Abstract

New molecular genetics approaches have been developed over the past several years to study brain serotonin (5-HT) neuron development and the roles of 5-HT neurons in behavior and physiology. These approaches were enabled by manipulation of the gene encoding the Pet-1 ETS transcription factor whose expression in the brain is restricted to developing and adult 5-HT neurons. Targeting of the Pet-1 gene led to the development of a mouse line with a severe and stable deficiency of embryonic 5-HT-synthesizing neurons. The Pet-1 transcription regulatory region has been used to create several new 5-HT neuron-type transgenic tools that have greatly increased the experimental accessibility of the small number of brain 5-HT neurons. Permanent and specific marking of 5-HT neurons with Pet-1-based transgenic tools have now been used for flow cytometry, whole cell electrophysiological recordings, progenitor fate mapping and live time lapse imaging of these neurons. Additional tools provide multiple strategies for conditional temporal targeting of gene expression in 5-HT neurons at different stages of life. Pet-1 based approaches have led to advances in understanding the role of 5-HT neurons in respiration, thermoregulation, emotional behaviors, maternal behavior, and the mechanism of antipsychotic drug actions. In addition, these approaches have begun to reveal the molecular basis of 5-HT neuron heterogeneity and the transcriptional mechanisms that direct 5-HT neuron-type identity, maturation and maintenance.

Brain serotonin (5-HT) neuron signaling is a well known form of neuromodulation that shapes many behaviors and physiological processes through interactions with at least fourteen broadly distributed postsynaptic receptor subtypes (Berger et al., 2009, Filip and Bader, 2009). The seemingly ubiquitous neuromodulatory role of the 5-HT system is effected by about 26,000 neurons in the rodent brain (Ishimura et al., 1988). These small numbers of neurons are sparsely intermingled with many non-serotonergic neurons in most of the raphe nuclei. In addition, while many 5-HT neurons are clustered in the midline raphe about 35% of them are scattered off the midline in disparate regions of the midbrain, pons and medulla (Steinbusch, 1981). Similar to most neuronal-types, this experimentally unwieldy neuroanatomical organization has made it very difficult to access 5-HT neurons for molecular and cellular studies of their development and their impact on postnatal behavior and physiology. Although genetic loss and gain of function studies have implicated the broadly expressed serotonin transporter gene (Sert) in numerous behavioral and physiological processes (Murphy et al., 2008), genetic-based methods to selectively and stably alter 5-HT neuron gene expression at different stages of life have been lacking. The identification of Pet-1 (Pheochromocytoma 12 ets) (Fyodorov et al., 1998), an ETS (E26-specific) transcription factor gene, provided a solution to this methodological shortcoming. This review describes how the unique expression pattern of Pet-1 has been exploited to create 5-HT neuron-type genetic based experimental approaches. The power of these approaches is then illustrated by highlighting some of their recent applications to questions that have been impossible or difficult to address with previously established experimental approaches: 1) transcriptional mechanisms that control 5-HT neuron identity, 2) the impact, in the intact animal, of 5-HT neuron perturbation at different stages of life on behavior, physiology, and pharmacology and 3) 5-HT neuron molecular heterogeneity.

Pet-1 encodes a class 1 ETS factor whose human orthologue is Fifth Ewing Variant (Fev), an ETS gene whose fusion to the EWS locus in a chromosomal translocation was identified in a subset of Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumors (Peter et al., 1997). A degenerate RT-PCR screen, aimed at identifying ETS factors expressed in the nervous system, led to the discovery of Pet-1 sequences in PC12 cell total RNA. RNase protections assays then revealed extremely weak expression of Pet-1 in total RNA isolated from whole brain. Consistent with the weak protection signal, a follow up in situ hybridization study indicated that Pet-1 transcripts were restricted to the raphe nuclei. In situ hybridization combined with anti-tryptophan hydroxylase (Tph) immunostaining showed that Pet-1 is expressed in what appeared to be all 5-HT-synthesizing neurons of the rodent brain (Hendricks et al., 1999). Expression of rat and mouse Pet-1 in the brain is induced specifically in postmitotic 5-HT neuron precursors about 0.5 days before the initiation of brain 5-HT synthesis (Hendricks et al., 1999, Pfaar et al., 2002) Thus, Pet-1 is induced and maintained specifically in this single neuronal type across the lifespan. Pet-1 is unique among the known factors that constitute the transcriptional network that specifies serotonergic phenotype as it is the only one expressed specifically in 5-HT neurons (Scott and Deneris, 2005). Significantly, the spatiotemporal pattern of expression of the zebrafish orthologue, zPet-1, in the zebrafish brain is similar as it is restricted to raphe 5-HT neurons and is induced about five hours before the onset of zTph2, the gene encoding the isoform of the rate-limiting enzyme responsible for zebrafish hindbrain 5-HT synthesis. Interestingly, zPet-1 is not expressed in other zebrafish 5-HT-synthesizing neurons present in the diencephalon of this species but not in that of rodents (Lillesaar et al., 2007, Lillesaar et al., 2009). In support of its functional orthology, Fev is expressed in the human and primate raphe in a pattern that suggests it is restricted to 5-HT neurons (Maurer et al., 2004, Iyo et al., 2005, Lima et al., 2009). A recent study (Kriegebaum et al., 2010) reported detection of Fev transcripts by RT-PCR in various dissected human forebrain regions. However, the cellular source of the RNA template in these seemingly weak amplifications was not identified. Pet-1 is also expressed in small number of peripheral cell types including the 5-HT synthesizing enterochromaffin cells of the intestine, adrenal medulla and pancreatic islets (Fyodorov et al., 1998, Ota, 2005, Wang et al., 2010)

