Abstract

Protein function often requires large-scale domain motion. An exciting new development in the experimental characterization of domain motions in proteins is the application of neutron spin-echo spectroscopy (NSE). NSE directly probes coherent (i.e., pair correlated) scattering on the ∼1–100 ns timescale. Here, we report on all-atom molecular-dynamics (MD) simulation of a protein, phosphoglycerate kinase, from which we calculate small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) and NSE scattering properties. The simulation-derived and experimental-solution SANS results are in excellent agreement. The contributions of translational and rotational whole-molecule diffusion to the simulation-derived NSE and potential problems in their estimation are examined. Principal component analysis identifies types of domain motion that dominate the internal motion's contribution to the NSE signal, with the largest being classic hinge bending. The associated free-energy profiles are quasiharmonic and the frictional properties correspond to highly overdamped motion. The amplitudes of the motions derived by MD are smaller than those derived from the experimental analysis, and possible reasons for this difference are discussed. The MD results confirm that a significant component of the NSE arises from internal dynamics. They also demonstrate that the combination of NSE with MD is potentially useful for determining the forms, potentials of mean force, and time dependence of functional domain motions in proteins.

Introduction

The conformational dynamics of proteins, and in particular large-scale domain motions, are often essential for their biological function. Few experimental techniques are available that can directly probe collective protein dynamics, i.e., that can provide quantitatively interpretable results without requiring the use of perturbing labels and/or prior assumptions as to the underlying nature of the dynamics. However, because of the simplicity of the neutron-nucleus interaction, dynamic neutron scattering can serve as a direct probe, and scattering intensities can be calculated from appropriate correlation functions of the atomic positions. This closely relates dynamic neutron scattering to molecular-dynamics (MD) simulation because, in principle, the scattering functions can be calculated from MD trajectories without significant approximations.

Investigators have combined MD with incoherent dynamic neutron scattering to analyze protein dynamics since 1986 (1–4). Early neutron and simulation studies on proteins focused on picosecond-timescale harmonic vibrational collective internal dynamics and provided the first experimental determination of the distribution of low-frequency vibrational modes in a protein (5,6). Further, it was shown that the vibrational densities of states change upon ligand binding to a protein (methotrexate to dihydrofolate reductase) and contribute significantly to the binding free energy (7–9).

Anharmonic dynamics has been investigated in particular with reference to the ∼200 K temperature-dependent transition in protein dynamics, which resembles the glass transition (10). This dynamical transition is also present in MD simulations (11), and the simulation-and-neutron combination has been used to characterize dynamical transition phenomena in detail (12–16). MD has also been used to examine approximations commonly used in the derivation of mean-square displacements from neutron experiments (13), as well as to decompose the contributions to experimental timescale-dependent spectra (14,17). Researchers have also used MD simulations to characterize how solvent molecules drive the dynamical transition (16,18–21). Further, an MD-based principal component analysis (PCA) of the dynamical transition revealed that the essential motions thus activated can be represented as a very small number of collective coordinates (15).

Neutron experiments and simulations have also been combined to characterize picosecond-timescale diffusive internal protein dynamics at physiological temperatures (22–24). An early analysis showed that rigid-body side-chain dynamics dominates picosecond-timescale protein quasielastic intensities (25), and a complementary radially softening description of the internal protein motion was developed (26). The diffusive coordinate motion can also be described as anomalous subdiffusion originating from the fractal-like structure of configuration space (27). However, so far, the limited energy resolution of time-of-flight and backscattering spectrometers has precluded the quantitative study of interdomain motions. These motions include classic hinge-bending dynamics proposed in the 1970s for lysozyme (28), phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) (29–31), and other proteins. A data bank for ligand-induced domain motions has now been established (32).

Correlated motions are manifest in x-ray diffuse scattering from protein crystals, and diffuse scattering measured from orthorhombic lysozyme crystals was found to closely resemble the patterns calculated from molecular simulation (33,34). The contribution of functional correlated fluctuations in crystalline Staphylococcal nuclease to x-ray diffuse scattering was also demonstrated by simulation (35). An all-atom lattice dynamical calculation of a protein crystal was reported (36), and it is hoped that this will lead to corresponding triple-axis phonon dispersion experiments, although technical challenges are involved. However, the crystalline state can hinder large-scale domain motions and, furthermore, the energy resolution of x-ray scattering is necessary to determine associated timescales (37,38). Thus, solution neutron scattering is arguably better suited to this purpose.

The studies cited above concentrated on incoherent inelastic and quasielastic neutron scattering, which probes self-correlations of atom positions and motions, especially of hydrogen atoms, in proteins on timescales of ∼10−14–10−10 s. The results provided physical insights into the energy landscapes of proteins, and phenomena related to the glass transition. However, correlated functional protein motions are often active on timescales of nanoseconds and longer. For this reason, the advent of the application of neutron spin-echo spectroscopy (NSE) to protein dynamics is particularly promising.

NSE extends the timescale for which neutron scattering can be applied to proteins to the ∼100 ns domain (39–44) in the coherent scattering regime at small scattering vectors. Recently, it was unequivocally demonstrated that NSE, which hitherto has been mostly applied to determine polymer dynamics, can directly detect internal collective protein dynamics. NSE allows the simultaneous characterization of both the time dependence and spatial characteristics of functional domain motions. Experiments on alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) revealed the presence of internal motion in the NSE coherent form factor arising from the opening dynamics of the cleft between the binding and the catalytic domains that enable binding and release of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) cofactor (45). Also, in a study of DNA polymerase I from Thermus aquaticus (Taq polymerase), NSE results revealed coupled motion between protein domains separated by 7 nm (41).

