Abstract

The generation and analysis of mutants in zebrafish has been instrumental in defining the genetic regulation of vertebrate development, physiology, and disease. However, identifying the genetic changes that underlie mutant phenotypes remains a significant bottleneck in the analysis of mutants. Whole-genome sequencing has recently emerged as a fast and efficient approach for identifying mutations in nonvertebrate model organisms. However, this approach has not been applied to zebrafish due to the complicating factors of having a large genome and lack of fully inbred lines. Here we provide a method for efficiently mapping and detecting mutations in zebrafish using these new parallel sequencing technologies. This method utilizes an extensive reference SNP database to define regions of homozygosity-by-descent by low coverage, whole-genome sequencing of pooled DNA from only a limited number of mutant F2 fish. With this approach we mapped each of the five different zebrafish mutants we sequenced and identified likely causative nonsense mutations in two and candidate mutations in the remainder. Furthermore, we provide evidence that one of the identified mutations, a nonsense mutation in bmp1a, underlies the welded mutant phenotype.

A major strength of the zebrafish (Danio rerio) model is the feasibility of performing large-scale genetic screens as a means to isolate mutants to study gene function. Such forward genetic screens have led to the identification of a large collection of mutants defective in a variety of biological processes. The standard approach for identifying the responsible mutation underlying a mutant phenotype is to perform bulked segregant analysis with simple sequence length polymorphisms (SSLPs) (Geisler et al. 2007), followed by fine mapping using individual fish to define the region in which the mutation lies. Candidate genes within the mapped interval are then screened for the presence of mutations, typically by sequencing cDNA or genomic DNA. This approach is time and labor intensive, requiring large numbers of mutant fish and often years to successfully clone a mutant. To date this is a major limitation in zebrafish research, and large numbers of mutants have not yet been mapped or cloned.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has the potential to expedite the process of mutation detection in zebrafish. In Caenorhabditis elegans and Arabidopsis thaliana, multiple studies have shown that, by pooling from 10 to 500 recombinant progeny and sequencing to a relatively high depth, a linked region between 0.5 and 5 Mb in size as well as the responsible mutation can be identified (Schneeberger et al. 2009; Cuperus et al. 2010; Doitsidou et al. 2010; Zuryn et al. 2010; Austin et al. 2011; Uchida et al. 2011). Similarly, WGS of individual mutant mice (Arnold et al. 2011) or human patients with genetic disorders (Sobreira et al. 2010) has led to the identification of causative mutations. However, in the case of mice and humans, prior knowledge of linkage was necessary to determine which of the many sequence variants identified in the genome were associated with the phenotype.

Mapping mutants by performing WGS has not yet been applied to zebrafish. One prohibitive factor has been the high cost of sequencing an entire zebrafish genome (∼1.5 Gb, compared to 100 Mb for C. elegans and 120 Mb for A. thaliana). However, new sequencing platforms have increased the throughput of sequencing and reduced its cost, now making it practical to obtain low-coverage sequence data of an entire zebrafish genome. A second prohibitive factor for applying WGS for mutation detection in zebrafish is the high level of inter- and intrastrain variation (Stickney et al. 2002; Guryev et al. 2006; Bradley et al. 2007; Coe et al. 2009) and the absence of a well-annotated catalog of natural variation; consequently, this makes it more difficult to determine whether a novel homozygous variant is a causative mutation or a low-frequency single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). This contrasts with the inbred organisms for which WGS has been successfully applied (Schneeberger et al. 2009; Cuperus et al. 2010; Doitsidou et al. 2010; Zuryn et al. 2010; Austin et al. 2011; Uchida et al. 2011). Here, we describe the establishment of an extensive zebrafish SNP database. Using this database in combination with low-coverage (∼3×) WGS, we developed a rapid and inexpensive method to efficiently map, and frequently clone, recessive mutations in zebrafish. Furthermore, the methodology described here can be used to identify genetic loci in other model organisms with larger and highly polymorphic genomes that have annotated genomes, such as rats, mice, dogs, chickens, and other fish species.

Materials and Methods

Zebrafish husbandry and strains

Zebrafish were raised and maintained as described (Nüsslein-Volhard and Dahm 2002). Mutants were identified in the 2004 ZF-MODELS screen performed at the Max-Planck Institute for Developmental Biology (MPI-EB) in Tübingen, Germany. Mutant and wild-type strains were obtained from stocks at Children’s Hospital, Boston (TüB, WIKB, AB, and TLF) and at the MPI-EB (TüG and WIKG). The minamoto (motot31533), welded (wddt31169), hollow (hlwt3373), fruehrentner (frntt31786), and schrumpfkopf (sumpt3625) mutants were generated in the Tü background. For mapping, the majority of mutants were outcrossed to the WIK line, except for sump, which was crossed to TLF. F2 crosses were screened for the phenotype and identified mutants and siblings were frozen.

