Abstract

Centella asiatica (CA), commonly named gotu kola, is an Ayurvedic herb used to enhance memory and nerve function. To investigate the potential use of CA in Alzheimer's disease (AD), we examined the effects of a water extract of CA (GKW) in the Tg2576 mouse, a murine model of AD with high β-amyloid burden. Orally administered GKW attenuated β-amyloid-associated behavioral abnormalities in these mice. In vitro, GKW protected SH-SY5Y cells and MC65 human neuroblastoma cells from toxicity induced by exogenously added and endogenously generated β-amyloid, respectively. GKW prevented intracellular β-amyloid aggregate formation in MC65 cells. GKW did not show anticholinesterase activity or protect neurons from oxidative damage and glutamate toxicity, mechanisms of current AD therapies. GKW is rich in phenolic compounds and does not contain asiatic acid, a known CA neuroprotective triterpene. CA thus offers a unique therapeutic mechanism and novel active compounds of potential relevance to the treatment of AD.

1. Introduction

Centella asiatica (L.) Urban, family Apiaceae (CA), is known as Mandookaparni or Brahmi in Ayurvedic medicine. It is highly regarded as a “rasayana” or rejuvenating herb [1] and is reputed to increase intelligence and memory [1]. The dried herb has enjoyed growing popularity in the USA and other Western countries, where it is sold as the dietary supplement “gotu kola” [2].

Cognitive effects of the aqueous extract of CA (100–300 mg/kg/day) have been evaluated in several rodent studies using standard tests including shuttle box, step-through paradigm, elevated plus maze, and passive avoidance tests. CA extract markedly improved learning and memory of wild-type rats [3], rats subjected to CNS toxicity (intracerebroventricular streptozotocin) [4], and pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) kindled rats [5]. When administered to neonatal mice from day 15 to 30 postpartum, the extract caused significant enhancement in learning efficiency and spatial memory with no effects on locomotor function [6]. Direct neurotropic effects of CA have also been reported. CA aqueous extract caused significant increases in dendritic arborization of apical and basal dendrites in hippocampal neurons of neonatal mice [6] and both adult [7] and neonatal [8] rats. These studies, performed in diverse settings, show that CA water extract has biological effects of relevance to memory, learning, and aging, and potentially to disease progression in Alzheimer's disease (AD).

The present study examines the effect of a water extract of CA on behavioral deficits in the Tg2576 transgenic mouse, a murine model of AD. The Tg2576 or “Hsiao” transgenic mouse has been described in detail [9, 10] and is one of the most widely used animal models of AD. A mutant human amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene inserted into the genome gives rise to age-dependent hippocampal and cortical β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques similar to AD pathology. Plaques are not histologically evident until 10–12 months of age, and plaque pathology is confined to the hippocampus and cerebral cortex. In other words, the age and region dependence of pathology in AD are nicely recapitulated in this strain. Other features of AD reproduced in this strain are astrocytic and microglial activation surrounding the Aβ plaques and dystrophic changes in neurites in the vicinity of plaques [11]. Importantly, these mice display abnormalities in standard behavioral tests. Open-field behavior has been shown to distinguish Tg2576 from wild-type mice, with Tg2576 mice more active in the open field than their wild-type littermates [12]. Hippocampal dysfunction, resulting in impaired spatial memory, is evident in the Morris water maze and has been repeatedly shown to distinguish aged, Aβ plaque-bearing Tg2576 from wild-type mice [9, 13]. These behavioral tests were utilized in the present study.

In addition to in vivo studies, the present work examined possible mechanisms underlying CA effects in the Tg2576 mouse, using in vitro models. The mechanisms examined include cholinesterase inhibition and neuroprotectant effects against oxidative damage, glutamate toxicity, and beta amyloid toxicity. The ingredient compounds in CA aqueous extract were also investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aqueous Extraction of CA

Dried CA was purchased from Oregon's Wild Harvest, Sandy, OR (Batch no. GOT-10072C-OGA). The identity of the herb was verified by means of visual examination and by comparing its thin layer chromatographic profile with that reported in the literature [14]. A dried water extract (GKW) was prepared by refluxing CA (120 g) with water (1.5 L) for 2 hr, filtering to remove plant debris and freeze-drying to yield a residue (11.5 g).

2.2. Chemical Analysis of CA Extracts

Water and ethanolic extracts of CA were compared by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to UV detection (LC-UV) and mass spectrometry (LC-MS). The extracts were chromatographed alongside commercial reference standards of asiatic acid, madecassic acid, asiaticoside, and madecassoside (ChromaDex, Irvine, CA). Analysis was performed using LC-MS in negative ion mode on an LCQ Advantage ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron, San Jose, CA) with an in-line Surveyor autosampler and HPLC (Thermo Electron) coupled to a Surveyor Photodiode array detector (Thermo Electron). HPLC used an Aquasil 5 μm C18 150 × 2.1 mm column eluting with a gradient of acetonitrile in water both with 0.01% formic acid (acetonitrile 5% to 25% in 20 min, to 40% at 35 min, 60% at 40 min, 75% at 45 min and then returning to starting conditions).

2.3. Administration of GKW to Mice

Fifteen Tg2576 and 20 wild-type 20-month-old female mice were committed to this experiment. Approximately half of each genotype group was administered GKW in the drinking water at a dose of 2 mg/mL of water, with water bottles changed every other day, calculated to yield 200 mg/kg/day, a dose previously shown to improve memory in wild-type rats [3]. The GKW-treated group included 8 Tg2576 and 10 wild-type mice; the untreated group included 7 Tg2576 and 10 wild-type mice. Treatment was continued for 2 weeks, the duration of treatment in published reports showing behavioral effects in wild-type animals [3]. Open-field behavior and Morris water maze testing were performed at the end of this period.