Pet-1 based approaches

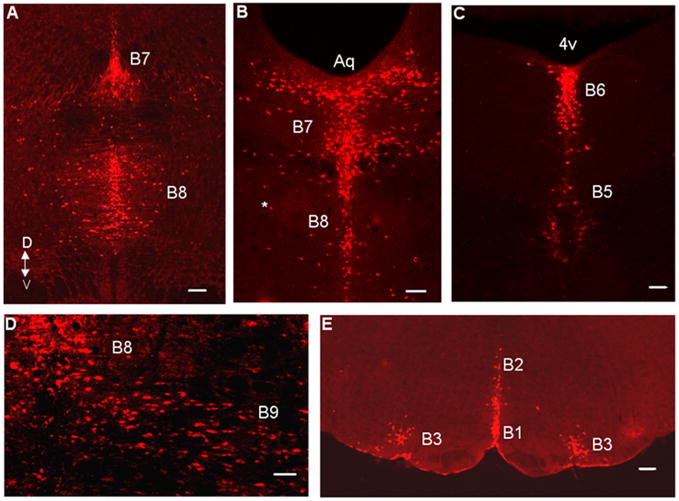

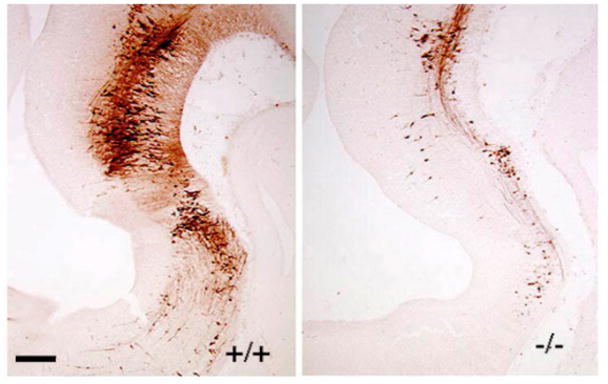

Manipulation of Pet-1 has enabled the development of diverse mouse molecular genetic tools for the study of 5-HT neurons (Table 1). The first approach, simple germline targeting of Pet-1, provided insight into the transcriptional induction of 5-HT neuron identity as acquisition of serotonergic phenotype failed to occur in most embryonic 5-HT neuron precursors in Pet-1−/− ventral hindbrain (Figure 1). Second, unlike 5-HT synthesis inhibitors and serotonergic neurotoxins whose effects may not be specific to 5-HT and whose physiological and behavioral effects may not depend on 5-HT depletion (Choi et al., 2004, Knuth and Etgen, 2004, Dailly et al., 2006), Pet-1 targeting resulted in the creation of a viable mouse strain in which the substantial deficiency of 5-HT-synthesizng neurons in Pet-1 mutant embryos is invariant across the lifespan. The Pet-1 mutant mouse, therefore, offered a new way with which to study the impact of an embryonic perturbation in serotonergic development on postnatal behavior and physiology. Third, the restricted expression of Pet-1 to 5-HT neurons in the brain suggested that the Pet-1 regulatory region could be used to create new genetic tools to specifically mark and manipulate the relatively small numbers of 5-HT neurons in the raphe as well laterally scattered ones (Figure 2). This idea led to the isolation of the mouse Pet-1 (Scott et al., 2005a) and human Fev (Krueger and Deneris, 2008) upstream enhancer regions (ePet, eFev). These enhancers were shown to direct highly reproducible transgene expression among independent transgenic lines in virtually all (>98%) 5-HT neurons in the developing and adult mouse brain with little or no ectopic expression, thus closely matching the spatiotemporal expression pattern of the endogenous Pet-1. A 40kb ePet mouse BAC fragment and a 60kb eFev human BAC fragment have been used to create several transgenes whose expression enabled permanent genetic marking of 5-HT neurons and constitutive and inducible control of gene expression specifically in these neurons (Scott et al., 2005b, Liu et al., 2010). In further support of the neuron-type specificity of Pet-1, a 5-HT neuron-specific enhancer region was isolated from the zebrafish zPet-1 upstream region. The zebrafish enhancer directs eGFP expression in all 5-HT neurons of the zebrafish raphe with faint ectopic expression in scattered cells of the forebrain (Lillesaar et al., 2009).

Table 1.

PeM-based Transgenic and Targeted Mice

| Name | Background | Description | Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pet-1−/− | C57BL/6*129sv; SJL congenic, N=10; C57BL/6J congenic, N=10 | Germ line targeted Pet-1 null | 5-HT neuron differentiation | Hendricks et al., 2003; Erickson et al., 2007; Bonnin et al., 2011 |

| Pet-1 floxed allele | C57BL/6*129Sv | Cre recombinase conditional allele | Temporal conditional targeting of Pet-1 | Liu et al., 2010 |

| ePet-Cre | C57BL/6*SJL | Cre recombinase controlled by Pet-1 enhancer sequences | Gene targeting and optogenetic viral gene expression in 5-HT neurons | Scott et al., 2005; Hodges et al., 2008; Dai et al., 2008; Samaco et at., 2009; Liu et al., 2010; Depuy et al., 2011 |

| ePet-1::Flpe | unknown | Flp recombinase controlled by Pet-1 enhancer sequences | Intersectional/subtractive fate mapping of 5-HT neurons | Jensen et at., 2008 |

| ePet::CreERT2ascend | C57BL/6*129 | Tamoxifen inducible Cre recombinase controlled by Pet-1 enhancer sequences | Temporal control of gene expression in ascending 5-HT neurons | Liu et al., 2010 |

| Pet1-CreERT2 | unknown | Tamoxifen inducible Cre recombinase controlled by Pet-1 enhancer sequences | Temporal control of gene expression in adult 5-HT neurons | Song et al., 2011 |

| eFev::LacZ (Fev60Z) | C57BL/6*129Sv | LacZ controlled by human Fev enhancer sequences | 5-HT neuron marker | Krueger and Deneris, 2008 |

| ePet-EYFP | C57BL/6*SJL | Enhanced yellow fluorescent protein controlled by Pet-1 enhancer sequences | 5-HT neuron flow cytometry. electophysiology, cell culture, live cell imaging | Scott et al., 2005; Wylie et al., 2010; Hawthorne et al., 2010; Hawthorne et al., 2011 |

| ePet::mycPet-1 | C57BL/6*129sv | Myc epitope-tagged Pet-1 cDNA controlled by Pet-1 enhancer sequences | Chromatin immunoprecipitation | Liu et al., 2010 |

| Pet1-tTS | 129S6Sv*C57BL/6*CBA | Tetracycline-dependent transcriptional suppressor controlled by Pet-1 enhancer sequences | Inducible suppression of Htr1A autoreceptor | Richardson-Jones et al., 2010; Richardson-Jones et at., 2011 |

Figure 1.

Anti-5-HT immunoreactivity in the wild type (left) and Pet-1−/− (right) anterior hindbrain at E11.5. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Figure 2.

A 40 kilobase mouse Pet-1 upstream genomic fragment directs LacZ transgene expression to virtually all 5HT neurons in the adult midbrain, pons and medulla. Scale bars: A, E, 200 μm; B–D, 100 μm. B1, raphe pallidus; B2, raphe obscurus; B3, ventrolateral medulla; B5, pontine median raphe; B6, pontine dorsal raphe; B7, midbrain dorsal raphe; B8, midbrain median raphe.

Transcriptional control of 5-HT neurons across the lifespan

Because Pet-1 expression in the brain is restricted to 5-HT neurons and precedes the onset of Tph2 expression and 5-HT synthesis it is the earliest specific marker of the serotonergic lineage. This expression characteristic has aided studies of the transcriptional determinants that specify serotonergic progenitors (Pattyn et al., 2003, Jacob et al., 2007) and suggested that Pet-1 regulatory elements could be used to mark early postmitotic serotonergic precursors to study their early development. In fact, expression of an ePet::EYFP transgene specifically marks virtually all serotonergic precursors during the earliest periods of their migration (Hawthorne et al., 2010). These Yfp+ cells have a bipolar and radially-shaped morphology; they express several markers of neuronal phenotype but not radial glia or markers of cellular proliferation. Consistent with their morphology and gene expression characteristics, time-lapse imaging of live Yfp+ precursors in slice cultures showed that 5-HT neurons migrate via somal translocation rather than by the more commonly studied radial glia-guided locomotion (Hawthorne et al., 2010).