Linkage analysis

Linkage was assessed by analysis of microsatellites (SSLPs) and SNP markers on genomic DNA from single fish using standard PCR amplification and, in the case of SNPs, analysis by dideoxy capillary sequencing.

Morpholino injections

A morpholino directed against the translation initiation site of bmp1a (MO1) (Jasuja et al. 2006) was injected at a concentration of 0.3 mM into one-cell stage Tü embryos. The phenotype was assessed at 3 days postfertilization (dpf).

Genomic DNA library construction and Illumina sequencing

For each mutant or parental strain, genomic DNA from 20 adult fish was pooled (150–250 ng from each fish—also easily obtainable from larvae), and 3–5 µg was sheared to an average size of 200 bp, using Adaptive Focused Acoustics following the manufacturer’s protocol (Covaris). For three samples (wdd, sump, and frnt), the shearing step was omitted, since the genomic DNA appeared degraded, with most fragments being <250 bp in size as assessed by electrophoresis on a 4% agarose gel. To construct DNA libraries, the DNA fragments were blunt-ended, 5′ phosphorylated, A-tailed, and ligated to adaptors as previously described (Bowen et al. 2011), with the exception that adaptors did not have a 3-bp barcode sequence, and the volume of AMPure XP beads used for purification was 1.4× rather than 3.0×. Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) was then used to amplify 12 µl (30%) of each library, in a total of four 50-µl PCR reactions, using the “postcapture” primers described in Bowen et al. (2011). Eight cycles of PCR were used for wdd and six cycles for all other samples. Each amplified library was sequenced on one lane of an Illumina HiSeq2000, using 100-bp single-end sequencing. Since the number of reads obtained for frnt, TüG, WIKG, and sump was lower than expected, one lane of GAII 100-bp single-end sequencing was also performed for each of these samples.

Illumina data analysis

Illumina sequence reads were aligned to the reference genome (version Zv9/danRer7), using Novoalign software (http://www.novocraft.com/main/index.php) with default settings and including 3′-adaptor trimming. PCR duplicates were removed using the MarkDuplicates command in Picard (http://picard.sourceforge.net/). Multisample variant calling was performed for each chromosome on all samples simultaneously, using SAMtools and BCFtools. The SNPs were then filtered using the GATK VariantFiltrationWalker to exclude the following variants: (1) SNPs lying in low-complexity sequences or interspersed repeats, classified by RepeatMasker; (2) SNPs lying within 10 bp of an indel; (3) SNPs lying in a cluster of ≥3 SNPs per 10 bp; (3) SNPs with a quality score <30; (4) SNPs with a root-mean-square mapping quality of covering reads <40; and (5) SNPs with a total read depth <15 or >120. A perl script was used to exclude variants seen in <3 reads, variants not seen in both the forward and the reverse direction, variants with a tail bias <0.05, and variants that were not biallelic. Only the 7.6 million SNPs that passed these filtration steps were used for downstream analyses; of these, only a small percentage (0.25%, 18,978 SNPs) were found solely in one mutant and may represent ENU-induced variation. A perl script was written to classify the genotype of each mutant or reference strain at each of the 7.6 million “pass filter” SNP sites. Genotypes were classified as heterogeneous or homogeneous on the basis of the “BCFtools phred scaled genotype likelihood score.” Sites covered by <2 reads were considered uninformative.

To determine the physical size of the 20-cM windows used to calculate the mapping score, the MGH mapping panel was downloaded from ZFIN (http://zfin.org/zf_info/downloads.html#marker). A script was written to obtain the Zv9 genomic coordinate of each marker from Ensembl (http://useast.ensembl.org/index.html). A genomic coordinate could be obtained for 2100 of the 3845 markers. Seventy markers mapped to more than one location and were excluded from the analysis. In addition, a BLAST search was performed to find the coordinates of some markers that did not have genomic coordinates listed in Ensembl. These markers were then used to approximate the genomic coordinate of sliding 20-cM windows throughout the genome, with a new window starting every 0.25 cM.

