Abstract

Objective

To examine how genes and environments contribute to relationships among Trail Making test conditions and the extent to which these conditions have unique genetic and environmental influences.

Method

Participants included 1237 middle-aged male twins from the Vietnam-Era Twin Study of Aging (VESTA). The Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System Trail Making test included visual searching, number and letter sequencing, and set-shifting components.

Results

Phenotypic correlations among Trails conditions ranged from 0.29 – 0.60, and genes accounted for the majority (58–84%) of each correlation. Overall heritability ranged from 0.34 to 0.62 across conditions. Phenotypic factor analysis suggested a single factor. In contrast, genetic models revealed a single common genetic factor but also unique genetic influences separate from the common factor. Genetic variance (i.e., heritability) of number and letter sequencing was completely explained by the common genetic factor while unique genetic influences separate from the common factor accounted for 57% and 21% of the heritabilities of visual search and set-shifting, respectively. After accounting for general cognitive ability, unique genetic influences accounted for 64% and 31% of those heritabilities.

Conclusions

A common genetic factor, most likely representing a combination of speed and sequencing accounted for most of the correlation among Trails 1–4. Distinct genetic factors, however, accounted for a portion of variance in visual scanning and set-shifting. Thus, although traditional phenotypic shared variance analysis techniques suggest only one general factor underlying different neuropsychological functions in non-patient populations, examining the genetic underpinnings of cognitive processes with twin analysis can uncover more complex etiological processes.

Keywords: executive function, genetics, heritability, twins, middle-age, speed, trail making

Introduction

The Trail Making Test (TMT) is one of the most widely used neuropsychological tests, providing assessments of visual-motor scanning, processing speed, and executive function (Lezak, 2004). Originally part of the Army Individual Tests Battery (1944), the TMT was later incorporated into the Halstead-Reitan Test Battery (Reitan & Wolfson, 1985) and is now a part of several neuropsychological batteries (Lezak, 2004). The traditional TMT consists of two parts: Trails A, which is primarily a measure of processing speed; and Trails B, which is generally used as an index of executive function.

Delis, Kaplan, and Kramer (Delis, Kaplan, & Kramer, 2001) developed an expanded version of the TMT that includes five conditions: Trails 1 (visual search), Trails 2 (number sequencing), Trails 3 (letter sequencing), Trails 4 (number-letter switching, set shifting) and Trails 5 (motor speed). Trails 2 and Trails 4 directly correspond to Trails A and Trails B from the traditional TMT. Trails 2 (number sequencing) and 3 (letter sequencing) are commonly used as measures of processing speed while Trails 4 (set shifting) is considered an index of executive function. The traditional TMT does not specifically isolate certain cognitive component processes that may contribute to performance on the task, particularly on the set-shifting task (Trails B). For instance, poor performance on the switching activity could be due to visual search and motor control deficits. Likewise, letter sequencing could also contribute to performance on the number-letter switching condition. The Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Trail Making test specifically isolates these processes in its five testing conditions (Delis, et al., 2001).

Performance on the TMT is associated with several neuropsychological disorders and processes. The TMT is one of the most widely used assessments for brain damage, particularly damage to the frontal lobe. For example, performance on D-KEFS Trails 3, Trails 4 and Trails 5 conditions has been shown to be impaired in patients with frontal lobe damage (Yochim, Baldo, Nelson, & Delis, 2007). The TMT is also a useful tool is assessing age-related cognitive deficits. Both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have shown age-related declines in TMT performance. Rasmusson, Zonderman, Kawas and Resnick (1998) demonstrated that, in a sample of 60–96 year olds, age significantly predicted decline in both Trails A and B. Additionally, this study demonstrated that within-person declines (over a 2-year period) were steepest in the oldest age group (90–96 years). Giovagnoli et al. (1996) found similar results in a broader aged sample of 20–70 year olds. TMT performance has further been shown to be sensitive to dementia (Rasmusson, et al., 1998). Impaired TMT performance has also been linked to conditions such as schizophrenia and post-traumatic stress disorder (Beckham, Crawford, & Feldman, 1998; Sponheim et al., 2009).

Determining whether various conditions of the TMT reflect distinct cognitive processes is of great relevance to neuropsychologists. Despite being one of the most widely used neuropsychological tests, there is still debate over whether the conditions of the TMT measure discrete cognitive functions, in particular whether set-shifting ability is distinct from other processes such as visual search, processing speed, sequencing ability, and motor speed (Bowie & Harvey, 2006). Even though the set-shifting component of the TMT is considered a measure of executive function, it also involves a substantial processing speed component; in fact, the traditional Trails A and Trails B have been shown to be highly correlated (e.g., r = 0.66) (Corrigan & Hinkeldey, 1987).

Furthermore, studies utilizing phenotypic factor analysis have suggested that executive function is not a distinct cognitive process from processing speed (Salthouse, 2005; Salthouse, Atkinson, & Berish, 2003). These findings are consistent with a cogent argument made by Delis, Jacobson, Bondi, Hamilton and Salmon (2003) regarding the pitfalls of shared variance techniques such as factor analysis in the assessment of cognition. Specifically, Delis et al. (2003) state that “cognitive measures that share variance in the intact brain––thereby giving the facade of assessing a unitary construct––can dissociate and contribute to unique variance in the damaged brain, but only if the pathology occurs in brain regions known to disrupt vital cognitive processes tapped by those measures” (p. 936).

Univariate genetic analyses have shown that both Trails A and B are moderately heritable, with reported heritability (h2) estimates (proportion of variance due to genetic factors) of 0.23–0.38 for Trails A to 0.43–0.65 for Trails B (Buyske et al., 2006; Pardo et al., 2006; Swan & Carmelli, 2002). Although these studies indicate that genetic factors influence both the traditional Trails A and B conditions, these univariate analyses are entirely uninformative about genetic influences on the relationship between TMT conditions. In addition, while the D-KEFS TMT breaks the test up into even more component processes, to our knowledge there have been no prior studies reporting heritabilities of the various D-KEFS TMT conditions, nor have there been multivariate phenotypic or genetic studies of the D-KEFS Trails that have specifically examined covariance across conditions.

Multivariate genetic studies (e.g., twin studies) of cognition have supported the idea that a common genetic factor largely contributes to the relationships among cognitive measures (Petrill et al., 1998; Alarcon et al., 1998; Bouchard and McGue, 2003; Johnson et al., 2004). Across many studies, a common genetic factor (g) was found to account for the similarity among differing measures of cognition, while measure-specific environmental influences contribute to the differences among measures. However, Johnson et al., (2004) cautions that there is still a substantial amount of variation in individual cognitive measures that is not explained by ‘g,’ Petrill et al. (1997) also noted that it is important to understand both common genetic influences that contribute to overall cognitive ability as well as specific genetic (separate from ‘g’) and environmental influences on individual cognitive measures, because these specific influences “split cognitive ability into different cognitive dimensions” (pg. 99).

Along these lines, studies utilizing multivariate behavioral genetic analysis have found that executive functions can be separated from other cognitive functions via underlying genetic architecture in non-patient samples. For example, in their sample of twins ages 16–20 years, Friedman et al. (Friedman et al., 2008) found that the executive functions of inhibiting, updating, and shifting had some distinct genetic influences that were separate from processing speed. In a sample of middle-aged male twins, Kremen et al. (Kremen et al., 2007) showed that the executive (current processing) component of reading span had distinct genetic influences that could be separated from reading ability and span capacity components. Furthermore, twin studies show that the genetic factors underlying relationships among a set of cognitive measures do not necessarily correspond to the factors observed at the phenotypic level. In the study by Friedman et al. (2008), while there were three phenotypic factors (updating, inhibiting, and shifting) that accounted for the variance of executive function, only one common genetic factor was estimated in the genetic analysis.

In a study of the Tower of London Test, Kremen et al. ((Kremen et al.), found evidence for a single phenotypic factor underlying performance on the Tower of London test, but there were two genetic factors (speed and accuracy), in their sample of middle-aged male twins. On the other hand, not all measures of executive function have been found to be heritable. For example, Kremen et al. (2007) found that in the same sample in which the Tower of London was heritable, the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) was not heritable. The finding of little or no heritability has been replicated in almost all twin studies of the WCST, including those with child and adolescents and younger adults (Kremen et al., 2007; Kremen and Lyons, 2011).

