Abstract

Voltage-gated Na+ (Nav) channels are composed of a pore-forming α-subunit and one or more auxiliary β-subunits. The present study investigated the regulation by the β-subunit of two Na+ channels (Nav1.6 and Nav1.8) expressed in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons. Single cell RT-PCR was used to show that Nav1.8, Nav1.6, and β1–β3 subunits were widely expressed in individually harvested small-diameter DRG neurons. Coexpression experiments were used to assess the regulation of Nav1.6 and Nav1.8 by β-subunits. The β1-subunit induced a 2.3-fold increase in Na+ current density and hyperpolarizing shifts in the activation (−4 mV) and steady-state inactivation (−4.7 mV) of heterologously expressed Nav1.8 channels. The β4-subunit caused more pronounced shifts in activation (−16.7 mV) and inactivation (−9.3 mV) but did not alter the current density of cells expressing Nav1.8 channels. The β3-subunit did not alter Nav1.8 gating but significantly reduced the current density by 31%. This contrasted with Nav1.6, where the β-subunits were relatively weak regulators of channel function. One notable exception was the β4-subunit, which induced a hyperpolarizing shift in activation (−7.6 mV) but no change in the inactivation or current density of Nav1.6. The β-subunits differentially regulated the expression and gating of Nav1.8 and Nav1.6. To further investigate the underlying regulatory mechanism, β-subunit chimeras containing portions of the strongly regulating β1-subunit and the weakly regulating β2-subunit were generated. Chimeras retaining the COOH-terminal domain of the β1-subunit produced hyperpolarizing shifts in gating and increased the current density of Nav1.8, similar to that observed for wild-type β1-subunits. The intracellular COOH-terminal domain of the β1-subunit appeared to play an essential role in the regulation of Nav1.8 expression and gating.

Keywords: voltage-gated sodium channels, nociception

voltage-gated Na+ (Nav) channels are responsible for the rising phase of action potentials in many excitable cells and consist of a pore-forming α-subunit and one or more auxiliary β-subunits. The TTX-resistant Nav1.8 channel is highly expressed in small-diameter dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons and trigeminal ganglions. It exhibits slow activation, slow inactivation, and rapid repriming kinetics (Sangameswaran et al. 1996; Vijayaragavan et al. 2001). The TTX-sensitive Nav1.6 channel is found in many different neuronal populations in the peripheral nervous system and central nervous system (CNS) and exhibits fast activation and inactivation kinetics (Chatelier et al. 2010). To date, at least five isoforms of auxiliary β-subunits (β1–β4 subunits as well as the β1A-subunit, a splice variant of the β1-subunit) have been identified (Chahine et al. 2005). They are transmembrane proteins containing an extracellular Ig domain, a single transmembrane segment, and a small intracellular COOH-terminal domain. The β1- and β3-subunits interact noncovalently with the α-subunit, whereas the β2- and β4-subunits interact covalently with the α-subunit via a disulfide bond. The β-subunits form a family of cell adhesion molecules and modulate the channel gating, location, expression levels, and functional properties of α-subunits (Isom 2002b). The β-subunits also regulate cell migration and aggregation as well as interactions with the cytoskeleton (Malhotra et al. 2000).

The β1-subunit is expressed abundantly in intermediate- to large-diameter (>25 μm) DRG neurons and at much lower levels in small-diameter (<25 μm) DRG neurons (Oh et al. 1995). Increased β1-subunit mRNA levels in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord after nerve injuries indicate that the β1-subunit may be involved in the generation of neuropathic pain (Blackburn-Munro and Fleetwood-Walker 1999) and may also regulate Na+ channel function. Coexpression of β1-subunits with Nav1.7 or Nav1.8 in Xenopus oocytes accelerates current decay kinetics, negatively shifts steady-state curves, and significantly enhances the expression of Nav1.8. In addition, Nav1.8 + β1 channels rapidly enter into slow inactivation states at hyperpolarized voltages, causing a frequency-dependent reduction of current amplitudes and modulating the firing frequency in tsA201 cells and Xenopus oocytes (Zhao et al. 2007; Vijayaragavan et al. 2004). The β1-subunit promotes neurite outgrowth in cerebellar granule neurons and plays a critical role in neuronal development (Davis et al. 2004). β1-Subunit-null mice exhibit a hyperexcitable phenotype, including epilepsy, ataxia, abnormal neuronal pathfinding, and a prolonged QT interval (Lopez-Santiago et al. 2007; Chen et al. 2004).

The β2-subunit is expressed at low levels in small- to large-diameter DRG neurons (Takahashi et al. 2003) but is strongly expressed throughout the CNS (Gastaldi et al. 1998). So far, information on the expression of the β2-subunit in neuropathic pain models is contradictory. Immunohistochemistry and Western blot analyses have revealed that β2-subunit protein levels are markedly upregulated for at least 4 wk in DRG neurons after spared nerve injuries (Pertin et al. 2005) but are downregulated in cervical sensory ganglia after avulsion injuries (Coward et al. 2001). Other studies have found that the β2-subunit selectively increases TTX-sensitive Na+ channel mRNA and protein expression, particularly of Nav1.7, in small-fast DRG neurons (Lopez-Santiago et al. 2006). In addition, β2-subunit-null mice exhibit a reduced response to neuropathic and inflammatory pain (Pertin et al. 2005).

The β3-subunit is expressed at high levels in small-diameter DRG neurons and in the I/II and X layers of the spinal cord. The distribution of β3-subunits in DRG neurons and the CNS exhibits a complementary pattern with that of the β1-subunit (Morgan et al. 2000). Unlike β1- and β2-subunits, the β3-subunit has a clearer role in neuropathic pain in that β3-subunit mRNA and protein levels are upregulated in various neuropathic pain models (Shah et al. 2001; Takahashi et al. 2003). Furthermore, β3-subunit mutations are associated with early-onset lone atrial fibrillation, and β3-subunit-null mice exhibit cardiac ventricular electrophysiology abnormalities (Hakim et al. 2008; Olesen et al. 2010).

The β4- and β2-subunits share a similar expression pattern in the CNS, but the β4-subunit is more abundantly expressed in DRG neurons than the β2-subunit, with higher levels in large-diameter DRG neurons and lower levels in small- and intermediate-diameter neurons (Yu et al. 2003). The β4-subunit has been reported to induce negative shifts in the activation of several Na+ channel subtypes, including Nav1.1, Nav1.2, Nav1.4, and Nav1.6, indicating that the β4-subunit may modulate the electrical properties of neurons by allowing Na+ channels to activate at more negative voltages (Yu et al. 2003; Chen et al. 2008; Aman et al. 2009). Since a free peptide derived from its cystoplasmic tail replicates the action of the endogenous blocking protein, the β4-subunit may be indirectly involved in the generation of resurgent currents (Grieco et al. 2005). Furthermore, recent studies have shown that the β4-subunit plays a role in the pathophysiology of a cardiac disease, long QT syndrome type 3, and neurological Huntington's disease (Oyama et al. 2006; Medeiros-Domingo et al. 2007).

Using single cell RT-PCR techniques, we show that a large percentage of these small-diameter neurons (40–60%) express β1-, β2-, and β3-subunits, whereas only ∼10% express the β4-subunit. We investigated how these β-subunits modulate the expression and gating properties of two different Na+ channel subtypes: Nav1.6 and Nav1.8. We demonstrate that the β1-subunit induces a significant increase in the current density of Nav1.8 but has no effect on the current density of Nav1.6. In addition, the COOH-terminal domain of the β1-subunit is involved in the modulation of the Nav1.8 channel based on the results of experiments with a β1 COOH-terminal deletion variant and β1/β2-subunit chimeras harboring various regions of the β1-subunit together with the entire β2-subunit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of DRG neurons.

Seven-day-old rat pups were anesthetized with isoflurane before decapitation. The rats were handled in accordance with the principles and guidelines of the local animal care committee, from which we received approval. DRGs were harvested from all accessible levels. The ganglia were incubated for 30 min at 37°C in 2 ml of HBSS-HEPES containing 1.5 mg/ml collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) followed by 1 mg/ml trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) for an additional 30 min. Trypsin was removed, and the ganglia were transferred to L-15 Leibovitz media supplemented with 1% FBS (GIBCO), 2 mM glutamine, 24 mM NaHCO3, 38 mM glucose, 2% penicillin-streptomycin (GIBCO), and 50 ng/ml nerve growth factor (Sigma-Aldrich). The ganglia were disrupted using fire-polished Pasteur pipettes, and dissociated neurons were placed in 35-mm dishes containing 2 ml of supplemented Leibovitz media.

Single cell RT-PCR.

