Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Knowledge of number, size and content of insulin secretory granules is pivotal for understanding the physiology of pancreatic beta cells. Here we re-evaluated key structural features of rat beta cells, including insulin granule size, number and distribution as well as cell size.

Methods

Electron micrographs of rat beta cells fixed either chemically or by high-pressure freezing were compared using a high-content analysis approach. These data were used to develop three-dimensional in silico beta cell models, the slicing of which would reproduce the experimental datasets.

Results

As previously reported, chemically fixed insulin secretory granules appeared as hollow spheres with a mean diameter of ∼350 nm. Remarkably, most granules fixed by high-pressure freezing lacked the characteristic halo between the dense core and the limiting membrane and were smaller than their chemically fixed counterparts. Based on our analyses, we conclude that the mean diameter of rat insulin secretory granules is 243 nm, corresponding to a surface area of 0.19 μm2. Rat beta cells have a mean volume of 763 μm3 and contain 5,000–6,000 granules.

Conclusions/interpretation

A major reason for the lower mean granule number/rat beta cell relative to previous accounts is a reduced estimation of the mean beta cell volume. These findings imply that each granule contains about twofold more insulin, while its exocytosis increases membrane capacitance about twofold less than assumed previously. Our integrated approach defines new standards for quantitative image analysis of beta cells and could be applied to other cellular systems.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00125-011-2438-4) contains peer-reviewed but unedited supplementary material, which is available to authorised users.

Keywords: Beta cell, Diabetes, High-content analysis, High-pressure freezing, In silico model, Insulin secretory granule, Transmission electron microscopy

Introduction

The insulin secretory granules (ISGs) are the most characteristic organelles of pancreatic beta cells. In electron micrographs of aldehyde-fixed specimens, ISGs appear as spheres with a diameter of 289–357 nm [1–4]. With stereological techniques, beta cells have been estimated to contain 0.9 × 104 to 1.3 × 104 ISGs [1–4]. Chemical fixation, however, can induce morphological alterations [5, 6], especially due to dehydration [7]. In contrast, cryofixation achieves a more even fixation within milliseconds [8]. High-pressure freezing (HPF) is regarded as the best cryofixation method because of its greater depth of optimal freezing and reliability [8–10].

In this study, the combination of HPF, high-content image analysis (HCA) and in silico modelling allowed us to re-evaluate key features of rat beta cells, including their size and the size and number of their ISGs.

Methods

Islet isolation and cell culture

Pancreatic islets were isolated from four 8-week-old (200–250 g) female Wistar rats as described [11], pooled and then cultured for 24 h in 5.5 mmol/l glucose. Mouse glucagonoma alpha-TC9 cells and rat insulinoma INS-1 cells were cultured as described [12, 13] .

Chemical fixation

Isolated islets, alpha-TC9 and INS-1 cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mol/l cacodylate buffer at room temperature for 2 h and processed for Epon embedding according to standard protocols [13].

High-pressure freezing

Isolated islets, alpha-TC9 and INS-1 cells grown on sapphire discs (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) were incubated with 20% BSA in culture medium for 5 min and then high-pressure frozen using the EMPACT2 + RTS (Leica Microsystems) [14]. Samples were transferred to a freeze substitution device (AFS; Leica Microsystems) for embedding in Epon [14] (electronic supplementary material [ESM] Table 1).

Transmission electron microscopy

Ultrathin (70 nm) sections counterstained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate were viewed with a Tecnai 12 Biotwin Transmission Electron Microscope (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA) with a bottom-mount 2 × 2K F214 CCD camera (TVIPS, Gauting, Germany). Micrographs of beta and alpha-TC9 cells were taken at 6,800 and 11,000 magnifications, respectively. Composite images of one or more complete cells were collected with automated acquisition and stitching software (EM menu 3, TVIPS).

High-content image analysis

Beta cells were recognised as light cells having a nucleus and at least one granule with an electron-dense core surrounded by halo and membrane. Their plasma membranes and nuclear borders were manually marked in transmission electron microscopy (TEM) micrographs. Scanned images were elaborated with ImageJ (National Insitutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) to generate a mask of the cell and the nucleus, and imported into Developer XD (Definiens, Munich, Germany) [15]. With a script developed in Developer XD, ISGs were automatically identified as objects inside the cell mask with an electron-dense core (variables listed in ESM Methods 1). Hierarchical connection allowed the distinction of two classes of core-containing objects: cores with (ISGs[Halo+]) or without (ISGs[Halo−]) a surrounding halo and membrane. The software also calculated the proximity of core-containing objects to the plasma membrane, thus identifying one class of cores and one of granules whose distance from the plasma membrane was smaller than their major radius.

Slicing of in silico three-dimensional beta cells

Based on the data from HPF or chemically fixed specimens, we generated two in silico beta cell models. The HPF beta cell model was a prolate ellipsoid with axes a = b = 8.1 μm < c = 22.1 μm and a spherical nucleus with diameter D n = 5.6 μm. The nucleus was displaced from the cell centre by (c/4) along the long axis of the ellipsoid, as observed in real beta cells. Each in silico beta cell was then cut such that its nucleus was visible in the resulting quasi-two-dimensional (2D) slice, where its apparent diameter was restricted to be larger than D n/2. Sectioning of the beta cell in random directions generated a diversity of slices with thickness of 70 nm like experimental slices.

Definition of granule true size distribution

As ISGs are larger than 70 nm, they are cut at different positions. Even if all ISGs were identical in size, their apparent size difference would result in an observed size distribution (OSD). The true size distribution (TSD) was reconstructed from the OSD using an algorithm inspired by Weibel [16], which assumed spherical ISGs. For a sphere of any size, the apparent size distribution upon slicing (refSD) is known, which allows reconstruction of the TSD from the empirical OSD (ESM Methods 2).