Differences across studies may be a function of the different measures that were included or the different age cohorts that were studied, given that executive functions may be particularly susceptible to aging effects (De Luca et al., 2003). Regardless, to the best of our knowledge, no study has utilized multivariate behavioral genetic analysis to examine the TMT, specifically to determine whether the set-shifting (executive function) condition of the TMT has distinct genetic influences from the other Trails conditions.

There is also extensive literature on the relationship between measures of processing speed and general intelligence (Deary, 1994; van Ravenzwaaij, Brown, & Wagenmakers, 2011). These prior studies have argued that processing speed is the core basis for ‘g’. However, genetic studies have found that the covariation between speed and intelligence is mostly due to shared genes (Luciano et al., 2005; Neubauer, Spinath, Riemann, Angleitner, & Borkenau, 2000), and have also provided evidence for genetic influences on speed that are separate from general intelligence, and vice versa (Luciano et al., 2001b; Luciano et al., 2004A, 2004b; Luciano et al., 2001a). Because the present study includes measures of processing speed, we also examined how the genetic architecture underlying the relationship among the conditions of the TMT might be altered after taking into account the genetic and environmental influences shared between general cognitive ability and the TMT conditions.

The present study utilizes data from the Vietnam Era Twin Study of Aging (VETSA), a sample of late middle-aged men, to: 1) estimate the relative importance of genetic and environmental influences on individual differences in the conditions of the D-KEFS TMT, 2) determine the extent to which the conditions of the D-KEFS TMT have shared or distinct genetic influences, and 3) examine how the covariation between general cognitive ability and the D-KEFS TMT alters the genetic architecture underlying the relationship among conditions of the D-KEFS TMT. Although we expect phenotypic analyses to reveal that each of the Trails conditions will load on a single latent factor, and that genetic influences will largely account for the correlations among the Trails conditions, we predict that genetic analyses will also reveal genetic influences specific to set shifting (Trails 4).

Methods

Sample

Data were obtained from Wave 1 of the Vietnam Era Twin Study of Aging (VETSA), a longitudinal study of cognition and aging beginning in midlife (Kremen et al., 2006). All participants in VETSA are from the Vietnam Era Twin Registry, a nationally representative sample of male–male twin pairs who served in the US military sometime between 1965 and 1975. Detailed descriptions of the Registry and ascertainment methods have been previously reported (Eisen, True, Goldberg, Henderson, & Robinette, 1987; Henderson et al., 1990). VETSA twins resemble those of the larger Registry sample and are representative of the general population of similarly-aged adult males in terms of demographic and health characteristics based on U.S. census and Center for Disease Control data (Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, 2007). VETSA twins had the option to travel to Boston University or to the University of California, San Diego, for a day-long session that included physical assessments and an extensive neurocognitive battery. The study was approved by local Institutional Review Boards in both Boston and San Diego. The VETSA Wave 1 sample includes 1237 individuals (347 monozygotic twin (MZ) pairs, 268 dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs and 7 unpaired twins). The average age was 55.4 years (range: 51–60). This narrow age range allows us to study genetic influences in late middle age prior to any age-related changes in later life.

Measures

The Delis-Kaplan Executive System (D-KEFS) Trail Making Test consists of five conditions (Delis, et al., 2001). Condition 1 (Trails 1) is a visual-search task that requires participants to scan a page and cross out all circles containing the number 3 (total items marked = 24). Trails 2 is a number sequencing task, similar to the traditional Trails A, in which participants draw lines to connect numbers in sequential order. Trails 3 requires participants to connect letters in sequential order. Trails 2 and Trails 3 each contain 16 items. Trails 4 measures set-shifting ability, analogous to the traditional Trails B. In this task, participants must switch between connecting numbers and letters in sequence. Trails 5 is a motor speed task in which participants must trace a dotted line that connects a series of open circles. This condition does not involve searching, sequencing, or number-letter shifting. Trails 4 and Trails 5 each contain 32 items. The score for each condition of the TMT was time in seconds; thus, higher scores indicate poorer performance. Note that the number of items to mark/connect differ across conditions; therefore, raw scores cannot be directly compared. It is also worth noting that each D-KEFS TMT condition uses a double size sheet of paper (17 × 11 in.), whereas the traditional TMT uses standard 8 × 10 in. sheets.

General cognitive ability was indexed by the Armed Forced Qualification Test (AFQT; Bayroff and Anderson, 1963), a 100-item multiple-choice, g-loaded test that is highly correlated (r .85) with Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) and other general cognitive ability measures (Uhlaner et al., 1952; McGrevy et al., 1974). The AFQT is also a highly reliable measure; the test-retest correlation over a 35-year interval was .74 in the VETSA sample (Lyons et al., 2009).

Statistical Analysis

Twin Design

Twin modeling relies on the fact that identical twins (monozygotic; MZ) and fraternal twins (dizygotic; DZ) vary in degree of genetic relatedness but share the same environmental influences (Neale & Maes, 2002). Twin models can, therefore, decompose the phenotypic variance of a trait into genetic and environmental variance components. There are two sources of genetic variance that can be estimated: additive (A) and dominance (D). Under an additive model, MZ twins correlate 1.0 on ‘A’ because they share 100% of their segregating genes while DZ twins correlate 0.50 because they share, on average, 50%. In contrast, dominance can refer to a non-additive pattern of inheritance and/or gene-gene interactions (epistasis). Under a dominance model, MZ twins correlate 1.0 on ‘D’ whereas DZ twins correlate 0.25 because they are share, on average, 25% of their dominance/epistatic effects. The proportion of the phenotypic variance attributable to total genetic factors (i.e., A+D) is known as the heritability (h2).

There are also two sources of environmental variance: shared or common environment (C) and non-shared environment (E). Based on standard assumptions of the twin model, both MZ and DZ twins share 100% (i.e. correlate 1.0) of their shared environmental influences (C), which are defined as non-genetic influences that make twins in the same family similar to one another. These might include growing up in the same house, having the same diet, going to the same school, etc. Conversely, non-shared environmental factors (E) refer to non-genetic influences that make twins different from one another, such as living in different regions, acquiring different diseases or injuries, or differential treatment by parents. E also includes measurement error. By definition, E does not correlate between either MZ or DZ twins.

Due to the limitations of the twin design, D and C cannot be estimated simultaneously, so both ACE and ADE models are routinely tested. For univariate analysis, the appropriate model to use can be inferred from comparing MZ and DZ correlations. If MZ correlations are less than or equal to twice the DZ correlations, an ACE model is used. If MZ correlations are greater than twice the DZ correlations, an ADE model is used. However, for multivariate genetic analysis, a better strategy is to employ formal model-fitting procedures to determine statistically whether an ACE or ADE model offers a better fit to the data.

Multivariate genetic models

Several multivariate models were fit to the data to determine the structure of shared genetic and environmental influences on the different D-KEFS TMT conditions. All models were fit to raw data using the structural equation modeling program, Mx (Neale, 2004). Initially, a saturated model was fit that perfectly recaptures the observed means and variances of all Trails measures. The fit of the saturated model provides a baseline comparison for subsequent models. Second, Cholesky decomposition models (ACE and ADE) were fit to the data; these estimate the underlying genetic and environmental variance/covariance matrix (Figure 1A). Cholesky models include the same number of A, C (or D) and E factors as variables in the model. For example, an ACE model fit to data from four variables would include four A factors, four C factors and four E factors. Cholesky models can estimate the heritability (h2 or a2) for each variable as well as the proportion of phenotypic variance attributable to shared environment (c2) and non-shared environment (e2). Additionally, genetic and environmental correlations between variables can be calculated (rg, rc, and re). Genetic correlations (rg) are used to estimate to what extent any two variables are determined by the same set of genetic factors. The shared (rc) and unique environmental (re) correlations are analogous. To determine whether genetic and/or environmental factors significantly contributed to the variance and covariance of the Trails measures, ACE, ADE, AE, CE, and E only Cholesky models were tested. The fit of each model was compared to fit of the saturated model.

