Abstract

Humans extensively help others altruistically, which plays an important role in maintaining cooperative societies. Although some nonhuman animals are also capable of helping others altruistically, humans are considered unique in our voluntary helping and our variety of helping behaviors. Many still believe that this is because only humans can understand others’ goals due to our unique “theory of mind” abilities, especially shared intentionality. However, we know little of the cognitive mechanisms underlying helping in nonhuman animals, especially if and how they understand others’ goals. The present study provides the empirical evidence for flexible targeted helping depending on conspecifics’ needs in chimpanzees. The subjects of this study selected an appropriate tool from a random set of seven objects to transfer to a conspecific partner confronted with differing tool-use situations, indicating that they understood what their partner needed. This targeted helping, (i.e., selecting the appropriate tool to transfer), was observed only when the helpers could visually assess their partner's situation. If visual access was obstructed, the chimpanzees still tried to help their partner upon request, but failed to select and donate the appropriate tool needed by their partner. These results suggest that the limitation in chimpanzees’ voluntary helping is not necessarily due to failure in understanding others’ goals. Chimpanzees can understand conspecifics’ goals and demonstrate cognitively advanced targeted helping as long as they are able to visually evaluate their conspecifics’ predicament. However, they will seldom help others without direct request for help.

Keywords: altruism, prosocial behavior, instrumental helping, empathy, behavioral flexibility

Humans extensively help others altruistically, which plays an important role in maintaining cooperative societies. How have humans evolutionarily achieved this cooperative trait? Many theoretical studies have provided ultimate explanations for the evolution of altruism and cooperation. These studies have indeed addressed the “why,” but not the “how.” Many nonhuman animals demonstrate cooperative abilities (1–3), and recent empirical studies have also revealed that some nonhuman primates can help or share food with conspecifics without any direct benefit to themselves [e.g., cotton-top tamarin (Saguinius oedipus) (4); capuchin (Cebus appella) (5–7); marmoset (Callitrix jacchus) (8); bonobo (Pan paniscus) (9); and chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) (10–14)]. However, our understanding of the cognitive mechanisms involved remains limited and urgently requires further investigation, especially from a comparative perspective.

Regarding the cognitive mechanisms involved in helping, much focus has been given to “targeted helping” [also known as “instrumental helping” (10, 11)], which is defined as help and care based on the cognitive appreciation of the need or situation of others (15). Targeted helping is considered to be linked to the cognitive capacity for empathy. Among nonhuman animals, only some great ape, cetacean, and elephant species demonstrate this form of helping behavior (15). By definition, the animals are expected to understand the others’ needs. However, to date, empirical studies clearly demonstrating this cognitive ability in nonhuman animals are lacking. If and how the animals understand the others’ goals and help others effectively are core questions that have to be examined if we are ever to deepen our understanding of the evolution of cooperation.

Among those animal species known to demonstrate targeted helping, chimpanzees, one of our closest living relatives, help others upon request, but seldom voluntarily in contexts requiring assistance provisioning (12, 13). This concurs with observations of food sharing among chimpanzees in the wild (16, 17). Interestingly, in our previous experiments (12), observation of a conspecific in trouble did not elicit chimpanzees’ helping behavior. A recent study has documented chimpanzees’ spontaneous generosity in a prosocial choice test (14). Other studies, however, indicate that chimpanzees fail to give food spontaneously to a conspecific even at no cost to themselves (18–20), between a mother and her infant (21–23), and in reciprocal contexts (21, 22, 24, 25). Direct request, (e.g., an out-stretched arm directed at a potential helper, may be required to prompt targeted helping in chimpanzees) (26).

Why do chimpanzees seldom help others without being requested? One plausible explanation from the perspective of cognitive mechanisms is that chimpanzees cannot understand another's goal upon witnessing another's predicament. Many still believe that humans are unique in this respect because we are the only animal species endowed with unique “theory of mind” abilities enabling us to understand the goals and to share the intentions of others (27). Warneken and Tamasello (10) empirically demonstrated that chimpanzees, compared with humans, have a limited range of helping behaviors and suggest that this is because of the inability of chimpanzees to interpret what others need in different situations. Nevertheless, we still know little about the cognitive mechanisms underlying helping behavior in nonhuman animals, and no study has empirically examined if and how chimpanzees understand others’ goals in these types of helping contexts.

