Abstract

Ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) small subunit (RBCS) is encoded by a nuclear RBCS multigene family in many plant species. The contribution of the RBCS multigenes to accumulation of Rubisco holoenzyme and photosynthetic characteristics remains unclear. T-DNA insertion mutants of RBCS1A (rbcs1a-1) and RBCS3B (rbcs3b-1) were isolated among the four Arabidopsis RBCS genes, and a double mutant (rbcs1a3b-1) was generated. RBCS1A mRNA was not detected in rbcs1a-1 and rbcs1a3b-1, while the RBCS3B mRNA level was suppressed to ∼20% of the wild-type level in rbcs3b-1 and rbcs1a3b-1 leaves. As a result, total RBCS mRNA levels declined to 52, 79, and 23% of the wild-type level in rbcs1a-1, rbcs3b-1, and rbcs1a3b-1, respectively. Rubisco contents showed declines similar to total RBCS mRNA levels, and the ratio of Rubisco-nitrogen to total nitrogen was 62, 78, and 40% of the wild-type level in rbcs1a-1, rbcs3b-1, and rbcs1a3b-1, respectively. The effects of RBCS1A and RBCS3B mutations in rbcs1a3b-1 were clearly additive. The rates of CO2 assimilation at ambient CO2 of 40 Pa were reduced with decreased Rubisco contents in the respective mutant leaves. Although the RBCS composition in the Rubisco holoenzyme changed, the CO2 assimilation rates per unit of Rubisco content were the same irrespective of the genotype. These results clearly indicate that RBCS1A and RBCS3B contribute to accumulation of Rubisco in Arabidopsis leaves and that these genes work additively to yield sufficient Rubisco for photosynthetic capacity. It is also suggested that the RBCS composition in the Rubisco holoenzyme does not affect photosynthesis under the present ambient [CO2] conditions.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, RbcL, RBCS multigene family, Rubisco

Introduction

Ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco; EC 4.1.1.39) is a stromal protein which catalyses two competing reactions of photosynthetic CO2 fixation and photorespiratory carbon oxidation. The capacity of Rubisco is a rate-limiting factor for both reactions under conditions of saturating light at present atmospheric CO2 and O2 levels (Evans, 1986; Makino et al., 1988). Rubisco is the most abundant plant protein, accounting for 12–30% of total leaf nitrogen in C3 plants (Evans, 1989; Makino and Osmond, 1991; Makino et al., 2003). Stromal proteins are degraded during leaf senescence, and the resultant nitrogen is remobilized to growing organs and finally stored in seeds (Friedrich and Huffaker, 1980; Mae et al., 1983). Rubisco is a major source for recycling of nitrogen. Therefore, the amount of Rubisco in leaves is important for plant growth via both photosynthesis and nitrogen utilization.

In higher plants and green algae, Rubisco is composed of eight small subunits (RBCS) coded for by an RBCS multigene family in the nuclear genome, and eight large subunits (RbcL) coded for by a single RbcL gene in the plastome (Dean et al., 1989). The RBCS multigene family consists of 2–22 members, depending on the species (Sasanuma, 2001; Spreitzer, 2003). The number of expressing members and transcript abundance within the RBCS multigene family have been investigated in different tissues, under different environments, and/or during tissue development in some plant species including tomato (Wanner and Gruissem, 1991; Meier et al., 1995), Lemna gibba (Silverthorne and Tobin, 1990; Silverthorne et al., 1990), Arabidopsis (Dedonder et al., 1993; Cheng et al., 1998; Yoon et al., 2001), French bean (Knight and Jenkins, 1992; Sawbridge et al., 1996), maize (Ewing et al., 1998; Hahnen et al., 2003), wheat (Galili et al., 1998), rice (Suzuki et al., 2009b), and Eucalyptus (Suzuki et al., 2010). In rice, it has been demonstrated that four out of the five RBCS genes are highly expressed in leaf blades and that the total RBCS mRNA level is highly correlated with Rubisco content at their maxima irrespective of tissues and growth stages (Suzuki et al., 2009a, b). This suggests the possibility that the transcript level of total RBCS primarily determines the Rubisco content. In addition, a recent study has reported that individual suppression of the four major RBCS genes by RNA interference (RNAi) led to a decline in Rubisco content irrespective of growth stages, indicating that these four RBCS genes all contribute to accumulation of the Rubisco holoenzyme in leaf blades of rice (Ogawa et al., 2011). However, there has not been a clear correlation between total RBCS mRNA level and Rubisco content in RNAi-individual suppression lines of rice RBCS members (Ogawa et al., 2011).

To understand further the role of the RBCS multigene family in Rubisco synthesis, the relationship between total RBCS mRNA level and Rubisco content in Arabidopsis mutants of the RBCS multigene family was analysed. In Arabidopsis, four RBCS members, RBCS1A (At1g67090), RBCS1B (At5g38430), RBCS2B (At5g38420), and RBCS3B (At5g38410), have been identified (Krebbers et al., 1988). A screen was carried out for T-DNA insertion mutants of these RBCS genes, and mutant lines of RBCS1A and RBCS3B were isolated. The double mutant of these genes was generated. In these three mutants, the effects of RBCS mutations on the accumulation of mRNAs and protein of Rubisco, CO2 assimilation, and plant growth were examined.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The Columbia ecotype of Arabidopsis was used in all experiments. The T-DNA insertion lines GABI_608_F01 (rbcs1a-1) and SALK_117835 (rbcs3b-1) were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre and the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center. The double mutants of RBCS1A and RBCS3B (rbcs1a3b-1) were generated by sexual crosses. The homozygosities for the respective T-DNA insertions were confirmed by using PCR with gene-specific primers. Plants were grown hydroponically on horticultural rockwool as previously described (Wada et al., 2009) with slight modification. The photoperiod was 14 h light/10 h dark with fluorescent lamps (100 μmol quanta m−2 s−1) and the temperature was 23 °C day/18 °C night. The hydroponic solution contained 3 mM KNO3, 2.5 mM K-phosphate buffer (pH 5.5), 2.0 mM Ca(NO3)2, 2.0 mM MgSO4, 50 μM Fe-EDTA, 0.7 mM H3BO4, 170 μM MnCl2, 2.0 μM Na2MoO4, 100 μM NaCl, 5.0 μM CuSO4, 10 μM ZnSO4, and 0.1 μM CoCl2. The total volume of the supplied solution was 0.14 l per plant. Plants were firstly grown with a solution at a quarter concentration for healthy early growth. A quarter of the total volume was added to rockwool 1 week after sowing, and half of the total volume was added 2 weeks after sowing. The rosette leaves were numbered from the first emergent leaf except the cotyledon after germination. When the plants started bolting, rosette leaves were divided every two leaves from the first leaf, and leaves of the maximum leaf area were harvested, namely the fifth and sixth leaves in the wild type, rbcs1a-1, and rbcs3b-1, or the ninth and 10th leaves in rbcs1a3b-1, and used for RNA analysis and biochemical assays. The leaves were immediately frozen in liquid N2 and stored at –80 °C until analysis.

