Abstract

The aggregation of proteins or peptides into amyloid fibrils is a hallmark of protein misfolding diseases (e.g., Alzheimer's disease) and is under intense investigation. Many of the experiments performed are in vitro in nature and the samples under study are ordinarily exposed to diverse interfaces, e.g., the container wall and air. This naturally raises the question of how important interfacial effects are to amyloidogenesis. Indeed, it has already been recognized that many amyloid-forming peptides are surface-active. Moreover, it has recently been demonstrated that the presence of a hydrophobic interface can promote amyloid fibrillization, although the underlying mechanism is still unclear. Here, we combine theory, surface property measurements, and amyloid fibrillogenesis assays on islet amyloid polypeptide and amyloid-β peptide to demonstrate why, at experimentally relevant concentrations, the surface activity of the amyloid-forming peptides leads to enriched fibrillization at an air-water interface. Our findings indicate that the key that links these two seemingly different phenomena is the surface-active nature of the amyloid-forming species, which renders the surface concentration much higher than the corresponding critical fibrillar concentration. This subsequently leads to a substantial increase in fibrillization.

Introduction

Several protein-misfolding diseases, such as type II diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer's disease, share a common pathological mechanism in which aggregation of proteins or peptides leads to the formation and deposition of amyloid fibrils (1). Amyloidogenesis occurs via a nucleation-dependent polymerization process during which there is an energetically unfavorable assembly of monomers into nuclei (lag phase), and then the nuclei elongate to reach a final fibrillar concentration that is at a dynamic equilibrium with the residual monomer concentration (2). Given its intimate relationship to human pathology, amyloidogenesis is currently under intense investigation. Despite having different amino-acid sequences, and originating from different cellular locations and proteolytic cleavage(s) of different proteins, amyloid-forming peptides share a common structure once assembled (crossβ-sheet fold) and physico-chemical properties, such as amphiphilicity (1). This amphiphilic character confers surfactant properties on islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP, involved in type II diabetes mellitus), amyloid-β peptide (Aβ, involved in Alzheimer's disease), and an amyloid-forming peptide from human acetylcholinesterase (3–5). This can be seen from the fact that, in the presence of an air-water interface (AWI; nonpolar gas and polar aqueous solution), the surface tension of a sample can be significantly reduced when these peptides are added, which implies that amyloid peptides adsorb at the AWI. Protein or peptide adsorption is a complex process, which involves interface adsorption and changes in secondary structure, and results in interfacial multilayer formation (6,7). Adsorption of proteins occurs at hydrophobic-hydrophilic interfaces, such as gas-liquid or solid-liquid (6,8). Protein adsorption also has significant implication in the activity of proteins toward membranes, with amphiphilic proteins binding to membrane interfaces (9,10). This property has been used by a variety of membrane-active peptides to form transmembrane pores, to destabilize or to solubilize membranes (9).

Outside of the well-known bacterial pore-forming peptides, amyloid peptides or proteins also exploit their amphiphilicity to bind to membranes and to use membranes to facilitate their assembly into amyloid fibrils (5,11). Amyloid peptides exploit adsorption at hydrophobic-hydrophilic interfaces during their assembly into fibrils to promote peptide chains alignment in which polar and nonpolar side chains segregate on opposite sides of the β-strand and orientate toward the hydrophilic and hydrophobic phases, respectively (3,5,11). However, most previous studies on amyloid formation have neglected the surfactant activities of these peptides and have used in vitro systems without recognizing the importance of interfacial adsorption in the process of amyloid assembly. It is therefore paramount to identify the effects induced by the presence of nonphysiological interfaces, such as the container wall and air. For instance, it has been recently discovered that the presence of a hydrophobic interface, or an AWI, can substantially promote assembly into amyloid fibrils (12–16). An understanding of such an underlying mechanism is still incomplete.

Superficially, the surface activity of amyloidogenic peptides and the fact that the AWI promotes amyloidogenesis seem to be connected, although the actual mechanism that links these two observations is unknown. Here, we propose a simple explanation that connects these two phenomena. Specifically, we argue that the surface activity of amyloid-forming peptides renders them highly concentrated at the AWI. Because the amount of peptides above the critical fibrillar concentration (an intrinsic quantity associated to any amyloidogenic systems) will all be converted into fibrils, the presence of the AWI therefore promotes fibrillization by spatially concentrating the amount of peptides.

Materials and Methods

Synthetic peptides

Human IAPP (Bachem, Weil am Rhein, Germany) and Aβ1-40 (EZBiolab, Carmel, IN) were resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (stock solution at 1.6 mM for Aβ1-40 and 512.4 μM for IAPP). DMSO is widely used for preparation of stock solutions of amyloid peptides because it maintains these peptides in a monomeric pool lacking any β-sheet secondary structures (17,18). To further ensure that our preparations are as free as possible of any preaggregated species, we sonicated and centrifuged (1 h at 15,000 × g at + 4°C) the DMSO stock solutions before use. Both sonication and centrifugation are commonly used in the preparation of disaggregated amyloid solutions (18,19). The solution of both IAPP and Aβ was free from seeds or other amyloidogenic material, as judged by the reproducible aggregation behavior of both peptides.

