Abstract

Background

Native (pre-existing) collaterals are arteriole-to-arteriole anastomoses that interconnect adjacent arterial trees and serve as endogenous bypass vessels that limit tissue injury in ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, coronary and peripheral artery disease. Their extent (number and diameter) varies widely among mouse strains and healthy humans. We previously identified a major quantitative trait locus on chromosome 7 (Canq1, LOD = 29) responsible for 37% of the heritable variation in collateral extent between C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice. We sought to identify candidate genes in Canq1 responsible for collateral variation in the cerebral pial circulation, a tissue whose strain-dependent variation is shared by similar variation in other tissues.

Methods and Findings

Collateral extent was intermediate in a recombinant inbred line that splits Canq1 between the C57BL/6 and BALB/c strains. Phenotyping and SNP-mapping of an expanded panel of twenty-one informative inbred strains narrowed the Canq1 locus, and genome-wide linkage analysis of a SWRxSJL-F2 cross confirmed its haplotype structure. Collateral extent, infarct volume after cerebral artery occlusion, bleeding time, and re-bleeding time did not differ in knockout mice for two vascular-related genes located in Canq1, IL4ra and Itgal. Transcript abundance of 6 out of 116 genes within the 95% confidence interval of Canq1 were differentially expressed >2-fold (p-value<0.05÷150) in the cortical pia mater from C57BL/6 and BALB/c embryos at E14.5, E16.5 and E18.5 time-points that span the period of collateral formation.

Conclusions

These findings refine the Canq1 locus and identify several genes as high-priority candidates important in specifying native collateral formation and its wide variation.

Introduction

Ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction and atherosclerotic disease of arteries supplying the brain, heart and lower extremities are leading causes of morbidity and mortality. Recently, variation in the density and diameter (extent) of the native pre-existing collaterals present in a tissue have become recognized as important determinants of the wide variation in severity of tissue injury caused by these diseases [1]–[4]. Collaterals are arteriole-to-arteriole anastomoses that are present in most tissues and cross-connect a small fraction of distal-most arterioles of adjacent arterial trees. After acute obstruction of an arterial trunk, collateral extent dictates the amount of retrograde perfusion from adjacent trees thus severity of ischemic injury. With chronic obstruction, native collaterals undergo anatomic lumen enlargement, a process termed collateral remodeling or arteriogenesis that requires days-to-weeks to reach completion, resulting in an increase in conductance of the collateral network [5].

Surprisingly, native collateral extent differs widely among “healthy” individuals, ie, those free of stenosis of arteries supplying the heart or brain. Thus coronary collateral flow (ie, CFIp) varies more than 10-fold in individuals without coronary artery disease [4], [6]. Likewise, large differences in collateral-dependent cerebral blood flow are evident in individuals after sudden embolic stroke [2], [3], [7]. Moreover, direct measurement of native collateral extent shows that it varies widely among healthy inbred mouse strains [8]–[10]. Variation in healthy humans and mice can be attributed to genetic differences affecting mechanisms that control formation of the collateral circulation, which in mouse occurs late in gestation [11], [12], and to differences in environmental influences and cardiovascular risk factors that recent studies are finding affect persistence of these vessels in adults [13], [14].

We previously identified a prominent QTL on chromosome 7 (Canq1, LOD = 29) responsible for 37% of the heritable variation in collateral extent (as well as collateral remodeling) in the cerebral circulation of C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice [15]—strains which exhibit the widest difference among 15 strains examined [9]. Moreover, these same 15 strains had an equally wide variation in infarct volume after middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion that was tightly and inversely correlated with collateral density and diameter, thus establishing a strong causal relationship between severity of stroke and collateral extent [9], [16]. Three other loci were responsible for an additional 35% of the variation in collateral extent [15]. Importantly, genetic-dependent differences in collateral extent in the cerebral circulation are shared by similar variation in other tissues, at least in mice [8], [10], [17], [18]. Consistent with this, Canq1 maps to the same location on chromosome 7 as recently reported QTL linked to hindlimb ischemia (LSq1) [19] and cerebral infarct volume (Civq1) [16]. Thus, our findings [15] identify the physiological substrate, variation in collateral extent that underlies these QTL.

Efficient Mixed-model Association Mapping with high-density SNPs for the above 15 strains allowed us to narrow Canq1 to a region (“EMMA region”) [15]. In the present study we sought to further refine this locus and the candidate genes potentially responsible for collateral variation. Identification of the causal genetic element(s) will reveal key signaling pathways controlling collateral formation—about which little is known [1], [12], [17]. Moreover, if subsequently confirmed in humans, this information will aid patient stratification, clinical decision making, and the development of collaterogenic therapies. To this end, we strengthened our association mapping over Canq1 using additional inbred strains, performed linkage analysis of a second genetic mapping population, measured collateral extent and infarct volume in mice genetically deficient for several candidate genes, and examined expression of 116 genes spanning the EMMA region and Canq1 in the pial circulation of mouse embryos during the period when the collateral circulation forms.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Mouse strains (male, ∼10 weeks-old): LP/J, NON/ShiLtJ (NON), LEWES/EiJ, 129X1/SvJ (129X1), CAST/EiJ, C57BL/6J (B6), BALB/cByJ (Bc), Itgal−/− (#005257, B6 background), Il4−/− (#002518, B6 background), Il4ra−/− (#003514, Bc background) and CXB11.HiAJ (CxB11) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. PWD were a gift of Dr. Fernando Pardo-Manuel, UNC. F1 progeny obtained from reciprocal mating of SWR/J (SWR) and SJL/J (SJL) were mated to produce a 10-week old F2 reciprocal population. This study was approved by the University of North Carolina's Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee and was performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Phenotyping

Mice were phenotyped for collateral number, diameter and cerebral artery tree territories as described previously [15] (Materials and Methods S1).

Association Mapping

As detailed previously [15], the EMMA algorithm [20], [21] was applied in the R statistical package to collateral number, obtained from 21 inbred strains comprised of 15 previously reported strains [9] plus 6 newly phenotyped strains. Known and imputed dense SNP data were downloaded from http://phenome.jax.org/db/q?rtn=snps/download and http://compgen.unc.edu/wp/ and pooled. The kinship matrix (pair-wise relatedness) among the 21 inbred strains was calculated using the dense SNP-set within the Canq1 region, and modeled as random effects [22]. Each SNP within Canq1 was modeled as a fixed effect. After the mixed model was fitted, an F-test was conducted and a p-value obtained at each SNP location.

DNA Isolation, Genotyping and Linkage Analysis

Tail genomic DNA from SWRxSJL-F2 mice (n = 123) was genotyped using the 377-SNP GoldenGate genotyping array (Illumina, San Diego, CA). SNP positions were obtained from Build 37.1 of the NCBI SNP database. There are 324 informative markers on 19 autosomes in this array, including 29 on Chr 7 with 6 between 121.5 and 144.5 thus 1 every ∼4 Mb. Collateral number was subjected to linkage analysis using the single QTL model in the R statistical package [15]. Threshold for significant QTL was defined as p = 0.05.

Bleeding and Re-bleeding Assays

Bleeding (thrombosis) and re-bleeding (thrombolysis) assays were similar to previous methods [23]. Under 1.2% isoflurane anesthesia supplemented with oxygen and with rectal temperature maintained at 37°C, the tail was pre-warmed for 5 min in 50 mL of 37°C saline. A 5 mm length from the tip of the tail was amputated with a fresh sterile #11 scalpel blade, and the tail was immediately returned to the saline. The cut surface was positioned 10 mm below the ventral surface of the body. Bleeding time was the time between the beginning and cessation of bleeding. Re-bleeding time was the time between cessation and resumption of bleeding.

Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion and Measurement of Infarct Volume

These were done as detailed previously [15] (Materials and Methods S1).

Gene Expression

B6 and Bc breeders were paired at 10–12 weeks-age. The presence of a vaginal plug the morning after pairing was designated as 0.5 days post-coitus (E0.5). Embryos were collected at E14.5, E16.5 and E18.5 under deep anesthesia (ketamine+xylazine, 100+15 mg/kg) and staged according to crown-to-rump length. Brains were quickly removed into RNAlater® (Sigma-Aldrich Corp, St. Louis, MO) and stored at −20°C. Approximately 24 hours later the pia mater containing the pial circulation was peeled from the dorsal cerebral cortex of both hemispheres under a stereomicroscope and stored in RNAlater® at −20°C. Pia from 8–10 embryos of each strain were pooled for each RNA sample (≥2 litters per pool). Three pooled RNA samples were prepared for each strain and time-point (18 samples; ∼100 embryos/strain). Samples were thawed in RNAlater and homogenized (TH, Omni International, Marietta, GA) in Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Total RNA was purified using the RNeasy Micro Kit according to the manufacturer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA concentration and quality were determined by NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE) and Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Foster City, CA), respectively. Measurement of transcript number was conducted for 139 selected genes and 11 splice variants by the genomics facility at UNC using NanoString custom-synthesized probes (NanoString, Seattle, WA) [24], [25]. Transcript number for each gene was normalized to the mean of 6 housekeeping genes: Gapdh, βactin, Tubb5, Hprt1, Ppia and Tbp.