Before the discovery of Pet-1 expression in 5-HT neurons very little was known about the intrinsic mechanisms that direct the development of these cells and how those mechanisms impact postnatal behavior and physiology (Rubenstein, 1998). Initial studies of Pet-1 function focused on determining its role in the transcriptional network that specifies serotonergic identity. Germline targeting of the Pet-1 locus created a null mutant in which no Pet-1 RNA expression could be detected in the brain. Consistent with its induction at the postmitotic precursor stage, normal numbers of serotonergic precursors were detected in Pet-1−/− brain. However, about 70% of these precursors failed to induce the serotonergic-type gene battery, Tph2, AADC, Sert, Vmat2, MaoB encoding 5-HT synthesis, reuptake, vesicular storage, and enzymatic degradation. The aborted development of 5-HT neurons in Pet-1−/− mice caused an 80–90% deficiency of adult 5-HT levels in brain and spinal cord (5-HT levels are normal in adult Pet-1+/− brain). However, this gene defect did not trigger the apoptotic elimination of these mutant cells at least in the dorsal raphe (Krueger and Deneris, 2008). Although the deficiency of 5-HT+ neurons in the Pet-1−/− brain is largely uniform across the nine raphe clusters in the midbrain, pons and medulla recent studies have shown that the 20–30% of Pet-1 resistant 5-HT neurons that remain in the Pet-1−/− brain comprise a functionally and morphologically distinct subset of 5-HT neurons that continue to innervate circuitry involved in autonomic and stress responses (Kiyasova et al., 2011). Loss of Pet-1 function does not affect the number of 5-HT producing enterochromaffin cells or the level of small intestinal mRNA encoding Tph1, the enzyme required for synthesis of peripheral 5-HT (Wang et al., 2010).

The ongoing expression of Pet-1 into adulthood raised the possibility that it continues to function after fulfilling its initial role in serotonergic neurogenesis. Thus, two Pet-1-based conditional targeting approaches were developed to determine whether Pet-1 regulates 5-HT system maturation during fetal life and maintenance of the serotonergic phenotype in adulthood. An ePet-Cre transgene that can direct recombination in 80–95% of 5-HT neurons, depending on the floxed target, was used to delete a floxed Pet-1 allele. Because Cre recombinase activity was not evident with the ePet-Cre transgene until 1–2 days after the completion of serotonergic neurogenesis, this genetic strategy was used to investigate requirements for Pet-1 during early 5-HT system maturation. Indeed, Pet-1 expression levels in Pet-1loxP/−; ePet-Cre (Pet-1eCKO) mice were normal at E11.5 when 5-HT neuron generation is largely complete but began to fade at E12.5 (Liu et al., 2010). A critical step in the maturation of 5-HT neuron function is the induction of the Htr1A and Htr1B autoreceptors that regulate 5-HT neuron firing frequency and transmitter release from the presynaptic terminal. Induction of these autoreceptor genes normally occurs at about E14 in the mouse (Liu et al., 2010). However, in Pet-1eCKO, Htr1A and Htr1B induction failed in the majority of 5-HT neurons. Moreover, in whole cell recordings of Pet-1 deficient 5-HT neurons that were genetically marked by ePet-Cre directed activation of the R26RYFP locus, 8-OH-DPAT, a 5-HT1A selective agonist, failed to elicit inwardly rectifying potassium currents that are characteristically elicited with the agonist in wildtype 5-HT neurons (Liu et al., 2010). These findings showed that induction of key autoreceptors during 5-HT system maturation depends on persistent Pet-1 expression. In addition to regulating the induction of autoreceptors during 5-HT system maturation, ongoing Pet-1 expression appears to be required to regulate innervation patterns of serotonergic axons (Liu et al., 2010). Injection of the retrograde tracer, Texas Red conjugated dextran, into the somatosensory cortex resulted in the marking of significantly fewer Pet-1 deficient cell bodies in the dorsal raphe (DRN) compared to the number of tracer-positive 5-HT neurons in littermate control DRN.

A tamoxifen-inducible Pet-1 based targeting approach was then developed to investigate further functions of Pet-1 specifically in adult 5-HT neurons (Liu et al., 2010). An ePet-CreERT2 transgenic line was established that expresses CreERT2 in nearly all 5-HT neurons of the midbrain, pons and medulla. Tamoxifen inducible targeting of LacZ expression in ROSAR26ePet-CreERT2 mice was detected specifically in 5-HT neurons and not in other regions of the brain. However, tamoxifen-inducible recombination directed by this line was largely restricted to the dorsal raphe, median raphe, and B9 cluster. Tamoxifen treatment of Pet-1loxP/−;ePet-CreERT2 (Pet-1aCKO) led to the targeting of Pet-1 in about 75% of 5-HT neurons in the adult ascending 5-HT system comprising the DRN, median raphe and B9 groups of 5-HT neurons; for reasons that are not yet clear Pet-1 expression in the descending 5-HT subsystem was not significantly altered with this approach. The loss of Pet-1 in the adult ascending system of Pet-1aCKO mice caused substantial decreases in the expression of Tph2 and Sert demonstrating that Pet-1 dependent transcription is required to regulate these two critical serotonergic genes across the lifespan. However, other genes such as AADC and Vmat2, whose embryonic induction depends on Pet-1 were not affected by loss of Pet-1 in adult 5-HT neurons. In addition to Tph2 and Sert, loss of adult Pet-1 resulted in a delayed loss of the vesicular glutamate transporter 3 (VGlut3) expression in the DRN. A subset of 5-HT neurons in the DRN normally express vGlut3, which may be required for glutamatergic/serotonergic co-transmission in these cells (Varga et al., 2009), and therefore this finding raises the intriguing possibility that Pet-1 may also be required for glutamatergic functions in 5-HT neurons. However, because Vglut3 is not restricted to 5-HT neurons additional histological studies will be required to determine whether Pet-1 is an intrinsic regulator of Vglut3 in 5-HT neurons.

Pet-1 based approaches have also been important for understanding the role of the LIM homeodomain protein, Lmx1b, in 5-HT neuron development. Nearly all ventral hindbrain precursors fail to acquire a serotonergic identity in germline-targeted Lmx1b mutant embryos demonstrating an essential role for Lmx1b in 5-HT neuron differentiation (Ding et al., 2003). However, Lmx1b null mutation is perinatal lethal (Chen et al., 1998) which precluded further studies of the Lmx1b deficiency in the postnatal period. To circumvent the lethality caused by global Lmx1b deficiency an Lmx1b floxed allele was crossed to ePet-Cre mice in order to generate conditionally targeted Lmx1b mice (Lmx1bf/f/p). Lmx1b expression was preserved during the period of serotonergic neurogenesis but began to decline at E12.5 in Lmx1bf/f/p mice. The conditional loss of Lmx1b resulted in a failure to maintain Tph2, Sert and Pet-1 expression. Interestingly, nearly all 5-HT neuron cell bodies were eliminated in the early postnatal brain resulting in >99% loss of 5-HT, while peripheral 5-HT levels were unaltered. Thus, serotonergic conditional targeting of Lmx1b revealed a critical role for this factor in the maintenance and survival of 5-HT neurons (Zhao et al., 2006). Despite the profound deficit in brain 5-HT the majority of Lmx1bf/f/p mice survive into adulthood and therefore this Pet-1-based conditionally targeted strain has been used in numerous studies aimed at determining the impact of a virtually complete serotonergic deficiency on behavior and physiology (see below).

Song et al. used a different Pet-1 BAC to express CreERT2 for inducible targeting of Lmx1b in adult 5-HT neurons. This Pet-1-CreERT2 BAC transgene directed recombination in 85% of 5-HT neurons but recombination was not detected elsewhere in the brain. Targeting of Lmx1b in adult 5-HT neurons revealed that similar to Pet-1, Lmx1b is also required to maintain Tph2 and Sert expression but not AADC expression in adult 5-HT neurons (Song et al., 2011). However, in contrast to Pet-1, Lmx1b was also required to maintain Vmat2 expression. Furthermore, unlike at embryonic stages Lmx1b was no longer required to maintain Pet-1 expression in adult 5-HT neurons. Although Lmx1b is required for the maintenance of midbrain dopaminergic (DA) neurons this targeting strategy had no effect on DA (and noradrenergic) phenotype, which further corroborates the 5-HT neuron-type specificity of the Pet-1 based targeting approaches.