Fibrillization experiments

Several concentrations of IAPP were dispensed in a 96-well plate (Microclear, polystyrene, black wall, clear bottom; Greiner Bio-One, Stonehouse, Gloucestershire, UK) with 32 μM thioflavin T (ThT) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), in a 100 μL final solution volume. The 32 μM ThT used in our amyloidogenesis assays was previously used successfully to study IAPP fibrillization and is also comprised within the ThT concentration range used to monitor amyloid kinetics (e.g., up to 50 μM ThT) (20,21). In a different amyloid system (insulin), increasing ThT concentrations (up to 80 μM) resulted in analogous fibrillization kinetics (22). ThT fluorescence (excitation 450 nm, emission 480 nm) was measured at 37°C on a BMG Polarstar plate reader (BMG Labtech, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, UK) using a bottom-bottom configuration (optical fiber system detecting emission signal from the bottom of the well).

For 10 μM IAPP, the reaction was performed in the absence or presence of Perspex cylinders introduced at the start of the reaction. The cylinders are cylindrical rods with a hemispherical tip, manufactured in house from an 8-mm Perspex sheet (polymethyl methacrylate; Alternative Plastics, Nuneaton, Warwickshire, UK), their dimensions are 6.6 mm in diameter and 6 mm in height. The introduction of the cylinders into the wells removed the AWI (hydrophobic gas and hydrophilic aqueous solution) and created a new interface, a Perspex-solution interface (12). Due to the hydrophilicity of Perspex, the new Perspex-solution interface is a hydrophilic-hydrophilic interface rather than a hydrophobic-hydrophilic one. The hemispherical tip of the cylinder prevented the formation of air bubbles beneath the cylinder. Control wells contained buffers (without peptide) and Perspex cylinders when required. The values of control wells (buffer with or without cylinder) were subtracted from the values of test wells (peptide with or without cylinder). After each experiment, the cylinders were cleaned by immersion in 3 M NaOH solution for a minimum of 3–4 h, rinsed with distilled water, then air-dried out of EtOH, and manipulated with gloves. At least three independent assays were performed and analyzed with the two-sample t-test.

Surface activity measurement

DMSO stock solutions of IAPP or Aβ1-40 were diluted in 160 μL 200 mM sodium acetate pH 3, 40 μL 1 M NaH2PO4 pH 7, or an IAPP 32 μM ThT reaction at plateau, and dispensed in a 96-well plate (black wall, clear bottom; Greiner Bio-One). Surface activity was measured repeatedly at 1 min intervals, at 520 nm on a BMG Polarstar plate reader at the central and offset positions, as previously described (4) (see also Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material). After 1 h measurement, the plate was taken out of the plate reader and allowed to rest ∼10 min before the bottom-half (100 μL) of the 200 μL reaction was removed with a 30-gauge needle. The needle was positioned vertically to the reaction surface and inserted such that the tip of the needle was touching the bottom of the well. The thinness of the 30-gauge needle allowed minimal disturbance of the surface of the reaction. The bottom-half of the solution was drawn very slowly (3–4 μL/s by hand) such that no visible flow in the well was detected. We can confidently assume that no significant disturbance of the interface took place during the partitioning because no surface activity or surface tension was detected for the bulk fractions of 0.6 μM IAPP or Aβ when the corresponding surface fractions were highly surface-active (see results section “Amyloid precursors strongly adsorb at the AWI and are depleted from the bulk solution in a concentration dependent manner”). The removed bottom-half of the reaction (bulk fraction) was placed in a new well and the undisturbed top-half (surface fraction) remained in the original well. Surface activity of the top and bottom halves was measured at the central and offset positions. For the surface activity measurement of fibrillar IAPP, several concentrations of IAPP were incubated with 32 μM ThT in PBS and changes in ThT fluorescence were monitored until the reaction reached plateau. Then the surface activity and ThT fluorescence of fully fibrillized IAPP was measured before and after partitioning of the bulk fraction from the surface. ΔOD = (ODoffset position – ODcentral position). At least three independent assays were performed and analyzed with the two-sample t-test.

Surface tension measurement

DMSO stock solutions of IAPP were diluted in PBS to 0.6 and 4 μM. The solution was aspirated manually into an Attension precision manual syringe with steel needles (Biolin Scientific, Coventry, West Midlands, UK). Surface tension was measured by pendant drop-shape analysis using the Attension Theta optical tensiometer with the software OneAttension v1.03 (Biolin Scientific). The calculations were performed using the Young-Laplace curve-fitting method.

Calculations of the critical concentrations used in the modeling

Setting the unit of volume to the volume of a peptide monomer in the fibrillar form, one can equate the critical fibrillar concentration to such that

and ΔH is the binding enthalpy at the end of an amyloid fibril, ν corresponds to the roaming volume of each monomer within the fibril (entropic contribution from spatial degrees of freedom), and θ corresponds to the roaming area on a unit sphere for the director of each monomer (entropic contribution from rotational degrees of freedom) (23). Specifically, if the volume fraction of protein in solution is beyond , then fibrils will form and the final monomer volume fraction in the system will be . Note that in the case of the hen lysozyme and Aβ1-40 fibrils, ξ has been estimated to be ∼−10 kcal/mol (23,24). Here, we will assume that the structures of the fibrils at the surface and in the bulk are similar. In other words, both the enthalpic and entropic contributions in ξ for the surface and bulk fibrillar species are similar and as a result, the critical fibrillar concentration (CFC) at the surface is the same as the CFC in the bulk, , i.e., ≈ .