For quantitative RT-PCR, reverse transcription was performed with SuperScript™ First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, # 11904-018) following the manufacturer's instructions. Amplification was achieved with SYBR® Green JumpStart™ Taq ReadyMix™ (Sigma, #S4438) on a Rotor-Gene 3000 (Corbett Life Science). Samples were analyzed in triplicate and values averaged. Primer sequences are listed in Table S1. Data were analyzed using the Relative Expression Software Tool 2009 (version 2.0.13) and calculations as described [26].

Statistical Analysis

Values are mean±SEM. Significance was p<0.05 unless stated otherwise. ANOVA and Student's t-tests were used as indicated in the figures and tables. For analysis of expression: (1) transcript numbers for strain and embryonic time-point were subjected to 2-way ANOVA, with Bonferroni adjustment of p-values for multiple comparisons (p-values÷150, for 150 transcripts). (2) ANOVA p-values were also derived after correction with the Bonferroni inequality for pre-planned post-hoc tests for 2 strains and 3 time points. (3) Student's t-tests were used to test effect of strain independent of time, with and without Bonferroni adjustment (p-values÷150). Statistical treatment of association mapping data was as described [15].

Results

Collateral Number in CXB11.HiAJ RIL Verifies Canq1 on Chromosome 7

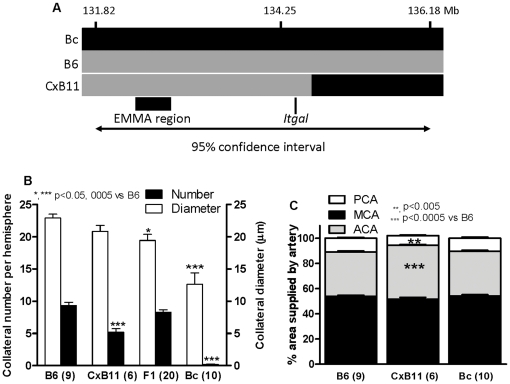

The CxB recombinant inbred lines (RILs) originated from Bc and B6 parentals [27]. Among them, CxB11.HiAJ (CxB11) is particularly relevant. Given the unique mosaic genetic structure for each RIL, we hypothesized that if Canq1 in general, and the “EMMA region” [15] in particular, are determinants of collateral extent, an RIL that inherits this locus from either B6 (abundant large-diameter collaterals) or Bc (sparse small-diameter collaterals) [8]–[10], [15] will exhibit traits dominated by the parental phenotype. CxB11 splits Canq1 such that the centromeric half of Canq1 and the EMMA region are from B6 ( Figure 1A ). These results confirm our previous findings [15] showing the importance of Canq1 and the EMMA region for specifying collateral extent.

Figure 1. Collateral extent in CXB11.HiAJ (CxB11) confirms importance of Canq1.

A, Inheritance patterns of Cang1 on chromosome 7 in CxB11 recombinant inbred line derived from BALB/c (Bc)×C57BL/6 (B6). Y axis, SNP positions (Build 37). CxB11 inherits from B6 the segment (B6, grey; Bc, black) that includes the EMMA region and extends through Itgal. B, Collateral number is intermediate between B6 and Bc in CxB11 and significantly different from B6xBc-F1. C, Territory of cerebral cortex supplied by the ACA, MCA, and PCA trees. B6 and Bc are identical (confirms Zhang et al. [9]), while CxB11 has smaller MCA and PCA and larger ACA territory than B6. These differences do not correlate with variation in collateral number or diameter in these or 15 other strains [9]. Numbers of mice given in parentheses in this and other figures.

Because area (“size”) of the MCA, ACA, and PCA trees varies with genetic background and could contribute to variation in collateral extent [9], we measured the percentage of cortical territory supplied by each tree. Values for CxB11 (Figure 1C) fall within the range of differences that have no correlation with variation in collateral extent; also, the parental strains are identical as reported previously [9]. Thus, variation in tree size cannot explain the CxB11 results.

Additional Inbred Strains Strengthen and Refine the EMMA Region

EMMA mapping is more efficient computationally and accounts better for population structure embedded in inbred strains, when compared to traditional association mapping algorithms [21]. We previously applied this algorithm to 15 inbred strains and obtained a most-significant 172 kb region (EMMA-A, p = 2.2×10−5) and a second-most significant region (EMMA-B, 290 kb, p = 4.2×10−4) [15]. To strengthen this analysis, we first generated a heatmap of the known and imputed SNPs within EMMA-A for 74 inbred strains (Figure S1). The 15 strains lowest on the y-axis are those used previously [15]. The lowest 5 have significantly fewer collaterals than B6. Among the 15 strains, 9 out of 10 with high collateral number exhibit a DNA haplotype-like block similar to B6 ( Figure 2 , blue), whereas all 5 strains with low collateral number exhibit a haplotype-like block similar to Bc (Figure 2, mostly green). The exception is SJL/J (discussed below). To test the robustness of the EMMA-A region for variation in collateral number, we chose the 6 most informative additional inbred strains from the 74 lines (denoted red in Figure 2): 3 strains with haplotype structures predicting high (129X1, LP, NON) and low (CAST/Ei, PWD, LEWES/Ei) collateral number. Collateral numbers in 4 of these strains fit the prediction from their haplotype structures (Figure S2). The remaining two are wild-derived strains that have more complex ancestry and haplotype structures.

Figure 2. Collateral number for 21 inbred strains and heatmap of their SNPs within the EMMA region.

Left, Heatmap of known and imputed SNPs for 21 strains in EMMA region (blue, SNP same as B6; green, different from B6; blank, genotype unknown). Right, Collateral number per hemisphere for 21 strains. Names in red denote newly phenotyped strains, black names are strains from Zhang et al. [9]. N = 8–10/strain. Dashed line, reference to B6.

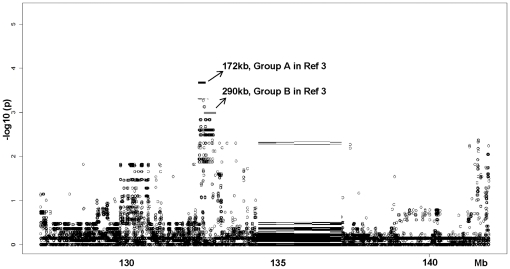

An important consideration is whether the EMMA-A peak shifts position or if the significant SNPs change their p-values from our previous findings [15] after the additional 6 strains are remapped with the original 15. Figure 3 shows that EMMA-A did not change position, that the previous EMMA-A peak was narrowed further, and that the new peak acquired increased significance for the same SNPs (p = 9×10−6).

Figure 3. Six more strains strengthen and narrow the EMMA interval.

The EMMA algorithm was applied to collateral number for the 21 strain data set, ie, 6 new strains (red strains in Figure 2) plus 15 from Zhang et al. [9]. ∼49,000 high quality imputed SNPs under the Canq1 peak were tested. The previous highly significant region was strengthened and narrowed (p<9×10−6, 4 SNPs). Black bars indicate the most (Group A) and second most (Group B) significant regions in the previous study [15]. Mapping allowed fewer than three SNPs with missing genotypes.

The kinship matrix used to account for population structure will vary with use of different SNPs as new strains are considered [22]. Furthermore, we previously did not allow missing genotypes to avoid a decrease in statistical power [15]. We thus examined the effect of several parameters on our new mapping results by: allowing fewer than 3 missing genotypes in the strains; using only informative SNPs; excluding wild-derived strains. Irrespective of these mapping parameters, 4 SNPs always had the most significant p-values (rs32978185, rs32978627, rs32973294, and rs32973297; 132.502–132.504 Mb; Figures S3, S4, S5, S6, S7).

Genome-wide QTL Mapping of SWRxSJL-F2 Shows Absence of Canq1

Strains SJL and SWR have identical Bc-like haplotype structures in the EMMA regions, but SJL averages 9.6Á±0.4 collaterals per hemisphere while SWR averages 1.3±0.4 ( Figure 4 ). To test the validity of the EMMA regions and possibly identify additional QTL, we created a SWRxSJL-F2 cross and performed genome-wide LOD score profiling of collateral number-by-genotype. As predicted, we found no QTL on Chr 7 (Figure 4). We also found no QTL elsewhere in the genome. We did not measure collateral diameter because 1) of the time required to obtain average collateral diameter for each of the 123 F2 mice, 2) we have shown that variation in collateral number and diameter map to the same Canq1 locus [15], 3) collateral diameter has a much smaller range of variation than number, thus lower LOD score [15], and 4) no significant QTL was found for collateral number (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Genome-wide mapping of collateral number in 123 SWRxSJL-F2 mice.

Top panel, Collateral number per hemisphere among 15 strains of mice (from Figure 2). Middle panel, Green = known and high-quality imputed (p>0.90) SNPs common to both strains and BALB/c. White, known and low-quality SNPs different between the two strains, including two common regions with “no useful data”, per JAX website (red). Lower panel, LOD profiling using single QTL model. Locations of genotyping SNPs are shown as ticks on the abscissa. 95% confidence level (dashed line) was estimated using 1000 permutations. Insert shows the range of collateral number between the MCA and ACA trees per hemisphere on the abscissa (bin range = 3–14), and number of mice having a given collateral number bin on the ordinate (range 2–23).