Perturbation of 5-HT system development and its impact on physiology and behavior

Neonatal growth and survival

Because of their stable deficiencies of 5-HT synthesizing neurons, Pet-1−/− and Lmx1bf/f/p mice have been used extensively to determine the impact of embryonic disruption of serotonergic signaling on postnatal physiology and behavior in the absence of a maternal serotonergic defect. A highly anticipated experiment with Pet-1−/− mice was to determine whether embryonic disruption of 5-HT neurons would impair offspring viability. Although expected Mendelian proportions of viable Pet-1−/− births was found, 20–30% of the Pet-1−/− neonates did not survive to weaning, which was a significantly higher mortality compared to their +/+ and +/− littermates (Hendricks et al., 2003, Erickson et al., 2007). In addition, Pet-1−/− neonates had a significantly lower body weight at birth, which persisted into the second postnatal week but normalized in adulthood. Interestingly, Lmx1bf/f/p neonates were also found to have comparably impaired viability and growth trajectories with the later abnormality normalizing in young adulthood (Hodges et al., 2009). In support of a specific requirement for brain 5-HT synthesis, growth and viability was also found to be impaired, depending on the genetic background, in Tph2−/− neonates, which synthesize virtually no brain 5-HT but have normal peripheral (blood and gut) 5-HT levels (Alenina et al., 2009). Importantly, survival is normal in Tph1−/− mice that are diabetic and whose brain 5-HT levels are normal but peripheral 5-HT levels are < 10% wildtype levels (Walther et al., 2003a, Walther et al., 2003b). These findings support a model in which Pet-1/Lmx1b-transcriptional control of Tph2-dependent brain 5-HT synthesis but not peripheral 5-HT synthesis is required for normal neonatal growth trajectories and optimal viability.

Another experiment of particular interest was to test whether an embryonic deficiency of 5-HT neurons would lead to developmental abnormalities in brain cytoarchitecture. This question was stimulated by a large literature supporting a role for early 5-HT signaling in neural cell proliferation, differentiation, migration and circuit formation in the brain (Gaspar et al., 2003). However, in contrast to the overt disruption of forebrain circuitry in mice with genetically engineered increases in the levels of 5-HT (Cases, 1996), the substantial deficiency of 5-HT-synthesizing neurons in Pet-1−/− and the virtually complete absence in Lmx1bf/f/p mice did not cause gross structural alterations in CNS cellular organization (Hendricks et al., 2003, Zhao et al., 2006, Stankovski et al., 2007). Although subtle circuit alterations may yet be found these findings raise questions about the impact of brain 5-HT synthesis deficits on brain morphogenesis. It is important to keep in mind, however, that most 5-HT is synthesized outside the brain in multiple tissues and cell types. A widely discussed hypothesis posits that 5-HT produced in the periphery supplies the developing brain before blood-brain barrier formation and it is this source of 5-HT that is critically important for the fetal brain. Significantly, Bonnin et al., has shown that 5-HT levels are normal in the Pet-1−/− fetal forebrain until E16.5 despite the dramatic deficiency in hindbrain 5-HT synthesis beginning at E10.5. Further studies showed that 5-HT is synthesized in the placenta by the Tph1/AADC pathway and transported via the fetal circulation to the fetal forebrain before the arrival of 5-HT raphe axons (Bonnin et al., 2011). This provocative finding has stimulated great interest in determining the impact of placental 5-HT synthesis on early fetal brain development and postnatal behavior.

Maternal nurturing

Although correlative evidence in non-human primates suggested serotonergic function might be required for maternal behavior, a clear link was not established until the idea was tested in Pet-1−/− mice. When Pet-1−/− females were crossed to +/+ or Pet-1+/− males, normal numbers of offspring were born but all of them failed to survive within 4 days of birth regardless of their Pet-1 allelic genotype (Lerch-Haner et al., 2008). However, offspring mortality did not occur if the pups were cross-fostered to a wildtype mother at P0 or P1. Specific tests of maternal behavior showed significant deficits in pup retrieval and nest building and an absolute failure of the dams to huddle pups. These specific deficits were not accompanied by maternal olfactory deficits, changes in maternal anxiety-like behaviors or failure to nurse (Lerch-Haner et al., 2008). Further support for serotonergic function and specifically brain 5-HT synthesis but not peripheral 5-HT synthesis in maternal behavior was the finding that although normal numbers of offspring were born to Tph2−/− dams most of them died within 2–3 days of birth unless cross-fostered to +/+ dams (Alenina et al., 2009). Similar to Pet-1−/− dams, Tph2−/− dams delivered milk to their pups but exhibited deficits in pup retrieval and eventually abandoned them. In contrast to Pet-1−/− dams, however, Tph2−/− dams often cannibalized their pups but did not show deficits in nest construction. The different genetic backgrounds of the Pet-1−/− and Tph2−/− mice might be responsible for specific differences in nurturing abnormalities in these two targeted strains. Alternatively, the different types of 5-HT system lesions in these strains (complete loss of 5-HT synthesis in Tph2−/− mice versus preservation of some 5-HT neurons in Pet-1−/− mice) are a potential explanation for the phenotypic differences.

Respiration and thermoregulation

5-HT, substance P and TRH released from medullary 5-HT neurons are well-established modulators of CNS respiratory circuitry, in vitro, and the preponderance of evidence supports a model in which the overall effect of 5-HT neuron firing is to stimulate respiratory drive (Hodges and Richerson, 2008). What has been more difficult to address is the role 5-HT neurons play in breathing within the intact animal. Pet-1-based strategies have been used to investigate this question and are now preferred over older pharmacological and neurotoxin lesion approaches that have produced inconsistent effects on serotonergic depletion and contradictory effects on breathing (Hodges and Richerson, 2010). Plethysmographic recordings from Pet-1−/− newborns (Erickson et al., 2007) raised in pathogen free conditions showed that the embryonic deficiency of 5-HT-synthesizing neurons caused a delay in respiratory maturation as evidenced by an initially depressed breathing frequency and increased incidence of prolonged apneas. If Pet-1−/− neonates were raised under pathogen-exposed conditions, the variability of respiratory parameters significantly increased and the incidence of hypoxia-induced apneas increased dramatically in comparison to Pet-1−/− neonates raised in pathogen-free conditions (Erickson et al., 2007). These abnormalities largely resolved by the second postnatal week. In vitro studies identified depressed and unstable hypoglossal nerve discharges in medullary slices taken from Pet-1−/− neonates, suggesting altered serotonergic modulation or development of the central respiratory rhythm generator is responsible for the abnormal neonatal breathing behavior (Erickson et al., 2007). Both Pet-1−/− neonates (Erickson and Sposato, 2009) and adults (St-John et al., 2009) can generate normal gasps, however, Pet-1−/− neonates elicited an abnormal gasping pattern in response to hypoxia-induced apnea that delayed restoration of eupenic breathing via autoresuscitation (Erickson and Sposato, 2009). In addition, Pet-1−/− neonates display lowered resting heart rate and an increased magnitude and incidence of spontaneous bradycardias compared to littermate controls (Cummings et al., 2010).