Results and Discussion

The final amount of amyloid fibrils is dictated by the presence of an AWI

In vitro experiments are prevalent in the study of amyloidosis. Here, we focus specifically on the presence of the AWI and its effect on the outcome of amyloid fibrillization. The AWI represents a very attractive model for a hydrophobic interface (nonpolar gas) due to its homogeneity, molecular smoothness, and reproducibility, and is the hydrophobic interface that is almost always present during in vitro experiments. Experimentally, we followed the kinetics of IAPP aggregation in the presence and absence of an AWI, using staining with a typical amyloid dye (ThT). The AWI was removed by introducing hydrophilic Perspex cylinders with a hemispherical tip into both control and test wells, as previously described (12). Perspex is very hydrophilic, water interacts more strongly with Perspex than surfactants do, and the concentration of surfactants at Perspex-solution interface is lower than at the AWI to the extent that surfactants cannot form a multilayer at Perspex-solution interfaces (25). Therefore, the new Perspex-solution interface created replaced the hydrophobic-hydrophilic interface (nonpolar gas-polar aqueous solution; AWI) by a hydrophilic-hydrophilic interface (hydrophilic Perspex-solution). Amyloid peptides, such as IAPP, are surface-active and therefore trigger meniscus curvature by lowering the surface tension of a solution (5). The hemispherical tip of the cylinder compensates for such meniscus curvature and prevents the trapping of air bubbles beneath the cylinder upon insertion into the well.

The removal of the AWI at the start of a 10 μM IAPP reaction allowed fibrillogenesis but resulted in a significant 2.5-fold decrease in IAPP plateau height (Fig. 1). Thus, we found that the final amount of amyloid fibrils at equilibrium, as measured by the intensity of ThT fluorescence, can be substantially different depending on whether the AWI is present.

Figure 1.

Height of IAPP plateau depends on the presence of the AWI. A quantity of 10 μM IAPP was incubated with 32 μM ThT with or without AWI removal at the start of the reaction. ThT fluorescence changes were monitored with the plateau heights depicted (inset). The term a.u. is “arbitrary units”. The mean of at least three independent assays is shown. Error bars represent mean ± SE.

Linking surface activity with enriched amyloidogenesis (theory)

We then examined theoretically the connection between amyloidogenic peptide surface activity and the increased amyloidogenesis in the presence of a hydrophobic interface, as observed in Fig. 1. The study of thermodynamic of self-assembly is a well-established subject and has been well verified in different experimental systems (26). We consider a peptide solution in a cubic volume of length L. The corresponding AWI thus has area L2 (see Fig. S2). We assume the total number of amyloid-forming molecules in the system to be N, and we consider four different species in this system: bulk monomers, surface monomers, bulk monomers in fibrillar form, and surface monomers in fibrillar form. We denote the corresponding number of molecules constituting these four species by mb, ms, fb, and fs, respectively. By the conservation of molecules, we have N = mb + ms + fb + fs. We then denote the number of molecules adsorbed at the AWI by Γ, which is a function of mb, ms, fb, and fs, and also the area of the meniscus. We now partition the whole system into two parts—the surface adsorbed layer of depth η, and the bulk component. Note that we have assumed that two components are sharply separated, i.e., the composition changes rapidly from the surface-adsorbed layer to the bulk solution. This is a reasonable assumption, given that the change over width is usually of the scale of the molecular size (27). In both components, the standard analysis on aggregation phenomena applies and so one would expect that for each component, there is a specific CFC beyond which all additional monomers in the system would be in the fibrillar form (26,28). We denote the CFC for the surface component by , then fs is only nonzero if Γ/(ηL2) > . Similarly, fb is nonzero only if (N − Γ)/L2(L − η) > , where is the CFC for the bulk component. We could then consider two different scenarios captured by this simple theoretical model:

-

1.

The first scenario is that surface adsorption is negligible compared to the bulk concentration, i.e., Γ ≪ N. This may correspond to weak adsorption or to highly concentrated solutions such that Γ is saturated at a value much less than N due to the complete filling of the AWI.

-

2.

The second scenario is that surface adsorption is so strong that the overall concentration in the bulk component drops below . In other words, fibrils only form in the surface component.

In the first scenario, the total amount of fibril ftot in the system is

where, in the last approximation, we have assumed that L ≫ η and ≈ (please see Materials and Methods).

For the second scenario, where the adsorption is so strong that the volume fraction in the bulk is less than , we have

In the case of very strong adsorption and low concentration, we may have the surface-adsorbed amount being comparable to the total amount of molecules in the system, i.e., Γ ≈ N. Furthermore, because we have argued that L ≫ η and ≈ , we expect that generally ηL2 ≪ L3. These two observations combined indicate that the total amount of fibrils in the second case, when surface adsorption is strong, would be much greater than in the first scenario, when surface adsorption is negligible compared to the bulk concentration. This explains the experimental results in Fig. 1, in which the presence of an AWI significantly increased IAPP plateau height (2.5-fold). Therefore, our data suggest that the model with strong surface adsorption best explains experimental observations and predicts that the majority of precursors and assembled fibrils should be partitioned into a surface layer.

Amyloid precursors strongly adsorb at the AWI and are depleted from the bulk solution in a concentration-dependent manner

