Abstract

Currently, there are no animal models of the most common human prion disorder, sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), in which prions are formed spontaneously from wild-type (WT) prion protein (PrP). Interestingly, bank voles (BV) exhibit an unprecedented promiscuity for diverse prion isolates, arguing that bank vole PrP (BVPrP) may be inherently prone to adopting misfolded conformations. Therefore, we constructed transgenic (Tg) mice expressing WT BVPrP. Tg(BVPrP) mice developed spontaneous CNS dysfunction between 108 and 340 d of age and recapitulated the hallmarks of prion disease, including spongiform degeneration, pronounced astrogliosis, and deposition of alternatively folded PrP in the brain. Brain homogenates of ill Tg(BVPrP) mice transmitted disease to Tg(BVPrP) mice in ∼35 d, to Tg mice overexpressing mouse PrP in under 100 d, and to WT mice in ∼185 d. Our studies demonstrate experimentally that WT PrP can spontaneously form infectious prions in vivo. Thus, Tg(BVPrP) mice may be useful for studying the spontaneous formation of prions, and thus may provide insight into the etiology of sporadic CJD.

Keywords: neurodegeneration, bioluminescence imaging, abbreviated incubation times

Prions are infectious proteins composed solely of alternatively folded, self-propagating protein conformers (1). One mammalian prion that causes transmissible neurodegenerative diseases in humans and animals is composed of PrPSc, the disease-causing isoform of the prion protein (PrP) (2). The accumulation of PrPSc in the brain causes profound neuropathologic changes, including spongiform degeneration, prominent astrocytic gliosis, and deposition of misfolded PrP. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is the most common prion disease in humans, with ∼85% of cases having a sporadic origin. The major pathogenic event in sporadic (s) CJD is the conformational conversion of wild-type (WT) cellular PrP into PrPSc. Although the molecular basis remains enigmatic, several hypotheses have been offered to explain the spontaneous production of WT prions in sCJD including: (i) a somatic mutation in the PrP gene in a small number of cells that generates a mutant PrP molecule capable of templating the formation of PrPSc from WT PrP on neighboring cells, (ii) discordant mRNA sequences that do not correspond exactly to the DNA sequences (3), and (iii) a stochastic misfolding process that generates PrPSc molecules from WT PrP randomly.

Although infectious prions have been formed spontaneously from WT PrP in vitro (4–8), there are currently no animal models of sCJD in which expression of WT PrP in the brain leads to spontaneous neurodegeneration. Some lines of transgenic (Tg) or knock-in mice expressing human or mouse PrP containing mutations linked to familial human prion disease develop a spontaneous neurodegenerative illness (9–14). However, other Tg lines expressing mutant PrP have failed to develop spontaneous disease (15). Furthermore, it has proven difficult to demonstrate the reproducible generation of prion infectivity in the brains of the aforementioned Tg mice expressing mutant PrP, in particular the ability to infect mice expressing WT mouse (Mo) PrP.

Interspecies transmission of sCJD prions to WT mice is an inefficient process characterized by long incubation periods and low transmission rates (16), a phenomenon referred to as the species barrier. In contrast, sCJD prions, as well as prions originating from several other species, are transmissible to bank voles (BV) (Myodes glareolus) and related species with relatively short incubation periods and high rates of transmission (17–19). The exceptional promiscuity of bank voles for prions from diverse species suggests that WT BVPrP may be particularly prone to adopting infectious conformations.

Prompted by this notion, we constructed Tg mice expressing WT BVPrP. Tg(BVPrP) mice developed a spontaneous neurologic disease that recapitulated all of the neuropathologic hallmarks of prion disease. Furthermore, this disease could be transmitted to young Tg(BVPrP) mice, to Tg mice overexpressing MoPrP, and to WT mice. These results argue that Tg(BVPrP) mice generate prions in their brains and therefore may be a useful model for dissecting the mechanisms that govern spontaneous prion formation.

Results

BVPrP and MoPrP differ at only eight positions in the mature forms of the protein (Fig. S1). Because BVPrP is polymorphic at codon 109, expressing either methionine or isoleucine (20), we generated Tg lines expressing either of the two WT BVPrP variants under the control of the hamster PrP promoter; these lines were denoted Tg(BVPrP,M109) and Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice. We established two lines of Tg(BVPrP,M109) mice and five lines of Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice; these Tg mice express BVPrP in the brain at levels ranging from 2.7-fold to 8.8-fold compared with levels of MoPrP expressed in WT Friend leukemia virus B (FVB) mouse brain (Table 1).

Table 1.