RNA analysis

Total RNA was isolated from leaves using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Isolated RNA was treated with DNase (DNA-free; Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) prior to reverse transcription with random hexamer primers (PrimeScript RT reagent kit; Takara, Ohtsu, Japan). In the reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis, an aliquot of the synthesized first-strand cDNA derived from 6.6 ng of total RNA was used for PCR amplification (total volume of 6 μl) with Taq polymerase (PrimeSTAR; Takara). The number of amplification cycles was 18 cycles for RBCS1A, 24 cycles for RBCS3B, and 17 cycles for 18S rRNA. The gene-specific primers for RT-PCR analysis were produced for amplifying the region including the open reading frame in each gene. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis, stained with SYBR Green I (Takara), and detected using a fluorescence image analyzer (LAS-4000 mini; Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan). 18S rRNA (QuantumRNA 18S internal standard; Ambion) was used as an internal standard. In quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis, an aliquot of the synthesized first-strand cDNA derived from 4.4 ng of total RNA was used for real-time PCR amplification (total volume of 20 μl) with StepOne and Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Calibration curves were made with standard plasmids for quantifications of the respective RBCS mRNA levels. Gene-specific primers for determination of RBCS mRNA levels were produced on the 3'-untranslated region (UTR) for the individual quantification of each gene. Sequences of primers used in both analyses are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1 available at JXB online.

Biochemical assays

Quantifications of chlorophyll, nitrogen, soluble protein, and Rubisco protein were performed as described previously (Izumi et al., 2010). Frozen rosette leaves were homogenized with an ice-chilled mortar and pestle in 50 mM Na-phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 2 mM iodoacetic acid, 0.8% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol, and 5% (v/v) glycerol. Chlorophyll was determined by the method of Arnon (1949). Soluble protein content was measured in the supernatant of part of the homogenate using a Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad, Philadelphia, PA, USA) with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard. Total leaf nitrogen was determined from part of the homogenate with Nessler’s reagent after Kjeldahl digestion. Triton X-100 (0.1%, final concentration) was added to the remaining homogenate. After centrifugation, the supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of SDS sample buffer containing 200 mM TRIS-HCl (pH 8.5), 2% (w/v) SDS, 0.7 M 2-mercaptoethanol, and 20% (v/v) glycerol, boiled for 3 min, and then subjected to SDS–PAGE. The Rubisco content was determined spectrophotometrically by formamide extraction of the Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250-stained bands corresponding to RBCS and RbcL of Rubisco separated by SDS–PAGE. Calibration curves were made with BSA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Soluble protein extracts were separated by SDS–PAGE, and immunoblotting was performed as described previously (Ishida et al., 2008), with anti-RBCS antibody (1:1000; Ishida et al., 1997). Signals were developed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and chemiluminescent reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and detected by LAS-4000 mini (Fujifilm). N-terminal amino acid sequencing was performed using a protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Soluble protein extracts were separated by SDS–PAGE and electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250-stained bands corresponding to RBCS proteins were applied to a protein sequencer.

Chlorophyll fluorescence measurement

The maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (PSII; Fv/Fm) was measured with a pulse-modulated fluorometer (Mini-PAM 101; Walz, Effeltrich, Germany). After 30 min dark incubation of each plant at room temperature (23–25 °C), F0 and subsequently Fm were measured with a measuring beam and a saturating pulse.

Gas-exchange measurement

The gas-exchange rate was measured on the eighth to 11th mature leaves at 5 d after bolting, the leaf area being sufficient for gas-exchange measurements, using the LI-6400 system (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA) in accordance with a previous report measuring photosynthesis in Arabidopsis leaves (Kebeish et al., 2007). Measurements were performed at a leaf temperature of 26 °C and a photon flux intensity of 800 μmol quanta m−2 s−1. The measurement was initiated at an ambient CO2 partial pressure (pCa) of 40 Pa to obtain the steady state of the gas-exchange rate, and the A versus intracellular CO2 partial pressure (pCi) was measured at pCa=10, 13, 16, 20, 40, 60, 100, 120, and 150 Pa. After measurements, fresh weight and leaf area were measured and the leaves were immediately frozen in liquid N2 and stored at –80 °C until the quantification of Rubisco content.

Statistical analysis

Tukey’s test was performed with JMP (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Isolation of Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutants of RBCS genes

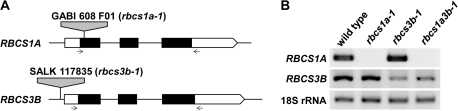

According to Krebbers et al. (1988) and The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) database (http://www.arabidopsis.org/), RBCS1A is located on chromosome 1, the other members being located in tandem on an 8 kb stretch of chromosome 5. The homology of the deduced amino acid sequences of the mature RBCS form is extremely high among the four RBCS genes (Krebbers et al., 1988; see Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online). The sequences of RBCS2B and RBCS3B are identical. The difference between RBCS1B, RBCS2B, and RBCS3B is only two residues. The difference between RBCS1A and the other RBCS proteins is 7–8 residues. T-DNA-inserted lines on the four RBCS members available at this time were obtained. The homozygous mutant lines of RBCS1A and RBCS3B were isolated by genomic PCR and they were designated as rbcs1a-1 and rbcs3b-1, respectively. The double mutant of both genes was generated by sexual crossing and designated as rbcs1a3b-1. The respective sites of the T-DNA insertions were confirmed by sequencing of genomic PCR products (Fig. 1A). The T-DNA insertion site in rbcs1a-1 was the coding region of the first exon, while the site in rbcs3b-1 was the promoter region before the 5′-UTR. To investigate the presence of RBCS1A and RBCS3B mRNAs in each mutant line, RT-PCR analysis was performed using gene-specific primers, which amplify regions including the open reading frame (Fig. 1B). RBCS1A mRNA was not detected in rbcs1a-1 and rbcs1a3b-1 plants. Although RBCS3B mRNA was detected in rbcs3b-1 and rbcs1a3b-1 plants, the levels were much lower than in wild-type plants. These results indicate that an RBCS1A knockout line and an RBCS3B knockdown line were isolated by screening from resource lines of Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutants and that a double mutant line of both genes was successfully generated.

Fig. 1.

Identification of rbcs1a-1, rbcs3b-1, and rbcs1a3b-1 mutants. (A) Genomic structures of RBCS1A and RBCS3B loci and T-DNA insertion sites. White and black boxes represent exons. The white boxes represent the untranslated regions and the black boxes represent the coding regions in exons. Grey boxes represent T-DNA. Arrows represent the positions of primer pairs used for RT-PCR analysis. (B) RT-PCR analysis for investigating RBCS1A and RBCS3B mRNA accumulation in leaves of rbcs mutants. Total RNA was isolated from leaves of wild-type, rbcs1a-1, rbcs3b-1, and rbcs1a3b-1 plants and subjected to RT-PCR analysis using gene-specific primers. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis, stained with SYBR Green I, and detected by a fluorescence image analyser. 18S rRNA was used as an internal control.

