Abstract

The liver is the major metabolic organ and is subjected to constant attacks from chronic viral infection, uptake of therapeutic drugs, life behavior (alcoholic), and environmental contaminants, all of which result in chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and ultimately, cancer. Therefore, there is an urgent need to discover effective therapeutic agents for the prevention and treatment of liver injury; the ideal drug being a naturally occurring biological inhibitor. Here, we establish the role of IL30 as a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine which can inhibit inflammation-induced liver injury. In contrast, IL27, which contains IL30 as a subunit, is not hepatoprotective. Interestingly, IL30 is induced by the pro-inflammatory signal such as IL12 through IFNγ/STAT1 signaling. In animal models, administration of IL30 via a gene therapy approach prevents and treats both IL12-, IFNγ-, and Concanavalin A -induced liver toxicity. Likewise, immunohistochemistry analysis of human tissue samples revealed that IL30 is highly expressed in hepatocytes yet barely expressed in inflammation-induced tissue such as fibrous/connective tissue. These novel observations reveal a novel role of IL30 as a therapeutic cytokine that suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokine-associated liver toxicity.

Keywords: IL12, IFNγ, IL27p28 (IL30), EBI3, TCCR, ConA

INTRODUCTION

The liver is the major metabolic organ and is constantly subjected to attacks such as chronic alcohol consumption, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and hepatitis virus. These attacks cause immune cell activation, which leads to inflammation, as well as continuous rounds of necrosis and regeneration of hepatocytes. Such conditions make a permissive environment for the development of fibrosis and cirrhosis and expansion/alteration of stem cell compartment, all conditions that fuel carcinogenesis (1). With the current rise of chronic hepatitis B and C infections and health care costs, new and effective therapeutic agents for the prevention and treatment of inflammation-related liver injury are needed (2).

Chronic inflammation in the liver has long been recognized as a trigger for chronic liver disease and, ultimately, a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cytokines and cytokine-induced inflammatory responses are the primary factors for controlling whether the liver undergoes effective repair and regeneration or degeneration, oncosis, and fibrosis (3, 4). For example, aberrant signaling of TGF-β and IL6 plays a role in cellular differentiation of hepatic progenitor/stem cells and hepatocellular carcinoma (4).

IL12 is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine required for the generation and maintenance of protective Th1 responses (5). Since sustained levels of expression of IL12 also induce cytotoxicity of the liver, IL12 is a strong candidate for analyzing cytokine-mediated liver pathology (6). The predominant mechanism associated with IL12 liver toxicity is considered to be IL-12-induced IFNγ (7, 8). High levels of IFNγ expression and the activation of the downstream transcription factor STAT1 have been observed in patients with inflammatory and autoimmune liver diseases, such as viral hepatitis and liver allograft rejection, and patients with cirrhosis (9–13). Moreover, mice lacking the IFNγ/STAT1 proinflammatory axis are protected against ConA-induced hepatotoxicity, while mice overexpressing IFNγ in the liver showed liver injury resembling that of chronic active hepatitis (13–15). Therefore, IL12- and IFNγ– induced hepatotoxicity may serve as valuable models for discovering anti-inflammation therapeutics.

IL27, a member of IL12 family, has a potential protective role against liver disease since this cytokine plays an anti-inflammatory role in many autoimmune disease models such as autoimmune encephalomyelitis or collagen-induced arthritis (16, 17). IL27 downregulates the immune response by inhibiting IL2 and IL17A expression while enhancing production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL10 (18–22). Meanwhile, the role of IL27 or its subunits on liver toxicity is not clear in the literature (23, 24). The understanding of IL27 was further complicated by a study showing that the IL27 subunit p28 possesses a similar function as IL27 as it also inhibited IL17 induction, albeit at a much lower level when compared to IL27 (25). Thus, from a therapeutic standpoint, the current understanding of p28 in the literature is that this subunit is less attractive than IL27 in modulating anti-inflammatory conditions. In summary, the role of IL27 and its subunits as therapeutic agents in liver disease is controversial, and a large need remains to identify natural inhibitors existing in the human body that play an anti-inflammatory role for preventing or treating inflammatory cytokine-induced liver injury.

In this study, we discover that IL27p28 (referred as IL30 throughout the manuscript) inhibits IL12-, IFNγ-, and ConA-mediated hepatotoxicity via suppression of endogenous IFNγ expression, independently of IL27 or the IL27 receptor WSX1 (TCCR). These novel observations suggest that IL30 is a naturally occurring inhibitor of inflammation and far more potent than IL27 as a therapeutic candidate in inhibition of liver toxicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal procedures

All animal procedures were approved by the IACUC. Six- to eight-week-old Balb/C, C3H, C3H STAT1−/− mice, C57bl/6, EBI3−/−, and WSX (TCCR)1−/− mice were used for this study. Using the protocols described previously, cytokine-encoding and control plasmid DNA (a total of 10 μg per mouse and 5 μg per muscle in a volume of 30 μl per muscle) were injected into two separate hind limb tibialis muscles via electroporation (first treatment), in the front limbs (second treatment), or back into the hind limb tibialis muscle for the third treatment (26). Mice received treatments 5 days apart. For mice receiving a combination of treatments, equal amount of plasmids were mixed prior to injection. Five days after the second treatment, mice were sacrificed and both serum and livers were obtained. IL30 (R&D systems) and IFNγ (eBioscience) expression in the serum were analyzed via ELISA.

Hematoxylin-eosin staining of liver sections and scoring of liver lesions

Sections of paraffin-embedded tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and the lesions were counted under a 200X microscope, where 15 fields per slide were counted. Images are taken using a light-inverted Olympus microscope (Center Valley, PA). The small lesions typically induced in the liver by pIL12 DNA treatments (referred as typical lesions throughout the manuscript) consist of hepatocellular degeneration and hepatocyte necrosis along with Kupffer cell hyperplasia attended by small number of lymphocytes. The larger necrotic lesions were characterized by massive death of hepatocytes in the liver. The scoring was confirmed by an independent “blinded” observer.