Spontaneous neurologic illness in Tg(BVPrP) mice

| Line | Codon 109 | PrP expression level, -fold | Mean incubation period ± SEM, d | Signs of neurol. dysfunction, n/n0 |

| Tg3118+/− | Methionine | 2.7 | >500 | 0/7 |

| Tg22019+/− | Methionine | 4.9 | >500 | 0/8 |

| Tg3574+/− | Isoleucine | 3.6 | 340 ± 26 | 14/14 |

| Tg3581+/− | Isoleucine | 5.3 | 218 ± 9 | 19/19 |

| Tg3574+/+ | Isoleucine | 5.7 | 173 ± 11 | 9/9 |

| Tg3615+/− | Isoleucine | 7.8 | 130 ± 7 | 23/23 |

| Tg3581+/+ | Isoleucine | 8.8 | 108 ± 7 | 7/7 |

PrP expression levels were determined relative to expression of WT MoPrP in FVB mouse brain. n, number of positive mice; n0, number of examined mice.

We observed that expression of the I109 polymorphism in five different lines of Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice resulted in signs of spontaneous neurologic dysfunction consistent with prion disease, including ataxia, circling, dysmetria, kyphosis, and proprioceptive deficits (Fig. 1A and Table 1). The onset of spontaneous disease was inversely dependent on the level of PrP expression in the brain, with earlier onset occurring in mice expressing the highest levels of BVPrP(I109) (Table 1). In contrast, two lines of Tg(BVPrP,M109) mice remained healthy for longer than 500 d, despite having BVPrP expression levels similar to those of Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice that developed spontaneous disease (Table 1). Neuropathologic analysis of the brains from Tg(BVPrP,I109) lines with spontaneous neurologic illness revealed prominent spongiform degeneration and intense astrocytic gliosis in the hippocampus as well as punctate PrP deposition in the corpus callosum in all mice examined (19/19) (Fig. 1 B–D and Fig. S2); activated microglia were also present in the cerebral cortex (Fig. 1E). Spongiform degeneration, astrocytic gliosis, and punctate PrP deposition were also observed in the thalamus and cerebellum (Fig. S2); plaque-like PrP deposits were found in some spontaneously ill mice (Fig. 1 F and G), including those that resembled the florid plaques present in patients with variant CJD (21). Increased amounts of PrP following phosphotungstic acid (PTA) precipitation were found in the brains of ill Tg(BVPrP,I109)3574+/− mice, hereafter denoted Tg3574+/− mice, compared with young Tg3574+/− mice, which only exhibited background levels of PTA-precipitable PrP (Fig. 1H). Protease-resistant PrP was observed following digestion of brain homogenates from spontaneously ill Tg3574+/− mice with 3 μg/mL of proteinase K (PK); however, no protease-resistant PrP was observed after limited digestion with 50 μg/mL of PK (Fig. 1H). In contrast, inoculation of Tg3574+/− mice with meadow vole (MV)-adapted Rocky Mountain Laboratory (RML) prions (22) resulted in the production of stereotypical PK-resistant PrP (Fig. 1H). Real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC) experiments (23) demonstrated that brain homogenates from three lines of spontaneously ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice were significantly better at seeding the polymerization of recombinant MoPrP to an amyloid fibrillar form than brain homogenates from either young Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice or WT mice (Fig. 1I). The seeding activity of brain homogenates from spontaneously ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice in the RT-QuIC assay was variable: for the majority of samples, only a proportion of the replicate reactions generated a positive result (Table S1), potentially indicating a low titer or stochastic formation of the amyloid-inducing species (23). Together, these results argue that Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice develop a spontaneous neurologic illness that was characterized by conformationally altered and comparatively protease-sensitive PrP in the brain as well as by neuropathologic changes typical of prion disease.

Fig. 1.

Spontaneous neurologic illness in Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice. (A) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for various lines of Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice. (B–G) Neuropathologic features of spontaneous neurologic disease in Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice. Spongiform degeneration (B), astrocytic gliosis (GFAP labeling, C), and punctate PrP deposition (PrP labeling, yellow arrows in corpus callosum; D) were present in the hippocampus, and activated microglia (Iba1 labeling, E) were observed in the cerebral cortex of a spontaneously ill Tg3581+/− mouse. Plaque-like PrP deposits were present in the parietal cortex of spontaneously ill Tg3581+/− (F) and Tg3615+/− (G) mice. (Scale bar in B–E, 100 μm; in F and G, 50 μm.) cc, corpus callosum; CA1, CA1 layer of pyramidal neurons. (H) Immunoblots for PrP. The brains of spontaneously ill Tg3574+/− mice contained increased levels of PTA-precipitable PrP compared with young asymptomatic mice, but no protease-resistant PrP was seen after digestion with 50 μg/mL of PK (“high”), as was observed in mice inoculated with meadow vole-passaged RML prions (RML→MV). Using milder digestion conditions (“low,” 3 μg/mL of PK), misfolded PrP could be detected in the brains of spontaneously ill Tg3574+/− mice. (I) RT-QuIC analysis of brain homogenates from young or spontaneously ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice. Significantly greater seeding activity was observed in the brains of ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice compared with asymptomatic young Tg3574+/− mice and wild-type FVB mice. Each data point represents the mean fluorescence value obtained from six replicates of an individual brain sample. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

