Abstract

Recent research has demonstrated that “self-imagination” – a mnemonic strategy developed by Grilli and Glisky (2010) – enhances episodic memory in memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage more than traditional cognitive strategies, including semantic elaboration and visual imagery. The present study investigated the effect of self-imagination on prospective memory in individuals with neurologically-based memory deficits. In two separate sessions, 12 patients with memory impairment took part in a computerized general knowledge test that required them to answer multiple choice questions (i.e. ongoing task) and press the “1” key when a target word appeared in a question (i.e. prospective memory task). Prior to the start of the general knowledge test in each session, participants attempted to encode the prospective memory task with one of two strategies: self-imagination or rote-rehearsal. The findings revealed a “self-imagination effect (SIE)” in prospective memory as self-imagining resulted in better prospective memory performance than rote-rehearsal. These results demonstrate that the mnemonic advantage of self-imagination extends to prospective memory in memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage and suggest that self-imagination has potential in cognitive rehabilitation.

Keywords: Self-referential processing, Implementation intentions, Memory rehabilitation, Brain damage

Emerging research suggests that “self-imagination” – the imagination of an event from a personal perspective – may be a particularly successful mnemonic strategy in memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage. In an initial study, Grilli and Glisky (2010) demonstrated that self-imagination enhanced recognition memory more than semantic elaboration in memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage and healthy individuals. Additional findings from that study revealed that the advantage of self-imagination, what Grilli and Glisky have called the “self-imagination effect (SIE),” was not affected by memory functioning as measured by the general memory index (GMI) of the Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS-III; Wechsler, 1997), although benefits of semantic elaboration were smaller in individuals with poorer memory functioning. In a follow-up study, Grilli and Glisky (in press) demonstrated that the SIE extended to a cued recall memory task, was preserved after a relatively long delay (i.e. 30 minutes), and, similar to recognition memory, was not limited by severity of memory impairment in individuals with neurological damage.

Because memory performance following self-imagining has been shown to be greater than that following elaborative semantic processing, visual imagery, and other-person processing (Grilli & Glisky, 2010; in press), Grilli and Glisky have proposed that the advantage of self-imagining may be attributable to mnemonic mechanisms related to the self, which may be preserved in individuals with neurological damage (Klein, Cosmides, Costabile, & Mei, 2002; Marquine, 2009; Rathbone, Moulin, & Conway, 2009). Indeed, patient studies have revealed that aspects of self-knowledge remain intact in at least some memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage (for a review, see Klein, 2004). For instance, Cermak and O’Connor (1983) observed that patient S.S. – a 50 year-old man who developed severe retrograde and anterograde amnesia after he contracted herpes simplex encephalitis – based autobiographical memory retrieval exclusively on a “personal pool of generalized knowledge about himself” (p. 230). Similarly, Rathbone, Moulin, and Conway (2009) recently demonstrated that patient P.J.M., a 38 year-old woman with retrograde amnesia, could retrieve facts about herself such as “I am an academic” and “I am a mum,” despite a severely impaired ability to remember events from which these facts were derived. Further evidence of spared self-knowledge in memory-impaired individuals comes from a series of neuropsychological case studies conducted by Klein and colleagues (for a review, see Klein & Gangi, 2010). These studies have demonstrated that knowledge of one’s own personality traits remains intact in individuals with severe memory impairments of various etiologies including traumatic brain injury (Klein, Loftus, & Kihlstrom, 1996). Based on these neuropsychological findings, Klein and colleagues (Klein, Cosmides, Costabile, & Mei, 2002) posited that specialized learning systems might support the acquisition and retrieval of trait self-knowledge in memory-impaired individuals. Strategies that capitalize on preserved cognitive functions to compensate for memory impairment have improved performance on a variety of memory tasks in individuals with neurological damage (Baddeley & Wilson, 1994; Evans et al., 2000; Glisky, 2004; Wilson & Kapur, 2008). Therefore, because self-imagination may draw upon mnemonic mechanisms that are intact in many brain-injured individuals, benefits of self-imagination may extend to other types of memory that are often impaired by neurological damage.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that prospective memory – remembering to perform a task at a future point in time – is often impaired in individuals with neurological damage (Cockburn, 1995; Schmitter-Edgecombe & Wright, 2004; Shum, Valentine, & Cutmore, 1999). Impaired prospective memory may be partly related to deficits in executive functions which are thought to be important for “remembering to remember,” including monitoring the environment for cues and interrupting ongoing activity to perform a delayed intention. However, impaired retrospective memory function – particularly in individuals with severe memory deficits – also may negatively affect prospective memory performance. Indeed, if the content of a future task is not sufficiently retained in memory, prospective memory failure is likely. Although prospective memory performance among memory-impaired individuals has been shown to benefit from rehabilitation programs, previous research indicates that these programs can be relatively time-consuming and effort intensive (Kinsella, Ong, Storey, Wallace, & Hester, 2007; Kixmiller, 2002). Therefore, uncovering additional, more efficient strategies for improving prospective memory in individuals with neurological damage may have significant clinical implications.