Detailed Materials and Methods can be found on Supplemental Information.

RESULTS

IL12 gene therapy induces hepatotoxicity

IL12 is one of the primary inflammatory cytokines, and it is known that administration of recombinant IL12 protein induces liver toxicity (6). Electroporation-mediated delivery of IL12-encoding DNA (pIL12) rather than delivery of the recombinant protein has several advantages such as inducing systemic production of the cytokine over time, thereby better mimicking the pro-inflammatory environment during liver pathogenesis. To establish an in-vivo model to study cytokine-mediated liver toxicity via gene therapy, pIL12 was administered into muscles followed by electroporation (27).

Robust expression of IL12 and IFNγ protein were detected in the blood (Fig. 1A, 1B), suggesting that IL12 is biologically functional. Since both IL12 and IFNγ enhance liver toxicity, we determined whether systemic introduction of IL12 DNA via electroporation induced liver toxicity. Liver histology confirmed that delivery of pIL12 but not control DNA induced typical lesions of IL12-induced hepatotoxicity (Fig. 1C). These lesions were mainly seen in the liver but not in other major organs (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Delivery of IL12 via gene therapy induces toxicity in the liver in vivo.(A, B) IL12-or control-encoding plasmid DNA was administered into Balb/c mice (n=4) via intramuscular injection followed by electric pulses to enhance the DNA uptake by muscle cells. Expression of IL12 (A) or IFNγ (B) in the serum was determined on the indicated days after the administration (n= 4–8). (C) Histological analysis of hematoxylin and eosin staining of paraffin-embedded formalin-fixed liver tissue of mice treated with either IL12- or control-encoding plasmid DNA.

IL12 induces IL30 expression in vitro and in vivo via an IFNγ-dependent mechanism

Since infection- or pro-inflammatory cytokine-induced liver toxicity is resolved over time after initial injury, we hypothesized that the recovery is due to induction of naturally occurring key inhibitors against pro-inflammatory cytokines. Indeed, others have shown previously that an anti-inflammatory cytokine such as IL10 is required during liver regeneration (28). Using microarrays, we identified that IL12 induces IL30, the p28 subunit of IL27, but does not induce the expression of EBI3, the other subunit of IL27 (unpublished data). Indeed, IL12 gene therapy induced IL30 at a maximum level of 200 pg/mL on day 8 (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Induction of the IL27 subunit IL30 expression via IL12 is mediated through IFNγ. (A) Detection of IL30 expression by ELISA in serum of mice treated with either IL12- or control-encoding plasmid DNA administered into Balb/c mice (n=4). (B–D) Detection of IL30 expression via treatment with either rIL12 or rIFNγ in splenocytes (n=3) isolated from wildtype (B), IFNγ−/− (C), and IFNγR−/− mice (D). (E, F) Detection of IL30 expression by ELISA in serum of mice treated with either IL12- (E) or IFNγ-encoding plasmid DNA (F) administered into wildtype or STAT1−/− mice (n=2–3).

To determine the primary cell source from which IL30 was induced by IL12, B cells, macrophages, dendritic (DC), monocytes, and T cells were tested because the former 3 types of cells are known sources for IL27 production while the T cells were used as a negative control (29). Irrespective of the cell types, no pronounced induction of IL30 by IL12 treatment was found in any of the cells (Supplemental Fig. 2A), suggesting an intermediate molecule. Since IFNγ is the primary IL12-induced cytokine, and a recent study showed IFNγ induces IL30 expression in macrophages in vitro (5, 30), we tested whether IFNγ acts as an IL12-effector cytokine for inducing IL30 expression. Notably, rIFNγ treatment induces a high level of IL30 in DC and macrophages cells (Supplemental Fig. 2B). These results indicates that induction of IL30 by IL12 requires the initial induction of IFNγ by IL12 from IFNγ-producing cells, and the induced IFNγ then upregulates IL30 from the known IL30-producing cells, such as DC. To confirm this hypothesis, spleen cells were used to detect the direct induction with rIL12 because spleen cells should contain both IFNγ and IL30 producing cells. Different from treatment of individual type of cells, treatment of this cell mixture with rIL12 induced IL30 (Fig. 2B). To test whether IFNγ is the only IL12-dependent inducer of IL30, splenocytes deficient in IFNγ or IFNγ R were treated with rIL12 or rIFNγ. As expected, rIL12 induces IL30 expression in wildtype splenocytes (Fig. 2B) but not in splenocytes deficient in either IFNγ or IFNγR (Fig. 2C, 2D). These results suggest that IFNγ is the sole IL12-induced effector protein that induces IL30.

Induction of IL30 is highly dependent on the distal STAT1 binding site ‘a’

STAT1 is important transcription factor downstream of IFNγ and plays a critical role in liver pathology (5, 13). Indeed, STAT1 plays a critical role in our model, systemic expression of either IL12 or IFNγ induces IL30 expression in wildtype mice but not in STAT1 deficient mice (Fig. 2E, 2F).

Our in vivo results strongly conclude that STAT1 dictates IL30 induction by IL12 or IFNγ (Fig. 2E, 2F), and is in disagreement from the in vitro results by Liu et al (2007)’ observation that induction of IL30 is dependent on IRF1. One known mechanism could explain this discrepancy: STAT1 activates IRF1 and this activation counts for inducing the IL30 expression in vitro and in vivo as found by Liu et al (2007) and us (Fig. 2E, 2F) (31). To support this explanation, it is important to exclude the role of STAT1 in directly activating IL30 promoter activity. However, a genomic blast search identified three putative STAT1 binding sites—gamma-activating sequences (GAS) in the IL30 promoter located at ~4.3, 1.3 and 1.1 kb upstream of the transcription starting site. To determine whether rIFNγ treatment induces IL30 promoter activity via STAT1 binding on these putative STAT1 binding sites, two IL30 promoters, one with and the other without the distal STAT1 binding site ‘a’, were generated (Supplemental Fig. 2C). Deletion of site ‘a’ almost completely impairs the activation of gene transcription, while deletion of site ‘b’ does not affect such transcription (Supplemental Fig. 2D, 2E) which implies that the distal binding site ‘a’ but not ‘b’ is critical to induce IL30.