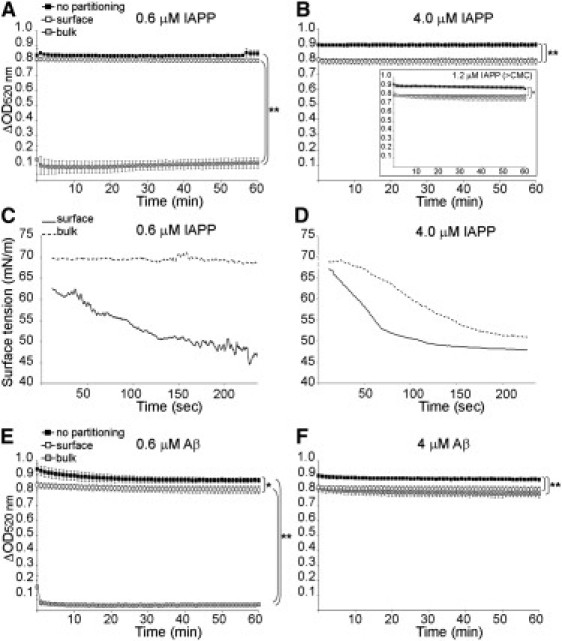

The above theoretical analysis indicated that the amount of fibrils in the system depends strongly on the adsorption strength of amyloid-forming peptides. To verify the adsorption strength of amyloid species either as a whole system or as a bulk and surface fractions, we qualitatively measured the dynamics of surface activity of IAPP and Aβ precursor species at various concentrations (Fig. 2, A–F). We made use of a previously described technique based on an off-axial light beam to measure the lensing effect of a meniscus (see Fig. S1) (4). Normalizing the apparent optical density measured at the offset using the optical density measured on the central axis (ΔOD) gives a value strongly inversely correlated with surface tension (R > 0.97) (4).

Figure 2.

Amyloid assembly requires recruitment and adsorption of monomers at the AWI. Dynamic measurement of the surface activity for a whole reaction (nonpartitioned) and for the bulk and surface fractions of IAPP at 0.6 (A), 1.2 (inset in B), and 4 μM (B). The surface tension for the bulk and surface fractions of IAPP at 0.6 (C) and 4 μM (D) was also monitored over time (the graphs show 18-point moving averages of the raw data). Dynamic measurement of the surface activity for a whole reaction and for the bulk and surface fractions of Aβ1-40 at 0.6 (E) and 4 μM (F). ΔOD calculations were as described in Materials and Methods. a.u.: arbitrary units. The mean of at least three independent assays is shown. Error bars represent mean ± SE. Asterisk indicates p < 0.05 and double-asterisk indicates p < 0.02 for all time points of the time course.

First, dynamic measurements were taken at the start of the fibrillization reaction, which allowed the assessment of the surfactant activity of amyloid precursors in the entire system (referred to as no partitioning in Fig. 2).

Second, we used a novel (to our knowledge) physical repartitioning technique to split the whole reaction, during which the bulk fraction was drawn very slowly and placed in a new well and the undisturbed surface fraction remained in the original well. Then the dynamic surfactant activity of both fractions was measured.

After partitioning, the surface region was considered to be the AWI but also the portion of the system that separates the bulk solution from the adsorbent phase. For both IAPP and Aβ, the time courses of surface-activity measurements commenced at the beginning of the reaction, when we can safely assume that the solution contained no amyloid fibrils. This partitioning revealed that at low concentration (0.6 μM), the surface activity of IAPP and Aβ precursors in the whole reaction could be attributed entirely to the surface-adsorbed precursors, with depletion of species in the bulk due to adsorption at the AWI (Fig. 2, A and E). Indeed the surface activity of the surface fraction was either nonsignificantly different from (IAPP, Fig. 2 A) or very close to (Aβ, Fig. 2 E) the starting surface activity of the whole reaction, and the bulk fraction did not display any surfactant activity (equivalent to that of buffer alone, ∼0.1 ΔOD). After partitioning, only a negligible amount of precursors was left in the bulk fraction, which was insufficient in replenishing the newly created AWI. However, above a concentration threshold (1.2 and 4 μM IAPP, or 4 μM Aβ), the bulk and surface fractions had identical surface activities, which was significantly different to that of the whole starting reaction (Fig. 2, B and F). Therefore, not only was the amount of amyloid precursors in the original bulk fraction high enough to adsorb onto the newly created AWI, but also to recreate an absorbed layer with indistinguishable surfactant activity to that of the surface fraction.

Out of convention, we called critical assembly concentration (CAC) the “inflection point” when the bulk concentration started to rise and was able to replenish a newly created AWI. However, it has to be noted that our partitioning technique and our study of the bulk and surface fractions do not depend on the existence of a CAC. Therefore, the CAC for IAPP lies between 0.6 (no replenishment of the AWI by the bulk fraction) and 1.2 μM (replenishment of the AWI by the bulk fraction). Similarly for Aβ, one can conclude that the CAC lies between 0.6 and 4 μM. The estimate of CAC also allows us to provide an upper bound on the CFC. Because amyloid precursors only exist transiently and will eventually transform into fibrils, fibrils are more thermodynamically favorable than these precursors (28). In other words, by comparison to the precursors, the fibrillar species are capable of converting more monomers into the fibrillar form. As a result, CFC < CAC < 1.2 μM for IAPP and CFC < CAC < 4 μM for Aβ.

We confirmed our surface-activity measurements by determining the ability of the bulk and surface fractions of 0.6 and 4 μM IAPP solutions to lower the surface tension of water. The bulk fraction of a 0.6 μM IAPP solution caused no changes to the surface tension of water over the time course, with an average of 69.5 mN/m, which demonstrates an absence of surface activity (Fig. 2 C). The corresponding surface fraction progressively lowered the surface tension of water over the time course, starting at 64.8 mN/m and finishing at 49.9 mN/m, reflecting the highly surface-active nature of the surface fraction. Contrarily to 0.6 μM IAPP, both the surface and bulk fractions of a 4-μM IAPP solution were highly surface-active, with the surface tension of water being lowered over the time course (from 67.5 to 47.9 mN/m for the surface, and 69.0 to 50.5 mN/m for the bulk) (Fig. 2 D).

