | ||||

| Yes | 71/93 (76.3) | 10/12 (83.3) | 60/72 (83.3) | 2/4 (50.0) | ||

| No | 52/62 (83.9) | 6/6 (100.0) | 33/37 (89.2) | 1/1 (100.0) | ||

| On a ventilator at the time of randomization | 0.530 | 0.137 | ||||

| Yes | 54/71 (76.1) | 4/5 (80.0) | 40/49 (81.6) | 0/0 | ||

| No | 69/84 (82.1) | 12/13 (92.3) | 53/60 (88.3) | 3/5 (60.0) | ||

| Baseline bacteremia with S. aureus | 0.532 | 0.181 | ||||

| Yes | 7/10 (70.0) | 3/3 (100.0) | 7/8 (87.5) | 0/0 | ||

| No | 116/145 (80.0) | 13/15 (86.7) | 86/101 (85.1) | 3/5 (60.0) | ||

| In ICUc at baseline | 0.532 | 0.124 | ||||

| Yes | 59/77 (76.6) | 7/8 (87.5) | 48/60 (80.0) | 1/1 (100.0) | ||

| No | 64/78 (82.1) | 9/10 (90.0) | 45/49 (91.8) | 2/4 (50.0) | ||

| APACHE II score | 0.525 | 0.184 | ||||

| 0-13 points | 59/68 (86.8) | 8/8 (100.0) | 55/61 (90.2) | 2/3 (66.7) | ||

| 14-19 points | 41/51 (80.4) | 4/6 (66.7) | 26/30 (86.7) | 1/1 (100.0) | ||

| ≥20 points | 23/36 (63.9) | 4/4 (100.0) | 12/18 (66.7) | 0/1 (0.0) | ||

Two-sided P value from an exact test of the null hypothesis of no association between clinical outcome and pvl status, stratifying on the covariate.

“Other” includes Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile, China, India, Israel, Lebanon, Malaysia, Peru, Philippines, South Africa, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand.

ICU, intensive care unit.

The association between clinical outcome at test-of-cure and the presence/absence of each of a number of putative virulence genes (Table 3) was assessed using Fisher's exact test to test the null hypothesis of no association.

Table 3.

Association between putative virulence genes and clinical outcome among patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia due to methicillin-resistant or methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus

| Gene | MRSA (n = 173) |

MSSA (n = 114) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of patients with genotype | Cure rate (no./total [%]) with: |

P valuea | No. (%) of patients with genotype | Cure rate (no./total [%]) with: |

P valuea | |||

| Gene absent | Gene present | Gene absent | Gene present | |||||

| Adhesin genes | ||||||||

| fnbA | 173/173 (100.0) | 0/0 | 139/173 (80.3) | 114/114 (100.0) | 0/0 | 96/114 (84.2) | ||

| clfA | 142/173 (82.1) | 24/31 (77.4) | 115/142 (81.0) | 0.625 | 114/114 (100.0) | 0/0 | 96/114 (84.2) | |

| clfB | 125/173 (72.3) | 39/48 (81.3) | 100/125 (80.0) | 1.000 | 43/114 (37.7) | 62/71 (87.3) | 34/43 (79.1) | 0.292 |

| cna | 75/173 (43.4) | 79/98 (80.6) | 60/75 (80.0) | 1.000 | 52/114 (45.6) | 48/62 (77.4) | 48/52 (92.3) | 0.039 |

| spa | 173/173 (100.0) | 0/0 | 139/173 (80.3) | 114/114 (100.0) | 0/0 | 96/114 (84.2) | ||

| sdrC | 157/173 (90.8) | 15/16 (93.8) | 124/157 (79.0) | 0.202 | 49/114 (43.0) | 56/65 (86.2) | 40/49 (81.6) | 0.607 |

| sdrD | 154/173 (89.0) | 16/19 (84.2) | 123/154 (79.9) | 1.000 | 74/114 (64.9) | 35/40 (87.5) | 61/74 (82.4) | 0.595 |