Liver cells regulate the magnitude of induction of IFNγ and IL30

Previous research shows that IL12-mediated hepatocyte necrosis was mainly dependent on IFNγ expression (7); therefore, we measured IFNγ expression both in the liver and the spleen following IL12 treatment in vivo. Five days after the second treatment, both the spleens and livers were examined by quantitative real-time PCR. While the expression of IFNγ in the spleens of mice treated with IL12 was at comparable levels as the control treatment, IFNγ expression in the liver was 40-fold higher when mice were treated with pIL12 as compared to the control treatment (Fig. 3A). Likewise, the level of IL30 expression was highly upregulated in the liver by IL12 (~14-fold) but not in the spleen (Fig. 3B). The level of the IL27 subunit EBI3 expression was barely upregulated in either the liver or the spleen, with less than a 2–fold increase (Fig. 3C), suggesting that IL30 but not IL27 might play a role in hepatotoxicity.

Fig. 3.

Systemic IL12 therapy affects gene expression in the liver. (A–C) The livers and spleens of mice treated with either IL12- or control-encoding plasmid DNA were collected 5 days after the second treatment and analyzed for IFNγ (A), IL30 (B), or EBI3 (C) via quantitative real-time PCR analysis. Values are expressed as fold changes compared to the control treatment. (D) The expression of IFNγ in splenocytes in the presence or absence of hepatocytes on the indicated days (n=3). (E) The expression of IL30 in splenocytes in the presence or absence of hepatocytes on the indicated days (n=3). *, P<0.05, for comparisons between treatments indicated by horizontal lines. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

As IL30 expression is primarily upregulated in the liver (Fig. 3B), we inquired whether hepatocytes play a role in IL12-mediated IFNγ expression in immune cells. To test this working hypothesis, hepatocytes, splenocytes, or a mixture of these cells were incubated in the presence or absence of rIL12. After incubation for 24 hours, only the presence of hepatocytes in the splenocytes but not splenocytes alone caused a robust induction of IFNγ by IL12 (Fig. 3D). By day 4, this boosting effect by hepatocytes was still significant but not as pronounced as in day 1.

As the presence of liver cells enhances expression of IFNγ in splenocytes, we tested whether hepatocytes also aided the induction of IL30. As expected, by day 1 there is a ~2-fold increase in presence IL30 in presence of hepatocytes and by day 4, this difference was significantly enhanced (Fig. 3E). The kinetics of expression of IL30, which is similar to induction of other anti-inflammatory cytokines and requires a lag period response to primary inflammatory stimulus, and the fact that hepatocytes significantly aid the expression of this cytokine suggest that IL30 has a function in liver biology and perhaps it might aid in liver repair.

IL30 inhibits IL12-mediated hepatotoxicity

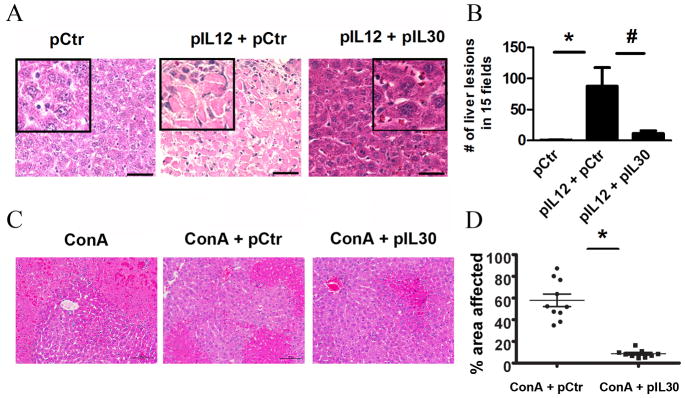

The results described above indicate that pIL12 primarily boosts the induction of IL30 expression but not EBI3 in livers which leads to the next question: Is IL30 a promoter or inhibitor in IL12/IFNγ induced liver injury? To test the role of IL30, mice were treated via electroporation with multiple administrations (3 times) of a toxic dose of pIL12 (20 μg of DNA per mouse) in the presence or absence of pIL30. Notably, systemic treatment with such high levels of pIL12 resulted in enhanced toxicity over a longer period of time (even 20 days after the last administration). To our surprise, co-administration of pIL12 and IL30 significantly inhibited the number of lesions in the liver when compared to pIL12 treatment (Fig. 4A, 4B).

Fig. 4.

IL30 inhibits IL12-mediated toxicity. (A, B) Photomicrograph analysis of livers of mice treated with control, a mixture of control and IL12-, or IL12- and IL30-encoding plasmid DNA delivered via electroporation were collected ten days after the third treatment (A), and the number of lesions in the liver in a total of fifteen fields were counted (B) (n= 8–10). Data represents at least three independent experiments in three independent mouse models. *, #, P<0.05, for comparisons between treatments indicated by horizontal lines. Line, 50 μm. (C, D) Representative liver photomicrographs of mice treated with ConA (20 mg/kg) in the presence of control or IL30-encoding plasmids via gene therapy (C) (n=10) and the percentage of area affected on the micrographs was quantified using Nikon NIS Elements automated analysis software (D).

To confirm this observation in a conventional inflammation-induced liver injury model, we have used the well-established ConA model to understand the role of IL30 in acute liver toxicity. Hepatic injury via ConA was significantly reduced once mice were treated via IL30 gene therapy (Fig. 4C, 4D). The reduced injury is associated with the robust expression of IL30 in the serum (Supplementary Fig. 3). This observation suggests that IL30 is a potent inhibitor of pro-inflammatory cytokine-induced liver toxicity.