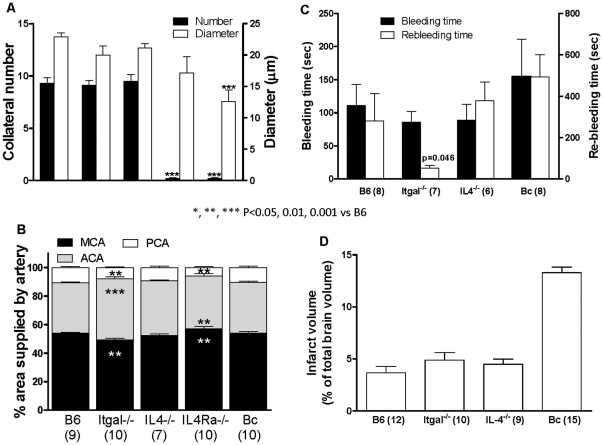

Collateral Extent, Hemostasis and Infarct Volume in Il4ra−/−, Il4−/− and Itgal−/− Do Not Support these Genes as Candidates for Canq1

Collateral extent in the adult is determined by mechanisms that specify their formation in the embryo. Recent studies indicate that Vegfa, Clic4, Flk1, Adam10 and Adam17 are important in this process [11], [12], [17], [18]. However, none of these genes nor others known to impact their expression or signaling pathways are located in EMMA-B, with the exception of IL4ra (interleukin 4 receptor alpha chain). Expression of Il4ra is lower in Bc compared to B6 (see below). Moreover, IL4rα is present on endothelial cells (and other cell types) where it dimerizes with IL13rα or γc to mediate responses to IL4 and IL13. These include increased expression of VEGF-A; furthermore, hypoxia-induced VEGF-A expression and angiogenesis are reduced in Il4−/− mice [28]–[30]. We thus examined Il4−/− (B6 background) and Il4ra−/− (only available on Bc background) mice. Collateral extent in Il4−/− mice (9.5 collaterals, 21 um diameter) was not different from B6 (9.3 and 23 um) ( Figure 5 ). Likewise, collateral extent in Il4ra−/− mice (0.2 collaterals, 17 um) was similar to Bc (0.2 and 13 um). These results do not support involvement of IL4ra in variation of collateral extent. Knockout mice are not available for the other genes (see below) in EMMA-B.

Figure 5. Collateral extent is not altered in Itgal, IL4 or IL4ra deficient mice relative to host strains.

A, Itgal−/− and Il4−/− mice are B6 while Il4ra−/ − (receptor alpha) are Bc background. Number and diameter are not significantly different among Itgal−/−, Il4 −/− and B6, nor between Il4ra−/− and Bc (t-tests). B, Territory (size) of ACA, MCA, and PCA trees are same in B6 and Bc but differ in Itgal−/− and Il4ra−/ −, confirming dissociation of collateral and tree territory phenotypes among inbred mouse strains [9]. C,D, Bleeding and infarct volume of knockouts are not different from B6; re-bleeding in Il4−/− is not different from B6 but shorter in Itgal−/− (t-tests).

Given the limitations of any mapping algorithm, it is possible that a genetic element(s) outside of EMMA-B could underlie Canq1. Several findings identify Itgal (integrin α-L chain, CD11a) as a candidate. Itgal is located at 134 Mb near the peak of Canq1. Itgal dimerizes with integrin β2-chain (CD18) to form LFA-1 which is present on platelets and most leukocyte types and binds ICAM1 on endothelial cells, leading to firm adhesion and transmigration [31], [32]. Keum and Marchuk identified Itgal as a candidate gene within the Civq1 QTL for infarct volume measured 24 hours after permanent MCA occlusion in a B6xBc-F2 population [16], and Itgal−/− mice have smaller infarct volumes 24 hours after 1-hour transient MCA occlusion model [32]. However, Itgal−/− mice had the same collateral extent as B6 controls (Figure 5). Consistent with this, infarct volume 24 hours after permanent MCA occlusion was not different in Itgal−/− mice (Figure 5). Infarct volume was also not affected in Il4−/− mice (B6 background; Figure 5), in agreement with no effect on collateral extent. These findings do not support Itgal or Il4ra as candidate genes for Canq1 [15] or Civq1 [16].

Variation in MCA tree size among strains is also a determinant of variation in infarct volume after permanent [9] or transient [33] MCA occlusion. MCA tree size was smaller in Itgal−/− mice (Figure 5), which may contribute to their smaller infarct volume after transient MCA occlusion [32].

The involvement of other factors besides collateral extent in determining severity of brain ischemia after acute occlusion could underlie previous [31] findings. Leukocyte/platelet adhesion and hemostasis have complex influences on infarct volume, especially after transient occlusion, through effects on thrombosis and thrombolysis (ie, hemostasis) and inflammation [33], [34]. Moreover, thrombosis and thrombolysis vary with genetic background [23]. Because these mechanisms could be affected in Itgal−/− and IL4−/− mice, we measured bleeding and re-bleeding time to assay thrombosis and thrombolysis, respectively. No differences were observed among knockouts and B6 controls (Figure 5), with the exception of shorter time to re-bleeding in Itgal−/− mice (discussed below). Depending on models and severity of stroke, increased thrombolysis can either reduce no-reflow and lessen infarct volume, or increase petechial hemorrhage and no-reflow and increase infarct volume [33], [34]. IL4ra−/− mice were not analyzed for bleeding and re-bleeding because of their cost, because IL4−/− showed no differences in these assays, and because the data in Panels A and B of Figure 5, where both IL4−/− and IL4ra−/− mice were studied, provided no support for these genes in the difference in collateral extent in mice.

We also studied hindlimb ischemia [10] in Il4−/−, Itgal−/− and their B6 background strain (Figure S8) and obtained results in agreement with the above cerebral studies for lack of effect on native collateral extent in a second tissue—skeletal muscle. Although not the subject of this study, recovery of blood flow was less in Il4−/− mice, suggesting reduced collateral remodeling (see Figure S8 for relevant references). Blood differential cell count (Table S2) identified that Itgal−/− (but not IL4−/−) mice have reduced platelets compared to their B6 background strain, which may contribute to their shorter re-bleeding time (Figure 5); they also have increased total leukocytes, lymphocytes, granulocytes and monocytes, which has been reported previously (see Table S2 for corroborating references).

Expression of Genes within Canq1

A plausible explanation for the strong effect of the Canq1 locus is that a gene(s) with strong influence on collateral extent is differentially expressed between B6 and Bc. To begin to identify possible candidates, we measured transcript levels of genes within Canq1 containing SNPs in their coding and 2 Kb flanking regions from the pial circulation of B6 and Bc embryos at E14.5, E16.5 and E18.5. Collaterals begin to form as a plexus between the crowns of the cerebral artery trees at E14.5 and reach peak density by E18.5 [11], [12]. Bc embryos form ∼90% fewer collaterals than B6, resulting in a similar large difference in collateral number and diameter in the adult [12]. We thus reasoned that expression would need to be examined at the time collaterals form. Four groups of genes were examined: all genes and splice variants annotated within EMMA-A/B (group I, 10 genes and 5 splice variants; Table S3); genes with SNP variation between B6 and Bc strains in coding or regulatory regions (ie, 2 kb 5′ and 3′ to coding) within the 95% CI of Canq1 (group II, 106 genes and 6 splice variants); selected genes located elsewhere in the genome that are angiogenesis-related (group III, 13 genes) and proliferation-related (group IV, 10 genes).

Among those examined, 1 gene in EMMA-B (Nsmce1), 6 genes located within the 95% CI of Canq1 (Pycard, Inpp5f, Tbx6, 3 “Riken genes”) and one located elsewhere (Tert, telomerase) had adjusted p-values less than 0.05 for a difference between strains at all 3 time-points using the most stringent analysis, ie, 2-way ANOVA plus Bonferroni adjusted p-value÷150 (star-labeled bars in Figure 6 ; Table 1 ; Table S3). All but Inpp5f were more than 2-fold different between B6 and Bc. Nsmce1 has three splicing isoforms, with two expressing 2.5-to-7-fold higher levels in Bc. Ino80e was differentially expressed >2-fold at all time-points, but not significant (although significant with other tests, see below). Il4ra and Il21r in EMMA-B were only significant by t-test (Tables S4 and S5).

Figure 6. Fold changes between BALB/c and C57BL/6 in mRNA levels of genes within Canq1 and selected angiogenic- and proliferation/aging-related genes at embryonic day E14.5, E16.5 and E18.5.

The numbers 1–150 at top denote gene numbers in Table 1 and Table S2. Y-axis, fold changes; Bc vs B6 if positive, B6 vs Bc if negative. Genes 1–127 located in 95% CI of Canq1 are arranged in order of physical location. I, genes within the EMMA region (132.356–132.528 Mb); II, genes in 95% CI of Canq1; III, angiogenic-related genes; IV, proliferation-related genes. Black curve, negative logarithm Bonferroni-adjusted p-values (p-value÷150) for strain effect in 2-way ANOVA; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 (÷150). Letters above bars denote significance derived from p-values for 2-way ANOVA for strain after Bonferroni inequality corrected post-hoc tests; A, p.strain<0.001, B, p.strain<0.01.