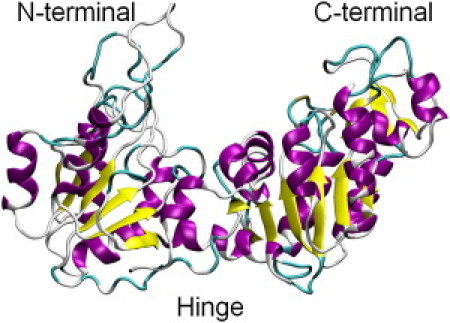

Very recently, NSE measurements on PGK provided what is perhaps the strongest signal yet from internal collective motion (46). PGK is an enzyme involved in the glycolytic pathway that catalyzes the reversible conversion of 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate (1,3-BPG) to 3-phosphoglycerate (3PG) during synthesis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) from adenosine diphosphate (ADP) (31,47–49). PGK has a domain structure with a hinge near the active site between the two domains. As shown in Fig. 1, the binding sites for ATP and 3PG are located in the C-terminal and N-terminal domains, respectively. The NSE experimental results showed evidence of large-scale domain fluctuation dynamics on a timescale of ∼10 ns.

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase (3PGK.pdb).

In the NSE experiments reported to date, investigators interpreted the spectra using simplified normal-mode analyses of the elastic network model (ENM) type (42,44,50,51). ENM models provide approximate descriptions of deformational degrees of freedom in a macromolecule, and in the NSE work reported above, the normal-mode coordinates were shown to provide a reasonably good description of the deformations associated with NSE signals. However, ENM suffers from several disadvantages. It is required to fix the amplitude of the motion by calibration to an experiment. Also, anharmonic motion, which makes up a high proportion of atomic fluctuations at physiological temperatures (15), is neglected. Moreover, ENMs that were developed to best predict temperature factors without regard for the crystal environment yield far too short-ranged atom-atom correlations (50). Low-frequency modes dominate the variance-covariance matrix only for models with a physically reasonable vibrational density of states, and the fraction of modes required for realistic models to converge the correlations is higher than that typically used for ENM studies (50). ENMs also do not explicitly include environmental (solvent) or frictional damping effects. In contrast, although MD simulation is computationally more demanding than ENM, it includes anharmonic and frictional effects from solvent.

Here, we compare results obtained from an MD simulation on yeast PGK and experimental small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) and NSE. The contributions of external and internal motions of the observed spectra are analyzed, and the absolute amplitudes, forms, effective potentials, frictional properties, and time dependence of the dynamics of functional domain motions contributing to the spin-echo spectra are characterized.

Computational details

Details of the MD simulation and the neutron scattering theory are given in the Supporting Material. All scattering calculations were performed with an in-house-developed software called SASSENA (http://cmb.ornl.gov/resources/developments/sassena), which combines principles described in SERENA (52) and SASSIM (53).

Results and Discussion

Small-angle scattering

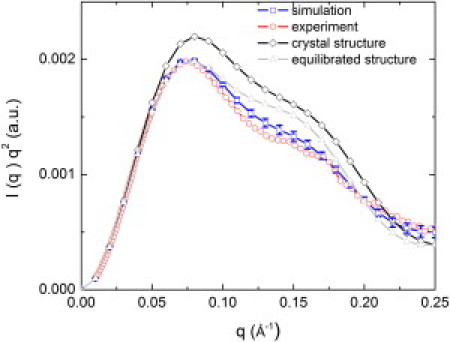

Fig. 2 shows a Kratky plot of the SANS intensity, q2I(q) versus q, calculated from the PGK MD production run and compared with the experimental profile and that calculated from the static crystallographic structure. The experimental and simulation-derived I(q) values are in excellent agreement with each other, and significantly different from the scattering from the crystal structure. This indicates that the structural relaxation in aqueous solution significantly modifies the scattering profile relative to the crystalline state (53,54). The radii of gyration of the crystal structure are 24.3 Å and 23.7 Å from experiment (46), both of which are slightly smaller than that obtained from the simulation (25.2 Å).

Figure 2.

SANS intensity I(q). Squares: From MD simulation (error bars are the standard deviations from the time average). Circles: Experimental data (46). Diamonds: Calculated from crystal structure (3PGK). Gray triangles: Computed from the MD structure obtained after equilibration.

Single-protein spin echo

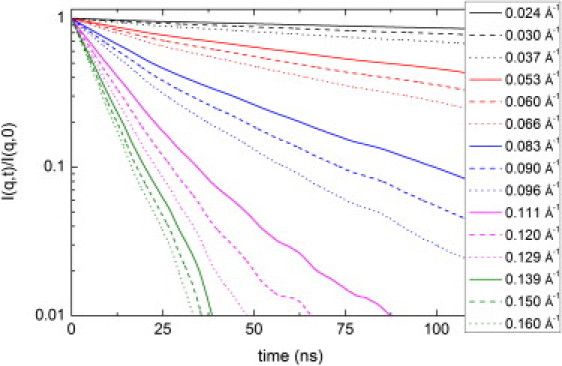

Fig. 3 shows the coherent intermediate scattering function I(q,t)/I(q,0) calculated from the MD simulation at different q-values. The I(q, t)/I(q, 0) spectra can be approximated by a cumulant approximation as (41):

| (1) |

where K2 and K3 are the second and third cumulants, respectively. The effective q-dependent diffusion coefficient Deff can be computed from the initial slope of Г(q) as

| (2) |

Figure 3.

Coherent intermediate scattering function calculated from the MD production run.