Consistent with their larger, nearly total absence, of brain 5-HT synthesizing neurons compared to Pet-1−/− mice, Lmx1bf/f/p neonates have more dramatic breathing abnormalities including severe hypoventilation and more frequent and longer apneas (Hodges et al., 2009). Similar to Pet-1−/− neonates these abnormalities largely resolved, albeit more slowly, as the animal matured. Furthermore, Pet-1−/− adult females but not males exhibit deficits in resting breathing but these deficits were modest compared to those in female and male Lmx1bf/f/p mice (Hodges et al., 2011).

An optogenetic study of 5-HT neurons in the raphe obscurus (ROb) was aimed at determining what effect stimulation of these cells has on respiration, in vivo (Depuy et al., 2011). An adeno-associated viral construct was injected into the ROb for conditional expression of inverse orientated double-floxed channelrhodopsin-mCherry sequences in ePet-Cre mice. Co-immunostaining indicated that 97% of infected cells could be identified as Tph+ 5-HT neurons and nearly all of these cells were within the limits of ROb. mCherry+ serotonergic axonal projections were identified in close association with all of the respiratory motor neuron groups in the medulla and the pre-Botzinger complex, the putative site of the respiratory rhythm generator. Photostimulation of the ChR2+ 5-HT neurons in the ROb caused increased breathing frequency and magnitude, which were attenuated by the serotonergic receptor antagonist, methysergide. These findings nicely demonstrate the power of 5-HT neuron specific optogenetic approaches, in vivo, for understanding the physiological roles of specific subsets of 5-HT neurons.

Pet-1 and Lmx1bf/f/p mice have also been used to clarify the role of the 5-HT system in thermoregulation, in vivo. Although adult Lmx1bf/f/p mice maintain normal circadian control of core body temperature under ambient conditions, they have a severe defect in maintaining core body temperature in response to moderate cold challenge. This defect is the result of abnormal shivering responses and sustained activation of brown adipose tissue and not from a defect in thermosensory perception (Hodges et al., 2008). Both female and male Pet-1−/− mice show a defect in defense to cold challenge but it is less severe than that seen in Lmx1bf/f/p mice (Hodges et al., 2011).

Aggression, fear, and anxiety-related behaviors

A rich history of studies in humans, non-human primates and rodents has demonstrated that alterations in 5-HT system function can have dramatic effects on stress and emotion-related behaviors (Holmes, 2008). For example, pharmacological blockade of Sert (Ansorge et al., 2008, Popa et al., 2008) or gene targeted loss of Sert function in mice causes highly reproducible alterations in anxiety-like and depressive-like behaviors (Murphy and Lesch, 2008). Non-conditional targeting of Htr1A (Heisler et al., 1998, Parks et al., 1998, Ramboz et al., 1998) and pharmacological blockade of 5-HT1A receptors in the early postnatal period also results in increased anxiety-like behavior (Lo Iacono and Gross, 2008). In addition, Tph2 loss of function has been reported to result in increased aggression (Beaulieu et al., 2008, Alenina et al., 2009) and anxiety-like behavior (Beaulieu et al., 2008) although other studies of Tph2 deficient mice have reported more mild behavioral alterations (Savelieva et al., 2008). Because of Pet-1’s role in the induction of Tph2, Sert, and Htr1A a logical question was whether disruption of Pet-1-dependent transcription would also alter these behaviors. Consistent with many of the Tph2−/− and Sert−/− studies, behavioral analyses of Pet-1−/− mice reported significantly increased male aggression in the resident-intruder assay (Hendricks et al., 2003). Further evidence in support of serotonergic transcriptional control of aggression was the finding of increased male aggression in ePet-Cre direct loss of a floxed allele encoding the transcriptional repressor, methyl CpG binding protein (MeCP2), in 5-HT neurons (Samaco et al., 2009).

Pet-1−/− mice also showed striking increases in anxiety-like behavior in the elevated plus maze and open field versus +/+ littermate controls (Hendricks et al., 2003). A recent study used another ePet controlled transgene, Pet1-tTS, for 5-HT neuron-specific expression of a tetracycline-regulated transcriptional suppressor, tTS (Richardson-Jones et al., 2010). This transgene was used to specifically diminish Htr1A autoreceptor expression (but not Htr1A postsynaptic heteroreceptors) from a knock-in allele in which tetracycline transactivator operator sequences were introduced into the Htr1A promoter region. Interestingly, suppression of Hrt1A autoreceptors beginning in the embryo and continuing into adulthood led to increased anxiety-like behaviors in the open field and light/dark choice exploration tests (Richardson-Jones et al., 2011). In contrast, reducing the expression of Htr1A autoreceptors in adult 5-HT neurons by removing doxycycline from chow fed to mice aged 7 weeks led to increased stress responses but not increased anxiety-like behavior in the conflict-based assays (Richardson-Jones et al., 2010). These findings support a model in which Pet-1-dependent induction of Htr1A autoreceptors and/or Sert and Tph2 during development is required for development of normal anxiety-like behaviors. However, other laboratories failed to detect increased anxiety-like behaviors in Pet-1−/− mice in conflict-based aversive environments perhaps because of differing testing conditions (Schaefer et al., 2009, Kiyasova et al., 2011). Instead, Pet-1−/− mice showed significantly increased contextual and acoustic cue conditioned fear responses (Kiyasova et al., 2011). Lmx1bf/f/p mice also showed enhanced contextual fear memory but reduced anxiety-like behavior (Dai et al., 2008). Thus, notwithstanding inconsistent findings, studies of Pet-1−/− and Lmx1bf/f/p mice indicate that altered transcriptional induction of 5-HT neuron identity leads to susceptibility for altered emotional behaviors in adulthood.

To determine whether Pet-1-dependent transcription was required in adult 5-HT neurons to preserve normal anxiety-like behaviors, 6–8 week old tamoxifen-treated Pet-1aCKO mice were analyzed in the elevated plus maze, open field and light-dark box tests. Two different cohorts of tamoxifen-treated but not vehicle treated Pet-1aCKO mice tested during different seasons showed significantly elevated anxiety-like behavior in all three tests compared to tamoxifen-treated littermate Pet-1flox/− controls (Liu et al., 2010); tamoxifen treatment did not alter these behaviors in wildtype mice. These findings revealed an ongoing requirement for Pet-1 function in adult 5-HT neurons for transcriptional control of anxiety-like behavior.

Antipsychotic drug actions

Pet-1−/− mice have also been used in studies aimed at understanding the mechanisms of action of atypical antipsychotics. Atypical antipsychotics such as clozapine are highly efficacious in the treatment of schizophrenia but, unlike typical antipsychotics, do not trigger disabling extrapyramidal symptoms. Clozapine treatment is not without serious side effects, however, which underscores the need for development of newer atypical antipsychotics that are more effective but with fewer side effects. A critical gap in knowledge that has hindered efforts to develop better antipsychotics is the poor understanding of clozapine’s mechanism of action. A clue, however, was the finding that clozapine and the closely related atypical antipsychotic olanzapine but not the typical antipsychotic, haloperidol, display high affinity interactions with most 5-HT GPCRs and lower affinity interactions with D2, D3, and D4 dopamine receptors (Yadav et al., 2011). While these findings are consistent with the earlier postulated role of postsynaptic 5-HT receptors as substrates for clozapine action, genetic deletion of the 5-HT 2A receptor, a hypothesized principal target of clozapine, had little effect on clozapine’s antipsychotic-like properties: normalization of disrupted pre-pulse inhibition (PPI) by the non-competitive NMDA antagonist and schizophrenia mimetic, phencyclidine. To determine whether 5-HT neurons were required for atypical antipsychotic-like actions, clozapine and olanzapine were tested in Pet-1−/− mice (Yadav et al., 2011). While pretreatment of +/+ mice with clozapine or olanzapine completely normalized PCP-disrupted PPI, normalization was abolished in Pet-1−/− mice. This unexpected requirement for 5-HT neurons suggests that development of more effective atypical antipsychotics may depend on drug actions that alter pre-synaptic serotonergic activity in addition to concomitant effects on various post-synaptic receptors (Yadav et al., 2011).