Table 1. Genes having differential expression either between strains or among different embryonic days.

| Gene* number | Name | Description | Gene† Group | Start | Fold‡ E14.5 | Fold‡ E16.5 | Fold‡ E18.5 | Bonadj§ strain | Bonadj§ Eday |

| 111 | Pycard | PYD and CARD domain containing Gene | II | 135135617 | −2.29 | −1.67 | −1.79 | 0.0003 | 0.0595 |

| 124 | Inpp5f | inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase F | II | 135754842 | 1.90 | 1.69 | 2.30 | 0.0036 | 1.0000 |

| 47 | Tbx6 | T-box 6 | II | 133924997 | 2.38 | 2.09 | 2.89 | 0.0055 | 1.0000 |

| 16 | D430042O09Rik-204 | RIKEN cDNA D430042O09 gene | II | 132851390 | 3.94 | 2.61 | 3.65 | 0.0073 | 1.0000 |

| 9 | Nsmce1-003 | non-SMC element 1 homolog | I | 132611154 | 5.54 | 3.58 | 7.09 | 0.0084 | 1.0000 |

| 150 | telomerase | NM_009354.1 | IV | 73764438 | 3.99 | 2.14 | 3.87 | 0.0085 | 1.0000 |

| 8 | Nsmce1-002 | non-SMC element 1 homolog | I | 132611154 | 2.52 | 2.05 | 3.57 | 0.0122 | 1.0000 |

| 26 | Nfatc2ip | nuclear factor calcineurin-dependent 2 interacting protein | II | 133526368 | 1.68 | 1.69 | 2.05 | 0.0125 | 1.0000 |

| 55 | Taok2 | TAO kinase 2 | II | 134009192 | 1.65 | 1.38 | 1.97 | 0.0143 | 1.0000 |

| 110 | B230325K18Rik | RIKEN cDNA B230325K18 | II | 135126593 | 9.69 | 4.68 | 7.75 | 0.0165 | 1.0000 |

| 91 | 1700120K04Rik | RIKEN cDNA 1700120K04 gene | II | 134747592 | 3.37 | 1.99 | 2.35 | 0.0177 | 1.0000 |

| 80 | 9130019O22Rik | RIKEN cDNA E430018J23 gene | II | 134525774 | 3.63 | 2.28 | 3.78 | 0.0190 | 1.0000 |

| 87 | 1700008J07Rik | non-coding RNA | II | 134655683 | 2.64 | 1.87 | 3.05 | 0.0202 | 1.0000 |

| 120 | BC017158 | UPF0420 protein C16orf58 homolog | II | 135414893 | 1.56 | 1.43 | 1.67 | 0.0226 | 1.0000 |

| 140 | Vegfa188 | vascular endothelial growth factor A | III | 46153942 | 1.88 | 1.45 | 2.05 | 0.0236 | 1.0000 |

| 88 | Phkg2 | phosphorylase kinase, gamma 2 | II | 134716854 | 1.70 | 1.34 | 2.19 | 0.0250 | 1.0000 |

| 19 | D430042O09Rik-209 | RIKEN cDNA D430042O09 gene | II | 132851390 | 2.04 | 2.09 | 5.63 | 0.0284 | 1.0000 |

| 41 | Giyd2 | GIY-YIG domain containing 2 | II | 133832982 | 1.57 | 1.63 | 2.40 | 0.0291 | 1.0000 |

| 54 | Ino80e | INO80 complex subunit E | II | 133995094 | 4.64 | 2.71 | 3.79 | 0.0343 | 1.0000 |

| 127 | Dock1 | dedicator of cytokinesis 1 | II | 141862370 | 1.87 | 2.15 | 2.47 | 0.0384 | 1.0000 |

| 122 | Tial1 | Tia1 cytotoxic granule-associated RNA binding protein-like 1 | II | 135583291 | 2.02 | 1.54 | 2.12 | 0.0418 | 1.0000 |

| 109 | Fus | malignant liposarcoma gene | II | 135110971 | 1.47 | 1.49 | 1.72 | 0.0428 | 0.6911 |

| 40 | Sult1a1 | sulfotransferase family 1A, phenol-preferring, member 1 | II | 133816379 | −2.29 | 1.01 | 1.76 | 1.0000 | 0.0026 |

| 129 | Angpt2 | angiopoietin 2 | III | 18690263 | −1.15 | 1.14 | 1.61 | 1.0000 | 0.0077 |

| 139 | Tgfb1 | Transforming gr factor β binding protein 1 | III | 75404869 | 1.30 | 1.18 | 1.32 | 0.1245 | 0.0087 |

| 37 | Nupr1 | nuclear protein 1 | II | 133766763 | −1.72 | 1.21 | 1.70 | 1.0000 | 0.0096 |

| 65 | Qprt-001 | quinolinate phosphoribosyltransferase | II | 134250628 | −1.55 | −1.19 | 1.10 | 1.0000 | 0.0377 |

| 20 | AC150648.2 | GSG1-like | II | 133024217 | −1.59 | −1.28 | −1.27 | 1.0000 | 0.0448 |

Expression assay by NanoString nCounter. 3 RNA samples of pia at each time point for each strain, with each sample composing of ≥8 embryos from ≥2 litters (18 samples, ∼200 embryos). Transcript number for each gene normalized to mean transcript number for 6 housekeeping genes: βactin, Gapdh, Tubb5, Hprt1, Ppia, Tbp.

I, genes in EMMA region; II, genes in 95% CI of Chr 7 QTL; III, angiogenic-related genes located elsewhere in genome; IV, proliferation-related genes located elsewhere in genome.

Fold change for Bc vs B6 if positive and B6 vs Bc if negative.

Bonferroni-adjusted p values (p-value÷150, for 150 genes/splice forms assayed) from 2-way ANOVA for 2 strains (20 genes p<0.05) and 3 embryonic days (6 genes p<0.05).

Expression of 6 genes changed with embryonic time but not strain (listed last in Table 1). Changes in two of these, Angpt2 (angiopoietin-2) and Tgfb1 (Ltbp1), have well-known roles in vascular development. Thus, the expected changes serve as a control for the NanoString assay. In addition, we confirmed results with qRT-PCR [24], [25], using the above RNA samples from Bc embryos (insufficient RNA prevented qRT-PCR for additional genes or for B6 embryos). Fold-expression values at E18.5 relative to E14.5 for Angpt2, Tgfb1 and Klf4 (normalize to β-actin) were 4.0±0.7, 3.3±0.9 and 0.7±0.1 by NanoString; and 3.0±0.3, 4.0±0.8 and 1.0±0.1 by qRT-PCR (p = 0.26, 0.60 and 0.09 between assays). The stem cell factor Klf4 was chosen for comparison, based on its expected absence of change in the vasculature at this late time in gestation.

Since our a priori hypothesis was that a difference exists between the strains in expression of at least one of the 116 selected Canq1 genes, a less stringent level of significance than used in genome-wide cDNA array analysis was warranted, ie, 2-way ANOVA with p-value corrected using the Bonferroni inequality for pre-planned comparisons among 2 strains and 3 time-points. Thus for strain differences, 7 genes had corrected p-values less than 0.001 and 15 less than 0.01 (Figure 6, letters above bars). Seven genes also had significant differences over time (Table S3, corrected p<0.05). Table 1 lists 19 of these genes different by strain (“Bonadj strain”; only BC017158 and Fus did not have a corrected p<0.01 by this analysis) and Table S3 lists the remaining 4—Il4ra, Il21r, AC133494.1 and Tgfb1i1—which had corrected p-values less than 0.01. Since our a priori hypothesis was that a strain difference exists in expression of one or more of the 116 Canq1 genes, independent of time, we also conducted t-tests (Tables S4 and S5). Twenty-three genes were significant at p<0.01, and 43 at p<0.05 which is not unexpected given their location in different haplotype blocks.

Discussion

We recently identified Canq1 as a primary locus responsible for variation in extent of the collateral circulation in mice [15]. In the present study we sought to refine this locus and identify candidate genes responsible for collateral variation. Collateral density was reduced by approximately 50% in CxB11 RIL mice in which Canq1 is split between B6 (proximal half) and Bc strains. This suggests that Canq1 harbors a polymorphism(s) possibly in its proximal half that governs variation in collateral extent. That a greater reduction was not obtained may reflect mosaicism elsewhere in the CxB11 genome (∼60% Bc), including at three other QTL that we found on Chr 1, 3 and 8 with small effects (Canq-2,-3,-4, LODs of 5–13) [15]. Since multiple regulatory loci can be linked in cis (as well as trans), it is also possible that a variant in each half of Canq1 could be involved—a possibility supported by the cluster of significant SNPs mapped to the far 3′ of Canq1 (Figure 3, Figures S3, S4, S5, S6, S7). Generation of congenic strains that partition Canq1 may allow differentiation between these possibilities.