2.4. Open-Field Testing of Mice

Mice were placed in the center of a square arena (38 × 38 × 64 cm high) constructed of white acrylonitrile butadiene styrene for two 5-minute open-field sessions on each of three consecutive days. Distance moved and velocity of each mouse were continuously tracked with a digital camera and “ANY-maze” software (ANY-Maze, Inc., Greensburg, PA). After a 5-minute epoch was recorded, the mouse was returned to the cage for 5 minutes and then retested. For each mouse, two tests were conducted on each of 3 days.

2.5. Morris Water Maze Testing of Mice

A subset of the treated animals (5 untreated wild-type, 5 GKW-treated Tg2576, and 5 untreated Tg2576) was also tested in the Morris water maze, a well established assay of hippocampal spatial memory [15]. This paradigm tests the animal ability to learn and remember the spatial location of a platform submerged 1 cm in a 109 cm circular pool of opaque water. The mice were habituated to the examination room and holding cages for two days and then received two days of “nonspatial training” before commencement of hidden platform testing. Each nonspatial training trial comprised placing the mouse on the submerged platform for 60 sec and then placing the mouse in close proximity (within 2-3 cm) to the platform and allowing it to climb onto the platform from the water. Training on the hidden platform water maze task began 24 hr after the last habituation trial. At this stage, curtains were opened to permit the mice visual access to extra maze cues in the room surrounding the maze. Hidden platform training was conducted over 16 trials on 4 consecutive days (4 trials/day). The platform remains in a fixed position throughout hidden platform training. During a given trial, the mouse is introduced into the pool at one of four randomly chosen start points (N, S, W, and E) and allowed 60 sec to find the platform. All trials were monitored by a video camera positioned above the pool and the behavior of each mouse was acquired by a computerized video tracking system (ANY-Maze software). Dependent measures acquired in each trial include the escape latency (i.e., time to find the platform, in sec), the cumulative distance (in cm) of the mouse from the platform, and swim speed (in cm/sec). No mice in this group needed to be excluded based on difficulty in swimming, in climbing onto the platform, or exhibiting abnormal swimming patterns or persistent floating.

2.6. Brain Levels of Soluble and Insoluble Aβ

Brain levels of Aβ were measured in experimental mice at the conclusion of behavioral testing described above. Tg2576 mice were sacrificed and brains rapidly harvested, divided, and frozen until analysis. Cortical tissue was then homogenized in buffered saline and protease inhibitors and ultracentrifuged to yield a “soluble” fraction, as we have reported previously [16–18]. The remaining pellet was rehomogenized and incubated in guanidine and buffer and subsequently ultracentrifuged to yield a “fibrillar” fraction. Concentrations of Aβ 1-40 and Aβ 1-42 were determined in each supernatant using commercial ELISA kits, which distinguish the two isoforms (BioSource international, Camarillo, CA). Total protein in each fraction was determined by the Bradford method.

2.7. Neurotoxicity Induced by Extracellular Aβ

SHSY5Y neuroblastoma cells were grown in DMEM/F12 medium (from Gibco) containing fetal calf serum (FCS; 10%), streptomycin sulphate (100 μg/mL), and penicillin G (1000 U/mL) in a humidified air/5% CO2 chamber at 37°C. On day 1, the cells were plated in 24-well plates (100,000 cells/well).

On day 4, cells were washed with FCS-free medium and further incubated in FCS-free DMEM/F12 containing neuroblastoma growth supplement N-2 (1%; Gibco). GKW (0–200 μg/mL) was added and incubated overnight. On day 5, cells were exposed to Aβ 25-35 (American Peptide Company) at 20 or 50 μM for 48 hrs in the presence of GKW. For this assay, fibrillar Aβ solution was freshly prepared by sonicating a solution of Aβ 25-35 in medium for 1 minute prior to addition to cell cultures. On day 7, the supernatant was harvested for LDH cell integrity assay; LDH release is a marker of cell damage [19]. Fresh medium was added and cell number assessed using CellTiter-Blue reagent (resazurin, Promega), incubating for 2 hours and reading fluorescence at 560 nm excitation and 590 nm emission.

2.8. Intracellular Aβ-Induced Neurotoxicity in MC65 Cells

MC65 cells are an established neuroblastoma cell line that conditionally express the C-terminal fragment of amyloid precursor protein (APP CTF) [20]. Following withdrawal of tetracycline from the media, the cells generate endogenous Aβ and die within 3 days. Expression of APP CTF in MC65 cells leads to the formation of intracellular Aβ aggregates. Previous studies have shown a strong correlation between these aggregates and subsequent cytotoxicity that is associated with oxidative stress [21]. MC65 cells were cultured and maintained in MEMEα supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco-BRL, Carlsbad, CA) and 1 μg/mL tetracycline (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as previously described [21, 22]. Confluent cells were trypsinized, washed with PBS, resuspended in OptiMEM without phenol red (Gibco/BRL, Carlsbad, CA), and plated at 25,000 cells/well in 48-well plates in fresh medium containing vehicle or desired concentrations of GKW, in the absence of tetracycline. Cell viability was measured at 2.75 days using the CellTiter 96 Aqueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) according to manufacturer's instructions. Experiments were carried out in triplicate wells for each condition and repeated 1-2 times.

2.9. APP CTF Aggregation in MC65 Cells

Cells were plated in culture dishes without tetracycline in the presence or absence of 100 μg/mL GKW. Cells were harvested at 2 days and lysates prepared by sonication and heating in Laemmli sample buffer. Samples were reduced then separated on tricine gels, transferred, and western blotted using mouse monoclonal antibody 6E10 that recognizes Aβ 1-17.

2.10. Aβ-Induced Nitric Oxide in Macrophages

RAW 264.7 cells were cultured in complete phenol red-free DMEM containing 50 units/mL of penicillin, 50 mg/mL of streptomycin, 44 mM sodium bicarbonate, and 10% fetal bovine serum (complete medium) at 37°C in humidified air containing 5% CO2. Cells were plated in 24-well plates (approximately 1 × 105 cells/well) and cultured for 2 days until cells reached 80% confluency. Cells were washed, treated with fresh complete media containing various concentrations of GKW for 1 hour, and then induced with LPS (100 ng/mL) or Aβ 1-42 (20 μM) for an additional 24 hours. Aβ fibril formation was induced by incubating Aβ at 37°C overnight prior to addition to cell cultures. Nitrite was determined in supernatants from treated macrophages using Griess reagent as described previously [23, 24]. Nitrite concentrations were determined using dilutions of sodium nitrite in complete medium as a standard.