5-HT Neuron heterogeneity

Classic immunohistochemical studies with anti-5-HT antisera (Lidov and Molliver, 1982, Wallace and Lauder, 1983) showed that rodent 5-HT neurons are born in two bilateral longitudinal domains on either side of the floor plate in the ventral hindbrain. The anterior or rostral domain positioned at the level of rhombomeres 1–3 was found to give rise to 5-HT neurons that populate the dorsal and median raphe while the posterior or caudal domain at r5–r8 gave rise to 5-HT neurons that coalesce into the medullary raphe nuclei. Recently, a new molecular genetic approach, intersectional and subtractive genetic lineage tracing, has provided a more precise way to define the disparate embryonic hindbrain origins of different raphe nuclei (Jensen et al., 2008). This approach took advantage of the distinct serotonergic specification programs operating at discrete axial levels of the hindbrain to follow the anatomical fate of rhombomere-specific progenitor pools. A dual Flp and Cre recombinase conditional indicator allele was combined with an ePet::FLPe driver expressing flp recombinase specifically in 5-HT neuron precursors and different rhombomere-specific Cre drivers (Kimmel et al., 2000). Cells that had an intersecting history of expressing both Flp and Cre activated a LacZ indicator allele thus identifying those mature 5-HT neurons that originated from specific rhombomeres. The findings of this study demonstrated the exclusive r1 origin of the entire dorsal raphe nucleus and revealed that the median raphe and the B9 cluster of 5-HT neurons are formed by a commingling of cells derived from progenitors that populate r1–r3. In addition, the intersectional gene expression approach offers a way to define and access subsets of hindbrain 5-HT neurons based on their distinct genetic lineages.

Different serotonergic lineages defined by intersectional fate mapping are consistent with the rich diversity of 5-HT neurons that is evident in their diverse axonal trajectories, anatomical locations, physiological properties, and molecular requirements. To directly identify the gene expression differences that might account for the diversity of serotonergic neurons whole genome expression profiling was performed on FACS purified ePet-EYFP expressing rostral and caudal 5-HT neurons (Wylie et al., 2010). This study focused exclusively on E12.5 5-HT neurons and therefore was designed to identify expression of genes that were more likely to regulate serotonergic differentiation and maturation rather than progenitor specification.

Enriched expression of hundreds of genes not previously associated with 5-HT neurons was identified. Furthermore, comparative analysis of rostral and caudal 5-HT neurons identified hundreds of genes, encoding transcription factors, axon guidance, intracellular signaling and other kinds of proteins, whose expression was differentially enriched between these two groups of neurons. For example, expression of the closely linked Hmx2 and Hmx3 homeodomain genes was detected in rostral 5-HT neurons but not caudal ones while expression of several Hox genes was detected in caudal but not rostral 5-HT neurons. These findings revealed deep molecular and potential biological pathway differences between rostral and caudal 5-HT neurons, which may be responsible for generating 5-HT neuron heterogeneity. Functional studies will be required to determine the importance of rostrocaudal gene expression heterogeneity and whether distinct homeodomain codes specify subtypes of 5-HT neurons.

Summary

The experimental accessibility of 5-HT neurons has been greatly expanded in recent years with the development and application of 5-HT neuron-type transgenic tools. These tools have made possible studies that have revealed key features of the transcriptional mechanisms that direct differentiation, maturation, and maintenance of 5-HT neurons. Genetic disruption of 5-HT neuron development and function is beginning to provide a better understanding of the physiological roles of 5-HT neurons and the impact, in vivo, of serotonergic alterations at different stages of life. The demonstration that genetic disruption of 5-HT neuron development severely impairs maternal behavior and offspring survival has challenged prevailing wisdom about the dispensability of the 5-HT system for essential physiological processes. The wide range of behavioral and physiological phenotypes arising from disruption of the transcriptional programs that generate 5-HT neurons reinforces the idea that perturbation of serotonergic gene expression is a potential avenue to vulnerability for several disorders of the nervous system. Further mapping of diverse 5-HT neuron transcriptomes and the refinement of 5-HT neuron-type genetics approaches will help to define functional neuronal heterogeneity within the serotonergic system and the precise roles of brain 5-HT subsystems in modulation of specific behaviors and physiological processes.

Highlights.

New genetics approaches have been developed to study brain serotonin neurons.

These approaches were enabled by manipulation of the Pet-1 transcription factor gene.

The Pet-1 regulatory region was used to create new 5-HT neuron-type transgenic tools

These tools have led to advances in understanding the role of serotonin in behavior

These tools have revealed transcriptional networks controlling serotonergic identity