| sdrE | 148/173 (85.5) | 19/25 (76.0) | 120/148 (81.1) | 0.588 | 68/114 (59.6) | 38/46 (82.6) | 58/68 (85.3) | 0.795 |

| bbp | 160/173 (92.5) | 9/13 (69.2) | 130/160 (81.3) | 0.288 | 107/114 (93.9) | 4/7 (57.1) | 92/107 (86.0) | 0.077 |

| ebpS | 173/173 (100.0) | 0/0 | 139/173 (80.3) | 114/114 (100.0) | 0/0 | 96/114 (84.2) | ||

| map-eap | 58/173 (33.5) | 92/115 (80.0) | 47/58 (81.0) | 1.000 | 14/114 (12.3) | 85/100 (85.0) | 11/14 (78.6) | 0.462 |

| fnbB | 120/173 (69.4) | 47/53 (88.7) | 92/120 (76.7) | 0.096 | 36/114 (31.6) | 66/78 (84.6) | 30/36 (83.3) | 1.000 |

| Toxin genes | ||||||||

| pvl | 18/173 (10.4) | 123/155 (79.4) | 16/18 (88.9) | 0.532 | 5/114 (4.4) | 93/109 (85.3) | 3/5 (60.0) | 0.176 |

| eta | 115/173 (66.5) | 51/58 (87.9) | 88/115 (76.5) | 0.104 | 63/114 (55.3) | 44/51 (86.3) | 52/63 (82.5) | 0.617 |

| etb | 11/173 (6.4) | 130/162 (80.2) | 9/11 (81.8) | 1.000 | 10/114 (8.8) | 89/104 (85.6) | 7/10 (70.0) | 0.193 |

| tst | 80/173 (46.2) | 74/93 (79.6) | 65/80 (81.3) | 0.849 | 47/114 (41.2) | 60/67 (89.6) | 36/47 (76.6) | 0.072 |

| sea | 104/173 (60.1) | 53/69 (76.8) | 86/104 (82.7) | 0.435 | 59/114 (51.8) | 45/55 (81.8) | 51/59 (86.4) | 0.610 |

| seb | 4/173 (2.3) | 135/169 (79.9) | 4/4 (100.0) | 1.000 | 7/114 (6.1) | 90/107 (84.1) | 6/7 (85.7) | 1.000 |

| sec | 36/173 (20.8) | 109/137 (79.6) | 30/36 (83.3) | 0.814 | 32/114 (28.1) | 67/82 (81.7) | 29/32 (90.6) | 0.391 |

| sed | 63/173 (36.4) | 88/110 (80.0) | 51/63 (81.0) | 1.000 | 24/114 (21.1) | 76/90 (84.4) | 20/24 (83.3) | 1.000 |

| see | 56/173 (32.4) | 92/117 (78.6) | 47/56 (83.9) | 0.540 | 19/114 (16.7) | 80/95 (84.2) | 16/19 (84.2) | 1.000 |

| seg | 109/173 (63.0) | 51/64 (79.7) | 88/109 (80.7) | 1.000 | 60/114 (52.6) | 45/54 (83.3) | 51/60 (85.0) | 1.000 |

| seh | 8/173 (4.6) | 131/165 (79.4) | 8/8 (100.0) | 0.358 | 16/114 (14.0) | 83/98 (84.7) | 13/16 (81.3) | 0.716 |

| sei | 160/173 (92.5) | 11/13 (84.6) | 128/160 (80.0) | 1.000 | 99/114 (86.8) | 11/15 (73.3) | 85/99 (85.9) | 0.252 |

| hlg | 172/173 (99.4) | 1/1 (100.0) | 138/172 (80.2) | 1.000 | 108/114 (94.7) | 5/6 (83.3) | 91/108 (84.3) | 1.000 |

| Others | ||||||||

| efb | 173/173 (100.0) | 0/0 | 139/173 (80.3) | 114/114 (100.0) | 0/0 | 96/114 (84.2) | ||

| icaA | 170/173 (98.3) | 3/3 (100.0) | 136/170 (80.0) | 1.000 | 113/114 (99.1) | 1/1 (100.0) | 95/113 (84.1) | 1.000 |