2.11. Anticholinesterase Activity

Cholinesterase activity was measured by the method of Ellman et al. [25], which is based on the formation of a yellow reaction product when thiocholine is liberated from acetylthiocholine and combines with the test reagent, dithiobisnitrobenzoic acid (DTNB). Potential cholinesterase inhibitory effect of GKW was tested directly in an assay using mouse plasma cholinesterase. DTNB buffer (80 μL) was added to a 96-well plate, followed by mouse plasma (5 μL), and then test agent (5 μL), consisting of GKW solution (2.5, 25, and 250 μg/mL), neostigmine (2.5 μg/mL; positive control), or buffer (negative control) and the solution was warmed to 37°C. The substrate, acetylthiocholine, was then added and absorbance recorded at 450 nm for 5 minutes.

2.12. Glutamate-Induced Neurotoxicity

Potential protection against glutamate-induced toxicity was examined in cortical neurons obtained from neonatal Sprague-Dawley rats. On day 1, cells were plated (200,000 cells per well) in 48-well plates using neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 (2%) containing antioxidants, 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco). On day 4, the cells were treated with Ara-C (5 μM) to remove glial cells. On day 7, cells were washed with prewarmed CSF buffer (2x, 0.5 mL/well) then incubated with neurobasal medium, plus L-glutamine (2 mM) and B27 (2%) minus antioxidants, overnight. On day 8, sodium glutamate (0–1000 μM) with or without GKW (0–200 μg/mL) was added to the medium and the cells incubated overnight. On day 9, fresh medium was added and cell number evaluated using CellTiter Blue reagent (resazurin, Promega), incubating for 2 hours and reading fluorescence in a fluorimeter at 560 nm excitation and 590 nm emission.

2.13. Antioxidant Activity

Potential antioxidant effects of GKW were assessed in vitro in SH-SY5Y cells treated with hydrogen peroxide as an oxidative stressor. SHSY5Y neuroblastoma cells were grown in DMEM/F12 medium (from Gibco) containing fetal calf serum (FCS; 10%), streptomycin sulphate (100 μg/mL), and penicillin G (1000 U/mL) in a humidified air/5% CO2 chamber at 37°C. On day 1, the cells were plated in 24-well plates (100,000 cells/well). On day 4, medium was replenished with fresh medium containing NGF (10 ng/mL). After 24 hours (day 5), GKW (0, 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL) was added and the cells incubated overnight. On day 6, medium containing GKW was replaced with fresh medium containing less FCS (2%) and NGF (10 ng/mL). Cells were treated with a range of concentrations of H2O2 (0–500 μM) for 2-3 hours. Medium containing peroxide was removed and cells incubated overnight in fresh medium containing FCS (2%) and NGF (10 ng/mL). On day 7, supernatant was harvested for lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) cell integrity assay (102). Fresh medium was added and cell number evaluated using CellTiter Blue reagent (resazurin, Promega), incubating for 2 hours and reading fluorescence at 560 nm excitation and 590 nm emission.

3. Results and Discussion

The water extractable compounds (GKW) represented approximately 10% of the dry weight of CA herb. There was no difference in water consumption between control animals and animals receiving water containing GKW.

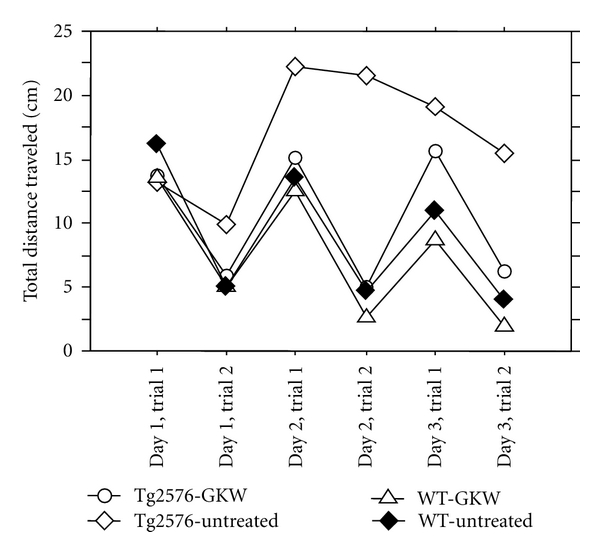

Open-field testing (Figure 1) showed that GKW treatment caused an improvement in behavioral abnormalities seen in Tg2576 mice. Wild-type mice, both GKW treated and untreated, were less active on the second trial of each day, presumably due to habituation. Untreated Tg2576 mice, in contrast, failed to habituate to the surroundings. However, GKW-treated Tg2576 mice explored in a manner similar to wild-type mice, with their data overlapping the two wild-type groups (P = 0.02 for difference between untreated and GKW-treated Tg2576 mice by ANOVA). “Normalization” of open-field behavior in Tg2576 mice has also been reported with an intervention that suppresses soluble Aβ levels [12].

Figure 1.

Open-field assay: effect of GKW on total distance travelled. Wild-type mice, both treated (triangle) and untreated (filled diamond), are less active on the second trial of each day, presumably due to habituation. Untreated Tg2576 mice (open diamond), in contrast, fail to habituate to the surroundings. GKW-treated Tg2576 mice (circles) explore in a manner similar to wild-type mice, with their data overlapping the two wild-type groups. From statistical analysis (ANOVA), P = 0.02 for difference between untreated (n = 7) and GKW-treated (n = 8) Tg2576 mice; error bars omitted for clarity.