These surface tension measurements gave identical conclusions to and fully corroborate the surface-activity measurements (ΔOD). We were not able to measure the changes in surface tension for longer time courses by drop-shape analysis as the drop detached itself from the tip of the needle due to the high surface activity of IAPP, and liquid evaporation from the drop became too important over time to exclude any peptide concentration effect on surface tension. Therefore, the quantitative surface tension measurements were able to capture detailed changes in surface activity of IAPP for a short period of time but were not suitable for longer time course analysis, which was made possible by performing qualitative surface-activity measurements (ΔOD). These experimental results indicate that amyloid precursors are highly surface-active and strongly adsorb to the AWI.

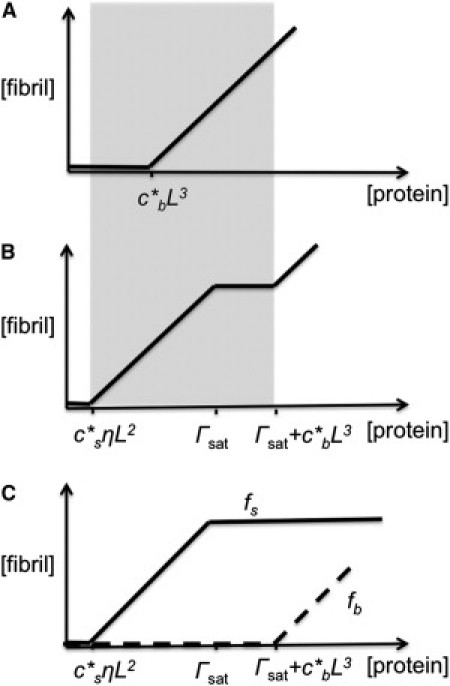

Amyloid fibrillization is dependent on the CFC and interfacial saturation (theory)

We then focused our modeling on strong adsorption. In the absence of the AWI, the total number of peptides (i.e., monomers) in the fibrillar form is (Fig. 3 A),

where, as before, N is the total number of peptides in the system. We assume that peptides only exist in the bulk solution after the maximum adsorbed amount is reached. We denote this amount of interfacial saturation by Γsat. Under this assumption, we can quantitatively follow the evolution of fibrillization as a function of the amount of peptides in the system (Fig. 3, B and C). Before interfacial saturation, i.e., when N < Γsat, the amount of adsorbed peptides is equal to N, i.e., Γ = N. The amount of fibrils is, therefore,

This relationship between peptide amount and fibrillization amount remains the same until N reaches Γsat. After that, the bulk solution begins to be populated with peptides. As N continues to grow, the total number of monomeric peptides in the bulk solution will surpass the L3 where is the bulk CFC. As a result, bulk fibrillization will occur. In other words, we have for N ≥ Γsat,

The overall evolution of the total amount of fibrils in the system is depicted in Fig. 3 B. Note that since L ≫ η and ≈ (see Materials and Methods), we expect that fibrillization will require a much lower amount of peptides in the system in the presence of the AWI (see Fig. 3, A and B, in which the shaded area represents the region of high fibrillization).

Figure 3.

Fibrillization amounts in the absence and presence of the AWI according to the model in the limit of high adsorption. (A) In the absence of AWI, fibrillization occurs when the total number of monomeric peptides surpasses L3, where is the bulk CFC. (B) At the AWI, fibrillization occurs first due to the higher concentration of peptides at the AWI. After the surface is saturated with peptide (when the amount of peptides at the AWI is Γsat), the fibrillization amount remains constant until the total number of monomeric peptides in the bulk goes beyond L3, and then the fibrillization in the bulk starts and so the growth of fibrils continues. (Shaded area) Regime in which the fibrillization amount at the AWI is higher than the amount in the absence of the AWI. (C) The amount of fibrils at the surface (fs) and in the bulk (fb).

This simple model thus connects the surface-active nature of the amyloid-forming peptides with the AWI-dependent fibrillization observed experimentally (Fig. 1). Importantly, our model predicts that the surface activity of the amyloid-forming peptides should render the amount of peptides per volume at the AWI much higher than ηL2, where is the surface CFC (at which point the amount of peptides above the quantity ηL2 should all be converted into fibrils). This in turn should lead to a substantial increase in fibrillization by spatially concentrating the amount of peptides. It has to be noted that although there are parameters in our model that cannot be estimated accurately (e.g., CFC and Γsat), the model itself predicts qualitative changes in the experimental observations, which are not sensitive to the actual values of the parameters. We are providing a generic model that does not depend on the identity of the peptide or protein and therefore can be applied to other systems.

The majority of the final amyloid fibrillar assembly adsorb onto the AWI

Our theoretical approach indicated that the amount of fibrils in the system should depend strongly not only on the adsorption strength but also on the CFC and the interfacial saturation. Therefore, we quantitatively measured the level of fibrils adsorption by performing both surface activity and ThT fluorescence measurements on IAPP. These surface-activity measurements would allow us to monitor the surface adsorption level as Γ is expected to be anticorrelated with surface activity (29). The extent of IAPP fibrillization was first followed by measuring the changes in ThT fluorescence until the reaction reached plateau (i.e., a final fibrillar assembly, at a dynamic equilibrium with the monomeric concentration, was reached) (data not shown, but would be equivalent to the reaction at 12 h in Fig. 1). Then the dynamic surfactant activity of such fibrillized IAPP reaction was measured before and after partitioning of the bulk fraction from the surface (Fig. 4). ThT is a typical amyloid dye that intercalates into stacked β-sheets, implying that ThT should not associate with amyloid monomers and should be only marginally incorporated into small amyloid assemblies, hence no signal at the start of a reaction (30). Therefore, in a fibrillar amyloid assembly at equilibrium, the majority of ThT fluorescence should be associated with the fibrils and not with any remaining monomers at equilibrium. Thus, measuring ThT fluorescence intensity is a good indicator of the presence of amyloid fibrils and enabled us to track where fibrils partitioned after separation of the bulk and surface fractions.