| chp | 128/173 (74.0) | 37/45 (82.2) | 102/128 (79.7) | 0.829 | 91/114 (79.8) | 19/23 (82.6) | 77/91 (84.6) | 0.758 |

| V8 | 160/173 (92.5) | 11/13 (84.6) | 128/160 (80.0) | 1.000 | 85/114 (74.6) | 26/29 (89.7) | 70/85 (82.4) | 0.556 |

| Agr group II vs. all others | 71/173 (41.0) | 85/102 (83.3) | 54/71 (76.1) | 0.249 | 34/114 (29.8) | 67/80 (83.8) | 29/34 (85.3) | 1.000 |

| SCC type II (4/non-4) | 29/173 (16.8) | 114/144 (79.2) | 25/29 (86.2) | 0.454 | 0/114 (0.0) | 96/114 (84.2) | 0/0 | |

Two-sided P value from Fisher's exact test of the null hypothesis of no association between clinical outcome and the presence/absence of the putative virulence genes. After adjustment for multiple comparisons to control the false discovery rate for the family of all the tests, there was no significant difference between clinical outcome and PVL status.

Due to small sample sizes, the association between clinical outcome at test-of-cure and the amount of alpha-lysin produced (>10 HU/ml versus ≤10 HU/ml) (Table 4) was tested, with the MRSA and MSSA strains pooled. Within PVL-positive and PVL-negative pathogens separately, an exact stratified Cochran-Mantel-Haenzel test was conducted via Monte Carlo simulation, stratifying on methicillin susceptibility (MRSA or MSSA). All reported P values are two-sided. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

Table 4.

Clinical outcome versus alpha-lysin production among patients with Staphylococcus aureus hospital-acquired pneumoniab

| S. aureus type and amt of alpha-lysina | PVL+ |

PVL− |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of isolates |

No. of isolates |

|||||

| Cure | Failure | Total | Cure | Failure | Total | |

| MRSA | ||||||

| High | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | 5 | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 1 |

| Low | 12 (92.3) | 1 (7.7) | 13 | 13 (76.5) | 4 (23.5) | 17 |

| Total | 16 (88.9) | 2 (11.1) | 18 | 14 (77.8) | 4 (22.2) | 18 |

| MSSA | ||||||

| High | 2 (100.0) | 0 | 2 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 2 |

| Low | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 3 |

| Total | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | 5 | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | 5 |

High, >10 HU/ml; low, ≤10 HU/ml.

The P value for MRSA and MSSA pooled was 1.00, as calculated by using an exact Monte Carlo Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, with stratification on methicillin susceptibility (MRSA or MSSA).

Results were obtained using SAS 9.2 (TS2M3) (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) run on a Windows-based server. When exact results could not be obtained from SAS procedures, they were obtained with either StatXact 9 PROCS run within the SAS environment or StatXact-8 run within Cytel Studio 8 (both from the Cytel Software Corporation, Cambridge, MA).

RESULTS

Study population and baseline characteristics.

Out of 1,503 patients enrolled in the ATTAIN studies, 287 patients from 127 centers in 34 countries met inclusion criteria for the current investigation. Bacterial isolates were available for all 287 patients. Of the 287 isolates, 173 (60.3%) were MRSA and 114 (39.7%) were MSSA. Baseline demographic characteristics of these patients are outlined in Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and outcome according to pvl presence.

Of the 287 isolates, 23 (8.0%) were positive for pvl (MRSA, 18/173 isolates [10.4%]; MSSA, 5/114 isolates [4.4%]). PVL protein was confirmed in all 23 isolates by Western blotting of culture supernatants (data not shown). No significant differences were identified in clinical characteristics of patients infected with pvl-positive and pvl-negative S. aureus with the exception of higher pvl prevalence in MRSA populations from North America (Table 1).