Statistical analysis

The OSDs were compared using the non-parametric two-samples Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, where the p value and statistics (D) were provided (ESM Methods 3). Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

Results

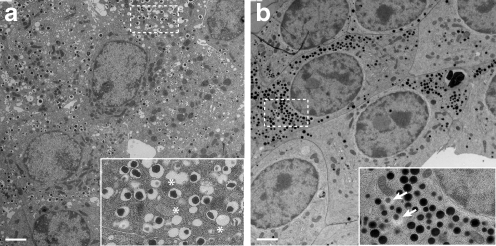

HPF-fixed insulin granules lack a prominent halo

Beta cells account for 65–75% of the rat islet cells [17]. By electron microscopy, they appear lighter than alpha cells [18] (ESM Fig. 1a) and their ISGs have a unique morphology (Fig. 1a). Upon aldehyde fixation, these appear spherical with an electron-dense core separated from the confining membrane by an electron-transparent halo (Fig. 1a, inset). Granules of the other islet endocrine cells lack a similar halo. Strikingly, beta cells fixed by HPF and embedded in Epon appeared different. Their plasma membrane and all intracellular compartments were sharper, while the grey intensity of their cytoplasm was more homogeneous than in chemically fixed samples, especially because of the lack of electron-transparent areas (Fig. 1b and ESM Fig. 1a). Most ISGs lacked a halo or this was of intermediate electron density, suggesting a proteinaceous content (Fig. 1b, inset). The occurrence of some ISGs with a prominent halo nevertheless enabled the unequivocal recognition of beta cells (Fig. 1b, ESM Fig. 1a). As in primary beta cells, ISGs of HPF, Epon-embedded INS-1 cells were more electron dense than those of chemically fixed INS-1 cells and lacked the typical halo (ESM Fig. 2). Insulin immunolabelling of HPF-fixed INS-1 cells indicated that this was only positive upon embedding in Lowicryl (ESM Fig. 3). However, the ultrastructural integrity of these cells was unsatisfactory compared with Epon-embedded HPF INS-1 cells (ESM Fig. 2b). Hence, all subsequent analyses were performed in Epon-embedded islets after fixation with aldehydes or HPF.

Fig. 1.

Appearance of ISGs in chemically and HPF fixed beta cells. Representative electron micrographs of beta cells in isolated pancreatic islets fixed either chemically (a) or with HPF (b); scale bars on the bottom left: 4 μm. The insets show a higher magnification (×3 the original) of the areas marked with a dashed rectangle. In (a), asterisks identify ‘ghost’ ISGs. In (b), arrows point to ISGs with halos

The automated recognition of insulin granules is reliable

Electron micrographs of beta cells fixed either chemically (69) or by HPF (64) from two independent sets were selected for semi-automated HCA. Using algorithms in Developer XD, we developed a protocol for the computer-assisted segmentation of beta cell images and the identification of ISGs (Fig. 2a–d). We quantified 24 variables in each cell, including number, size and electron density of the ISGs as well as their position relative to the plasma membrane and the nucleus (ESM Methods 1). The essential variable for automated recognition of ISGs was the presence of an electron-dense core. With this procedure, ISGs were classified as cores lacking (ISG[Halo−], Fig. 2e) or possessing (ISG[Halo+], Fig. 2f–g) a surrounding halo and a membrane. ISG[Halo+] were further divided into those with a continuous membrane profile (Fig. 2f) or only a partial membrane profile (Fig. 2g). In many cases, the software could ‘fill’ such membrane discontinuities. Notably, only 2% of HPF-fixed ISGs showed a membrane discontinuity that could not be automatically ‘closed’, compared with 22% of chemically fixed ISGs. This suggests that rupture of the ISG membrane was much less common upon HPF than chemical fixation. In the following analysis, however, ISG[Halo+] were considered as a single category because the lack of a continuous membrane profile is an artefact.

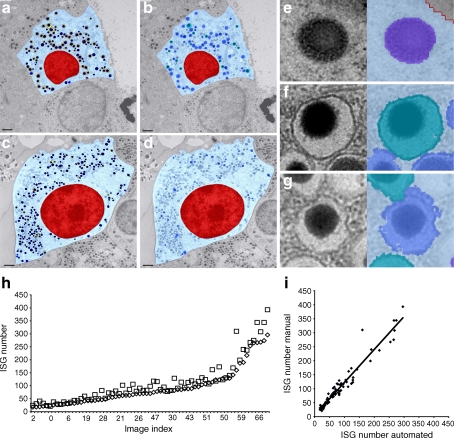

Fig. 2.

Automated recognition of ISGs for HCA. Representative images illustrating the object detection with automated HCA. a,c Detection of insulin cores and the surrounding halo in chemical and HPF fixed beta cells, respectively. Colour code: red, nucleus; light blue, cytoplasm; dark blue, insulin cores; yellow, halo; blue, ISG proximal to the plasma membrane, i.e. with the centre of the core being closer to the plasma membrane than the mean ISG radius. Scale bars: 2 μm. b,d Detection of ISGs with halo in chemical and HPF fixed beta cells, respectively. Colour code: red, nucleus; light blue, cytoplasm; dark blue, ISG with halo but non-closed membrane; light green, ISG with halo and closed membrane. Scale bars 2 μm. e–g Examples of insulin cores (e), ISG with halo and closed membrane (f) and ISG with halo but non-closed membrane (g). h Comparison of manual vs automated scoring of 69 TEM micrographs. The squares and diamonds represent the number of ISGs counted either manually or automatically, respectively. i Pearson’s correlation test between the manual and the automated scoring of ISGs. The high correlation (r = 0.96) indicates the consistency of the automated scoring with the manual counting

We verified the reliability of our approach by comparing the numbers of ISGs automatically recognised by the software and by conventional visual inspection. This analysis, which was performed in a blind manner by a member of our team (JD) who had not been involved in developing the protocol for HCA, was carried out on the first set of images including 35 HPF-fixed and 34 chemically fixed beta cells (Fig. 2h). HCA systematically underestimated the manual counting in HPF and chemically fixed samples by 17.4 ± 13.1% and 17.2 ± 17.4%, respectively. Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the two measurements was 0.96 (Fig. 2i), indicating the reliability of the automated counting method. The systematic underscoring of this protocol resulted from the high stringency of the rule set for the automated ISG recognition and classification.

Detection of more granules in HPF-fixed beta cells than in chemically fixed beta cells

We analysed two independent sets of beta cell images for each fixation method. The results of the two experimental sets are shown in ESM Table 2 and ESM Figs 4 and 5. The number of ISGs counted in 64 HPF-fixed beta cells was 6,577 compared with 6,013 in 69 chemically fixed beta cells (Table 1). The detection of fewer ISGs in the latter may correlate with the presence of numerous vacuoles (Fig. 1a, asterisks), which were absent from HPF-fixed beta cells. Given their abundance and morphology, these vacuoles are conceivably ISG ‘ghosts’ that had lost their dense core during the specimen processing. The ISG[Halo+] were fewer in HPF-fixed (1,186 granules; 18.0%) than in chemically fixed (3,858 granules, 64.2%) beta cells.