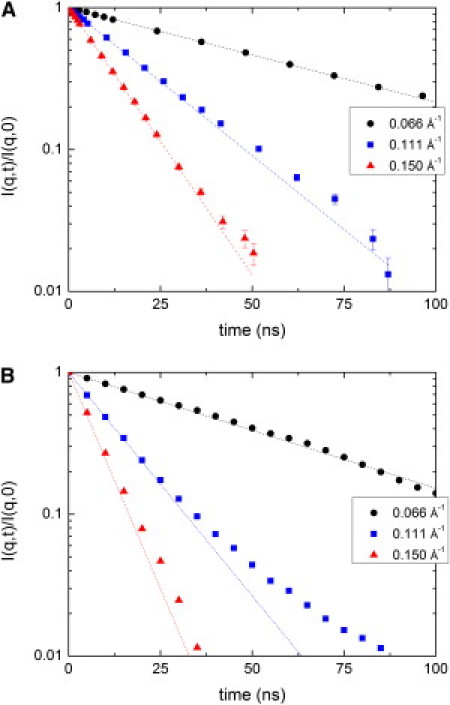

The lnI(q, t)/I(q, 0) spectra at representative q-values are plotted for simulation and experiment in Fig. 4. The dashed lines represent a single-exponential fit over the first 10 ns. Due to the limited length of the simulation (500 ns), the points beyond 50 ns are subject to significant uncertainties.

Figure 4.

Semilogarithmic plot of I(q,t)/I(q, t = 0) for selected q-values. (A) Experimental data for 5% PGK (46). (B) From production MD runs. Dashed lines corresponding to data represent the initial slope extrapolated to long times.

Experimentally, the q-dependent single protein diffusion coefficient at infinite dilution D0(q), i.e, the diffusion coefficient corrected for concentration-dependent interprotein interactions, can be estimated as

| (3) |

where H(q) arises from solvent-mediated hydrodynamic interparticle interactions and the structure factor, S(q), from the direct interprotein interactions (55–57). Here, the assumption is made that D0(q) from the simulation is given by Г(q)/q2, although certain corrections are applied as discussed in detail below.

D0(q) contains contributions from the overall translation and rotation of the protein molecule as well as from internal motions. Assuming decoupling of these motions, D0(q) can be written as

| (4) |

where Dt(q), Dr(q), and Dint(q) are the translational, rotational, and internal coefficients, respectively.

A variety of approaches can be used to estimate the translational, rotational, and internal contributions. Here, we are particularly interested in a comparison between the experimental and simulation-derived internal motion contributions to the NSE. Hence, corrections are applied to the translational and rotational components so as to mimic, when possible, the experimental global-motion profiles as closely as possible.

Translational diffusion

The translational diffusion is q-independent. In MD simulations, periodic boundary conditions and long-range hydrodynamic interactions can introduce an effective coupling between a macromolecule, the solvent, and the periodic images. Therefore, macromolecular diffusion coefficients can significantly depend on the system size. To correct for this, we estimated the translational diffusion coefficient at infinite system size, Dt,inf, by a linear fit of Dt(L) of the PGK molecule to 1/L, which we obtained by performing simulations in different box dimensions, L (Fig. S1).

Furthermore, it is known that the viscosity of TIP3P is underestimated (58,59), and this should, as a consequence, affect the translational diffusion. Therefore, we derived the viscosity of the solvent using the Green-Kubo relation, as described previously (60), from an additional simulation performed of the pure solvent. The resulting value is ηsim = 4.30 × 10−4 kg m−1 s−1 and can be compared with the experimental viscosity of the buffer used in the experimental analysis of ηexp = 16.86 × 10−4 kg m−1 s−1 (46). Hence, we corrected Dt,inf for the viscosity effect using the following equation (59):

| (5) |

The resulting diffusion coefficient is Dt0 = 34.2 ± 2.2 μm2/s and is in reasonable agreement with the single protein translational diffusion coefficient measured by dynamic light scattering of 40.3 ± 0.5 μm2/s (46).

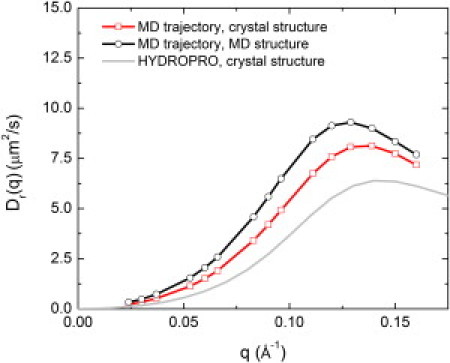

Rotational diffusion

The calculation of rotational diffusion presents considerable challenges. Here, we investigate the rotational NSE calculated with the use of various approximations. The approach taken in the experimental analysis was to calculate the rotational diffusion using the software HYDROPRO, which uses bead-modeling methodologies and the atomic-detail crystal structure (61). The associated Dr(q) is shown in Fig. 5. Also shown in Fig. 5 is Dr(q) derived by also taking the x-ray crystal structure but using the MD trajectory of the rotational motion, obtained by fitting the Cα atoms of the x-ray structure to each MD frame. Finally, Fig. 5 also shows the result of a calculation fitting the Cα atoms of the MD structure obtained after equilibration to each MD frame.

Figure 5.

Rigid-body rotational diffusion NSE Dr(q) of PGK calculated from the MD trajectory using the crystal structure (squares), the MD trajectory and the MD structure obtained after equilibration (circles), and the software HYDROPRO (61) using the crystal structure (gray).

The comparison of Dr(q) calculated using the above three methods shows two significant effects: one arising from the difference in structure between the equilibrated MD geometry and the crystal structure, and one due to the difference in rotational dynamics (i.e., the anisotropy of the rotational diffusion as expressed in the rotational diffusion tensor) between the MD and that assumed by HYDROPRO. Fig. S2 shows how Dr(q) depends systematically on the interdomain distance and the radius of gyration of PGK: the position of the maximum of D(q) shifts approximately linearly to lower q as these quantities increase.