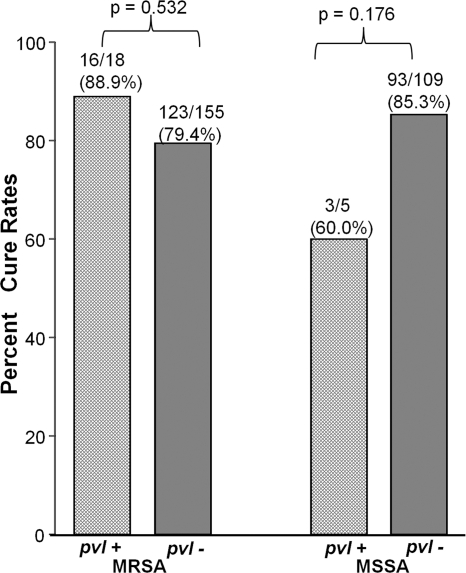

Next, we compared the outcomes of patients according to presence of pvl. No significant differences were identified in the clinical outcomes of patients with pvl-positive and pvl-negative S. aureus HAP, either overall (cure rates were 19/23 [82.6%] for pvl-positive cases versus 216/264 [81.8%] for pvl-negative cases; P = 1.00) or within methicillin susceptibility subgroups (for MRSA, 16/18 [88.9%] for pvl-positive cases versus 123/155 [79.4%] for pvl-negative cases [P = 0.532]; for MSSA, 3/5 [60.0%] for pvl-positive cases versus 93/109 [85.3%] for pvl-negative cases [P = 0.176]) (Fig. 1). There was also no significant difference in mortality rates among the pvl-positive and pvl-negative groups (data not shown). These findings persisted after adjustment for a number of potentially confounding clinical characteristics (Table 2). To look for possible correlation between the amounts of PVL production and clinical outcome, we next quantified the levels of LukS and LukF components of PVL in all 23 pvl-positive isolates. There was no difference in clinical outcome with the amount of PVL production (data not shown).

Fig 1.

Cure rates among patients due to methicillin-resistant (MRSA) or methicillin-sensitive (MSSA) Staphylococcus aureus hospital-acquired pneumonia according to presence or absence of pvl.

Clinical outcome of HAP according to presence of other virulence genes.

Next, we considered potential associations between other virulence genes and clinical outcome. The results of these comparisons are demonstrated in Table 3. After adjustment for multiple comparisons (data not shown) to control the false discovery rate for the family of all the tests, no significant associations between clinical outcome and presence or absence of any of the 30 other putative virulence genes were detected for patients with either MRSA or MSSA HAP (Table 3).

Alpha-hemolysin production and outcome of S. aureus HAP.

Because alpha-hemolysin has also been identified as a virulence factor in S. aureus pneumonia (2, 3) and might be acting in concert with PVL to augment pulmonary inflammation (4), we quantified alpha-hemolysin activity in the culture supernatant of all 23 pvl-constitutive isolates, as well as 23 randomly selected pvl-negative S. aureus isolates matched according to methicillin susceptibility. There was no evidence that clinical cure rates were related to high or low levels of alpha-hemolysin production in vitro (Table 4).

Effect of agr dysfunction in clinical outcome.

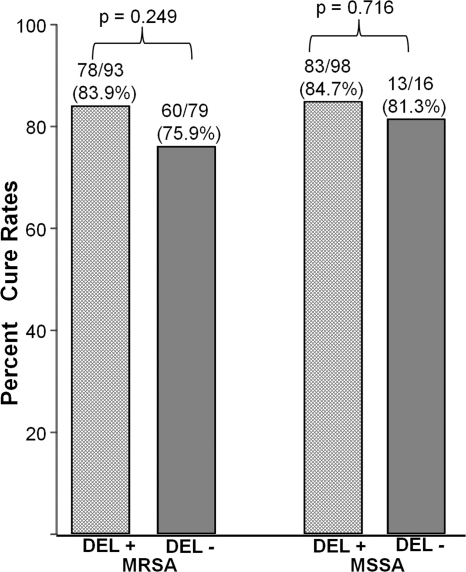

Because previous reports have suggested that dysfunction of the agr locus could result in attenuation in virulence (14, 39, 40, 46, 48), we evaluated agr function in all 286 S. aureus HAP isolates by using a delta-hemolysin activity/phenotyping assay. Of the 286 isolates, 191 (66.8%) exhibited a functional agr by the delta-hemolysin phenotyping assay (MRSA, 54.1% [93/172]; MSSA, 86.0% [98/114]). No significant association was identified between agr function and clinical outcome in either MRSA or MSSA HAP (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Cure rates among patients due to methicillin-resistant (MRSA) or methicillin-sensitive (MSSA) Staphylococcus aureus hospital-acquired pneumonia according to delta-lysin (DEL) production.