Table 1.

ISG counting in TEM images of beta cells fixed by the HPF or chemical method

| Fixation | n | Total ISG | ISG[Halo−] | % ISG[Halo−] | ISG[Halo+] | % ISG[Halo+] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPF | 64 | 6577 | 5391 | 82.0 | 1186 | 18.0 |

| Chemical | 69 | 6013 | 2155 | 35.8 | 3858 | 65.2 |

The number of evaluated slices, the total number of ISGs with (ISG[Halo+]) and without (ISG[Halo−]) halo, and their respective percentages are provided separately for the HPF and chemical fixation methods. These values correspond to the sum of two independent section series, the respective results of which are shown in ESM Table 2

Insulin granules are smaller in HPF-fixed than in chemically fixed beta cells

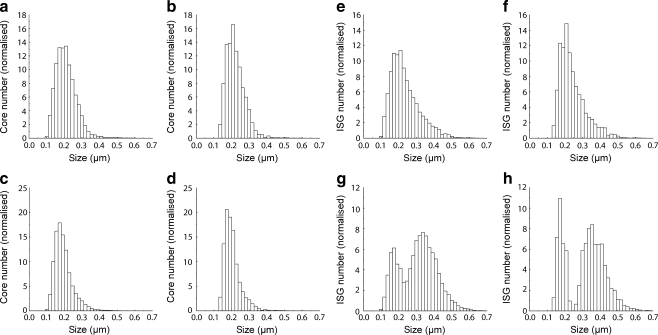

To investigate the cause of these discrepancies, we measured the observed mean diameter (OMD) and OSD of the dense cores and the ISG limiting membrane in both specimen types. As the true mean diameter (TMD) of ISGs is larger than the slice thickness of 70 nm, the ISG section will appear smaller than or equal to its real three-dimensional (3D) size. The number of observed ISGs was statistically sufficient to reconstruct their TMD and TSD from the OMD and OSD using an iterative algorithm (ESM 2). The dense core OMDs in HPF and chemically fixed ISGs were 210 ± 57 and 195 ± 52 nm (D = 0.1516, p < 2.0 × 10−32), respectively, corresponding to TMDs of 222 ± 51 and 204 ± 47 nm, respectively (Fig. 3a–d). The ratio of the core major and minor axes in HPF and chemically fixed ISGs was 1.13 and 1.11, respectively, indicating the nearly spherical geometry of ISGs. The OMDs of HPF and chemically fixed ISGs were 235 ± 80 and 307 ± 103 nm (D = 0.3833, p < 2.0 × 10−32), respectively. The corresponding TMDs were 243 ± 73 and 313 ± 108 nm, respectively (Fig. 3e–h). The large difference between the TMDs of HPF and chemically fixed ISGs resulted from the dominant contribution of ISG[Halo+] in chemically fixed specimens. Conversely, the OMDs of HPF and chemically fixed ISG[Halo+] were very close, being 347 ± 68 and 364 ± 71 nm (D = 0.0980, p = 4.692 × 10−8), respectively, corresponding to TMDs of 378 ± 58 and 394 ± 63 nm.

Fig. 3.

Observed and true size distributions of electron-dense cores and ISGs. a–d OSD (a,c) and TSD (b,d) of electron-dense cores for HPF (a,b) and chemical (c,d) fixation. e–h OSD (e,g) and TSD (f,h) of ISGs for HPF (e,f) and chemical (g,h) fixation. The y axes show the percentage of the cores and the granules in each bin. Hence, the total area under each curve equals 100%

The OSD and TSD of chemically fixed ISGs were bimodal, reflecting the abundance of both ISG[Halo−] and ISG[Halo+] and their significant size difference (Fig. 3g,h). The OSD and TSD of HPF-fixed ISGs were instead monomodal, albeit skewed to the right by the minor fraction of ISG[Halo+] (Fig. 3e,f, ESM Fig. 4c,d). Notably, the OSDs and TSDs of the cores were monomodal, regardless of the fixation type (Fig. 3a–d, ESM Figs 4a, b, 5a, b).

To test whether the different appearance and size distribution of chemically and HPF fixed ISGs resulted from a generalised shrinkage upon HPF fixation, we compared nuclear and cell sizes. The cell major (12.54 ± 3.29 vs 12.50 ± 2.80 μm, D = 0.1386, p = 0.5154) and minor (7.74 ± 2.0 vs 8.49 ± 1.47 μm, D = 0.3306, p = 0.000988) axes as well as the nuclear major (5.35 ± 1.51 vs 5.36 ± 1.31 μm, D = 0.0865, p = 0.9568) and minor (4.22 ± 1.18 vs 4.52 ± 1.18 μm, D = 0.1816, p = 0.2009) axes of HPF and chemically fixed beta cells did not significantly differ except for <10% in the cell minor axis. If the smaller size of HPF-fixed ISGs was due to general shrinkage, HPF-fixed cells should have been comparably smaller. Hence the alternative explanation is that chemical fixation causes swelling of ISGs.