IL30 inhibits the toxicity of the liver independently of IL27 or WSX1

Others have previously shown that IL30 has a similar yet not as effective function as IL27 (19). To determine whether IL30 requires the other subunit, EBI3, to form a heterodimer for maximizing inhibition of IL12 toxicity, we compared the efficacy of IL30 to either EBI3 or IL27. Interestingly, IL30 is more potent than IL27 or EBI3 in inhibiting IL12-induced toxicity in the liver, including the reduction of the number of liver lesions (Fig. 5A, 5B) and ALT/AST levels (Supplemental Fig. 4), suggesting that IL30 may act independently of IL27. To further this hypothesis, we used EBI3 knockout (EBI3−/−) mice. As expected, IL30 reverses IL12 hepatotoxicity in EBI3−/− mice, while reconstitution of IL27 or overexpression of EBI3 does not affect liver toxicity (Fig. 5A–B).

Fig. 5.

IL30 inhibits the toxicity of the liver independently of IL27 or WSX1. (A–B) Histological examination of livers of mice treated with a mixture of control and IL12-, IL30- and IL12-, EBI3- and IL12-, or IL27- and IL12-encoding plasmid DNA delivered via electroporation. Livers were collected five days after the second treatment in either wildtype (WT) mice (A, upper panel), EBI3−/− mice (A, middle panel), or WSX1−/− mice (A, lower panel), and the number of lesions in the liver in a total of fifteen fields were counted (B) (n=3). Data represents at least two independent experiments. #, P<0.05, comparison of each treatment group to pIL12+pCtr group within each strain. Line, 50 μm.

One potential mechanism that explains the protective role of IL30 in the absence of EBI3 could be that IL30 competes or is more efficient than IL27 in occupying WSX1, therefore initiating downstream signaling independently of IL27. To confirm this hypothesis, the effect of IL30 on IL12-mediated toxicity was tested in WSX1−/− mice. If IL30 signals through WSX1 and competes with IL27 for signaling, than the lack of WSX1 would demolish the ability of IL30 to inhibit liver toxicity. The same as found in wildtype mice, IL30 inhibits the number of liver lesions and the amount of the liver transaminases released in the serum in WSX1−/− mice (Fig. 5A, 5B, Supplemental Fig. 4). These results confirm that hepatoprotective role of IL30 is independent of IL27 pathway.

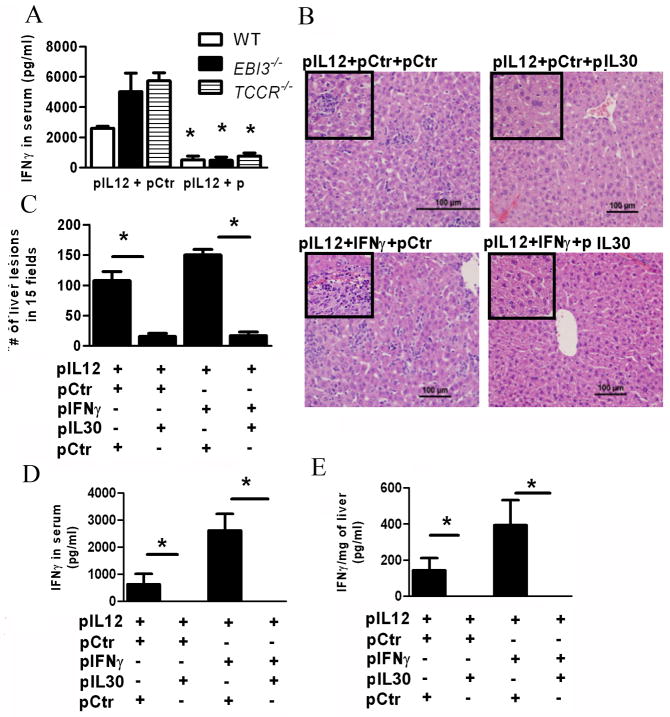

IL30 inhibits hepatotoxicity via reduction of circulating IFNγ

Since IL12 induces IL30 expression via IFNγ, then we asked whether IL30 might inhibit IL12 toxicity via inhibition of IFNγ expression. As such, we determined whether IL30 inhibits IL12-mediated IFNγ expression in wildtype, EBI3−/−, and WSX1−/− mice. Expectedly, IL30 inhibits circulating IFNγ levels (Fig. 6A). This observation once more confirms the IL27- and WSX1-independent function of IL30.

Fig. 6.

IL30 inhibits the toxicity of the liver via reduction of circulating IFNγ through a negative feedback mechanism. (A) Analysis of IFNγ expressed in serum via ELISA of mice treated with a mixture of control and IL12- or IL30- and IL12-encoding plasmid DNA delivered via electroporation. Serum was collected five days after the second treatment in either WT, EBI3−/−, or WSX1−/− mice (A) *, P<0.05, significant difference between comparison within strain. (B–E) Histological analysis (B), counts of typical IL12-mediated liver lesions in a total of fifteen fields (C). Detection of IFNγ expression in the serum (D) or in the liver (E) of mice treated with 12μg of a mixture of equal amounts of plasmids as indicated each panel Fig.. (n=3) Data represents at least two independent experiments. (B–E) *, P<0.05, for comparisons between treatments indicated by horizontal lines.

Of interest here is that the number of lesions induced by IL12 is lower in the EBI3−/− and WSX1−/− when compared to wildtype mice (Fig. 5B), though the level of IL12-mediated IFNγ induction is heightened in the absence of WSX1 or EBI3. This discrepancy could be explained by the increased induction of IL30 in these mice (Supplementary Fig. 5), which counteracts the toxic effect from increased IFNγ and reduces toxicity in livers.