We developed an experimental paradigm aimed at examining chimpanzees’ ability and flexibility in effectively helping a conspecific depending on his/her specific needs. This experiment required participants to select and transfer an appropriate tool to a conspecific partner so that he or she could solve a task to obtain a juice reward. We set up one of two tool-use situations: a stick-use situation or a straw-use situation in the potential recipient's booth. Seven objects, including a stick and a straw (Fig. 1), were supplied on a tray in an adjacent booth occupied by a potential helper. The potential recipient could not directly reach any of the tools available in the adjoining booth, but could demonstrate a request by poking his or her arm through a hole in the panel wall separating the two booths. In previous experimental studies (10–13), a potential helper was never confronted with a behavioral choice when given the opportunity to help. These previous experiments therefore failed to examine whether chimpanzees actually understood what others needed. In our study, the helper had to select a tool from an array of seven objects to effectively help his or her partner accomplish the task with which he or she was confronted. We also developed and compared two conditions in which a potential helper could or could not see the partner's tool-use situation. Our study highlights notable cognitive mechanisms underlying helping behavior in chimpanzees.

Fig. 1.

Tool set consisting of seven objects that were supplied to a potential helper. Only one of them (a stick or a straw) was needed for a conspecific to solve either a stick-use or straw-use task in the adjoining booth.

The setup of the present study is fairly similar to previous experiments conducted by Savage-Rumbaugh and colleagues (28). However, there are clear differences between this latter study and our own. In Savage-Rumbaugh and colleagues' study, the two chimpanzee participants correctly chose and donated tools that their partner requested using symbols. This study significantly promoted our understanding of symbolic communication abilities in chimpanzees; however, it provided limited insight into their helping behavior and its mechanisms. In addition, pretest training artificially shaped the subjects’ symbolic communication and also their giving and sharing interactions. The potential recipient chimpanzees were trained to indicate which tool they needed by selecting a corresponding lexigram, and the potential donors were trained to select and transfer the tool corresponding to the presented lexigram. The performances were established through standard fading, shaping, chaining, and discrimination procedures, as also used in studies with pigeons (29). To eliminate these possibilities, we developed significantly different procedures. First, although the chimpanzees were all trained in solving the two tool-use tasks presented to them, the experimenter never performed any other type of training or shaping of behavior of the participants. Second, we allowed our subjects to communicate with each other without symbols or any other form of artificial communication medium. With these modifications, we investigated how chimpanzees understand what others require on the basis of their natural communicative abilities and whether or not they can flexibly and spontaneously modify their helping behavior according to others’ needs.

Results and Discussion

First “Can See” Condition.

We first tested the chimpanzees in a “can see” condition, where the panel wall was transparent so that a potential helper could see his or her partner's tool-use situation in the adjacent booth. Overall, object offer (at least one object regardless of whether it was a tool or a nontool object) from potential helpers was observed on average in 90.8% (n = 5, SEM = 3.4) of trials. In the familiarization phase before testing (eight 5-min trials for each participant), where the chimpanzees could freely manipulate the seven objects without any tool-use situation, object offer was observed in only 5.0% (n = 5, SEM = 3.1) of trials, suggesting that the chimpanzees were not motivated to transfer objects to their partner when no tool task was available. Object offer occurred mainly following the recipient's request. An “upon-request offer” accounted for 90.0% (n = 5, SEM = 5.7) of all offers. This result concurs with previous findings that direct request is important for the onset of targeted helping in chimpanzees (12, 13, 26).