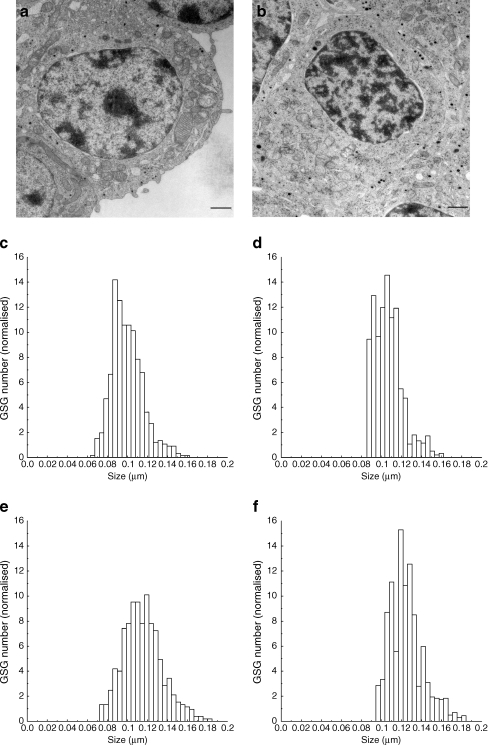

Chemical fixation enlarges granules irrespective of their cargo

To test whether chemical fixation enlarges granules irrespective of their cargo, we analysed glucagon secretory granules (GSGs) in alpha-TC9 cells, a prototypic model of peptide-secreting endocrine cells other than beta cells. The choice of a cell line rather than primary cells precluded any doubt about the identity of the cells and their cargo. Alpha-TC9 cells were fixed chemically or by HPF. As expected, GSGs did not display a prominent halo (Fig. 4a,b) and the OSDs and TSDs were monomodal (Fig. 4c–f) irrespective of the fixation method. However, chemically fixed GSGs were significantly larger than HPF-fixed GSGs (125 ± 17 vs 107 ± 14 nm, D = 0.3501, p = 2.762 × 10−32; ESM Table 3). These findings support the suggestion that chemical fixation prompts the swelling of granules regardless of their peptide content.

Fig. 4.

Appearance and size distributions of GSGs in chemically and HPF fixed glucagonoma cells. Representative electron micrographs of mouse alpha-TC9 glucagonoma cells fixed either chemically (a) or with HPF (b) (scale bars: 900 nm). OSD (c,e) and TSD (d,f) of electron-dense cores for HPF (c,d) and chemical (e,f) fixation. The y axes show the percentage of the cores in each bin. Hence the total area under each curve equals 100%

Development of 3D in silico beta cell models consistent with 2D experimental data

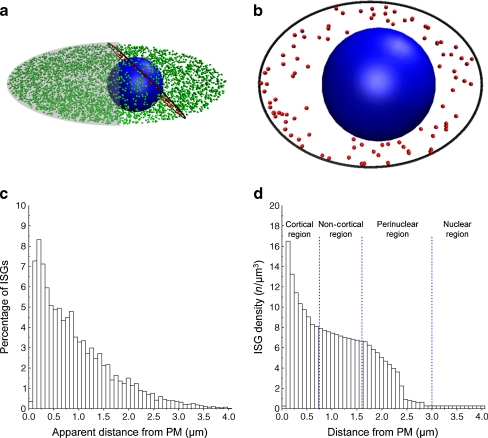

Rat beta cells have been estimated to have a mean diameter of 13.2 μm [4] (ESM Table 4). This value is close to the cell major axis measured here (Table 2, 2D Cell L maj). However, beta cells are clearly anisotropic, with their minor axis being considerably shorter than their major axis (Table 2). The information about the ISGs depends on where the beta cell was cut. Hence, the assumption of a spherical geometry for estimating 3D quantities from quasi-2D TEM images, including mean beta cell size, number of ISGs/cell and distribution of ISGs, can be misleading. Based on the data collected by HCA, we developed an in silico 3D model of a beta cell fixed by HPF or chemically (Table 2). Both models were sectioned as the experimental specimens to verify whether the in silico slices reproduced the experimental quasi-2D images (Fig. 5a,b). In the following, we report the values derived from the HPF-based in silico 3D model of an average beta cell unless specified otherwise.

Table 2.

Comparison of experimental and in silico variables of HPF-fixed and chemically fixed beta cells

| Type of results | 2D Cell L maj (μm) | 2D Cell L min (μm) | 2D Nuc L maj (μm) | 2D Nuc L min (μm) | 3D Cell L maj (μm) | 3D Cell L min (μm) | 3D Nuc diameter (μm) | Cell surface (μm2) | Cell volume (μm3) | Apparent A frac (%) | ISG V frac (%) | Apparent density (μm−3) | True density (μm−3) | Total ISG number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPF exp | 12.54 ± 3.29 | 7.74 ± 2.00 | 5.35 ± 1.51 | 4.22 ± 1.18 | – | – | – | – | – | 9.9 ± 5.2 | – | 32.10 ± 14.80 | – | – |

| HPF model | 12.49 ± 4.41 | 7.69 ± 0.42 | 4.77 ± 0.73 | 4.77 ± 0.73 | 22.1 | 8.12 | 5.59 | 465.5 | 762.7 | 9.9 ± 1.5 | 7.2 | 30.26 ± 3.85 | 7.8 ± 1.7 | 4950 |

| CHEM exp | 12.50 ± 2.80 | 8.49 ± 1.47 | 5.36 ± 1.31 | 4.52 ± 1.18 | – | – | – | – | – | 11.7 ± 5.3 | – | 23.56 ± 11.19 | – | – |

| CHEM model | 12.55 ± 3.39 | 8.54 ± 0.39 | 4.92 ± 0.75 | 4.92 ± 0.75 | 19.4 | 8.90 | 5.76 | 458.0 | 803.9 | 11.7 ± 1.5 | 9.5 | 21.69 ± 2.61 | 4.4 ± 1.1 | 3050 |

The measured dataset for HPF (first 2 rows) and chemical (last 2 rows) fixation were used to reconstruct two corresponding 3D in silico beta cell models. The experimental slicing procedure was then repeated in silico and the following experimental (first and third row) and in silico (second and fourth row) results are shown: the major (2D Cell L maj, 2D Nuc L maj) and minor (2D Cell L min, 2D Nuc L min) axes of the cell and the nucleus in slices of 70 nm thickness; the major (3D Cell L maj) and minor (3D Cell L min) axes of the reconstructed beta cell models; the corresponding diameter of the 3D nucleus (3D Nuc diameter), cell surface and the cell volume; the apparent fraction of the surface in the slices occupied by ISG (A frac) and the apparent density of ISGs in experiment and model; the corresponding fraction of cell volume in the 3D beta cell model occupied by ISGs (ISG V frac) and the reconstructed true density in the beta cell model; the total ISG number per beta cell consistent with the experimental data

Fig. 5.