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Steven Wyler and Drs. Richard Zigmond, Jerry Silver, Jeffery Erickson (The College of New Jersey) and Bryan Roth (University of North Carolina) for valuable comments on the manuscript. Research in the Deneris Lab is supported by RO1 MH062723 and P50 MH078028 to E.S.D.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alenina N, Kikic D, Todiras M, Mosienko V, Qadri F, Plehm R, Boye P, Vilianovitch L, Sohr R, Tenner K, Hortnagl H, Bader M. Growth retardation and altered autonomic control in mice lacking brain serotonin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:10332–10337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810793106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansorge MS, Morelli E, Gingrich JA. Inhibition of serotonin but not norepinephrine transport during development produces delayed, persistent perturbations of emotional behaviors in mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28:199–207. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3973-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM, Zhang X, Rodriguiz RM, Sotnikova TD, Cools MJ, Wetsel WC, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. Role of GSK3 beta in behavioral abnormalities induced by serotonin deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1333–1338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711496105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M, Gray JA, Roth BL. The expanded biology of serotonin. Annual review of medicine. 2009;60:355–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.042307.110802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnin A, Goeden N, Chen K, Wilson ML, King J, Shih JC, Blakely RD, Deneris ES, Levitt P. A transient placental source of serotonin for the fetal forebrain. Nature. 2011;472:347–350. doi: 10.1038/nature09972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cases O, Vitalis T, Seif I, De Maeyer E, Sotelo C, Gaspar P. Lack of barrels in the somatosensory cortex of monamine oxidase A-deficient mice: role of a serotonin excess during the critical period. Neuron. 1996;16:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Lun Y, Ovchinnikov D, Kokubo H, Oberg KC, Pepicelli CV, Gan L, Lee B, Johnson RL. Limb and kidney defects in Lmx1b mutant mice suggest an involvement of LMX1B in human nail patella syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;19:51–55. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Jonak E, Fernstrom JD. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors do not prevent 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine-induced depletion of serotonin in rat brain. Brain Res. 2004;1007:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings KJ, Li A, Deneris ES, Nattie EE. Bradycardia in serotonin-deficient Pet-1−/− mice: influence of respiratory dysfunction and hyperthermia over the first 2 postnatal weeks. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1333–1342. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00110.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai JX, Han HL, Tian M, Cao J, Xiu JB, Song NN, Huang Y, Xu TL, Ding YQ, Xu L. Enhanced contextual fear memory in central serotonin-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11981–11986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801329105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailly E, Chenu F, Petit-Demouliere B, Bourin M. Specificity and efficacy of noradrenaline, serotonin depletion in discrete brain areas of Swiss mice by neurotoxins. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;150:111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depuy SD, Kanbar R, Coates MB, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. Control of breathing by raphe obscurus serotonergic neurons in mice. J Neurosci. 2011;31:1981–1990. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4639-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding YQ, Marklund U, Yuan W, Yin J, Wegman L, Ericson J, Deneris E, Johnson RL, Chen ZF. Lmx1b is essential for the development of serotonergic neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:933–938. doi: 10.1038/nn1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson JT, Shafer G, Rossetti MD, Wilson CG, Deneris ES. Arrest of 5HT neuron differentiation delays respiratory maturation and impairs neonatal homeostatic responses to environmental challenges. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;159:85–101. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson JT, Sposato BC. Autoresuscitation responses to hypoxia-induced apnea are delayed in newborn 5-HT-deficient Pet-1 homozygous mice. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:1785–1792. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90729.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filip M, Bader M. Overview on 5-HT receptors and their role in physiology and pathology of the central nervous system. Pharmacol Rep. 2009;61:761–777. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(09)70132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyodorov D, Nelson T, Deneris E. Pet-1, a novel ETS domain factor that can activate neuronal nAchR gene transcription. J Neurobiol. 1998;34:151–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar P, Cases O, Maroteaux L. The developmental role of serotonin: news from mouse molecular genetics. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:1002–1012. doi: 10.1038/nrn1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne AL, Wylie CJ, Landmesser LT, Deneris ES, Silver J. Serotonergic neurons migrate radially through the neuroepithelium by dynamin-mediated somal translocation. J Neurosci. 2010;30:420–430. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2333-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler LK, Chu HM, Brennan TJ, Danao JA, Bajwa P, Parsons LH, Tecott LH. Elevated anxiety and antidepressant-like responses in serotonin 5-HT1A receptor mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15049–15054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks T, Francis N, Fyodorov D, Deneris E. The ETS Domain Factor Pet-1 is an Early and Precise Marker of Central 5-HT Neurons and Interacts with a Conserved Element in Serotonergic Genes. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10348–10356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10348.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks TJ, Fyodorov DV, Wegman LJ, Lelutiu NB, Pehek EA, Yamamoto B, Silver J, Weeber EJ, Sweatt JD, Deneris ES. Pet-1 ETS gene plays a critical role in 5-HT neuron development and is required for normal anxiety-like and aggressive behavior. Neuron. 2003;37:233–247. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges MR, Best S, Richerson GB. Altered ventilatory and thermoregulatory control in male and female adult Pet-1 null mice. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;177:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges MR, Richerson GB. Contributions of 5-HT neurons to respiratory control: neuromodulatory and trophic effects. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;164:222–232. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges MR, Richerson GB. The role of medullary serotonin (5-HT) neurons in respiratory control: contributions to eupneic ventilation, CO2 chemoreception, and thermoregulation. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:1425–1432. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01270.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges MR, Tattersall GJ, Harris MB, McEvoy SD, Richerson DN, Deneris ES, Johnson RL, Chen ZF, Richerson GB. Defects in breathing and thermoregulation in mice with near-complete absence of central serotonin neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2495–2505. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4729-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges MR, Wehner M, Aungst J, Smith JC, Richerson GB. Transgenic mice lacking serotonin neurons have severe apnea and high mortality during development. J Neurosci. 2009;29:10341–10349. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1963-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A. Genetic variation in cortico-amygdala serotonin function and risk for stress-related disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1293–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimura K, Takeuchi Y, Fujiwara K, Tominaga M, Yoshioka H, Sawada T. Quantitative analysis of the distribution of serotonin-immunoreactive cell bodies in the mouse brain. Neurosci Lett. 1988;91:265–270. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90691-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyo AH, Porter B, Deneris ES, Austin MC. Regional distribution and cellular localization of the ETS-domain transcription factor, FEV, mRNA in the human postmortem brain. Synapse. 2005;57:223–228. doi: 10.1002/syn.20178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob J, Ferri AL, Milton C, Prin F, Pla P, Lin W, Gavalas A, Ang SL, Briscoe J. Transcriptional repression coordinates the temporal switch from motor to serotonergic neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1433–1439. doi: 10.1038/nn1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P, Farago AF, Awatramani RB, Scott MM, Deneris ES, Dymecki SM. Redefining the serotonergic system by genetic lineage. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:417–419. doi: 10.1038/nn2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel RA, Turnbull DH, Blanquet V, Wurst W, Loomis CA, Joyner AL. Two lineage boundaries coordinate vertebrate apical ectodermal ridge formation. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1377–1389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyasova V, Fernandez SP, Laine J, Stankovski L, Muzerelle A, Doly S, Gaspar P. A Genetically Defined Morphologically and Functionally Unique Subset of 5-HT Neurons in the Mouse Raphe Nuclei. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2756–2768. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4080-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knuth ED, Etgen AM. Neural and hormonal consequences of neonatal 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine may not be associated with serotonin depletion. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;151:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegebaum CB, Gutknecht L, Bartke L, Reif A, Buttenschon HN, Mors O, Lesch KP, Schmitt AG. The expression of the transcription factor FEV in adult human brain and its association with affective disorders. J Neural Transm. 2010;117:831–836. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger KC, Deneris ES. Serotonergic transcription of human FEV reveals direct GATA factor interactions and fate of Pet-1-deficient serotonin neuron precursors. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12748–12758. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4349-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerch-Haner JK, Frierson D, Crawford LK, Beck SG, Deneris ES. Serotonergic transcriptional programming determines maternal behavior and offspring survival. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1001–1003. doi: 10.1038/nn.2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidov HGW, Molliver ME. Immunohistochemical study of the development of serotonergic neurons in the rat CNS. Brain Res Bull. 1982;9:559–604. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(82)90164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillesaar C, Stigloher C, Tannhauser B, Wullimann MF, Bally-Cuif L. Axonal projections originating from raphe serotonergic neurons in the developing and adult zebrafish, Danio rerio, using transgenics to visualize raphe-specific pet1 expression. J Comp Neurol. 2009;512:158–182. doi: 10.1002/cne.21887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillesaar C, Tannhauser B, Stigloher C, Kremmer E, Bally-Cuif L. The serotonergic phenotype is acquired by converging genetic mechanisms within the zebrafish central nervous system. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:1072–1084. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima FB, Centeno ML, Costa ME, Reddy AP, Cameron JL, Bethea CL. Stress sensitive female macaques have decreased fifth Ewing variant (Fev) and serotonin-related gene expression that is not reversed by citalopram. Neuroscience. 2009;164:676–691. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Maejima T, Wyler SC, Casadesus G, Herlitze S, Deneris ES. Pet-1 is required across different stages of life to regulate serotonergic function. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1190–1198. doi: 10.1038/nn.2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Iacono L, Gross C. Alpha-Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II contributes to the developmental programming of anxiety in serotonin receptor 1A knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6250–6257. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5219-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer P, Rorive S, de Kerchove d’Exaerde A, Schiffmann SN, Salmon I, de Launoit Y. The Ets transcription factor Fev is specifically expressed in the human central serotonergic neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2004;357:215–218. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DL, Fox MA, Timpano KR, Moya PR, Ren-Patterson R, Andrews AM, Holmes A, Lesch KP, Wendland JR. How the serotonin story is being rewritten by new gene-based discoveries principally related to SLC6A4, the serotonin transporter gene, which functions to influence all cellular serotonin systems. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:932–960. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DL, Lesch KP. Targeting the murine serotonin transporter: insights into human neurobiology. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:85–96. doi: 10.1038/nrn2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota Y, Neubauer N, Gasa R, Lynn FC, Scheel DW, Wang JH, Deneris ES, German MS. Islet ETS transcription factor Pet-1 lies in the neurogenin-NKX transcriptional cascade and binds the insulin promoterA2 element. Diabetes. 2005;54:A404. [Google Scholar]