Intact neurons were harvested by drawing the cells into large-bore 20-μm-diameter pipettes containing 20 μl of RNase-free water and were rapidly frozen for further analysis. Random hexamer primers (65 ng, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were added to 10-μl aliquots of cell lysates, which were heated to 70°C for 3 min and rapidly cooled on ice. mRNA was reverse transcribed in a 25-μl reaction containing Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (200 units, Fisher Bioreagents), 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.3), 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, 0.5 mM dNTPs, and RNase inhibitor (1 U/μl, Promega). The remaining 10-μl aliquots of cell lysate were treated in an identical fashion except that water was substituted for reverse transcriptase in the reaction mixture. Thereafter, the first-strand cDNA synthesized in the reactions with or without reverse transcriptase (1–3 μl) was amplified in two successive rounds of a standard PCR protocol (30 cycles each) using nested gene-specific primers for Na+ channel β1–β4-subunits. Primer sets were designed to span one or more exon-intron borders to eliminate the possibility of contamination by genomic DNA. The PCR amplification was based on Taq polyermase (Roche Biochemicals) and used the following protocol: 94°C/1 min, 55°C/0.5 min, and 72°C/1 min (30 cycles). Additional controls included blanks in which the PCR amplification was performed in the absence of added reaction mixture with and without reverse transcriptase and a full RT-PCR analysis of the bath solution immediately surrounding the harvested neurons. Amplifications of the reaction without reverse transcriptase, the PCR blank, and the bath solution immediately surrounding the harvested neurons routinely failed to produce amplicons. The sizes of the cDNA amplicons were estimated by running the samples on 2% agarose gels, after which the DNA was purified (QiaEx II, Qiagen) and sequenced.

Gene transfections and cell cultures.

Two human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cell lines stably expressing human Nav1.6 and rat Nav1.8 were used. Both HEK-293 cell lines were grown under standard tissue culture conditions (5% CO2, 37°C) in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with FBS (10%), l-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (10 mg/ml; GIBCO-BRL Life technologies). Rat auxiliary β1-, β2-, and β3-subunits were cloned in our laboratory as previously described (Vijayaragavan et al. 2004). The rat β4-subunit was a gift from Dr. Lori L. Isom (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI). The Na+ channel β1–β4-subunits and CD8 (empty vector) were constructed in the piRES vector (Invitrogen), respectively (piERS/CD8/β1, piERS/CD8/β2, piERS/CD8/β3, piERS/CD8/β4, and piERS/CD8). HEK-293 cell lines stably expressing Nav1.6 or Nav1.8 were transiently transfected with the same amount of individual β1–β4-subunits or empty vector piRES/CD8 DNA. Transient transfections were carried out using the calcium phosphate method as previously described (Zhao et al. 2007). Transfected cells were briefly preincubated with CD8 antibody-coated beads before currents were recorded (Dynabeads M450 CD8-a). HEK-293 cells expressing the piRES/CD8/β bicistronic vector were decorated with CD8 beads, which were used to identify cells for recording currents (Zhao et al. 2007).

The β1/β2-subunit chimeras (β211, β221, and β112) and COOH-terminal deletion variant (β11Δ) were generous gifts from Dr. Thomas Zimmer (Institute of Physiology II, Friedrich Schiller University, Jena, Germany). β211 contains the extracellular domain of the β2-subunit and the transmembrane and intracellular domains of the β1-subunit. β221 contains the extracellular and transmembrane domains of the β2-subunit and the intracellular domain of the β1-subunit. β112 contains the extracellular and transmembrane domains of the β1-subunit and the intracellular domain of the β2-subunit. β11Δ contains only the extracellular and transmembrane domains of the β1-subunit. The 41 amino acid residues that form the COOH-terminal tail were deleted (see Fig. 6A). β211, β221, β112, and β11Δ were constructed in the piRES vector for expression in mammalian cells (piERS/CD8/ β211, piERS/CD8/ β221, piERS/CD8/ β112, and piERS/CD8/ β11Δ) and were individually transfected into the Nav1.8-expressing HEK-293 cell line. Transient transfections of the β1/β2-subunit chimeras and the COOH-terminal deletion variant were performed using the calcium phosphate method as previously described (Zhao et al. 2007). Transfected cells were identified for patch-clamp analysis by preincubation with CD8 antibody-coated beads, as mentioned above.

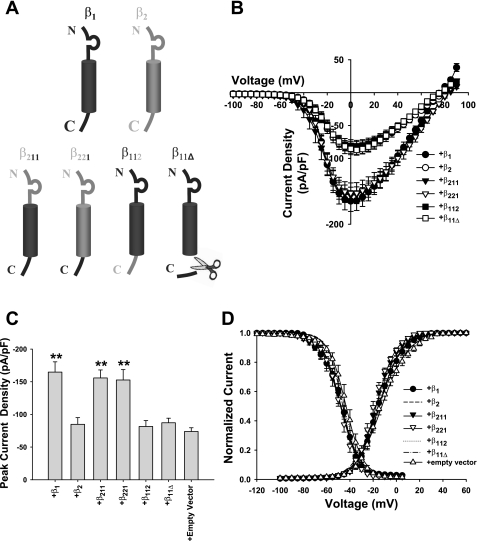

Fig. 6.

A: schematic representation of the construction of β1/β2-subunit chimeras and the deletion mutant. Top, typical structure of wild-type β1- and β2-subunits; bottom, the NH2-terminal (N), COOH-terminal (C), and transmembrane-spanning segments of the β1-subunit were systematically replaced by corresponding segments of the β2-subunit. β211, β221, and β112 are β1/β2-subunit chimeras constructed by site-directed mutagenesis; β11Δ is a COOH-terminal deletion mutant of the β1-subunit. B: current-voltage relationship showing the average current densities of Nav1.8 currents in HEK-293 stable cells transiently transfected with β1 (n = 14), β2 (n = 13), β211(n = 14), β221 (n = 9), β112 (n = 14), or β11Δ (n = 16). The protocol is the same as in Fig. 2A. C: histogram showing the current densities of Nav1.8 channels transiently coexpressing wild-type, chimera, and mutant β-subunits. The current densities of the β1, β211, and β221 groups were significant larger than that of the empty vector control group (**P < 0.01) but similar to each other. D: composite figure showing steady-state activation (right) and inactivation (left). The activation curves were generated using the same protocol as in Fig. 2A. Inactivation was measured using the same protocol as in Fig. 3C. The smooth lines of activation and inactivation are fits to a Boltzmann function (see data analysis in materials and methods). For clarity, we show only the symbols for the β1, β211, and β221 groups, which exhibited significant differences compared with the empty vector group, and removed the symbols for other groups (β2, β112, and β11Δ). When β1, β211, or β221 were coexpressed with Nav1.8, the steady-state activation curves exhibited a negative shift compared with the empty vector group (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05). When β1 or β221 were coexpressed with Nav1.8, the steady-state inactivation curves exhibited a negative shift compared with the empty vector control group (P < 0.05), whereas coexpression of β2, β221, β112, and β11Δ with Nav1.8 did not have a significant effect on voltage-dependent inactivation (P > 0.05). The values of V1/2 and kv are shown in Table 2.

Whole cell patch-clamp recordings.

Macroscopic Na+ currents from rat DRG neurons and HEK-293 stable cells were recorded using the whole cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique. For whole cell patch-clamp recordings of DRG neurons, the pipette solution was composed of (in mM) 100 CsF, 25 CsCl, 10 NaCl, 1 EGTA, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4). The bath solution was composed of (in mM) 140 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1.5 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4). TTX was bath applied at a final concentration of 300 nM. For HEK-293 stable cells, the pipette solution was composed of (in mM) 5 NaCl, 135 CsF, 10 EGTA, and 10 Cs-HEPES. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 using 1 N CsOH. The bath solution was composed of (in mM) 150 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1.5 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, and 10 Na-HEPES. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 with 1 N NaOH.

The liquid junction potential was measured as described by Neher (1992) (+7 mV) and was consistent to the one calculated using pCLAMP (+7.1 mV, Molecular Devices, Union City, CA). To correct for this junction potential, the pipette voltage was held at −7 mV, and the pipette offset was zeroed before making a giga seal. After that, no additional correction was necessary, and the applied voltages are the reported voltages.

The recordings were taken exactly 10 min after the whole cell configuration was obtained to allow the current to stabilize and fully dialyze the cell with pipette solution. Na+ currents were recorded at room temperature (22–23°C). Command pulses were generated, and currents were recorded using pCLAMP software (version 8.0) and an Axopatch 200 amplifier (Molecular Devices). Patch electrodes were fashioned from borosilicate glass (Corning 8161) and coated with silicone elastomer (Sylgard, Dow-Corning, Midland, MI) to minimize stray capacitance. Current recordings were taken using low-resistance electrodes (<1 MΩ), and the series resistance was compensated at values of ≥80% to minimize patch-clamp errors. Whole cell currents were filtered at 5 kHz, digitized at 10 kHz, and stored on a microcomputer equipped with an analog-to-digital converter (Digidata 1300, Molecular Devices).