Phenotypes of isolated rbcs mutants

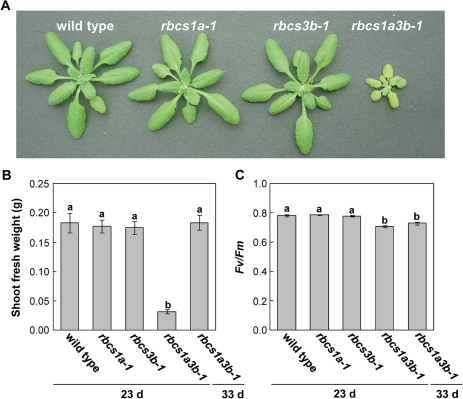

Wild-type and rbcs mutant plants were hydroponically grown on horticultural rockwool under long-day conditions. The growth rates of rbcs1a-1 and rbcs3b-1 mutants were the same as that of wild-type plants, while the growth of the rbcs1a3b-1 mutant was significantly delayed (Fig. 2A, B). Wild-type plants and the respective single rbcs mutants initiated bolting ∼23 d after sowing, whereas bolting was delayed to 33 d after sowing in rbcs1a3b-1 mutants. Despite the delay in the plant growth stage, the shoot fresh weight of rbcs1a3b-1 mutants became similar to those of wild-type plants and the other rbcs mutants at the initiation of bolting (Fig. 2B). The shoot of the rbcs1a3b-1 plant exhibited a pale green colour (Fig. 2A). The maximum quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm) in rbcs1a3b-1 leaves was found to be slightly lower than those in other genotypes, indicating slight damage to PSII function by photoinhibition (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Phenotypes of rbcs mutant plants under long-day growth conditions. (A) Photograph of wild-type, rbcs1a-1, rbcs3b-1, and rbcs1a3b-1 plants at 23 d after sowing. (B, C) Shoot fresh weight (B) and the maximum efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm) (C) of wild-type and each rbcs mutant when wild-type, rbcs1a-1, and rbcs3b-1 plants initiated bolting (23 d after sowing) or rbcs1a3b-1 plants initiated bolting (33 d after sowing). Data represent the means ±SE (n=4). Statistical analysis was performed by Tukey’s test; columns with the same letter were not significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

Effects of RBCS mutations on the transcript levels of the RBCS multigene family and RbcL

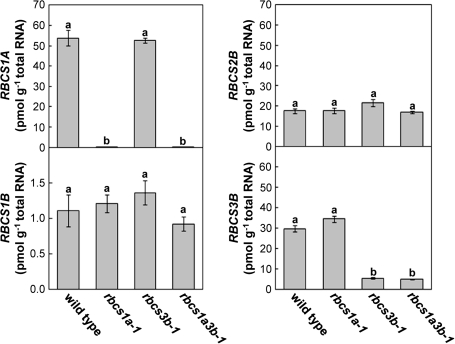

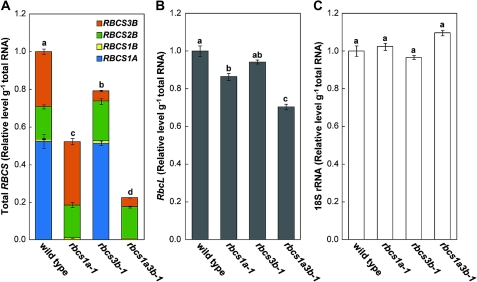

The transcript levels of individual RBCS genes were determined in leaves of wild-type and rbcs mutants at initiation of bolting (Figs 3, 4A). In wild-type plants, RBCS1A mRNA was the most abundant, and RBCS3B was the second. These two genes accounted for ∼80% of the total RBCS mRNA (Fig.4A). RBCS1A mRNA was not detected in the mutants with the T-DNA insertion in RBCS1A as found in the semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 3, see also Fig. 1B). In rbcs3b-1 and rbcs1a3b-1 mutants, the RBCS3B mRNA levels were suppressed to ∼20% of the wild-type level (Fig. 3). There were no significant differences in the mRNA accumulation of RBCS genes without the T-DNA insertion irrespective of genotype (Fig. 3). As a result, total RBCS mRNA levels significantly decreased to 52% of the wild-type level in rbcs1a-1 leaves, 79% in rbcs3b-1, and 23% in rbcs1a3b-1 (Fig. 4A). Although the mRNA levels of RbcL also decreased in the respective rbcs mutants in a manner similar to total RBCS mRNA, the extent was obviously lower: 86% of the wild-type level in rbcs1a-1 leaves, 94% in rbcs3b-1, and 70% in rbcs1a3b-1 (Fig. 4B). The level of DNA fragments derived from 18S rRNA was measured as an internal standard for mRNA analysis (Fig. 4C). This rRNA level did not differ among wild-type and rbcs mutant plants, indicating the validity of the method employed.

Fig. 3.

Transcript abundances of each member within the RBCS multigene family in leaves of rbcs mutants. Total RNA was isolated from leaves of wild-type, rbcs1a-1, rbcs3b-1, and rbcs1a3b-1 plants when each plant initiated bolting, and subjected to quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis using gene-specific primers for determination of transcript abundances of RBCS1A, RBCS1B, RBCS2B, and RBCS3B. Data represent the means ±SE (n=4). Statistical analysis was performed by Tukey’s test; columns with the same letter were not significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Effects of RBCS mutations on the transcript abundances of total RBCS and RbcL. Total RNA was isolated from leaves of wild-type, rbcs1a-1, rbcs3b-1, and rbcs1a3b-1 plants when each plant initiated bolting, and subjected to quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis using gene-specific primers for determination of transcript abundances of RBCS (A) and RbcL (B). The amount of total RBCS mRNA is a combination of the RBCS members shown in Fig. 3. All mRNA levels are shown as relative levels of the wild-type level. 18S rRNA was used as an internal control (C). Data represent the means ±SE (n=4). Statistical analysis was performed by Tukey’s test; columns with the same letter were not significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