Previously, it was shown that spontaneous disease in mice expressing a mutant PrP linked to the familial prion disorder Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease could be accelerated by inoculation of brain homogenate from spontaneously ill mice into young animals (10, 24–26). To determine whether a similar acceleration could be observed in Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice, we inoculated ∼2-mo-old Tg3581+/− and Tg3574+/− mice with brain homogenate from spontaneously ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice. All inoculated Tg3581+/− and Tg3574+/− mice developed signs of neurologic dysfunction, with mean incubation periods ranging from 35 to 49 d (Table 2). These rapid incubation periods were maintained upon serial passage of these prions in Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice (Table S2). In comparison, uninoculated Tg3581+/− and Tg3574+/− mice developed signs of neurologic dysfunction with mean incubation periods of 218 and 319 d, respectively (Table 1). Thus, inoculation of young Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice with brain homogenates from ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice accelerated the development of neurologic dysfunction considerably (Fig. 2 A and B), shortening the time to disease onset in Tg3574+/− mice by ∼70%.

Table 2.

Passage of brain homogenates from spontaneously ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice to Tg(BVPrP,I109), Tg(MoPrP)4053, and WT FVB mice

| Inoculum | Age at onset of spon. illness, d | Recipient line | Mean incubation period ± SEM, d | Signs of neurol. dysfunction, n/n0 | PK-resistant PrPSc, n/n0 |

| Spon. ill Tg3574+/− (i) | 266 | Tg(BVPrP,I109)S3574+/− | 47 ± 1 | 8/8 | 0/4 |

| Tg(BVPrP,I109)S3581+/− | 35 ± 1 | 8/8 | 0/4 | ||

| Tg(MoPrP)4053 | 292 ± 4 | 7/7 | 0/4 | ||

| Spon. ill Tg3574+/− (ii) | 371 | Tg(MoPrP)4053 | 74 ± 5* | 7/8 | 5/5 |

| Spon. ill Tg3581+/− (i) | 234 | Tg(BVPrP,I109)S3574+/− | 47 ± 1 | 8/8 | 0/4 |

| Tg(BVPrP,I109)S3581+/− | 38 ± 1 | 16/16 | 0/4 | ||

| Tg(MoPrP)4053 | 310 ± 15 | 8/8 | 0/4 | ||

| Spon. ill Tg3581+/− (ii) | 237 | Tg(BVPrP,I109)S3581+/− | 38 ± 2 | 8/8 | 0/4 |

| Tg(MoPrP)4053 | 344 ± 12 | 7/7 | 0/4 | ||

| Spon. ill Tg3581+/+ | 112 | Tg(MoPrP)4053 | 96 ± 7† | 5/7 | 4/4 |

| Spon. ill Tg3615+/− (i) | 171 | Tg(BVPrP,I109)S3574+/− | 49 ± 2 | 8/8 | 0/4 |

| Tg(BVPrP,I109)S3581+/− | 40 ± 2 | 8/8 | 0/4 | ||

| Tg(MoPrP)4053 | 132 ± 38 | 7/7 | 7/7 | ||

| FVB | 185 ± 8‡ | 6/8 | 6/6 | ||

| Spon. ill Tg3615+/− (ii) | 177 | Tg(MoPrP)4053 | 318 ± 21 | 8/8 | 0/4 |

| Spon. ill Tg3615+/− (iii) | 126 | Tg(MoPrP)4053 | 79 ± 7 | 8/8 | 5/5 |

n, number of positive mice; n0, number of examined mice. Lowercase Roman numerals identify unique samples from a given line.

*Mean incubation period calculated from seven ill mice; one mouse remains healthy, now at >312 d postinoculation (dpi).

†Mean incubation period calculated from five ill mice; two mice remain healthy, now at >249 dpi.

‡Mean incubation period calculated from six ill mice; two mice remain healthy, now at >300 dpi.

Fig. 2.