Average current-voltage curves were obtained by plotting the current density (in pA/pF) versus the voltage. For the construction of activation curves, Na+ conductance (GNa) was calculated from the peak current (INa) using the following equation: GNa = INa/(V − ENa), where V is the test potential and ENa is the reversal potential. Normalized GNa was plotted against the test potentials. For the construction of inactivation curves, the peak current was normalized relative to the maximal value and plotted against the conditioning pulse potential. Steady-state activation and inactivation curves were fit to a Boltzmann equation of the following form: G/Gmax (or I/Imax) = 1/[1 + exp(V1/2 − V)/kv], where G is conductance, Gmax is maximal conductance, I is peak current, Imax is maximal current, V1/2 is the voltage at which the channels are half-maximally activated or inactivated, and kv is the slope factor. The window current results from the overlap of voltage-dependent activation and inactivation that determines a range of potentials (window) at which Na+ channels are noninactivated and available for activation. Using the V1/2 and kv values of voltage-dependent activation and inactivation, the probability of Na+ channels being within the window was calculated using the following equation: (1/{1 + exp[(V1/2 activation − V)/kv activation]}) × (1/{1+ exp[(V − V1/2 inactivation)/kv inactivation]}).

Analysis of electrophysiological data.

Data were analyzed using a combination of pCLAMP software (version 9.0, Molecular Devices), Microsoft Excel, and SigmaPlot for Windows (version 11.0, SPS, Chicago, IL). Data are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Single cell analysis of Na+ channel and β-subunit expression in DRG sensory neurons.

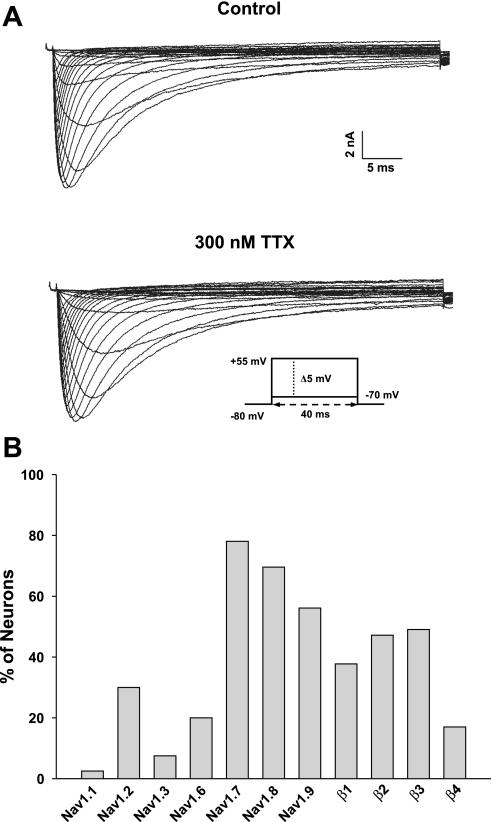

Figure 1A shows whole cell Na+ currents of a typical small-diameter (<25 μm) DRG neuron before (control) and after bath application of 300 nM TTX. The slowly inactivating TTX-resistant Na+ current observed in this neuron is characteristic of Nav1.8 channels, which are known to be preferentially expressed in small-diameter sensory neurons (Sangameswaran et al. 1996). Single cell RT-PCR was used to investigate the expression of Na+ channels and auxiliary β-subunits in this population. Figure 1B shows the analyses of 53 individually harvested neurons. A high percentage of these neurons (80–85%) expressed Nav1.7, Nav1.8, and Nav1.9 channels, consistent with what has recently been reported for small-diameter sensory neurons (Ho and O'Leary 2010). Between 40% and 60% of these neurons expressed at least one β1-, β2-, or β3-subunit. Only a small percentage (17%) expressed the β4-subunit, suggesting that this subunit is not widely expressed in these neurons. These data also provided insights into the overlap of β-subunit expression. The β2-β3 combination (39% neurons) was most frequently observed followed by β1-β3 (28%), β1-β2 (22%), β2-β4 (13%), β3-β4 (9%), and β1-β4 (7%). Overall, the data indicate that β-subunits are differentially expressed in subpopulations of small-diameter neurons, where they may regulate the expression and gating properties of Nav1.7, Nav1.8, and Nav1.9 channels present in these neurons.

Fig. 1.

A: whole cell Na+ currents measured from a small-diameter (<25 μm) dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons isolated from a newborn rat. Currents were elicited by depolarizing voltage pulses from −70 mV in 5-mV increments from a holding potential of −80 mV. The top trace is the whole cell Na+ current measured in 70 mM external Na+ solution. The bottom trace is the current measured from the same cell after bath application of 300 nM TTX. B: histogram showing the expression of seven neuronal voltage-gated Na+ (Nav) channels and their β-subunits in 53 DRG sensory neurons using standard RT-PCR.

Regulation of expression levels of Nav1.8 by β1–4 subunits of HEK-293 stable cells.

Western blots showed no detectable endogenous expression of β1–β4-subunits in HEK-293 cells (Aman et al. 2009). HEK-293 cells are thus well suited for assessing the effect of auxiliary β-subunits on the expression levels and properties of heterologously expressed Nav1.6 and Nav1.8 channels.

Transient transfections of Nav1.8 in HEK-293 cells only achieved partial cell surface expression of the channel (John et al. 2004). To increase the expression of Nav1.8, we constructed HEK-293 stable cells. Current amplitudes ranged between 500 and 1,500 pA, and currents resisted a high concentration (10 μM) of TTX, as previously reported (Zhao et al. 2007).

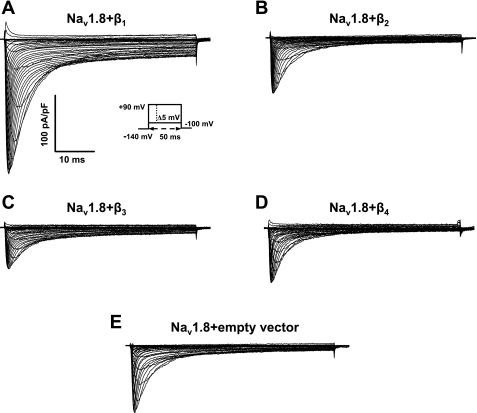

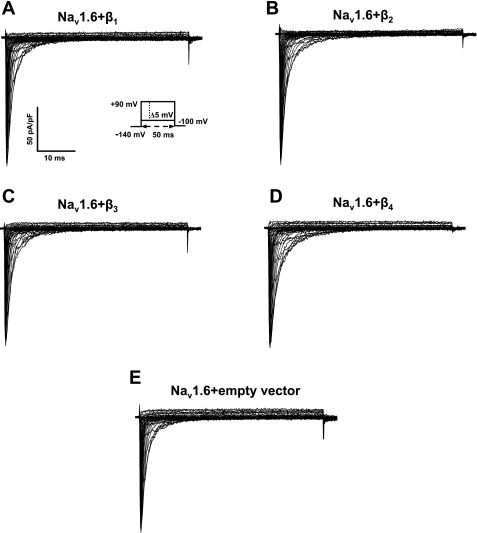

To test the impact of Na+ channel β-subunits on the expression of Nav1.8, we transiently transfected individual β1–β4-subunits or empty vector into HEK-293 cells stably expressing Nav1.8. Figure 2 shows representative Nav1.8 currents recorded from the HEK-293 stable cell line transiently transfected with individual β1–β4-subunits or empty vector and normalized to membrane capacitance. For all groups except for the β4-subunit coexpression group, Nav1.8 currents activated at approximately −45 mV, and the peak inward current occurred at approximately −5 to 5 mV. The β4-subunit coexpression group activated earlier at −55 mV and reached its maximum at −10 mV. The reversal potential for all groups was ∼80 mV, or 6.2 mV less than the calculated value (86.2 mV; Fig. 3A). When cells were depolarized to 0 mV, coexpression of the β1-subunit induced a 2.3-fold increase in current density compared with the empty vector control (Nav1.8 + β1: −165.7 ± 13.6 pA/pF, n = 18, vs. control: 73.9 ± 5.7 pA/pF, n = 15). Coexpression of the β2- and β4-subunits in Nav1.8-expressing HEK-293 stable cells did not alter the expression of Nav1.8 (Nav1.8 + β2: −73.3 ± 4.2 pA/pF, n = 21, and Nav1.8 + β4: −86.4 ± 8.0 pA/pF, n = 14, P > 0.05). Interestingly, expression of the β3-subunit induced a 31% reduction in Nav1.8 current amplitude (−51.0 ± 3.0 pA/pF, n = 19) compared with the empty vector control (Fig. 3B). The regulation of Nav1.8 expression by β1–β4 subunits encouraged us to investigate the influence of these regulatory subunits on the gating properties of the Nav1.8 channel.

Fig. 2.

Representative Nav1.8 current traces in human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 stable cells transiently coexpressed with individual β1 (A)-, β2 (B)-, β3 (C)-, or β4 (D)-subunits or empty vector (E) and normalized by membrane capacitance. The inset in A shows the protocol. Currents were elicited by depolarizing steps between −100 and 90 mV in 5-mV increments for 50 ms. Cells were held at a holding potential of −140 mV.