It has been shown that the rotational diffusion coefficients of several proteins calculated in MD simulations using the TIP3P water model are about three times higher than corresponding experimental estimates (62,63). Here, assuming isotropic diffusion motion, we calculated the rotational diffusion coefficient of PGK, Dr, from the MD simulation using the following equation:

| (6) |

where l is the order of the Legendre polynomial, Cl(τ) is the rotational correlation function of the unit vector (defined as the cross product of the vector connecting the center of the hinge and the center of the N-terminal domain and the vector connecting the hinge with the C-terminal domain), and τ is the rotational relaxation time. The l = 2 term was used for consistency with HYDROPRO. No significant system-size dependence of rotational diffusion of the PGK molecules was found, in agreement with a previous study (63). The resulting value of Dr was 8.51 × 10−6 s−1, which is significantly higher than the value of 2.9 × 10−6 s−1 calculated using HYDROPRO, and in agreement with the scaling factors suggested previously (62,63). Hence, we scaled Dr(q) calculated using the crystal structure fitted to the MD trajectory by 8.51/2.9 = 2.93. We used the crystal structure (rather than the average MD structure) here for consistency with the approach taken in the experimental analysis, although this choice is arbitrary.

Internal diffusion coefficient, Dint(q)

To determine the internal diffusion coefficient, we first had to obtain I(q,t)/I(q,0) from the internal dynamics in the MD simulation trajectories. To that end, we obtained the overall translation and rotation of the protein by superimposing the Cα atoms of the trajectory onto the first structure of the production run (Fig. S3 A). We then derived Dint(q) from I(q,t)/I(q,0) using Eq. 2, and the result is shown in Fig. S3 B (black line).

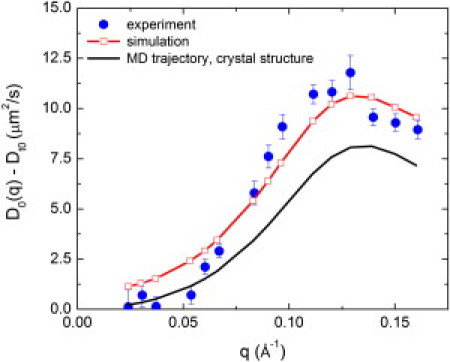

Comparison with experimental NSE

After all corrections are made, the final single-protein diffusion coefficient is represented as

| (7) |

Fig. 6 presents the single protein diffusion coefficient calculated from the total coherent intermediate scattering function using Eqs. 1, 2, and 7. The low q scattering is dominated by the q-independent translational diffusion Dt0, which in Fig. 6 was subtracted from D0(q). The simulation-derived results are in good agreement with the experimental data (46). The maximum of D0(q) is located at the same position (∼0.12 Å−1) as in the experiment, corresponding to the average diameter of PGK (52 Å).

Figure 6.

q dependence of D0(q)-Dt0 for PGK calculated from MD and compared with experimental data for 5% PGK from Inoue et al. (46).

Internal dynamics in detail

To extract the fractional decay in I(q,t)/I(q,0) relative to the rigid-body case A(q), we fitted the internal intermediate scattering function by the following equation: I(q,t)/I(q,0) = (1−A(q))+A(q)exp(−Γintt), where Γint is a rate constant for the exponent. A(q) here is not related to the coherent neutron scattering amplitude defined in Eq. S1. The q dependence of A(q) in Fig. S4 shows that at low q no internal motions contribute, but that with increasing q there is a clear decay due to the internal dynamics, eventually followed by a small plateau. The associated relaxation times 1/Γint reach from 1 ns at low Q up to 8 ns at higher Q. A common relaxation time is ∼6 ns. These results agree qualitatively with the experimentally derived A(q) and Γint, but are roughly an order of magnitude faster and smaller in amplitude.

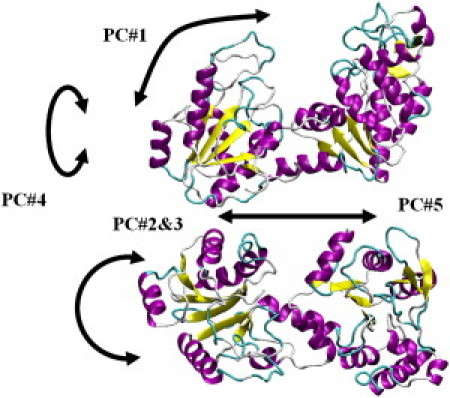

The question arises as to what kind of internal motion leads to the simulation-derived Dint(q). To probe this, we carried out a PCA on the MD trajectory we obtained after removing the global translation and rotation motion. PCA extracts the essential motions sampled by the MD trajectory (15,64,65) (see Section C in the Supporting Material).

Fig. S3 B shows Dint(q) (solid lines) calculated from the trajectories projected onto the PCA eigenvectors. Approximately half of the Dint(q) arises from the first five PCs, which are similar to elastic normal modes 7–9 of Biehl et al. (45). Also, Fig. S3 B shows the contribution from first 10, 50, and 100 components.

Fig. 7 shows schematic cartoons of the five largest-contributing PCs. PC1 is mostly the classic functional hinge bending motion, which opens and closes the catalytic site and thus brings together the ATP and 3PG. The combination of PC2 and PC3 describes the rotational motion of the domains around the axis perpendicular to the image plane. PC4 is the rotation of the domains around the axis connecting them, and, finally, PC5 is the translational motion of the domains relative to each other along the axis in the image plane. Movies depicting motions corresponding to principal components accompany this article (Supporting Material Movie S1, Movie S2, Movie S3, Movie S4, and Movie S5).

Figure 7.

Motional patterns of the first five PCs.