To further confirm that IFNγ plays a key role in IL12-mediated liver injury and IL30 inhibits IFNγ expression; both pro-inflammatory cytokines were co-administered into mice. As expected, co-administration of IL12 and IFNγ enhanced toxicity of the liver when compared to IL12 alone (Fig. 6B, 6C), further demonstrating IFNγ’s role in hepatotoxicity. Meanwhile, the addition of IL30 significantly reduced the number of lesions in the liver (Fig. 6C). Notably, co-administration of IL12 and IFNγ markedly increased the large necrotic areas (characterized by hepatocyte degeneration and surrounded by lymphocytes) in the liver when compared to IL12 alone, while administration of IL30 remarkably inhibited toxicity of the liver, with no apparent large necrotic areas visible (Supplemental Fig. 6A, 6B). To exclusively determine that IL30 inhibits IFNγ expression, the levels of IFNγ in the blood and in the liver were measured. While co-administration of IL12 and IFNγ induced higher levels of IFNγ in both the serum and the liver, the presence of IL30 resulted in no detectable IFNγ in either serum or liver (Fig. 6D, 6E). These results advocate that IL30 is a potent inhibitor of IFNγ expression and IL12- and IFNγ-mediated liver toxicity.

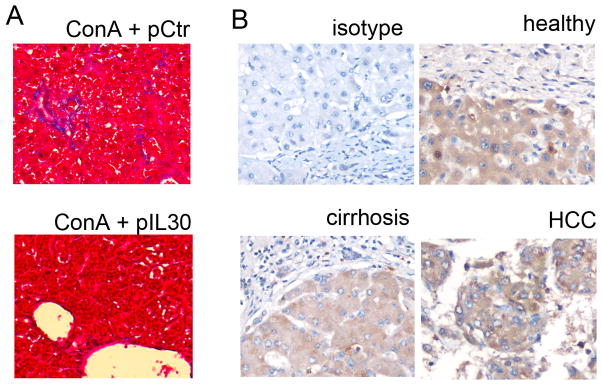

IL30 is a potential therapeutic agent against hepatotoxicity

The preventive role of IL30 against IL12-induced toxicity described above encouraged us to study whether IL30 also has a therapeutic potential to repair the liver injury once initiated. In this regard, IL30 was administered 2 days after the IL12 treatment and liver toxicity was determined. Two independent methods of gene delivery, electroporation and hydrodynamic delivery showed that IL30 administration post-injury heals liver injury and reduces the level of toxic IFNγ expression (Fig. 7A, 7B). Because chronic inflammation causes liver fibrogenesis, the effect of IL30 was also assessed on hepatic fibrosis during chronic administration of ConA. Treatment with IL30 via gene therapy reduced collagen depositions (Mason’s Trichrome staining) (Fig. 8A).

Fig. 7.

Therapeutic application of IL30 post-injury. (A–B) Histological analysis of liver (A) and IFNγ expression in serum (B) of mice (n=3) treated with IL12-encoding plasmid DNA followed by a second treatment of control or IL30-encoding plasmid DNA delivered via electroporation (EP) or hydrodynamic delivery (HD) two days after the first treatment. Livers and serum were collected 5 days after the second treatment. *, P<0.05, for comparisons between treatments indicated by horizontal lines.

Fig. 8.

Representative microphotographs Mason’s Trichrome Staining (A) of fixed-liver specimens in a chronic ConA model treated with control or IL30-encoding plasmid (n=10). Representative microphotographs of IL30 characterization via immunostaining in fixed-liver tissue derived from healthy, cirrhosis, or hepatocellular carcinoma affected patients (B) (n=7).

Such data reveals that IL30 has therapeutic potential in a clinical setting to reduce liver pathology. To determine how IL30 reduces toxic IFNγ expression, we determined the transcriptional activity of IL-12-induced IFNγ in the presence or absence of IL30 over time. Two days after the first treatment, IL30 raise IFNγ levels, but 5 days after the second treatment, IL30 reduced these levels by 10-fold (Supplemental Fig. 7). IL30 does not affect the ability of IL12 to produce IFNγ, nor does it affect CMV-promoter driven of IL12 or IFNγ expression (Supplemental Fig. 8A–C), but instead disrupts constitutive IFNγ expression once it’s initiated possibly post-translationally.

To better characterize the cellular source of IL30 in the liver, specimens from patients (with or without disease) were stained via immunohistochemistry. Interestingly, and never reported before, in normal patients IL30 is highly expressed in the hepatocytes, while the levels of expression are lower in the fibrous/connective tissue, further suggesting a protective role of IL30 (Fig. 8B). Though the staining intensity between normal hepatocyte, cirrhosis, and HCC are similar (Fig. 8B), the data reported in reference 34 (Supplemental Fig. 9) shows that IL30 mRNA levels were lower in patients with liver disease (HCC, dysplasia, or cirrhosis) than in healthy livers. The discordance between immunostaining and mRNA detection among patients is associated with the absolute tissue area that expresses IL30. In other words, a larger area of connective/stroma tissues is often found in patients with liver diseases, which have extremely low levels of IL30 expression and, therefore, a low level of IL30 mRNA is detected per tissue weight when compared to healthy ones.

DISCUSSION

IL12 is a key candidate for treating malignancies since it is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine, activates T and NK cells, and induces the expression of IFNγ expression. Although promising in treatment of malignancies, especially micrometastic lesions, high toxicity and fatalities were observed in clinical trials mainly due to IFNγ expression. Therefore, control of excessive induction of IFNγ may be achieved by using gene therapy instead of acute dose of recombinant IL12 therapy. Even with gene therapy, a high dose and frequent administrations could trigger liver toxicity; however, IL12-induced toxicity can be prevented or even treated by using IL30 as we discovered in this study. This observation may be translated to human clinics for safely using IL12 or other pro-inflammatory cytokine therapy. This conclusion was further supported by the fact that IL30 significantly reduces the ConA-induced liver injury as reported in this study is also in agreement with the fact that ConA causes less toxicity in EBI3 KO mice than in wild type mice (23, 24). Importantly, multiple lines of evidence from our study suggest that IL30, as an independent cytokine, inhibits IL12-induced liver injury due to the independence of IL27 and EBI3 signaling pathways. This unique discovery reveals that IL30 perhaps is an important therapeutic candidate for preventing not only IL12 and IFNγ but other inflammatory cytokine-induced liver toxicity.