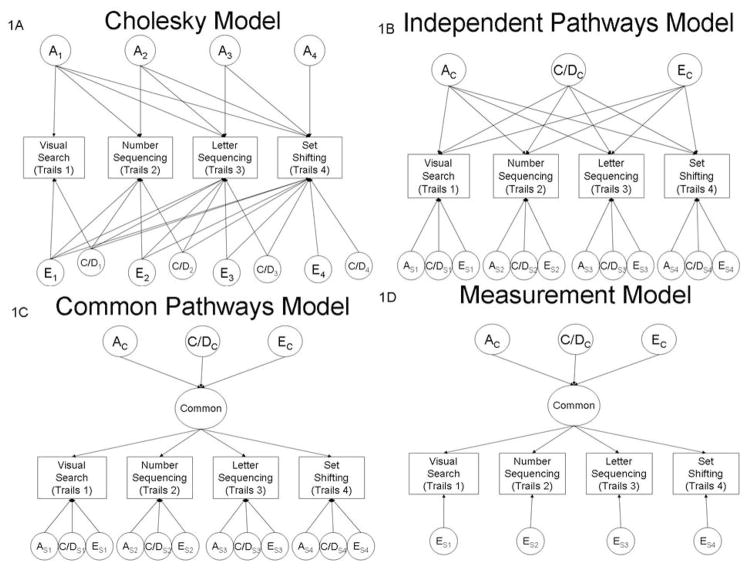

Figure 1.

Multivariate Genetic Models. Only one twin is represented in each figure. To note, for space reasons, only A (additive genetic) and E (non-shared environment) pathways are depicted. Figure 1A (Cholesky model), depicts the atheoretical, fully parameterized variance/covariance structure among Trails 1–4, including all source of variance: additive genetic influences (A1–A4) and non-shared environmental influences (E1–E4). Figures 1B (Independent Pathways Model), 1C (Common Pathways Model) and 1D (Measurement Model) depict theoretical models for the covariance structure among Trails 1–4. AC=Additive genetic influences and EC=Nonshared environmental influences that are common to all Trails conditions. AS=Additive genetic influences and ES=Nonshared environmental influences that are specific to each Trails condition.

While Cholesky models can give overall estimates of the relative importance of genetic and environmental influences on each measure, as well as calculate the degree to which these influences are shared across measures, they do not provide insight into the possible genetic and environmental factor structure underlying covariance across measures. Thus, to elucidate genetic and environmental factors underlying the covariance structure of the different Trails conditions, three behavioral genetic factor models were tested: 1) Independent Pathways model, 2) Common Pathways model, and 3) Measurement model. These models represent different patterns by which genetic and environmental influences may explain the observed phenotypic correlations among the Trails conditions. The Independent Pathways model (Figure 1B) assumes that a single set of genetic and environmental factors influences covariation among Trails conditions. These factors operate directly on each condition through independent genetic and environmental pathways, analogous to factor loadings (i.e. ac1, ac2, ac3, ac4, ec1, ec2, ec3, ec4). Thus, this model allows for the genetic or environmental influences on the covariation between different pairs of variables to differ. For example, the covariation between number sequencing (Trails 2) and letter sequencing (Trails 4) could be due primarily to genetic factors (high loadings for ac2 and ac4), whereas the covariation between visual search (Trails 1) and set shifting (Trails 4) could be due primarily to non-shared environmental factors (high loadings for ec1 and ec4). The Independent Pathways model allows for both genetic and environmental influences common to all measures (Ac, Cc or Dc, and Ec) and residual genetic and environmental influences (As1–As4, Es1– Es4, etc.) that are specific to each individual measure.

The Common Pathways model (Figure 1C) is a nested submodel of the Independent Pathways model (McArdle & Goldsmith, 1990). It assumes that a single underlying latent phenotype is solely responsible for the covariation among the Trails conditions. The variance of this latent phenotype is further partitioned into common genetic and environmental factors (Ac, Cc or Dc, and Ec). In this model, common genetic and environmental factors influence the covariance among measures via factors loadings (f1, f2, f3, f4) on the underlying latent phenotype. A key element of the Common Pathways model is its prediction that the phenotypic covariance is equally apportioned into genetic and environmental components for all combinations of variables. Thus, this model would predict that genetic factors account for the same proportion of covariance across all measures. Similar to the Independent Pathways model, the Common Pathways model allows for residual genetic and environmental influences (As1–As4, Es1– Es4, etc.) that are specific to each individual measure.

The Measurement model (Figure 1D) is a nested submodel of the Common Pathways model. The critical difference between these two models is that the Common Pathways model allows for genetic (As, Ds) and/or shared environmental (Cs) factors that are specific to each measure and do not influence the covariation among measures. In contrast, the Measurement model assumes that all genetic and shared environmental influences are operating through their effects on the latent phenotype. In this model, the residual variance for each measure that is not explained by the latent phenotype is assumed to be measurement error and is, therefore, modeled as specific non-shared environmental (Es) factors. Thus, this model is comparable to a phenotypic single factor model, which would predict that a single phenotype accounts for the covariance among all Trails measures, and that any unique variance in each measure is due entirely to measurement error.

Model fitting

Model fit was assessed using the difference in two times the log likelihood (-2LL) between nested models. The -2LL of two models are compared using the Likelihood Ratio Chi- Square (χ2) Test with degrees of freedom equal to the difference in the number of parameters between the two models; a significant (p < 0.05) increase in the Likelihood Ratio χ2 Test statistic indicates that the nested (i.e., reduced) model has a significantly poorer fit. One objective of model fitting is to use the fewest amount of parameters possible to describe the observed variance/covariance matrix. Thus, Akaike’s and Bayesian information criteria (AIC and BIC) were also utilized to help select the final model; lower AIC and BIC scores indicate greater parsimony, i.e., a better balance maximizing goodness of fit while minimizing the number of parameters required. Determination of the best model occurred through a series of hierarchical model comparisons. First, ACE and ADE Cholesky models were compared to the saturated model to determine which model most accurately captured the observed variance and covariance across measures. In addition, “reduced” Cholesky models were compared to the saturated model to determine: 1) if the effects of “A” were significant (CE and/or DE model), 2) if the effects of C (or D) were significant (AE model) and 3) if non-shared environment (E) accounted for all the variance/covariance across measures (E only model). In other words, these latter comparisons test whether dropping components from the model results in a significant worsening of fit to the data. Finally, the Independent Pathways model, Common Pathways model and Measurement model were compared to the Cholesky model to determine which factor model most parsimoniously accounted for the specific pattern of covariance among the Trails conditions. To determine the extent to which the results might be accounted for by general cognitive ability, we then tested the best-fitting model after adjusting scores on each of the Trails conditions for AFQT scores.

Results

Phenotypic Analyses

Raw means (in seconds) and standard deviations for each Trails condition were: M = 11.14, sd = 5.43 (visual search, Trails 1,), M=12.98, sd=12.46 (number sequencing, Trails 2), M=12.03, sd=13.46 (letter sequencing, Trails 3), M=31.34, sd = 35.32 (set shifting, Trails 4), an M=23.82, sd=8.67 (motor speed, Trails 5). The distribution for each Trails condition was positively skewed and was therefore transformed using a Box-Cox transformation and then standardized (M=0, sd=1). Phenotypic correlations among the five Trails conditions, along with the correlation between each Trails condition and AFQT, are reported in Table 1. Correlations ranged from 0.29–0.60, with the highest correlation between number sequencing and letter sequencing. Number sequencing and letter sequencing also showed similar magnitudes of association with visual search (0.37 and 0.38) and set shifting (0.50 and 0.54). Set shifting correlated more strongly with both number sequencing and letter sequencing than with visual search. Motor speed had similar correlations (ranging from 0.33–0.38) with each of the other conditions. Phenotypic factor analysis using extracted one factor that accounted for 42% of the variance for the five Trails conditions. All phenotypic analyses were conducted in SPSS for Windows (Version 18). General cognitive ability (as measured by AFQT) was also correlated moderately with all four Trails conditions, with Pearson’s correlations ranging from −0.19 (visual search) to −0.48 (set shifting/executive function (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Pearson correlations among Trails conditions and between each Trails measure and general cognitive ability

| Visual Search (Trails 1) | Number Sequencing (Trails 2) | Letter Sequencing (Trails 3) | Set Shifting (Trails 4) | Motor Speed (Trails 5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Search (Trails 1) | - | ||||

| Number Sequencing (Trails 2) | 0.38** | - | |||

| Letter Sequencing (Trails 3) | 0.37** | 0.60** | - | ||

| Set Shifting (Trails 4) | 0.29** | 0.50** | 0.54** | - | |

| Motor Speed (Trails 5) | 0.38** | 0.35** | 0.38** | 0.33** | - |

| General Cognitive Ability (AFQT) | −0.19** | −0.34** | −0.38** | −0.48** | −0.23** |