Rapid transmission of spontaneous disease to Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice. (A and B) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for Tg3581+/− (A) or Tg3574+/− (B) mice inoculated at ∼60 d of age with brain homogenate from the indicated spontaneously ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice. Uninoculated mice are shown for comparison. (C–H) Neuropathologic features of an inoculated Tg3574+/− mouse that developed signs of neurologic dysfunction at 47 d postinoculation (dpi) with brain homogenate from a spontaneously ill Tg3581+/− mouse (C–E) compared with an age-matched, uninoculated Tg3574+/− mouse (F–H). Spongiform degeneration (C), astrocytic gliosis (D), and punctate PrP deposition (E) were present in the hippocampus. In contrast, no spongiform degeneration (F), minimal GFAP staining (G), and no PrP deposition (H) were observed in an uninoculated Tg3574+/− mouse. (Scale bar in C–H, 100 μm.) cc, corpus callosum; CA1, CA1 layer of pyramidal neurons. (I) Immunoblotting for PrP in the brains of Tg3574+/− mice inoculated with brain homogenate from spontaneously ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice; these Tg3574+/− mice showed signs of neurologic dysfunction at 46–49 dpi and had increased levels of PTA-precipitable PrP and mildly PK-resistant PrP in their brains compared with age-matched, uninoculated mice. (J) Bioluminescence imaging (BLI) of the brains of uninoculated Tg(BVPrP:Gfap-luc)3581 mice (black, n = 9) and Tg(BVPrP:Gfap-luc)3581 mice inoculated with brain homogenate from a spontaneously ill Tg3581+/− mouse (red, n = 8). An increase in the BLI signal was apparent by 26 dpi.

Neuropathologic analysis of the brains of inoculated Tg3574+/− mice revealed prominent spongiform degeneration, astrocytic gliosis, and punctate PrP deposition (Fig. 2 C–E) compared with age-matched, uninoculated mice (Fig. 2 F–H). The brains of inoculated Tg3574+/− mice contained increased levels of PTA-precipitable PrP and mildly protease-resistant PrP compared with 2-mo-old, uninoculated Tg3574+/− mice (Fig. 2I); these findings are similar to observations in aged, spontaneously ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice (Fig. 1H). In addition, similar neuropathologic and biochemical features were observed in inoculated Tg3581+/− mice (Fig. S3). These results argue that prions were spontaneously generated in Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice, a process that can be accelerated by inoculating brain extracts from ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice into other mice expressing the same transgene.

To monitor the kinetics of disease progression following inoculation, we performed bioluminescence imaging (BLI) on bigenic mice expressing BVPrP and firefly luciferase (luc) under the control of the Gfap promoter. Previous studies using BLI on mice expressing Gfap-luc (27) enabled the visualization of neurologic disease in living mice before the appearance of clinical signs (28, 29). In inoculated Tg(BVPrP:Gfap-luc)3581 mice, an elevation in the brain BLI signal was apparent by 26 d postinoculation (Fig. 2J) and progressively increased until ∼35 d postinoculation when mice developed neurologic signs and were euthanized. The brain BLI signal from uninoculated Tg(BVPrP:Gfap-luc)3581 mice remained at background levels for the duration of the experiment (70 d).