IFNγ plays a crucial role not only in initiating innate and adaptive immune responses but also in homeostatic functions that limit inflammation-associated tissue destruction. IFNγ initiation of an adaptive immune response is well understood and occurs mainly via activation of macrophages and immune cells at the site of inflammation; however, how IFNγ maintains a crucial role in homeostatic functions is not fully understood. Since IFNγ administration at the site of the inflammation exacerbates diseases in arthritis and autoimmune diabetes models yet a lack of IFNγ seems to enhance the severity of arthritis in the K/B×N model (32), IFNγ is a key mediator for upregulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines, which are necessary to decrease tissue destruction. So, understanding which particular molecules are signaling downstream of IFNγ has important therapeutic implications. Our study not only confirms that IFNγ induces IL30 in vitro but also reveals the biological function of this cytokine. Different from Liu et al (2007) that established IFNγ induces IL30 in macrophages in vitro, we found that IL30 is a very potent inhibitor of pro-inflammatory cytokine-induced hepatotoxicity in vivo. Revealing the role of IL30 and establishing the association between IFNγ and IL30 illustrates how a pro-inflammatory cytokine such as IFNγ can control inflammation-induced tissue injury via a negative feedback mechanism in a natural biological system.

Our discovery that IL30 is a liver injury inhibitor bodes well with published results from IL27R−/− and EBI3−/− mice in a hepatitis model (23, 24). In a ConA model of hepatitis, lack of IL27 signaling (IL27R−/−) showed an exacerbated response, while EBI3−/− are protected from ConA induced hepatitis when compared to wildtype mice. Based upon our results, the reduced toxicity from ConA in EBI3 −/− is perhaps due to increased IL30 resulting from a lack of EBI3 available to engage and form IL27. Indeed, exogenous introduction of IL30 plasmids via gene therapy significantly reduced ConA-induced hepatotoxicity.

Multiple lines of evidence from this study point out to IL30 inhibition of liver toxicity independently of IL27. First, IL30 inhibits liver toxicity and IFNγ in EBI3−/− or WSX1−/− mice, and, second, reconstitution of either EBI3 or IL27 in EBI3−/− mice does not ameliorate liver toxicity. A previous study showed that IL30 binds to cytokines other than EBI3 to form an IL30/cytokine-like factor 1 complex (IL30/CLF), suggesting that IL30/CLF inhibits liver toxicity (33). The plausibility of this theory is questionable as IL30/CLF needs WSX1 receptor to signal, whereas in our study IL30 can inhibit liver toxicity even in the absence of WSX1. Moreover, in our model, IL12 mainly induces the transcription of IL30 and not EBI3. Of course, one possible argument is that the endogenous levels of EBI3 might be very high and induction of IL30 by IFNγ results in the generation of IL27 that inhibits liver toxicity. This explanation is unlikely as even in EBI3−/− and TCCR−/− mice, IL30 lowers hepatotoxicity.

In summary, this study of IL30 reveals its novel function: inhibition of IL12/ConA-mediated liver injury, which occurs independently of both IL27 and WSX1 by preventing IFNγ expression in the liver and circulating IFNγ in the serum.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Fig. 1 Histological analysis of hematoxylin and eosin staining of paraffin-embedded formalin-fixed tissue of different organs in mice treated with either IL12- or control-encoding plasmid DNA.

Supplemental Fig. 2. Induction of the IL27 subunit IL30 expression via IL12 is mediated through IFNγ and STAT1 binding site ‘a’. (A, B) Induction of IL30 by recombinant IL12 protein (rIL12) (A) and rIFNγ (B) in different cell types (n=3). BMDM, BMDC, SL12.4, and TIB220 represent bone marrow derived macrophages, dendritic cells, naïve T cells, and hybridoma B cells, respectively. (C) Structure of IL30 promoter-luciferase gene constructs and the locations of STAT1 binding sites. (D, E) IL30 promoter activities with and without STAT1 binding site ‘a’ (D) or STAT1 binding site ‘b’(E) in the presence and absence of rIFNγ treatment. Luciferase activity was used to determine the transcriptional activity of the IL30 promoter (n=3). (B, D, E) *, P<0.05, for comparisons between treatments indicated by horizontal lines.

Supplemental Fig. 3. Gene therapy induces robust expression of IL30. Mice were treated with control or IL30-encoding plasmids followed by electroporation, and IL30 expression was determined in the serum via ELISA.

Supplemental Fig. 4. IL30 inhibits the toxicity of the liver independently of IL27 or WSX1. The levels of expression of alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) in the serum of mice treated with a mixture of control and IL12-, IL30- and IL12-, EBI3- and IL12-, or IL27- and IL12-encoding plasmid DNA delivered via electroporation were measured. *, P<0.01, #, P<0.05, comparison of each treatment group to pIL12+pCtr group.

Supplemental Fig. 5. Analysis of IL30 expressed in serum via ELISA of mice treated with a mixture of control and IL12 -encoding plasmid DNA delivered via electroporation either wildtype, EBI3−/−, or WSX1−/− mice. Serum was collected five days after the second treatment.

Supplemental Fig. 6. IL30 inhibits liver necrosis. Histological analysis (A), counts of necrotic areas in a total of fifteen fields (B) of mice treated with 12 μg of a mixture of equal amounts of plasmids as indicated in each panel. *, P<0.05, for comparisons between treatments indicated by horizontal lines.

Supplemental Fig. 7. The livers and spleens of mice treated with a mixture of equal amounts of plasmids as indicated in each panel (n=2) were collected at day 2 after the first treatment (upper panels) or day 5 after the second treatment (lower panels) and analyzed for IFNγ expression via quantitative real-time PCR analysis. Values are expressed as fold changes compared to control treatment. Data represents at least two independent experiments.

Supplemental Fig. 8. IL30 plasmid does not affect CMV-promoter driven expression of IL12 or IFNγ. Cells were co-transfected with the plasmids as indicated in the figure, (B) and IL12 (A), IFNγ (B), and IL30 (C) expression in the supernatant was measured via ELISA (n=3).