We previously used association mapping in 15 classical inbred strains and narrowed Canq1 to 170 and 290 kb regions (EMMA-A and-B regions) [15]. To test the robustness of the EMMA-A region for collateral variation and possibly narrow it further, we generated a SNP heatmap for 74 inbred strains and identified the 6 most informative additional inbred strains—3 classical and 3 wild-derived. Association mapping of this 21-strain panel narrowed EMMA-A and increased its statistical significance. While 4 of the 6 new strains had collateral numbers predicted by their haplotype structure, Cast/Ei and PWD were outliers (Figure 2). The unique haplotype structure of these wild-derived strains has discouraged their use in previous mapping studies [35], [36], a finding which our results confirm. However, the EMMA haplotype of the wild-derived LEWES strain fit the predicted collateral number. What might explain this conundrum? Several studies have utilized dense-SNP data from recent re-sequencing efforts (NIEHS and Perlegen) to infer ancestral haplotype origins among the classical inbred strains [35], [36]. Using WSB, PWD and CAST/Ei as reference strains for Mus Musculus subspecies domesticus, musculus and castaneus, together with the hidden Markov Model algorithm, Frazer and colleagues [35] found that 11 classical inbred strains shared 68% haplotype origins with domesticus (WSB), 6% with musculus (PWD), and 3% with castaneus (CAST/Ei). In another study, Yang et al [36] found that wild-derived strains, which are presumed to represent different subspecies, have substantial inter-subspecific introgression. Using the 72% of the autosomal and X-chromosomal 100 kb genomic intervals, for which the ancestry of the reference strains is unambiguous, they estimated that the 11 classical inbred strains inherited 92% of their genomes from Mus domesticus origin, 3–12% from musculus origin and 1–2% from castaneus origin. In a recent study, Kirby and co-workers [37] densely genotyped 121,000 SNPs for 94 inbred strains. Inspection of these data shows that LEWES has close ancestral origins with the WSB strain. Based on the above studies, we postulate that CAST/Ei and PWD are outliers in our study because they share minimal ancestral haplotype origins with the classical inbred strains, while LEWES shares major ancestry origin with the classical inbred strains and the predicted collateral number. Importantly, regardless of whether the wild-derived strains were included or excluded in our association mapping, the same significant region was obtained with similar p-values (Figures S3, S4, S5). Moreover, the diverse genetic background used in our mapping was corrected by applying the kinship matrix. For example, the average identical-by-descent between CAST/Ei and the other 20 stains is 0.45 m, and it is 0.82 between B6 and the other 20 strains. In addition to the above, a significant additional finding from the 21-strain analysis is that it suggests that Canq1 is not only important in controlling collateral formation in the B6 and Bc strains, but also in 19 additional strains and thus in the mouse species itself.

The SJL strain, which has high collateral density yet possesses an EMMA haplotype structure apparently identical to SWR, is also outlier (Figures 2 and 4). Besides the known SNPs that are identical in EMMA-A, ∼400 SNPs imputed with high confidence (>0.9) are identical between SWR and SJL, and the remaining are also the same among the ∼1000 SNPs imputed with lower confidence. What genetic component(s) regulates the variation in native collateral extent between SWR and SJL if no variation exists within EMMA-B? To identify possible additional QTL, plus confirm our previous [15] and current mapping results, we performed genome-wide linkage analysis on a SWRxSJL-F2 cross. No QTL on chromosome 7 was present, a finding congruent with the common haplotype-like block for these strains. These results also strengthen our previous confirmation of Canq1 using association mapping and chromosome substitution strain analysis [15], and the finding by others [16] of a QTL for cerebral infarct volume (Civq1) at the same location as Canq1, using an SWRxB6-F2 cross. Our finding of no other QTL could reflect differences in size of the F2 population and/or fold-differences in trait (collateral number) in our SWRxSJL-F2 cross (n = 123 and 6-fold) versus our previous B6xBc-F2 [15] cross (n = 221 and 30-fold). It could also reflect the presence of additional smaller-effect loci, which is supported by the distribution of the collateral number trait (lower panel of Figure 4).

It is noteworthy that A/J, with its low collateral number (and diameter, Figure S2), also has some outlier-like haplotype features (Figure 2). Yet, collateral number and diameter “follow” chromosome 7 by ∼70% using B6→A/J chromosome substitution strain (CSS) analysis [15]. And 7 of the EMMA-B genes do not fit the CSS analysis “in a simple world”, eg, Gtf3c1 is indistinguishable between A/J and B6 except for 1 SNP, whereas A/J and Bc differ by 166 SNPs (JAX SNP Browser). This would seem to eliminate Gtf3c1 as a candidate gene, a finding supported by its lack of differential expression by even t-test analysis (Table S5). However, compared to the other 20 strains across EMMA-B, A/J appears as a mix. Some genes are identical to B6 while others are identical to Bc, in contrast to the impression from looking at the haplotypes in Figure 2. These considerations emphasize the likelihood that other known (Canq2-4 [15]) and unknown loci besides Canq1 are involved.

The most significant EMMA-A region (132.502–132.504 Mb) lacks mRNA annotation (http://uswest.ensembl.org/Mus_musculus/Location/View?r=7:132495610-132513000). This was confirmed using the UCSC genome browser database. Mammalian transcription factor binding elements are also lacking (Transcription Element Search System, TESS, http://www.cbil.upenn.edu/cgi-bin/tess/tess?RQ=WELCOME). EMMA-A and EMMA-B (132.495–132.513 Mb) also lack annotated microRNAs and other nc(non-coding)RNAs (http://www.ncrna.org/). However, 10 genes are annotated in EMMA-B (discussed below), as well as hundreds of expressed sequence tags (ESTs).

Since large-effects QTL like Canq1 are usually accompanied by changes in expression of the responsible polymorphic gene in the QTL and/or genes within its effector pathway that are located elsewhere in the genome, transcript analysis is a critical tool used to identify candidate genes. We thus measured expression of all 10 of the annotated genes within EMMA-B and 106 genes in the 95% CI of Canq1 having SNP differences in their coding or regulatory (±2 kb) sequence. RNA was obtained from the pia mater of B6 and Bc embryos at E14.5, E16.5 and E18.5. Although the pia mater is an approximately 5 µm thick collagen membrane containing dispersed fibroblasts and IB4 lectin-staining hematopoietic-like cells, these are greatly outnumbered by the endothelial cells that compose the arterial trees, pial capillary plexus, and the collateral circulation that forms during this interval [11], [12]. To our knowledge none of the genes in EMMA-B or those in the wider 95% CI of Canq1 is known to be involved in angiogenesis. Thus, one or more of the differentially (or not, see below) expressed genes may be a novel “collaterogenesis” gene that controls, in trans, expression of a gene(s) located elsewhere in the genome that has been shown to alter collateral formation, eg, Clic4 (Chr4) [18], Vegfa [12], [17] (Chr17), Flk1 [12] (Chr5), Adam10 [12] (Chr9) and Adam17 [12] (Chr12).

Nsmce1, Tbx6, Ino80e, Pycard and 3 “Riken genes” within the 95% CI of Canq1 and one located elsewhere (Tert, telomerase) were differentially expressed greater than 2-fold at all 3 embryonic time-points at the highest level of significance (p<0.05÷150) (Ino80e just missed this level) (Figure 6, Table 1). The EMMA-B gene Nsmce1 (non-structural maintenance of chromosomes (Smc) element-1; Nse1) was 5-fold greater in Bc than B6 (2nd largest fold-difference among the 150 transcripts assayed). Nsmce1 is part of a multi-protein complex important in telomere maintenance during proliferation, compensation for telomerase deficiency, inhibition of apoptosis, and promotion of cell survival [38]–[42]. These functions may be important in collaterogenesis.

Tbx6 (T-box-6 transcription factor) is required for mesoderm, somite and left-right body axis specification that involves Wnt/β-catenin and BMP/TGFβ1→Notch/Delta signaling [43], [44]. Cross-talk exists among the Tbox, Wnt/β-catenin, TGFβ1, VEGF and Notch pathways [45]–[47]. Although no information is available regarding interaction between Tbx6 and Vegfa, this is well-established for Tbx1 [48] and less-so with Tbx2 [49]. Evidence that VEGF-A/Flk1→Delta/Notch drives collateral formation [12], together with the above findings, identify Tbx6 as a candidate.

Ino80e (regulator of inositol responsive gene expression; Ccdc95) in human is one of the 16 subunits of the INO80 chromatin remodeling complex. INO80 controls transcription of genes that regulate cell proliferation, differentiation and embryonic development, as well as DNA replication, repair and telomerase activity [50], [51]. Thus Ino80e, Nsmce1 and Jmjd5 (below) are attractive epigenetic candidates capable of regulating multiple genes.

Pycard (apoptosis speck-like protein containing a C-terminal caspase recruitment domain; ASC) was the most strongly downregulated gene in Bc with the lowest p-value (0.00004) among the 127 Canq1 transcripts examined (Table 1). Pycard is an adaptor protein for NLRP3 (nucleotide binding leucine rich repeats-containing protein 3) that is increased by cell-stress stimuli and required for formation of the multi-protein inflammasome complex, which is induced in activated macrophages and causes interleukin secretion, additional macrophage recruitment, and caspase-1-mediated apoptosis [52]–[54].

The Riken ESTs D430042O09Rik, 9130019O22Rik and B230325K18Rik may be ESTs for long-ncRNA “genes” [55]–[57]. Although little annotation is available for this relatively new family of RNA genes, databases www.biogps.org and www.nextbio.com/bodyatlas show the following: D430042O09Rik is ubiquitously expressed and greater in Bc that B6 tissues, and has conserved homology through C elegans; 9130019O22Rik is ubiquitously expressed at comparable levels in both strains; B230325K18Rik is comparable in Bc and B6. If these loci function as lncRNAs they could regulate one or multiple genes involved in collateral formation and maintenance.