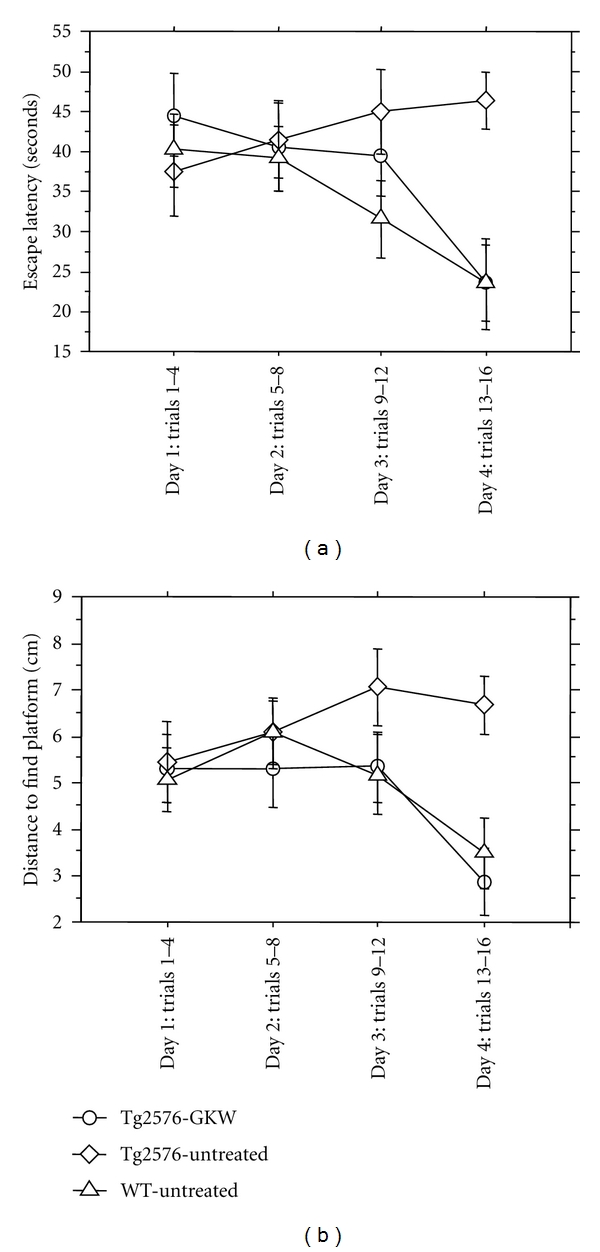

In the Morris water maze paradigm (Figure 2), GKW treatment improved the impaired learning ability evident in Tg2576 mice. Wild-type animals exhibit a “learning curve” requiring less time and less distance to find the hidden platform with repeated trials, while untreated Tg2576 mice require equivalent time and distance despite repeated exposures. In contrast, the GKW-treated Tg2576 mice learn in a manner similar to the wild-type animals, with latency and distance traveled to find the platform declining with repeated exposures. On day 4, time to find the platform was significantly greater for untreated Tg2576 mice than for wild-type (P = 0.002) or GKW-treated Tg2576 mice (P = 0.004). Distance traveled to find the platform was also significantly greater on day 4 for untreated Tg2576 mice compared to wild-type (P = 0.006) or GKW-treated Tg2576 mice (P = 0.003). There was no significant difference between groups in the “visible platform” control for sensorimotor function (data not shown).

Figure 2.

GKW effects in the Morris water maze. Mean ± SEM of (a) escape latency and (b) distance traveled to find platform is shown for each day of testing. Wild-type animals exhibit a “learning curve” requiring less time and less distance to find the hidden platform with repeated trials, while untreated Tg2576 mice require equivalent time and distance despite repeated exposures. In contrast, the GKW-treated mice learn in a manner similar to the wild-type animals, with latency and distance traveled to find the platform declining with repeated exposures. On day 4, time to find the platform was significantly greater for untreated Tg2576 mice than for wild-type (P = 0.002) or GKW-treated Tg2576 mice (P = 0.004). Distance traveled to find the platform was also significantly greater on day 4 for untreated Tg2576 mice compared to wild-type (P = 0.006) or GKW-treated Tg2576 mice (P = 0.003).

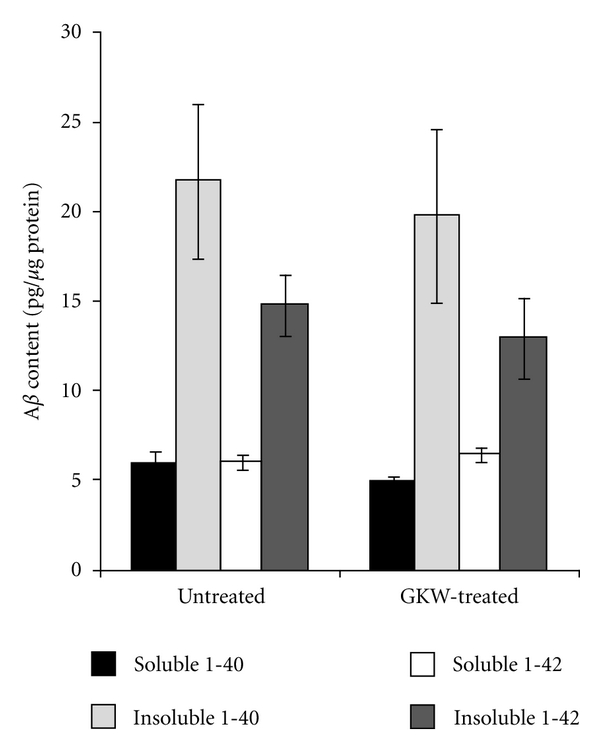

Since treatment with GKW ameliorated a spatial memory impairment in Tg2576 mice, which is specifically associated with the appearance of Aβ plaques, without producing any change in wild-type mouse memory, it would appear that the observed effect of GKW is specific to Aβ. However, Figure 3 shows that there were no significant differences between levels of any of the forms of Aβ in treated and untreated Tg2576 mice. This is in contrast to results obtained in PSAPP mice, a model for Alzheimer's disease (AD) where mice express both amyloid precursor protein and presenilin 1 mutations, in the long term (8 months). In these mice, administration of CA extract displayed in vitro antioxidant effects and also reduced beta amyloid plaque burden [26]. The PSAPP mice develop amyloid plaque pathology at an earlier age than Tg2576 [27], permitting more rapid completion of antiamyloid experiments. However, loss of the age- and region-dependence of pathology diminishes the fidelity of this strain to some extent. Since GKW treatment attenuated the neurologic consequences of abnormal Aβ deposition in Tg 2576 mice without changing Aβ levels per se, the ability of GKW to modulate the toxic effects of Aβ were pursued in vitro, with an emphasis on mechanisms which are either independent of or “downstream” from Aβ.