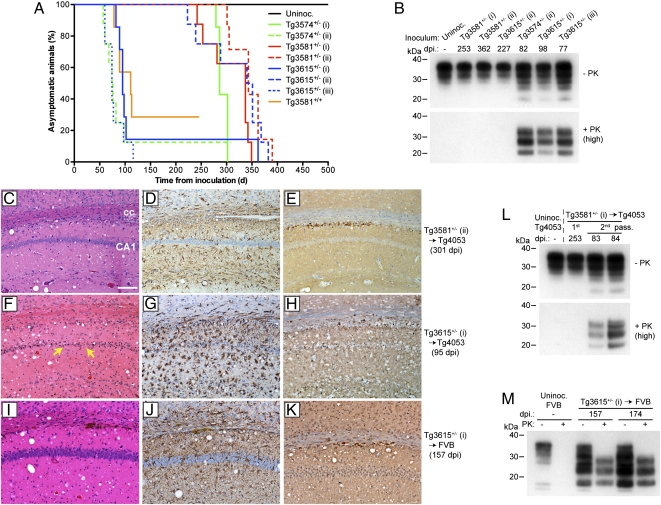

We next sought to determine whether the spontaneously generated prions in Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice could be transmitted to mice that do not develop spontaneous disease. For this purpose, we used Tg(MoPrP-A)4053 mice that express MoPrP-A at approximately four times compared with MoPrP in WT FVB mice; these mice are referred to as Tg4053 mice and do not develop spontaneous signs of neurologic illness with aging (30, 31). Brain homogenates from eight different spontaneously ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice were inoculated into Tg4053 mice (Table 2). All eight inocula transmitted to Tg4053 mice, with mean incubation periods falling into two distinct groups: (i) ∼100 d and (ii) ∼300 d (Fig. 3A). Immunoblotting revealed biochemical differences in PrP that accumulated in ill Tg4053 mice. PK-resistant PrP was observed in the brains of inoculated Tg4053 mice that exhibited incubation periods of ∼100 d (Fig. 3B). In contrast, Tg4053 mice with the longer incubation periods harbored no PK-resistant PrP in their brains. For all ill Tg4053 mice regardless of the incubation time, neuropathologic signs of prion disease were found in the brain, including spongiform degeneration, astrocytic gliosis, and punctate PrP deposition (Fig. 3 C–H). In the Tg4053 mice harboring PK-resistant PrP, the extent of neuronal loss and gliosis was greater than in Tg4053 mice harboring PK-sensitive PrP in their brains.

Fig. 3.

Transmission of spontaneous disease to Tg(MoPrP) and WT mice. (A) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for uninoculated Tg4053 mice and Tg4053 mice inoculated with brain homogenates from the indicated spontaneously ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice. (B) Immunoblots of PrP in ill Tg4053 mice inoculated with brain extracts of spontaneously ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice. Brain samples were left undigested (−) or digested with 50 μg/mL of PK (+). Tg4053 mice with incubation periods of <100 d showed PK-resistant PrP in their brains, whereas Tg4053 mice with incubation periods of >225 d showed no PK-resistant PrP. (C–K) Neuropathologic features of ill Tg4053 and FVB mice inoculated with spontaneously ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) brains. Spongiform degeneration (C, F, and I), astrocytic gliosis (D, G, and J), and punctate PrP deposition (E, H, and K) were observed in the brains of Tg4053 (C–H) or FVB (I–K) mice inoculated with brain homogenate from a spontaneously ill Tg3581+/− mouse (C–E) or a spontaneously ill Tg3615+/− mouse (F–K). Neuronal loss was apparent in the Tg4053 mouse inoculated with the Tg3615+/− brain extract (yellow arrows in F). The hippocampus is shown in all sections. (Scale bar in C–K, 100 μm.) cc, corpus callosum; CA1, CA1 layer of pyramidal neurons. (L) Immunoblot of PrP in ill Tg4053 mice after second passage of Tg(BVPrP,I109) brain extract. The brain extract used for inoculation was from a Tg4053 mouse with an incubation period of 253 d and harbored no PK-resistant PrP in its brain. Upon second passage, PK-resistant PrPSc accumulated in the brains of ill Tg4053 mice. (M) Immunoblot of PrP in the brains of two ill WT FVB mice inoculated with brain homogenate from a spontaneously ill Tg3615+/− mouse revealed PK-resistant PrPSc (50 μg/mL of PK).

Brain extracts were prepared from two ill Tg4053 mice and inoculated into additional Tg4053 mice for a second passage (Table S3). One inoculum was prepared from a Tg4053 mouse with a shorter incubation period (∼90 d) and PK-resistant PrP in its brain. The other inoculum was prepared from a Tg4053 mouse with a longer incubation period (>300 d) and no protease-resistant PrP in its brain. On second passage, both inocula transmitted prion disease to injected Tg4053 mice, with mean incubation periods of <115 d (Table S3). PK-resistant PrP was observed in all ill Tg4053 mouse brains examined by immunoblotting, including the mice inoculated with brain extract from the Tg4053 mouse that did not harbor PK-resistant PrP on first passage (Fig. 3L and Fig. S4).

To determine whether the prions generated spontaneously in the brains of Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice could also be transmitted to WT mice, we inoculated FVB mice with brain homogenate from a spontaneously ill Tg3615+/− mouse. Inoculation of FVB mice resulted in neurologic dysfunction in six of eight inoculated mice with a mean incubation period of 185 d (Table 2). Analysis of the brains of inoculated FVB mice revealed neuropathologic changes characteristic of prion disease as well as stereotypical PK-resistant PrP (Fig. 3 I–K and M-), arguing that PrP overexpression was not required for transmission. Cumulatively, these results argue that infectious prions were generated spontaneously in the brains of Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice and that these prions were transmissible to mice expressing WT MoPrP.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate the spontaneous generation of prions in mice expressing a WT PrP sequence. Spontaneous neurodegeneration has not been reported in Tg mice overexpressing WT hamster, sheep, cow, human, or elk PrP. Thus, the spontaneous disease observed in Tg(BVPrP) mice is unlikely to be due to the expression of a nonmouse PrP molecule within the mouse brain. Although PrPSc-like conformations have been induced by expression of WT PrP in the cytosol, these PrP conformations have not been shown to be infectious (32). The spontaneous generation of prions has also recently been observed in Tg mice expressing MoPrP lacking its GPI anchor (26). However, these mice express a non–membrane-anchored, mutant PrP molecule that is associated with a familial, but not sporadic, prion disease in humans (33). The prions generated spontaneously from WT and presumably membrane-anchored PrP in the brains of Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice and their transmissibility to WT mice argue that Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice may be an excellent model for studying the factors responsible for the sporadic forms of prion disease including sCJD. In previous studies, Tg mice expressing mouse or human PrP containing mutations linked to familial prion diseases exhibited some neuropathologic or clinical symptoms reminiscent of prion disease, but the disease was not generally transmissible to mice expressing WT MoPrP (10–14). Tg mice expressing a chimeric elk/mouse PrP also developed spontaneous neurologic illness (34), which could be transmitted to tga20 mice overexpressing MoPrP at approximately sevenfold levels and resulted in the production of PK-resistant prions, but only after three rounds of serial passaging.