Fig. S5 shows the effective free energy along the first five PC modes. All five modes exhibit broad, flat-bottomed profiles corresponding to approximate quasiharmonic behavior, and the absence of multiminimum dynamics. Finally, as shown in the Supporting Material, we analyzed the dynamics along the principal coordinates by calculating the coordinate autocorrelation function and fitting a probabilistic diffusion-vibration model to the results (66,67). The results are consistent with PCA mode 7 exhibiting highly overdamped diffusional behavior on an effectively flat potential, as seen in the potentials of mean force (68).

Comparison of simulation and experimental amplitudes

The above results indicate a difference between the simulation- and experimentally derived amplitudes of the motions dominating the spin-echo signal. To consider the possible origins of these differences, it is useful to compare the amplitudes with results obtained using other experimental techniques. Here, we compare our results with available fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) measurements for PGK with dyes attached to residues 135 and 290. Table S2 compares these results with FRET and NSE data from the literature. The simulations yield a mean distance between these two residues (<R>) of 46.7 Å, which is higher than the values derived from corresponding FRET and NSE data, and compatible with the higher Rg seen in the simulation. The full width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the distance distribution is 13.0 Å. There is considerable disagreement in the FRET literature FWHM, which varies from 13 to 31.4 Å (69–71). The simulation data presented here are in approximate agreement with the lower values of the FWHM in Table S2, whereas the NSE experimental estimate agrees with the highest value in the table. Analyses of FRET data often employ a number of approximations that have been shown to affect the results, including the ideal dipole approximation (72) and the absence of correlation between orientation and distance (κ and RDA, respectively) between the two fluorescent probes (73,74). In this study, the intrinsic dye mobility and the location in the protein may have a more important effect on the results. Residues 135 and 290 are located on very flexible loops in PGK, the dynamics of which is superposed on the interdomain fluctuations. Hence, the FWHM of this interdomain motion can be several times smaller than the distribution of the distance between the centers of mass of residues 135 and 290.

The dynamic amplitudes extracted from the simulation trajectory are an order of magnitude smaller than that derived from the NSE measurements. On the other hand, there seems to be a good agreement in the effective diffusion derived from the initial slope evaluated. However, in an initial slope the internal motions enter in the form of the product of the amplitude times the relaxation rate. Thus, for a given effective diffusion, a small amplitude A(Q) of the internal motions may be compensated by a faster rate. For example, taking 6 ns (as found in the simulation) versus 60 ns relaxation time would yield 0.02 versus 0.2 in A(Q). A full evaluation of the relaxation curves measured by NSE beyond the initial slope gives the relaxation rate and amplitude separately, yielding the longer relaxation time and also larger amplitude from the experimental data.

This difference in amplitude may be due in part to the determination of the rotational diffusion. In Fig. 5 we demonstrate the dependence of the rotational diffusion on the starting configuration. A too-large rotational diffusion (i.e., a misinterpretation of internal motion as rotational diffusion) will decrease the contribution of the internal dynamics and therefore the amplitude of the internal motions (see Fig. 6). Hence, one must understand the coupling of internal motion to rotational diffusion to determine both from the trajectory.

To estimate the free-energy profile for the hinge bending in PGK, we performed umbrella sampling using as a reaction coordinate, z, the distance between the domains' centers of mass. Fig. S6 shows the potential of mean force (PMF) from umbrella sampling and the corresponding distance distribution from MD simulation. The protein explores a relatively narrow region around z = 38 Å with an amplitude of ∼2 Å, in agreement with the PMF profile.

A simple calculation can be made of the force constant corresponding to the pair distribution function (PDF) given in Fig. S6. Assuming that the PDF is a normal distribution, and that the corresponding effective potential is a quadratic function, we obtain a force constant of K = 0.32 N/m for a mean domain distance of ∼3.8 nm, assuming room temperature. Investigators recently derived an effective force constant of 2.18 N/m assuming a quadratic PMF for the distance of a fluorescein-tyrosine pair 0.45 Å apart within a single protein from fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (75,76). Assuming that PGK protein can be represented by a homogeneous elastic medium, where the restoring force produced by the perturbation of the equilibrium distance between two arbitrary points scales with the reciprocal of the distance, the equilibrium distance in PGK calculated from the ratio of the force constants obtained by Yang et al. (76) would be 3.06 nm. Because the proteins are not the same, this can only be a very rough estimation, but it clearly gives the same order of magnitude.

Independently of the above considerations, many studies have shown that the amplitudes and timescales of motions in MD simulation agree satisfactorily with incoherent neutron scattering experiments that probe the local dynamics of single atoms by measuring the atomic self-correlation. However, coherent scattering in the low-Q regime of SANS and NSE observes the collective motion of complete domains. These larger-amplitude, diffusive interdomain dynamics are qualitatively different and particularly sensitive to hydrodynamic and other environmental effects in the simulation (77). Experimentally, cooperative motions have been found to be strongly dependent on the exact environment, such as the salt concentration pH or solvent (69) (J. Fitter, Institut für Strukturbiologie und Biophysik (ISB-2), Forschungszentrum Jülich, personal communication, 2011). For PGK, recent studies (78) suggested that a hydrophobic patch at the back side of the cleft is essential for the opening motions, and the effective salt concentration, pH, and hydrophobicity will alter the effective potential found for the PCs as an effective long-range potential for cooperative motions.

Conclusions

Some comment is useful to clarify the relationship between ENMs and MD in the context of NSE. ENM is clearly very useful for estimating global protein dynamics with broad brush strokes. However, MD simulation with an atomistic molecular-mechanics potential function in explicit solvent has the potential to provide a more detailed and accurate description of the dynamics associated with NSE than does ENM, as well as to characterize the underlying physics of the coupled rotational, translational, and internal motions involved.