The chimpanzees, except the chimpanzee Pan, first offered potential tools (a stick or a straw) significantly more frequently than the other nontool objects (Ai: 87.5%; Cleo: 97.4%; Pal: 93.5%; Ayumu: 78.0%; Fisher's exact test: P < 0.05 for each of these four participants, with a chance level set at 50% due to the binary choice between tool and nontool objects; see Table S1 for the individual details). In Pan's case, she most frequently offered a nontool brush (79.5% of her first object offers). When we eliminated the brush offer from the analysis, her offer of the potential tools was also significantly above chance level (88.6%; Fisher's exact test: P < 0.01 with a chance level set at 50%). This bias toward offering a stick and a straw suggests that the chimpanzees distinguished the potential tools from the other useless objects. The chimpanzees’ prior experience with these tools in previous experiments may explain this bias (12).

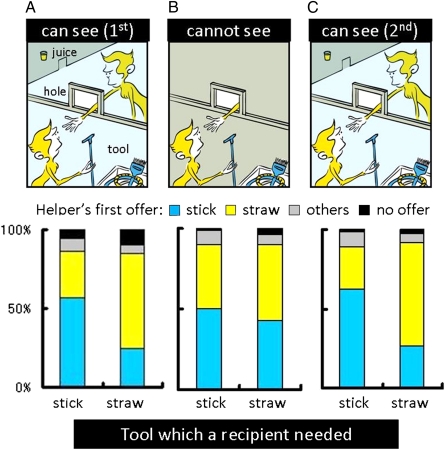

We then examined the chimpanzees’ first offer, limiting our analysis to stick or straw tool transfers only. Among four of the five chimpanzee participants whom we tested, there was a significant difference in the first offer between the partner's two tool-use situations (Fisher's exact test: P < 0.05 for each of the four participants; see Table 1 for details). Helpers selected to offer more frequently a stick (or a straw) when their partner was confronted with the stick-use (or the straw-use) situation than when he or she was faced with the straw-use (or the stick-use) situation (Fig. 2A; Movie S1; see Table S1 for individual details). Therefore, the chimpanzees demonstrated flexible targeted helping depending on their partner's predicaments. This result suggests that the chimpanzees understood which tool their partner required to solve successfully the tool-use task with which he or she was confronted.

Table 1.

P values of Fisher's exact test (two-tailed) comparing each participant's first-offer ratio of stick and straw tools between the two tool-use situations presented in the recipient's booth

| Chimpanzee | “Can see” (first) | “Cannot see” | “Can see” (second) |

| Ai | 0.015 | 0.54 | 0.008 |

| Cleo | 0.031 | 0.61 | <0.001 |

| Pal | 0.008 | 0.084 | 0.002 |

| Ayumu | 0.004 | <0.001 | — |

| Pan | 0.48 | 0.44 | — |

Values in boldface type indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Helpers’ first tool selection and offer to their conspecific partner. Each condition [(A) first “can see”, (B) “cannot see”, and (C) second “can see” condition] presented participants in the recipient booth with one of two tool-use situations (“stick” or “straw”). Graphs are based on the data from three participants (Ai, Cleo, and Pal) who completed all of the conditions based on an A–B–A design. For the statistical analysis, see Table 1.

“Cannot See” Condition.

To investigate how the chimpanzees understood which tool their partner required, we next developed the “cannot see” condition. In this condition, the panel wall was opaque so that a potential helper could not readily see his or her partner's tool-use situation unless he or she purposely stood up and peaked through a hole ∼1 m above the floor. In this condition, the chimpanzees continued to help, offering at least one object (regardless of whether a tool or nontool) in 95.8% of trials on average (n = 5, SEM = 1.9). There was no significant difference in the frequency of object offer between the previous “can see” condition and this “cannot see” condition (paired t test (two-tailed): t = −2.1, df = 4, P = 0.099). Upon-request offer (71.7%, n = 5, SEM = 18.3) again predominated over “voluntary offer” (28.3%, n = 5, SEM = 18.3), although the ratio of voluntary offer significantly increased from the previous “can see” condition in two individuals (Ayumu and Cleo; Fisher's exact test: P < 0.05). This increase in voluntary offer was likely due to a carryover effect from the previous condition. The helper had possibly learned that he or she was expected to offer an object to his or her partner under this new experimental condition.