One such efficient strategy that has been shown to improve prospective memory among a variety of populations is known as “implementation intentions” (Chasteen, Park, & Schwarz, 2001; Cohen & Gollwitzer, 2008; Liu & Park, 2004). Implementation intentions rely upon the creation of an association between a desired action and the future context in which that action should be completed, and typically take the form of an “if, then” statement (e.g., “If I see X, then I will do Y”). In several recent studies, the “if, then” statement of an implementation intention has been augmented with a brief period of imagining (Chasteen, Park, & Schwarz, 2001; McDaniel, Howard, & Butler, 2008; McFarland & Glisky, in press; Meeks & Marsh, 2010). By encouraging participants to imagine themselves completing a specific task in a future context, this form of implementation intention is akin to self-imagining, and has been shown to improve prospective memory. Importantly with respect to the purposes of the current study, improved prospective memory has been reported in two of the three studies that have included an “imagery-only” condition (McFarland & Glisky, in press; Meeks & Marsh, 2010), suggesting that the development of an “if, then” statement is not necessary to improve prospective memory and that the use of imagery alone can produce positive effects. Both of those studies included only healthy young adults, however, and did not investigate the effects of imagery among memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage.

The principal aim of the present study was to investigate the effectiveness of self-imagining in improving prospective memory in memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage. Therefore, we employed a self-imagining technique that was designed to bind an intended future action with self-relevant, situational cues that could later signal the appropriate time to execute the retrieved intention. Based on previous research, self-imagining was hypothesized to enhance prospective memory to a greater degree than rote-rehearsal.

Method

Participants

Twelve individuals (7 male/5 female) with neurological damage of mixed etiology (9 with traumatic brain injury [TBI]) participated in the study. Individuals were recruited from the pool of participants in our laboratory and from brain injury support groups in the greater Tucson, Arizona area. To be included in the study, individuals had to have a memory impairment, which was defined as at least a one standard deviation (i.e. 15 point) difference between estimated pre-morbid IQ (NAART; Spreen & Strauss, 1998) and memory functioning as determined by GMI scores, and be at least one year post-trauma. All individuals were at least 1.5 years post-injury at time of testing and deemed to be cognitively stable at that time. Table 1 displays demographic information and neuropsychological test performance for each participant.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics and Neuropsychological Data for Patients

| Patient | Etiology | Neurological Damage |

Years Since Injury |

Gender | Age | IQ | GMI | EF Composite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TBI (MVA) | rFL/rTL | 9 | Female | 81 | 114 | 67 | −0.14 |

| 2 | TBI (MVA) | 16 | Female | 53 | 103 | 63 | −1.54 | |

| 3 | TBI (MVA) | rFL/rTL/Diffuse | 24 | Male | 44 | 125 | 110 | 0.76 |

| 4 | TBI (MVA) | rFL/diffuse | 29 | Female | 53 | 125 | 96 | 0.23 |

| 5 | TBI (MVA) | 32 | Male | 50 | 97 | 78 | −1.31 | |

| 6 | Anoxia | 36 | Female | 54 | 98 | 79 | −1.42 | |

| 7 | TBI (MVA) | FLs/rTL/mPL | 18 | Male | 67 | 104 | 69 | −1.38 |

| 8 | Aneurysm | FLs | 22 | Male | 46 | 127 | 81 | 1.51 |

| 9 | TBI (Fall) | 18 | Male | 42 | 107 | 70 | −1.39 | |

| 10 | TBI (MVA) | FLs/rTL/Diffuse | 11 | Female | 47 | 118 | 98 | −0.79 |

| 11 | TBI (Fall) | 23 | Female | 38 | 98 | 81 | 0.01 | |

| 12 | Tumor | rTL/hypothalamus | 16 | Female | 18 | 101 | 57 | −0.73 |

| Mean | 21.17 | 49.42 | 110 | 79.08 | −0.52 | |||

| Standard Deviation | 8.18 | 15.29 | 11.48 | 15.62 | 0.99 | |||

Notes. TBI = traumatic brain injury; r = right; l = left; FL = frontal lobe; TL = temporal lobe; EF = executive function; MVA = motor vehicle accident