Effects of RBCS mutations on leaf Rubisco content

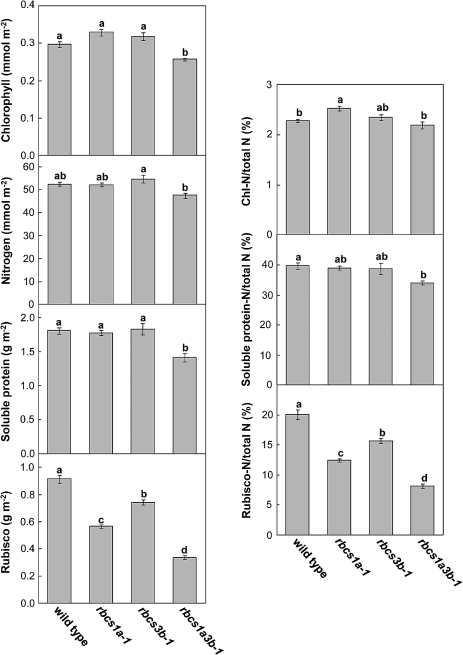

To investigate the effects of RBCS mutations on Rubisco content and nitrogen utilization in leaves, chlorophyll, nitrogen, soluble protein, and Rubisco protein were determined in mature leaves at initiation of bolting (Fig. 5). Chlorophyll and soluble protein contents per unit leaf area significantly decreased only in rbcs1a3b-1 plants. Leaf nitrogen content slightly decreased in rbcs1a3b-1 plants, the level being 90% of the wild-type level. On the other hand, the Rubisco content significantly declined in all rbcs mutants. The amount was ∼62% of the wild-type level in rbcs1a-1 leaves, 81% in rbcs3b-1, and 37% in rbcs1a3b-1. Therefore, the ratio of Rubisco-nitrogen (Rubisco-N) to total nitrogen also decreased to 62% of the wild-type level in rbcs1a-1, 78% in rbcs3b-1, and 40% in rbcs1a3b-1. The decreased amount of Rubisco-N in rbcs1a3b-1 was approximately equivalent to the sum of that in rbcs1a-1 and rbcs3b-1. Nitrogen partitioning to chlorophyll (Chl-N) was slightly increased only in rbcs1a-1 leaves; however, the increased amount was relatively small in relation to total leaf nitrogen. In spite of significant decreases of Rubisco-N, which accounted for 50% of the total soluble protein in wild-type leaves, the ratio of soluble protein-nitrogen (soluble protein-N) to total nitrogen did not change in rbcs1a-1 and rbcs3b-1 leaves. The soluble protein-N in rbcs1a3b-1 leaves decreased to 86% of the wild-type level; however, the extent was lower in comparison with the decline of Rubisco-N (i.e. 40% of the wild-type level). These findings indicate that nitrogen for decreased Rubisco was predominantly partitioned to other soluble proteins in the respective rbcs mutants.

Fig. 5.

Effects of RBCS mutations on leaf Rubisco content. The amounts of chlorophyll, soluble protein, nitrogen, and Rubisco were determined in leaves of wild-type, rbcs1a-1, rbcs3b-1, and rbcs1a3b-1 plants when each plant initiated bolting. The ratios of chlorophyll-nitrogen (Chl-N/total N), soluble protein-nitrogen (Soluble protein-N/total N), and Rubisco-nitrogen (Rubisco-N/total N) to total nitrogen were calculated. Data represent the means ±SE (n=4). Statistical analysis was performed by Tukey’s test; columns with the same letter were not significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

Changes of the RBCS compositions in Rubisco holoenzyme

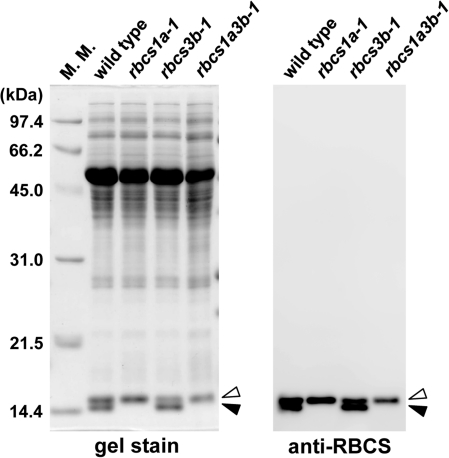

Two RBCS proteins with different molecular weights (14.7 kDa and 14.8 kDa expected values, respectively) were separated by SDS–PAGE (Fig. 6; Getzoff et al., 1998) and their N-terminal amino acid sequences were analysed. The N-terminal residue could not be identified (represented as X), as the methionine residue is post-translationally modified to N-methyl-methionine in some monocot and dicot plant species (Grimm et al., 1997). The N-terminal sequence of the larger RBCS was XKVWPP, identical to the sequence of RBCS1B, RBCS2B, and RBCS3B (see Supplementary Fig. S2 at JXB online). On the other hand, the N-terminal sequence of the smaller RBCS was XQVWPP, identical to that of RBCS1A (see Supplementary Fig. S2 at JXB online). These results indicate that the larger RBCS was derived from RBCS1B, RBCS2B, and RBCS3B genes, whereas the lower molecular weight RBCS was derived from RBCS1A. These proteins were designated as RBCSB and RBCSA proteins, respectively (white and black arrowheads in Fig. 6). In fact, RBCSA was not detected in leaves of rbcs1a-1 and rbcs1a3b-1 by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining and immunoblotting (Fig. 6). The ratio of RBCSB to RBCSA was decreased in rbcs3b-1 leaves (Fig. 6). These results indicate that the composition of RBCS in the Rubisco holoenzyme was altered in the respective rbcs mutants in comparison with that in wild-type plants.

Fig. 6.

SDS–PAGE analysis of Rubisco in leaves of rbcs mutants. Total soluble protein (10 μg for gel stain, 1 μg for immunoblotting) extracted from mature leaves of wild-type, rbcs1a-1, rbcs3b-1, and rbcs1a3b-1 plants was separated by SDS–PAGE, and either stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (gel stain) or detected by immunoblotting with anti-RBCS antibodies (anti-RBCS). White arrowheads indicate the RBCSB protein derived from RBCS1B, RBCS2B, and RBCS3B genes, and black arrowheads indicate the RBCSA protein derived from the RBCS1A gene. The sizes of molecular mass markers (M. M.) are indicated at the left of the stained gel.