- Parks CL, Robinson PS, Sibille E, Shenk T, Toth M. Increased anxiety of mice lacking the serotonin1A receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10734–10739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattyn A, Vallstedt A, Dias JM, Samad OA, Krumlauf R, Rijli FM, Brunet JF, Ericson J. Coordinated temporal and spatial control of motor neuron and serotonergic neuron generation from a common pool of CNS progenitors. Genes Dev. 2003;17:729–737. doi: 10.1101/gad.255803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter M, Couturier J, Pacquement H, Michon J, Thomas G, Magdelenat H, Delattre O. A new member of the ETS family fused to EWS in Ewing tumors. Oncogene. 1997;14:1159–1164. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaar H, von Holst A, Vogt Weisenhorn DM, Brodski C, Guimera J, Wurst W. mPet-1, a mouse ETS-domain transcription factor, is expressed in central serotonergic neurons. Dev Genes Evol. 2002;212:43–46. doi: 10.1007/s00427-001-0208-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popa D, Lena C, Alexandre C, Adrien J. Lasting Syndrome of Depression Produced by Reduction in Serotonin Uptake during Postnatal Development: Evidence from Sleep, Stress, and Behavior. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3546–3554. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4006-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramboz S, Oosting R, Amara DA, Kung HF, Blier P, Mendelsohn M, Mann JJ, Brunner D, Hen R. Serotonin receptor 1A knockout: an animal model of anxiety-related disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14476–14481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson-Jones JW, Craige CP, Guiard BP, Stephen A, Metzger KL, Kung HF, Gardier AM, Dranovsky A, David DJ, Beck SG, Hen R, Leonardo ED. 5-HT1A autoreceptor levels determine vulnerability to stress and response to antidepressants. Neuron. 2010;65:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson-Jones JW, Craige CP, Nguyen TH, Kung HF, Gardier AM, Dranovsky A, David DJ, Guiard BP, Beck SG, Hen R, Leonardo ED. Serotonin-1A Autoreceptors Are Necessary and Sufficient for the Normal Formation of Circuits Underlying Innate Anxiety. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6008–6018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5836-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein JL. Development of serotonergic neurons and their projections. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:145–150. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaco RC, Mandel-Brehm C, Chao HT, Ward CS, Fyffe-Maricich SL, Ren J, Hyland K, Thaller C, Maricich SM, Humphreys P, Greer JJ, Percy A, Glaze DG, Zoghbi HY, Neul JL. Loss of MeCP2 in aminergic neurons causes cell-autonomous defects in neurotransmitter synthesis and specific behavioral abnormalities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21966–21971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912257106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savelieva KV, Zhao S, Pogorelov VM, Rajan I, Yang Q, Cullinan E, Lanthorn TH. Genetic disruption of both tryptophan hydroxylase genes dramatically reduces serotonin and affects behavior in models sensitive to antidepressants. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer TL, Vorhees CV, Williams MT. Mouse plasmacytoma-expressed transcript 1 knock out induced 5-HT disruption results in a lack of cognitive deficits and an anxiety phenotype complicated by hypoactivity and defensiveness. Neuroscience. 2009;164:1431–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott MM, Deneris ES. Making and breaking serotonin neurons and autism. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott MM, Krueger KC, Deneris ES. A differentially autoregulated Pet-1 enhancer region is a critical target of the transcriptional cascade that governs serotonin neuron development. J Neurosci. 2005a;25:2628–2636. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4979-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott MM, Wylie CJ, Lerch JK, Murphy R, Lobur K, Herlitze S, Jiang W, Conlon RA, Strowbridge BW, Deneris ES. A genetic approach to access serotonin neurons for in vivo and in vitro studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005b;102:16472–16477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504510102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song NN, Xiu JB, Huang Y, Chen JY, Zhang L, Gutknecht L, Lesch KP, Li H, Ding YQ. Adult raphe-specific deletion of lmx1b leads to central serotonin deficiency. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-John WM, Li A, Leiter JC. Genesis of gasping is independent of levels of serotonin in the Pet-1 knockout mouse. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:679–685. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91461.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankovski L, Alvarez C, Ouimet T, Vitalis T, El-Hachimi KH, Price D, Deneris E, Gaspar P, Cases O. Developmental cell death is enhanced in the cerebral cortex of mice lacking the brain vesicular monoamine transporter. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1315–1324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4395-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbusch HWM. Distribution of serotonin-immunoreactivity in the central nervous system of the rat-cell bodies and terminals. Neuroscience. 1981;6:557–618. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(81)90146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga V, Losonczy A, Zemelman BV, Borhegyi Z, Nyiri G, Domonkos A, Hangya B, Holderith N, Magee JC, Freund TF. Fast synaptic subcortical control of hippocampal circuits. Science. 2009;326:449–453. doi: 10.1126/science.1178307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JA, Lauder JM. Development of the serotonergic system in the rat embryo: an immunocytochemical study. Brain Res Bull. 1983;10:459–479. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(83)90144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther DJ, Peter JU, Bashammakh S, Hortnagl H, Voits M, Fink H, Bader M. Synthesis of serotonin by a second tryptophan hydroxylase isoform. Science. 2003a;299:76. doi: 10.1126/science.1078197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther DJ, Peter JU, Winter S, Holtje M, Paulmann N, Grohmann M, Vowinckel J, Alamo-Bethencourt V, Wilhelm CS, Ahnert-Hilger G, Bader M. Serotonylation of small GTPases is a signal transduction pathway that triggers platelet alpha-granule release. Cell. 2003b;115:851–862. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YC, Zuraek MB, Kosaka Y, Ota Y, German MS, Deneris ES, Bergsland EK, Donner DB, Warren RS, Nakakura EK. The ETS oncogene family transcription factor FEV identifies serotonin-producing cells in normal and neoplastic small intestine. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010 doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie CJ, Hendricks TJ, Zhang B, Wang L, Lu P, Leahy P, Fox S, Maeno H, Deneris ES. Distinct transcriptomes define rostral and caudal serotonin neurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:670–684. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4656-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav PN, Abbas AI, Farrell MS, Setola V, Sciaky N, Huang XP, Kroeze WK, Crawford LK, Piel DA, Keiser MJ, Irwin JJ, Shoichet BK, Deneris ES, Gingrich J, Beck SG, Roth BL. The presynaptic component of the serotonergic system is required for clozapine’s efficacy. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:638–651. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZQ, Scott M, Chiechio S, Wang JS, Renner KJ, Gereau RWt, Johnson RL, Deneris ES, Chen ZF. Lmx1b is required for maintenance of central serotonergic neurons and mice lacking central serotonergic system exhibit normal locomotor activity. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12781–12788. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4143-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]