MLST and clinical outcome.

To consider the possibility that pvl presence could serve as a surrogate marker for a more virulent S. aureus clone, we used MLST to genotype all pvl-positive S. aureus isolates and a collection of randomly selected pvl-negative S. aureus isolates matched 1:1 (23 pvl-positive and 23 pvl-negative S. aureus isolates) (Table 5). Most pvl-positive S. aureus isolates belonged to CC8 (12/23 [52.2%]), whereas the most common CC among pvl-negative isolates was CC5 (11/23 [47.8%]). No clones were significantly associated with worse clinical outcome.

Table 5.

Clonal complex distribution among Staphylococcus aureus hospital-acquired pneumonia pvl-positive and pvl-negative isolates

| Clonal complex | No. of isolates |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Cure | Failure | |

| pvl positive | |||

| CC5 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| CC8 | 12 | 9 | 3 |

| CC15 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| CC30 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| CC59 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| CC88 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| CC121 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Singleton | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 23 | 19 | 4 |

| pvl negative | |||

| CC5 | 11 | 10 | 1 |

| CC8 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| CC15 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| CC22 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| CC30 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| CC97 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| CC121 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 23 | 16 | 7 |

DISCUSSION

The impact of pvl on the severity of S. aureus pneumonia is unknown. Using S. aureus isolates from a large collection of contemporary, geographically diverse, clinically well-characterized HAP patients, the current investigation found no evidence that pvl presence is associated with a more severe clinical course. This finding has several key implications.

The results of the present study demonstrate that the simple presence of pvl is not the primary outcome determinant in S. aureus HAP. Our finding is consistent with that of a recent study from Peyrani et al. (33). While an important hypothesis-generating observation, the Peyrani study was limited by its relatively small sample size, retrospective study design, limitation to MRSA-infected patients, geographically limited enrollment (4 U.S. centers), failure to confirm PVL production, and failure to consider the potential impact of other bacterial virulence characteristics. The current study overcomes all of these limitations to provide compelling evidence that factors other than the simple presence of PVL are the primary determinant of outcome in patients with HAP due to S. aureus. Our study findings persisted after adjusting for multiple patient and bacterial characteristics and are consistent with several other lines of evidence. First, the results of this study are consistent with three previous reports by our group that show a similar lack of association between pvl presence and higher likelihood of worse patient outcome in complicated skin and skin structure infections (1, 5, 44). In all of those studies, pvl presence was not associated with more severe infection, and in two of these studies (1, 5), pvl presence was actually associated with a significantly higher cure rate. Second, levels of PVL production do not appear to correlate with severity of infection (18). By enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), S. aureus strains from severe infections like necrotizing pneumonia were not the hyperproducers of PVL toxin compared to those associated with comparatively minor infections. Third, severe necrotizing pneumonia has been associated with pvl-negative community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) strains (43). Collectively, these findings support the notion that factors other than the simple presence of pvl are responsible for influencing severity in a variety of S. aureus infections (32), including HAP.

Alpha-hemolysin is an important virulence factor in pneumonia (2, 3). Because it may act in concert with PVL to induce pulmonary inflammation (4), we considered its additive impact on clinical severity of S. aureus HAP. No significant differences in cure rates were identified among the high alpha-lysin producers within pvl-positive or pvl-negative isolates. These findings suggest that our understanding of the pathogenesis of S. aureus pneumonia remains incomplete and that the determinants of infection severity are far more complex than the presence or absence of a few virulence characteristics.