Similar to the structure of elk/mouse PrP expressed in the Tg mice described above (34), BVPrP contains a rigid loop within the β2–α2 loop region of its structure (Fig. S1) (35). This region of PrP is surmised to influence the interspecies transmission of prions (36), and expression of a chimeric horse/mouse PrP molecule containing a rigid loop in Tg mice resulted in a spongiform encephalopathy (37). Therefore, the rigid loop region of BVPrP may be important for promoting spontaneous prion formation. However, BVPrP(M109) also contains a rigid loop, and Tg(BVPrP,M109) mice expressing equivalent or higher levels of PrP than Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice did not develop spontaneous neurologic illness. Thus, expression of isoleucine at position 109 seems to be critical for the spontaneous generation of prions. Codon 109 in BVPrP corresponds to residue 108 of MoPrP, which is also polymorphic (Fig. S1) and known to influence the transmission rates of prions (38, 39). This residue lies within the vicinity of PrP regions known to modulate the generation of transmembrane topological variants of the protein, which cause nontransmissible neurologic illnesses in Tg mice (40). The precise residues of BVPrP that are responsible for the spontaneous generation of prions remain to be determined.

The observation that Tg4053 mice infected with brain extracts of ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice exhibited two distinct ranges of incubation times showed that at least two different prion strains were generated. Notably, the strains enciphering shorter incubation times contained protease-resistant PrPSc, whereas those strains with longer incubations were composed of protease-sensitive PrPSc. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that the “fast,” protease-resistant strains are present at low titers in the brains of spontaneously ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice, but propagate more rapidly upon passage in Tg4053 or WT mice. In contrast, the “slower,” protease-sensitive strains likely accumulate to higher titers in spontaneously ill Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice and are able to infect young Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice rapidly, but propagate more slowly in Tg4053 mice. A second possibility is that the two distinct strains emerge in a stochastic manner following cross-species transmission of a single protease-sensitive BVPrPSc strain. Whether the protease-sensitive strains influence or are required for the generation of the protease-resistant strains is currently unknown. Interestingly, the protease-sensitive strains are sufficient to elicit all of the neuropathologic hallmarks of prion disease. Thus, Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice may be useful for isolating neurotoxic prion assemblies, including the hypothetical oligomeric PrPL (“PrP lethal”) species (41, 42).

Whereas spontaneous prion disease has not been reported in bank voles, it is conceivable that older bank voles may potentially harbor subclinical doses of prions in their brains. In WT voles, spontaneous prion formation is likely to be stochastic in nature and will occur more infrequently in animals with physiologic levels of PrP expression, not overexpressed as in the Tg(BVPrP,I109) mice described here. Therefore, spontaneous prion disease may not manifest within the normal lifespan of the animal. Alternatively, bank voles may have evolved compensatory mechanisms to deal with the increased propensity for PrP misfolding. When the increased potential for BVPrP to misfold spontaneously is coupled with the high susceptibility of bank voles for diverse prion isolates including scrapie and chronic wasting disease (17–19), it is possible that voles may constitute a substantial and renewing environmental source of prions.

The abbreviated incubation times observed in Tg(BVPrP) mice inoculated with spontaneously formed Tg(BVPrP,I109) prions (diagnosis at ∼25 d postinoculation by bioluminescence imaging or ∼35 d postinoculation by the onset of clinical symptoms) should herald substantial progress in our understanding of the prion diseases. In the past, reductions in the time required to bioassay prions have produced important advances in prion biology. The ability to bioassay prions in 4 to 5 wk should facilitate our understanding of prion replication, increase our knowledge of strain generation, and accelerate the development of effective therapeutics for prion disease.

Methods

Additional methods are provided in SI Methods.

Mice.