Figure 3.

Soluble and insoluble Aβ in cortical tissue from treated and untreated mice. Mean values ± SEM are shown. Treated and untreated Tg2576 mice did not differ significantly in levels of any of the measured isoforms of Aβ.

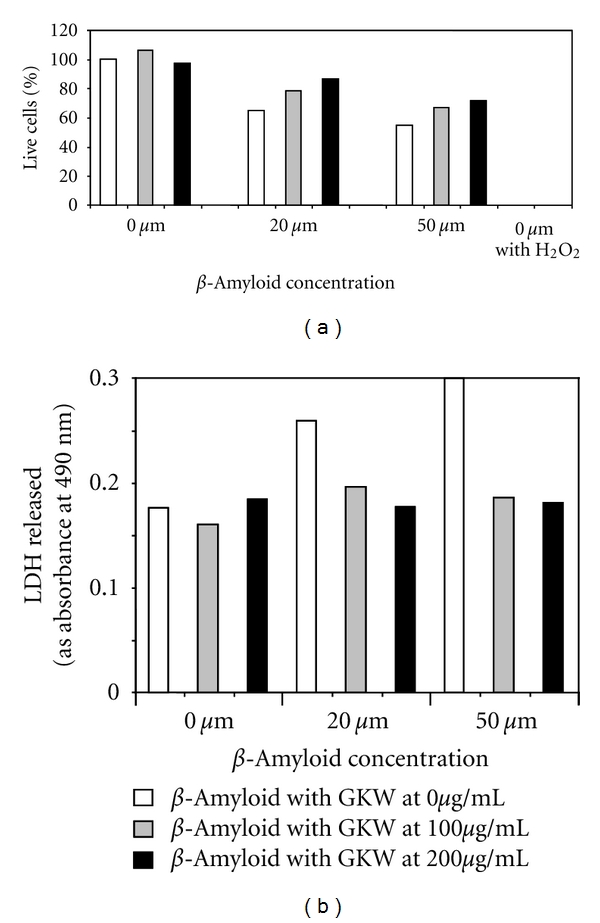

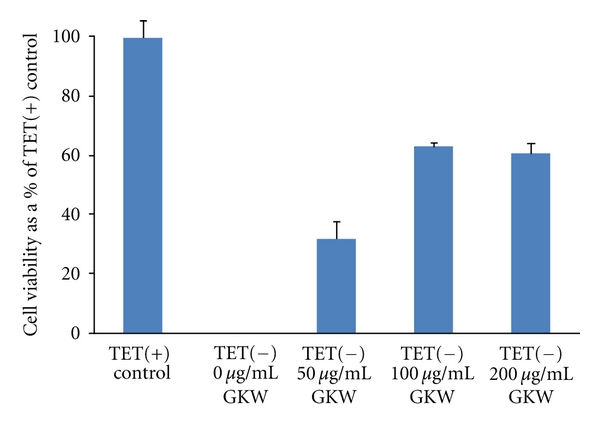

In preliminary experiments, GKW showed a moderate protective effect against toxicity due to exogenously added Aβ in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells in vitro (Figure 4(a)). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release from these cells, which is inversely related to cell viability, was reduced in the presence of GKW (Figure 4(b)). The effect of GKW on toxicity due to endogenously generated Aβ was investigated in MC65 human neuroblastoma cells. GKW added to the cell culture medium prevented MC65 cell death following tetracycline withdrawal, in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5). Evidence from Western blots indicated that GKW may prevent the aggregation of Aβ in these cells. In a related study (data not shown), GKW inhibited Aβ-induced nitric oxide (NO) production in the RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line. Interestingly, GKW inhibited NO production induced by Aβ but did not influence LPS-induced NO levels in these cells. Taken together, these data indicated that components in GKW are able to modulate the toxic effects of Aβ.

Figure 4.

(a) GKW at 100 and 200 μg/mL shows a modest protective effect on SH-SY5Y cells from Aβ toxicity (beta amyloid 25–35) in vitro. The % of live cells is decreased on treatment with Aβ, an effect which is attenuated by GKW. Hydrogen peroxide 500 μM is used as a 0 cell viability control. (b) GKW at 100 and 200 μg/mL protects SH-SY5Y cells from Aβ toxicity (beta amyloid 25–35) in vitro—LDH release. The amount of LDH (lactate dehydrogenase) released is increased on treatment with Aβ, an effect which is attenuated by GKW. LDH release is a marker of cell damage.

Figure 5.

Effect of GKW on survival of MC65 cells following tetracycline withdrawal. Cell viability is expressed as a % of the cell growth obtained in control cultures containing tetracycline, TET(+). On withdrawal of tetracycline from the media, TET(−), the cells generate endogenous Aβ and die within 3 days. In the absence of GKW, cell survival in TET(−) cultures is zero. GKW dose-dependently protects MC65 cells from cell death in TET(−) cultures (P < 0.01 at 50, 100, and 200 μg/mL compared to 0 μg/mL GKW; Student's t-test). Mean values of cell viability ± SD are shown.