Approximately one-third of the HAP isolates in the present study were delta-hemolysin deficient, suggesting that agr dysfunction did not reduce the capacity of S. aureus to cause invasive infection. The expression of virulence factors, including toxins and adhesins, in S. aureus is controlled by a global polycistronic regulatory locus, agr. This regulatory network encodes the quorum-sensing system that coordinates the expression of secreted and cell-associated virulence factors in a cell-density-dependent manner (29). Because delta-hemolysin is encoded by hld within the agr locus and is derived from the translation of RNAIII, the effector of agr regulon, its production is a marker of agr function (36). Loss of agr function has been linked to attenuated virulence (48) and has global effects on bacterial phenotypes (14, 40, 46) and increased mortality among S. aureus bacteremia patients (39). However, we found no evidence in the current investigation that agr dysfunction is associated with the outcome of HAP.

The prevalence of pvl in S. aureus varies widely among different infection types (7, 8, 21, 23–27, 33, 37, 38, 41, 45). Less than 10% of the S. aureus HAP isolates in this study contained pvl. This relatively low prevalence stands in sharp contrast to trends seen in soft tissue infections (1, 45) as well as in a pneumonia study in children (6).

Our study had several limitations. First, our study focused by design on patients with S. aureus HAP, while most prior reports that link PVL with pneumonia involved community-acquired S. aureus necrotizing pneumonia (15, 16). Thus, our findings would not apply to community-acquired S. aureus necrotizing pneumonia. This is an important distinction because of the prior health status of the infected individuals, i.e., those with community-acquired S. aureus necrotizing pneumonia were typically otherwise healthy, whereas patients with S. aureus HAP had risk factors for infection (and were thus highly susceptible to infection). Previously existing susceptibility of the HAP patients to infection could in part explain the finding that there was no significant association between clinical outcome and presence or absence of putative virulence genes (Table 3). Such molecules might simply be unnecessary to cause infection in these immunocompromised patients. Second, the proportion of isolates harboring and expressing PVL was low (<10%) and thus limited the statistical power of finding associations. Although we must remain cautious in the conclusions drawn from the present study, the fact that other investigators (33) have recently reported the same result strengthens its generalizability. Third, we evaluated alpha-hemolysin levels in vitro, and it remains unclear whether in vitro activity is a reflection of relative toxin production in vivo.

Study strengths include the fact that we have utilized one of the largest cohorts of patients with HAP, including large subgroups with S. aureus and MRSA. Therefore, although proportionally there were few pvl-positive isolates, this is likely to be one of the largest cohorts of patients with staphylococcal HAP to allow any comparison between pvl-positive and pvl-negative groups. Besides the larger size of the cohort, the other strengths of this investigation included its contemporary nature, multinational design, and detailed clinical and laboratory data. Finally, confirmation of pvl genotyping data by PVL Western blotting further strengthens the study findings.

In summary, this study provides evidence that PVL presence is not the primary determinant of outcome among patients with S. aureus HAP. This finding suggests that clinical outcome may be more significantly influenced by the presence of several bacterial virulence factors acting in concert than by the mere presence of pvl. Alternately, currently unrecognized or recently discovered virulence factors (e.g., phenol soluble modulins [31] or the novel bicomponent leukotoxin LukGH [47]) as well as the host genetic factors may also contribute to clinical outcome. The discovery of an exact virulence determinant needs further elucidation using appropriate in vivo models and using a collection of widely distributed well characterized strains. We anticipate future studies will combine clinical data with not only the presence/absence of any genotype but also technologies such as RNASeq to determine the relationships between pathogen transcriptome and clinical outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from Theravance, Inc., South San Francisco, CA. V. G. Fowler was supported in part by K24 AI093969 from the National Institutes of Health. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. S. Y. C. Tong is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Postdoctoral Training Fellowship (508829), an Australian-American Fulbright Scholarship, and a Royal Australasian College of Physicians Bayer Australia Medical Research Fellowship.