Note:

p < 0.01

Twin Correlations

Univariate cross-twin (intraclass) correlations for each zygosity group (based on estimates from the saturated model) revealed that, within Trails 1 –4, MZ correlations were higher than DZ correlations (Table 2), suggesting that genetic factors influence individual differences in each condition. Likewise, cross-trait, cross-twin MZ correlations were higher than cross-trait, cross-twin DZ correlations for Trails 1–4 (Table 2); these correlations provide evidence that genetic factors further contribute to the covariance among these Trails conditions. An example of a cross-trait, cross-twin correlation would be the correlation of Twin A’s number sequencing with Twin B’s set shifting. For visual search, univariate MZ correlations, as well as cross-trait, cross-twin MZ correlations with number sequencing and letter sequencing, were more than twice the DZ correlations, suggesting D (non-additive) effects. However, all other univariate MZ correlations (for number sequencing, letter sequencing and set shifting) and cross-trait, cross-twin MZ correlations were less than twice the DZ correlations, suggesting some C (shared environment) effects.

Table 2.

Intraclass and cross-trait, cross-twin correlations among Trails conditions, by zygosity

| Visual Search (Trails 1) | Number Sequencing (Trails 2) | Letter Sequencing (Trails 3) | Set Shifting (Trails 4) | Motor Speed (Trails 5) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MZ | DZ | MZ | DZ | MZ | DZ | MZ | DZ | MZ | DZ | |

| Visual Search (Trails 1) | 0.36 | 0.13 | ||||||||

| Number Sequencing (Trails 2) | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.21 | ||||||

| Letter Sequencing (Trails 3) | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.41 | 0.26 | ||||

| Set Shifting (Trails 4) | 0.28 | 0.14 | 0.40 | 0.23 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.60 | 0.37 | ||

| Motor Speed (Trails 5) | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.24 |

Note:

p < 0.05

p < 0.01 Estimates from saturated model

For presentation purposes, correlations were estimated using double entered data.

For model fitting comparisons, twins were randomly assigned to be either Twin 1 or Twin 2.

MZ = monozygotic twin, DZ=dizygotic twin, Intraclass correlations in bold

Number of pairs utilized in this analysis: MZ twin pairs = 342, DZ twin pairs = 266

The pattern of correlations also revealed that, although motor speed was phenotypically correlated with other Trails conditions (r = 0.33 – 38), it was not heritable. In fact, the dizygotic (DZ) twin correlation (r=0.24) was slightly, but not significantly, higher than that of monozygotic (MZ) twins (r = 0.17) for motor speed. In addition, the MZ cross-trait, cross-twin correlations with motor speed were higher than the respective DZ correlations for visual search and set shifting, but the DZ cross-trait, cross-twin correlations were higher than or equal to the respective MZ correlations for number sequencing, letter sequencing and set shifting. This pattern of correlations makes it difficult to model the relationship of motor speed to the other Trails conditions using existing twin models. Thus, motor speed was excluded from the subsequent multivariate genetic analysis. We therefore re-ran the phenotypic factor analysis on the remaining four Trails conditions (visual search, number sequencing, letter sequencing, and set shifting). Again, one factor was extracted that accounted for 46% of the variance among these four measures.

Multivariate Genetic Analysis of Unadjusted Trails Conditions

In multivariate genetic analysis of visual search, number sequencing, letter sequencing, and set shifting, both the ACE and ADE Cholesky models (Models 2 and 3 in Table 3) fit well compared to the saturated model based on the Likelihood Ratio (χ2) Test. Cholesky models without additive genetic effects (CE model, Model 5, and E only, Model 6) fit significantly more poorly than the saturated model, while the model without either shared environmental or dominance genetic effects (AE model, Model 4) did not fit significantly more poorly than the saturated model. In addition, AIC and BIC values indicated that the most parsimonious Cholesky model was the AE model (Model 4) that included only additive genetic and non-shared environmental effects. For comparison with other studies, genetic (rg) and non-shared environmental (re) correlations were calculated from the parameters estimated from the AE Cholesky model. Genetic correlations ranged from 0.63 to 0.96, with the highest correlation being between number sequencing and letter sequencing. Moreover, the 95% confidence interval for the genetic correlation between number and letter sequencing included 1.0, indicating complete overlap of genetic factors. In contrast, genetic correlations were smaller for correlations with visual search and set-shifting, and 95% confidence intervals did not include 1.0, indicating some specificity of genetic influence for these two conditions. Non-shared environmental correlations across conditions were lower compared to the genetic correlations, and ranged from 0.05 to 0.35.

Table 3.

Model Fitting Results

| Absolute Fit | Relative fit | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −2LL | df | AIC | BIC | Model comparison | Likelihood Ratio χ2 test | Δdf | p | |

| 1. Saturated | 12214.125 | 4812 | 2590.13 | −9366.72 | - | - | - | |

| 2. ACE Cholesky | 12275.166 | 4863 | 2549.17 | −9500.20 | 1 | 61.041 | 51 | 0.159 |

| 3. ADE Cholesky | 12275.067 | 4863 | 2549.07 | −9500.24 | 1 | 60.942 | 51 | 0.161 |

| 4. AE Cholesky | 12277.498 | 4873 | 2531.50 | −9531.19 | 1 | 63.373 | 61 | 0.393 |

| 5. CE Cholesky | 12315.396 | 4873 | 2569.40 | −9512.24 | 1 | 101.271 | 61 | 0.001 |

| 6. E Cholesky | 12540.993 | 4883 | 2774.99 | −9431.60 | 1 | 326.868 | 71 | 0.000 |

| 7. AE Independent Pathways (IP) Model | 12283.642 | 4877 | 2529.64 | −9540.98 | 4 | 6.144 | 4 | 0.189 |

| 7a. AE IP, specific A for Trails 1 and Trails 4, specific E all† | 12284.693 | 4879 | 2526.69 | −9546.89 | 7 | 1.051 | 2 | 0.591 |

| 8. AE Common Pathways Model | 12305.427 | 4880 | 2545.43 | −9539.73 | 4 | 27.929 | 7 | 0.000 |

| 9. AE Measurement Model | 12374.002 | 4884 | 2606.00 | −9518.31 | 4 | 96.501 | 11 | 0.000 |

denotes final model

Given the lack of evidence for significant shared environmental (C) or dominance genetic (D) effects, we compared subsequent AE factor models to the AE Cholesky model (Table 3). The AE Common Pathways model (Model 8) and the Measurement model (Model 9) fit significantly more poorly than the AE Cholesky model and higher AIC and BIC values, providing evidence that a single common phenotype does not adequately describe the shared variance among the Trails conditions. In contrast, the AE Independent Pathways model (Model 7) did not fit the data significantly more poorly than the AE Cholesky model (non-significant χ2 test); AIC and BIC values were also lowest for the AE Independent Pathways model, indicating that this was the most parsimonious model. Thus, since the AE Independent Pathways model described the data as well as the AE Cholesky model while using fewer parameters, we selected this model as our model that best describes the pattern of genetic and environmental influences on the four Trails conditions. Further examination of parameter estimates from the full AE Independent Pathways model (available from first author) revealed that there were non-significant estimates for specific genetic (As) influences on number sequencing (As2 = 0.01, 95%CI 0.00–0.07) and letter sequencing (As3 = 0.04, 95%CI 0.00–0.09), and dropping these two paths from the model (Model 7a) did not result in a significant deterioration of fit compared to the full AE Independent Pathways Model. Thus, the most parsimonious model based on AIC and BIC statistics was an Independent Pathways model that included both a common genetic factor (AC) and a common non-shared environmental factor, (EC) as well as significant genetic influences (AS) that were specific to visual search and set shifting and specific non-shared environmental influences (Es) for each Trails condition (Figure 2a).