Annovar (http://www.openbioinformatics.org/annovar/) was used to classify variants as noncoding, synonymous, or nonsynonymous and to determine whether variants were listed in the publically available SNP database, downloaded from Ensembl (http://useast.ensembl.org/info/data/ftp/index.html). To identify variants present in only one read (which would not have been identified using SAMtools/BCFtools multisample variant calling), the SAMtools mpileup command was performed on all mutants and reference strains, for all coding exons, and a perl script was used to select variants unique to each mutant. All perl scripts, as well as aligned sequence files for each wild-type strain, are available online at http://www.fishyskeleton.com.

Results

Sequencing libraries generated from pooled DNA

We performed WGS on five previously uncharacterized mutants isolated in an ENU mutagenesis screen for adult phenotypes (ZF-MODELS; Tübingen, Germany, 2004). These recessive mutants, generated in the Tü background, were outcrossed to a polymorphic mapping strain (WIK or TLF) (Supporting Information, Figure S1); progeny from F1 intercrosses were phenotyped and frozen for analysis. We pooled DNA from 20 affected F2 fish from each mutant, mixing, when possible, individuals from several independent F1 intercrosses. The F2 fish used often stemmed from either one or two parental (P0) crosses for a particular mutant, thus limiting the total genomic variation within a pool. Whole-genome sequencing was performed on genomic DNA libraries constructed from each mutant pool, resulting in between 60 and 83 million 100-bp reads per library (Table 1). We obtained between 2.6× and 4.1× coverage of the genome per mutant, after excluding 2–9% of the reads that were potential PCR duplicates (reads with identical 5′-end coordinates) and ∼25% of reads that failed to map to unique locations in the reference genome (Zv9).

Table 1 . Characteristics of linked intervals identified by whole-genome sequencing.

| Zebrafish mutanta | moto | wdd | hlw | frnt | sump |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-genome sequencing | |||||

| No. reads (106) | 61 | 81 | 60 | 79 | 83 |

| Genome coverage | 2.6× | 2.7× | 2.8× | 3.9× | 4.1× |

| Size of the linked intervalb | |||||

| Region of reduced heterogeneityc | |||||

| Physical size (Mb) | 35 | 4 | 26 | 46 | 19 |

| Genetic size (cM) | <25 | <30 | <25 | <18 | <18 |

| Region of homogeneityd | |||||

| Physical size (Mb) | 19 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 8 |

| Genetic size (cM) | <14 | <30 | <4 | <3 | <11 |

| Coding sequence coverage in linked intervale | |||||

| ≥1 read | 93% | 92% | 87% | 95% | 88% |

| ≥2 reads | 83% | 77% | 76% | 92% | 85% |

| Homogeneous SNPs in linked intervalf | |||||

| Total | 7640 | 225 | 1071 | 7783 | 9518 |

| Not in dbSNPg | 5984 | 223 | 1023 | 6431 | 9110 |

| Noncoding | 5663 | 207 | 997 | 6303 | 8687 |

| Synonymous | 229 | 12 | 17 | 89 | 287 |

| Nonsynonymous | 92 | 4 | 9 | 39 | 136 |

| Uniqueh | |||||

| Noncoding | 38 | 12 | 21 | 79 | 106 |

| Synonymous | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Nonsynonymous | 2 (63)i | 1 (119) | 0 (22) | 0 (4) | 0 (7) |

minamoto (motot31533), welded (wddt31169), hollow (hlwt3373), fruehrentner (frntt31786), and schrumpfkopf (sumpt3625).

Intervals identified by a high mapping score; linkage was confirmed by analysis of SSLP or SNP markers.

Region with a reduction in heterogeneity of at least 30% compared to the genome-wide average.

Defined as a region with a >90% reduction in heterogeneity compared to the genome-wide average.

Coding sequence of RefSeq and Ensembl genes.

Detected homogeneous variants covered by at least two sequencing reads.

Homogeneous variants not present in the publicly available SNP database (dbSNP) downloaded from Ensemble.

Homogeneous variants not present in the reference strain database established in this study.

The number of unique nonsynonymous mutations covered by only one sequencing read.

We also sequenced the genomes of four routinely used wild-type strains to establish a database of existing SNP variation. This information enabled us to predict the parental origin of SNP alleles in our mutant pools. Tü and WIK strains are commonly used in laboratories around the world. To assess the diversity among parental strains, we generated WGS from lines maintained at Children’s Hospital Boston (TüB and WIKB) and the Max Planck Institute in Tübingen, Germany (TüG and WIKG). DNA libraries, constructed from pooled DNA from 20 fish for each of the TüB, WIKB, TüG, WIKG, TLF, and AB lines, were sequenced and 3.8× to 5.1× average genome coverage was obtained (Table S1).