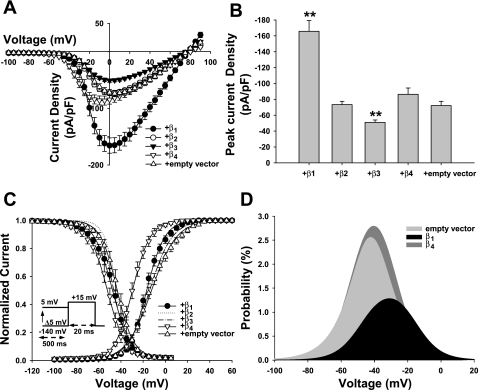

Fig. 3.

Whole cell Nav1.8 currents in HEK-293 stable cells transiently transfected with individual β1–β4-subunits or empty vector. A: current-voltage relationship of Nav1.8 transfected with individual β1 (n = 18)-, β2 (n = 21)-, β3 (n = 19)-, or β4 (n = 14)-subunits or empty vector (n = 15). Current densities were measured by normalizing current amplitudes to the membrane capacitance and were plotted versus voltage. The experimental protocol is the same as in Fig. 2A. B: histogram showing the average current densities of Nav1.8 coexpressed with different β-subunits or empty vector. When cells were depolarized to 0 mV, coexpression with the β1-subunit produced a 2.3-fold increase in Nav1.8 current density compared with the empty vector control (**P < 0.01). The β2- and β4-subunits caused no increase in Nav1.8 current density (P > 0.05), whereas the β3-subunit induced a 30% decrease in Nav1.8 current density (**P < 0.01). C: composite figure showing the steady-state activation and inactivation of Nav1.8 coexpressed with individual β1–β4-subunits or empty vector. For clarity, we only show the symbols of the empty vector control group and the group that exhibited a significant difference, and we removed the symbols of the other groups. As such, only the symbols for the β1, β4, and control groups are shown, and the symbols for the β2 and β3 groups have been removed. Activation curves were generated using the same protocol as in Fig. 2A. Coexpression of β1- or β4-subunits with Nav1.8 induced a hyperpolarizing shift of the activation curve from −15 to 10 mV for the β1 group (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05) and from −50 to 10 mV (P < 0.01) for the β4 group. Steady-state inactivation was determined using 20-ms test pulses to 15 mV after 500-ms prepulses to potentials ranging from −140 to 5 mV (see the inset under the inactivation curves for the protocol). Like voltage-dependent activation, coexpression of β1- or β4-subunits also caused a hyperpolarizing shift of the inactivation curves from −70 to −60 mV for the β1-subunit (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05) and from 0 to −30 mV for the β4-subunit (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05). Both the activation and inactivation curves were fitted to a single Boltzmann function (see materials and methods). The midpoints (V1/2) and slope factors (kv) of the activation and inactivation curves are shown in Table 1. D: effects of β1- and β4-subunits on the Nav1.8 window current. The activation and inactivation curves of the Na+ channels overlap at a (relatively narrow) distinct voltage range (window), predicting a steady Na+ conductance over this range. The probability of Nav1.8 channels being within this window was calculated using the equation given in materials and methods. The β1-subunit decreased the window current, and the peak probability shifted to a more depolarized potential, whereas the β4-subunit slightly increased the window current of Nav1.8.

Effect of β-subunits on the gating properties of Nav1.8 in HEK-293 stable cells.

Voltage-dependent activation of Nav1.8 was assessed from the peak Na+ conductance and plotted versus test voltages (Fig. 3C and Table 1). Activation of Nav1.8 current was modified after the transient transfection of β1- and β4-subunits. For the β1-subunit group, the Boltzmann analysis of Nav1.8 conductance yielded a V1/2 of activation of −16.5 ± 1.4 mV (n = 18), which was 4.0 mV more negative than that of the empty vector control group (−12.5 ± 1.7 mV, n = 15, P < 0.01). This was in good agreement with the value recorded using TTX-resistant DRG neurons (Zhao et al. 2007). The V1/2 of the activation curve was not sensitive to β2- or β3-subunit expression, and no shift in the steady-state activation curves was observed (P > 0.05). When the β4-subunit was expressed, the V1/2 value of the activation curve produced a significant −16.7-mV shift (−29.2 ± 1.7 mV, n = 14, P < 0.01).

Table 1.

Effect of individual β-subunits on the activation and inactivation of Nav1.8 and Nav1.6 channels in HEK-293 cells

| Activation |

Steady-State Inactivation |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1/2, mV | n | kv, mV | n | V1/2, mV | n | kv, mV | n | |

| Nav1.8 | ||||||||

| +β1 | −16.5 ± 1.4† | 18 | −7.5 ± 0.4† | 18 | −47.8 ± 1.5* | 18 | 7.7 ± 0.9† | 18 |

| +β2 | −13.9 ± 1.0 | 21 | −9.7 ± 0.5 | 21 | −43.7 ± 0.8 | 19 | 5.4 ± 0.2 | 19 |

| +β3 | −14.0 ± 1.2 | 19 | −9.8 ± 0.3 | 19 | −45.9 ± 1.4 | 15 | 6.0 ± 0.4 | 15 |

| +β4 | −29.2 ± 1.7† | 14 | −7.2 ± 0.5† | 14 | −52.5 ± 2.0† | 14 | 7.3 ± 0.8 | 8 |

| +Empty vector | −12.5 ± 1.7 | 15 | −10.5 ± 0.7 | 15 | −43.2 ± 2.0 | 13 | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 13 |

| Nav1.6 | ||||||||

| +β1 | −34.8 ± 1.7 | 8 | −5.8 ± 0.2 | 8 | −72.2 ± 0.6 | 9 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 9 |

| +β2 | −35.3 ± 2.6 | 8 | −5.6 ± 0.3 | 8 | −73.3 ± 2.0 | 8 | 6.4 ± 0.1 | 8 |

| +β3 | −37.3 ± 1.1 | 8 | −5.9 ± 0.2 | 8 | −75.8 ± 1.3 | 8 | 6.5 ± 0.3 | 8 |

| +β4 | −44.3 ± 0.5† | 11 | −5.6 ± 0.2 | 11 | −77.1 ± 1.2 | 11 | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 11 |

| +Empty vector | −36.7 ± 1.1 | 9 | −5.6 ± 0.3 | 9 | −74.3 ± 2.3 | 9 | 6.0 ± 0.2 | 9 |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of cells. HEK-293 cells, human embryonic kidney-293 cells; V1/2, voltage at which Na+ channels are half-maximally activated or inactivated; kv, slope factor.

P < 0.05 and

P < 0.01 compared with the control (+empty vector) group.

To investigate the effects of β1–β4 subunits on steady-state Nav1.8 inactivation (Fig. 3C and Table 1), we applied a two-pulse voltage-clamp protocol composed of 500-ms prepulses to potentials between −140 mV and 5 mV followed by test pulses to 15 mV. Like steady-state activation, when individual β1–β4-subunits were coexpressed with Nav1.8, the β1- and β4-subunits caused −4.6-mV (P < 0.05) and −9.3-mV (P < 0.01) shifts in steady-state inactivation, respectively. Little modulation of voltage-dependent inactivation was observed when Nav1.8 was coexpressed with β2- or β3-subunits (P > 0.05).

The overlapping area of the steady-state activation and inactivation curves shown in Fig. 3C gives a range of potentials (window) at which some channels are in the open state but do not undergo fast inactivation. Na+ channels activated in this way cause “window currents” (Hodgkin et al. 1952). The leftward shifts in steady-state activation and inactivation caused by the β1- and β4-subunits should induce alterations in window currents. Figure 3D shows that the Nav1.8 channels were probably within this window, that is, were inactivated and were available for activation when coexpressed with β1- or β4-subunits. Compared with the empty vector control, the small but significant hyperpolarization caused by the β1-subunit shortened the window, indicating a lower probability of Nav1.8 being activated. The peak probability shifted to a more depolarized potential (β1: −36 mV and control: −42 mV), with a smaller peak probability (β1: 1.2% and control: 2.6%) and a smaller fraction of Nav1.8 channels (the sum of all probabilities) that would be activated near the resting membrane potential (β1: 0.43% and control: 0.73%). In contrast, the substantial leftward shift caused by the β4-subunit slightly enhanced the probability, with a peak probability of 2.8% at −41 mV and a larger fraction (0.81%) of Nav1.8 channels that would be activated near the resting membrane potential.

Effect of β1–β4-subunits on the expression and gating properties of Nav1.6 in HEK-293 stable cells.

To study the specificity of β-subunit regulation, we investigated the effect of β1–β4 subunits on the expression of Nav1.6 in the HEK-293 stable cell line. We transiently transfected individual β1–β4-subunits or empty vector in HEK-293 cells stably expressing Nav1.6. Figure 4 shows representative current traces of Nav1.6 recorded from HEK-293 cells and normalized to membrane capacitance. Figure 5A shows the current-voltage relations of Nav1.6 currents. The activation threshold for these Nav1.6 currents was approximately −60 mV, and the maximum inward currents ranged from −25 to −15 mV. The reversal potential was ∼85 mV in the five groups, which was in good agreement with the calculated value (86.2 mV). Coexpression of β1–β4-subunits with Nav1.6 in HEK-293 cells failed to increase the current densities of Nav1.6 compared with the empty vector control (Nav1.6 + β1: −127.0 ± 11.8 pA/pF, n = 9; Nav1.6 + β2: −127.2 ± 8.7 pA/pF, n = 8; Nav1.6 + β3: −125.8 ± 13.1 pA/pF, n = 8; Nav1.6 + β4: −124.6 ± 13.4 pA/pF, n = 11; and control: −120.5 ± 14.9 pA/pF, n = 9).