Although MD simulation is computationally more demanding than ENM, it includes anharmonic and solvation effects from first principles. As a result, we can draw several relevant conclusions from our MD analysis that cannot be made from ENM. We were able to modify the SANS profile in aqueous solution relative to the crystalline state. Furthermore, the MD simulation allowed us to explore the translational and rotational dynamics. We derived the effective free energy along the PC modes concerned, and the MD enabled us to analyze the dynamics along the principal coordinates by calculating the coordinate autocorrelation function and fitting a probabilistic diffusion-vibration model to the results. The results are consistent with the modes involved exhibiting highly overdamped diffusional behavior on an effectively flat potential.

The interpretation of NSE presents a fascinating challenge, and this work represents what is to our knowledge the first attempt to use MD for that purpose. An MD comparison may not yield spectra in as good accord as those obtained by fitting simplified ENM modes, largely because, in contrast to ENM, the MD amplitudes and timescales cannot be adjusted to fit the experimental results. Moreover, the MD comparison identified interesting physical problems that need to be addressed in future work. Translational diffusion is relatively easy to account for, and provides a q-independent background to D0(q). However, the rotational and internal dynamics are more difficult to disentangle. The flexibility and anisotropy of biological macromolecules leads to the rotational and internal motions being, in principle, coupled, and it will be interesting to characterize the nature of this coupling in detail in the future. Assuming decoupling, the anisotropic rotational diffusion tensor and corresponding rotating molecular shape must be evaluated. Our results suggest that this determination is nontrivial. In contrast to MD simulations, in neutron-scattering measurements in solution the internal dynamics is not directly accessible. However, in MD simulations, the hydrodynamics is not well described by the TIP3P water and is also influenced by the box size. Properties such as solvent viscosity clearly play a major role, and here we used perceived deficiencies in the model solvent viscosity to quantitatively correct the calculated global rotational dynamics. In principle, the internal part of D(q) may also need to be rescaled, but it is difficult to determine the scaling factor for this because there are contributions from both viscosity-dependent domain-water and viscosity-independent domain-domain interactions. A challenge for the future will be to develop simulation methodologies and potentials that accurately reproduce NSE results without the need for corrections (such as were applied in this work) to allow a better description of the internal dynamics. Furthermore, it would be interesting to examine the coupling between the translational, rotational, and internal motions in the simulation. It is hoped that MD will eventually enable investigators to unravel the complex physics underlying NSE, and that simplified models of the dynamics, such as ENM, will be developed and refined from the MD results. Hence, MD may represent a stepping-stone between experiment and improved ENM models of NSE dynamics.

The results of our MD analysis indicate that large-amplitude, highly overdamped internal domain motions involving diffusional behavior on an effectively flat potential contribute significantly to NSE signals. Our MD/NSE analysis allowed us to describe the contributing atoms, the effective dynamic PMF, and the dynamics on the potential, i.e., the time dependence as determined by the effective friction. Continuing improvements in the accuracy of macromolecular simulations and in the development of NSE instruments (e.g., as is under way at the Oak Ridge Spallation Neutron Source) hold promise for the future.