In silico slicing of the HPF beta cell model and ISG distribution. a Schematic view of 3D in silico beta cell model. The nucleus is blue, and ISGs are green. ISGs intersected by the slice depicted in black are red. b In silico slice. c Apparent distance of ISGs from the plasma membrane (PM) in in silico slices. d ISG density in the 3D beta cell model. Changes in the ISG density were associated with different cell compartments as indicated with dotted blue lines

To generate an in silico beta cell, we first defined its shape and size. As beta cells were elongated in 2D images, the HPF-fixed beta cell was modelled as a prolate ellipsoid with axes a = b = 8.12 μm < c = 22.1 μm, and a spherical nucleus with diameter of 5.59 μm (Table 2). The cell dimensions were chosen such that in silico slicing led to axis and diameter distributions matching those observed experimentally (ESM Fig. 6). The success of this fitting justified a posteriori the choice of an ellipsoidal shape and was not achieved starting from a spherical cell. The surface area and volume of the HPF beta cell model were 466 μm2 and 763 μm3, respectively, with a nucleus of 91 μm3.

Next, ISGs were incorporated into the in silico HPF beta cell. Because of their almost circular appearance in electron micrographs, ISGs were approximated as spheres of different sizes using the TSD defined above (Fig. 3f). The spatial distribution of ISGs was reconstructed through an iterative fitting procedure, as their apparent distance from the plasma membrane in 2D micrographs differs from their true distance in 3D. After slicing of the in silico beta cell (Fig. 5b), the ISG distribution of distances from the plasma membrane (Fig. 5c) was fitted to the experimental 2D distribution (ESM Fig. 7). ISGs were then inserted into the in silico beta cell according to the reconstructed spatial distribution (Fig. 5d). Hence, slicing of the in silico beta cell generated (1) the distribution of major and minor cell axes (Table 2, ESM Fig. 6), (2) the OSD (ESM Fig. 7) and (3) the distribution of ISG distances from the plasma membrane (ESM Fig. 8), all of which matched the experimental results.

The experimental data are statistically sufficient for in silico beta cell analysis

To determine the number of experimental slices needed for statistical reliability, we generated in silico between 10 and 50,000 slices (ESM Fig. 9). As all analysed quantities varied <6% when >60 slices were used, the number of slices collected from HPF (64) and chemically (69) fixed beta cells was considered to be sufficient.

Rat beta cells contain fewer insulin granules than assumed

The number of ISGs/beta cell was deduced by fitting the in silico cytosolic area fraction (cell area without nucleus) that ISGs occupied to the corresponding experimental value (apparent A frac in Table 2). ISGs occupied on average 9.9% and 7.2% of the cytosolic area and volume of HPF-fixed beta cells, respectively (Table 2). Our model was reliable, as the apparent density of ISGs in 70 nm slices of the in silico beta cell was in agreement with the experimental value within one standard deviation (Table 2). The mean number of ISGs in the HPF-fixed beta cell was 4,950, while in the chemically fixed beta cell it was 3,050. Taking into account the 17% underestimation of ISG count by HCA, the HPF and chemically fixed beta cells contain on average ∼5,800 and ∼3,600 ISGs, respectively. Independent tests verified that the systematic error of the automated granule counting on 2D sections did not preclude the correct extrapolation of granule number in 3D (ESM Methods 4). This estimate was not significantly influenced by the size variability of the nucleus in different slices (ESM Methods 5).

Discussion

The rationale of our strategy, its limits and transferability

Our results originated from the integrated application of three state-of-the-art methodologies, namely HPF electron microscopy, semi-automated HCA of digital TEM images and in silico cell modelling. The outcome is a quantitative view of rat ISGs and beta cells that diverges substantially from previous accounts (ESM Table 3). The transferability of our findings to ISGs and beta cells in other species remains to be established.

Cryofixation, especially HPF, preserves all cellular compartments better than chemical fixation [8]. In beta cells, the typical ISG ‘ghosts’ lacking a dense core were absent, the number of ISG[Halo+] was greatly reduced, and organelles and the entire cytoplasm were more compact and defined than their chemically fixed counterparts. The semi-automated HCA of 2D electron microscopy images provided additional advantages over conventional morphometry. Not only were ISGs reliably recognised, their coordinates could be measured relative to all other ISGs, the plasma membrane and the nucleus. In addition, the apparent size of the cell and nucleus major and minor axes were precisely assessed. This information was instrumental for elaborating an in silico model of an ‘average’ rat beta cell. Thus we could overcome the major obstacle of morphometry, i.e. the extrapolation of 3D information from images of quasi-2D slices. To accurately determine the mean number of ISGs per beta cell, we generated a 3D beta cell model with properties that reproduced the experimental dataset upon in silico slicing. The modelling of the cell as a prolate ellipsoid, but not as a sphere, was sufficient to consistently reproduce all experimental data. Notably, our methodology is applicable to virtually any cell type, the content of which is deduced from 2D images.

The case of the halo: granule swelling versus shrinkage

HPF-fixed beta cells contained mostly ISG[Halo−] and fewer ISG[Halo+] than chemically fixed cells. As ISG[Halo+] are the hallmark of beta cells, these findings were remarkable, yet very robust, being derived from a large number of sections. Moreover, the OMDs of 347 ± 68 and 364 ± 71 nm for ISG[Halo+] in HPF and chemically fixed cells were consistent with previous studies using chemical fixation [1–4], which reported ISG OMDs in the range 289–357 nm (ESM Table 4).

One explanation for the strikingly different percentage of ISG[Halo−] between the two fixation types (Table 1) may be the extraction of cytosolic material, and hence the shrinkage of cellular structures upon chemical fixation [19]. If all cellular structures shrink, while the rigid insulin crystal (see next paragraph) remains intact, ISG membranes could be torn apart from the cores. Alternatively, destruction of the chemiosmotic gradient between the vesicle lumen and the cytoplasm by chemical fixation, followed by the sudden entry of water, could cause abrupt swelling of granules, rupture of their membranes, and the erosion and even complete loss (ISG ‘ghosts’) of their dense core.