All mice used in this study were maintained on an FVB/Prnp0/0 genetic background except WT FVB mice and Tg(MoPrP)4053 mice overexpressing MoPrP (30), which were maintained on a WT Prnp+/+ background. All animal experiments were performed under protocols approved by the institutional animal care and use committee at the University of California, San Francisco.

Generation of Transgenic Mice.

The bank vole PrP (BVPrP) ORF encoding methionine at codon 109 (GenBank accession nos. AF367624.1 and EF455012.1) was synthesized and then amplified with flanking SalI restriction sites by PCR using the primers 5′-CTATATGTCGACACCATGGCGAACCTCAGCTAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTATATGTCGACTCATCCCACGATCAGGAAGAT-3′ (reverse). Following SalI digestion, the BVPrP coding sequence was inserted into SalI-digested and dephosphorylated cos.Tet vector (43), which drives neuronal expression using the hamster Prnp promoter. Isoleucine was introduced at the BVPrP codon 109 polymorphism by site-directed mutagenesis and then inserted into cos.Tet. Vectors containing BVPrP constructs were linearized by digestion with NotI, purified, and then microinjected into the pronuclei of fertilized eggs obtained from FVB/Prnp0/0 mice. Southern blotting of genomic DNA samples was used to identify potential founder animals, and the sequences of the integrated transgenes were verified by DNA sequencing. Tg(BVPrP) lines were maintained in a hemizygous state (denoted +/−) by backcrossing to Prnp0/0 mice. Homozygous pups (denoted +/+) were generated by intercrossing hemizygous mice and identified by quantitative Southern blotting.

Tg(BVPrP) mice were monitored daily for routine health and assessed three times per week for neurologic dysfunction. Mice were euthanized following the onset of neurologic signs based on standard diagnostic criteria (44). Brains were then removed and either snap frozen before storage at −80 °C for biochemical analysis or fixed in formalin for neuropathologic analysis.

Digestion of Proteins with Proteinase K.

