Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

To establish the occurrence, modulation and functional significance of compound exocytosis in insulin-secreting beta cells.

Methods

Exocytosis was monitored in rat beta cells by electrophysiological, biochemical and optical methods. The functional assays were complemented by three-dimensional reconstruction of confocal imaging, transmission and block face scanning electron microscopy to obtain ultrastructural evidence of compound exocytosis.

Results

Compound exocytosis contributed marginally (<5% of events) to exocytosis elicited by glucose/membrane depolarisation alone. However, in beta cells stimulated by a combination of glucose and the muscarinic agonist carbachol, 15–20% of the release events were due to multivesicular exocytosis, but the frequency of exocytosis was not affected. The optical measurements suggest that carbachol should stimulate insulin secretion by ∼40%, similar to the observed enhancement of glucose-induced insulin secretion. The effects of carbachol were mimicked by elevating [Ca2+]i from 0.2 to 2 μmol/l Ca2+. Two-photon sulforhodamine imaging revealed exocytotic events about fivefold larger than single vesicles and that these structures, once formed, could persist for tens of seconds. Cells exposed to carbachol for 30 s contained long (1–2 μm) serpentine-like membrane structures adjacent to the plasma membrane. Three-dimensional electron microscopy confirmed the existence of fused multigranular aggregates within the beta cell, the frequency of which increased about fourfold in response to stimulation with carbachol.

Conclusions/interpretation

Although contributing marginally to glucose-induced insulin secretion, compound exocytosis becomes quantitatively significant under conditions associated with global elevation of cytoplasmic calcium. These findings suggest that compound exocytosis is a major contributor to the augmentation of glucose-induced insulin secretion by muscarinic receptor activation.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00125-011-2400-5) contains peer-reviewed but unedited supplementary material, which is available to authorised users.

Keywords: Beta cell, Ca2+, Exocytosis

Introduction

Insulin is secreted from the pancreatic beta cells by Ca2+-dependent exocytosis [1]. Release of insulin is thought to involve the fusion of individual granules with the plasma membrane [2, 3]. High-resolution capacitance measurements have confirmed that most exocytotic events occur as the fusion of individual secretory granules [4]. However, about 10% of the exocytotic events were associated with larger stepwise increases in membrane capacitance [4] as if multiple granules fused simultaneously with the plasma membrane (compound exocytosis).

There are two types of compound exocytosis [5]. Sequential exocytosis starts with a primary fusion event at the plasma membrane, and other granules subsequently fuse with this granule. In multivesicular release, several granules first fuse within the cell before undergoing exocytosis as one unit. Sequential exocytosis has been reported in a variety of cells [6–9], including pancreatic beta cells [10, 11], but the significance of multivesicular release to insulin secretion remains unknown. Evidence for multivesicular release is particularly strong for electrically non-excitable cells [6, 7, 12], but recent data indicate that it also occurs in intensely stimulated neurons [13]. In pancreatic beta cells, ultrastructural evidence indicates that granules can prefuse within the cell under certain experimental conditions [14], but attempts to demonstrate multivesicular exocytosis by live cell imaging have produced conflicting results [10, 15, 16].

We have examined the occurrence of compound exocytosis in rat pancreatic beta cells by a combination of biophysical measurements, optical imaging and electron microscopy. Our data confirm that single-vesicle exocytosis is the predominant form of exocytosis in beta cells stimulated with glucose alone but that compound exocytosis becomes quantitatively significant under experimental conditions associated with global elevation of cytosolic Ca2+.

Methods

Islet isolation and cell culture

All experiments were conducted in accordance with the UK Animals Scientific Procedures Act (1986) and University of Oxford ethical guidelines. Pancreatic islets were isolated from Sprague–Dawley rats (Harlan, UK). For some experiments (see Figs 1, 2, 3, and 6), the islets were dissociated into single cells, plated on to plastic Petri dishes and maintained in short-term (up to 48 h) tissue culture as previously reported [17], whereas intact islets were used for the remaining experiments.

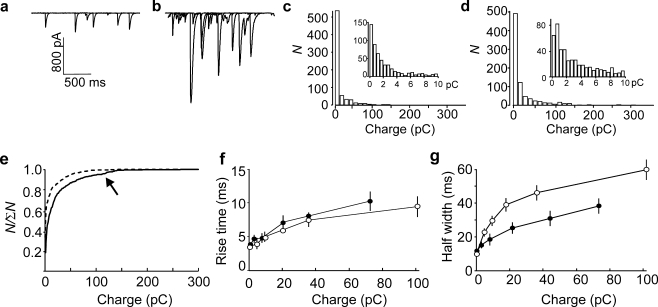

Fig. 1.

Small and large release events detected in single rat beta cells expressing P2X2Rs. a,b ATP-induced P2X2R current transients from rat beta cells infused with 0.2 (a) or 2 (b) μmol/l [Ca2+]i. Three sweeps have been superimposed in each panel. c,d Histograms of charge (Q) of ATP-induced P2X2R currents recorded at 0.2 (c) and 2 (d) μmol/l [Ca2+]i. Insets in c,d show events with Q-values <10 pC. e Cumulative distribution (N/∑N) of the integrated current (Q) of P2X2R current spikes measured from rat beta cells infused with 0.2 μmol/l (dashed line; 696 events) and 2 μmol/l (continuous line; 800 events) [Ca2+]i. Note inflection of curve obtained with the higher [Ca2+]i at ∼100 pC representing the subset of large events (arrow). f,g Relationship between the integrated P2X2R-mediated current (Q) and duration of the release events measured as t 10–90% (f) and halfwidths (g) of the current spikes recorded at 0.2 μmol/l (black circles) and 2 μmol/l (white circles) [Ca2+]i

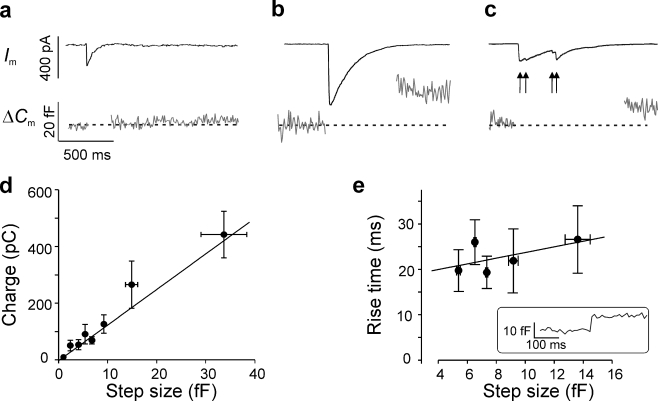

Fig. 2.