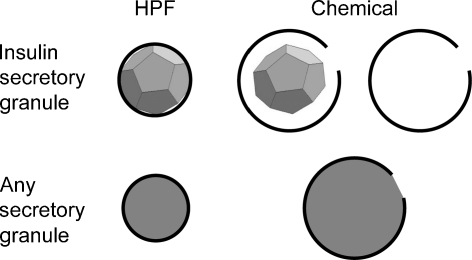

As all secretory granules have a chemiosmotic gradient across their membranes, why is a prominent halo a unique feature of ISGs? The likely explanation is that insulin, the major ISG cargo, is the only neuropeptide hormone that crystallises. Therefore the ISG matrix may be more refractory to expanding concomitantly with the surrounding membrane than the matrix of other granules. Notably, guinea pig ISGs, the insulin of which does not crystallise [20], display only a thin halo [21]. Similar observations were made in mice lacking prohormone convertase 1/3, which is mainly responsible for converting proinsulin into insulin [22]. Unlike insulin, proinsulin may not crystallise [23]. Accordingly, ISGs with limited halo have been regarded as immature [24]. Hence, our data strongly suggest that chemical fixation induces expansion of granules and that the halo is an artefact, the magnitude of which reflects the different composition and solubility of cargoes in different endocrine cells (Fig. 6). The presence of ISG[Halo+] in HPF beta cells indicates that even HPF cannot completely prevent this artefact.

Fig. 6.

Cartoon of the different size and appearance of granules upon HPF and chemical fixation. Owing to its crystal core, the matrix of the chemically fixed insulin granules does not expand concomitantly with its enclosing membrane. This dissociation is responsible for the generation of the characteristic halo and, in many instances, for the complete loss of the cargo during the processing of the samples. In all other secretory granules, the core swells concomitantly with the surrounding membrane, explaining the lack of a halo. Swelling is postulated to rupture the granule membrane, which is due to the limited elasticity of the lipid bilayer

The mean ISG diameter of 243 nm implies a mean surface and volume of 0.19 μm2 and 7.5 × 106 nm3, respectively, i.e. only 50% and 34% of the corresponding values (0.38 μm2 and 22 × 106 nm3) for an ISG with a diameter of 348 nm [4] (ESM Table 4). Accordingly, about twofold more granules should undergo exocytosis to account for the same increase in surface area as estimated through capacitance measurements. High-resolution capacitance indicated that the mean diameter of human ISGs is 305 ± 3 nm [25]. However, this value was increased by several outlier events, while the geometric mean was ∼250 nm, which is close to the diameter calculated here for rat ISGs. Furthermore, our results are consistent with the mean ISG diameter (245 and 280 nm) reported from two HPF-fixed beta cells analysed by electron tomography [26].

Beta cells are smaller than assumed

The mean surface area of the in silico beta cell was 466 μm2. This value is at the lower limit of the surface area between ∼450 and ∼900 μm2 estimated through capacitance measurements assuming a capacitance of 10 fF/μm2 [27–30]. Such measurements, however, were obtained from single dispersed beta cells or cells at the islet margin, whereas our data originate from beta cells in situ located throughout the islet. The volumes of the in silico HPF and chemically fixed beta cell models are 763 and 804 μm3, respectively. These estimates are in good agreement with the volumes of 610 and 698 μm3 reported for the two beta cells reconstructed by 3D tomography [26]. Thus a self-consistent analysis leads to the conclusion that the mean volume of rat beta cells is remarkably smaller than the previously estimated volumes of 1,202–1,434 μm3, depending on the species [1–4] (ESM Table 4). These overestimations resulted from the modelling of beta cells as spheres with diameters equal to their observed major axis (ESM 6).

The mean number of ISGs/beta cell fixed with HPF was 5,000–6,000, which is ∼50% of the previously assumed number and close to the mean value (6,420) of the two beta cells reconstructed by 3D tomography [26]. The smaller number of ISGs/beta cell is mainly the consequence of the smaller cell size (ESM 6). Exclusion of the nucleus from the cell volume further reduced this number. Finally, since the true density of ISGs is substantially smaller than the apparent density (Table 2), the density of ISGs derived with the stereological approach was overestimated.

Implications of our findings for beta cells and beyond

Based on the assumption that each beta cell contains ∼13,000 ISGs, it was concluded that each granule carries ∼2 × 105 insulin molecules [31]. Following ISG purification on iso-osmotic gradients [32] or amperometric measurements [33], it was instead estimated that each rat ISG contains at most (8–9.6) × 105 molecules. These values, however, were extrapolated assuming that rat ISGs have a mean diameter of 342 nm, i.e. a volume of 21 × 106 nm3. Since a beta cell contains only 5,000–6,000 ISGs, each with a volume of 7.5 × 106 nm3, these previous discordant findings can be reconciled, estimating each ISG to contain ∼(3–4) × 105 insulin molecules. This conclusion is relevant for accurate quantification of how different stimuli affect insulin production and turnover.

On a methodological level, we have combined three state-of-the-art techniques to achieve the highest degree of reliability. The greater accuracy of data collected from HPF-fixed specimens became fully apparent after the HCA and further elaboration of these data with a 3D agent-based mathematical model of the beta cell and its organelle content. The iterative repetition of identical experimental protocol in silico allowed a consistent 3D interpretation of the quasi-2D empirical data. Given the improvement in the data analysis obtained with this approach, its wide application could be valuable for future quantitative imaging studies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Electron micrograph of an isolated pancreatic islet fixed by HPF. (a) The asterisk indicates a darker cell, conceivably an alpha cell, surrounded by lighter beta cells. Scale bar: 1 μm. (b) High magnification (2.2×) of (a) showing a granule near the Golgi complex with a halo (arrow 1) and a second with a protrusion resembling a small budding vesicle (arrow 2). To appreciate these details zooming into the on-line digital file is recommended. (c) High magnification (3.5×) of (a) showing several vesicles of various sizes near the plasma membrane and with a light electron dense matrix. These vesicles conceivably represent endosomes at different stages of reciprocal fusion and fission (PDF 5,562 kb)

Appearance of ISGs in chemically and HPF fixed INS-1 cells. Representative electron micrographs of INS-1 cells fixed either chemically (a) or with HPF (b) and embedded in Epon. The insets show a higher magnification of the areas marked with a dashed rectangle. (a) Scale bar in overview: 2 μm, in the inset: 100 nm. (b) Scale bar: 2 μm, magnification of the inset 3.1× of the original. (PDF 11,600 kb)

Electron micrograph of INS-1 cells fixed by HPF, embedded in Lowicryl HM20 and labelled for insulin. The inset shows a higher magnification (1.7×) of the area marked with a dashed rectangle. Scale bar on the bottom left corner: 100 nm (PDF 6,640 kb)