For PK digestions, brains were homogenized to 10% (wt/vol) in PBS and then subjected to detergent extraction using 0.5% sodium deoxycholate/0.5% Nonidet P-40. Protein concentrations were normalized using the bicinchoninic acid assay and then 200 μg of detergent-extracted protein was prepared in 60 μL PBS containing 50 μg/mL PK (PK:protein ratio of 1:67) for standard (denoted as “high” PK) conditions or 3 μg/mL PK for mild (denoted as “low” PK) conditions. Digestions were performed at 37 °C for 1 h and then stopped by the addition of NuPAGE sample buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol and subsequent boiling. PK-digested samples were then subjected to immunoblotting using the anti-PrP antibodies HuM-P (45) or HuM-D18 (46).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the Hunter's Point animal facility for their assistance with the animal experiments, Marta Gavidia for mouse genotyping, and Ana Serban for recombinant protein and antibodies. The Tg(Gfap-luc) mice were a generous gift from Caliper Life Sciences. This work was supported by Grants from the National Institutes of Health (AG02132, AG10770, AG021601, AG031220, AI064709, and NS041997) as well as by gifts from the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation, Sherman Fairchild Foundation, Schott Foundation for Public Education, and Rainwater Charitable Foundation. J.C.W. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1121556109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Colby DW, Prusiner SB. Prions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a006833. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–144. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li M, et al. Widespread RNA and DNA sequence differences in the human transcriptome. Science. 2011;333:53–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1207018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deleault NR, Harris BT, Rees JR, Supattapone S. Formation of native prions from minimal components in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:9741–9746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702662104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colby DW, et al. Design and construction of diverse mammalian prion strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20417–20422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910350106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makarava N, et al. Recombinant prion protein induces a new transmissible prion disease in wild-type animals. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:177–187. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0633-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang F, Wang X, Yuan C-G, Ma J. Generating a prion with bacterially expressed recombinant prion protein. Science. 2010;327:1132–1135. doi: 10.1126/science.1183748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edgeworth JA, et al. Spontaneous generation of mammalian prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14402–14406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004036107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsiao KK, et al. Spontaneous neurodegeneration in transgenic mice with mutant prion protein. Science. 1990;250:1587–1590. doi: 10.1126/science.1980379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Telling GC, et al. Interactions between wild-type and mutant prion proteins modulate neurodegeneration in transgenic mice. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1736–1750. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.14.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiesa R, Piccardo P, Ghetti B, Harris DA. Neurological illness in transgenic mice expressing a prion protein with an insertional mutation. Neuron. 1998;21:1339–1351. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80653-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dossena S, et al. Mutant prion protein expression causes motor and memory deficits and abnormal sleep patterns in a transgenic mouse model. Neuron. 2008;60:598–609. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson WS, et al. Spontaneous generation of prion infectivity in fatal familial insomnia knockin mice. Neuron. 2009;63:438–450. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman-Levi Y, et al. Fatal prion disease in a mouse model of genetic E200K Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002350. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 15.Asante EA, et al. Absence of spontaneous disease and comparative prion susceptibility of transgenic mice expressing mutant human prion proteins. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:546–558. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.007930-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitamoto T, Tateishi J, Sawa H, Doh-Ura K. Positive transmission of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease verified by murine kuru plaques. Lab Invest. 1989;60:507–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nonno R, et al. Efficient transmission and characterization of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease strains in bank voles. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e12. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agrimi U, et al. Prion protein amino acid determinants of differential susceptibility and molecular feature of prion strains in mice and voles. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000113. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heisey DM, et al. Chronic wasting disease (CWD) susceptibility of several North American rodents that are sympatric with cervid CWD epidemics. J Virol. 2010;84:210–215. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00560-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cartoni C, et al. Identification of the pathological prion protein allotypes in scrapie-infected heterozygous bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus) by high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2005;1081:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Will RG, et al. A new variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in the UK. Lancet. 1996;347:921–925. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watts JC, et al. Protease-resistant prions selectively decrease shadoo protein. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002382. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilham JM, et al. Rapid end-point quantitation of prion seeding activity with sensitivity comparable to bioassays. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001217. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsiao KK, et al. Serial transmission in rodents of neurodegeneration from transgenic mice expressing mutant prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9126–9130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nazor KE, et al. Immunodetection of disease-associated mutant PrP, which accelerates disease in GSS transgenic mice. EMBO J. 2005;24:2472–2480. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stöhr J, et al. Spontaneous generation of anchorless prions in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:21223–21228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117827108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu L, et al. Non-invasive imaging of GFAP expression after neuronal damage in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2004;367:210–212. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamgüney G, et al. Measuring prions by bioluminescence imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15002–15006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907339106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watts JC, et al. Bioluminescence imaging of Abeta deposition in bigenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2528–2533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019034108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlson GA, et al. Prion isolate specified allotypic interactions between the cellular and scrapie prion proteins in congenic and transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5690–5694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colby DW, et al. Protease-sensitive synthetic prions. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000736. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma J, Lindquist S. Conversion of PrP to a self-perpetuating PrPSc-like conformation in the cytosol. Science. 2002;298:1785–1788. doi: 10.1126/science.1073619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jansen C, et al. Prion protein amyloidosis with divergent phenotype associated with two novel nonsense mutations in PRNP. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:189–197. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0609-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sigurdson CJ, et al. De novo generation of a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy by mouse transgenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:304–309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810680105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christen B, Pérez DR, Hornemann S, Wüthrich K. NMR structure of the bank vole prion protein at 20 degrees C contains a structured loop of residues 165-171. J Mol Biol. 2008;383:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sigurdson CJ, et al. A molecular switch controls interspecies prion disease transmission in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2590–2599. doi: 10.1172/JCI42051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sigurdson CJ, et al. Spongiform encephalopathy in transgenic mice expressing a point mutation in the β2-α2 loop of the prion protein. J Neurosci. 2011;31:13840–13847. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3504-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moore RC, et al. Mice with gene targetted prion protein alterations show that Prnp, Sinc and Prni are congruent. Nat Genet. 1998;18:118–125. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barron RM, et al. Polymorphisms at codons 108 and 189 in murine PrP play distinct roles in the control of scrapie incubation time. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:859–868. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80525-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hegde RS, et al. A transmembrane form of the prion protein in neurodegenerative disease. Science. 1998;279:827–834. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collinge J, Clarke AR. A general model of prion strains and their pathogenicity. Science. 2007;318:930–936. doi: 10.1126/science.1138718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sandberg MK, Al-Doujaily H, Sharps B, Clarke AR, Collinge J. Prion propagation and toxicity in vivo occur in two distinct mechanistic phases. Nature. 2011;470:540–542. doi: 10.1038/nature09768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scott MR, Köhler R, Foster D, Prusiner SB. Chimeric prion protein expression in cultured cells and transgenic mice. Protein Sci. 1992;1:986–997. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560010804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carlson GA, et al. Genetics and polymorphism of the mouse prion gene complex: Control of scrapie incubation time. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:5528–5540. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.12.5528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Safar JG, et al. Measuring prions causing bovine spongiform encephalopathy or chronic wasting disease by immunoassays and transgenic mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:1147–1150. doi: 10.1038/nbt748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williamson RA, et al. Mapping the prion protein using recombinant antibodies. J Virol. 1998;72:9413–9418. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9413-9418.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.