Large P2X2R events correlate with large increases in membrane capacitance in single rat beta cells. a,b Representative examples of parallel measurements of P2X2R currents (I m) and membrane capacitance (ΔC m) for small (a) and large (b) events. Note that the currents rise and fall monotonically. Activation of P2X2Rs results in large increases in membrane conductance that ‘leaks’ into the capacitance signal, and these parts of the experimental record have been removed. c As in a,b, but showing an example where a step increase in capacitance was associated with a series of discrete superimposed current spikes (arrows) reflecting exocytosis of individual granules. d Relationship between the integrated P2X2R-mediated current (Q) and the associated capacitance increase (ΔC m) in rat beta cells. The regression coefficient (r) was 0.79 (p < 0.001). e Relationship between size of capacitance steps (ΔC m) and time to reach the new plateau value recorded in non-transfected cells but conditions otherwise as in a–d. Inset shows an example of an exocytotic event with an amplitude of 18 fF (simultaneous fusion of five or six granules). Note that this analysis only includes large events and that events <4 fF (reflecting single exocytotic events) cannot be resolved during whole-cell recordings. For display purposes, individual data points have been grouped according to ΔC m in d and e (n = 48 and 47, respectively)

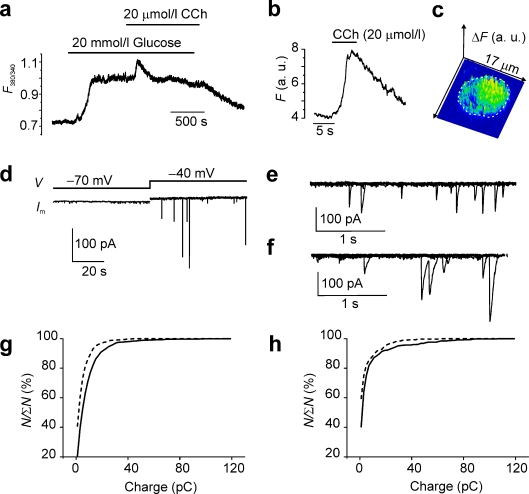

Fig. 3.

Carbachol-induced compound exocytosis in single rat beta cells. a Fura-2 measurements of [Ca2+]i in an intact rat islet stimulated with 20 mmol/l glucose and 20 μmol/l carbachol (CCh) as indicated by horizontal lines. b,c Fluo-5 recording of [Ca2+]i (F [in arbitrary units, a.u.]) in a rat beta cell exposed to 20 mmol/l glucose before and after addition of 20 μmol/l carbachol as indicated (b) and confocal (‘2.5D’) image of the same isolated rat beta cell showing the fluorescence increase (ΔF) evoked by application of 20 μmol/l carbachol (c) obtained by subtracting image immediately before addition of carbachol from that obtained at the peak (representative of five different cells). The dotted line in c indicates the circumference of the beta cell. d ATP release in rat beta cells (measured as activation of P2X2Rs) under control conditions (10 mmol/l glucose alone) when cell was held at −70 mV and after moderate depolarisation to −40 mV. Note stimulation of exocytosis seen as emergence of current transients. e,f ATP release measured at −40 mV in rat beta cells exposed to 10 mmol/l glucose in the absence (e) or presence (f) of 20 μmol/l carbachol. Several sweeps have been superimposed. g Cumulative distribution (N/ΣN) of charge (Q) recorded in the presence of 10 mmol/l glucose alone (dashed line; 836 events) and in the presence of 20 μmol/l carbachol (continuous line; 1,234 events). h As in g but after pretreatment of the cells with 20 μmol/l of the myristoylated CAMKII autoinhibitory peptide for 2 h (glucose: 448 events; glucose + carbachol: 603 events)

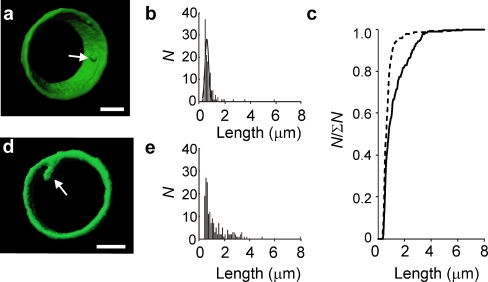

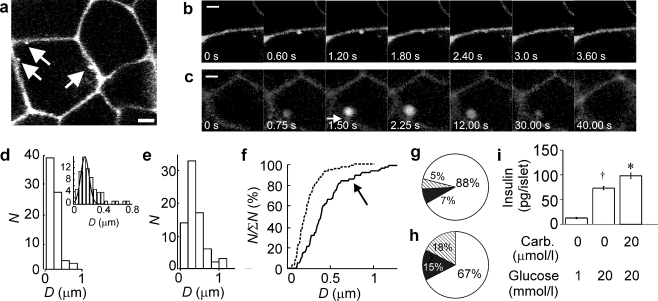

Fig. 6.

Multivesicular exocytosis detected by confocal imaging in isolated rat beta cells. a 3-D reconstruction of exocytotic events observed in rat beta cells captured during 30 s exposures to FM1-43FX in the presence of 20 mmol/l glucose alone. b Histogram of diameters/lengths of FM1-43FX-labelled structures in cells stimulated with 20 mmol/l glucose alone. A Gaussian curve with a peak at 0.60 μm has been superimposed on distribution. c Cumulative distribution of structures labelled by FM1-43FX in the presence of glucose alone (dashed line; n = 140 in 70 cells) and when combined with carbachol (continuous line; n = 176 in 40 cells). d As in a but showing an example of a large event observed in the simultaneous presence of 20 mmol/l glucose and 20 μmol/l carbachol. e As in b but showing histogram of diameters/lengths of FM1-43FX-labelled structures in cells stimulated with the combination of 20 mmol/l glucose and 2 μmol carbachol

P2X2 current and capacitance measurements

Parallel measurements of ATP release and change in membrane capacitance (ΔC m) were carried out using the standard whole-cell configuration as described previously [17]. Rat beta cells were infected with an adenoviral construct encoding a P2X purinoreceptor 2 (P2X2R)–green fluorescent protein fusion protein [17]. The membrane potential was, unless otherwise indicated, clamped at −70 mV. ΔC m was calculated by averaging the capacitance measurements 750 ms before and after a P2X2 current transient. For display, the current signal was filtered at 100 Hz to remove the sine wave. One series of experiments (see Fig. 3) was conducted using the perforated patch technique. In these experiments, the signal was filtered at 1 kHz and digitised at 2 kHz. In another series of experiments (see Fig. 2D), changes in cell capacitance were monitored in uninfected cells (i.e. cells not expressing P2X2Rs) to allow the time course of ATP release to be compared with the increase in membrane capacitance. In the latter measurements, the temporal resolution was 1 ms.