Jmjd5, located just 3′ to EMMA-B, was not differentially expressed. However, a loss-of-function or gain-of-function variant in a gene could be important yet not be accompanied by a change in expression. Jmjd5 (jumongi domain-containing protein 5; lysine-specific demethylase 8) is a newly discovered member of the jumongi-C domain-containing proteins that are receiving considerably attention [58]–[60]. Some JmjC proteins are histone demethylases involved in epigenetic regulation. Although nothing is known about mouse Jmjd5 function, human JMJD5 (aka KDM8) is a H3 lysine36 demethylase and transcriptional activator of cyclin A1 that is required for cell cycle progression and is a potential tumor suppressor. Given the rapidly expanding roles for histone demethylases in controlling coordinate expression of multiple genes within a pathway, Jmjd5 is a candidate gene.

In our previous study [15] we examined all genes in the 95% confidence interval of Canq1 using Ingenuity Pathway Enrichment Analysis. Thirteen of 20 known pathways showed significance (p<0.05, Benjamini-Hochberg), with cell-cell signaling and immune response pathways showing the greatest enrichment. However, no additional referenced gene connections were identified beyond those discussed above.

We also measured expression of 13 genes that control angiogenesis and 10 involved in endothelial cell proliferation that reside outside of Canq1. Only Tert (a protein component of telomere reverse transcriptase (telomerase)) was significantly differentially expressed. Increased expression of this chromosome-stabilizing, anti-aging/cell-survival protein [61] in Bc mice may be part of a compensatory pathway activated by deficiencies in an above-mentioned gene(s) that are predisposing to failure to form or loss of nascent collaterals during embryogenesis. Telomere-independent functions have also been recently identified for telormerase [62]. Telomerase is a cofactor in the β-catenin transcriptional complex, facilitating canonical Wnt signaling in vitro and in vivo. Its RNA polymerase activity may amplify certain ncRNAs, including promoting the generation of siRNAs. Moreover, increased expression of telomerase sensitizes mitochondrial DNA to oxidative damage and stimulates apoptosis. Thus, a polymorphism in Canq1 may, secondarily or in trans, increase expression of telomerase in pial vessels of Bc embryos and contribute to reduced collateral formation and increased pruning. It is also intriguing that Nsmce1 and Ino80e interact with telomerase (discussed above), and that TGFβ1 and VEGF/Notch signaling are known to have significant cross talk with Wnt/β-catenin signaling [46].

Previously annotated mouse QTL identified within Canq1 (128.3–142.2, MGI Mouse Genome Browser, Build 37) are unrelated to the collateral phenotype: Alcp12 (alcohol preference,B6xA/J); coronin (actin binding protein-1A, B6xBXSB), lupus susceptibility (BXSB); Myo1 (myocardial infarction susceptibility, BXSBxNZW, 142.2-extreme 3′ of Canq1); Mob1, (multigenic obesity, SpretxBc), Rthyd1 (resistant to thymic deletion-1); Scc12 (susceptibility to colon cancer 12); Sluc19 (susceptibility to lung cancer-19); Vpantd (valproic acid-induced neural tube defect); Dice2 (determination of IL4 commitment-2, B6xBc); Il4ppq (IL4 producing potential QTL, B6xBXSB, NZBxNZW, presumed same as Dice2); Tsiq1 (T cell secretion of IL4-1m, presumed same as Dice2). Regarding the latter 3 QTL, Bc mice have ∼50-fold increased levels of IL4 compared to other strains, associated with a loss-of-function mutation which may explain their reduced mRNA (Fig. 6; Table S4) if resulting from negative feedback. No QTL or eQTL have been identified within the human genome syntenic to the Canq1 interval, including in the 8 Mb flanking region (16p12.3-11.2/10q25-26.3) for the following traits: collateral circulation, stroke, ischemic stroke, cerebral circulation, coronary artery disease, angina, coronary ischemia, coronary circulation, coronary blood flow, myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease, intermittent claudication (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim; www.genome.gov/gwastudies/). The UCSC database identifies mir-762 at 134.85 and mir-1962 at the extreme 3′ position (142.8 Mb) of Canq1. In-situ hybridization of mir-762 was insufficient to permit structural assignment in the E14.5 mouse transcriptone atlas (http://www.eurexpress.org). The http://www.mirbase.org/ database lists only 3 deep-sequencing reads for miR-762 (1 in testes, 2 in brain). Since a miRNA of vascular importance would be expected to be reasonably expressed in most if not all tissues, these reports of very low expression in highly restricted tissue cDNAs, compared to other miRNAs, argue against the importance of mir-762 in Canq1.

Conclusions based on analysis of knockout mice and gene expression have limitations, including compensations from global deletion, difficulty in distinguishing gain-of-function variants, and altered expression dependent on changes elsewhere in the genome. In this regard, expression of Flk1 and Clic4 were not different in Bc and B6 embryos (Tables S3, S4, S5) despite their involvement in collateral formation based on targeted disruption [12], [17], [18].

In summary, the present results significantly narrow and prioritize the large number of candidate genes previously reported for the co-localized QTL Canq1 [15] Civq1 [16] and HSq1 [19]. Additional studies sequencing EMMA-B and the wider Canq1 interval in several strains with high and low collateral extent, generation of congenic strains partitioning EMMA and Canq1, and other approaches to investigate the above candidate genes, will be needed to identify the basis for this important locus for genetic-dependent variation in the collateral circulation.

Supporting Information

Pial collateral number per hemisphere and average diameter for 21 inbred strains, including 15 strains reported previously [9] . Green bar denotes 6 newly phenotyped strains. Number of animals given at the base of each column.

(PDF)

Heatmap of known and imputed SNPs within the EMMA region for 74 strains. Abscissa, physical locations of selected SNPs across the EMMA region (p = 2.2×10−5). Ordinate, 74 inbred strains. 15 strains at bottom (bracket) arranged from least-to-most collateral number, per Zhang et al. [9]. Each vertical line represents a SNP (blue, SNP same as B6; green, different from B6; blank, genotype unknown).

(PDF)

EMMA mapping using 20 strains excluding Cast/Ei. Red and blue dots, the most significant and the second most significant SNPs in the previous EMMA mapping [15]. Same color scheme in Figures S3, S4, S5, S6, S7. Mapping allowed fewer than 3 SNPs with missing genotypes.

(PDF)

EMMA mapping using 19 strains excluding Cast/Ei and PWD. Mapping allowed fewer than 3 SNPs with missing genotypes.

(PDF)

EMMA mapping using 18 strains excluding Cast/Ei, PWD, and LEWES. Mapping allowed fewer than 3 SNPs with missing genotypes.

(PDF)

EMMA mapping using 21 strains. Mapping allowed no SNPs with missing genotypes.

(PDF)

EMMA mapping using 21 strains with only informative SNPs. Mapping allowed fewer than 3 SNPs with missing genotypes.

(PDF)

IL-4 and Itgal knockout mice show no differences in perfusion, compared to their background strain, immediately after unilateral femoral artery ligation (FAL), indicating as in the pial circulation no effect on native collateral extent in skeletal muscle. See Chalothorn and Faber [11] for Materials and Methods. IL-4, but not Itgal knockout mice, show deficits in recovery of perfusion and greater tissue ischemia and use-impairment with days after FAL. These deficiencies suggest impaired collateral remodeling, although lesser potential contributions could include less ischemic capillary angiogenesis and/or less reduction in resistance (smooth muscle tone or anatomic outward remodeling) upstream of, downstream of, or within the recruited hindlimb collateral network.

(PDF)

Primers for qRT-PCR.

(PDF)

Differential blood count analysis in IL-4 and Itgal knockout mice, and C57BL/6 background strain. Itgal knockouts show significant increases in cell counts for white blood cells, lymphocytes, granulocytes and monocytes, while platelet count is lower. *,**,*** p<0.05, 0.01, 0.001. Dunne et al and Ding et al reported similar increases in the above blood cell types in Itgal deficient mice, eg 3-fold for total leukocytes, 4-fold for PMNs, and 2.5-fold for mononuclear cells, but did not report platelets. Regarding the decrease in platelets, we have been unable to find any previous report that circulating platelet number is decreased in Itgal−/− mice. However, Armugam et al reported that platelet adhesion to cerebral venules after MCA occlusion and reperfusion is 50% less in LFA−/− mice. Emoto et al found that platelets were reduced in livers following low dose LPS challenge in LFA−/− mice. Dunne JL, Collins RG, Beaudet AL, Ballantyne CM, Ley K. Mac-1, but not LFA-1, uses intercellular adhesion molecule-1 to mediate slow leukocyte rolling in TNF-alpha-induced inflammation. J Immunol. 2003;171:6105–11. Ding ZM, Ballantyne CM et al. Relative Contribution of LFA-1 and Mac-1 to Neutrophil Adhesion and Migration. J Immunol, 1999;163:5029–5038. Arumugam TV, Granger DN, et al. Contributions of LFA-1 and Mac-1 to brain injury and microvascular dysfunction induced by transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. AJP-Heart & Lung, 2004;287: H2555–H2560. Emoto M, Kaufmann SHE et al. Increased Resistance of LFA-1-Deficient Mice to Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Shock/Liver Injury in the Presence of TNF-α and IL-12 Is Mediated by IL-10: A Novel Role for LFA-1 in the Regulation of the Proinflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokine Balance. J Immunol. 2003;171:584–593.

