Introduction

Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of joint replacement surgery for knee and hip osteoarthritis (OA) have long been described [4, 9, 23]. Whether these represent differences in the frequency and severity of OA at various joint sites [11, 12] or differences in patient preference, access to medical care, or other factors has been the source of considerable study in the last 10 to 15 years [6]. This article emphasizes racial/ethnic differences in, and factors associated with, the use or lack of use of various therapeutic interventions for OA, and new insights into potential mechanisms underlying these disparities, with an eye toward understanding how effective modalities might be applied in various populations likely to benefit.

Ethnic Disparity in Care of OA

In 1995, Hoagland and colleagues reported a study of racial/ethnic differences in total hip arthroplasty (THA) in 17 hospitals in the San Francisco area between 1984 and 1988 [9]. Whites were twice as likely as Blacks to have THA, with even lower rates in Hispanic, Filipino, Japanese, and Chinese. While Asians have now been shown to have lower rates than Whites of hip OA that would warrant THA [19], Blacks in the USA have at least equal frequency and severity of hip OA to Whites [11, 24]. Data from the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project (JoCo OA) provided evidence that African Americans (AAs) have specific radiographic features that were associated with hip OA progression and THA in elderly white women in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures, suggesting possible unmet need in AAs [14, 18].

Similarly, despite having at least equal, if not higher, frequency and severity of knee OA [2, 6, 12], AAs are much less likely to undergo total knee arthroplasty (TKA) than Whites [4, 23]. Healthy People 2010, a public health blueprint for the nation, set the elimination of these disparities in the use of TKA for knee OA in adults aged 65 and older as a specified goal [25]. Disappointingly, a recent analysis showed that while the use of this therapeutic intervention had increased 58% overall between 2000 and 2006, AAs continued to be much less likely to undergo this procedure than Whites [4]. Lavernia and colleagues reported that AAs presented pre-operatively for THA and TKA with worse scores than Whites on measures of pain, physical function, and well being; while each group improved post-operatively, AAs continued to have worse scores than Whites up to a mean of 5 years post-operatively [15]. Ibrahim and colleagues observed that AAs in VA Hospitals were less likely than Whites to know about THA and TKA and have different attitudes toward acceptance or consideration of these procedures [10]. More recently, this group reported that orthopedic clinic visits with AA veterans tended to have less discussion of biomedical issues and more rapport-building discussion than with White patients, but no differences were found in the length of visits, overall amount of dialogue, discussion of psychosocial issues, or other means of communication [8]. Another study noted that Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians in California were more likely to have TKA in low volume hospitals [16].

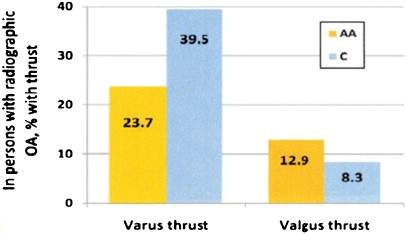

Racial/ethnic differences in pain, function, pain processing, and gait, all of which can affect OA and the propensity to use THA, TKA, and other therapeutics, have also been noted. Allen et al. reported that compared to Whites, AAs in the JoCo OA with knee OA had worse pain and function that was not explained by radiographic severity, but was related to differences in body mass index and depressive symptoms [1]. AAs were also more likely than Whites to have lateral compartment involvement in knee OA, which was not explained by differences in static knee alignment [3, 17]. Consistent with this observation, Chang et al. reported that AAs in the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) were more likely than Whites to have valgus thrust (Fig. 1) [5]. AAs have also been noted to have slower gait speed and lower knee range of motion and loading rate and to take longer to reach peak maximum ground reaction force [21]. In addition to these differences in biomechanics, Singh and colleagues reported differences in allodynia between AA and White men and women in the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study (MOST), most notably higher in AA women; but no differences were found in pinprick or temporal summation [22]. No differences in pain pressure threshold were noted in AA and White men and women in the JoCo OA. Recent genetic variants in the μ-opioid receptor in AAs have been reported, which altered function and changed responsiveness to established μ-opioid receptor ligands [7]. Whether changes such as these are related to racial/ethnic differences in pain and response to medications remains to be tested.

Fig. 1.

African American and Caucasian OA patients with thrust when walking. (Reprinted from Chang et al. [5] copyright 2010, with permission from John Wiley and Sons)

Ethnic Disparity and Future Research

In addition to disparities in the use of THA and TKA, race/ethnicity may influence the use of other relevant therapeutic modalities. AAs are less likely than Whites to be prescribed and to take narcotic prescriptions, sleep medication, and prescription sleep medication and are more likely to use prayer to relieve pain [13, 20]. Whether AAs or other racial/ethnic groups are less willing than Whites to accept intra-articular injections, post-traumatic joint repair, or use of bracing/devices is unknown. Such issues are critical in the design of clinical trials which test such modalities in post-traumatic and idiopathic OA as well as in the dissemination of effective therapies, including THA and TKA in ethnically diverse populations.

Disclosures

I have commercial associations (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article. These include: Johnson & Johnson, Inc.: contract, consultant; Algynomics, Inc.: consultant, stock options; Eli Lilly, Inc.: consultant; and Interleukin Genetics, Inc.: consultant.