Neuropsychological Functioning

Participants were administered a battery of neuropsychological tests designed to measure intellectual function (i.e. NAART) and memory function (i.e. GMI from the WMS-III), and to construct a composite measure of executive function. The composite measure of executive function was based on five tests previously found to cluster together in factor analysis (Glisky et al., 1995, 2001) and hypothesized to reflect some aspects of executive function associated with working memory (Glisky & Kong, 2008). The neuropsychological tests of executive function included the Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) (Hart, Kwentus, Wade, & Taylor, 1988), Mental Control (WMS-III), Mental Arithmetic from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised (WAIS-R) (Wechsler, 1981), the FAS test of word fluency (Spreen & Benton, 1977), and Digit Span Backwards (WMS-III). The composite score for each individual represents the unweighted average of the z-scores for the five tests. Z-scores were derived from published normative data for each neuropsychological test. As shown in Table 1, a majority of the patients had moderate to severe memory deficits and variable executive functioning.

Materials

The experimental paradigm included a computerized ongoing task that required participants to complete multiple choice questions of general knowledge (McDaniel, Glisky, Rubin, Guynn, & Routhieaux, 1999). Each question was one or two sentences in length and had four answer choices labeled A, B, C or D. Questions were randomly mixed for each participant and presented visually on a Dell laptop computer with DMDX (Forster & Forster, 2003).

Procedure

Participants provided written informed consent prior to taking part in the study, and all data were collected in compliance with regulations of the University of Arizona Institutional Review Board. The study was divided into two sessions administered one week apart. In each session, participants completed a 42-minute version of the general knowledge test. Each question in the general knowledge test appeared alone in the middle of the screen for 4 seconds. The answer choices then appeared below the question for a total of 8 seconds. Participants indicated their response by pressing one of four keys labeled A, B, C, or D. Feedback was provided following each trial (i.e. correct or incorrect), and the correct answer indicated if they had selected incorrectly. Embedded within the trivia task were eight questions containing either the target word “president” or the target word “state.” For a given participant, the same target word appeared in all eight questions, and target words were counterbalanced across sessions and encoding condition. Questions containing the target word were separated by approximately 5-minute intervals. Participants were introduced to the layout of the general knowledge test and given four practice trials. After the practice trials, participants were told that one of their goals was to answer each trivia question to the best of their ability. In addition, participants were told “we are also interested in testing your ability to remember to perform a task in the future. Therefore, please press the ‘1’ key each time the word ‘president’ (or ‘state’) appears in a trivia question.”

Each session included a different encoding condition, which was administered after participants were given the prospective memory instructions. In the self-imagining condition, participants were instructed to imagine taking part in the trivia game, seeing a question containing the target word, and immediately pressing the “1” key. Participants were instructed to imagine the event from their own personal perspective with as much detail as possible for 45 seconds. In the rote-rehearsal condition, participants were instructed to rehearse aloud the following statement for 45 seconds: “Press the 1 key when the word ‘president’ (or ‘state’) appears in a question.”

After completing the encoding condition, participants took part in a 12-minute distracter task, which involved studying and recalling a list of 16 concrete nouns. The general knowledge test was started after the 12-minute delay, and no reminder of the prospective memory task was provided. Upon completing the general knowledge test, participants were asked to describe the tasks that they were performing during the session (i.e. answering multiple choice questions, pressing 1 if the target word appeared) to assess whether they remembered the prospective memory task. The order of encoding conditions was counterbalanced such that half the participants were administered the self-imagining condition in session one and the rote-rehearsal condition in session two and half took part in the rote-rehearsal condition in session one and the self-imagining condition in session two. Target words (i.e. president or state) were counterbalanced across session and encoding condition.