Other potential mechanisms by which GKW may have improved cognitive function in the Tg2576 mice were also investigated but yielded negative results. No direct inhibitory effect of GKW (2.5 to 250 μg/mL) on cholinesterase activity in vitro was observed, whereas robust inhibition was observed using the positive control neostigmine. Effects of GKW on glutamate toxicity to rat cortical neurons were investigated. GKW (100 or 200 μg/mL) was not directly toxic to rat cortical neurons nor did it protect the cells from toxicity induced by 250 and 1000 μM glutamate (cell viability 30% and 25% of control, resp.). To examine potential antioxidant effects of GKW, SHSY5Y neuronal cells were exposed to H2O2, which showed dose-dependent toxicity to SH-SY5Y cells over the range 125–500 μM. GKW (50–200 μg/mL), while not toxic to the cells, did not protect against toxicity at any of the peroxide concentrations tested. Thus, GKW does not appear to possess antioxidant effects.

Five drugs are currently FDA-approved for the symptomatic treatment of AD, targeting mechanisms of unclear relationship to the primary neurodegenerative process. The first four drugs (tacrine, donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine) are acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, which act by augmenting cholinergic neurotransmission [28]. Each of these drugs has shown improved cognitive outcomes in treated AD patients compared to placebo-treated subjects, and the efficacy across drugs makes the case that cholinesterase inhibition is a viable treatment strategy for AD [28]. The fifth and most recent antidementia drug to receive FDA approval is memantine. Memantine is a noncholinergic drug, acting instead at the NMDA class of glutamate receptor. In addition to showing clinical efficacy in human subjects with AD [29, 30], memantine has also been shown to improve cognition in murine models of cerebral amyloidosis. NMDA antagonism should therefore be considered among the possible mechanisms of action of treatments producing cognitive improvement in murine models of AD. Our in vitro experiments showed no evidence that CA acts by way of these established therapeutic targets since there was no effect on cholinesterase activity or glutamate neurotoxicity.

In addition to the established therapies just described, strategies aimed at preventing the accumulation of, or promoting the clearance of, Aβ are under study. Inhibitors of amyloid synthesis and immunization against Aβ have diminished brain pathology and yielded cognitive and behavioral improvements in murine models of AD. Although amyloid synthesis inhibitors such as Lilly semagacestat have yielded negative clinical results [31], antiamyloid immunotherapy (bapineuzumab) remains under development with some promising initial results [32]. “Antiamyloid” strategies, therefore, represent another potential mechanism of cognition-enhancing therapies in AD. Our results do not show an effect of CA on Aβ levels per se but suggest that CA may protect neurons from Aβ-induced neurotoxicity without actually changing brain levels of Aβ. Most current clinical trials are focused on suppression of Aβ levels, thus the neuroprotectant effect of CA described here represents a novel mechanism, potentially complementary to the drugs in development.

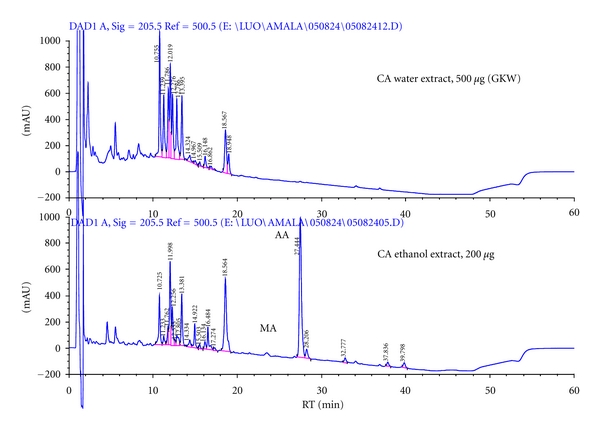

CA may also be a source of a novel chemical class for the treatment of AD. HPLC analysis of GKW revealed a complex mixture of substances (Figure 6). This did not include asiatic acid or madecassic acid, well-known triterpene components of CA [33, 34], which were, however, extractable from the same plant material using ethanol (Figure 6). The absence of asiatic acid in GKW is notable since asiatic acid has been previously associated with neuroprotective and neurotropic effects [35–38]. However, an aqueous extract lacking asiatic acid produced robust behavioral effects in this study. Table 1 lists the spectral characteristics of the major peaks found in GKW using LC-UV and LC-MS. UV spectra with maxima over 300 nm are indicative of a highly conjugated system, characteristic of flavonoids. CA is reported to be a rich source of quercetin [39]. Flavonoids isolated to date in CA include 3-glucosylkaempferol, 3-glucosylquercetin and diosmin [40, 41]. The molecular weights listed in Table 1 did not correspond to any of these 3 compounds, nor any other compounds isolated hitherto from CA (online chemical database, SciFinder). These findings imply the presence of potentially novel neuroactive ingredients in GKW which are yet to be fully characterized.

Figure 6.

HPLC comparison of CA water and ethanol extracts made from the same batch of plant material. Asiatic acid (AA) and madecassic acid (MA) are detected in the ethanolic extract, but not in the water extract (GKW). The water extract GKW contains mostly very polar compounds as shown by their earlier elution than the triterpenes AA and MA. HPLC was conducted on an Aquasil 150 mm × 2.1 mm C18 column with acetonitrile:water gradient with 0.1% acetic acid. Acetonitrile concentration 10% at 0 min, 50% at 25 min, 90% at 40 min, then returning to starting conditions, detector wavelength 205 nm. AA and MA were identified by comparison of retention times to those of commercial standards.

Table 1.