Two-photon imaging of exocytosis

Rat pancreatic islets were superfused with extracellular medium containing the fluorescent polar tracer, sulforhodamine (SRB; 0.7 mmol/l) [18, 19]. SRB was excited in the two-photon mode at 830 nm using a Chameleon laser (Coherent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Emitted light was collected through a Plan-Apochromat objective ×63/1.4 Oil (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) at 570–650 nm. The full-width-at-half-maximal fluorescence intensity of fluorescent spots recorded for microspheres (diameter 0.1–4.0 μm; TetraSpeck; Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) was measured and plotted against their actual size [20] to estimate actual diameters of objects represented by the spots in the SRB measurements (i.e. granules undergoing exocytosis). The diameters of the fluorescent dots were estimated from a circle fit into the pixels with intensity values equal to or greater than full-width-at-half-maximal fluorescence intensity. The temporal characteristics of exocytotic events were determined in regions of interest.

Insulin secretion

Insulin was determined by radioimmunoassay as described elsewhere [21]. Briefly, batches of eight to ten islets were preincubated in 1 ml Krebs Ringer bicarbonate buffer supplemented with 1 or 20 mmol/l glucose for 20 min followed by 1 min incubation in 1 ml Krebs Ringer bicarbonate buffer containing 1 or 20 mmol/l glucose and 20 mmol/l glucose plus 20 μmol/l carbachol. At the end of the incubation, aliquots of the medium were removed and frozen pending the radioimmunoassay.

Ca2+ microfluorimetry and imaging

Cytoplasmic free calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) in intact cells loaded with fura-2AM (1 μmol/l; Invitrogen) was monitored using a dual-wavelength Photon Technology International (Birmingham, NJ, USA) system [22]. Confocal images were obtained using an upright Zeiss 510 confocal microscope after loading of isolated rat beta cells maintained in tissue culture with fluo-5AM (1 μmol/l; Invitrogen) for 1 h. Excitation was at 488 nm, and emission measured at 510–540 nm.

FM1-43FX dye staining of exocytosis

Isolated rat beta cells were superfused with extracellular medium containing 20 mmol/l glucose supplemented or not with carbachol (20 μmol/l) for 30 s in the presence of 5 μg/ml FM1-43FX (Invitrogen). The extracellular solution was quickly removed, the dish washed to remove excess dye, and the cells finally fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C. Cells were scanned in 0.4 μm z-slices using a Zeiss 510 confocal microscope (excitation 488 nm; emission 515–550 nm).

Electron microscopy

Islets were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer for 1 h, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in methanol, and embedded in Epon 812 (Agar Scientific, Stansted, UK). Three-dimensional (3-D) electron micrographs (50 nm section thickness) were obtained by microtome-scanning block face electron microscopy [23]. Images were acquired on an FEI Quanta 200 VP-FEG electron microscope using an accelerating voltage of 4 keV and the low-vacuum mode (0.5 T) equipped with a microtome (3View; Gatan, Abingdon, UK). The contrasted specimen is cut inside the microscope. Every time the surface of the block is shaved off by a diamond knife, tissue is removed and the freshly cut surface of the block is scanned and an image is obtained. For transmission electron microscopy, ultrathin sections (80 nm) were cut on to Ni grids, contrasted with 2% uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined in a Jeol 1010 microscope (Welwyn Garden City, UK) with an accelerating voltage of 80 keV.

Solutions

The standard extracellular solution used in all imaging and electrophysiology experiments contained (mmol/l) 138 NaCl, 5.6 KCl, 2.6 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 5 d-glucose and 5 HEPES (pH 7.4 with NaOH). For the P2X2R experiments, the intracellular (pipette) solution consisted of (mmol/l) 125 CsCl, 10 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 5 or 9 CaCl2, 3 MgATP, 0.1 cAMP and 5 HEPES (pH 7.15 using CsOH). [Ca2+]i was estimated to be 0.2 and 2 μmol/l using the WIN MAXC32 2.5 computer program [24]. For the perforated patch recordings (see Fig. 3), the recording electrode contained (mmol/l) 76 K2SO4, 10 NaCl, 10 KCl, 1 MgCl2 and 5 HEPES (pH 7.35 with KOH). In the latter experiments, endogenous Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 2 (CAMKII) was inhibited by preincubating the cells for 2 h in the presence of 20 μmol/l of the myristoylated CAMKII autoinhibitory peptide (Biomol International, Exeter, UK).

Data analysis

Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Statistical significances of differences between means and distributions were estimated by Student’s t test or by Kolmogorov–Smirnov’s test (cumulative histograms). The 3-D reconstruction of the FM1-43FX events was performed using the Imaris 6.1.5 software (Bitplane Scientific Solutions, Zurich, Switzerland). The P2X2R-dependent current spikes were analysed using the Mini Analysis Program 6.0.3 (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA, USA). The confocal [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3B) and optical measurements of secretion (Figs 4 and 5) were analysed and presented using the software LSM Image Examiner. The numerical data of the exocytotic events thus measured were imported into MATLAB to determine the t 10–90% and half widths (HWs; Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Optical imaging of exocytosis in intact rat islets. a Two-photon excitation microscopy of an intact pancreatic islet perfused with an extracellular solution containing the fluorescent polar tracer SRB (0.7 mmol/l) and 20 mmol/l glucose. Scale bar: 3 μm. The three arrows indicate exocytotic events. b,c Example of a typical single event (b) and a large event (c) in the presence of 20 mmol/l glucose and 20 μmol/l carbachol. Scale bar: 1 μm. Images were taken at the indicated times (relative to the leftmost image). Note that the large event in c appears within the cell and is connected to the exterior by a stalk (dim fluorescence, arrow). d Histogram of diameters (D) of the fluorescent spots reflecting exocytosis in the presence of glucose. The inset shows the distribution on an expanded abscissa. A Gaussian curve with a mean value of 0.23 μm has been superimposed (102 events, 8 islets). e As in d but showing distribution after addition of 20 μmol/l carbachol (100 events, 8 islets). f The same data plotted as the cumulative distribution (N/∑N) of the diameters of exocytotic events evoked by 20 mmol/l glucose alone (dashed line) and 20 mmol/l glucose + 20 μmol/l carbachol (continuous line). Note inflection at ∼0.5 μm on distribution of events collected in the presence of carbachol (arrow). g,h Pie charts summarising relative frequency of single-vesicle (white), sequential (black) and multivesicular (hatched) exocytosis in beta cells within intact rat islets exposed to 20 mmol/l glucose with (h) or without (g) 20 μmol/l carbachol. The data were collected in 13 different islets and based on a total observation period of >3,100 s for each condition. i Insulin secretion measured in the presence of 1 or 20 mmol/glucose during a 1 min incubation. Carbachol (20 μmol/l; Carb.) was included as indicated. *p < 0.005 vs 20 mmol/l glucose alone; †p < 0.001 vs 1 mmol/l glucose