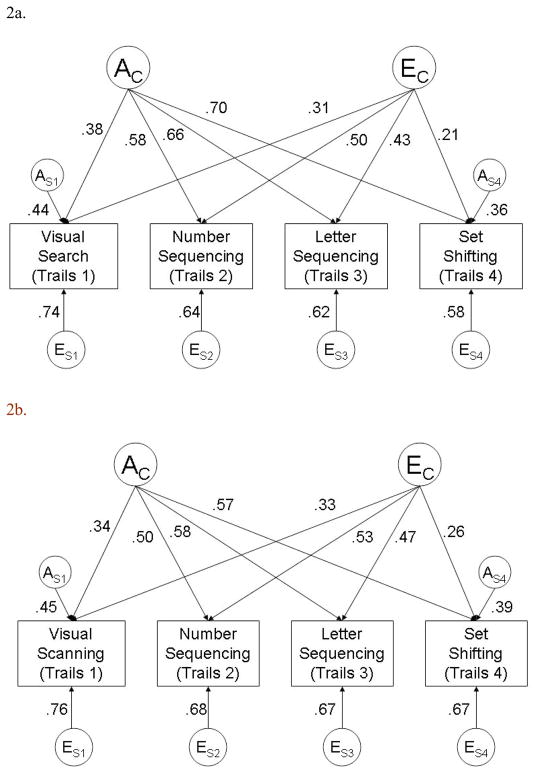

Figure 2.

Most parsimonious independent pathway model for the covariation among D-KEFS Trail Making Test conditions, for Trails values that were a) not adjusted for general cognitive ability and b) adjusted for general cognitive ability. AC = common genetic factor; EC = common non-shared environmental factor; AS1 = specific genetic factor for visual searching condition; AS2 = specific genetic factor for set shifting; ES1–4 = specific non-shared environmental factors on each condition.

To estimate the heritability of each Trails condition from Model 7a, we first squared the parameter estimates for each condition from both the common genetic (AC) factor and the specific genetic (As) factor. Then, these squared estimates were summed to estimate the total heritability for each Trails condition. Heritability estimates calculated from Model 7a were: visual search (h2 = 0.35), number sequencing (h2 = 0.34), letter sequencing (h2 = 0.43), and set shifting (h2 = 0.62). Similar calculations were used to estimate the total effects of non-shared environmental influences on each condition. The contributions from common and specific factors on the total genetic and non-shared environmental influences on each Trails condition are given in Table 4 (Panel a). While common genetic factors accounted for a significant proportion of the heritability for all four Trails conditions, the majority (57%) of visual search heritability was explained by the specific genetic factors that were separate from the common genetic factor. Likewise, a significant proportion (21%) of the total heritability of set-shifting was also attributable to specific genetic factors not shared with the other Trails conditions. These specific genetic influences accounted for 13% of the total phenotypic (i.e., genetic + environmental) variance in set-shifting. In contrast, 100% of the heritability of both number and letter sequencing was accounted for by the common genetic factor. For all measures, the majority of the total non-shared environmental influences on each Trails condition (62–89%) were explained by specific factors separate from the common non-shared environmental factor.

Table 4.

Portion of total genetic (h2) and environmental (e2) variance for each Trails condition explained by common and specific factors, with 95% confidence intervals, for Trails values that were a) not adjusted and b) adjusted for general cognitive ability

| Proportion of total variance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common genetic variancea | Specific genetic varianceb | Total genetic variance (h2) | Common nonshared environmental variancec | Specific nonshared environmental varianced | Total nonshared environmental variance (e2) | |

|

a) Results from Analyses using Unadjusted Trails Measures

| ||||||

| Visual Search (Trails 1) | 0.15 | 0.20 |

0.35 0.25–0.45 |

0.10 | 0.55 |

0.65 0.57–0.75 |

| 0.10–0.22 | 0.12–0.28 | 0.05–0.17 | 0.47–0.34 | |||

| 43% | 57% | 15% | 85% | |||

| Number Sequencing (Trails 2) | 0.34 | -- |

0.34 0.26–0.43 |

0.25 | 0.41 |

0.66 0.59–0.74 |

| 0.26–0.43 | 0.16–0.37 | 0.32–0.48 | ||||

| 100% | 38% | 62% | ||||

| Letter Sequencing (Trails 3) | 0.43 | -- |

0.43 0.34–0.53 |

0.19 | 0.38 |

0.57 0.50–0.65 |

| 0.34–0.53 | 0.12–0.28 | 0.32–0.44 | ||||

| 100% | 33% | 67% | ||||

| Set Shifting (Trails 4) | 0.49 | 0.13 |

0.62 0.53–0.72 |

0.04 | 0.34 |

0.38 0.33–0.44 |

| 0.39–0.61 | 0.05–0.20 | 0.02–0.09 | 0.29–0.39 | |||

| 79% | 21% | 11% | 89% | |||

|

| ||||||

|

b) Results from Analyses using Adjusted Trails Measures

| ||||||

| Visual Search (Trails 1) | 0.12 | 0.20 |

0.32 0.22–0.42 |

0.11 | 0.58 |

0.68 0.60–0.78 |

| 0.06–0.18 | 0.12–0.28 | 0.10–0.17 | 0.49–0.67 | |||

| 36% | 64% | 15% | 85% | |||

| Number Sequencing (Trails 2) | 0.25 | -- |

0.25 0.17–0.34 |

0.28 | 0.47 |

0.75 0.66–0.84 |

| 0.18–0.32 | 0.18–0.41 | 0.37–0.54 | ||||

| 100% | 38% | 62% | ||||

| Letter Sequencing (Trails 3) | 0.34 | -- |

0.34 0.24–0.43 |

0.22 | 0.45 |

0.67 0.59–0.76 |

| 0.25–0.41 | 0.14–0.32 | 0.37–0.52 | ||||

| 100% | 33% | 67% | ||||

| Set Shifting (Trails 4) | 0.33 | 0.15 |

0.48 0.38–0.58 |

0.07 | 0.45 |

0.52 0.46–0.60 |

| 0.24–0.59 | 0.06–0.23 | 0.03–0.12 | 0.38–0.51 | |||

| 69% | 31% | 13% | 87% | |||

Notes: Because we used standardized variables in our analyses, actual estimates for each variance component translate into the proportion of total variance (genetic + environmental) explained

estimate due to common genetic factor and percentage of total genetic variance

estimate due to specific genetic factor and percentage of total genetic variance

estimate due to common nonshared environmental factor and percentage of total nonshared environmental variance

estimate due to specific nonshared environmental factor and percentage of total nonshared environmental variance

parameter fixed to zero.

In addition, the parameter estimates shown in Figure 2a can be used to calculate the extent to which phenotypic correlations among the various Trails conditions are due to common genetic versus common non-shared environmental factors. For example, to calculate the total phenotypic correlation between visual search and set shifting, first the AC pathways for visual search and set shifting are multiplied together (0.38 × 0.70 = 0.27) and the EC pathways for visual search and set shifting are multiplied together (0.31 × 0.21 = .07). These products are then added together to calculate the total phenotypic correlation (rp = 0.34). To estimate to what extent genetic factors contribute to this correlation, the product of the AC pathways is divided by the total phenotypic correlation (0.27/0.34 = 0.79). This indicates that 79% of the correlation between visual search and set shifting is due to genetic factors. Similar calculations can be performed to determine the influences of non-shared environmental factors on the phenotypic correlations. These calculated phenotypic correlations and the proportions due to genetic and environmental factors are reported in Panel a of Table 5. Genetic factors accounted for the majority (58–84%) of the phenotypic correlations among the four Trails conditions.

Table 5.