Molecular weight and UV data obtained for GKW components using LC-MS and LC-UV. Reversed phase gradient HPLC chromatography with UV and negative ion mass spectral detection was performed as described in Section 2.

| Retention time | Most abundant ions (m/z); (Mol Wt−1) | UV λ max (nm) | Possible structure, based on flavonoid handbook [46] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12.33 | 399, 353 | 215, 325 | Prenylated flavone |

| 16.57 | 531 | 215, 265, 310 | Malonyl, butyryl, or diacetyl flavone glycoside |

| 21.05 | 477 | 205, 255, 355 | Glycosyl or glucuronyl methylated flavones |

| 22.64 | 561, 515 | 215, 325 | Diglycosyl flavonoid or a catechin |

| 25.21 | 601 | 215, 325 | No matches found |

| 33.49 | 577 | 220, 295, 320 | Diglycosyl flavonoid or a proanthocyanidin |

Compared to the wealth of animal data described earlier, there have been fewer studies on cognitive effects of CA in humans. In one study, 30 mentally retarded children aged 7–18 years showed improvement in their general abilities after receiving 500 mg daily of dried CA herb for 3 months [42]. A more recent study [43] showed that an extract of CA (250–750 mg daily for 2 months) improved cognitive performance in healthy, elderly volunteers. In a placebo-controlled study, administration of CA herb (0.5 g/kg body weight) to healthy, middle-aged volunteers for 2 months resulted in improvements in several tests of cognitive function [44]. A study in elderly subjects with mild cognitive impairment found improvements in their cognitive test results, including the mini mental state examination, following administration of 500 mg dried CA twice a day for a 6-month period [45].

The traditional use of CA as an enhancer of cognitive function is therefore well supported by in vitro, in vivo, and small-scale human studies conducted so far. The ultimate goal of these studies is to develop evidence for the clinical use of CA, or compounds derived from CA, in the treatment or prevention of AD. The combination of data from in vitro and animal studies in the present work supports the impression that CA has the potential for clinical benefit in AD by way of a novel mechanism of action. Well-designed, controlled clinical trials of CA in AD and other forms of cognitive impairment are clearly warranted. The characterization of the active components of CA and elucidation of their mechanism of action would support these clinical studies.

4. Conclusions

A water extract of CA (GKW) attenuated Aβ-associated behavioral abnormalities in the Tg2576 mouse, a murine model of AD. In vitro, GKW protected SH-SY5Y cells and MC65 human neuroblastoma cells from toxicity induced by exogenously added and endogenously generated Aβ, respectively. GKW did not show anticholinesterase activity or protect neurons from oxidative damage and glutamate toxicity, mechanisms of current AD therapies. The combination of data from in vitro and animal studies in the present work supports the CA potential for conferring clinical benefit in AD, possibly by way of a novel mechanism of action. GKW does not contain asiatic acid, a known CA neuroprotective triterpene, but is rich in phenolic compounds. CA may therefore contain novel active compounds of relevance to the treatment of AD.

Conflict of Interests

At the time of conducting this research, A. Soumyanath was an employee of Oregon's Wild Harvest, the supplier of Centella asiatica used in this study. This potential conflict of interests has been reviewed and managed by OHSU.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants awarded to A. Soumyanath from NIH P50 AT00066, the Oregon Alzheimer's Disease Center (NIA-AG08017), and the Oregon Partnership for Alzheimer's Research and by a Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review grant awarded to J. Quinn. LC-UV and LC-MS work was supported by the Bio-Analytical Shared Resource/Pharmacokinetics Core in the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology at Oregon Health & Science University.