As in the “can see” condition, the chimpanzees, except Pan, first offered potential tools (a stick or a straw) significantly more frequently than the other nontool objects (Ai: 89.4%; Cleo: 88.9%; Pal: 100%; Ayumu: 93.0%; Fisher's exact test: P < 0.01 for each of these four participants with a chance level set at 50%). Pan again showed a particular preference for offering a brush (55.3% of her first object offer); however, when we eliminated brush offer from the analysis, her offer of the potential tools was also significantly above chance level (100%; Pearson χ2 test: P < 0.01 with a chance level set at 50%).

The most important and suggestive difference between the “can see” and “cannot see” conditions appeared when we examined which tool—a stick or a straw—the chimpanzees offered first and compared this with the two tool-use situations presented in the partner's booth. Contrary to the “can see” condition, where we found a significant difference in stick/straw choice depending on the partner's predicament, such a difference disappeared in the “cannot see” condition in all participants except one subject (see Table 1 for statistics). Ayumu was the only individual who selected the appropriate tool even in the “cannot see” condition; he stood up and assessed his partner's situation by peaking through the hole before selecting and transferring the appropriate tool (Fig. 3). Therefore, for Ayumu, the “cannot see” condition was equivalent to the “can see” condition. However, the chimpanzees who did not visually assess their partner's situation in the “cannot see” condition failed to select and offer the appropriate tool needed by their partner (Fig. 2B; Movie S2; see Table S1 for individual details).

Fig. 3.

Photo showing Ayumu standing up and assessing his mother's situation by peaking through the hole in the opaque panel wall separating the two booths. He was the only chimpanzee to assess so actively his partner's situation and to select and transfer the appropriate tool to his partner in the “cannot see” condition.

The chimpanzee helpers understood their partner's goals only when they could visually appreciate their partner's situation. Potential recipients performed request behavior similarly in form and frequency in the “cannot see” condition and in the “can see” condition [mean percentage of trials in which a request was observed: “can see”—85.0%, n = 5, SEM = 7.3; “cannot see”—71.3%, n = 5, SEM = 18.1; paired t test (two-tailed)—t = 1.1, df = 4, P = 0.35]. Therefore, chimpanzee request behavior on its own failed to convey any reliable information on the requester's specific needs, (i.e., the appropriate tool needed). This means that, although request behavior might elicit the onset of chimpanzee helping, it is insufficient on its own for effective targeted helping. Ayumu's behavior, (i.e., selecting and transferring the appropriate tool after assessing his partner's situation by peaking through the hole), further demonstrates that the chimpanzees depended on visual assessment of their partner's situation to acquire the necessary information to appropriately help their partner.

Second “Can See” Condition.

To confirm that the difference in appropriate tool selection between the two conditions (significant difference in the “can see” condition and nonsignificant in the following “cannot see” condition for three of the participants) was not due to the experimental order of the two conditions, we repeated the “can see” condition for these three participants. We observed object offer in 97.9% (n = 3, SEM = 0.93) of the trials, and upon-request offer accounted for 79.4% (n = 3, SEM = 3.2) of all offers. The three chimpanzees first offered potential tools (a stick or a straw) significantly more frequently than the other nontool objects (Ai: 81.3%; Cleo: 95.7%; Pal: 100%; Fisher's exact test: P < 0.01 for each of these three participants with a chance level set at 50%). As in the first “can see” condition but not in the “cannot see” condition, we again confirmed a significant difference in the chimpanzees’ first offer of a stick or a straw depending on the partner's tool-use situations (Fisher's exact test: P < 0.01 for each of the three participants; see Table 1 for details). The three participants significantly more frequently selected and transferred a stick (or a straw) when their partner was confronted with the stick-use (or the straw-use) situation than when the partner was faced with the straw-use (or the stick-use) situation (Fig. 2C; see Table S1 for individual details). This confirms that the chimpanzees demonstrated flexible targeted helping with an understanding of which tool their partner needed when they could visually assess their partner's situation.