Effects of RBCS mutations on photosynthesis

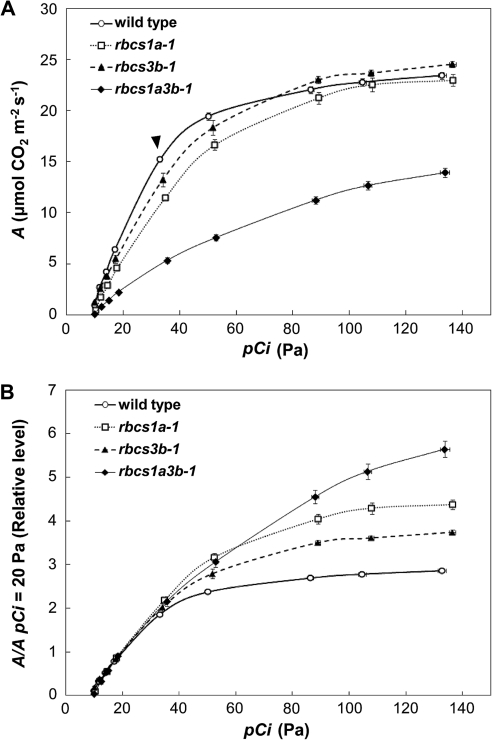

To examine the effects of RBCS mutations on photosynthetic capacity, the CO2 assimilation rate (A) was measured under light-saturated conditions in wild-type and rbcs mutants (Table 1). According to the C3 photosynthetic model of von Caemmerer and Farquhar (1981) and Sharkey (1985), A at low [CO2] is limited by Rubisco capacity, whereas A under high [CO2] conditions is limited by electron transport capacity or by the capacity of starch and sucrose synthesis to regenerate Pi for photophosphorylation. A at a pCa of 40 Pa was measured first (Table 1). A at a pCa of 40 Pa was reduced to 75% of the wild-type level in rbcs1a-1 leaves, 87% in rbcs3b-1, and 35% in rbcs1a3b-1, similar to the pattern of decreases of Rubisco content. There were no statistical differences in A per unit of Rubisco content. A similar trend was observed in A at a pCi of 20 Pa (Table 1). Therefore, it is indicated that declines in A below the present ambient [CO2] levels in the rbcs mutants are primarily accounted for by the declines in Rubisco content. It is also indicated that the changes in the composition of RBCS in the Rubisco holoenzyme did not greatly affect A under these [CO2] conditions. The pCi at a pCa of 40 Pa in the rbcs mutants tended to be slightly higher than in wild-type plants (Table 1). Figure 7A shows the [CO2] response of A in the respective genotypes. A under low [CO2] conditions was lower than that in wild-type plants in all the rbcs mutants (Fig. 7A). On the other hand, A above a pCi of 80 Pa, where A was [CO2] saturated, almost recovered to the wild-type level in rbcs1a-1 and rbcs3b-1 mutant plants, and the A in rbcs3b-1 tended to be slightly higher than that in wild-type plants (Fig. 7A). In rbcs1a3b-1 mutants, A was lower than in wild-type plants under all [CO2] conditions, and the [CO2] response of A was not saturated. To remove variation in leaf Rubisco contents from [CO2] responses of A of the respective rbcs mutants (Hudson et al., 1992), the ratios of A to A at a pCi of 20 Pa (A/A20) were calculated (Fig. 7B). Whereas A/A20 did not differ irrespective of the genotype below a pCa of 40 Pa, A/A20 under high [CO2] conditions in the rbcs mutants was higher than in wild-type plants in the order rbcs1a3b-1, rbcs1a-1, and rbcs3b-1. This phenomenon corresponds to the extent of reduction in Rubisco content (Table 1), indicating that as Rubisco contents decline with RBCS mutations, A is saturated at higher [CO2] conditions.

Table 1.

Effects of RBCS mutations on the rate of CO2 assimilation under light saturation

| Genotype | A pCa=40 Pa (μmol CO2 m−2 s−1) | Rubisco (g m−2) | A pCa=40 Pa/Rubisco (mol mol−1 s−1) | pCi (Pa) | A pCi=20 Pa (μmol CO2 m−2 s−1) | A pCi=20 Pa/Rubisco (mol mol−1 s−1) |

| Wild type | 15.2±0.2 a | 1.05±0.02 a | 7.90±0.25 a | 33.1±0.4 a | 8.18±0.15 a | 4.24±0.10 a |

| rbcs1a-1 | 11.5±0.2 c | 0.72±0.02 c | 8.70±0.26 a | 34.9±0.3 a,b | 5.25±0.16 c | 3.99±0.19 a |

| rbcs3b-1 | 13.2±0.7 b | 0.96±0.03 b | 7.65±0.54 a | 34.0±0.3 a | 6.55±0.34 b | 3.79±0.28 a |

| rbcs1a3b-1 | 5.3±0.3 d | 0.32±0.02 d | 9.25±0.54 a | 35.6±0.4 b | 2.47±0.14 d | 4.30±0.32 a |

The rate of CO2 assimilation (A), its ratio to Rubisco (A/Rubisco), and the intercellular CO2 partial pressure (pCi) were measured at present ambient CO2 conditions (pCa=40 Pa) under light saturation (800 μmol quanta m−2 s−1) in mature leaves of wild-type, rbcs1a-1, rbcs3b-1, and rbcs1a3b-1 plants at 5 d after bolting. A and A/Rubisco at pCi=20 Pa are also shown.

Data represent the means ±SE (n=6–8). Statistical analysis was performed by Tukey’s test; values with the same letter were not significantly different (P ≤ 0.05).

Fig. 7.

Effects of RBCS mutations on the rate of CO2 assimilation versus intercellular CO2 partial pressure under light saturation. (A) The rate of CO2 assimilation (A) and intercellular CO2 partial pressure (pCi) were measured under light saturation (800 μmol quanta m−2 s−1) in mature leaves of the wild type (circles), rbcs1a-1 (squares), rbcs3b-1 (triangles), and rbcs1a3b-1 (rhombuses) at 5 d after bolting. The arrowhead indicates the point obtained at the present ambient CO2 partial pressure (pCa=40 Pa). (B) The rates of CO2 assimilation are shown as relative levels of the rate at pCi=20 Pa. Data represent the means ±SE (n=6–8).

Discussion

The RBCS multigene family is necessary to accumulate abundant Rubisco protein in Arabidopsis

In the present study, it was found that T-DNA insertion into RBCS1A and RBCS3B in Arabidopsis led to a decline in Rubisco content. When these genes were simultaneously suppressed by sexual crossing, the decline in Rubisco content was similar to the sum of the contents in the respective mutants. These results clearly indicate that RBCS1A and RBCS3B contribute to the accumulation of the Rubisco holoenzyme in Arabidopsis leaves and that these genes work additively to yield Rubisco at the wild-type level. The decline in Rubisco content was dependent on that of the total RBCS mRNA level in the rbcs mutants (Figs 4, 5), suggesting that in Arabidopsis, the total RBCS mRNA level primarily determines the Rubisco content in mature leaves and that several RBCS genes serve to transcribe a high level of their mRNA for Rubisco synthesis. Rubisco capacity is inefficient as the CO2-fixing enzyme of photosynthesis because of its very slow catalytic rate, the low affinity for atmospheric CO2, and the use of O2 as an alternative substrate for the competing process of photorespiration (Farquhar et al., 1980). Therefore, while Rubisco is the most abundant plant protein, it is a rate-limiting factor of photosynthesis. It seems that several RBCS genes are necessary for accumulation of a high amount of Rubisco, as several RBCS genes are highly expressed in leaves of many other plant species (Silverthorne et al., 1990; Wanner and Gruissem, 1991; Knight and Jenkins, 1992; Meier et al., 1995; Ewing et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 2009b, 2010). The present study showed experimentally that several RBCS genes are necessary for highly abundant accumulation of Rubisco protein.

On the other hand, the changes in content or synthesis of the Rubisco holoenzyme do not always correspond to that of the total RBCS mRNA level in some cases. For example, the increase in Rubisco protein content was smaller than that in the total RBCS mRNA level when one of the RBCS genes was overexpressed in rice (Suzuki et al., 2007, 2009a). Additionally, changes in the mRNA levels and the rate of synthesis of Rubisco are not tightly correlated with each other during leaf senescence, especially after an increase in nitrogen supply to the plants (Imai et al., 2008). For an understanding of the regulation mechanism of Rubisco synthesis, it may be important to investigate the reason why changes in Rubisco content do not reflect those in total RBCS mRNA levels in certain cases.