We thank NARSA for providing S. aureus NRS149 (RN6607) and S. aureus NRS 155 (RN9120) strains to be used as controls in this study.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 28 December 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Bae IG, et al. 2009. Presence of genes encoding the panton-valentine leukocidin exotoxin is not the primary determinant of outcome in patients with complicated skin and skin structure infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: results of a multinational trial. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3952–3957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bubeck Wardenburg J, Bae T, Otto M, Deleo FR, Schneewind O. 2007. Poring over pores: alpha-hemolysin and Panton-Valentine leukocidin in Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Nat. Med. 13:1405–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bubeck Wardenburg J, Palazzolo-Ballance AM, Otto M, Schneewind O, DeLeo FR. 2008. Panton-Valentine leukocidin is not a virulence determinant in murine models of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease. J. Infect. Dis. 198:1166–1170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bubeck Wardenburg J, Patel RJ, Schneewind O. 2007. Surface proteins and exotoxins are required for the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Infect. Immun. 75:1040–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Campbell SJ, et al. 2008. Genotypic characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from a multinational trial of complicated skin and skin structure infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:678–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carrillo-Marquez MA, et al. 2011. Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia in children in the era of community-acquired methicillin-resistance at Texas Children's Hospital. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 30:545–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen AE, et al. 2011. Randomized controlled trial of cephalexin versus clindamycin for uncomplicated pediatric skin infections. Pediatrics 127:e573–e580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Costello ME, Huygens F. 2011. Diversity of community acquired MRSA carrying the PVL gene in Queensland and New South Wales, Australia. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 30:1163–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dean N. 2010. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in community-acquired and health care-associated pneumonia: incidence, diagnosis, and treatment options. Hosp. Pract. (Minneap.) 38:7–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Diep BA, et al. 2010. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes mediate Staphylococcus aureus Panton-Valentine leukocidin-induced lung inflammation and injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:5587–5592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Enright MC, Day NP, Davies CE, Peacock SJ, Spratt BG. 2000. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1008–1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fagon JY, Maillet JM, Novara A. 1998. Hospital-acquired pneumonia: methicillin resistance and intensive care unit admission. Am. J. Med. 104:17S–23S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Francis JS, et al. 2005. Severe community-onset pneumonia in healthy adults caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying the Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:100–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fujimoto DF, Bayles KW. 1998. Opposing roles of the Staphylococcus aureus virulence regulators, Agr and Sar, in Triton X-100- and penicillin-induced autolysis. J. Bacteriol. 180:3724–3726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gillet Y, et al. 2002. Association between Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying gene for Panton-Valentine leukocidin and highly lethal necrotising pneumonia in young immunocompetent patients. Lancet 359:753–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gillet Y, et al. 2007. Factors predicting mortality in necrotizing community-acquired pneumonia caused by Staphylococcus aureus containing Panton-Valentine leukocidin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45:315–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Graves SF, et al. 2010. Relative contribution of Panton-Valentine leukocidin to PMN plasma membrane permeability and lysis caused by USA300 and USA400 culture supernatants. Microbes Infect. 12:446–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hamilton SM, et al. 2007. In vitro production of panton-valentine leukocidin among strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus causing diverse infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45:1550–1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kernodle DS, et al. 1995. Growth of Staphylococcus aureus with nafcillin in vitro induces alpha-toxin production and increases the lethal activity of sterile broth filtrates in a murine model. J. Infect. Dis. 172:410–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kobayashi SD, et al. 2011. Comparative analysis of USA300 virulence determinants in a rabbit model of skin and soft tissue infection. J. Infect. Dis. 204:937–941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuehnert MJ, et al. 2006. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization in the United States, 2001-2002. J. Infect. Dis. 193:172–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Labandeira-Rey M, et al. 2007. Staphylococcus aureus Panton-Valentine leukocidin causes necrotizing pneumonia. Science 315:1130–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee J, et al. 2011. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus obtained from the anterior nares of healthy Korean children attending daycare centers. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 15:e558–e563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li DZ, et al. 2011. Preliminary molecular epidemiology of the Staphylococcus aureus in lower respiratory tract infections: a multicenter study in China. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.). 124:687–692 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miller MB, et al. 2011. Prevalence and risk factor analysis for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization in children attending child care centers. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:1041–1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mithoe D, Rijnders MI, Roede BM, Stobberingh E, Moller AV. 18 June 2011. Prevalence of community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Panton-Valentine leucocidin-positive S. aureus in general practice patients with skin and soft tissue infections in the northern and southern regions of The Netherlands. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. [Epub ahead of print.] doi:10.1007/s10096-011-1316-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miyagi A, et al. 2010. Identification and characterization of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Okinawa, Japan. Rinsho Byori 58:869–877 (In Japanese.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Niederman MS. 2009. Treatment options for nosocomial pneumonia due to MRSA. J. Infect. 59(Suppl. 1):S25–S31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Novick RP, Geisinger E. 2008. Quorum sensing in staphylococci. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42:541–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Olsen RJ, et al. 2010. Lack of a major role of Staphylococcus aureus Panton-Valentine leukocidin in lower respiratory tract infection in nonhuman primates. Am. J. Pathol. 176:1346–1354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Otto M. 2010. Basis of virulence in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64:143–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Otto M. 2011. A MRSA-terious enemy among us: end of the PVL controversy? Nat. Med. 17:169–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Peyrani P, et al. 2011. Severity of disease and clinical outcomes in patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains not influenced by the presence of the Panton-Valentine leukocidin gene. Clin. Infect. Dis. 53:766–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Richards MJ, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP. 2000. Nosocomial infections in combined medical-surgical intensive care units in the United States. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 21:510–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rubinstein E, et al. 2011. Telavancin versus vancomycin for hospital-acquired pneumonia due to gram-positive pathogens. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52:31–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sakoulas G, et al. 2002. Accessory gene regulator (agr) locus in geographically diverse Staphylococcus aureus isolates with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1492–1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schaumburg F, et al. 2011. Population structure of Staphylococcus aureus from remote African Babongo Pygmies. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 5:e1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schaumburg F, et al. 2011. Virulence factors and genotypes of Staphylococcus aureus from infection and carriage in Gabon. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schweizer ML, et al. 2011. Increased mortality with accessory gene regulator (agr) dysfunction in Staphylococcus aureus among bacteremic patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:1082–1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shopsin B, et al. 2008. Prevalence of agr dysfunction among colonizing Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Infect. Dis. 198:1171–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Simões RR, et al. 2011. High prevalence of EMRSA-15 in Portuguese public buses: a worrisome finding. PLoS One 6:e17630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stevens DL, et al. 2007. Impact of antibiotics on expression of virulence-associated exotoxin genes in methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 195:202–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tomita Y, et al. 2008. Two cases of severe necrotizing pneumonia caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi 46:395–403 (In Japanese.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tong A, et al. 2010. Presence of pvl is associated with specific clinical characteristics in patients with complicated skin and skin structure infections (cSSSI) due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) & methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA): results from 2 multinational clinical trials. Abstr. 50th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., Boston, MA, 12 to 15 September 2010 http://www.icaac.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tong SY, et al. 2010. Clinical correlates of Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), PVL isoforms, and clonal complex in the Staphylococcus aureus population of Northern Australia. J. Infect. Dis. 202:760–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Traber K, Novick R. 2006. A slipped-mispairing mutation in AgrA of laboratory strains and clinical isolates results in delayed activation of agr and failure to translate delta- and alpha-haemolysins. Mol. Microbiol. 59:1519–1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ventura CL, et al. 2010. Identification of a novel Staphylococcus aureus two-component leukotoxin using cell surface proteomics. PLoS One 5:e11634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Villaruz AE, et al. 2009. A point mutation in the agr locus rather than expression of the Panton-Valentine leukocidin caused previously reported phenotypes in Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia and gene regulation. J. Infect. Dis. 200:724–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Voyich JM, et al. 2006. Is Panton-Valentine leukocidin the major virulence determinant in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease? J. Infect. Dis. 194:1761–1770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]