General Discussion.

This study provides the empirical evidence for chimpanzees’ flexible targeted helping based on an understanding of others’ goals. When helpers could visually assess their partner's predicament, they selected out of seven objects an appropriate tool to transfer to their partner so he or she could obtain a reward. This kind of targeted helping is cognitively advanced; it is clearly neither a programmed behavior nor an automatic stimulus response. Even without shared intentionality and sophisticated communicative skills, such as language or pointing, chimpanzees can understand others’ goals when situations are visibly obvious and understandable.

The present study also offers insights into the cognitive mechanisms underlying helping behavior in chimpanzees. First, chimpanzees are motivated to help others upon request even when they cannot properly assess the others’ predicament. Our results show that, even if visually prevented from understanding their partner's needs, the chimpanzees persisted in helping their partner upon request, although their tool choice often failed to correspond to their partners’ requirements (Movie S2). Although Pan failed to choose an appropriate tool on first offer even in the “can see” condition, she persisted in offering objects to her partner upon request. It is clear that all chimpanzees, including Pan, were motivated to respond to their partner's request. Second, even when chimpanzees understand the needs of others, they seldom help others unless directly requested. Our results also suggest that chimpanzees are able to understand what others need by simply witnessing the situation. Therefore, the limitation in chimpanzees’ voluntary helping (10–13, 18–25) cannot solely be explained by a failure in understanding others’ goals. Chimpanzees may not provide assistance to others unless requested despite being able to understand others’ goals. Combining these two points, we suggest that both understanding of others’ goals and detection of directed request are essential prerequisites in eliciting targeted helping in chimpanzees.

A crucial question for future research is to investigate similarities and differences in targeted helping and its mechanisms among humans, chimpanzees, and other nonhuman animals. In humans, sometimes only observing others in trouble seems to suffice to prompt the onset of helping even without directed request (e.g., spontaneous donation to disaster victims); however, the prevalence of this form of helping in humans remains debated. A recent study on human toddlers’ prosocial behavior (30) revealed that 18-mo-old infants helped an unfamiliar adult in trouble, but required considerable communication from the adult about his or her needs. Meanwhile, 30-mo-old infants helped an adult more spontaneously, possibly due to their acquired empathic abilities. The authors suggested that toddlers’ helping develops with their abilities to understand others’ subjective internal states. The chimpanzees’ helping behavior in the present study was fairly similar to that of the 18-mo-old toddlers. However, our results showed that chimpanzees helped others upon request even without proper knowledge of the others’ needs and also seldom helped others unless being requested even when they understood the others’ goals. In this respect, humans and chimpanzees might differ in the onset mechanisms involved in prompting helping behavior.

It is still too early to make any firm conclusions on similarities and differences in helping behavior and its mechanisms between humans and chimpanzees because of the lack of proper and rigorous comparative studies. In previous studies with human infants (10, 30), the experimenters (recipients of infants’ helping) expressed their needs not only by gesture but also by using language. This might prevent direct comparison between humans and nonhuman animals. The previous studies also did not clearly distinguish expression of desire and demonstration of request directed toward the potential helpers, which confounds any evaluation of how the toddlers understood the others’ goals. The present study proposes a rigorous, potentially comparative methodology and perspectives for studying mechanisms of targeted helping. Further comparative studies with humans, chimpanzees, and other nonhuman animals, especially bonobos, who also demonstrate considerable helping and cooperative behavior (9, 31), will no doubt shed further light on the evolution of targeted helping.

Materials and Methods

Participants were socially housed chimpanzees at the Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University. All participants had previously taken part in a variety of perceptual and cognitive studies, including experiments that examined their helping behavior in a similar setting as the present study (12). We tested five chimpanzees paired with kin (two mothers, Ai and Pan, were paired with their offspring, Ayumu and Pal, respectively, and three juveniles, Ayumu, Pal, and Cleo, were paired with their mothers, Ai, Pan, and Chloe, respectively) because these kin pairs demonstrated frequent tool-giving interactions in previous experiments (12). All participants were experts at the two tool-use tasks presented in the current study. The present study was approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University, and the chimpanzees were tested and cared for in accordance with the guide produced by the Animal Care Committee of the Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University (32).