Fig. 4.

Representative Nav1.6 current traces in HEK-293 cells transiently transfected with individual β1 (A)-, β2 (B)-, β3 (C)-, or β4 (D)-subunits or empty vector (E) and normalized by membrane capacitance. The inset in A shows the protocol. Nav1.6 currents were evoked with depolarizing voltage steps from −100 to 90 mV in 5-mV increments for 50 ms at a holding potential of −140 mV.

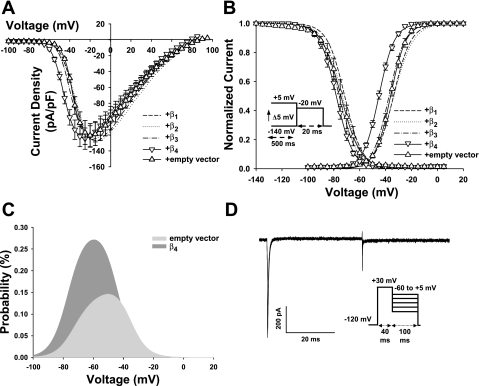

Fig. 5.

Whole cell Nav1.6 currents in HEK-293 stable cells transiently transfected with individual β1–β4-subunits or empty vector. A: current-voltage relations of Nav1.6 currents were obtained using the same protocol as in Fig. 4A. For clarity, we removed the overlapping symbols of the β1-, β2-, and β3-subunit transfection groups and only kept their corresponding lines (β1: n = 9, β2: n = 8, β3: n = 8, β4: n = 11, and empty vector: n = 9). The β1–β4-subunits did not modulate the expression of Nav1.6 in HEK-293 cells. B: voltage dependence of activation and inactivation of Nav1.6 coexpressed with different β-subunits or empty vector. For clarity, we show only the symbols for the β4 and control groups and have removed the symbols for the other groups. The activation curves were generated using the same protocol as in Fig. 4A. Inactivation was measured using 500-ms prepulses to potentials between −140 and 5 mV. The fraction of available current was determined using test pulses to −20 mV at a holding potential of −140 mV (see the inset under the inactivation curve for the protocol). The smooth lines of activation and inactivation are fits to a Boltzmann function (see data analysis in materials and methods). Coexpression of the β4-subunit caused a negative shift in the activation curve from −65 to −20 mV (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05). However, coexpression of β1–β4-subunits did not affect the voltage-dependent inactivation of Nav1.6 in HEK-293 cells. The values of V1/2 and kv are shown in Table 1. C: effect of the β4-subunit on the Nav1.6 window current. The y-axis shows the probability of Nav1.6 channels being within the window, which was measured using the equation given in materials and methods. Coexpression of the β4-subunit increased the probability of Nav1.6 opening within the window and shifted the peak probability in a more hyperpolarizing direction. D: representative resurgent Na+ current in HEK-293 cells coexpressing Nav1.6 and the β4-subunit. The voltage protocol used to elicit the currents is shown under the current trace. HEK-293 cells coexpressing Nav1.6 and the β4-subunit were depolarized from a holding potential of −120 mM by a prepulse to 30 mV for 40 ms to activate and inactivate Na+ channels. Each prepulse was followed by a single 100-ms test pulse to potentials ranging from −60 to 5 mV in 5-mV increments. Resurgent currents were not detected in all HEK-293 cells coexpressing Nav1.6 and the β4-subunit.

Figure 5B is a composite figure showing the steady-state activation and inactivation curves of Nav1.6. Coexpression of β1-, β2-, or β3-subunits with Nav1.6 did not cause a shift in the activation and inactivation curves compared with the empty vector control group. However, the β4-subunit induced a 7.6-mV hyperpolarized shift in the V1/2 value of Nav1.6 activation but did not appreciably alter the voltage dependence of inactivation. As such, only the β4-subunit appeared to regulate Nav1.6 voltage dependence in HEK-293 cells. The leftward shift of steady-state activation of Nav1.6 caused by the β4-subunit produced an enhanced window current, as shown in Fig. 5C. Compared with the empty vector control, coexpression of the β4-subunit increased the opening probability of Nav1.6 within the window (β4: 0.26% and control: 0.15%). The peak probability of the β4-subunit group was shifted in a more hyperpolarizing direction (β4: −60 mV and control: −50 mV), with an increased fraction of Nav1.6 channels that would be activated near the resting membrane potential (β4: 0.08% and control: 0.045%).

When Na+ channels open transiently during recovery from inactivation, they generate a “resurgent current,” which has been reported to be carried mainly by Nav1.6 α-subunits. The cytoplasmic tail of the β4-subunit may be the endogenous open channel blocker responsible for the production of resurgent currents (Grieco et al. 2005; Raman and Bean 1997). However, we did not detect a resurgent current in Nav1.6-expressing HEK-293 cells coexpressing the β4-subunit (Fig. 5D) or empty vector (data not shown). Similarly, no resurgent current was observed in Nav1.8-expressing HEK-293 cells cotransfected with the β4-subunit (data not shown).

Differential regulation of the expression and gating properties of Nav1.8 in HEK-293 stable cells by β1/β2-subunit chimeras and a β1 COOH-terminal deletion variant.

As indicated by our above results, only the β1-subunit significantly increased the current density of Nav1.8 (2.3-fold) in HEK-293 cell stable cells. The β2-subunit did not regulate the expression and gating properties of Nav1.8. We took advantage of the nonmodulating β2-subunit to investigate the molecular basis of β1-subunit-mediated enhancement of Nav1.8 expression. Auxiliary β-subunits are transmembrane proteins composed of a NH2-terminal extracellular domain, a single transmembrane domain, and an intracellular COOH-terminal domain (Isom 2002a) (Fig. 6A, top). In the present study, we used β1/β2-subunit chimeras (β211, β221 and β112) and a β1 COOH-terminal deletion variant (β11Δ) to identify the molecular regions of the β1-subunit that are involved in the modulation of Nav1.8 (Fig. 6A, bottom).

Coexpression of chimera β211, which was composed of the β2-subunit extracellular domain and the β1-subunit transmembrane and intracellular domains, increased the current density (−155.8 ± 12.2 pA/pF, n = 14) compared with control cells (−73.9 ± 5.7 pA/pF, n = 15, P < 0.01). To determine whether the β1-subunit intracellular domain was sufficient to modulate the current density of Nav1.8, chimera β221, which was composed of the β2-subunit extracellular and transmembrane domains and the β1-subunit intracellular domain, was coexpressed with Nav1.8. β221 increased the current density of Nav1.8 (−152.7 ± 16.0 pA/pF, n = 9, P < 0.01). Current densities of the β211 and β221 groups were similar to the value observed with the β1-subunit group (−164.8 ± 15.7 pA/pF, n = 14, P > 0.05). No increase in the current density of Nav1.8 was observed in the β112 and β11Δ groups, which contain the NH2-terminus and transmembrane domain of the β1-subunit but lack the COOH-terminus of the β1-subunit (β112: −81.5 ± 9 pA/pF, n = 14, and β11Δ: −87.2 ± 7 pA/pF, n = 16, P > 0.05; Fig. 6, B and C). This suggested that the increase in the peak current densities of Nav1.8 observed in the wild-type β1, β211, and β221 groups is due to the COOH-terminal region of the β1-subunit.

To determine whether the increase in the peak current densities of Nav1.8 caused by COOH-terminal of the β1-subunit was accompanied by changes in the biophysical properties of Nav1.8, the voltage dependence of activation and inactivation of wild-type channels, chimeras, and the deletion variant were studied (Fig. 6D). Compared with the empty vector control group, the β1, β211, and β221 groups produced significant negative shifts in the V1/2 values of the activation curves by 5.2, 4.8, and 6.6 mV (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05), respectively, and in the V1/2 values of the inactivation curves by 4.5, 4.9, and 5.8 mV (P < 0.05), respectively. No significant differences in the voltage dependence of activation and inactivation were observed among the β1, β211, and β221 groups.

DISCUSSION

The main goal of the present study was to investigate the regulation of Nav1.6 and Nav1.8 channels by auxiliary β-subunits. These Na+ channels are widely expressed in primary sensory neurons, where they contribute to the rapid rising phase of action potentials (Chahine et al. 2005). We used a combination of single cell RT-PCR of acutely dissociated DRG neurons and heterologous expression experiments to identify the β-subunits expressed in small-diameter sensory neurons and to investigate their regulation of functional Na+ channels, which are known to be expressed in these neurons. Our results indicated that small-diameter DRG neurons widely express Nav1.6 and Nav1.8 channels and auxiliary β1–β3-subunits. These findings are in agreement with previous work using RT-PCR, in situ hybridization, and double labeling coupled with immunohistochemistry (Morgan et al. 2000; Takahashi et al. 2003; Yu et al. 2003).