Establishment of a reference SNP database

With low-coverage sequencing of pooled DNA, it is challenging to distinguish true SNPs from sequencing errors as many variants are represented by only a single sequencing read. However, if the same variant is observed in more than one strain, it is more likely to be a real SNP than a sequencing error. Therefore, to enhance the accuracy of SNP detection we combined the WGS data from all wild-type strains and mutants, resulting in 50× genome coverage, and then selected only the variants that were present in at least three reads for inclusion in our SNP database (see Materials and Methods for filtering criteria). Although variants present in only one or two reads in the combined data could also represent real SNPs, many are likely to represent sequencing errors or alignment artifacts and therefore were not included in the database.

In total, we identified a set of 7.6 million SNPs (http://www.fishyskeleton.com), which is substantially greater than the 0.7 million zebrafish SNPs currently annotated in publically available databases. Of the SNPs in public databases, 85% were detected in at least one read in our sequence data, and 45% had been included in our SNP database since they met all filtering criteria (such as being present in at least three reads). Importantly, 7.3 million of the SNPs we identified were not previously annotated, thus vastly expanding our knowledge of genetic variation in zebrafish. Using the individual WGS data from pooled DNA for each mutant and wild-type strain, we were then able to classify each SNP within that sequence as being either heterogeneous (at least one read representing each SNP allele was observed) or homogeneous (all reads represented the same allele). In each pool, an average of ∼2 heterogeneous and ∼3 homogeneous SNPs were observed per kilobase of genomic sequence (Table S2).

Identification of strain-specific diversity

To allow us to predict the parental origin of alleles in mutant pools, which facilitates mapping based on homozygosity-by-descent, we identified alleles that differed between parental strains. In the 7.6 million total SNPs identified, an alternate allele (with respect to the Zv9 reference genome, which is based on the Tü strain) was observed at 3–4 million sites in each wild-type line (Table S1). Consistent with previous reports noting a high degree of variation within each zebrafish strain (Stickney et al. 2002; Guryev et al. 2006; Bradley et al. 2007; Coe et al. 2009), the vast majority of these sites were heterogeneous (i.e., had reads representing both the reference and the alternate alleles) (Table S1). Thus, to identify SNPs that differed between lines, we selected SNPs at which all reads represented the reference allele in one line, while the other line had at least one read representing an alternate allele. When only the SNPs with sequence coverage in all six lines (5.2 million) were considered, any two lines differed at ∼40% of loci (Figure S2A), which is in agreement with previous estimates of interstrain diversity (Stickney et al. 2002). The majority (72%) of SNPs were shared by at least three lines, while only 11% were unique to a single line (Figure S2B). For use in our mapping studies, we selected all sites at which alternate alleles were present in the strain used for outcrossing (TLF or WIK), but not in the strain used for mutagenesis (Tü). These alternate alleles were referred to as “mapping strain alleles” and consisted of 0.74 million and 1.2 million alleles for the TLF and WIK strains, respectively (Figure S2, C and D). In each mutant pool, these sites were analyzed for the presence or absence of the mapping strain allele (Table S2).

Mapping mutants using homozygosity-by-descent

We next mapped each mutant on the basis of homozygosity-by-descent. For each mutant pool, we scanned the WGS data for regions with two characteristics: having a reduced level of heterogeneity and a reduced level of SNPs originating from the outcrossed strain, relative to the genome-wide averages of these measures. To quantify these characteristics, we designed an algorithm that produced a “mapping score,” using sliding windows throughout the genome (Figure 1). Since we expected a characteristic footprint to span at least 10 cM on either side of the causative mutation (Figure S1), a window size of 20 cM, tiled at 0.25-cM intervals, was utilized. We based the window size on genetic distance (centimorgans) rather than physical distance (megabases), to take local recombination rates into account. This makes the analysis more accurate in regions close to centromeres and telomeres. Once regions with high mapping scores were identified for a particular mutant, we independently tested linkage to these regions by the use of SSLP or SNP markers on DNA pools as well as in individual progeny (Table S3). In each of the five mutants analyzed, we confirmed that the region with the highest mapping score was linked to the mutation (Figure 1).

Figure 1 .