Genetic (A) and environmental (E) contributions to the phenotypic correlations (rp) among Trails measures, calculated from best-fitting independent pathway model, for Trails values that were a) not adjusted and b) adjusted for general cognitive ability

| a) Results from Analyses using Unadjusted Trails Measures | rp | % A | % E |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Search (Trails 1) – Number Sequencing (Trails 2) | 0.38 | 58 | 42 |

| Visual Search (Trails 1) – Letter Sequencing (Trails 3) | 0.38 | 68 | 32 |

| Visual Search (Trails 1) – Set Shifting (Trails 4) | 0.34 | 79 | 21 |

| Number Sequencing (Trails 2) – Letter Sequencing (Trails 3) | 0.60 | 63 | 37 |

| Number Sequencing (Trails 2) – Set Shifting (Trails 4) | 0.52 | 79 | 21 |

| Letter Sequencing (Trails 3) – Set Shifting (Trails 4) | 0.55 | 84 | 16 |

|

| |||

| b) Results from Analyses using Adjusted Trails Measures | rp | % A | % E |

|

| |||

| Visual Search (Trails 1) – Number Sequencing (Trails 2) | 0.34 | 50 | 50 |

| Visual Search (Trails 1) – Letter Sequencing (Trails 3) | 0.36 | 55 | 45 |

| Visual Search (Trails 1) – Set Shifting (Trails 4) | 0.28 | 69 | 31 |

| Number Sequencing (Trails 2) – Letter Sequencing (Trails 3) | 0.54 | 54 | 46 |

| Number Sequencing (Trails 2) – Set Shifting (Trails 4) | 0.42 | 67 | 33 |

| Letter Sequencing (Trails 3) – Set Shifting (Trails 4) | 0.45 | 73 | 27 |

Genetic Analyses of Trails Conditions Adjusted for General Cognitive Ability

To determine whether the associations with general cognitive ability influenced the prior pattern of results, addition genetic models were conducted after adjusting each of the four Trails conditions for general cognitive ability. As in the initial analyses, an AE Independent Pathways model (see Figure 2b) fit the data well as compared to the AE Cholesky model (Likelihood Ratio χ2 test = 4.75, df = 4, p =0.31 ). Furthermore, both visual search (0.45; 95%CI 0.34 – 0.53) and set shifting/executive function (0.39; 95%CI 0.20 – 0.48) still had specific genetic influences that were separate from the common genetic factor. Likewise, specific genetic influences on letter and number sequencing were not significant. Not surprisingly, after adjusting for general cognitive ability, the overall heritability of each Trails condition was decreased, with estimated heritabilities ranging from 0.25 (visual search) to 0.48 (set shifting/executive function) (see Panel b of Table 4). However, even though the total heritability of set-shifting was somewhat lower in analyses adjusting for general cognitive ability (0.48 versus 0.62), the heritability of set-shifting was still substantial, and the proportion of the total heritability attributable to specific genetic factors not shared with the other Trails conditions increased from 21% (in the unadjusted analyses) to 32% (see Table 4). Moreover, the specific genetic influence on set-shifting after adjusting for general cognitive ability still accounted for 15% of the overall phenotypic variance in the adjusted analyses. Likewise, as in the unadjusted analyses, genetic factors accounted at least half (50–73%) of the phenotypic correlations among the four Trails conditions, even after controlling for general cognitive ability.

Discussion

The twin design goes beyond phenotypic analysis to determine how genetic and environmental factors influence individual differences in a trait and the covariance between traits. In the present study, we examined the genetic architecture underlying four conditions of the D-KEFS Trail Making Test. Whereas phenotypic factor analysis revealed one factor that accounted for the covariance among Trails conditions, genetic analysis suggested a more complex covariance structure. Our results indicated that a single common genetic factor and a single common non-shared environmental factor accounted for the phenotypic covariance among Trails conditions with genes accounting for the majority of the covariance between these conditions. This common genetic factor accounted for all of the genetic influences on number and letter sequencing. However, our analyses also revealed distinct genetic influences specific to visual search and set shifting that were independent of the common genetic factor. This pattern of results remained even after controlling for general cognitive ability.

Heritability of D-KEFS Trail Making Test

Heritability estimates for number sequencing (0.34) and of set shifting (0.65) based on the most parsimonious Independent Pathways model are in accordance with previous reports of the heritability of their analogous conditions from the traditional TMT (Trails A and B) (Buyske, et al., 2006; Pardo, et al., 2006; Swan & Carmelli, 2002). To our knowledge, this is first study to show that visual search (h2 = 0.35) and letter sequencing (h2 = 0.43) conditions from the D-KEFS TMT are also moderately heritable. For motor speed, patterns of intraclass twin correlations were inconsistent with the other Trails measures, with the DZ pair correlations (0.24) slightly higher (albeit non-significantly) than MZ correlations (0.17), indicating that genetic factors did not contribute to the variation in this measure. However, other twin studies of motor speed using different measures have demonstrated that this domain is heritable (Fox et al., 1996; Finkel et al., 2000). Our findings indicate this specific test of motor speed (Trails 5), in this sample, is not heritable. Given the inconsistency of our results with other twin studies that have used other tests of motor speed, this result will need to be replicated in other studies that use Trails 5 as a measure of motor speed. However, as we demonstrated for the WCST, heritability of a cognitive domain does not necessarily mean that every individual test relating to a particular domain is heritable (Kremen et al., 2007; Kremen and Lyons,, 2011). Because of the unexpected pattern of correlations for Trails 5, this measure was not included in out multivariate genetic analysis.

Common Genetic Factor Underlies Relationship among Trails Conditions

Our multivariate genetic analyses uncovered a single common genetic factor and a single common environmental factor that accounted for the covariance among the conditions 1–4 of the D-KEFS Trails Making Test. Overall, the majority of the phenotypic correlations between Trails conditions was explained by genetic factors. Furthermore, from the Cholesky model, genetic correlations, i.e. the degree that these conditions share the same genetic influences, were high (ranging from 0.63 to 0.96). However, both visual search and set shifting had genetic influences separate from the common genetic factor (discussed more below) while all of the genetic influences on number sequencing and letter sequencing were explained by the common genetic factor. Number sequencing and letter sequencing, which both measure processing speed and simple sequencing abilities, were moderately phenotypically correlated (r = 0.60), but the genetic influences on these conditions completely overlapped and were responsible for most of the phenotypic correlation. The complete overlap of genetic influences, combined with the modest environmental correlation, suggests that any differences between number and letter sequencing are due to non-shared environmental factors, most likely measurement error, and suggests that number and letter sequencing tap into the same underlying cognitive process.

The finding of a common genetic factor that accounts for the majority of the covariation among these measures is perhaps not surprising, given that each condition is a variant of the same test. One possible interpretation is that the common genetic factor found in the present study reflects general ability (g), which often explains the shared variance of specific cognitive abilities (Johnson et al., 2004; Petrill et al., 1998; Bouchard and McGue, 2003). However, when we empirically tested whether the overlap of general cognitive ability with each Trails condition affected the underlying genetic architecture of the four Trails conditions, we found a similar pattern of results. Even after controlling for genetic and environmental influences shared between each Trails condition and general cognitive ability, the best-fitting model for the adjusted Trails conditions revealed a common genetic factor that accounted for the covariation among the Trails conditions, and this common genetic factor accounted for between 50–73% of the phenotypic correlations across the Trails condition.

Therefore, in our view, a more likely interpretation is that this common genetic factor represents processing speed and sequencing abilities that are independent from general cognitive ability. Processing speed is common to all four conditions and sequencing is common to at least three of the four (Trails 2–4). Processing speed is likely the dominant component because sequencing in numerical and alphabetical order requires little in the way of cognitive resources because they are so automated and over-learned. It can also be argued the visual search subtest contains a sequencing component, but it differs from that of the other subtest because is the only one in which sequencing would have to be imposed as a strategy by the participant. In other words, stimuli could be canceled haphazardly or more efficiently by working in sequence (e.g., across rows or down columns).