Leaf Rubisco content is greatly changed during the leaf life span. In rice leaf blades, Rubisco synthesis is very active during leaf expansion and declines remarkably during senescence, with similar changes in the RBCS and RbcL mRNA levels, indicating that synthesized Rubisco content is primarily determined by the RBCS and RbcL mRNA levels during leaf expansion, whereas the major determinant of Rubisco content in senescent leaves is Rubisco degradation (Suzuki et al., 2001). The present preliminary analysis showed similar declines of total RBCS mRNA levels and Rubisco content in senescent leaves of Arabidopsis wild-type plants, suggesting that several RBCS genes are required for synthesis of highly abundant Rubisco during the young stage of Arabidopsis leaves. The age-dependent change of RBCS mRNA levels is an important aspect for the determination of Rubisco content, since leaf Rubisco contents actually depend on the balance of the synthesis and the degradation throughout the leaf life span.

In Arabidopsis leaves, it has been reported that the ratio of RBCS mRNA to total RBCS mRNA changed depending on the growth temperature (Yoon et al., 2001). As the growth temperature was raised, the RBCS1A mRNA level increased and the RBCS3B mRNA level declined, while the mRNA levels of RBCS1B and RBCS2B did not change drastically. It has also been reported that the Arabidopsis RBCS multigene family differentially responds to light (Dedonder et al., 1993). Therefore, the levels of contribution of the respective RBCS genes may vary depending on the growth conditions. Recently, a gene duplication event, where RBCS1B is lost and substituted by a duplicate of RBCS2B, has been found in eight of 100 Arabidopsis accessions (Schwarte and Tiedemann, 2011). It is of interest how changes in RBCS mRNA levels depending on environments or a substitution event affect the total RBCS mRNA level and Rubisco content in Arabidopsis leaves.

The interaction between RBCS and RbcL expression

The expression of RBCS in the nucleus and RbcL in the chloroplast must be tightly coordinated in Rubisco synthesis. A previous study has indicated in rice that the total RBCS mRNA level was highly positively correlated with the RbcL mRNA level irrespective of tissues and growth stages (Suzuki et al., 2009b). The decreased amount of RBCS and RbcL mRNA was approximately the same in RBCS-antisense rice or RNAi-individual suppression lines of rice RBCS members (Suzuki et al., 2009a, b; Ogawa et al., 2011). These results suggest that the transcription of RBCS and RbcL was regulated in a well-coordinated manner in rice. On the other hand, it has been demonstrated in tobacco plants that the suppression of RBCS mRNA causes the reduction of RbcL protein without any change in RbcL mRNA accumulation, suggesting that the expression of RbcL is regulated in response to that of RBCS at the translational and/or post-translational level (Rodermel et al., 1996; Wostrikoff and Stern, 2007; Ichikawa et al., 2008). In Arabidopsis rbcs mutants, the mRNA levels of RbcL declined in a manner positively correlated to those of total RBCS (Fig. 4A, B), indicating that gene expression of RBCS and RbcL is also regulated coordinately at the transcript level in Arabidopsis. However, the extent of the decrease of RbcL mRNA was obviously lower than that of total RBCS (Fig. 4A, B). Therefore, it is likely that RbcL gene expression is also regulated at the post-transcriptional and/or translational level in Arabidopsis. The difference between Arabidopsis, tobacco, and rice will provide important information on the regulation of RBCS and RbcL expression. In Chlamydomonas, expression of the chloroplast petA gene coding for cytochrome f, a major subunit of the cytochrome b6f complex, is controlled by nucleus-encoded factors, MCA1 and TCA1 (Loiselay et al., 2008). MCA1 is required for the stable accumulation and translational enhancement of the petA mRNA, whereas MCA1 is degraded upon interaction with unassembled cytochrome f (Boulouis et al., 2011). This control of petA expression is a well-studied example of the control by epistasy of synthesis (CES), which is a negative feedback mechanism down-regulating cytochrome f synthesis when its assembly within the cytochrome b6f complex is compromised. Rubisco RbcL is suggested to be a CES protein in tobacco plants (Wostrikoff and Stern, 2007). The CES mechanism regulating accumulation and translation of the RbcL mRNA via unassembled RbcL may function in chloroplasts of Arabidopsis rbcs mutants.

The involvement of the RBCS multigene family in the characteristics of leaf photosynthesis

The declines of CO2 assimilation rates in the rbcs mutants under conditions of saturating light and the present [CO2] levels were primarily accounted for by declines in Rubisco content (Table 1). This suggests that several Arabidopsis RBCS genes are employed to acquire sufficient photosynthetic capacity via high accumulation of the Rubisco holoenzyme. On the other hand, the changes in RBCS composition in the Rubisco holoenzyme did not greatly affect the photosynthetic characteristics, since A/Rubisco did not differ among the genotypes (Table 1). The catalytic site of Rubisco is located on RbcL, and RBCS does not have a catalytic site (Andersson, 1996); however, some reports have suggested that RBCS affects the catalytic performance of Rubisco. The CO2/O2 specificity of hybrid Rubisco holoenzymes with Chlamydomonas RbcL and plant RBCS, derived from spinach, Arabidopsis, or sunflower, was higher than that of Chlamydomonas Rubisco, but was not equal to that of the respective plant Rubiscos (Genkov et al., 2010). A recent study has reported that the introduction of RBCS derived from sorghum C4 Rubisco, which has a higher catalytic rate than rice Rubisco, enhances the Rubisco catalytic rate in transgenic rice (Ishikawa et al., 2011). There is a difference of eight amino acid residues between mature forms of RBCSA and RBCSB in Arabidopsis (see Supplementary Fig. S2 at JXB online). It is controversial whether there are some functional differences among members of the RBCS multigene family especially with respect to enzymatic properties such as the catalytic rate, CO2/O2 specificity, and stability (Spreitzer, 2003).