Figure 4.

Amyloid fibrils are surface-active. Dynamic measurement of the surface activity of a fibrillized IAPP reaction at 4 (A) and 40 μM (B) were measured before and after partitioning of the bulk fraction from the surface. (Inset, B) ThT fluorescence changes monitored over time of the bulk fraction after partitioning of a 40 μM IAPP fibrillized reaction. (C) The surface activity of a fibrillized IAPP reaction at several concentrations was measured before and after partitioning of the bulk fraction from the surface. (D) The ThT fluorescence of a fibrillized IAPP reaction at several concentrations was measured before and after partitioning of the bulk fraction from the surface. ΔOD calculations were as described in Materials and Methods. The term a.u. is “arbitrary units”. The mean of at least three independent assays is shown. Error bars represent mean ± SE. (Asterisk) p < 0.05 and (double-asterisk) p < 0.02 for all time points of the time course.

Before partitioning, IAPP fibrillar end-products at various concentrations strongly adsorb, to a similar extent, to a surface layer at the AWI (Fig. 4). After partitioning, the surface activity and the ThT fluorescence of a 4 μM fibrillized IAPP reaction were still associated with the surface fraction (Fig. 4, A and D). Indeed, the bulk fraction was not surface-active (equivalent to that of buffer alone, ∼0.1 ΔOD) and did not display any ThT fluorescence, after partitioning. The difference of surfactant activity and ThT fluorescence between the starting fibrillized whole reaction and the partitioned surface fraction could be due to a loss of fibrillar material (e.g., resolubilization and breakage of the fibrils during the partitioning process). In contrast, the surface activity of a 40 μM fibrillized IAPP reaction after partitioning was associated with both the surface and bulk fractions, whereas the ThT fluorescence was still only associated with the surface fraction (Fig. 4, B and D).

Because no ThT fluorescence was observed for the bulk fraction, we can assume that only monomers or non-ThT binding species were present in the bulk solution. We monitored over time the ThT fluorescence of the bulk fraction to assess whether these non-ThT binding and surface-active species were able to form new fibrils (Fig. 4 B, inset). A ThT fluorescence signal was observed with a plateau being reached ∼12 h. However, the ThT fluorescence was ∼35-fold lower than that of the starting reaction (∼0.6 × 103 and ∼21 × 103 arbitrary units, respectively; Fig. 4 B, inset, and D). Therefore, the surface activity and ThT data suggest that there was sufficient amount of amyloid precursors in the original bulk fraction of the 40-μM fibrillized IAPP to adsorb onto the newly created AWI, to form a surface-active adsorbed layer and to reform fibrils.

When several concentrations of fibrillized IAPP reactions were investigated, the surface activities for both the starting material and surface fraction for each solution remained constant and were not statistically different to one another (except the surface fraction for 30 μM, p < 0.04240 μM) (Fig. 4 C). In contrast, the surface activity of the bulk fraction increased with the concentration of fibrillized IAPP (p < 0.05 for 6 and 30 μM when compared to the concentration below). Moreover, the surface activity of the bulk fraction ceased to be different to that of the surface fraction at 30 and 40 μM fibrillized IAPP reactions. Thus, there is concentration dependence of the surface replenishment by the bulk, which is due to different concentrations of monomers or precursors in the system.

These results indicate that not only amyloid precursors but also fibrils are surface-active and strongly adsorb at the AWI. Moreover, we can also correlate our experimental data with the modeling of Fig. 3. At 4 μM fibrillized IAPP reaction, all fibrils were associated with the surface and no amyloid species were left in the bulk fraction after partitioning (Fig. 4 A). However, at 6 μM fibrillized IAPP reaction, surface replenishment by the bulk fraction started to occur after partitioning, which indicates that Γsat is between 0.0004 and 0.0006 μmol (4 and 6 μM in 100 μL reaction volume) (Fig. 4 C). Above 6 μM, the replenishment of the surface by the bulk fraction kept increasing until the surface activity associated with the partitioned bulk fraction became identical to that of the surface fraction (∼40 μM). At every concentration tested right after partitioning, the ThT fluorescence was always associated with the surface fraction, which was similar to that of the starting reaction (Fig. 4 D).

The presence of ThT fluorescence, in the surface fraction of all the IAPP concentrations tested, demonstrates that fibrils are present at the AWI. The fact that fibrillization occurs at the AWI is direct evidence that the concentration of monomers at the AWI was beyond the CFC. This also suggests that the bulk fraction contained only monomers or non-ThT positive species. Therefore, Γsat + L3 (or the bulk CFC) has not been reached experimentally and is superior to 0.004 μmol. We assume that there is a sharp drop in the protein concentration away from the AWI. The change in concentration is assumed to be rapid, as expected from other experimental systems such as surfactants in solution (27).