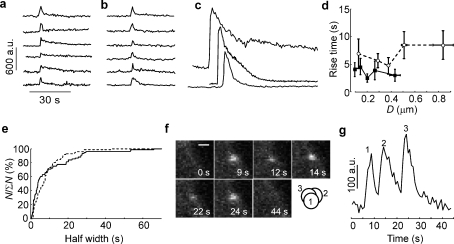

Fig. 5.

Kinetics of exocytosis in beta cells within intact rat pancreatic islets. a,b Examples of fluorescent intensity changes associated with events recorded in the presence of 20 mmol/l glucose alone (a) and in the simultaneous presence of glucose (20 mmol/l) and carbachol (20 μmol/l) (b) as indicated. c Examples of changes in fluorescence associated with the larger events observed in the presence of carbachol. Traces in a–c are shown using the same timebase and ordinate scales. d Relationship between diameter (D) of exocytotic events and rise time (t 10–90%) recorded in the presence of 20 mmol/l glucose alone (white circles) and after supplementation of medium with 20 μmol/l carbachol (black squares). For clarity, the individual data points have been grouped according to size. e Cumulative distribution (N/ΣN) of the rise times (t 10–90%) of the fluorescence increases associated with exocytosis observed in the presence of 20 mmol/l glucose alone (71 events in 7 islets; dashed line) and 20 mmol/l glucose plus 20 μmol/l carbachol (76 events in six islets; continuous line). f Montage of images during an example of sequential exocytosis in a rat beta cell exposed to 20 mmol/l glucose and 20 μmol/l carbachol. Images were taken at the indicated times (relative to the one in the upper left corner). Scale bar: 1 μm. The three circles in the lower right corner indicate the position of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd release events (expanded ×2.5) shown in the montage. Note that they occur in close proximity to each other but not in exactly the same place. g Time course of SRB fluorescence increase of events 1–3 shown in f. a.u., arbitrary units

Results

Magnitude of quantal ATP release increases in response to elevated [Ca2+]i

Insulin secretion is associated with ATP release [17]. Figure 1a,b shows examples of ATP-evoked currents (reflecting exocytosis) recorded from rat beta cells infected with P2X2Rs and infused with 0.2 or 2 μmol/l [Ca2+]i. These currents reflect activation of the P2X2Rs and are blocked by the purinergic antagonist, suramin [25]. At low [Ca2+]i, the events are infrequent and small (<300 pA). Elevation of [Ca2+]i to 2 μmol/l increases the frequency, amplitude and duration of these events. Figure 1c,d shows the histograms for the integrated currents (Q) of the events recorded at 0.2 and 2 μmol/l [Ca2+]i; non-Gaussian (skewed) distributions were obtained under both experimental conditions (see electronic supplementary material [ESM] text, section 1). Whereas most events recorded at low [Ca]i were smaller than 5 pC, ∼55% of the events recorded at 2 μmol/l [Ca2+]i were larger than 5 pC. The corresponding cumulative histograms are shown in Fig. 1e. The distribution of the Q of exocytotic events was shifted to the right when [Ca2+]i was elevated from 0.2 to 2 μmol/l (p < 0.001).

Figure 1f shows the relationship between charge and the t 10-90% and HW. The t 10-90% values were <10 ms over a wide range of Q. By contrast, the HWs increased with the event size: from ∼10 ms for small events to ∼40 ms for events >50 pC (Fig. 1g). A longer duration of the ATP-induced P2X2R current would be consistent with the emptying of an enlarged granule lumen, which may result if several granules combine within the cell and then fuse with the plasma membrane as one unit (multivesicular exocytosis) or rapid sequential exocytosis emptying via a single fusion pore.

If multivesicular exocytosis occurs, then there should be a correlation between the Q and the amount of membrane added (measured as ΔC m). Figure 2a,b shows examples of events associated with small and large P2X2R currents and parallel ΔC m in rat beta cells dialysed with 0.2 μmol/l [Ca2+]i. In both cases, the ATP-evoked whole-cell currents rose and decayed monotonically with no sign of superimpositions of discrete events. Statistical analysis suggests that it is highly unlikely that these events result from superimposition of multiple smaller events (ESM text, section 2). For comparison, Fig. 2c shows an example where a step capacitance increase of ∼10 fF is associated with four discrete spikes that are superimposed. Thus we can estimate that each release event adds ∼2.5 fF of capacitance, close to the 2.9 fF measured by on-cell capacitance measurements [26]. Figure 2d shows the relationship between ΔC m and Q (only including events without signs of superimpositions). The largest steps averaged ∼35 fF, corresponding to the simultaneous fusion of more than ten granules with the plasma membrane.

It would appear that the increase in capacitance (reflecting the fusion of the granules with the plasma membrane) should precede the emptying of the granules (detected as the activation of the P2X2Rs). However, intragranular ATP is highly mobile and exits promptly upon membrane fusion, even before complete expansion of the fusion pore [26–29]. It is accordingly not possible to temporally dissociate the capacitance increase from ATP release. Indeed, the capacitance steps recorded in beta cells not infected with P2X2Rs exhibited a kinetics (rise time ∼20 ms; Fig. 2e) that was, if anything, slower than that of the events recorded with the P2X2R-based assay (cf. Fig. 1f). It can also be noted, however, that the large ΔC m steps develop with a time course only marginally slower than that seen for the small steps, a feature not consistent with the notion that they result from rapid sequential exocytosis of individual secretory granules.