Mapping zebrafish mutants based on homozygosity-by-descent. Individual graphs depict the mapping scores along each chromosome for the five different mutants (moto, frnt, hlw, wdd, and sump). The mapping score is calculated as the ratio of homogeneous to heterogeneous SNPs, multiplied by the ratio of reference alleles to mapping strain alleles in sliding windows. The size of the sliding windows is 20 cM with an overlap of 19.75 cM between adjacent windows. Physical distances were converted to genetic distances using markers from the MGH meiotic map that have been mapped onto the Zv9 reference genome. In each of the five mutants, the region with the highest mapping score in the genome (shaded arrows) was subsequently confirmed as containing the linked interval, using SSLP or SNP markers.

In some cases, other unlinked areas exhibited relatively high mapping scores. We postulate that these regions represent haplotype blocks that were, by chance, shared by the two parental fish used for the initial mapping cross. We asked whether these shared haplotype blocks could have been predicted on the basis of the WGS of the parental strains, but found that each block occurred in a region in which heterogeneous SNPs (and therefore more than one haplotype) were observed in each of the parental strains. Furthermore, these blocks occurred in different locations in each mutant analyzed. Thus, if multiple regions with a high mapping score are obtained, independent tests for linkage will be needed to distinguish shared haplotype blocks from the region linked to the causative mutation. The presence of multiple high mapping scores in the genome could also represent second-site modifiers of the phenotype. These regions could then be analyzed for sequence variants that alter the expressivity of the mutant phenotype.

Our approach has two major differences from those previously used to map C. elegans and A. thaliana mutants (Schneeberger et al. 2009; Cuperus et al. 2010; Doitsidou et al. 2010; Zuryn et al. 2010; Austin et al. 2011; Uchida et al. 2011). First, our analysis is based on genetic rather than physical distance. Second, we combine the levels of homogeneity and strain-specific SNP signatures to map the locus. We find that this analytical method provides a robust and reliable means to correctly map the region linked to the mutation in zebrafish (Figure S3 and Figure S4).

The genetic architecture of linked regions

We further refined the linked interval by identifying an area of homogeneity within the broader region defined by our mapping algorithm. Since 20 fish were pooled for each mutant, we expected the region of homogeneity to span, on average, 2.5 cM on either side of the causative mutation (one recombinant per 40 meioses). Because of the low resolution of the genetic map, we utilized 100-kb windows (rather than centimorgans) to facilitate fine mapping of the interval. Assuming random sampling of alleles with only ∼3× coverage, we expected and confirmed that linked regions containing two recombination events had an ∼81% reduction in heterogeneity compared to unlinked regions, while regions containing one recombination event had a reduction in heterogeneity of ∼90% (Figure 2 and Figure S1). We found that regions without recombination events were almost, but not completely, homogeneous, likely due to false positive variants resulting from sequencing errors or alignment artifacts. Therefore, we defined a candidate region of homogeneity as having a reduction in heterogeneity >90%. This approach allowed us to narrow down the candidate interval in each mutant to a region between 4 and 19 Mb in size (Table 1).

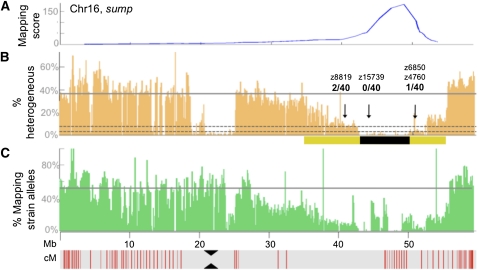

Figure 2 .

Genetic architecture of SNP diversity at a linked interval. (A) Graph of the mapping score across chromosome 16 in the sump mutant. This chromosome contained the highest mapping score in the genome. (B) Graph depicting the percentage of SNPs that were classified as heterogeneous in nonoverlapping 100-kb windows along chromosome (Chr)16. The solid gray line indicates the genome-wide average for SNPs classified as heterogeneous. Dotted gray lines indicate reductions in SNP heterogeneity of 90% (bottom line) and 81% (top line), respectively, compared to the genome-wide average. The yellow bar demarcates the region with a reduction in heterogeneity of at least 30%, while the black bar demarcates the candidate region, defined by a reduction in heterogeneity of >90%. Black arrows indicate the locations of SSLP markers used to confirm linkage to this interval by individually genotyping the 20 sump mutants that had been pooled for WGS. The fraction of recombination events per 40 meioses for each SSLP marker is indicated. (C) Graph showing the percentage of sites containing mapping-strain alleles, in nonoverlapping 100-kb windows along the chromosome. This percentage is calculated only for sites at which the strain used for mapping (WIK) showed an allele that was not observed in the strain used for mutagenesis (Tü). The gray line indicates the genome-wide average of the percentage of sites containing mapping-strain alleles. Physical distances in megabases along Chr16 are indicated. The red vertical lines in the gray bar below the graphs indicate genetic distances, with lines spaced at ∼1-cM intervals. The position of the centromere is indicated by black triangles.