References

- 1.Allen KD, Helmick CG, Schwartz TA, DeVellis RF, Renner JB, Jordan JM. Racial differences in self-reported pain and function among individuals with radiographic hip and knee osteoarthritis: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Osteoarthritis & Cartilage. 2009;17(9):1132–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson JJ, Felson DT. Factors associated with osteoarthritis of the knee in the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HANES I): evidence for an association with overweigh, race, and physical demands of work. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128(1):179–189. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braga L, Renner JB, Schwartz TA, Woodard J, Helmick CG, Hochberg MC, Jordan JM. Differences in radiographic features of knee osteoarthritis in African-Americans and Caucasians: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Osteo & Cart. 2009;17(12):1554–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Racial disparities in total knee replacement among Medicare enrollees: United States 2000–2006. [PubMed]

- 5.Chang A, Hochberg M, Song J, Dunlop D, Chmiel JS, Nevitt M, et al. Frequency of varus and valgus thrust and factors associated with thrust presence in persons with or at higher risk of developing knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(5):1403–1411. doi: 10.1002/art.27377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dillon CF, Rasch EK, Gu Q, Hirsch R. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1991–1994. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(11):2271–2279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fortin JP, Ci L, Schroeder J, Goldstein C, Montefusco MC, Reis Se, et al. The opioid receptor variant N190K is unresponsive to peptide agonists yet can be rescued by small-molecule drugs. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:837–845. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.064188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hausmann LRM, Hanusa BH, Kresevic DM, Zickmund S, Ling B, Gordon HS, et al. Orthopedic communication about osteoarthritis treatment: does patient race matter? Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:635–642. doi: 10.1002/acr.20429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoaglund FT, Oishi CS, Gialamas GG. Extreme variation in racial rates of total hip arthroplasty for primary coxarthrosis: a population-based study in San Francisco. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54(2):107–110. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibrahim SA, Siminoff LA, Burant CJ, Kwoh, CK. Differences in expectations of outcome mediate African American/white patient differences in "willingness" to consider joint replacement. Arthritis Rheum 46: 2429–35 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Jordan JM, Helmick CG, Renner JB, Luta G, Dragomir AD, Woodard J, Fang F, Schwartz TA, Nelson AE, Abbate LM, Callahan LF, Kalsbeek WD, Hochberg MC. Prevalence of hip symptoms and radiographic and symptomatic hip osteoarthritis in African Americans and Caucasians: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(4):809–815. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jordan JM, Helmick CG, Renner JB, Luta G, Woodard J, Dragomir AD, Kalsbeek W, Abbate L, Hochberg MC. Prevalence of knee symptoms and radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in African-Americans and Caucasians: The Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(1):172–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim H, Clark D, Dionne RA. Genetic contribution to clinical pain and analgesia. J Pain. 2009;10(7):663–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lane NE, Nevitt MC, Hochberg MC, Hung YY, Palermo L. Progression of radiographic hip osteoarthritis over 8 years in a community sample of elderly white women. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(5):1477–1486. doi: 10.1002/art.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavernia CJ, Alcerro JC, Contreras JS, Rossi MD. Ethnic and racial factors influencing well-being, perceived pain, and physical function after primary total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1838–1845. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1841-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu JH, Zingmond DS, McGory ML, SooHoo NF, Ettner SL, Brook RH et al. Disparities in the utilization of high-volume hospitals for complex surgery. JAMA 2006; 296: 1973–1980. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009 Feb 20;58(6):133–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Nelson AE, Braga L, Braga-Baiak A, Atashili J, Schwartz TA, Renner JB, Helmick CG, Jordan JM. Static knee alignment measurements among Caucasians and African Americans: The Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(9):1987–1990. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson AE, Braga L, Renner JB, Atashili J, Woodard J, Hochberg MC, Helmick CG, Jordan JM. Characterization of individual radiographic features of hip osteoarthritis in African American and White women and men: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Care and Research. 2010;62(2):190–197. doi: 10.1002/acr.20067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nevitt MC, Xu L, Zhang Y, Lui LY, Yu W, Lane NE, Qin M, Hochberg MC, Cummings SR, Felson DT. Very low prevalence of hip osteoarthritis among Chinese elderly in Beijing, China compared with Whites in the United States. Arthritis Rheum 46(7):1773–9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Shavers VL, Bakos A, Sheppard VB. Race, ethnicity and pain among the U.S. adult population. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2010;21(1):177–220. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sims EL, Keefe FJ, Kraus VB, Guilak F, Queen RM, Schmitt D. Racial differences in gait mechanics associated with OA. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2009;21(6):463–469. doi: 10.1007/bf03327442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh JA et al. Racial differences in allodynia. Arthritis Rheum 2010.

- 23.Singh JA. Epidemiology of knee and hip arthroplasty: a systematic review. The Open Orthopaedics Journal. 2011;5:80–95. doi: 10.2174/1874325001105010080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tepper S, Hochberg MC. Factors associated with hip osteoarthritis: data from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137(10):1081–1088. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Healthy people 2010 midcourse review. Washington: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. Arthritis, osteoporosis, and chronic back conditions: objective 2–6. [Google Scholar]