Carbachol stimulates compound exocytosis in rat beta cells

The findings of Fig. 1 indicate that a global elevation of [Ca2+]i (by intracellular dialysis via the recording electrode) promotes multivesicular release. Acetylcholine stimulates insulin secretion by activation of muscarinic M3 receptors [30] and enhances insulin release through a combination of several effects [31] including activation of protein kinase C (PKC) and inositol trisphosphate (IP3)-dependent mobilisation of intracellular Ca2+ [32, 33]. Figure 3a shows changes in [Ca2+]i evoked by 20 mmol/l glucose alone and after addition of 20 μmol/l carbachol in an intact rat pancreatic islet. Glucose produces a non-oscillatory elevation of [Ca2+]i, and carbachol elicits a transient further elevation. We confirmed by confocal imaging of [Ca2+]i (in agreement with previous reports [34]) that carbachol elicited a widespread increase in [Ca2+]i in the cell centre (Fig. 3b,c).

We monitored exocytosis before and after the addition of 20 μmol/l carbachol to individual rat beta cells infected with P2X2Rs using the perforated patch whole-cell technique. The cells were exposed to 10 mmol/l glucose and the membrane potential initially held at −70 mV to keep the voltage-gated Ca2+ channels closed. Under these conditions, the rate of exocytosis was low, and P2X2R currents not observed. Depolarisation to −40 mV resulted in sufficient activation of the Ca2+ channels to initiate exocytosis (Fig. 3d). Figure 3e,f shows examples of the P2X2R currents elicited at −40 mV in the presence of glucose alone and after addition of carbachol. It is evident that addition of carbachol increases the amplitude and duration of the events, but their frequency was not affected (0.22 ± 0.05 events/s and 0.17 ± 0.04 events/s in the absence and presence of carbachol, respectively). The cumulative histograms of Q in the absence and presence of carbachol are shown in Fig. 3g. The distribution was shifted to the right in the presence of 20 μmol/l carbachol (p < 0.001). The effects of carbachol cannot be attributed to changes in the gating of the P2X2R currents; the integrated current evoked by application of 30 μmol/l ATP in the presence of 20 μmol/l carbachol averaged 101 ± 8% (n = 4) of that evoked in the absence of the agonist. The effect of carbachol was not mimicked by application of the PKC activator phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; 162 nmol/l, not shown), was insensitive to the PKC inhibitor chelerythrine (1.3 μmol/l; not shown), but partially antagonised by pretreatment of the cells with 20 μmol/l the myristoylated CAMKII autoinhibitory peptide (Fig. 3h).

Optical imaging of multivesicular exocytosis in beta cells in intact islets

We investigated the occurrence of multivesicular exocytosis in beta cells within intact pancreatic islets using SRB imaging. Figure 4a shows a region of an islet exposed to 20 mmol/l glucose. Exocytotic events were identified as the rapid appearance of fluorescent spots with a diameter of >0.15 μm that are easily distinguished from endocytotic events, most of which have diameters of <0.08 μm [35, 36]. The arrows highlight three exocytotic events. The islet was subsequently exposed to 20 μmol/l carbachol in the continued presence of 20 mmol/l glucose. Figure 4b,c shows magnified views of small and large events observed during carbachol stimulation. The larger event appeared within the cell and seemed connected to the extracellular space via a stalk of dim fluorescence.

The distribution of the corrected diameters of the fluorescent spots seen in the presence of glucose alone and in the simultaneous presence of glucose and carbachol are shown in Fig. 4d,e. The events evoked by 20 mmol/l glucose alone had a diameter of 0.23 ± 0.02 μm, in reasonable agreement with that estimated for insulin granules by electron microscopy [37]. The cumulative distributions of the diameters observed at 20 mmol/l glucose alone and after supplementation of the medium with 20 μmol/l carbachol are shown in Fig. 4f; the distribution is shifted to the right in the presence of carbachol (p < 0.001). In the presence of carbachol, 15% of the events were larger than any of the events observed in the presence of glucose. The diameter of this subgroup of events averaged 1.20 ± 0.23 μm, 5.2-fold larger than the average of the events evoked by glucose alone. The frequency of exocytosis increase averaged 2.4 events/min per islet in both the absence and presence of carbachol in islets exposed to 20 mmol/l glucose (not shown). However, the fraction of events that were of the compound type increased >3.5-fold, from 5% in the presence of 20 mmol/l glucose alone (Fig. 4g) to 18% after addition of 20 μmol/l carbachol (Fig. 4h). In islets exposed to 20 mmol/l glucose, a 1 min stimulation with 20 μmol/l carbachol stimulated insulin secretion by 35% (Fig. 4i). The corresponding stimulation measured over 20 min averaged 49% (not shown). In islets exposed to 1 mmol/l glucose throughout, insulin secretion was <20% of that seen in the presence of glucose.

Representative recordings of the SRB fluorescence changes in the presence of glucose alone and when the medium was supplemented with carbachol are shown in Fig. 5a,b. Most events recorded in the presence of carbachol were of the same size as those observed with glucose alone. Occasionally, however, much larger events were observed (Fig. 5c). These large events increased monotonically without any irregularities suggestive of smaller events being superimposed. The relationship between the diameter of the event and the rise times is shown in Fig. 5d. Under control conditions (20 mmol/l glucose), the rise times of events averaged 3.9 ± 0.6 s and did not vary much with the diameter. In the presence of carbachol, events with a diameter of <0.4 μm (similar to those evoked by glucose alone) had a mean rise time of 5.10 ± 1.20 s. However, for larger events the rise time increased to 9.1 ± 1.6 s (p < 0.001 vs all events at 20 mmol/l glucose alone). Possible reasons why the rise times reported by the SRB imaging are ∼1,000-fold longer than those indicated by the measurements of ATP release are discussed in the ESM text (section 3). In contrast, the HW of the events was constant over a wide range of spot areas (not shown). Notably, 15% of the events have HWs >20 s and required >30 s to return to the baseline (Fig. 5e).

In addition to multivesicular exocytosis, we also observed examples of sequential exocytosis that took place in rapid succession (10 s) within the same part of the beta cell and almost returned to baseline before the next event (Fig. 5f). These events were easily distinguished from the multivesicular events in displaying temporally well-separated stepwise increases in fluorescence (Fig. 5g); 7% of the events were of this type in islets exposed to 20 mmol/l glucose alone, which increased to 15% in the presence of carbachol (Fig. 4h).