Identifying candidate phenotype-causing mutations within linked intervals

One of the powerful aspects of WGS is that it provides a large amount of sequence information throughout the candidate interval, allowing for the exclusion of much of the sequence in the interval as harboring the causative mutation. Additionally, the sequence allows the potential to identify the causative change. In the five mutants analyzed, between 76% and 92% of the coding sequence within the candidate interval was covered by at least two sequencing reads (Table 1). We identified hundreds to thousands of homogeneous variants in each candidate interval, of which between 4 and 136 were predicted to be nonsynonymous. However, we could exclude most of these variants as being causative for the phenotype since we also observed them in the WGS from the other unaffected strains (Table 1). In two of the five mutants we identified the likely causative mutation as a nonsynonymous change covered by at least two reads; these particular changes are predicted to encode nonsense alleles. In the three other mutants, unique nonsynonymous changes covered by two or more reads were not detected, but between 7 and 22 nonsynonymous changes were present in sequences covered by one read (Table 1). Further studies will be required to determine whether these single-read variants represent sequencing errors, normal variation, or phenotype-causing mutations.

A benefit of having performed WGS is, apart from being able to map the mutation in all mutants analyzed and to identify candidate coding mutations, that >87% of the coding sequence within the interval could be excluded because it did not differ from the reference data set. A second benefit of having performed WGS is that homogeneous SNPs identified in the candidate interval can serve as markers to test for linkage in additional F2 fish, which will allow one to further refine the candidate interval.

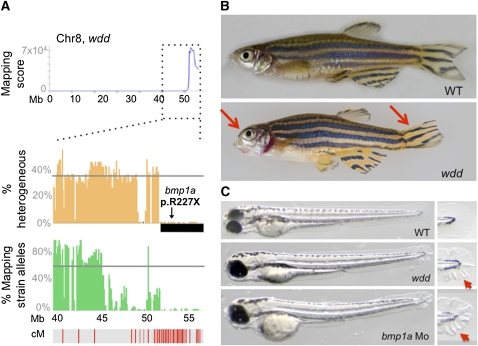

The nonsynonymous changes we identified in the welded (wddt31169) and the minamoto (motot31533) mutants exemplify the value of the WGS method. For the moto mutant, characterized by defective spermatogenesis, two nonsynonymous mutations (Table 1), covered by two and three reads respectively, were identified within the linked interval, one missense and one nonsense mutation. The nonsense mutation was confirmed to be homozygous in all 20 fish sequenced. This mutation lies within a novel gene (ENSDARG00000090664) that is conserved in vertebrates. Consistent with the observed spermatogenesis defects in the mutants, this gene is expressed in testes among vertebrates (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/unigene) and thus is a strong candidate for causing the moto phenotype. For the wdd mutant, characterized by its adult craniofacial phenotype, only one nonsynonymous change, which was supported by eight reads, was detected in the linked interval (Table 1). This change creates a nonsense mutation (p.R227X) in the gene encoding Bone morphogenetic protein 1a (Bmp1a). PCR amplification and capillary dideoxy sequencing of the genomic region in individual F2 mutants and siblings confirmed the mutation and linkage to the mutant phenotype (0 recombinants in 66 meioses). It previously had been shown that morpholino-mediated reduction of Bmp1a function in zebrafish impairs larval development, leading to a wavy fin fold phenotype (Jasuja et al. 2006). We detected a similar larval fin phenotype in wdd mutants and confirmed that this phenotype occurs in wild-type embryos injected with a morpholino targeting the translation initiation site of bmp1a (Figure 3). Thus we show that the nonsense mutation in bmp1a is the likely causative mutation underlying the wdd phenotype. With a causative mutation in hand, it is now possible to investigate the mechanistic basis of this skeletal phenotype.

Figure 3 .

Identification of a loss-of-function allele of Bmp1a that underlies the wdd mutant phenotype. (A) The mapping-score plot for wdd is shown for Chr8, which contained the highest mapping score in the genome. In the graphs below, the genetic architecture of the linked region is shown. Annotation is similar to Figure 2. The location of the nonsense mutation within bmp1a that lies in the candidate interval is indicated (arrow). (B) Lateral view of adult wild-type and homozygous wdd mutant fish. Mutant fish are characterized by frontonasal shortening of the skull and deformed tailfins (red arrows). (C) Lateral view of wild-type, wdd mutant, and bmp1a morpholino-injected larvae. Mutant and morphant larvae show a similar characteristic wavy appearance of their fin folds (red arrowheads) at 3 dpf, which is not observed in wild-type larvae. Insets show a higher magnification of the distal part of the finfold.