The paired chimpanzee participants were tested in two adjacent experimental booths (136 × 142 cm and 155 × 142 cm; 200 cm high). A hole (12.5 × 35 cm) in the panel-wall divider separating the two participants was located ∼1 m above the floor. Each participant acted as either a potential helper or a potential recipient. We set up one of either two tool-use situations (the stick-use situation or the straw-use situation) in the recipient's booth (for details see ref. 12) and supplied in the helper's booth seven objects (a stick, a straw, a hose, a chain, a rope, a brush, and a belt) randomly presented on a tray (26 × 36 cm) (Fig. 1). Only one of the seven objects (a stick or a straw) could serve as an effective tool to successfully obtain the juice reward under either tool-use situation. To ensure that the chimpanzees were equally familiar with these seven objects, before testing we carried out a familiarization phase of eight 5-min trials (one trial a day) where the participants could freely manipulate these objects in the experimental booth without any tool-use situation.

We developed two conditions: the “can see” condition (as the test) in which the panel wall between the two booths was transparent and the “cannot see” condition (as the control) in which the panel wall was opaque. In the latter condition, helpers could not readily see which tool-use situation their partner was faced with, unless he or she purposely stood up and peaked through the hole. In either condition, chimpanzees could transfer objects or poke their arm through the hole. We first conducted 48 trials (random order of 24 trials of the stick-use and 24 trials of the straw-use situations) of the “can see” condition. Thereafter, we carried out 48 trials of the “cannot see” condition and again 48 trials of the “can see” condition if participants’ performance differed between the first “can see” and “cannot see” conditions. A trial started when we supplied the helper's booth with the tray loaded with the seven objects and ended either when the recipient succeeded in obtaining the juice reward upon being offered the appropriate tool or when 5 min had passed without appropriate tool transfer. We conducted two or four trials per day.