Results

Effect of Self-Imagining on Prospective Memory

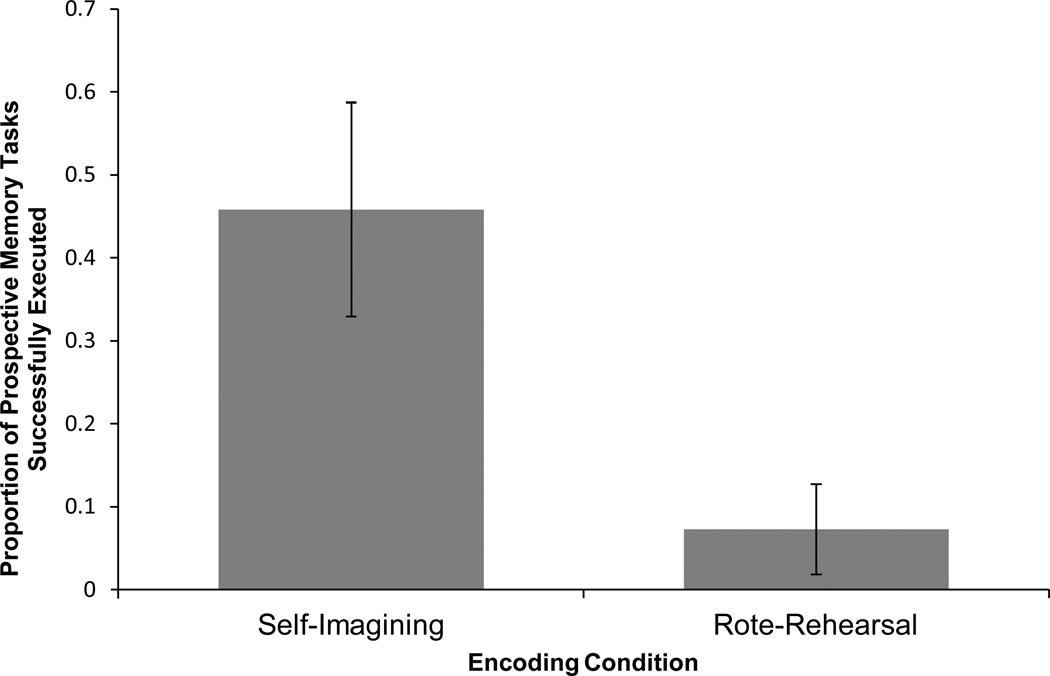

All participants mentioned the prospective memory task in post-experiment debriefing. Figure 1 depicts the mean proportion of prospective memory tasks successfully executed in the rote-rehearsal and self-imagination conditions. A one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed a main effect of encoding condition, F (1, 11) = 11.52, p < .01, η2 = .51. The data show an SIE in prospective memory as self-imagining enhanced prospective memory relative to rote-rehearsal in individuals with neurological damage. The proportion of trivia questions answered correctly in the self-imagining condition did not differ from the proportion of trivia questions answered correctly in the rote-rehearsal condition, t (11) < 1; nor did the total number of questions answered in the self-imagining condition differ from the rote-rehearsal condition, t (11) = 1.1, p = .30. Although the order of encoding conditions was counterbalanced, we ran an additional analysis to investigate whether prospective memory performance was affected by the order of the encoding conditions. This analysis revealed that the order of encoding conditions did not affect prospective memory performance, t (11) < 1.

Figure 1.

Proportion of prospective memory tasks successfully executed in the self-imagining and rote-rehearsal conditions. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean.

Relation of Self-Imagining and SIE to Neuropsychological Functioning

We ran exploratory correlational analyses to investigate whether prospective memory performance following self-imagining was related to memory function as measured by GMI scores or executive function as measured by executive function composite scores. Pearson product-moment correlations revealed that performance in the self-imagination condition was not significantly correlated with memory function, r = .34, p = .28; or executive function, r = .20, p = .53. We also investigated whether the advantage of self-imagination relative to rote-rehearsal (i.e. the SIE) was related to neuropsychological functioning. The SIE was calculated by subtracting performance in the rote-rehearsal condition from performance in the self-imagination condition. Pearson product-moment correlations revealed that the SIE was not significantly correlated to memory function, r = .10, p = .76; or executive function, r = .09, p = .78. Because 10 out of the 12 participants failed to perform a single prospective memory task in the rote-rehearsal condition, we were unable to analyze whether prospective memory performance following rote-rehearsal was related to memory functioning or executive functioning.