Minimum genome coverage needed for mapping

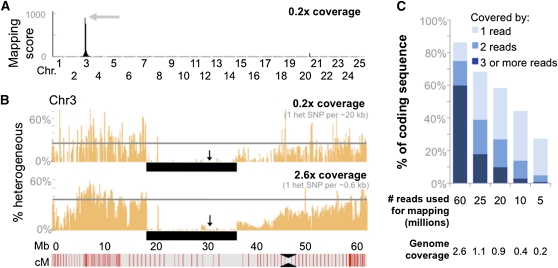

Our analysis showed that ∼3× genome coverage was sufficient to correctly map each mutant to a defined interval, to cover >87% of coding sequence within the candidate interval, and to identify a manageable number of variants as being potential causative mutations. To determine whether lower genome coverage would be sufficient for mapping and mutation detection, we applied the same mapping algorithm to randomly selected subsets of the total sequence reads obtained for each mutant. Utilizing only 5 million reads, which is equivalent to ∼0.2× genome coverage, we could still reliably identify the linked regions (Figure 4 and Figure S5). However, with 0.2× genome coverage, only 5% of coding sequence in the linked interval was covered by ≥2 reads, and 73% was not sequenced at all (Figure 4). Thus, using this method, it is feasible to map multiple mutants simultaneously by barcoding ∼14 mutant DNA libraries and then sequencing a pool of these libraries on a single lane of an Illumina HiSeq apparatus. However, with this “bulk mapping” approach it would be unlikely to identify the causative mutations using the generated sequence alone.

Figure 4 .

Mapping of mutants using only ∼0.2× genome coverage. (A) Graph depicting the genome-wide mapping score plot for the moto mutant generated with a randomly selected subset (5 million) of the total sequencing reads, which results in a genome coverage of 0.2×. (B) Graph depicting the percentage of SNPs that were classified as heterogeneous in nonoverlapping 100-kb windows along Chr3. The arrow indicates the location of a SNP marker that was used to confirm linkage (0 recombinants in 40 meioses). While the overall number of detectable heterogeneous SNPs is reduced with a genome-wide coverage of only 0.2×, the boundaries of the linked interval can be identified just as well as with 2.6× coverage. The black bar underlies the region of homogeneity. (C) Graph depicting the loss in coverage of coding sequence that occurs as genome-wide coverage decreases.

Discussion

We show that recessive zebrafish mutations can be efficiently mapped and cloned using low-coverage WGS of only 20 pooled mutant progeny. While WGS has been used in other experimental models, such as C. elegans and A. thaliana (Schneeberger et al. 2009; Cuperus et al. 2010; Doitsidou et al. 2010; Zuryn et al. 2010; Austin et al. 2011; Uchida et al. 2011), the size and polymorphic diversity of the zebrafish genome posed unique challenges. By constructing an extensive SNP database using WGS from six different wild-type lines, we increased the accuracy of mapping as well as the ability to distinguish phenotype-causing mutations from previously unannotated SNPs. This newly identified SNP database, containing millions of SNPs, is an order of magnitude larger than the SNPs previously annotated within publically available databases. This large database allowed us to identify strain-specific SNP signatures, which facilitated our detection of intervals that were homozygous-by-descent.

An alternative strategy of mapping mutants using WGS would be to separately sequence pools of mutants and unaffected siblings, rather than using a comparison to wild-type strains. With the limited recombination rate within the 20 fish sequenced, both strategies would provide similar resolution of the mapping interval. Using a sequence data set representing ∼50× coverage, we increase the accuracy of identifying SNPs within the mapping interval without the need for low-coverage sequence data from siblings. Additionally, analysis of the siblings for each mutant would double the cost per mutant analyzed. We think that the strain-specific and reference SNP databases we created provide a more efficient means of analyzing sequence data from multiple mutants in parallel. This SNP data set can be utilized by a large number of researchers to facilitate mapping of mutants (data and scripts available at http://www.fishyskeleton.com).