Multivesicular and single-vesicle exocytosis imaged with FM1-43FX

We used the fixable fluorescent styryl dye FM1-43FX [38] to study exocytosis in rat beta cells. This dye cannot cross membranes and only labels membranes in direct contact with the extracellular solution. The cells were exposed to either 20 mmol/l glucose alone or in combination with 20 μmol/l carbachol (for 30 s). The FM1-43FX dye was present only during the last 30 s. Previous observations [18, 39] and the present live cell imaging of exocytosis (Fig. 5e) suggest that many of the release events have sufficiently long lifetimes to be captured by this protocol. Figure 6a shows a 3-D reconstruction of the most common type of structures labelled in the presence of 20 mmol/l glucose alone (ESM Movie 1). Figure 6b summarises the distribution of the length/diameter of these structures labelled by FM1-43FX in cells exposed to glucose alone; the distribution was nearly Gaussian with a mean of 0.60 ± 0.05 μm (n = 140). Fluorescent beads with a diameter of 0.20 μm (i.e. similar to the 0.3 μm diameter of insulin granules in rat beta cells [40]) had a measured diameter of 0.50 ± 0.02 μm (n = 12). The cumulative distribution of these events is shown as the dashed line in Fig. 6c. In cells exposed to carbachol for 30 s (Fig. 6d), >15% of the structures labelled by FM1-43FX were larger than ≥2 μm. In islets exposed to 20 mmol/l glucose alone, the corresponding number was <5%. A 3-D reconstruction of one of the large events is shown in Fig. 6d (ESM Movie 2) that remain connected to the cell surface. In many cases, these exhibited a serpentine-like morphology (hence these data are quoted as lengths rather than diameters). These events are too big to represent endocytotic vesicles (diameter = 70–80 nm [35, 36, 41]). The cumulative distribution of the FM1-43FX-labelled structures in cells exposed to glucose in the presence of carbachol is shown as the continuous line in Fig. 6c. The distribution of the events was shifted to the right in the presence of carbachol (p < 0.001).

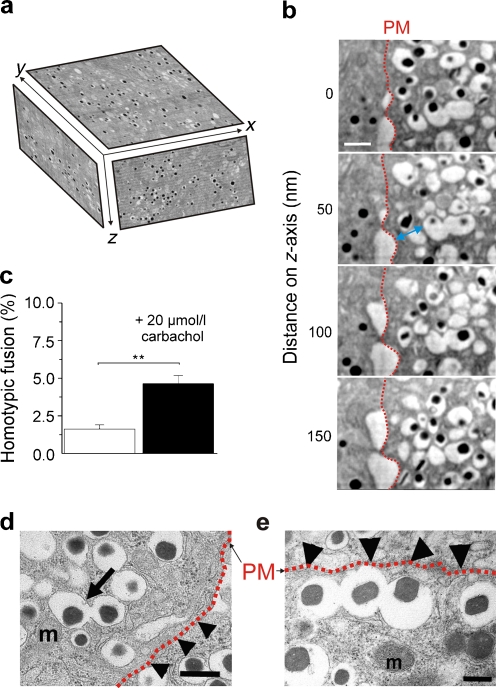

3-D scanning electron microscopy ultrastructural analysis of intact rat islets

We examined whether carbachol increases the prevalence of homotypically fused granules within the cytosol by serial scanning electron microscopy [23]. Figure 7a shows an xy plane of a beta cell together with 3-D rendered xz and yz planes. Regardless of whether the islets had been treated with carbachol or not, most granules were not connected. However, occasionally prefused multigranular structures were observed (Fig. 7b). On average, carbachol increased the number of homotypically fused granules threefold; in the presence of carbachol, 4% of the granules were joined to at least another granule (Fig. 7c). The largest number of fused granules observed was six. The example shown was within ∼400 nm of the plasma membrane. In cells exposed to carbachol, the average distance between the multivesicular structure and the plasma membrane averaged 1 ± 0.2 μm, with about one-third residing within one granule diameter (0.3–0.4 μm) of the plasma membrane. We confirmed the occurrence of multivesicular complexes using transmission electron microscopy, which allows more unequivocal identification of the granule membranes. These experiments provided additional evidence of connected granules (Fig. 7d,e), occasionally adjacent to the plasma membrane.

Fig. 7.

Ultrastructural evidence for multigranular structures in beta cells captured by 3-D and two-dimensional electron microscopy in the presence of glucose or glucose plus the cholinergic agonist carbachol in intact islets. a Schematic representation of a 3-D block of a serially sectioned rat pancreatic islet. b Serial sections of a single beta cell exposed to the cocktail of glucose (20 mmol/l) and carbachol (20 μmol/l; 5 min). Images illustrate a group of homotypically fused granules with connected cores. Note that the captured multivesicular complex is approximately one granule diameter (blue double-headed arrow) from the plasma membrane (PM, red dotted line). Section thickness: 50 nm. Scale bar: 0.4 μm. c The percentage of homotypically fused granules relative to the total number of granules observed within the cytosol of four complete beta cells using the 3-D electron microscopic images in 20 mmol/l glucose alone (n = 3,338 granules) and when medium was supplemented with 20 μmol/l carbachol (n = 4,580 granules); **p < 0.01. d,e Transmission electron microscopy (two-dimensional) examples of two individual multigranular structures in a rat beta cell exposed to 20 mmol/l glucose in the presence (d) and absence (e) of 20 μmol/l carbachol. Note that in e the multivesicular structure aligns below the plasma membrane (cf. Fig. 6d). The frequency of multivesicular structures was 0.18% (seven compound and 2,712 single events) and 0.37% (16 compound and 4,094 single events) in the absence and presence of carbachol, respectively. Data were from ≥25 cells for both experimental conditions. The plasma membrane (PM) is indicated by the dotted red lines and arrow heads. Scale bars: 0.5 μm in d and 0.2 μm in e. A few mitochondria (m) are indicated

Discussion

Our data confirm previous observations [10] that compound multivesicular exocytosis contributes marginally (<5%) to glucose-induced insulin secretion. However, multivesicular compound exocytosis of prefused granules becomes quantitatively significant in the presence of carbachol and then accounts for up to 18% of the events (Figs 4, 5).

We believe that the large P2X2R-dependent currents and capacitance steps reflect exocytosis of granules that have prefused within the cell before fusing with the plasma membrane rather than individual granules fusing with each other in rapid succession. This conclusion is underpinned by the following observations. First, in the P2X2R-based assay, the large events described here developed monotonically and there was no sign of any discrete steps that could reflect exocytosis of single granules in rapid succession. Second, the two-photon imaging experiments indicated the occurrence of large exocytotic events that rose without discernible steps of the type seen during sequential exocytosis (compare Fig 5c and g). Third, confocal imaging of FM1-43FX enabled the identification of large serpentine-like structures in beta cells (Fig. 6d) that had been exposed to carbachol and fixed within the lifetime of the large events determined by the two-photon SRB imaging experiments (Fig. 5c,e).