In this context, it is important to address the extensive literature on the relationship between intelligence and speed(Deary 1994; van Ravenzwaaij, et al., 2011). While most studies report a substantial phenotypic relationship between processing speed and IQ (Grudnik & Kranzler, 2001), genetic studies of processing speed and IQ have found that a significant portion of genetic variance in IQ is not shared with speed. These genetic studies indicate that there are clearly different cognitive abilities independent from processing speed that also account for the variance in IQ (Lee et al., 2011; Luciano, et al., 2001b; Luciano, et al., 2004a; Luciano, et al., 2001a; Neubauer, et al., 2000). Likewise, genetic studies have also provided evidence for genetic influences specific to processing speed that are independent from IQ (Luciano, et al., 2004b; Luciano, et al., 2001a). Furthermore, other genetic studies provide evidence against a causative model of processing speed and IQ, instead suggesting that the covariation between intelligence and processing speed is explained by pleiotropy (i.e. same genes influence IQ and speed) (Luciano, et al., 2005). Moreover, there is evidence that different measures of processing speed differentially relate to intelligence (Deary, Johnson, & Starr, 2010). The results of the current study parallel these results from other twin samples in that even after adjusting each Trails measure for general cognitive ability, we still found evidence for a common genetic (as well as nonshared environmental) factor that accounted for the covariation among the conditions. It, therefore, seems that the common genetic factor from the final Independent Pathways model likely reflects mostly processing speed abilities along with some sequencing abilities that are independent from general cognitive ability.

Distinct genetic influences on visual search and set shifting

While a common genetic factor accounted for the majority of the phenotypic correlations among the Trails measures, we also found evidence to suggest that distinct genetic factors, in addition to specific environmental factors, contribute to the differences among these measures. The majority (57%) of the heritability of the visual search condition was due to specific genetic influences. This is particularly interesting because we did not initially hypothesis that visual search would have genetic influences distinct from the other Trails measure. Because the other conditions involve some visual searching as well, the question arises as to what cognitive processes are indexed by the significant specific genetic factors for visual search. One explanation is that these distinct genetic influences reflect specific searching abilities. Visual searching is more prominent in Trails 1 as compared to the other Trails conditions. The other Trails conditions generally require more limited searching of the visual field because the next letter or number in the sequence in never extremely far from the current one. The sequencing required for the other three Trails conditions provides an additional cognitive demand but it also provides additional structure, i.e., an organizational schema, to the task. On the visual search condition, however, examinees must impose their own organizational schema onto the task; that is, it is the only condition where sequencing is not pre-defined. For example, the target stimuli could be marked in haphazard fashion or could be marked systematically from left to right or from top to bottom. Individuals with an organized, systematic strategy are likely to be faster on the visual search condition. Therefore, the specific genetic influences on this condition could represent genes that are important for actively planning and/or organizing a task as well as visual searching.

Set shifting was moderately correlated (r = 0.50–0.54) with both number sequencing and letter sequencing, and modestly correlated r = 0.29 with visual search. Genes highly influenced these correlations, with 79–84% of these correlations due to genetic influences. Nevertheless, a modest, yet significant portion (21–32%) of the heritability of set shifting was distinct from the common genetic factor that accounted for shared genetic variance among the Trails conditions. Moreover, in both genetic models (unadjusted and adjusted for general cognitive ability), these specific genetic influences accounted for 13–15% of the total phenotypic variance in set-shifting. Although there is little doubt among most neuropsychologists and cognitive scientists that the set-shifting component of the TMT reflects a different cognitive process from the processing speed and sequencing components, it can be difficult to show statistically. That was the case in our phenotypic analysis, which found only a single underlying factor accounting for covariance across conditions. However, while our genetic analyses also indicated a common genetic factor across conditions, these analyses further showed that there were independent genetic influences on set shifting. There is also support from molecular genetic literature that there are specific genes that underlie executive function, particularly set-shifting. For example, Baune et al. (2010) demonstrated that haplotypes of the Reelin (RELN) gene, which is associated with neurodevelopment, were significantly associated with set shifting. We think the most logical inference is that these specific effects are genetic influences on the executive function of set-shifting ability that can be differentiated from genetic influences on processing speed and/or sequencing.

Our phenotypic results are therefore consistent with results of phenotypic analysis of various cognitive tasks reported by Salthouse and colleagues (Salthouse et al., 2003; Salthouse, 2005), which showed that executive functioning could not be separated from processing speed. On the other hand, results from our genetic analysis are also consistent with the genetic analysis of Friedman et al. (Friedman, et al., 2008) who found evidence for distinct genetic influences on executive functions and processing speed. Moreover, not only did the current genetic analysis reveal significant specific genetic influence on both visual searching and processing speed, but a comparison of our three factor models demonstrated that both models that assumed that a single latent phenotypic factor accounted for all covariance across conditions (i.e., the Common Pathways and Measurement models) did not fit the data well, supporting the hypothesis that the different Trails conditions are not tapping into only one underlying latent cognitive phenotype.

All of these behavioral genetic studies extend the work of Delis et al. (2003) in important ways. Specifically, Delis et al. (2003) noted the limitations of applying shared variance techniques such as factor analysis for assessing cognition in non-patient populations. While our phenotypic results are consistent with those limitations, our multivariate twin analysis was able to detect specific genetic effects on certain Trails conditions in our non-patient sample. Therefore, even though the common factor accounted for the majority of variance, we think it is important to highlight the specific genetic effects that were observed.

Our finding that set shifting has distinct genetic influences from processing speed and sequencing ability in the TMT may have implications for cognitive changes associated with aging or with particular neuropsychiatric disorders. For example, while both number sequencing and set shifting have been shown to decline with age, some research has suggested that performance on set shifting declines more rapidly (Rasmusson, et al., 1998). This difference is consistent with greater frontal lobe changes with age, as compared to other brain regions (Raz, Williamson, Gunning-Dixon, Head, & Acker, 2000). Our results further suggest that it may be important to consider the distinct genetic influences on set shifting and possible changes in genes or gene expression that may account for this phenomenon.

Limitations and Strengths

Several limitations should be considered while reviewing our findings. First, our findings may not be generalizable to women. Similarly, our sample consists mostly of Caucasians, limiting the ability to generalize our findings to other racial and ethnic groups. Another potential limitation was the exclusion of the Trails 5 condition (motor speed) from our genetic analyses. While we were able to examine the phenotypic relationship of Trails 5 with the other Trails conditions, we did not include Trails 5 in our multivariate genetic analysis because it was not heritable.

Nonetheless, the major strength of our study was the ability to utilize the twin design to evaluate the interrelationships among the D-KEFS TMT conditions. By using the twin design, we were able to determine that genes substantially contribute to the correlations among these measures and that the same set of genetic influences underlies both number and letter sequencing. Most importantly, the twin design allowed us to determine that both visual searching/organization and set shifting/executive function components had specific genetic influences separate from the processing speed/sequencing components. This finding supports the notion that these two conditions are, in part, measuring distinct cognitive processes. In addition, we were able to show that these effects were over and above any influence of general cognitive ability. Our findings provide further support for the importance of examining the genetic underpinnings of cognition because genetic (twin) analysis may uncover distinct processes that are obscured by standard phenotypic shared-variance techniques.

Acknowledgments

The United States Department of Veterans Affairs has provided financial support for the development and maintenance of the Vietnam Era Twin (VET) Registry. Numerous organizations have provided invaluable assistance in the conduct of this study, including: Department of Defense; National Personnel Records Center, National Archives and Records Administration; the Internal Revenue Service; National Opinion Research Center; National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences; the Institute for Survey Research, Temple University. The current VETSA project is supported by grants from NIH/NIA (R01 AG018386, R01 AG018384, R01 AG022381, and R01 AG022982). Most importantly, the authors gratefully acknowledge the continued cooperation and participation of the members of the VET Registry and their families. Without their contribution this research would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/neu

Contributor Information

Terrie Vasilopoulos, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

Carol E. Franz, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA.

Matthew S. Panizzon, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA.

Hong Xian, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO.

Michael D. Grant, Department of Psychology, Boston University, Boston, MA.

Michael J Lyons, Department of Psychology, Boston University, Boston, MA.

Rosemary Toomey, Department of Psychology, Boston University, Boston, MA.

Kristen C. Jacobson, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

William S. Kremen, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, and VA San Diego Healthcare System, La Jolla, CA.