It is important to note that the detection of candidate mutations depends not only on the genome coverage obtained by WGS, but also on the quality and extent of the genome assembly that is used as a reference; in regions with poor genome assembly, lack of detection of a causative mutation will not be remedied by higher sequencing depth. Further improvements in assembly of the zebrafish genome, in the SNP database, and in massively parallel sequencing will enhance the sensitivity and specificity of our mapping approach. At present, low-coverage WGS using pooled DNA samples provides a fast and efficient means for mapping and identifying recessive mutations in zebrafish, allowing for more timely determination of altered gene function and systematic analysis of genetic regulation of vertebrate development and physiology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Iris Koch, Ursula Schach, Jennifer Zenker, Brigitte Walderich, and Hans-Georg Frohnhoefer at the Max-Planck Institute Tübingen as well as Christian Lawrence and Jason Best at the Children’s Hospital Boston facilities for help with maintaining and providing fish from their respective facilities. The authors also thank David R. Beier, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, for discussions and sharing unpublished ideas and Tom Carney at the Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, Singapore, for discussion about his unpublished work on bmp1. M.E.B. is an Albert J. Ryan Fellow. M.L.W. is an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. M.P.H is supported by a Glenn Foundation Award and a New Scholars Award from the Ellison Medical Foundation.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: M. Johnston

Literature Cited

- Arnold C. N., Xia Y., Lin P., Ross C., Schwander M., et al. , 2011. Rapid identification of a disease allele in mouse through whole genome sequencing and bulk segregation analysis. Genetics 187: 633–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin, R. S., D. Vidaurre, G. Stamatiou, R. Breit, N. J. Provart et al, 2011 Next-generation mapping of Arabidopsis genes. Plant J. 67: 715–725. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bowen M. E., Boyden E. D., Holm I. A., Campos-Xavier B., Bonafe L., et al. , 2011. Loss-of-function mutations in PTPN11 cause metachondromatosis, but not ollier disease or maffucci syndrome. PLoS Genet. 7: e1002050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley K. M., Elmore J. B., Breyer J. P., Yaspan B. L., Jessen J. R., et al. , 2007. A major zebrafish polymorphism resource for genetic mapping. Genome Biol. 8: R55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe T. S., Hamilton P. B., Griffiths A. M., Hodgson D. J., Wahab M. A., et al. , 2009. Genetic variation in strains of zebrafish (danio rerio) and the implications for ecotoxicology studies. Ecotoxicology 18: 144–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuperus J. T., Montgomery T. A., Fahlgren N., Burke R. T., Townsend T., et al. , 2010. Identification of MIR390a precursor processing-defective mutants in Arabidopsis by direct genome sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 466–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doitsidou M., Poole R. J., Sarin S., Bigelow H., Hobert O., 2010. C. elegans mutant identification with a one-step whole-genome-sequencing and SNP mapping strategy. PLoS ONE 5: e15435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler R., Rauch G. J., Geiger-Rudolph S., Albrecht A., van Bebber F., et al. , 2007. Large-scale mapping of mutations affecting zebrafish development. BMC Genomics 8: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guryev V., Koudijs M. J., Berezikov E., Johnson S. L., Plasterk R. H., et al. , 2006. Genetic variation in the zebrafish. Genome Res. 16: 491–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasuja R., Voss N., Ge G., Hoffman G. G., Lyman-Gingerich J., et al. , 2006. Bmp1 and mini fin are functionally redundant in regulating formation of the zebrafish dorsoventral axis. Mech. Dev. 123: 548–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nüsslein-Volhard C., Dahm R., 2002. Zebrafish: A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Schneeberger K., Ossowski S., Lanz C., Juul T., Petersen A. H., et al. , 2009. SHOREmap: simultaneous mapping and mutation identification by deep sequencing. Nat. Methods 6: 550–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobreira N. L., Cirulli E. T., Avramopoulos D., Wohler E., Oswald G. L., et al. , 2010. Whole-genome sequencing of a single proband together with linkage analysis identifies a Mendelian disease gene. PLoS Genet. 6: e1000991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickney H. L., Schmutz J., Woods I. G., Holtzer C. C., Dickson M. C., et al. , 2002. Rapid mapping of zebrafish mutations with SNPs and oligonucleotide microarrays. Genome Res. 12: 1929–1934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida N., Sakamoto T., Kurata T., Tasaka M., 2011. Identification of EMS-induced causal mutations in a non-reference Arabidopsis thaliana accession by whole genome sequencing. Plant Cell Physiol. 52: 716–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuryn S., Le Gras S., Jamet K., Jarriault S., 2010. A strategy for direct mapping and identification of mutations by whole-genome sequencing. Genetics 186: 427–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.