Supplemental Fig. 9. Comparison of IL30 expression in the liver of healthy patients or patients with liver cirrhosis, dysplasia, or hepatocellular carcinoma (early and advanced stage) from the data set derived from reference (34).

Acknowledgments

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: This research is supported in part by NIH grant RO1 CA098928.

WSX1−/− cells was derived from WSX1−/− mice from Genetech, Inc. with assistance from Frederic J de Sauvage. Authors are also thankful to Shiguo Zhu for performing some of the DNA administration and serum collection. Special thanks go to Sherry Ring for embedding the paraffin section and preparing liver slides, Blake Johnson who performed the hydrodynamic delivery, and to Scott Reed, a pathologist, who helped interpret data, read slides, and had a critical input during manuscript preparation.

LIST of ABBREVIATIONS

- IL

interleukin

- EBI3

Epstein-Barr virus induced gene 3

- STAT1

signal transducer and activator of transcription 1

- IFNγ

interferon gamma

- DC

dendritic cells

- ConA

Concanavalin A

- ALT

alanine transaminase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- TCCR

T-cell cytokine receptor

References

- 1.Farazi PA, DePinho RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:674–687. doi: 10.1038/nrc1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mishra L. Health care reform: how personalized medicine could help bundling of care for liver diseases. Hepatology. 53:379–381. doi: 10.1002/hep.24144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parola M, Pinzani M. Hepatic wound repair. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2009;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang Y, Kitisin K, Jogunoori W, Li C, Deng CX, Mueller SC, Ressom HW, et al. Progenitor/stem cells give rise to liver cancer due to aberrant TGF-beta and IL-6 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2445–2450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705395105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:133–146. doi: 10.1038/nri1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Galan MC, Reynolds D, Correa SG, Iribarren P, Watanabe M, Young HA. Coexpression of IL-18 strongly attenuates IL-12-induced systemic toxicity through a rapid induction of IL-10 without affecting its antitumor capacity. J Immunol. 2009;183:740–748. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryffel B. Interleukin-12: role of interferon-gamma in IL-12 adverse effects. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;83:18–20. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.4306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kusters S, Gantner F, Kunstle G, Tiegs G. Interferon gamma plays a critical role in T cell-dependent liver injury in mice initiated by concanavalin A. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:462–471. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8690213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arai K, Liu ZX, Lane T, Dennert G. IP-10 and Mig facilitate accumulation of T cells in the virus-infected liver. Cell Immunol. 2002;219:48–56. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(02)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harvey CE, Post JJ, Palladinetti P, Freeman AJ, Ffrench RA, Kumar RK, Marinos G, et al. Expression of the chemokine IP-10 (CXCL10) by hepatocytes in chronic hepatitis C virus infection correlates with histological severity and lobular inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:360–369. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0303093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mihm S, Schweyer S, Ramadori G. Expression of the chemokine IP-10 correlates with the accumulation of hepatic IFN-gamma and IL-18 mRNA in chronic hepatitis C but not in hepatitis B. J Med Virol. 2003;70:562–570. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tagawa Y, Sekikawa K, Iwakura Y. Suppression of concanavalin A-induced hepatitis in IFN-gamma(−/−) mice, but not in TNF-alpha(−/−) mice: role for IFN-gamma in activating apoptosis of hepatocytes. J Immunol. 1997;159:1418–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong F, Jaruga B, Kim WH, Radaeva S, El-Assal ON, Tian Z, Nguyen VA, et al. Opposing roles of STAT1 and STAT3 in T cell-mediated hepatitis: regulation by SOCS. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1503–1513. doi: 10.1172/JCI15841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toyonaga T, Hino O, Sugai S, Wakasugi S, Abe K, Shichiri M, Yamamura K. Chronic active hepatitis in transgenic mice expressing interferon-gamma in the liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:614–618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radaeva S, Jaruga B, Kim WH, Heller T, Liang TJ, Gao B. Interferon-gamma inhibits interferon-alpha signalling in hepatic cells: evidence for the involvement of STAT1 induction and hyperexpression of STAT1 in chronic hepatitis C. Biochem J. 2004;379:199–208. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niedbala W, Cai B, Wei X, Patakas A, Leung BP, McInnes IB, Liew FY. Interleukin 27 attenuates collagen-induced arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1474–1479. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.083360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batten M, Li J, Yi S, Kljavin NM, Danilenko DM, Lucas S, Lee J, et al. Interleukin 27 limits autoimmune encephalomyelitis by suppressing the development of interleukin 17-producing T cells. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:929–936. doi: 10.1038/ni1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzgerald DC, Zhang GX, El-Behi M, Fonseca-Kelly Z, Li H, Yu S, Saris CJ, et al. Suppression of autoimmune inflammation of the central nervous system by interleukin 10 secreted by interleukin 27-stimulated T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1372–1379. doi: 10.1038/ni1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stumhofer JS, Silver JS, Laurence A, Porrett PM, Harris TH, Turka LA, Ernst M, et al. Interleukins 27 and 6 induce STAT3-mediated T cell production of interleukin 10. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1363–1371. doi: 10.1038/ni1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villarino A, Hibbert L, Lieberman L, Wilson E, Mak T, Yoshida H, Kastelein RA, et al. The IL-27R (WSX-1) is required to suppress T cell hyperactivity during infection. Immunity. 2003;19:645–655. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00300-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Owaki T, Asakawa M, Kamiya S, Takeda K, Fukai F, Mizuguchi J, Yoshimoto T. IL-27 suppresses CD28-mediated [correction of medicated] IL-2 production through suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. J Immunol. 2006;176:2773–2780. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villarino AV, Stumhofer JS, Saris CJ, Kastelein RA, de Sauvage FJ, Hunter CA. IL-27 limits IL-2 production during Th1 differentiation. J Immunol. 2006;176:237–247. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siebler J, Wirtz S, Frenzel C, Schuchmann M, Lohse AW, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Cutting edge: a key pathogenic role of IL-27 in T cell- mediated hepatitis. J Immunol. 2008;180:30–33. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamanaka A, Hamano S, Miyazaki Y, Ishii K, Takeda A, Mak TW, Himeno K, et al. Hyperproduction of proinflammatory cytokines by WSX-1-deficient NKT cells in concanavalin A-induced hepatitis. J Immunol. 2004;172:3590–3596. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stumhofer JS, Laurence A, Wilson EH, Huang E, Tato CM, Johnson LM, Villarino AV, et al. Interleukin 27 negatively regulates the development of interleukin 17-producing T helper cells during chronic inflammation of the central nervous system. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:937–945. doi: 10.1038/ni1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li S, Xia X, Zhang X, Suen J. Regression of tumors by IFN-alpha electroporation gene therapy and analysis of the responsible genes by cDNA array. Gene Ther. 2002;9:390–397. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li S, Zhang X, Xia X, Zhou L, Breau R, Suen J, Hanna E. Intramuscular electroporation delivery of IFN-alpha gene therapy for inhibition of tumor growth located at a distant site. Gene Ther. 2001;8:400–407. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berg DJ, Kuhn R, Rajewsky K, Muller W, Menon S, Davidson N, Grunig G, et al. Interleukin-10 is a central regulator of the response to LPS in murine models of endotoxic shock and the Shwartzman reaction but not endotoxin tolerance. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2339–2347. doi: 10.1172/JCI118290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pflanz S, Timans JC, Cheung J, Rosales R, Kanzler H, Gilbert J, Hibbert L, et al. IL-27, a heterodimeric cytokine composed of EBI3 and p28 protein, induces proliferation of naive CD4(+) T cells. Immunity. 2002;16:779–790. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00324-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu J, Guan X, Ma X. Regulation of IL-27 p28 gene expression in macrophages through MyD88- and interferon-gamma-mediated pathways. J Exp Med. 2007;204:141–152. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Leung S, Qureshi S, Darnell JE, Jr, Stark GR. Formation of STAT1-STAT2 heterodimers and their role in the activation of IRF-1 gene transcription by interferon-alpha. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5790–5794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu HJ, Sawaya H, Binstadt B, Brickelmaier M, Blasius A, Gorelik L, Mahmood U, et al. Inflammatory arthritis can be reined in by CpG-induced DC-NK cell cross talk. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1911–1922. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crabe S, Guay-Giroux A, Tormo AJ, Duluc D, Lissilaa R, Guilhot F, Mavoungou-Bigouagou U, et al. The IL-27 p28 subunit binds cytokine-like factor 1 to form a cytokine regulating NK and T cell activities requiring IL-6R for signaling. J Immunol. 2009;183:7692–7702. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wurmbach E, Chen YB, Khitrov G, Zhang W, Roayaie S, Schwartz M, Fiel I, et al. Genome-wide molecular profiles of HCV-induced dysplasia and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2007;45:938–947. doi: 10.1002/hep.21622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Fig. 1 Histological analysis of hematoxylin and eosin staining of paraffin-embedded formalin-fixed tissue of different organs in mice treated with either IL12- or control-encoding plasmid DNA.