The rbcs mutants showed characteristics of photosynthesis and plant growth similar to those of previously reported RBCS-antisense tobacco and rice plants, such as declines in A at low [CO2] and an increase in pCi (Table 1; Hudson et al., 1992; Makino et al., 1997). When RBCS-antisense tobacco plants were grown under low irradiance, A as well as biomass production were not reduced until the Rubisco content became <50% of the wild-type level (Quick et al., 1991a, b). Slight photoinhibition was observed in the RBCS-antisense tobacco with a severe decline in Rubisco content (Quick et al., 1991b). These phenomena were also observed for Arabidopsis rbcs mutants (Figs 2, 5). In RBCS-antisense rice, nitrogen partitioning to other soluble proteins increased at the expense of that to Rubisco (Suzuki et al., 2009a). Similar results were obtained with the changes of nitrogen partitioning in the Arabidopsis rbcs mutants (Fig. 5). It has been reported that A is always limited by Rubisco capacity even under high [CO2] conditions in RBCS-antisense plants with severe reduction of Rubisco content (Hudson et al., 1992; Makino et al., 2000) such as rbcs1a3b-1 plants (Fig. 7). These common characteristics indicate that an impact of RBCS mutations on photosynthesis and plant growth in Arabidopsis is mainly caused by the decline in Rubisco content, and several RBCS genes contribute to normal plant growth via high accumulation of Rubisco. In RBCS-antisense rice plants with 65% of wild-type Rubisco content, photosynthetic recovery under high [CO2] conditions has been found, and nitrogen-use efficiency of photosynthesis was improved under saturating [CO2] and light conditions (Makino et al., 1997). A in the rbcs3b-1 mutants under high [CO2] conditions tended to be higher than in wild-type plants, although the difference was slight (Fig. 7A). It is of interest how the rbcs3b-1 mutants grow under high [CO2] and high light conditions.

Concluding remarks

In the present study, it is found that T-DNA mutations of RBCS1A and RBCS3B among four members of the Arabidopsis RBCS multigene family led to declines in the total RBCS mRNA level, Rubisco protein content, and A at present ambient [CO2] conditions. These findings indicate that RBCS1A and RBCS3B contribute to accumulation of Rubisco in Arabidopsis leaves and that these genes work additively to yield sufficient Rubisco for photosynthetic capacity.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Figure S1. Sequences of primers for the RBCS multigene family, RbcL, and 18S rRNA used in RT-PCR analysis.

Figure S2. Alignment of deduced amino acid sequences of the Arabidopsis RBCS multigene family.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Salk Institute Genomic Analysis Laboratory, GABI-Kat, the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC), and the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (NASC) for providing Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutants. We also thank Dr Wataru Yamori for technical advice on gas-exchange measurement. This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research no. 21-6184 to MI, Research Fellowships of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Yong Scientists to MI), by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (Scientific Research in a Proposed Research Area no. 21114006 to AM and no. 23119503 to HI), and by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan (Genomics for Agricultural Innovation GPN0007 to AM.

References

- Andersson I. Large structures at high resolution: the 1.6 angstrom crystal structure of spinach ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase complexed with 2-carboxyarabinitol bisphosphate. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1996;259:160–174. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnon DI. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts—polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiology. 1949;24:1–15. doi: 10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulouis A, Raynaud C, Bujaldon S, Aznar A, Wollman FA, Choquet Y. The nucleus-encoded trans-acting factor MCA1 plays a critical role in the regulation of cytochrome f synthesis in Chlamydomonas chloroplasts. The Plant Cell. 2011;23:333–349. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.078170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SH, Moore BD, Seemann JR. Effects of short- and long-term elevated CO2 on the expression of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase genes and carbohydrate accumulation in leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Plant Physiology. 1998;116:715–723. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.2.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean C, Pichersky E, Dunsmuir P. Structure, evolution, and regulation of rbcS genes in higher plants. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 1989;40:415–439. [Google Scholar]