Regulation of Nav1.8 by auxiliary β-subunits.

The single cell RT-PCR analysis of acutely dissociated DRG neurons indicated that Nav1.8 channels are widely expressed in small-diameter neurons (Fig. 1B), which is consistent with recent work showing that the TTX-resistant Nav1.8 channel is highly expressed in unmyelinated C-fibers (Ho and O'Leary 2010). These neurons also express β1-, β2-, and β3-subunits, raising the possibility that these auxiliary subunits may associate with and regulate endogenous Nav1.8 channels expressed in these neurons. To further investigate this potential regulation, Nav1.8 and β-subunits were coexpressed in HEK-293 cells, and the biophysical properties of the channel complexes were assessed using an electrophysiology approach. In the absence of auxiliary subunits, heterologously expressed Nav1.8 channels produced robust Na+ currents that activated at relatively depolarized voltages (−50 mV) and displayed properties similar to the dominant TTX-resistant Na+ current of DRG neurons (Zhao et al. 2007). Coexpression of the β1-subunit increased the current density twofold and produced hyperpolarizing shifts in activation (−4 mV) and steady-state inactivation (−4.6 mV). These shifts produced a twofold reduction in the window current, resulting in a decrease in the fraction of Nav1.8 channels predicted to be open at voltages near the resting membrane potential (approximately −65 mV) of sensory neurons (Zhao et al. 2007). Our results indicated that Nav1.8 and the β1-subunit are coexpressed in the same population of DRG sensory neurons and that the association with the β1-subunit increases the cell surface expression and alters the gating of the channels. Coexpression of the β3-subunit did not alter Nav1.8 gating but produced a 31% decrease in the peak current density (Fig. 3B). Whereas β2 subunits were widely expressed in small-diameter DRG neurons (47%), this auxiliary subunit did not significantly alter the expression or gating of heterologously expressed Nav1.8 channels. The β4-subunit produced dramatic shifts in activation (−16.7 mV) and inactivation (−9.3 mV), resulting in an increase in the window current. These changes predicted that Nav1.8 + β4 channels would activate at more hyperpolarized membrane potentials and would increase the likelihood of a persistent Na+ current at more hyperpolarizing voltages. β4-Subunit regulation may increase the excitability of DRG neurons expressing this combination of subunits. However, unlike the β1-subunit, the β4-subunit was expressed in a relatively small percentage (17%) of small-diameter sensory neurons. This suggested that, although β4-subunits are potent regulators of Nav1.8 channels, they are expressed in a small subpopulation of unmyelinated C-fibers.

Regulation of Nav1.6 by auxiliary β-subunits.

Nav1.6 channels are mainly expressed in large-diameter (>30 μm) myelinated sensory neurons (Ho and O'Leary 2010), where they are predominantly located at the nodes of Ranvier (Krzemien et al. 2000; Caldwell et al. 2000). Heterologously expressed Nav1.6 channels generate a rapidly inactivating TTX-sensitive current that activates at a relatively hyperpolarized (−60 mV) voltage (Fig. 5A). The β1-subunit and Nav1.6 have reciprocal functions, such that β1-subunit-mediated neurite outgrowth requires Na+ current carried by Nav1.6, and the β1-subunit is required for normal expression/high-frequency action potential firing of Nav1.6 at the axon initial segment (Brackenbury et al. 2010). Our results showed that coexpression of β-subunits (β1–β4) does not alter the peak current density or voltage-dependent gating of heterologously expressed Nav1.6 channels (Fig. 5). The sole exception was the β4-subunit, which produced a hyperpolarizing shift (−7.6 mV) in Nav1.6 activation. This may be significant because it resulted in a twofold increase in the window current and shifted Nav1.6 activation into a range of voltages considered to be near the resting membrane potential of sensory neurons. These changes may increase the excitability of Nav1.6 channels, leading to a reduction in the threshold for initiating action potentials in large-diameter, low-threshold sensory neurons.

The COOH-terminal domain of the β1-subunit is critical for Nav1.8 regulation.

Previous studies have used β-subunit chimeras to identify the structural domains of the auxiliary subunits required for regulating Na+ channel function. Early studies of the neuronal Nav1.2 channel indicated that the NH2-terminus of the β1-subunit is sufficient to fully recapitulate the accelerated inactivation, increased expression, and shifts in voltage-dependent activation and inactivation produced by the full-length β1-subunit (McCormick et al. 1998). A similar role for the NH2-terminal domain of the β1-subunit has been previously postulated for the skeletal muscle Nav1.4 channel (Chen and Cannon 1995). These findings were further supported by studies showing that the regions important for α-β1 interactions are located within the extracellular loops of Nav1.2 and Nav1.4 channels (Makita et al. 1996; Qu et al. 1999). Subsequent work has implicated the intracellular COOH-terminal domain of the β1-subunit as another important determinant of α-β1 interactions and of Nav1.2 regulation (Meadows et al. 2001). Current evidence suggests that both NH2- and COOH-terminals of the β1-subunit contribute to α-β1 interactions and the functional regulation of neuronal and skeletal muscle Na+ channels. These findings contrast sharply with the results of studies on the cardiac Nav1.5 channel, where the membrane-spanning domain coupled with secondary interactions with either the NH2- or COOH-terminal of the β1-subunit were reported to be required for Nav1.5 regulation (Zimmer and Benndorf 2002). These results point to substantial differences in the mechanisms of β1-subunit regulation of neuronal, skeletal muscle, and cardiac Na+ channels.

We used chimeras of the strongly regulating β1-subunit and weakly regulating β2-subunit to identify the structural domains required for Nav1.8 regulation. The intracellular COOH-terminal domain of the β1-subunit appeared to be required for the increase in Na+ current density and the hyperpolarizing shifts in the activation and inactivation of Nav1.8 channels. The observed changes in expression and gating were not altered by replacing the extracellular NH2-terminus or membrane-spanning domains of the β1-subunit with those of the β2-subunit or by deleting the COOH-terminus of the β1-subunit. These findings differ substantially from previous studies of neuronal and skeletal muscle Na+ channels, where the extracellular domain of the β1-subunit appeared to play a more prominent role in Na+ channel regulation. Coimmunoprecipitation studies have identified sites in the COOH-terminus of the β1-subunit and neuronal Nav1.1 channels that directly contribute to α-β1 interactions (Spampanato et al. 2004). A similar interaction between the intracellular COOH-terminus of the β1-subunit and Nav1.8 may contribute to the observed increase in the expression and functional regulation of these channels.

The β1- and β2-subunits are both cell adhesion molecules that interact in a trans-homophilic fashion, resulting in ankyrin recruitment to the plasma membrane at points of cell-cell contact. Only the β1-subunit can heterophilically interact with contactin, leading to increased surface expression of Nav1.2 in CHL cells. β1/β2-Subunit chimeric studies in which the various regions of the β1 Ig loop were exchanged showed that the β1 Ig loop is not enough to induce full β1-subunit-mediated enhancement of the Nav1.2 cell surface (McEwen et al. 2004; Malhotra et al. 2000). Further studies showed that ankyrin recruitment by the β1-subunit depends on the phosphorylation of β1Y181, an intracellular tyrosine residue. A mutant of this residue (β1Y181E) inhibits β1-subunit-mediated ankyrin recruitment in response to homophilic adhesion and enhancement of Nav1.2 surface expression (Malhotra et al. 2002; McEwen et al. 2004). While the β3-subunit extracellular domain is homologous to the β1-subunit, the β3-subunit does not mediate the trans-homophilic cell adhesion that results in ankyrin recruitment (McEwen et al. 2009). Taken together, these findings provide support for the hypothesis that the COOH-terminus of the β1-subunit plays an essential role in the modulation of Na+ channel function (McEwen et al. 2009).

Previous studies of β-subunit regulation.

Previous studies have investigated the regulation of Nav1.8 channels by auxiliary β-subunits. Early work examining Nav1.8 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes failed to detect changes in current kinetics when the channels were coexpressed with the β1-subunit (Akopian et al. 1996; Sangameswaran et al. 1996). However, subsequent studies found that coexpression of the β1-subunit in oocytes accelerates inactivation kinetics, increases the current density, and produces hyperpolarizing shifts in the activation and steady-state inactivation of Nav1.8 channels (Vijayaragavan et al. 2004). A similar β1-subunit-induced shift in activation was reported for the heterologously expressed human Nav1.8 channel (Rabert et al. 1998). These observations are consistent with both our results and recent work showing that the β1-subunit increases the current density and produces hyperpolarizing shifts in the gating of Nav1.8 channels expressed in mammalian cells (Zhao et al. 2007).