Supplemental Fig. 2. Induction of the IL27 subunit IL30 expression via IL12 is mediated through IFNγ and STAT1 binding site ‘a’. (A, B) Induction of IL30 by recombinant IL12 protein (rIL12) (A) and rIFNγ (B) in different cell types (n=3). BMDM, BMDC, SL12.4, and TIB220 represent bone marrow derived macrophages, dendritic cells, naïve T cells, and hybridoma B cells, respectively. (C) Structure of IL30 promoter-luciferase gene constructs and the locations of STAT1 binding sites. (D, E) IL30 promoter activities with and without STAT1 binding site ‘a’ (D) or STAT1 binding site ‘b’(E) in the presence and absence of rIFNγ treatment. Luciferase activity was used to determine the transcriptional activity of the IL30 promoter (n=3). (B, D, E) *, P<0.05, for comparisons between treatments indicated by horizontal lines.

Supplemental Fig. 3. Gene therapy induces robust expression of IL30. Mice were treated with control or IL30-encoding plasmids followed by electroporation, and IL30 expression was determined in the serum via ELISA.

Supplemental Fig. 4. IL30 inhibits the toxicity of the liver independently of IL27 or WSX1. The levels of expression of alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) in the serum of mice treated with a mixture of control and IL12-, IL30- and IL12-, EBI3- and IL12-, or IL27- and IL12-encoding plasmid DNA delivered via electroporation were measured. *, P<0.01, #, P<0.05, comparison of each treatment group to pIL12+pCtr group.

Supplemental Fig. 5. Analysis of IL30 expressed in serum via ELISA of mice treated with a mixture of control and IL12 -encoding plasmid DNA delivered via electroporation either wildtype, EBI3−/−, or WSX1−/− mice. Serum was collected five days after the second treatment.

Supplemental Fig. 6. IL30 inhibits liver necrosis. Histological analysis (A), counts of necrotic areas in a total of fifteen fields (B) of mice treated with 12 μg of a mixture of equal amounts of plasmids as indicated in each panel. *, P<0.05, for comparisons between treatments indicated by horizontal lines.

Supplemental Fig. 7. The livers and spleens of mice treated with a mixture of equal amounts of plasmids as indicated in each panel (n=2) were collected at day 2 after the first treatment (upper panels) or day 5 after the second treatment (lower panels) and analyzed for IFNγ expression via quantitative real-time PCR analysis. Values are expressed as fold changes compared to control treatment. Data represents at least two independent experiments.

Supplemental Fig. 8. IL30 plasmid does not affect CMV-promoter driven expression of IL12 or IFNγ. Cells were co-transfected with the plasmids as indicated in the figure, (B) and IL12 (A), IFNγ (B), and IL30 (C) expression in the supernatant was measured via ELISA (n=3).

Supplemental Fig. 9. Comparison of IL30 expression in the liver of healthy patients or patients with liver cirrhosis, dysplasia, or hepatocellular carcinoma (early and advanced stage) from the data set derived from reference (34).