Acknowledgments

The research was sponsored by the Laboratory Directed Research and Development Program of Oak Ridge National Laboratory, managed by UT-Battelle, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy under contract No. DE-AC05-00OR22725. This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, which is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Smith J., Cusack S., Karplus M. Inelastic neutron-scattering analysis of low-frequency motion in proteins—a normal mode study of the bovine pancreatic trypsin-inhibitor. J. Chem. Phys. 1986;85:3636–3654. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith J.C. Protein dynamics: comparison of simulations with inelastic neutron scattering experiments. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1991;24:227–291. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500003723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaccai G. How soft is a protein? A protein dynamics force constant measured by neutron scattering. Science. 2000;288:1604–1607. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5471.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabel F., Bicout D., Zaccai G. Protein dynamics studied by neutron scattering. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2002;35:327–367. doi: 10.1017/s0033583502003840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cusack S., Smith J., Karplus M. Inelastic neutron scattering analysis of picosecond internal protein dynamics. Comparison of harmonic theory with experiment. J. Mol. Biol. 1988;202:903–908. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90566-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamy A.V., Smith J.C., Kataoka M. High-resolution vibrational inelastic neutron scattering: a new spectroscopic tool for globular proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:9268–9273. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balog E., Becker T., Smith J.C. Direct determination of vibrational density of states change on ligand binding to a protein. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004;93:028103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.028103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moritsugu K., Njunda B.M., Smith J.C. Theory and normal-mode analysis of change in protein vibrational dynamics on ligand binding. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:1479–1485. doi: 10.1021/jp909677p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balog E., Perahia D., Merzel F. Vibrational softening of a protein on ligand binding. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:6811–6817. doi: 10.1021/jp108493g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doster W., Cusack S., Petry W. Dynamical transition of myoglobin revealed by inelastic neutron scattering. Nature. 1989;337:754–756. doi: 10.1038/337754a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith J., Kuczera K., Karplus M. Dynamics of myoglobin: comparison of simulation results with neutron scattering spectra. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:1601–1605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daniel R.M., Dunn R.V., Smith J.C. The role of dynamics in enzyme activity. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2003;32:69–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.142445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayward J.A., Smith J.C. Temperature dependence of protein dynamics: computer simulation analysis of neutron scattering properties. Biophys. J. 2002;82:1216–1225. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75478-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayward J.A., Finney J.L., Smith J.C. Molecular dynamics decomposition of temperature-dependent elastic neutron scattering by a protein solution. Biophys. J. 2003;85:679–685. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74511-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tournier A.L., Smith J.C. Principal components of the protein dynamical transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003;91:208106. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.208106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Becker T., Smith J.C. Energy resolution and dynamical heterogeneity effects on elastic incoherent neutron scattering from molecular systems. Phys. Rev. E. 2003;67:021904. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.67.021904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis J.E., Tarek M., Tobias D.J. Methyl group dynamics as a probe of the protein dynamical transition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:15928–15929. doi: 10.1021/ja0480623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarek M., Tobias D.J. Single-particle and collective dynamics of protein hydration water: a molecular dynamics study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;89:275501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.275501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarek M., Tobias D.J. Role of protein-water hydrogen bond dynamics in the protein dynamical transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;88:138101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.138101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarek M., Tobias D.J. The dynamics of protein hydration water: a quantitative comparison of molecular dynamics simulations and neutron-scattering experiments. Biophys. J. 2000;79:3244–3257. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76557-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tournier A.L., Xu J.C., Smith J.C. Translational hydration water dynamics drives the protein glass transition. Biophys. J. 2003;85:1871–1875. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74614-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kneller G.R., Hinsen K. Fractional Brownian dynamics in proteins. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;121:10278–10283. doi: 10.1063/1.1806134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood K., Grudinin S., Zaccai G. Dynamical heterogeneity of specific amino acids in bacteriorhodopsin. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;380:581–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kneller G.R., Calandrini V. Self-similar dynamics of proteins under hydrostatic pressure-Computer simulations and experiments. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1804:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kneller G.R., Smith J.C. Liquid-like side-chain dynamics in myoglobin. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;242:181–185. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dellerue S., Petrescu A.J., Bellissent-Funel M.C. Radially softening diffusive motions in a globular protein. Biophys. J. 2001;81:1666–1676. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75820-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neusius T., Daidone I., Smith J.C. Subdiffusion in peptides originates from the fractal-like structure of configuration space. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100:188103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.188103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCammon J.A., Gelin B.R., Wolynes P.G. The hinge-bending mode in lysozyme. Nature. 1976;262:325–326. doi: 10.1038/262325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmai Z., Chaloin L., Balog E. Substrate binding modifies the hinge bending characteristics of human 3-phosphoglycerate kinase: a molecular dynamics study. Proteins. 2009;77:319–329. doi: 10.1002/prot.22437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varga A., Szabó J., Vas M. Thermodynamic analysis of substrate induced domain closure of 3-phosphoglycerate kinase. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3660–3664. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banks R.D., Blake C.C.F., Phillips A.W. Sequence, structure and activity of phosphoglycerate kinase: a possible hinge-bending enzyme. Nature. 1979;279:773–777. doi: 10.1038/279773a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qi G.Y., Hayward S. Database of ligand-induced domain movements in enzymes. BMC Struct. Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-9-13. 2009;9:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faure P., Micu A., Benoit J.P. Correlated intramolecular motions and diffuse X-ray scattering in lysozyme. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1994;1:124–128. doi: 10.1038/nsb0294-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Héry S., Genest D., Smith J.C. X-ray diffuse scattering and rigid-body motion in crystalline lysozyme probed by molecular dynamics simulation. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;279:303–319. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meinhold L., Smith J.C. Correlated dynamics determining x-ray diffuse scattering from a crystalline protein revealed by molecular dynamics simulation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;95:218103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.218103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meinhold L., Merzel F., Smith J.C. Lattice dynamics of a protein crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007;99:138101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.138101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keppler C., Achterhold K., Parak F. Determination of the phonon spectrum of iron in myoglobin using inelastic X-ray scattering of synchrotron radiation. Eur. Biophys. J. 1997;25:221–224. doi: 10.1007/s002490050034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu D., Chu X.Q., Chen S.H. Studies of phononlike low-energy excitations of protein molecules by inelastic x-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;101:135501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.135501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dellerue S., Petrescu A., Bellissent-Funel M.C. Collective dynamics of a photosynthetic protein probed by neutron spin-echo spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulation. Physica B. 2000;276:514–515. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bellissent-Funel M.C., Daniel R., Smith J.C. Nanosecond protein dynamics: first detection of a neutron incoherent spin-echo signal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:7347–7348. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bu Z.M., Biehl R., Callaway D.J. Coupled protein domain motion in Taq polymerase revealed by neutron spin-echo spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:17646–17651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503388102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farago B., Li J.Q., Bu Z. Activation of nanoscale allosteric protein domain motion revealed by neutron spin echo spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2010;99:3473–3482. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.09.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Biehl R., Monkenbusch M., Richter D. Exploring internal protein dynamics by neutron spin echo spectroscopy. Soft Matter. 2011;7:1299–1307. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bu Z., Callaway D.J.E. Proteins move! Protein dynamics and long-range allostery in cell signaling. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2011;83:163–221. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381262-9.00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biehl R., Hoffmann B., Richter D. Direct observation of correlated interdomain motion in alcohol dehydrogenase. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;101:138102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.138102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Inoue R., Biehl R., Richter D. Large domain fluctuations on 50-ns timescale enable catalytic activity in phosphoglycerate kinase. Biophys. J. 2010;99:2309–2317. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harlos K., Vas M., Blake C.F. Crystal structure of the binary complex of pig muscle phosphoglycerate kinase and its substrate 3-phospho-D-glycerate. Proteins. 1992;12:133–144. doi: 10.1002/prot.340120207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watson H.C., Walker N.P.C., Shaw P.J., Bryant T.N., Wendell P.L., Fothergill L.A., Perkins R.E., Conroy S.C., Dobson M.J., Tuite M.F. Sequence and structure of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase. EMBO J. 1982;1:1635–1640. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davies G.J., Gamblin S.J., Watson H.C. The structure of a thermally stable 3-phosphoglycerate kinase and a comparison with its mesophilic equivalent. Proteins. 1993;15:283–289. doi: 10.1002/prot.340150306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riccardi D., Cui Q., Phillips G.N., Jr. Evaluating elastic network models of crystalline biological molecules with temperature factors, correlated motions, and diffuse x-ray scattering. Biophys. J. 2010;99:2616–2625. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riccardi D., Cui Q., Phillips G.N., Jr. Application of elastic network models to proteins in the crystalline state. Biophys. J. 2009;96:464–475. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Micu A.M., Smith J.C. Serena—a program for calculating x-ray diffuse-scattering intensities from molecular-dynamics trajectories. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995;91:331–338. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Merzel F., Smith J.C. SASSIM: a method for calculating small-angle X-ray and neutron scattering and the associated molecular envelope from explicit-atom models of solvated proteins. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:242–249. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901019576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Svergun D.I., Richard S., Zaccai G. Protein hydration in solution: experimental observation by x-ray and neutron scattering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:2267–2272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pusey P.N. Dynamics of interacting Brownian particles. J. Phys. Math. Gen. 1975;8:1433–1440. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ackerson B.J. Correlations for interacting Brownian particles. J. Chem. Phys. 1976;64:242–246. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Banchio A.J., Nägele G. Short-time transport properties in dense suspensions: from neutral to charge-stabilized colloidal spheres. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;128:104903. doi: 10.1063/1.2868773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yeh I.C., Hummer G. System-size dependence of diffusion coefficients and viscosities from molecular dynamics simulations with periodic boundary conditions. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:15873–15879. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yeh I.C., Hummer G. Diffusion and electrophoretic mobility of single-stranded RNA from molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 2004;86:681–689. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74147-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Palmer B.J. Transverse-current autocorrelation-function calculations of the shear viscosity for molecular liquids. Phys. Rev. E. 1994;49:359–366. doi: 10.1103/physreve.49.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.García De La Torre J., Huertas M.L., Carrasco B. Calculation of hydrodynamic properties of globular proteins from their atomic-level structure. Biophys. J. 2000;78:719–730. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76630-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wong V., Case D.A. Evaluating rotational diffusion from protein MD simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:6013–6024. doi: 10.1021/jp0761564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takemura K., Kitao A. Effects of water model and simulation box size on protein diffusional motions. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:11870–11872. doi: 10.1021/jp0756247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karplus M., Kushick J.N. Method for estimating the configurational entropy of macromolecules. Macromolecules. 1981;14:325–332. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kitao A., Hayward S., Go N. Energy landscape of a native protein: jumping-among-minima model. Proteins. 1998;33:496–517. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19981201)33:4<496::aid-prot4>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moritsugu K., Smith J.C. Temperature-dependent protein dynamics: a simulation-based probabilistic diffusion-vibration Langevin description. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:5807–5816. doi: 10.1021/jp055314t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moritsugu K., Smith J.C. Langevin model of the temperature and hydration dependence of protein vibrational dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:12182–12194. doi: 10.1021/jp044272q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hess B. Convergence of sampling in protein simulations. Phys. Rev. E. 2002;65:031910. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.65.031910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rosenkranz T., Schlesinger R., Fitter J. Native and unfolded states of phosphoglycerate kinase studied by single-molecule FRET. ChemPhysChem. 2011;12:704–710. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201000701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lillo M.P., Beechem J.M., Mas M.T. Design and characterization of a multisite fluorescence energy-transfer system for protein folding studies: a steady-state and time-resolved study of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11261–11272. doi: 10.1021/bi9707887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Haran G., Haas E., Mas M.T. Domain motions in phosphoglycerate kinase: determination of interdomain distance distributions by site-specific labeling and time-resolved fluorescence energy transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:11764–11768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Muñoz-Losa A., Curutchet C., Mennucci B. Fretting about FRET: failure of the ideal dipole approximation. Biophys. J. 2009;96:4779–4788. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.VanBeek D.B., Zwier M.C., Krueger B.P. Fretting about FRET: correlation between κ and R. Biophys. J. 2007;92:4168–4178. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.092650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hoefling M., Lima N., Grubmüller H. Structural heterogeneity and quantitative FRET efficiency distributions of polyprolines through a hybrid atomistic simulation and Monte Carlo approach. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Min W., Luo G.B., Xie X.S. Observation of a power-law memory kernel for fluctuations within a single protein molecule. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;94:198302. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.198302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang H., Luo G.B., Xie X.S. Protein conformational dynamics probed by single-molecule electron transfer. Science. 2003;302:262–266. doi: 10.1126/science.1086911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lange O.F., van der Spoel D., de Groot B.L. Scrutinizing molecular mechanics force fields on the submicrosecond timescale with NMR data. Biophys. J. 2010;99:647–655. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zerrad L., Merli A., Bowler M.W. A spring-loaded release mechanism regulates domain movement and catalysis in phosphoglycerate kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:14040–14048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.206813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hess B., Kutzner C., Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brooks B.R., Bruccoleri R.E., Karplus M. Charmm—a program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 1983;4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jorgensen W.L., Chandrasekhar J., Klein M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald—an N.Log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Essmann U., Perera L., Pedersen L.G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Berendsen H.J.C., Postma J.P.M., Haak J.R. Molecular-dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hoover W.G. Canonical dynamics: equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys. Rev. A. 1985;31:1695–1697. doi: 10.1103/physreva.31.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nose S. A molecular-dynamics method for simulations in the canonical ensemble. Mol. Phys. 1984;52:255–268. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nose S., Klein M.L. Constant pressure molecular-dynamics for molecular systems. Mol. Phys. 1983;50:1055–1076. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Parrinello M., Rahman A. Polymorphic transitions in single-crystals—a new molecular-dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981;52:7182–7190. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.