The dearth of multivesicular complexes reported by the ultrastructural analyses (Fig. 7) compared with the functional measurements indicates that they form shortly before their fusion with the plasma membrane, making them difficult to capture by electron microscopy. In this context, it should be remembered that only a small fraction of the insulin granules undergo exocytosis (0.1%/20 min), making it difficult to correlate the ultrastructural and functional data.

Is multivesicular exocytosis functionally significant? Consider (for didactic reasons) a beta cell with 100 release sites. If single granules undergo exocytosis at these sites, then a total of 120 granule equivalents will undergo exocytosis in the presence of 20 mmol/l glucose alone (five multivesicular events comprising five granules and 95 unitary events; i.e. 5 × 5 + 95 × 1 granule equivalents). However, in the presence of carbachol, multivesicular exocytosis will occur at 18 of these release sites, and a total of 172 granule equivalents will be released (i.e. 82 × 1 + 18 × 5). This stimulation of 43% is comparable to the 35–49% stimulation of insulin secretion evoked by carbachol during 1–20 min exposures (Fig. 4i), similar to the stimulation previously reported by others [42]. Thus the stimulation of insulin secretion by carbachol appears largely attributable to an increase in compound exocytosis rather than the frequency. In contrast, agents that increase cAMP (such as glucagon-like peptide 1 [GLP-1]) also increase the frequency of exocytosis [15, 43].

What would be the functional significance of compound and sequential exocytosis in the beta cell? We think that the low Ca2+-channel density (0.9 μm−2) [44], much lower than that reported for chromaffin cells (9–20 μm−2) [45, 46], provides a clue. Despite their low Ca2+-channel density, pancreatic beta cells are capable of a remarkably high rate of exocytosis, which approaches that in chromaffin cells. Reported maximum rates of capacitance increase (1.2 pF/s [32, 44]) correspond to 300 vesicles being released per second. In compound (as well as sequential) exocytosis, Ca2+ influx via a single Ca2+ channel may suffice to deliver several granules worth of cargo into the islet interstitium using a single fusion site. Such a mechanism may be functionally significant under physiological conditions when insulin demand is very high.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 86 kb)

The commonest type of event observed in the FM1-43FX-labelling experiments in single rat beta cells exposed to 20 mmol/l glucose alone. A snapshot of this movie is shown in Fig. 6a (AVI 444 kb)

Example of an event observed in the FM1-43FX-labelling experiments in single rat beta cells exposed to 20 mmol/l glucose and 20 μmol/l carbachol. A snapshot of this movie is shown in Fig. 6d (AVI 1,394 kb)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (095331/Z/11/Z). M. B. Hoppa’s DPhil studentship at the University of Oxford was funded by the European Union Integrated Project grant Eurodia.

Contribution statement

All authors participated in the conception and design, or analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. They all read, commented on and approved the final version to be published.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- CAMKII

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 2

- [Ca2+]i

Cytoplasmic free calcium concentration

- ΔCm

Change in membrane capacitance

- HW

Half width (time during which current exceeds 50% of the peak value)

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- P2X2R

P2X purinoreceptor 2

- Q

Charge (integrated current)

- SRB

Sulforhodamine

- 3-D

Three-dimensional

- t10–90%

Rise time (time it takes for current to increase from 10% to 90% of peak value)