Although self-imagination enhanced prospective memory relative to rote-rehearsal, five participants failed to perform a single prospective memory task in the self-imagination condition. These patients, however, also failed to perform a single prospective memory task in the rote-rehearsal condition, and therefore the effect of self-imagining on prospective memory remains unclear in these individuals. We ran several exploratory independent-samples t-tests to investigate whether the individuals who were on the floor in the self-imagination condition differed from the other participants in regards to memory functioning as measured by GMI scores, executive functioning as measured by executive functioning composite scores, age, or IQ. None of the independent-sample t-tests approached significance, all p’s > .18.

Discussion

The principal aim of the present study was to evaluate the potential of self-imagining for improving prospective memory in memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that a brief period of self-imagining improves prospective memory in memory-impaired individuals. The results of the present study were fairly robust. In fact, although only two participants completed a single prospective memory task following rote-rehearsal, seven participants completed a prospective memory task following self-imagining. Furthermore, the magnitude of the effect appears not to be trivial. Indeed, participants who benefited from self-imagining experienced on average a 66 percent advantage in prospective memory performance with self-imagining relative to rote-rehearsal. Note also that the trivia game in which the prospective memory task was embedded occurred after a 12-minute filled delay without any further reminders.

These results, although preliminary, suggest that it might be possible to adapt self-imagining for a rehabilitation setting to help memory-impaired individuals improve prospective memory in real world tasks. Indeed, it may be possible to teach a memory-impaired individual to use self-imagining in order to improve performance on critical tasks in one’s home or vocational setting. For example, in order to remember to take medication in the morning, a memory-impaired patient could be instructed to imagine oneself performing the prospective memory task (i.e. taking medication) immediately after engaging in an event that is part of one’s morning routine (e.g. drinking a cup of coffee). Similarly, it may be possible to apply self-imagining to help memory-impaired individuals associate important vocational tasks with events that – in addition to signaling the appropriate moment to realize a delayed intention – regularly occur in the workplace (e.g. clocking in, lunch break, etc.). Moreover, the fact that the present study used a single 45-second encoding condition emphasizes the potential ease with which benefits of self-imagination may be instantiated in prospective memory.

Although the findings of the present study are promising, several questions remain to be addressed. For instance, from a rehabilitation perspective, additional research should investigate whether the benefits of self-imagination extend beyond the laboratory, and if so, for how long. Furthermore, the present study included only 12 participants, many of whom sustained neurological damage as a result of traumatic brain injuries. Although this sample size far exceeds that of the majority of previous research in this area (for a review, see Shum, Levin, & Chan, 2011), additional studies need to to test the utility of self-imagining in populations with neurological damage of different etiologies. Although the results from the rote-rehearsal condition suggest that prospective memory is impaired in our group of memory-impaired patients, future research should include individuals based on their performance on psychometric tests of prospective memory (e.g. Cambridge Prospective Memory Test [CAMPROMPT], Wilson et al., 2005; the Memory for Intentions Screening Test [MIST], Raskin, 2009). Furthermore, although the present study counterbalanced the order of encoding conditions and did not find an effect of encoding condition order on prospective memory performance, a between-subjects design is a preferable method to account for potential order effects.

Additional research also should attempt to uncover the mechanisms responsible for the benefit of self-imagination in prospective memory. Grilli and Glisky (2010; in press) have suggested that the mnemonic advantage of self-imagination may be partly attributable to mechanisms of the self, which may be preserved in memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage. Thus, one feasible explanation is that the SIE in prospective memory is attributable to self-referential processing. The self-imagination strategy employed in the present study incorporated several components that may have involved the self. For example, self-imagining is believed to involve the generation of thoughts and feelings that are self-relevant and perhaps very memorable. Therefore, when self-imagining, participants may have elicited thoughts and feelings that may have served later as highly accessible retrieval cues for the prospective memory task. In addition, motor simulation may have enhanced performance. Previous research has demonstrated that self-performed tasks are better remembered than tasks performed by others (Rosa & Gutchess, 2011). Therefore, engaging motor imagery when imagining oneself executing the prospective memory task (i.e. reaching forward and pressing the “1” key) may have contributed to the advantage of self-imagination.