References

- 1.Kapoor L. Handbook of Ayurvedic Medicinal Plants. Boca Raton, Fla, USA: CRC Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newall CA, Anderson L, Phillipson JD. Herbal Medicines: A Guide for Healthcare Professionals. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar MHV, Gupta YK. Effect of different extracts of Centella asiatica on cognition and markers of oxidative stress in rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2002;79(2):253–260. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00394-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veerendra Kumar MH, Gupta YK. Effect of Centella asiatica on cognition and oxidative stress in an intracerebroventricular streptozotocin model of Alzheimer’s disease in rats. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 2003;30(5-6):336–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2003.03842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta YK, Veerendra Kumar MH, Srivastava AK. Effect of Centella asiatica on pentylenetetrazole-induced kindling, cognition and oxidative stress in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2003;74(3):579–585. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)01044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao SB, Chetana M, Devi PU. Centella asiatica treatment during postnatal period enhances learning and memory in mice. Physiology & Behavior. 2005;86(4):449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gadahad MR, Rao M, Rao G. Enhancement of hippocampal CA3 neuronal dendritic arborization by Centella asiatica (Linn) fresh leaf extract treatment in adult rats. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association. 2008;71(1):6–13. doi: 10.1016/s1726-4901(08)70066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohandas Rao KG, Muddanna Rao S, Gurumadhva Rao S. Centella asiatica (L.) leaf extract treatment during the growth spurt period enhances hippocampal CA3 neuronal dendritic arborization in rats. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2006;3(3):349–357. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsiao K. Transgenic mice expressing Alzheimer amyloid precursor proteins. Experimental Gerontology. 1998;33(7-8):883–889. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(98)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, et al. Correlative memory deficits, Aβ elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274(5284):99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calon F, Lim GP, Yang F, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid protects from dendritic pathology in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Neuron. 2004;43(5):633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim GP, Yang F, Chu T, et al. Ibuprofen effects on Alzheimer pathology and open field activity in APPsw transgenic mice. Neurobiology of Aging. 2001;22(6):983–991. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stackman RW, Eckenstein F, Frei B, Kulhanek D, Nowlin J, Quinn JF. Prevention of age-related spatial memory deficits in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease by chronic Ginkgo biloba treatment. Experimental Neurology. 2003;184(1):510–520. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00399-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner H. Plant Drug Analysis: A Thin Layer Chromatography Atlas. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris RG, Garrud P, Rawlins JN, O’Keefe J. Place navigation impaired in rats with hippocampal lesions. Nature. 1982;297(5868):681–683. doi: 10.1038/297681a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quinn J, Kulhanek D, Nowlin J, et al. Chronic melatonin therapy fails to alter amyloid burden or oxidative damage in old Tg2576 mice: implications for clinical trials. Brain Research. 2005;1037(1-2):209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stackman RW, Eckenstein F, Frei B, Kulhanek D, Nowlin J, Quinn JF. Prevention of age-related spatial memory deficits in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease by chronic Ginkgo biloba treatment. Experimental Neurology. 2003;184(1):510–520. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00399-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quinn JF, Bussiere JR, Hammond RS, et al. Chronic dietary α-lipoic acid reduces deficits in hippocampal memory of aged Tg2576 mice. Neurobiology of Aging. 2007;28(2):213–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson A. Cytotoxicity and viability assays. In: Freshney R, editor. Animal Cell Culture: A Practical Approach. Oxford, UK: IRL Press; 1992. pp. 263–303. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sopher BL, Fukuchi KI, Kavanagh TJ, Furlong CE, Martin GM. Neurodegenerative mechanisms in Alzheimer disease: a role for oxidative damage in amyloid β protein precursor-mediated cell death. Molecular and Chemical Neuropathology. 1996;29(2-3):153–168. doi: 10.1007/BF02814999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woltjer RL, McMahan W, Milatovic D, et al. Effects of chemical chaperones on oxidative stress and detergent-insoluble species formation following conditional expression of amyloid precursor protein carboxy-terminal fragment. Neurobiology of Disease. 2007;25(2):427–437. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woltjer RL, Maezawa I, Ou JJ, Montine KS, Montine TJ. Advanced glycation endproduct precursor alters intracellular amyloid-β/AβPP carboxy-terminal fragment aggregation and cytotoxicity. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2003;5(6):467–476. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wadsworth TL, McDonald TL, Koop DR. Effects of Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) and quercetin on lipopolysaccharide-induced signaling pathways involved in the release of tumor necrosis factor-α . Biochemical Pharmacology. 2001;62(7):963–974. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00734-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wadsworth TL, Koop DR. Effects of the wine polyphenolics quercetin and resveratrol on pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1999;57(8):941–949. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, Jr., Featherstone RM. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1961;7(2):88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dhanasekaran M, Holcomb LA, Hitt AR, et al. Centella asiatica extract selectively decreases amyloid β levels in hippocampus of Alzheimer’s disease animal model. Phytotherapy Research. 2009;23(1):14–19. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holcomb L, Gordon MN, Mcgowan E, et al. Accelerated Alzheimer-type phenotype in transgenic mice carrying both mutant amyloid precursor protein and presenilin 1 transgenes. Nature Medicine. 1998;4(1):97–100. doi: 10.1038/nm0198-097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tariot PN, Federoff HJ. Current treatment for Alzheimer disease and future prospects. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2003;17(4):S105–S113. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200307004-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tariot PN, Farlow MR, Grossberg GT, Graham SM, McDonald S, Gergel I. Memantine treatment in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease already receiving donepezil: a randomized controlled trial. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(3):317–324. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reisberg B, Doody R, Stöffler A, Schmitt F, Ferris S, Möbius HJ. Memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348(14):1333–1341. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.A study in semagacestat for Alzheimer's patients (Identity XT) http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01035138.

- 32.Panza F, Frisardi V, Imbimbo BP, et al. Bapineuzumab: anti-β-amyloid monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Immunotherapy. 2010;2(6):767–782. doi: 10.2217/imt.10.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brinkhaus B, Lindner M, Hentschel C, et al. Centella asiatica in traditional and modern phytomedicine—a pharmacological and clinical profile—part I: botany chemistry, preparations. Perfusion. 1998;11(11):466–474. [Google Scholar]

- 34.James JT, Dubery IA. Pentacyclic triterpenoids from the medicinal herb, Centella asiatica (L.) Urban. Molecules. 2009;14(10):3922–3941. doi: 10.3390/molecules14103922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soumyanath A, Zhong YP, Gold SA, et al. Centella asiatica accelerates nerve regeneration upon oral administration and contains multiple active fractions increasing neurite elongation in-vitro. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2005;57(9):1221–1229. doi: 10.1211/jpp.57.9.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee MK, Kim SR, Sung SH, et al. Asiatic acid derivatives protect cultured cortical neurons from glutamate-induced excitotoxicity. Research Communications in Molecular Pathology and Pharmacology. 2000;108(1-2):75–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jew S-S, Yoo C-H, Lim D-Y, et al. Structure-activity relationship study of asiatic acid derivatives against β amyloid (Aβ)-induced neurotoxicity. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2000;10(2):119–121. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00658-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mook-Jung I, Shin JE, Yun HS, et al. Protective effects of asiaticoside derivatives against β-amyloid neurotoxicity. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1999;58(3):417–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bajpai M, Pande A, Tewari SK, Prakash D. Phenolic contents and antioxidant activity of some food and medicinal plants. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 2005;56(4):287–291. doi: 10.1080/09637480500146606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allegra C. Comparative capillaroscopic study of some bioflavonoids and total triterpene fraction of Centella asiatica in venous insufficiency. Clinica Terapeutica. 1984;110(6):555–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prum N, Illel B, Raynaud J. The flavonoid glycosides from Centella asiatica L. (Umbelliferae) Pharmazie. 1983;38(6):p. 423. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Appa Rao MVR, Srinivasan K, Koteswara Rao T. The effect of Mandookaparni (Centella asiatica) on the general mental ability (medhya) of mentally retarded children. Journal of Research in Indian Medicine. 1973;8:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wattanathorn J, Mator L, Muchimapura S, et al. Positive modulation of cognition and mood in the healthy elderly volunteer following the administration of Centella asiatica. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;116(2):325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dev RDO, Mohamed S, Hambali Z, Samah BA. Comparison on cognitive effects of Centella asiatica in healthy middle age female and male volunteers. European Journal of Scientific Research. 2009;31(4):553–565. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tiwari S, Singh S, Patwardhan K, Gehlot S, Gambhir IS. Effect of Centella asiatica on mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and other common age-related clinical problems. Digest Journal of Nanomaterials and Biostructures. 2008;3(4):215–220. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harborne JB, Baxter H. The Handbook of Natural Flavonoids. Vol 1 and 2. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]