References

- Alarcón M, Plomin R, Fulker DW, Corley R, DeFries JC. Molarity not modularity: Multivariate genetic analysis of specific cognitive abilities in parents and their 16-year-old children in the Colorado adoption project. Cognitive Development. 1999;14(1):175–193. [Google Scholar]

- Army Individual Test Battery. Manual of directions and scoring. War Department, Adjutant General’s Office; Washington, DC: 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Bayroff AG, Anderson AA. Development of Armed Forces Qualification Tests 7 and 8. Arlington, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute; 1963. Technical Research Report 1122. [Google Scholar]

- Beckham J, Crawford A, Feldman M. Trail making test performance in Vietnam combat veterans with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1998;11(4):811–819. doi: 10.1023/A:1024409903617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie C, Harvey P. Administration and interpretation of the Trail Making Test. Nature Protocols. 2006;1(5):2277–2281. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buyske S, Bates M, Gharani N, Matise T, Tischfield J, Manowitz P. Cognitive traits link to human chromosomal regions. Behavior Genetics. 2006;36(1):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10519-005-9008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. Health Data Interactive. Retrieved April 20, 2007: www.cdc.gov/nchs/hdi.htm.

- Corrigan J, Hinkeldey N. Relationships between parts A and B of the Trail Making Test. Journal of clinical psychology. 1987;43(4):402–409. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198707)43:4<402::aid-jclp2270430411>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca CR, Wood SJ, Anderson V, Buchanan JA, Proffitt TM, Mahony K, Pantelis C. Normative data from the Cantab. I: Development of executive function over the lifespan. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2003;25(2):242–254. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.2.242.13639. [Article] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deary IJ. Intelligence and auditory-discrimination - Separating processing speed and fidelity of stimulus representation. Intelligence. 1994;18(2):189–213. [Google Scholar]

- Deary IJ, Johnson W, Starr JM. Are processing speed tasks biomarkers of aging? Psychology of Aging. 2010;25(1):219–228. doi: 10.1037/a0017750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis D, Kaplan E, Kramer J. The Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Eisen S, True W, Goldberg J, Henderson W, Robinette CD. The Vietnam Era Twin (VET) Registry - Methond of Construction. Acta Geneticae Medicae Et Gemellologiae. 1987;36(1):61–66. doi: 10.1017/s0001566000004591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman N, Miyake A, Young S, DeFries J, Corley R, Hewitt J. Individual differences in executive functions are almost entirely genetic in origin. Journal of experimental psychology General. 2008;137(2):201. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.137.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovagnoli A, Del Pesce M, Mascheroni S, Simoncelli M, Laiacona M, Capitani E. Trail making test: normative values from 287 normal adult controls. The Italian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 1996;17(4):305–309. doi: 10.1007/BF01997792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grudnik JL, Kranzler JH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between intelligence and inspection time. Intelligence. 2001;29(6):523–535. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson WG, Eisen S, Goldberg J, True WR, Barnes JE, Vitek ME. The Vietnam Era Twin Registry-A Resource for Medical Research. Public Health Reports. 1990;105(4):368–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremen WS, Jacobson KC, Panizzon MS, Xian H, Eaves LJ, Eisen SA, Tsuang MT, Lyons MJ. Factor Structure of Planning and Problem-solving: A Behavioral Genetic Analysis of the Tower of London Task in Middle-aged Twins. Behavior Genetics. 2009;39(2):133–144. doi: 10.1007/s10519-008-9242-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremen WS, Jacobson KC, Xian H, Eisen S, Eaves LJ, Tsuang MT, Lyons MJ. Genetics of verbal working memory processes: A twin study of middle-aged men. Neuropsychology. 2007;21(5):569–580. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.21.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremen WS, Thompson-Brenner H, Leung Y, Grant M, Franz CE, Eisen S, Jacobson KC, Boake C, Lyons MJ. Genes, environment, and time: The Vietnam Era Twin Study of Aging (VETSA) Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2006;9(6):1009–1022. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, Mosing MA, Henry JD, Troller JN, Lammel A, Ames D, Marton NG, Wright MJ, Sachdev PS. Genetic influences of five measures of processing speed and their covariation with general cogntive ability in the elderly: The Older Autrlian Twins Study. Behavior Genetics. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10519-011–9474-1. Online First. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak M. Neuropsychological assessment. Oxford University Press; USA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Luciano M, Posthuma D, Wright MJ, de Geus EJC, Smith GA, Geffen GM, et al. Perceptual speed does not cause intelligence, and intelligence does not cause perceptual speed. Biological Psychology. 2005;70(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciano M, Smith GA, Wright MJ, Geffen GM, Geffen LB, Martin NG. On the heritability of inspection time and its covariance with IQ: a twin study. Intelligence. 2001b;29(6):443–457. [Google Scholar]

- Luciano M, Wright MJ, Geffen GM, Geffen LB, Smith GA, Martin NG. A genetic investigation of the covariation among Inspection Time, Choice Reaction Time, and IQ subtest scores. Behavior Genetics. 2004a;34(1):41–50. doi: 10.1023/B:BEGE.0000009475.35287.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciano M, Wright MJ, Geffen GM, Geffen LB, Smith GA, Martin NG. Multivariate genetic analysis of cognitive abilities in an adolescent twin sample. Australian Journal of Psychology. 2004b;56(2):79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Luciano M, Wright MJ, Smith GA, Geffen GM, Geffen LB, Martin NG. Genetic covariance among measures of information processing speed, working memory, and IQ. Behavior Genetics. 2001a;31(6):581–592. doi: 10.1023/a:1013397428612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons MJ, York TP, Franz CE, Grant MD, Eaves LJ, Jacobson KC, Schaie KW, Panizzon MS, Boake C, Xian H, Toomey R, Eisen SA, Kremen WS. Genes Determine Stability and the Environment Determines Change in Cognitive Ability During 35 Years of Adulthood. Psychological Science. 2009;20(9):1146–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02425.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Goldsmith HH. Alternative common factor models for multivariate biometric analyses. Behavior Genetics. 1990;20:569–608. doi: 10.1007/BF01065873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Maes HH. Methodology for genetic studies of twins and families. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer AC, Spinath FM, Riemann R, Angleitner A, Borkenau P. Genetic and environmental influences on two measures of speed of information processing and their relation to psychometric intelligence: Evidence from the German observational study of adult twins. Intelligence. 2000;28(4):267–289. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo L, Sanchez-Juan P, de Koning I, Sleegers K, van Swieten J, Aulchenko Y, Oostra BA, van Duijn CM. The heritability of cognitive function in a young genetically isolated population. Genetic study of cognitive function. 2006:49. Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmusson X, Zonderman A, Kawas C, Resnick S. Effects of age and dementia on the Trail Making Test. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1998;12(2):169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Williamson A, Gunning-Dixon F, Head D, Acker JD. Neuroanatomical and cognitive correlates of adult age differences in acquisition of a perceptual-motor skill. Microscopy Research and Technique. 2000;51(1):85–93. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20001001)51:1<85::AID-JEMT9>3.0.CO;2-0. [Article] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan R, Wolfson D. Neuroanatomy and neuropathology: a clinical guide for neuropsychologists. Neuro Psychology Pr 1985 [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T. Relations between cognitive abilities and measures of executive functioning. Neuropsychology. 2005;19:532–545. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.4.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T, Atkinson T, Berish D. Executive functioning as a potential mediator of age-related cognitive decline in normal adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2003;132:566–594. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.132.4.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sponheim S, Jung R, Seidman L, Mesholam-Gately R, Manoach D, O’Leary D, Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Lauriello J, Schulz SC. Cognitive deficits in recent-onset and chronic schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan G, Carmelli D. Evidence for Genetic Mediation of Executive Control. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57(2):133. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.2.p133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlaner JE, Bolanovich DJ. Development of the Armed Forces Qualification Test and predecessor Army screening tests, 1946–1950. Washington, DC: Personnel Research Section, Department of the Army; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- van Ravenzwaaij D, Brown S, Wagenmakers EJ. An integrated perspective on the relation between response speed and intelligence. Cognition. 2011;119(3):381–393. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yochim B, Baldo J, Nelson A, Delis D. D-KEFS Trail Making Test performance in patients with lateral prefrontal cortex lesions. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2007;13(04):704–709. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]