There are conflicting results concerning the regulation of Nav1.8 channels by the β3-subunit. Coexpression of the β3-subunit in oocytes results in an increase in Nav1.8 current and a hyperpolarizing shift in activation (Shah et al. 2000). This contrasts with previous work showing that coexpression of the β3-subunit in oocytes produces a depolarizing shift in Nav1.8 inactivation but no change in current density (Vijayaragavan et al. 2004). β3-Subunits have been reported to directly bind to Nav1.8 channels via the COOH-terminus of the β3-subunit and to help translocate Nav1.8 from the endoplasmic reticulum to the plasma membrane (Zhang et al. 2008). However, in the present study, coexpression of the β3-subunit in mammalian cells produced a significant 31% decrease in Nav1.8 current density (Fig. 3B). This result is in agreement with a previous study showing that β3-subunits do not improve the functional expression of Nav1.8 in COS-7 cells (Swanwick et al. 2010). Collectively, these findings suggest that coexpression of the β3-subunit either has no effect or reduces Nav1.8 current without altering voltage dependence or gating kinetics. The role of the β3-subunit in neuropathic pain is closely associated with Nav1.3, both of which are upregulated after axotomy in a coordinated fashion. They have also been shown to be highly coexpressed in DRG neurons using the double-labeling method (Takahashi et al. 2003). The β3-subunit depolarizes the voltage-dependent activation and inactivation of Nav1.3 when expressed in HEK-293 cells and induces biphasic components of the inactivation curves, increasing the proportion of channels with slower inactivation kinetics (Cusdin et al. 2010).

The β2- and β4-subunits share 35% sequence similarity, and both subunits covalently associate with Na+ channels via disulfide bonds (Yu et al. 2003). In the present study, the β2-subunit did not alter the expression, kinetics, or voltage dependence of Nav1.8 channels (Table 1). This is in good agreement with previous work showing that the β2-subunit does not regulate Nav1.8 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Vijayaragavan et al. 2004). In contrast, the β4-subunit produced hyperpolarizing shifts in the activation of Nav1.8 and Nav1.6 channels. Similar changes in activation have been reported for Nav1.1, Nav1.2, Nav1.4, and Nav1.6 channels coexpressed with β4-subunits (Chen et al. 2008; Yu et al. 2003; Aman et al. 2009). The hyperpolarizing shift in activation produced by the β4-subunit expanded the predicted Nav1.8 window current (Fig. 3D) and increased the likelihood of Nav1.8 activation and persistent TTX-resistant Na+ currents at hyperpolarized voltages. While the COOH-terminal domain of the β4-subunit has been proposed to act as the endogenous open channel blocker of Na+ channels (Grieco et al. 2005), we could not detect a reduction in current density or resurgent currents when Nav1.6 and Nav1.8 channels were coexpressed with the β4-subunit.

Conclusions.

The present study examined the functional regulation of neuronal Nav1.6 and sensory neuron-specific Nav1.8 channels by auxiliary β-subunits. Single cell RT-PCR revealed that the Nav1.8 channel and several β-subunits (β1, β2, and β3) were coexpressed in the same population of small-diameter neurons. The high level expression of TTX-resistant Na+ currents and the preferential expression of Nav1.7, Nav1.8, and Nav1.9 transcripts in these neurons were consistent with what has been reported for unmyelinated C-fibers. Association with the β1-subunit increased Na+ current density and produced shifts in gating, leading to Nav1.8 activation at voltages near the resting membrane potential of sensory neurons. The predicted increase in TTX-resistant Na+ currents could have important implications for the electrical excitability of sensory neurons. Previous work has shown that β1-subunits are predominately expressed in medium- and large-diameter DRG neurons, a pattern that is not altered in animal models of nerve injury (Oh et al. 1995; Takahashi et al. 2003). While Nav1.8 channels and β1-subunits are differentially expressed in small- and large-diameter sensory neurons, these subunits may overlap in subpopulations of these neurons (Ho and O'Leary 2010; Oh et al. 1995; Takahashi et al. 2003). Our single cell analysis showed that 44% of the neurons expressing Nav1.8 also express transcripts coding for the β1-subunit, which provides support for this possibility. Further studies are required to determine whether these β1-subunits are associated with Nav1.8 channels and whether they regulate the expression and gating of Nav1.8 channels in these neurons. (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of β1/β2-subunit chimeras and β1 COOH-terminal deletion mutant on the activation and inactivation of Nav1.8 channels in HEK-293 cells

| Activation |

Steady-State Inactivation |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1/2, mV | n | kv, mV | n | V1/2, mV | n | kv, mV | n | |

| Nav1.8 + β1 | −17.7 ± 1.8* | 14 | −8.1 ± 0.6† | 14 | −47.7 ± 1.5* | 13 | 7.8 ± 0.0.5† | 13 |

| Nav1.8 + β2 | −14.4 ± 1.2 | 13 | −9.4 ± 0.7 | 13 | −45.9 ± 0.9 | 11 | 6.5 ± 0.5 | 11 |

| Nav1.8 + β211 | −17.3 ± 1.5* | 14 | −7.9 ± 0.3† | 14 | −48.1 ± 2.2* | 14 | 7.1 ± 0.3* | 14 |

| Nav1.8 + β221 | −19.1 ± 1.1† | 9 | −8.2 ± 0.5† | 9 | −49.0 ± 1.2* | 12 | 7.0 ± 0.4* | 12 |

| Nav1.8 + β112 | −14.5 ± 2.0 | 14 | −9.0 ± 0.5* | 14 | −44.7 ± 1.4 | 12 | 6.6 ± 0.6 | 12 |

| Nav1.8 + β11Δ | −15.7 ± 2.1 | 16 | −8.9 ± 0.5† | 16 | −47.3 ± 1.3 | 15 | 7.3 ± 0.6* | 15 |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of cells.

P < 0.05 and

P < 0.01 compared with the Nav1.8 + empty vector group (values are shown in Table 1).