(PDF)

ANOVA analysis of expression for 150 genes. Expression assay by NanoString nCounter. 3 RNA samples of pia at each time point for each strain, with each sample composing of ≥8 embryos from ≥2 litters (18 samples, ∼200 embryos). Transcript number for each gene normalized to mean transcript number for 6 housekeeping genes: βactin, Gapdh, Tubb5, Hprt1, Ppia, Tbp. * Gene number same as in Figure 6 and Table 1. †I, genes in EMMA region; II, genes in 95% CI of Chr 7 QTL; III, angiogenic-related genes located elsewhere in genome; IV, proliferation-related genes located elsewhere in genome. ‡Fold change for Bc vs B6 if positive and B6 vs Bc if negative. §Bonferroni-adjusted p values (p-value÷150, for 150 genes/splice forms assayed) from 2-way ANOVA for 2 strains (20 genes p<0.05) and 3 embryonic days (6 genes p<0.05).

(PDF)

Genes having differential expression between strains by t-test analysis. Expression assay by NanoString nCounter. 3 RNA samples of pia at each time point for each strain, with each sample composing of ≥8 embryos from ≥2 litters (18 samples, ∼200 embryos). Transcript number for each gene normalized to mean transcript number for 6 housekeeping genes: βactin, Gapdh, Tubb5, Hprt1, Ppia, Tbp. Gene number same as in Figure 6 and Table 1. †I, genes within the EMMA region; II, gene s in 95% CI of Chr 7 QTL; III, angiogenesis-related genes located elsewhere in genome; IV, proliferation-related genes located elsewhere in genome. ‡Fold change for BALB/c vs B6 if positive and B6 vs BALB/c if negative. §Bonferroni-adjusted p-values (p-value÷ 50) from t-tests independent of embryonic days (1 gene <0.05). ∥p values from t tests independent of embryonic days, without Bonferroni adjustment (49 genes <0.05).

(PDF)

T test analysis of expression for 150 genes. Expression assay by NanoString nCounter. 3 RNA samples of pia at each time point for each strain, with each sample composing of ≥8 embryos from ≥2 litters (18 samples, ∼200 embryos). Transcript number for each gene normalized to mean transcript number for 6 housekeeping genes: βactin, Gapdh, Tubb5, Hprt1, Ppia, Tbp. • Gene number same as in Figure 6 and Table 1. † I, genes within the EMMA region; II, gene s in 95% CI of Chr 7 QTL; III, angiogenesis-related genes located elsewhere in genome; IV, proliferation-related genes located elsewhere in genome. ‡ Fold change for BALB/c vs B6 if positive and B6 vs BALB/c if negative. § Bonferroni-adjusted p-values (p-value÷ 50) from t-tests independent of embryonic days (1 gene <0.05). ∥ p values from t tests independent of embryonic days, without Bonferroni adjustment (49 genes <0.05).

(PDF)

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Daniel Pomp (UNC Genetics) and Fei Zou (UNC Biostatistics) for helpful discussion.

Supplementary material is available at the PLoS ONE website.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: Funding support for this work was received from the National Institutes of Health, Heart Lung and Blood Institute, grants HL062584 and HL090655 (to JEF). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Faber JE, Dai X, Lucitti J. Genetic and environmental mechanisms controlling formation and maintenance of the native collateral circulation. In: Deindl E, Schaper W, editors. Arteriogenesis – Molecular Regulation, Pathophysiology and Therapeutics. Aachen: Shaker Verlag. Chapter 1; 2011. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brozici M, van der Zwan A, Hillen B. Anatomy and functionality of leptomeningeal anastomoses: A review. Stroke. 2003;34:2750–2762. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000095791.85737.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shuaib A, Butcher K, Mohammad AA, Saqqur M, Liebeskind DS. Collateral blood vessels in acute ischaemic stroke: a potential therapeutic target. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:909–21. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Marchi SF, Gloekler S, Meier P, Traupe T, Steck H, et al. Determinants of preformed collateral vessels in the human heart without coronary artery disease. Cardiology. 2011;118:198–206. doi: 10.1159/000328648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaper W. Collateral circulation: Past and present. Basic Research in Cardiology. 2009;104:5–21. doi: 10.1007/s00395-008-0760-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meier P, Gloekler S, Zbinden R, Beckh S, de Marchi SF, et al. Beneficial effect of recruitable collaterals: A 10-year follow-up study in patients with stable coronary artery disease undergoing quantitative collateral measurements. Circulation. 2007;116:975–983. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.703959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menon BK, Smith EE, Modi J, Patel SK, Bhatia R, et al. Regional leptomeningeal score on CT angiography predicts clinical and imaging outcomes in patients with acute anterior circulation occlusions. Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32:1640–5. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chalothorn D, Clayton JA, Zhang H, Pomp D, Faber JE. Collateral density, remodeling, and vegf-a expression differ widely between mouse strains. Physiol Genomics. 2007;30:179–191. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00047.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H, Prabhakar P, Sealock R, Faber JE. Wide genetic variation in the native pial collateral circulation is a major determinant of variation in severity of stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:923–934. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalothorn D, Faber JE. Strain-dependent variation in collateral circulatory function in mouse hindlimb. Physiol Genomics. 2010;42:469–479. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00070.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chalothorn D, Faber JE. Formation and maturation of the native cerebral collateral circulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucitti JL, Mackey J, Morrison J, Haigh J, Adams R, et al. Formation of the collateral circulation is regulated by vascular endothelial growth factor-A and a disintegrin and metalloprotease family members 10 and 17. Circ Res. 2012 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.279109. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dai X, Faber JE. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase deficiency causes collateral vessel rarefaction and impairs activation of a cell cycle gene network during arteriogenesis. Circ Res. 2010;106:1870–1881. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.212746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faber JE, Zhang H, Prabhakar, Lassance-Soares RM, Burnett MS, et al. Aging causes collateral rarefaction and increased severity of ischemic injury in multiple tissues. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1748–56. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.227314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S, Zhang H, Dai X, Sealock R, Faber JE. Genetic architecture underlying variation in extent and remodeling of the collateral circulation. Circ Res. 2010;107:558–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.224634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keum S, Marchuk DA. A locus mapping to mouse chromosome 7 determines infarct volume in a mouse model of ischemic stroke Circ. Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:591–598. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.883231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clayton JA, Chalothorn D, Faber JE. Vascular endothelial growth factor-A specifies formation of native collaterals and regulates collateral growth in ischemia. Circ Res. 2008;103:1027–1036. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.181115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chalothorn D, Zhang H, Smith JE, Edwards JC, Faber JE. Chloride intracellular channel-4 is a determinant of native collateral formation in skeletal muscle and brain. Circ Res. 2009;105:89–98. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.197145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ayotunde OD, Keum S, Hazarika S, Youngun L, Lamonte GM, et al. A QTL (LSq-1) on mouse chromosome 7 is linked to the absence of tissue loss following surgical hind-limb ischemia. Circulation. 2008;117:1207–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.736447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang HM, Zaitlen NA, Wade CM, Kirby A, Heckerman D, et al. Efficient control of population structure in model organism association mapping. Genetics. 2008;178:1709–1723. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.080101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manichaikul A, Moon JY, Sen S, Yandell BS, Broman KW. A model selection approach for the identification of quantitative trait loci in experimental crosses, allowing epistasis. Genetics. 2009;181:1077–1086. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.094565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynch M, Ritland K. Estimation of pairwise relatedness with molecular markers. Genetics. 1999;152:1753–1766. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoover-Plow J, Shchurin A, Hart E, Sha J, Hill AE, et al. Genetic background determines response to hemostasis and thrombosis. BMC Blood Disord. 2006;6:6–18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2326-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geiss GK, Bumgarner RE, Birditt B, Dahl T, Dowidar N, et al. Direct multiplexed measurement of gene expression with color-coded probe pairs. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:317–325. doi: 10.1038/nbt1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malkov VA, Serikawa KA, Balantac N, Watters J, Geiss G, et al. Multiplexed measurements of gene signatures in different analytes using the nanostring ncounter assay system. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:80–89. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L. Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1–10. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shifman S, Bell JT, Copley RR, Taylor MS, Williams RW, et al. Mott R, Flint J. A high-resolution single nucleotide polymorphism genetic map of the mouse genome. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faffe DS, Flynt L, Bourgeois K, Panettieri RA, Jr, Shore SA. Interleukin-13 and interleukin-4 induce vascular endothelial growth factor release from airway smooth muscle cells: Role of vascular endothelial growth factor genotype. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:213–218. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0147OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamaji-Kegan K, Su Q, Angelini DJ, Johns RA. Il-4 is proangiogenic in the lung under hypoxic conditions. J Immunol. 2009;182:5469–5476. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0713347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paul WE, Zhu J. How are t(h)2-type immune responses initiated and amplified? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:225–235. doi: 10.1038/nri2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mace EM, Monkley SJ, Critchley DR, Takei F. A dual role for talin in NK cell cytotoxicity: Activation of lfa-1-mediated cell adhesion and polarization of NK cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:948–956. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arumugam TV, Salter JW, Chidlow JH, Ballantyne CM, Kevil CG, et al. Contributions of lfa-1 and mac-1 to brain injury and microvascular dysfunction induced by transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H2555–2560. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00588.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carmichael ST. Rodent models of focal stroke: Size, mechanism, and purpose. NeuroRx. 2005;2:396–409. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.3.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohr JP. Stroke: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frazer KA, Eskin E, Kang HM, Bogue MA, Hinds DA, et al. A sequence-based variation map of 8.27 million snps in inbred mouse strains. Nature. 2007;448:1050–1053. doi: 10.1038/nature06067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang H, Bell TA, Churchill GA, Pardo-Manuel de Villena F. On the subspecific origin of the laboratory mouse. Nature genetics. 2007;39:1100–1107. doi: 10.1038/ng2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirby A, Kang HM, Wade CM, Cotsapas C, Kostem E, et al. Fine mapping in 94 inbred mouse strains using a high-density haplotype resource. Genetics. 2010;185:1081–1095. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.115014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujioka Y, Kimata Y, Nomaguchi K, Watanabe K, Kohno K. Identification of a novel non-structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) component of the SMC5-SMC6 complex involved in DNA repair. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21585–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201523200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Piccoli G, Torres-Rosell J, Aragón L. The unnamed complex: what do we know about Smc5-Smc6? Chromosome Res. 2009;17:251–63. doi: 10.1007/s10577-008-9016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chavez A, George V, Agrawal V, Johnson FB. Sumoylation and the structural maintenance of chromosomes (Smc) 5/6 complex slow senescence through recombination intermediate resolution. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11922–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu W, Tanasa B, Tyurina OV, Zhou TY, Gassmann R, et al. PHF8 mediates histone H4 lysine 20 demethylation events involved in cell cycle progression. Nature. 2010;466:508–12. doi: 10.1038/nature09272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noël JF, Wellinger RJ. Abrupt telomere losses and reduced end-resection can explain accelerated senescence of Smc5/6 mutants lacking telomerase. DNA Repair (Amst) 2011;10:271–82. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wardle FC, Papaioannou VE. Teasing out T-box targets in early mesoderm. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:418–25. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toyo-oka K, Mori D, Yano Y, Shiota M, Iwao H, et al. Protein phosphatase 4 catalytic subunit regulates Cdk1 activity and microtubule organization via NDEL1 dephosphorylation. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:1133–47. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200705148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghogomu SM, van Venrooy S, Ritthaler M, Wedlich D, Gradl D. HIC-5 is a novel repressor of lymphoid enhancer factor/T-cell factor-driven transcription. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1755–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505869200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dejana E. The role of wnt signaling in physiological and pathological angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2010;107:943–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chuai M, Weijer CJ. Regulation of cell migration during chick gastrulation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:343–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stalmans I, Lambrechts D, De Smet F, Jansen S, Wang J, et al. VEGF: a modifier of the del22q11 (DiGeorge) syndrome? Nat Med. 2003;9:173–82. doi: 10.1038/nm819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wentzel P, Eriksson UJ. Altered gene expression in neural crest cells exposed to ethanol in vitro. Brain Res. 2009;1305(Suppl):S50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen L, Cai Y, Jin J, Florens L, Swanson SK, et al. Subunit organization of the human INO80 chromatin remodeling complex: an evolutionarily conserved core complex catalyzes ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:11283–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.222505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morrison AJ, Shen X. Chromatin remodelling beyond transcription: the INO80 and SWR1 complexes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:373–84. doi: 10.1038/nrm2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davis BK, Wen H, Ting JP. The inflammasome NLRs in immunity, inflammation, and associated diseases. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:707–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Franchi L, Muñoz-Planillo R, Reimer T, Eigenbrod T, Núñez G. Inflammasomes as microbial sensors. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:611–5. doi: 10.1002/eji.200940180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McElvania Tekippe E, Allen IC, Hulseberg PD, Sullivan JT, et al. Granuloma formation and host defense in chronic Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection requires PYCARD/ASC but not NLRP3 or caspase-1. PLoS One. 2010;e12320 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Numata K, Kanai A, Saito R, Kondo S, Adachi J, et al. Identification of putative noncoding RNAs among the RIKEN mouse full-length cDNA collection. Genome Res. 2003;13:1301–6. doi: 10.1101/gr.1011603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Loewer S, Cabili MN, Guttman M, Loh YH, Thomas K, et al. Large intergenic non-coding RNA-RoR modulates reprogramming of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1113–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hung T, Wang Y, Lin MF, Koegel AK, Kotake Y, et al. Extensive and coordinated transcription of noncoding RNAs within cell-cycle promoters. Nat Genet. 2011;43:621–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klose RJ, Kallin EM, Zhang Y. JmjC-domain-containing proteins and histone demethylation. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:715–27. doi: 10.1038/nrg1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hsia DA, Tepper CG, Pochampalli MR, Hsia EY, Izumiya C, et al. KDM8, a H3K36me2 histone demethylase that acts in the cyclin A1 coding region to regulate cancer cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9671–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000401107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shi Y. Histone lysine demethylases: emerging roles in development, physiology and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:829–33. doi: 10.1038/nrg2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Lange T. How telomeres solve the end-protection problem. Science. 2009;326:948–52. doi: 10.1126/science.1170633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martínez P, Blasco MA. Telomeric and extra-telomeric roles for telomerase and the telomere-binding proteins. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:161–76. doi: 10.1038/nrc3025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Pial collateral number per hemisphere and average diameter for 21 inbred strains, including 15 strains reported previously [9] . Green bar denotes 6 newly phenotyped strains. Number of animals given at the base of each column.