References

- 1.Rorsman P, Renstrom E. Insulin granule dynamics in pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1029–1045. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Straub SG, Shanmugam G, Sharp GW. Stimulation of insulin release by glucose is associated with an increase in the number of docked granules in the beta-cells of rat pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 2004;53:3179–3183. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohara-Imaizumi M, Fujiwara T, Nakamichi Y, et al. Imaging analysis reveals mechanistic differences between first- and second-phase insulin exocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:695–705. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanna ST, Pigeau GM, Galvanovskis J, Clark A, Rorsman P, MacDonald PE. Kiss-and-run exocytosis and fusion pores of secretory vesicles in human beta-cells. Pflugers Arch. 2009;457:1343–1350. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0588-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pickett JA, Edwardson JM. Compound exocytosis: mechanisms and functional significance. Traffic. 2006;7:109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvarez de Toledo G, Fernandez JM. Compound versus multigranular exocytosis in peritoneal mast cells. J Gen Physiol. 1990;95:397–409. doi: 10.1085/jgp.95.3.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hafez I, Stolpe A, Lindau M. Compound exocytosis and cumulative fusion in eosinophils. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44921–44928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306013200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cochilla AJ, Angleson JK, Betz WJ. Differential regulation of granule-to-granule and granule-to-plasma membrane fusion during secretion from rat pituitary lactotrophs. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:839–848. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.4.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nemoto T, Kimura R, Ito K, et al. Sequential-replenishment mechanism of exocytosis in pancreatic acini. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:253–258. doi: 10.1038/35060042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi N, Hatakeyama H, Okado H, et al. Sequential exocytosis of insulin granules is associated with redistribution of SNAP25. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:255–262. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orci L, Malaisse W. Hypothesis: single and chain release of insulin secretory granules is related to anionic transport at exocytotic sites. Diabetes. 1980;29:943–944. doi: 10.2337/diab.29.11.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lollike K, Lindau M, Calafat J, Borregaard N. Compound exocytosis of granules in human neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:973–980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He L, Xue L, Xu J, et al. Compound vesicle fusion increases quantal size and potentiates synaptic transmission. Nature. 2009;459:93–97. doi: 10.1038/nature07860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahl G, Henquin JC. Cold-induced insulin release in vitro: evidence for exocytosis. Cell Tissue Res. 1978;194:387–398. doi: 10.1007/BF00236160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwan EP, Gaisano HY. Glucagon-like peptide 1 regulates sequential and compound exocytosis in pancreatic islet beta-cells. Diabetes. 2005;54:2734–2743. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takahashi N, Kasai H. Exocytic process analyzed with two-photon excitation imaging in endocrine pancreas. Endocr J. 2007;54:337–346. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.KR-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karanauskaite J, Hoppa MB, Braun M, Galvanovskis J, Rorsman P. Quantal ATP release in rat beta-cells by exocytosis of insulin-containing LDCVs. Pflugers Arch. 2009;458:389–401. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0610-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takahashi N, Nemoto T, Kimura R, et al. Two-photon excitation imaging of pancreatic islets with various fluorescent probes. Diabetes. 2002;51(Suppl 1):S25–S28. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.S25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Obermuller S, Calegari F, King A et al. Defective secretion of islet hormones in chromogranin-B deficient mice. PLoS ONE 5:e8936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Kasai H, Hatakeyama H, Kishimoto T, Liu TT, Nemoto T, Takahashi N. A new quantitative (two-photon extracellular polar-tracer imaging-based quantification (TEPIQ)) analysis for diameters of exocytic vesicles and its application to mouse pancreatic islets. J Physiol. 2005;568:891–903. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.093047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braun M, Ramracheya R, Bengtsson M, et al. Voltage-gated ion channels in human pancreatic beta-cells: electrophysiological characterization and role in insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2008;57:1618–1628. doi: 10.2337/db07-0991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olofsson CS, Gopel SO, Barg S, et al. Fast insulin secretion reflects exocytosis of docked granules in mouse pancreatic B cells. Pflugers Arch. 2002;444:43–51. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0781-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denk W, Horstmann H. Serial block-face scanning electron microscopy to reconstruct three-dimensional tissue nanostructure. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patton C, Thompson S, Epel D. Some precautions in using chelators to buffer metals in biological solutions. Cell Calcium. 2004;35:427–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obermuller S, Lindqvist A, Karanauskaite J, Galvanovskis J, Rorsman P, Barg S. Selective nucleotide-release from dense-core granules in insulin-secreting cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4271–4282. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacDonald PE, Braun M, Galvanovskis J, Rorsman P. Release of small transmitters through kiss-and-run fusion pores in rat pancreatic beta cells. Cell Metab. 2006;4:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacDonald PE, Rorsman P. The ins and outs of secretion from pancreatic beta-cells: control of single-vesicle exo- and endocytosis. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:113–121. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00047.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun M, Wendt A, Karanauskaite J, et al. corelease and differential exit via the fusion pore of GABA, serotonin, and ATP from LDCV in rat pancreatic beta cells. J Gen Physiol. 2007;129:221–231. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galvanovskis J, Braun M, Rorsman P. Exocytosis from pancreatic β-cells: mathematical modelling of the exit of low-molecular-weight granule content. Interface Focus. 2011;1:143–152. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2010.0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gautam D, Han SJ, Hamdan FF, et al. A critical role for beta cell M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in regulating insulin release and blood glucose homeostasis in vivo. Cell Metab. 2006;3:449–461. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilon P, Henquin JC. Mechanisms and physiological significance of the cholinergic control of pancreatic beta-cell function. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:565–604. doi: 10.1210/er.22.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ammala C, Eliasson L, Bokvist K, Larsson O, Ashcroft FM, Rorsman P. Exocytosis elicited by action potentials and voltage-clamp calcium currents in individual mouse pancreatic B cells. J Physiol. 1993;472:665–688. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bokvist K, Eliasson L, Ammala C, Renstrom E, Rorsman P. Co-localization of L-type Ca2+ channels and insulin-containing secretory granules and its significance for the initiation of exocytosis in mouse pancreatic B cells. EMBO J. 1995;14:50–57. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb06974.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Theler JM, Mollard P, Guerineau N, et al. Video imaging of cytosolic Ca2+ in pancreatic beta-cells stimulated by glucose, carbachol, and ATP. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18110–18117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kasai H, Kishimoto T, Nemoto T, Hatakeyama H, Liu TT, Takahashi N. Two-photon excitation imaging of exocytosis and endocytosis and determination of their spatial organization. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:850–877. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacDonald PE, Eliasson L, Rorsman P. Calcium increases endocytotic vesicle size and accelerates membrane fission in insulin-secreting INS-1 cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5911–5920. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacDonald PE, Obermuller S, Vikman J, Galvanovskis J, Rorsman P, Eliasson L. Regulated exocytosis and kiss-and-run of synaptic-like microvesicles in INS-1 and primary rat beta-cells. Diabetes. 2005;54:736–743. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.3.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Angleson JK, Cochilla AJ, Kilic G, Nussinovitch I, Betz WJ. Regulation of dense core release from neuroendocrine cells revealed by imaging single exocytic events. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:440–446. doi: 10.1038/8107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michael DJ, Ritzel RA, Haataja L, Chow RH. Pancreatic beta-cells secrete insulin in fast- and slow-release forms. Diabetes. 2006;55:600–607. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.03.06.db05-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braun M, Wendt A, Birnir B, et al. Regulated exocytosis of GABA-containing synaptic-like microvesicles in pancreatic beta-cells. J Gen Physiol. 2004;123:191–204. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hatakeyama H, Takahashi N, Kishimoto T, Nemoto T, Kasai H. Two cAMP-dependent pathways differentially regulate exocytosis of large dense-core and small vesicles in mouse beta-cells. J Physiol. 2007;582:1087–1098. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Persaud SJ, Jones PM, Sugden D, Howell SL. The role of protein kinase C in cholinergic stimulation of insulin secretion from rat islets of Langerhans. Biochem J. 1989;264:753–758. doi: 10.1042/bj2640753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kasai H, Suzuki T, Liu TT, Kishimoto T, Takahashi N. Fast and cAMP-sensitive mode of Ca2+-dependent exocytosis in pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes. 2002;51(Suppl 1):S19–S24. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barg S, Ma X, Eliasson L, et al. Fast exocytosis with few Ca2+ channels in insulin-secreting mouse pancreatic B cells. Biophys J. 2001;81:3308–3323. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75964-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fenwick EM, Marty A, Neher E. Sodium and calcium channels in bovine chromaffin cells. J Physiol. 1982;331:599–635. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klingauf J, Neher E. Modeling buffered Ca2+ diffusion near the membrane: implications for secretion in neuroendocrine cells. Biophys J. 1997;72:674–690. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78704-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 86 kb)

The commonest type of event observed in the FM1-43FX-labelling experiments in single rat beta cells exposed to 20 mmol/l glucose alone. A snapshot of this movie is shown in Fig. 6a (AVI 444 kb)

Example of an event observed in the FM1-43FX-labelling experiments in single rat beta cells exposed to 20 mmol/l glucose and 20 μmol/l carbachol. A snapshot of this movie is shown in Fig. 6d (AVI 1,394 kb)