TSD of electron dense cores and ISGs fixed with HPF. (a–d) show the TSD of electron dense cores (a, b) and ISGs (c, d) in the first (a, c) and second (b, d) set of experimental sections. In both experiments based on HPF the size distributions of cores and ISGs are monomodal, in contrast to experiments based on chemical fixation (Fig. S5; PDF 89 kb)

TSD of chemically fixed electron dense cores and ISGs. (a–d) show the TSD of electron dense cores (a, b) and ISGs (c, d) in the first (a, c) and second (b, d) set of experimental sections. In both experiments based on chemical fixation the size distribution of cores is monomodal, while it is bimodal for ISGs in contrast to HPF fixation (Fig. S4; PDF 84 kb)

Distribution of major and minor axis. The experimentally measured distribution of the major (a) and minor (b) axes are shown for HPF fixed beta cells. The corresponding distributions from in silico slicing are shown in (c) and (d). Note that this distribution was generated starting from cells with variable size (PDF 82 kb)

The OSD of ISGs in HPF and chemically fixed beta cells. The OSD of ISGs resulting from experiments is shown in (a) for HPF and in (c) for chemically fixed beta cells. The corresponding differences of the experimental and in silico generated distributions are shown in (b) and (d); PDF 83 kb

Distribution of ISGs in beta cells. The apparent distance of ISGs from the PM in experiments is shown in (a) for HPF and in (c) for chemically fixed beta cells. The corresponding differences of the experimental and in silico generated distributions are shown in (b) and (d); PDF 67 kb

Dependency of various parameters on the number of slices. Values were normalised to those generated with 50,000 slices (PDF 73 kb)

PDF 52.4 kb

PDF 54.5 kb

PDF 52.6 kb

PDF 59.6 kb

PDF 110 kb

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Efrat (Tel Aviv University, Israel) for the gift of mouse glucagonoma alpha-TC9 cells, P. MacDonald (University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada), J.-C. Henquin (University of Bruessels, Belgium), C. Wollheim (University of Geneve, Switzerland), P. Halban (University of Geneve, Switzerland) and S. Solimena for discussion, P. de Camilli (Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA) for critical comments, A. Lohmann (Dresden University of Technology, Germany) and C. Wegbrod (Dresden University of Technology, Germany) for technical assistance, and T. Kurth (Dresden Unviversity of Technology, Germany) for advice.

Funding

This work has been supported in part by funds to M. Solimena from the Max Planck Society and from the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) to the German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD e.V.), and to M. Meyer-Hermann from the BMBF projects GerontoMitoSys and GerontoShield, as well as from the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies (FIAS).

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

MS and MM-H developed the concept and design of the research, analysed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. EF, JD, JO, AM, AN and PV generated, analysed and interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the version to be published.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- 2D