GRANTS

This study was supported by grants from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Québec and the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR, INO-77909) to M. Chahine; and by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM-078244) to M. E. O'Leary.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- Akopian AN, Sivilotti L, Wood JN. A tetrodotoxin-resistant voltage-gated sodium channel expressed by sensory neurons. Nature 379: 257–262, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman TK, Grieco-Calub TM, Chen C, Rusconi R, Slat EA, Isom LL, Raman IM. Regulation of persistent Na current by interactions between β subunits of voltage-gated Na channels. J Neurosci 29: 2027–2042, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn-Munro G, Fleetwood-Walker SM. The sodium channel auxiliary subunits β1 and β2 are differentially expressed in the spinal cord of neuropathic rats. Neuroscience 90: 153–164, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackenbury WJ, Calhoun JD, Chen C, Miyazaki H, Nukina N, Oyama F, Ranscht B, Isom LL. Functional reciprocity between Na+ channel Nav1.6 and β1 subunits in the coordinated regulation of excitability and neurite outgrowth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 2283–2288, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JH, Schaller KL, Lasher RS, Peles E, Levinson SR. Sodium channel Nav1.6 is localized at nodes of Ranvier, dendrites, and synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 5616–5620, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahine M, Ziane R, Vijayaragavan K, Okamura Y. Regulation of Nav channels in sensory neurons. Trends Pharmacol Sci 26: 496–502, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatelier A, Zhao J, Bois P, Chahine M. Biophysical characterisation of the persistent sodium current of the Nav1.6 neuronal sodium channel: a single-channel analysis. Pflugers Arch 460: 77–86, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Cannon SC. Modulation of Na+ channel inactivation by the β1 subunit: a deletion analysis. Pflügers Arch 431: 186–195, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Westenbroek RE, Xu X, Edwards CA, Sorenson DR, Chen Y, McEwen DP, O'Malley HA, Bharucha V, Meadows LS, Knudsen GA, Vilaythong A, Noebels JL, Saunders TL, Scheuer T, Shrager P, Catterall WA, Isom LL. Mice lacking sodium channel β1 subunits display defects in neuronal excitability, sodium channel expression, and nodal architecture. J Neurosci 24: 4030–4042, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Yu FH, Sharp EM, Beacham D, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Functional properties and differential neuromodulation of Nav1.6 channels. Mol Cell Neurosci 38: 607–615, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coward K, Jowett A, Plumpton C, Powell A, Birch R, Tate S, Bountra C, Anand P. Sodium channel β1 and β2 subunits parallel SNS/PN3 α-subunit changes in injured human sensory neurons. Neuroreport 12: 483–488, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusdin FS, Nietlispach D, Maman J, Dale TJ, Powell AJ, Clare JJ, Jackson AP. The sodium channel β3-subunit induces multiphasic gating in Nav1.3 and affects fast inactivation via distinct intracellular regions. J Biol Chem 285: 33404–33412, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TH, Chen C, Isom LL. Sodium channel β1 subunits promote neurite outgrowth in cerebellar granule neurons. J Biol Chem 279: 51424–51432, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastaldi M, Robaglia-Schlupp A, Massacrier A, Planells R, Cau P. mRNA coding for voltage-gated sodium channel β2 subunit in rat central nervous system: cellular distribution and changes following kainate-induced seizures. Neurosci Lett 249: 53–56, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco TM, Malhotra JD, Chen C, Isom LL, Raman IM. Open-channel block by the cytoplasmic tail of sodium channel β4 as a mechanism for resurgent sodium current. Neuron 45: 233–244, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakim P, Gurung IS, Pedersen TH, Thresher R, Brice N, Lawrence J, Grace AA, Huang CL. Scn3b knockout mice exhibit abnormal ventricular electrophysiological properties. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 98: 251–266, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C, O'Leary M. Single-cell analysis of sodium channel expression in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci 46: 159–166, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF, Katz B. Measurement of current-voltage relations in the membrane of the giant axon of Loligo. J Physiol 116: 424–448, 1952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isom LL. The role of sodium channels in cell adhesion. Front Biosci 7: 12–23, 2002a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isom LL. β subunits: players in neuronal hyperexcitability? Novartis Found Symp 241: 124–138, 2002b [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John VH, Main MJ, Powell AJ, Gladwell ZM, Hick C, Sidhu HS, Clare JJ, Tate S, Trezise DJ. Heterologous expression and functional analysis of rat NaV1.8 (SNS) voltage-gated sodium channels in the dorsal root ganglion neuroblastoma cell line ND7–23. Neuropharmacol 46: 425–438, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzemien DM, Schaller KL, Levinson SR, Caldwell JH. Immunolocalization of sodium channel isoform NaCh6 in the nervous system. J Comp Neurol 420: 70–83, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Santiago LF, Meadows LS, Ernst SJ, Chen C, Malhotra JD, McEwen DP, Speelman A, Noebels JL, Maier SK, Lopatin AN, Isom LL. Sodium channel Scn1b null mice exhibit prolonged QT and RR intervals. J Mol Cell Cardiol 43: 636–647, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Santiago LF, Pertin M, Morisod X, Chen C, Hong S, Wiley J, Decosterd I, Isom LL. Sodium channel β2 subunits regulate tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium channels in small dorsal root ganglion neurons and modulate the response to pain. J Neurosci 26: 7984–7994, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makita N, Bennett PB, George AL. Molecular determinants of voltage-gated sodium channel α-β subunit interaction. Biophys J 70: A8, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra JD, Kazen-Gillespie K, Hortsch M, Isom LL. Sodium channel β subunits mediate homophilic cell adhesion and recruit ankyrin to points of cell-cell contact. J Biol Chem 275: 11383–11388, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra JD, Koopmann MC, Kazen-Gillespie KA, Fettman N, Hortsch M, Isom LL. Structural requirements for interaction of sodium channel β1 subunits with ankyrin. J Biol Chem 277: 26681–26688, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick KA, Isom LL, Ragsdale D, Smith D, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of Na+ channel function in the extracellular domain of the β1 subunit. J Biol Chem 273: 3954–3962, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen DP, Chen C, Meadows LS, Lopez-Santiago L, Isom LL. The voltage-gated Na+ channel β3 subunit does not mediate trans homophilic cell adhesion or associate with the cell adhesion molecule contactin. Neurosci Lett 462: 272–275, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen DP, Meadows LS, Chen C, Thyagarajan V, Isom LL. Sodium channel β1 subunit-mediated modulation of Nav1.2 currents and cell surface density is dependent on interactions with contactin and ankyrin. J Biol Chem 279: 16044–16049, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows L, Malhotra JD, Stetzer A, Isom LL, Ragsdale DS. The intracellular segment of the sodium channel β1 subunit is required for its efficient association with the channel α subunit. J Neurochem 76: 1871–1878, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros-Domingo A, Kaku T, Tester DJ, Iturralde-Torres P, Itty A, Ye B, Valdivia C, Ueda K, Canizales-Quinteros S, Tusie-Luna MT, Makielski JC, Ackerman MJ. SCN4B-encoded sodium channel β4 subunit in congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation 116: 134–142, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan K, Stevens EB, Shah B, Cox PJ, Dixon AK, Lee K, Pinnock RD, Hughes J, Richardson PJ, Mizuguchi K, Jackson AP. β3: an additional auxiliary subunit of the voltage-sensitive sodium channel that modulates channel gating with distinct kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 2308–2313, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E. Correction for liquid junction potentials in patch clamp experiments. Methods Enzymol 207: 123–131, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh Y, Sashihara S, Black JA, Waxman SG. Na+ channel β1 subunit mRNA: differential expression in rat spinal sensory neurons. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 30: 357–361, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesen MS, Jespersen T, Nielsen JB, Liang B, Moller DV, Hedley P, Christiansen M, Varro A, Olesen SP, Haunso S, Schmitt N, Svendsen JH. Mutations in sodium channel β-subunit SCN3B are associated with early-onset lone atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res 89: 786–793, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama F, Miyazaki H, Sakamoto N, Becquet C, Machida Y, Kaneko K, Uchikawa C, Suzuki T, Kurosawa M, Ikeda T, Tamaoka A, Sakurai T, Nukina N. Sodium channel β4 subunit: down-regulation and possible involvement in neuritic degeneration in Huntington's disease transgenic mice. J Neurochem 98: 518–529, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertin M, Ji RR, Berta T, Powell AJ, Karchewski L, Tate SN, Isom LL, Woolf CJ, Gilliard N, Spahn DR, Decosterd I. Upregulation of the voltage-gated sodium channel β2 subunit in neuropathic pain models: characterization of expression in injured and non-injured primary sensory neurons. J Neurosci 25: 10970–10980, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Rogers JC, Chen SF, McCormick KA, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Functional roles of the extracellular segments of the sodium channel α subunit in voltage-dependent gating and modulation by β1 subunits. J Biol Chem 274: 32647–32654, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabert DK, Koch BD, Ilnicka M, Obernolte RA, Naylor SL, Herman RC, Eglen RM, Hunter JC, Sangameswaran L. A tetrodotoxin-resistant voltage-gated sodium channel from human dorsal root ganglia, hPN3/SCN10A. Pain 78: 107–114, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman IM, Bean BP. Resurgent sodium current and action potential formation in dissociated cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci 17: 4517–4526, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangameswaran L, Delgado SG, Fish LM, Koch BD, Jakeman LB, Stewart GR, Sze P, Hunter JC, Eglen RM, Herman RC. Structure and function of a novel voltage-gated, tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channel specific to sensory neurons. J Biol Chem 271: 5953–5956, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah BS, Gonzalez MI, Bramwell S, Pinnock RD, Lee K, Dixon AK. β3, a novel auxiliary subunit for the voltage gated sodium channel is upregulated in sensory neurones following streptozocin induced diabetic neuropathy in rat. Neurosci Lett 309: 1–4, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah BS, Stevens EB, Gonzalez MI, Bramwell S, Pinnock RD, Lee K, Dixon AK. β3, a novel auxiliary subunit for the voltage-gated sodium channel, is expressed preferentially in sensory neurons and is upregulated in the chronic constriction injury model of neuropathic pain. Eur J Neurosci 12: 3985–3990, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spampanato J, Kearney JA, de Haan G, McEwen DP, Escayg A, Aradi I, MacDonald BT, Levin SI, Soltesz I, Benna P, Montalenti E, Isom LL, Goldin AL, Meisler MH. A novel epilepsy mutation in the sodium channel SCN1A identifies a cytoplasmic domain for β subunit interaction. J Neurosci 24: 10022–10034, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanwick RS, Pristera A, Okuse K. The trafficking of NaV1.8 Neurosci Lett 486: 78–83, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Kikuchi S, Dai Y, Kobayashi K, Fukuoka T, Noguchi K. Expression of auxiliary β subunits of sodium channels in primary afferent neurons and the effect of nerve injury. Neuroscience 121: 441–450, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaragavan K, O'Leary ME, Chahine M. Gating properties of Nav1.7 and Nav1.8 peripheral nerve sodium channels. J Neurosci 21: 7909–7918, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaragavan K, Powell AJ, Kinghorn IJ, Chahine M. Role of auxiliary β1-, β2-, and β3-subunits and their interaction with Nav1.8 voltage-gated sodium channel. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 319: 531–540, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu FH, Westenbroek RE, Silos-Santiago I, McCormick KA, Lawson D, Ge P, Ferriera H, Lilly J, Distefano PS, Catterall WA, Scheuer T, Curtis R. Sodium channel β4, a new disulfide-linked auxiliary subunit with similarity to β2. J Neurosci 23: 7577–7585, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZN, Li Q, Liu C, Wang HB, Wang Q, Bao L. The voltage-gated Na+ channel Nav1.8 contains an ER-retention/retrieval signal antagonized by the β3 subunit. J Cell Sci 121: 3243–3252, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Ziane R, Chatelier A, O'Leary ME, Chahine M. Lidocaine promotes the trafficking and functional expression of Nav1.8 sodium channels in mammalian cells. J Neurophysiol 98: 467–477, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer T, Benndorf K. The human heart and rat brain IIA Na+ channels interact with different molecular regions of the β1 subunit. J Gen Physiol 120: 887–895, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]