However, there are alternative explanations for the cognitive mechanisms of the SIE. For example, the present study did not include a simple visual imagery condition or a non-self-referential condition that required both visual and verbal encoding. We therefore cannot rule out the possibility that the SIE in prospective memory may be attributable to simple visual imagery or a combination of visual and verbal encoding.

As in previous studies, performance following self-imagining was not related to level of memory or executive function. However, given the small sample size, future studies should investigate further the relation of the SIE in prospective memory to neuropsychological functioning. Additional studies also should investigate whether the effectiveness of self-imagination in prospective memory may be enhanced further among brain-injured individuals. A series of errorless learning studies conducted by Clare and colleagues (Clare, Wilson, Breen, & Hodges, 1999; Clare et al., 2000; Clare, Wilson, Carter, Hodges, & Adams, 2001) demonstrate that multiple study/test sessions separated by increasing intervals (i.e. expanded rehearsal) results in substantial benefits in memory-impaired individuals. Therefore, combining self-imagination with expanded rehearsal may generate greater benefits amongst memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage. Alternatively, increasing the duration of the self-imagination session may prove beneficial in some memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage.

Conclusions

The findings of the present study demonstrate that imagining a future task from a personal perspective enhances the ability to remember to perform the task in memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage. Indeed, these findings reveal that self-imagination improves performance among memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage on a cognitively demanding prospective memory task, much like those experienced in everyday life. Furthermore, the findings of the present study suggest that self-imagination holds potential for the rehabilitation of prospective memory.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institute on Aging Grant AG14792. We would like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Glisky for her helpful comments.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

A portion of this research was completed while Craig McFarland was at the VA Boston Healthcare System, Boston, Massachusetts.

References

- Baddeley A, Wilson BA. When implicit learning fails: amnesia and the problem of error elimination. Neuropsychologia. 1994;32(1):53–68. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(94)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cermak LS, O’Connor M. The anterograde and retrograde retrieval ability of a patient with amnesia due to encephalitis. Neuropsychologia. 1983;21(3):213–234. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(83)90039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasteen AL, Park DC, Schwarz N. Implementation intentions and facilitation of prospective memory. Psychological Science. 2001;12(6):457–461. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare L, Wilson BA, Breen K, Hodges JR. Errorless learning of name-face assocations in early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurocase. 1999;5(1):37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Clare L, Wilson BA, Carter G, Breen K, Gosses A, Hodges JR. Intervening with everyday memory problems in dementia of Alzheimer type: an errorless learning approach. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2000;22(1):132–146. doi: 10.1076/1380-3395(200002)22:1;1-8;FT132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare L, Wilson BA, Carter G, Hodges JR, Adams M. Long-term maintenance of treatment gains following a cognitive rehabilitation intervention in early dementia of Alzheimer type: a single case study. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2001;11(3–4):477–494. [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn J. Task interruption in prospective memory: A frontal lobe function? Cortex. 1995;31(1):87–97. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(13)80107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AL, Gollwitzer PM. The cost of remembering to remember: Cognitive load and implementation intentions influence ongoing task performance. In: Kliegel M, McDaniel MA, Einstein GO, editors. Prospective memory. New York: Erlbaum; 2008. pp. 367–390. [Google Scholar]

- Evans JJ, Wilson BA, Schuri U, Andrade J, Baddeley A, Bruna O, et al. A comparison of “errorless” and “trial-and-error” learning methods for teaching individuals with acquired memory deficits. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2000;10(1):67–101. [Google Scholar]

- Forster KI, Forster JC. DMDX: a window display program with millisecond accuracy. Behavioral Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers: a Journal of Psychonomic Society, Inc. 2003;35(1):116–124. doi: 10.3758/bf03195503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisky EL. Disorders of memory. In: Ponsford J, editor. Cognitive and behavioral rehabilitation: From neurobiology to clinical practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 100–128. [Google Scholar]