(PDF)

Heatmap of known and imputed SNPs within the EMMA region for 74 strains. Abscissa, physical locations of selected SNPs across the EMMA region (p = 2.2×10−5). Ordinate, 74 inbred strains. 15 strains at bottom (bracket) arranged from least-to-most collateral number, per Zhang et al. [9]. Each vertical line represents a SNP (blue, SNP same as B6; green, different from B6; blank, genotype unknown).

(PDF)

EMMA mapping using 20 strains excluding Cast/Ei. Red and blue dots, the most significant and the second most significant SNPs in the previous EMMA mapping [15]. Same color scheme in Figures S3, S4, S5, S6, S7. Mapping allowed fewer than 3 SNPs with missing genotypes.

(PDF)

EMMA mapping using 19 strains excluding Cast/Ei and PWD. Mapping allowed fewer than 3 SNPs with missing genotypes.

(PDF)

EMMA mapping using 18 strains excluding Cast/Ei, PWD, and LEWES. Mapping allowed fewer than 3 SNPs with missing genotypes.

(PDF)

EMMA mapping using 21 strains. Mapping allowed no SNPs with missing genotypes.

(PDF)

EMMA mapping using 21 strains with only informative SNPs. Mapping allowed fewer than 3 SNPs with missing genotypes.

(PDF)

IL-4 and Itgal knockout mice show no differences in perfusion, compared to their background strain, immediately after unilateral femoral artery ligation (FAL), indicating as in the pial circulation no effect on native collateral extent in skeletal muscle. See Chalothorn and Faber [11] for Materials and Methods. IL-4, but not Itgal knockout mice, show deficits in recovery of perfusion and greater tissue ischemia and use-impairment with days after FAL. These deficiencies suggest impaired collateral remodeling, although lesser potential contributions could include less ischemic capillary angiogenesis and/or less reduction in resistance (smooth muscle tone or anatomic outward remodeling) upstream of, downstream of, or within the recruited hindlimb collateral network.

(PDF)

Primers for qRT-PCR.

(PDF)

Differential blood count analysis in IL-4 and Itgal knockout mice, and C57BL/6 background strain. Itgal knockouts show significant increases in cell counts for white blood cells, lymphocytes, granulocytes and monocytes, while platelet count is lower. *,**,*** p<0.05, 0.01, 0.001. Dunne et al and Ding et al reported similar increases in the above blood cell types in Itgal deficient mice, eg 3-fold for total leukocytes, 4-fold for PMNs, and 2.5-fold for mononuclear cells, but did not report platelets. Regarding the decrease in platelets, we have been unable to find any previous report that circulating platelet number is decreased in Itgal−/− mice. However, Armugam et al reported that platelet adhesion to cerebral venules after MCA occlusion and reperfusion is 50% less in LFA−/− mice. Emoto et al found that platelets were reduced in livers following low dose LPS challenge in LFA−/− mice. Dunne JL, Collins RG, Beaudet AL, Ballantyne CM, Ley K. Mac-1, but not LFA-1, uses intercellular adhesion molecule-1 to mediate slow leukocyte rolling in TNF-alpha-induced inflammation. J Immunol. 2003;171:6105–11. Ding ZM, Ballantyne CM et al. Relative Contribution of LFA-1 and Mac-1 to Neutrophil Adhesion and Migration. J Immunol, 1999;163:5029–5038. Arumugam TV, Granger DN, et al. Contributions of LFA-1 and Mac-1 to brain injury and microvascular dysfunction induced by transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. AJP-Heart & Lung, 2004;287: H2555–H2560. Emoto M, Kaufmann SHE et al. Increased Resistance of LFA-1-Deficient Mice to Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Shock/Liver Injury in the Presence of TNF-α and IL-12 Is Mediated by IL-10: A Novel Role for LFA-1 in the Regulation of the Proinflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokine Balance. J Immunol. 2003;171:584–593.

(PDF)