Amyloid assembly at the AWI likely follows a three-dimensional system for protein adsorption (multilayer arrangement)

The displacement of interfacial water molecules by adsorbing amyloid species would limit the amount of peptide that can adsorb. Conversely, the interface must have a thickness no less than molecular dimensions. The capacity of amyloid to adsorb at the AWI is not only dependent on the AWI surface area but also on the amyloid size. The relationship between the AWI capacity and the amyloid size may give indication on the arrangement of adsorbed amyloids within the AWI surface region. Knowing that IAPP is 37 residues in length, we performed a rough estimate on how much the AWI is covered with IAPP. According to Knowles et al. (31), a generic amyloid-forming protein that is in the fibrillar form would have a volume of ∼0.17 nm3 per amino acid. Although the IAPP used in Fig. 2 was in the form of precursors and not fibrils, we still employed this estimate because it would provide a good comparison to our analysis of Fig. 4. However, it is worth noting that we expect this to strongly underestimate the actual thickness of the adsorbed layer because we assume that all the proteins are tightly packed as in the case of proteins in the fibrillar form.

With this assumption, at an IAPP concentration of 4 μM (corresponding to the concentration used in Fig. 2 B), the 200 μL reaction volume would contain a total of 3.0 × 10−12 m3 IAPP (4 μM × 200 μL × 6 × 1023 mol−1 × 37 × 0.17 nm3). If we assume that this volume of protein acted as a perfectly malleable fluid with no hydration, it would cover the AWI of the well (3.5 mm in radius) with a depth of ∼78 nm (3.0 × 10−12 m3/((3.5 mm)2 × π)), which is much larger than the diameter of a monomeric IAPP protein. Therefore, we naturally expect that the surface-adsorbed layer cannot accommodate all of the proteins in solution, which is indeed shown to be the case because the bulk fraction contains enough proteins to replenish the surface layer upon partitioning (Fig. 2 B). Note that, in this estimate, we have ignored the modification of the surface area due to the curvature of the meniscus, as such an effect will not affect the qualitative conclusion of our analysis.

For a 40 μM IAPP reaction (corresponding to the concentration used in Fig. 4 B), the species present in the bulk solution after partitioning were able to form only a very few amyloid fibrils (inset in Fig. 4 B), which indicates that most fibrils were originally surface-adsorbed. If we perform similar thickness analysis as before for the adsorbed layer at this concentration, we find that the thickness is 780 nm. Note that the average width and length of an IAPP amyloid fibril were previously found to be ∼10 nm and ∼1 μm, respectively (32). This suggests that the adsorption layer of IAPP at the AWI may form a meshwork structure induced by fibril-fibril interactions. In other words, the adsorption may not be in a monolayer arrangement as in the case of a typical surfactant system (31). Instead, the IAPP adsorption layer may have multiple layers and thus is of the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller adsorption type, which is a generalization of the Langmuir adsorption model that allows for multilayer adsorption (29).

Previous studies showed that the experimental adsorbent capacity of proteins is much higher than the theoretical ratio above which proteins would not absorb anymore (6). Parhi et al. (6) and Barnthip et al. (33) concluded that protein adsorbed at interfaces occupy a surface area much greater than a single monolayer, and favored a three-dimensional system for protein adsorption. This three-dimensional adsorption was described as containing three major steps, as follows: When the surface is created, the transport of molecules to the interface is governed by bulk diffusion. Subsequently the surfactant adsorbs onto the interface and decreases the surface tension. The crowding occurring at the interface will then trigger a conformational change during which the adsorbed molecules begin to align themselves at the interface (7). This conformation change may lead to intermolecular attractions between molecules, which in turn could result to cooperative adsorption and the formation of interfacial multilayers (6,8). Thus, the adsorbed IAPP layer at the interface may provide an environment different to the surrounding bulk solution for IAPP bulk species in its vicinity. This could lead to attractive interactions between the adsorbed layer and these adjacent bulk species and therefore to the formation of multiple interfacial layers.

Amyloid fibrillar assembly adsorbs more strongly to the AWI than precursors

Interestingly, a comparison between Figs. 2 B and 4 A suggests that the adsorption at the AWI of nonfibrillar and fibrillar IAPP were substantially different. Indeed at 4 μM, IAPP precursors from the bulk fraction were able to adsorb to the newly created AWI after partitioning (Fig. 2 B). This was not observed in the case of a 4 μM fibrillized IAPP reaction at equilibrium, for which the bulk fraction failed to replenish the AWI after partitioning (Fig. 4 A). Specifically, it is demonstrated that IAPP fibrils are more strongly adsorbed at the AWI than the nonfibrillar IAPP because the bulk fraction of the fibrillized sample has lost its ability to replenish the adsorption layer when put into a new well. In other words, when IAPP is fibrillized, the precursor pool in the bulk becomes substantially more depleted. Thus, altogether our experimental results strongly confirm the powerful surface partitioning of both amyloid peptide precursors and fibril products into the surface layer when an AWI is present. Partitioning results, together with fibril volume estimation, suggest that this surface layer may consist of a mesh work of fibrils, extending tens of fibril diameters into the hydrophilic aqueous phase. This suggests that amyloid formation depends critically on the characteristics of the interface and the strength of amyloid adsorption to it.

Conclusion

We showed theoretically that interfacial characteristics and the strength of amyloid adsorption are key driving forces behind amyloid assembly. Our model also predicted that the majority of precursors and assembled fibrils should partition into a surface layer. We verified this prediction experimentally by demonstrating that both amyloid precursors (prefibrillar) and fibrillar species strongly adsorbed at the AWI. These novel, to our knowledge, results have very significant implications for understanding amyloid fibril assembly processes in vitro (an environment highly relevant to drug screening) and during pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders in vivo, where other more complex interfaces abound.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nick Hardy of Biolin Scientific UK and Richard Berwick for technical contributions, and Saul Ares for helpful comments.