Two-dimensional

- 3D

Three-dimensional

- GSG

Glucagon secretory granule

- HCA

High-content image analysis

- HPF

High-pressure freezing

- ISG

Insulin secretory granule

- OMD

Observed mean diameter

- OSD

Observed size distribution

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

- TMD

True mean diameter

- TSD

True size distribution

Footnotes

E. Fava and J. Dehghany contributed equally to this study.

Contributor Information

M. Meyer-Hermann, Email: michael.meyer-hermann@helmholtz-hzi.de

M. Solimena, Email: michele.solimena@tu-dresden.de

References

- 1.Dean PM. Ultrastructural morphometry of the pancreatic beta cell. Diabetologia. 1973;9:115–119. doi: 10.1007/BF01230690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sato T, Herman L. Stereological analysis of normal rabbit pancreatic islets. Am J Anat. 1981;161:71–84. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001610106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olofsson CS, Göpel SO, Barg S, et al. Fast insulin secretion reflects exocytosis of docked granules in mouse pancreatic B cells. Pflugers Arch. 2002;444:43–51. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0781-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Straub SG, Shanmugam G, Sharp GWG. Stimulation of insulin release by glucose is associated with an increase in the number of docked granules in the beta cells of rat pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 2004;53:3179–3183. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crang RFI, Klomparens KL. Artifacts in biological electron microscopy. New York: Plenum Press; 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kellenberger E, Johansen R, Maeder M, Bohrmann B, Stauffer E, Villiger W. Artefacts and morphological changes during chemical fixation. J Microsc. 1992;168:181–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1992.tb03260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Small JV. Organization of actin in the leading edge of cultured cells: influence of osmium tetroxide and dehydration on the ultrastructure of actin meshworks. J Cell Biol. 1989;91:695–705. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.3.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahl R, Staehelin LA. High-pressure freezing for the preservation of biological structure: theory and practice. J Electron Microsc Tech. 1989;13:165–174. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1060130305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald K. High-pressure freezing for preservation of high resolution fine structure and antigenicity for immunolabeling. Methods Mol Biol. 1999;117:77–97. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-678-9:77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonald KL, Morphew M, Verkade P, Müller-Reichert T. Recent advances in high-pressure freezing: equipment- and specimen-loading methods. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;369:143–173. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-294-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gotoh M, Maki T, Kiyoizumi T, Satomi S, Monaco AP. An improved method for isolation of mouse pancreatic islets. Transplantation. 1985;40:437–438. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198510000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powers AC, Efrat S, Mojsov S, Spector D, Habener JF, Hanahan D. Proglucagon processing similar to normal islets in pancreatic alpha-like cell line derived from transgenic mouse tumor. Diabetes. 1990;39:406–414. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.39.4.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knoch K, Bergert H, Borgonovo B, et al. Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein promotes insulin secretory granule biogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:207–214. doi: 10.1038/ncb1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verkade P. Moving EM: the Rapid Transfer System as a new tool for correlative light and electron microscopy and high throughput for high-pressure freezing. J Microsc. 2008;230:317–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2008.01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baatz M, Arini N, Schäpe A, Binnig G, Linssen B. Object-oriented image analysis for high content screening: detailed quantification of cells and sub cellular structures with the Cellenger software. Cytometry A. 2006;69:652–658. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weibel ER. Stereological methods. London, New York: Academic Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baetens D, Malaisse-Lagae F, Perrelet A, Orci L. Endocrine pancreas: three-dimensional reconstruction shows two types of islets of langerhans. Science. 1979;206:1323–1325. doi: 10.1126/science.390711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caramia F. Electron microscopic description of a third cell type in the islets of the rat pancreas. Am J Anat. 1963;112:53–64. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001120104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murk JLAN, Posthuma G, Koster AJ, et al. Influence of aldehyde fixation on the morphology of endosomes and lysosomes: quantitative analysis and electron tomography. J Microsc. 2003;212:81–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2003.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmerman AE, Kells DI, Yip CC. Physical and biological properties of guinea pig insulin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972;46:2127–2133. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(72)90769-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caramia F, Munger BL, Lacy PE. The ultrastructural basis for the identification of cell types in the pancreatic islets. I. Guinea pig. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1965;67:533–546. doi: 10.1007/BF00342585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu X, Orci L, Carroll R, Norrbom C, Ravazzola M, Steiner DF. Severe block in processing of proinsulin to insulin accompanied by elevation of des-64,65 proinsulin intermediates in islets of mice lacking prohormone convertase 1/3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10299–10304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162352799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant PT, Coombs TL, Frank BH. Differences in the nature of the interaction of insulin and proinsulin with zinc. Biochem J. 1972;126:433–440. doi: 10.1042/bj1260433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orci L. The insulin factory: a tour of the plant surroundings and a visit to the assembly line. The Minkowski lecture 1973 revisited. Diabetologia. 1985;28:528–546. doi: 10.1007/BF00281987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanna ST, Pigeau GM, Galvanovskis J, Clark A, Rorsman P, MacDonald PE. Kiss-and-run exocytosis and fusion pores of secretory vesicles in human beta cells. Pflugers Arch. 2009;457:1343–1350. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0588-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noske AB, Costin AJ, Morgan GP, Marsh BJ. Expedited approaches to whole cell electron tomography and organelle mark-up in situ in high-pressure frozen pancreatic islets. J Struct Biol. 2008;161:298–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rorsman P, Trube G. Calcium and delayed potassium currents in mouse pancreatic beta cells under voltage-clamp conditions. J Physiol (Lond.) 1986;374:531–550. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Göpel S, Kanno T, Barg S, Galvanovskis J, Rorsman P. Voltage-gated and resting membrane currents recorded from B cells in intact mouse pancreatic islets. J Physiol (Lond.) 1999;521:717–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00717.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barg S, Galvanovskis J, Göpel SO, Rorsman P, Eliasson L. Tight coupling between electrical activity and exocytosis in mouse glucagon-secreting material alpha cells. Diabetes. 2000;49:1500–1510. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.9.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leung YM, Ahmed I, Sheu L, et al. Electrophysiological characterization of pancreatic islet cells in the mouse insulin promoter-green fluorescent protein mouse. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4766–4775. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howell SL. The molecular organization of the beta granule of the islets of Langerhans. Adv Cytopharmacol. 1974;2:319–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matthews EK, McKay DB, O'Connor MD, Borowitz JL (1982) Biochemical and biophysical characterization of insulin granules isolated from rat pancreatic islets by an iso-osmotic gradient. Biochim Biophys Acta 715 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Huang L, Shen H, Atkinson MA, Kennedy RT. Detection of exocytosis at individual pancreatic beta cells by amperometry at a chemically modified microelectrode. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9608–9612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Electron micrograph of an isolated pancreatic islet fixed by HPF. (a) The asterisk indicates a darker cell, conceivably an alpha cell, surrounded by lighter beta cells. Scale bar: 1 μm. (b) High magnification (2.2×) of (a) showing a granule near the Golgi complex with a halo (arrow 1) and a second with a protrusion resembling a small budding vesicle (arrow 2). To appreciate these details zooming into the on-line digital file is recommended. (c) High magnification (3.5×) of (a) showing several vesicles of various sizes near the plasma membrane and with a light electron dense matrix. These vesicles conceivably represent endosomes at different stages of reciprocal fusion and fission (PDF 5,562 kb)

Appearance of ISGs in chemically and HPF fixed INS-1 cells. Representative electron micrographs of INS-1 cells fixed either chemically (a) or with HPF (b) and embedded in Epon. The insets show a higher magnification of the areas marked with a dashed rectangle. (a) Scale bar in overview: 2 μm, in the inset: 100 nm. (b) Scale bar: 2 μm, magnification of the inset 3.1× of the original. (PDF 11,600 kb)

Electron micrograph of INS-1 cells fixed by HPF, embedded in Lowicryl HM20 and labelled for insulin. The inset shows a higher magnification (1.7×) of the area marked with a dashed rectangle. Scale bar on the bottom left corner: 100 nm (PDF 6,640 kb)

TSD of electron dense cores and ISGs fixed with HPF. (a–d) show the TSD of electron dense cores (a, b) and ISGs (c, d) in the first (a, c) and second (b, d) set of experimental sections. In both experiments based on HPF the size distributions of cores and ISGs are monomodal, in contrast to experiments based on chemical fixation (Fig. S5; PDF 89 kb)

TSD of chemically fixed electron dense cores and ISGs. (a–d) show the TSD of electron dense cores (a, b) and ISGs (c, d) in the first (a, c) and second (b, d) set of experimental sections. In both experiments based on chemical fixation the size distribution of cores is monomodal, while it is bimodal for ISGs in contrast to HPF fixation (Fig. S4; PDF 84 kb)

Distribution of major and minor axis. The experimentally measured distribution of the major (a) and minor (b) axes are shown for HPF fixed beta cells. The corresponding distributions from in silico slicing are shown in (c) and (d). Note that this distribution was generated starting from cells with variable size (PDF 82 kb)

The OSD of ISGs in HPF and chemically fixed beta cells. The OSD of ISGs resulting from experiments is shown in (a) for HPF and in (c) for chemically fixed beta cells. The corresponding differences of the experimental and in silico generated distributions are shown in (b) and (d); PDF 83 kb

Distribution of ISGs in beta cells. The apparent distance of ISGs from the PM in experiments is shown in (a) for HPF and in (c) for chemically fixed beta cells. The corresponding differences of the experimental and in silico generated distributions are shown in (b) and (d); PDF 67 kb

Dependency of various parameters on the number of slices. Values were normalised to those generated with 50,000 slices (PDF 73 kb)

PDF 52.4 kb

PDF 54.5 kb

PDF 52.6 kb

PDF 59.6 kb

PDF 110 kb