- Glisky EL, Kong LL. Do young and older adults rely on different processes in source memory tasks? A neuropsychological study. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition. 2008;34(4):809–822. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.34.4.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisky EL, Polster MR, Routhieaux BC. Double dissociation between item and source memory. Neuropsychology. 1995;9:229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Glisky EL, Rubin SR, Davidson PSR. Source memory in older adults: An encoding or retrieval problem? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition. 2001;27:1131–1146. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.27.5.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilli MD, Glisky EL. Self-Imagination enhances recognition memory in memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage. Neuropsychology. 2010;24(6):698–710. doi: 10.1037/a0020318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilli MD, Glisky EL. The self-imagination effect: Benefits of a self-referential encoding strategy on cued recall in memory-impaired individuals with neurological damage. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711000737. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart RP, Kwentus JA, Wade JB, Taylor JR. Modified Wisconsin Cart Sorting Test in elderly normal, depressed, and demented patients. Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1988;2:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella GJ, Ong B, Storey E, Wallace J, Hester R. Elaborated spaced-retrieval and prospective memory in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2007;17(6):688–706. doi: 10.1080/09602010600892824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kixmiller JS. Evaluation of prospective memory training for individuals with mild Alzheimer’s disease. Brain and Cognition. 2002;49(2):237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SB. The cognitive neuroscience of knowing one’s self. In: Gazzaniga MS, editor. The Cognitive Neurosciences III (Third Edition) Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2004. pp. 1077–1089. [Google Scholar]

- Klein SB, Cosmides L, Costabile KA, Mei L. Is there something special about the self? A neuropsycholigical case study. Journal of Research in Personality. 2002;36:490–506. [Google Scholar]

- Klein SB, Gangi CE. The multiplicity of self: neuropsychological evidence and its implications for the self as a construct in psychological research. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1191:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SB, Loftus J, Kihlstrom JF. Self-knowledge of an amnesic patient: Toward a neuropsychology of personality and social psychology. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1996;125(3):250–260. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.125.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LL, Park DC. Aging and medical adherence: the use of automatic processes to achieve effortful things. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19(2):318–325. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquine MJ. Self-knowledge and self-referential processing in memory disorders: Implications for neuropsychological rehabilitation. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 2009;69:4432. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel MA, Glisky EL, Rubin SR, Guynn MJ, Routhieaux BC. Prospective memory: A neuropsychological study. Neuropsychology. 1999;13:103–110. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.13.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel MA, Howard DC, Butler KM. Implementation intentions facilitate prospective memory under high attention demands. Memory & Cognition. 2008;36(4):716–724. doi: 10.3758/mc.36.4.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland CP, Glisky EL. Implementation intentions and imagery: Individual and combined effects on prospective memory among young adults. Memory & Cognition. doi: 10.3758/s13421-011-0126-8. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeks JT, Marsh RL. Implementation intentions about nonfocal event-based prospective memory tasks. Psychological Research. 2010;74:82–89. doi: 10.1007/s00426-008-0223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin S. Memory for intentions screening test: Psychometric properties and clinical evidence. Brain Impairment. 2009;10(1):23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Rathbone CJ, Moulin CJA, Conway MA. Autobiographical memory and amnesia: Using conceptual knowledge to ground the self. Neurocase. 2009;15(5):405–418. doi: 10.1080/13554790902849164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa NM, Gutchess AH. Source memory for action in young and older adults: Self vs. close or unknown others. Psychology and Aging. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0022827. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitter-Edgecombe M, Wright MJ. Event-based prospective memory following severe closed-head injury. Neuropsychology. 2004;18:353–361. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.18.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shum D, Valentine M, Cutmore T. Performance of individuals with severe long-term traumatic brain injury on time-, event-, and activity-based prospective memory tasks. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1999;21(1):49–58. doi: 10.1076/jcen.21.1.49.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shum D, Levin H, Chan RCK. Prospective memory in patients with closed head injury: A review. Neuropsychologia. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreen O, Benton AL. Neurosensory Center Comprehensive Examination for Aphasia (NCCEA) Victoria: University of Victoria Neuropsychology Laboratory; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Spreen O, Strauss E. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Second Edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale-Third Edition: Administration and scoring manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BA, Kapur N. Memory rehabilitation for people with brain injury. In: Stuss DT, Winocur G, Robertson IH, editors. Cognitive Neurorehabilitation: Evidence and Application (Second Edition) New York, NY: Cambridge Press; 2008. pp. 522–540. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BA, Emslie H, Foley J, Shiel A, Watson P, Haw- kins K, Groot Y, Evans J. The Cambridge Prospective Memory Test. London: Harcourt; 2005. [Google Scholar]