L.J. was supported by a research grant from Synaptica Ltd.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Chiti F., Dobson C.M. Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006;75:333–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harper J.D., Lansbury P.T., Jr. Models of amyloid seeding in Alzheimer's disease and scrapie: mechanistic truths and physiological consequences of the time-dependent solubility of amyloid proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1997;66:385–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soreghan B., Kosmoski J., Glabe C. Surfactant properties of Alzheimer's Aβ peptides and the mechanism of amyloid aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:28551–28554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cottingham M.G., Bain C.D., Vaux D.J. Rapid method for measurement of surface tension in multiwell plates. Lab. Invest. 2004;84:523–529. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopes D.H., Meister A., Winter R. Mechanism of islet amyloid polypeptide fibrillation at lipid interfaces studied by infrared reflection absorption spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2007;93:3132–3141. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.110635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parhi P., Golas A., Vogler E.A. Volumetric interpretation of protein adsorption: capacity scaling with adsorbate molecular weight and adsorbent surface energy. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6814–6824. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu H., Fan Y., Sui S.F. Induction of changes in the secondary structure of globular proteins by a hydrophobic surface. Eur. Biophys. J. 1993;22:201–205. doi: 10.1007/BF00185781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krishnan A., Siedlecki C.A., Vogler E.A. Traube-rule interpretation of protein adsorption at the liquid-vapor interface. Langmuir. 2003;19:10342–10352. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epand R.M., Vogel H.J. Diversity of antimicrobial peptides and their mechanisms of action. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1462:11–28. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00198-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sato H., Feix J.B. Peptide-membrane interactions and mechanisms of membrane destruction by amphipathic α-helical antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1758:1245–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terzi E., Hölzemann G., Seelig J. Interaction of Alzheimer β-amyloid peptide(1-40) with lipid membranes. Biochemistry. 1997;36:14845–14852. doi: 10.1021/bi971843e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jean L., Lee C.F., Vaux D.J. Competing discrete interfacial effects are critical for amyloidogenesis. FASEB J. 2010;24:309–317. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-137653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chi E.Y., Frey S.L., Lee K.Y. Amyloid-β fibrillogenesis seeded by interface-induced peptide misfolding and self-assembly. Biophys. J. 2010;98:2299–2308. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang D., Dinh K.L., Zhou F. A kinetic model for β-amyloid adsorption at the air/solution interface and its implication to the β-amyloid aggregation process. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:3160–3168. doi: 10.1021/jp8085792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morinaga A., Hasegawa K., Naiki H. Critical role of interfaces and agitation on the nucleation of Aβ amyloid fibrils at low concentrations of Aβ monomers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1804:986–995. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris V.K., Ren Q., Sunde M. Recruitment of class I hydrophobins to the air:water interface initiates a multi-step process of functional amyloid formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:15955–15963. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.214197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen C.L., Murphy R.M. Solvent effects on self-assembly of β-amyloid peptide. Biophys. J. 1995;69:640–651. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79940-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snyder S.W., Ladror U.S., Holzman T.F. Amyloid-β aggregation: selective inhibition of aggregation in mixtures of amyloid with different chain lengths. Biophys. J. 1994;67:1216–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80591-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diamant S., Podoly E., Soreq H. Butyrylcholinesterase attenuates amyloid fibril formation in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:8628–8633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602922103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marek P., Abedini A., Raleigh D.P. Aromatic interactions are not required for amyloid fibril formation by islet amyloid polypeptide but do influence the rate of fibril formation and fibril morphology. Biochemistry. 2007;46:3255–3261. doi: 10.1021/bi0621967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knight J.D., Miranker A.D. Phospholipid catalysis of diabetic amyloid assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;341:1175–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foderà V., Librizzi F., Leone M. Secondary nucleation and accessible surface in insulin amyloid fibril formation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:3853–3858. doi: 10.1021/jp710131u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee C.F. Isotropic-nematic phase transition in amyloid fibrillization. Phys. Rev. E. 2009;80:031902. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.80.031902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Nuallain B., Shivaprasad S., Wetzel R. Thermodynamics of A β(1-40) amyloid fibril elongation. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12709–12718. doi: 10.1021/bi050927h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szymczyk K., Zdziennicka A., Wójcik W. The wettability of polytetrafluoroethylene and polymethyl methacrylate by aqueous solution of two cationic surfactants mixture. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006;293:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2005.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Israelachvili J.N. Academic Press; London, England: 1991. Intermolecular and Surface Forces. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnes G.T., Gentle I.E. Oxford University Press; Oxford, England: 2005. Interfacial Science: An Introduction. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee C.F. Self-assembly of protein amyloids: a competition between amorphous and ordered aggregation. Phys. Rev. E. 2009;80:031922. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.80.031922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butt H.J., Graf K., Kappl M. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2003. Physics and Chemistry of Interfaces. [Google Scholar]

- 30.LeVine H., 3rd Thioflavine T interaction with synthetic Alzheimer's disease β-amyloid peptides: detection of amyloid aggregation in solution. Protein Sci. 1993;2:404–410. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knowles T.P., Fitzpatrick A.W., Welland M.E. Role of intermolecular forces in defining material properties of protein nanofibrils. Science. 2007;318:1900–1903. doi: 10.1126/science.1150057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larson J.L., Miranker A.D. The mechanism of insulin action on islet amyloid polypeptide fiber formation. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;335:221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barnthip N., Noh H., Vogler E.A. Volumetric interpretation of protein adsorption: kinetic consequences of a slowly-concentrating interphase. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3062–3074. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.