We recorded the participants’ behaviors and interactions with three video cameras (Panasonic NV-GS150) and analyzed what object the helper offered the recipient (see also ref. 12). We counted a helper's “offer” when a participant held out a tool toward a recipient, whether the recipient actually received it or not. Only the helper's first offer was retained for analysis. We categorized object offer into two types: upon-request offer and voluntary offer. With the upon-request offer, the giver offered a tool to the recipient upon the recipient's request. With the voluntary offer, the giver actively offered a tool to the recipient without the recipient's explicit request. When a tool was taken away by the recipient without the owner's offer (tolerated-theft transfer), this transfer was categorized as “no offer.” We counted a recipient's “request” when the recipient poked an arm through the hole. We used paired t test (two-tailed) to compare the chimpanzees’ averaged performance between the two experimental conditions and Fisher's exact test (two-tailed) to individually compare the rates of a helper's performance between two categorical variables.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Matsuzawa, T. Hasegawa, M. Tomonaga, Y. Hattori, C. Martin, and other staff members at the Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University, for their helpful advice and assistance with the present study. Thanks also to B. Hare and anonymous reviewers for thoughtful comments. The present study was financially supported by Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Grant 20002001 (to T. Matsuzawa); by Global Centers of Excellence (GCOE) Grants A06 and D07 (to Kyoto University); and by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grants 18-3451, 21-9340, and 22800034 (to S.Y.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1108517109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.de Waal FBM. Good Natured. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dugatkin LA. Cooperation Among Animals: An Evolutionary Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kappeler PM, van Schaik CP. Cooperation in Primates and Humans: Mechanisms and Evolution. Springer, London; New York: Berlin; Heidelberg; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauser MD, Chen MK, Chen F, Chuang E. Give unto others: Genetically unrelated cotton-top tamarin monkeys preferentially give food to those who altruistically give food back. Proc Biol Sci. 2003;270:2363–2370. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Waal FBM, Leimgruber K, Greenberg AR. Giving is self-rewarding for monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13685–13689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807060105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakshminarayanan VR, Santos LR. Capuchin monkeys are sensitive to others’ welfare. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R999–R1000. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takimoto A, Kuroshima H, Fujita K. Capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) are sensitive to others’ reward: An experimental analysis of food-choice for conspecifics. Anim Cogn. 2010;13:249–261. doi: 10.1007/s10071-009-0262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burkart JM, Fehr E, Efferson C, van Schaik CP. Other-regarding preferences in a non-human primate: Common marmosets provision food altruistically. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19762–19766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710310104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hare B, Kwetuenda S. Bonobos voluntarily share their own food with others. Curr Biol. 2010;20(5):R230–R231. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warneken F, Tomasello M. Altruistic helping in human infants and young chimpanzees. Science. 2006;311:1301–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1121448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warneken F, Hare B, Melis AP, Hanus D, Tomasello M. Spontaneous altruism by chimpanzees and young children. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamoto S, Humle T, Tanaka M. Chimpanzees help each other upon request. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melis A, et al. Chimpanzees help conspecifics obtain food and non-food items. Proc Biol Sci. 2011;278:1405–1413. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horner V, Carter JD, Suchak M, de Waal FBM. Spontaneous prosocial choice by chimpanzees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13847–13851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111088108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Waal FBM. Putting the altruism back into altruism: The evolution of empathy. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:279–300. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodall J. The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilby IC. Meat sharing among the Gombe chimpanzees: Harassment and reciprocal exchange. Anim Behav. 2006;71:953–963. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silk JB, et al. Chimpanzees are indifferent to the welfare of unrelated group members. Nature. 2005;437:1357–1359. doi: 10.1038/nature04243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen K, Hare B, Call J, Tomasello M. What's in it for me? Self-regard precludes altruism and spite in chimpanzees. Proc Biol Sci. 2006;273:1013–1021. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vonk J, et al. Chimpanzees do not take advantage of very low cost opportunities to deliver food to unrelated group members. Anim Behav. 2008;75:1757–1770. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamoto S, Tanaka M. The influence of kin relationship and a reciprocal context on chimpanzees’ (Pan troglodytes) sensitivity to a partner's payoff. Anim Behav. 2010;79:595–602. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamamoto S, Tanaka M. Selfish strategies develop in social problem situations in chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) mother-infant pairs. Anim Cogn. 2009;12(Suppl 1):S27–S36. doi: 10.1007/s10071-009-0276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ueno A, Matsuzawa T. Food transfer between chimpanzee mothers and their infants. Primates. 2004;45:231–239. doi: 10.1007/s10329-004-0085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamamoto S, Tanaka M. Do chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) spontaneously take turns in a reciprocal cooperation task? J Comp Psychol. 2009;123:242–249. doi: 10.1037/a0015838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brosnan SF, et al. Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) do not develop contingent reciprocity in an experimental task. Anim Cogn. 2009;12:587–597. doi: 10.1007/s10071-009-0218-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto S, Tanaka M. How did altruistic cooperation evolve in humans? Perspectives from experiments on chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Interact Stud. 2009;10(2):150–182. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Call J, Tomasello M. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? 30 years later. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savage-Rumbaugh S, Rumbaugh D, Boysen S. Linguistically mediated tool use and exchange by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Behav Brain Sci. 1978;4:539–554. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epstein R, Lanza RP, Skinner BF. Sympolic communication between two pigeons (Columba livia domestica) Science. 1980;207:543–545. doi: 10.1126/science.207.4430.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Svetlova M, Nichols SR, Brownell CA. Toddlers’ prosocial behavior: From instrumental to empathic to altruistic helping. Child Dev. 2010;81:1814–1827. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hare B, Melis AP, Woods V, Hastings S, Wrangham R. Tolerance allows bonobos to outperform chimpanzees on a cooperative task. Curr Biol. 2007;17(7):619–623. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Animal Care Committee . Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Primates. 2nd ed. 2002. (Primate Research Institute of Kyoto University, Kyoto) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.