- Dedonder A, Rethy R, Fredericq H, Vanmontagu M, Krebbers E. Arabidopsis rbcS genes are differentially regulated by light. Plant Physiology. 1993;101:801–808. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.3.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR. The relationship between carbon-dioxide-limited photosynthetic rate and ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate-carboxylase content in two nuclear–cytoplasm substitution lines of wheat, and the coordination of ribulose-bisphosphate-carboxylation and electron-transport capacities. Planta. 1986;167:351–358. doi: 10.1007/BF00391338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR. Photosynthesis and nitrogen relationships in leaves of C3 plants. Oecologia. 1989;78:9–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00377192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing RM, Jenkins GI, Langdale JA. Transcripts of maize RbcS genes accumulate differentially in C-3 and C-4 tissues. Plant Molecular Biology. 1998;36:593–599. doi: 10.1023/a:1005947306667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA. A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta. 1980;149:78–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00386231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich JW, Huffaker RC. Photosynthesis, leaf resistances, and ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase degradation in senescing barley leaves. Plant Physiology. 1980;65:1103–1107. doi: 10.1104/pp.65.6.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galili S, Avivi Y, Feldman M. Differential expression of three RbcS subfamilies in wheat. Plant Science. 1998;139:185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Genkov T, Meyer M, Griffiths H, Spreitzer RJ. Functional hybrid Rubisco enzymes with plant small subunits and algal large subunits: engineered rbcS cDNA for expression in Chlamydomonas. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285:19833–19841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.124230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getzoff TP, Zhu GH, Bohnert HJ, Jensen RG. Chimeric Arabidopsis thaliana ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase containing a pea small subunit protein is compromised in carbamylation. Plant Physiology. 1998;116:695–702. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.2.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm R, Grimm M, Eckerskorn C, Pohlmeyer K, Rohl T, Soll J. Postimport methylation of the small subunit of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase in chloroplasts. FEBS Letters. 1997;408:350–354. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahnen S, Joeris T, Kreuzaler F, Peterhansel C. Quantification of photosynthetic gene expression in maize C-3 and C-4 tissues by real-time PCR. Photosynthesis Research. 2003;75:183–192. doi: 10.1023/A:1022856715409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson GS, Evans JR, von Caemmerer S, Arvidsson YBC, Andrews TJ. Reduction of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase content by antisense RNA reduces photosynthesis in transgenic tobacco plants. Plant Physiology. 1992;98:294–302. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.1.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa K, Miyake C, Iwano M, Sekine M, Shinmyo A, Kato K. Ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit translation is regulated in a small subunit-independent manner in the expanded leaves of tobacco. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2008;49:214–225. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, Suzuki Y, Mae T, Makino A. Changes in the synthesis of Rubisco in rice leaves in relation to senescence and N influx. Annals of Botany. 2008;101:135–144. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida H, Nishimori Y, Sugisawa M, Makino A, Mae T. The large subunit of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase is fragmented into 37-kDa and 16-kDa polypeptides by active oxygen in the lysates of chloroplasts from primary leaves of wheat. Plant and Cell Physiology. 1997;38:471–479. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida H, Yoshimoto K, Izumi M, Reisen D, Yano Y, Makino A, Ohsumi Y, Hanson MR, Mae T. Mobilization of Rubisco and stroma-localized fluorescent proteins of chloroplasts to the vacuole by an ATG gene-dependent autophagic process. Plant Physiology. 2008;148:142–155. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.122770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa C, Hatanaka T, Misoo S, Miyake C, Fukayama H. Functional incorporation of sorghum small subunit increases the catalytic turnover rate of Rubisco in transgenic rice. Plant Physiology. 2011;156:1603–1611. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.177030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi M, Wada S, Makino A, Ishida H. The autophagic degradation of chloroplasts via Rubisco-containing bodies is specifically linked to leaf carbon status but not nitrogen status in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2010;154:1196–1209. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.158519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebeish R, Niessen M, Thiruveedhi K, Bari R, Hirsch HJ, Rosenkranz R, Stabler N, Schonfeld B, Kreuzaler F, Peterhansel C. Chloroplastic photorespiratory bypass increases photosynthesis and biomass production in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature Biotechnology. 2007;25:593–599. doi: 10.1038/nbt1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight MR, Jenkins GI. Genes encoding the small subunit of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase in Phaseolus vulgaris L.: nucleotide sequence of cDNA clones and initial studies of expression. Plant Molecular Biology. 1992;18:567–579. doi: 10.1007/BF00040672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebbers E, Seurinck J, Herdies L, Cashmore AR, Timko MP. Four genes in two diverged subfamilies encode the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase small subunit polypeptides of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Molecular Biology. 1988;11:745–759. doi: 10.1007/BF00019515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiselay C, Gumpel NJ, Girard-Bascou J, Watson AT, Purton S, Wollman FA, Choquet Y. Molecular identification and function of cis- and trans-acting determinants for petA transcript stability in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii chloroplasts. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2008;28:5529–5542. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02056-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mae T, Makino A, Ohira K. Changes in the amounts of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase synthesized and degraded during the life-span of rice leaf (Oryza sativa L.) Plant and Cell Physiology. 1983;24:1079–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Mae T, Ohira K. Differences between wheat and rice in the enzymic properties of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase and the relationship to photosynthetic gas exchange. Planta. 1988;174:30–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00394870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Nakano H, Mae T, Shimada T, Yamamoto N. Photosynthesis, plant growth and N allocation in transgenic rice plants with decreased Rubisco under CO2 enrichment. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2000;51:383–389. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.suppl_1.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Osmond B. Effects of nitrogen nutrition on nitrogen partitioning between chloroplasts and mitochondria in pea and wheat. Plant Physiology. 1991;96:355–362. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.2.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Sakuma H, Sudo E, Mae T. Differences between maize and rice in N-use efficiency for photosynthesis and protein allocation. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2003;44:952–956. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Shimada T, Takumi S, Kaneko K, Matsuoka M, Shimamoto K, Nakano H, Miyao-Tokutomi M, Mae T, Yamamoto N. Does decrease in ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase by antisense RbcS lead to a higher N-use efficiency of photosynthesis under conditions of saturating CO2 and light in rice plants? Plant Physiology. 1997;114:483–491. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.2.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier I, Callan KL, Fleming AJ, Gruissem W. Organ-specific differential regulation of a promoter subfamily for the ribulose-1,5-biphosphate carboxylase oxygenase small-subunit genes in tomato. Plant Physiology. 1995;107:1105–1118. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.4.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Suzuki Y, Yoshizawa R, Kanno K, Makino A. Effect of individual suppression of RBCS multigene family on Rubisco contents in rice leaves. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02434.x. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick WP, Schurr U, Fichtner K, Schulze ED, Rodermel SR, Bogorad L, Stitt M. The impact of decreased Rubisco on photosynthesis, growth, allocation and storage in tobacco plants which have been transformed with antisense rbcS. The Plant Journal. 1991a;1:51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Quick WP, Schurr U, Scheibe R, Schulze ED, Rodermel SR, Bogorad L, Stitt M. Decreased ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase in transgenic tobacco transformed with antisense rbcS. 1. Impact on photosynthesis in ambient growth conditions. Planta. 1991b;183:542–554. doi: 10.1007/BF00194276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodermel S, Haley J, Jiang CZ, Tsai CH, Bogorad L. A mechanism for intergenomic integration: abundance of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase small-subunit protein influences the translation of the large-subunit mRNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1996;93:3881–3885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasanuma T. Characterization of the rbcS multigene family in wheat: subfamily classification, determination of chromosomal location and evolutionary analysis. Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2001;265:161–171. doi: 10.1007/s004380000404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawbridge TI, Knight MR, Jenkins GI. Ontogenetic regulation and photoregulation of members of the Phaseolus vulgaris L. rbcS gene family. Planta. 1996;198:31–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00197583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarte S, Tiedemann R. A gene duplication/loss event in the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate-carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) small subunit gene family among accessions of Arabidopsis thaliana. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2011;28:1861–1876. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD. Photosynthesis in intact leaves of C3 plants—physics, physiology and rate limitations. Botanical Review. 1985;51:53–105. [Google Scholar]

- Silverthorne J, Tobin EM. Posttranscriptional regulation of organ-specific expression of individual rbcS mRNAs in Lemna gibba. The Plant Cell. 1990;2:1181–1190. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.12.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverthorne J, Wimpee CF, Yamada T, Rolfe SA, Tobin EM. Differential expression of individual genes encoding the small subunit of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase in Lemna gibba. Plant Molecular Biology. 1990;15:49–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00017723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer RJ. Role of the small subunit in ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2003;414:141–149. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Kihara-Doi T, Kawazu T, Miyake C, Makino A. Differences in Rubisco content and its synthesis in leaves at different positions in Eucalyptus globulus seedlings. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2010;33:1314–1323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Makino A, Mae T. Changes in the turnover of Rubisco and levels of mRNAs of rbcL and rbcS in rice leaves from emergence to senescence. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2001;24:1353–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Miyamoto T, Yoshizawa R, Mae T, Makino A. Rubisco content and photosynthesis of leaves at different positions in transgenic rice with an overexpression of RBCS. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2009a;32:417–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Nakabayashi K, Yoshizawa R, Mae T, Makino A. Differences in expression of the RBCS multigene family and Rubisco protein content in various rice plant tissues at different growth stages. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2009b;50:1851–1855. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Ohkubo M, Hatakeyama H, Ohashi K, Yoshizawa R, Kojima S, Hayakawa T, Yamaya T, Mae T, Makino A. Increased Rubisco content in transgenic rice transformed with the ‘sense’ rbcS gene. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2007;48:626–637. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD. Some relationships between the biochemistry of photosynthesis and the gas-exchange of leaves. Planta. 1981;153:376–387. doi: 10.1007/BF00384257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada S, Ishida H, Izumi M, Yoshimoto K, Ohsumi Y, Mae T, Makino A. Autophagy plays a role in chloroplast degradation during senescence in individually darkened leaves. Plant Physiology. 2009;149:885–893. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.130013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner LA, Gruissem W. Expression dynamics of the tomato rbcS gene family during development. The Plant Cell. 1991;3:1289–1303. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.12.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wostrikoff K, Stern D. Rubisco large-subunit translation is autoregulated in response to its assembly state in tobacco chloroplasts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2007;104:6466–6471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610586104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon M, Putterill JJ, Ross GS, Laing WA. Determination of the relative expression levels of Rubisco small subunit genes in Arabidopsis by rapid amplification of cDNA ends. Analytical Biochemistry. 2001;291:237–244. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.