Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most fatal cancers due to delayed diagnosis and lack of effective treatment options. Significant exposure to Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), a potent hepatotoxic and hepatocarcinogenic mycotoxin, plays a major role in liver carcinogenesis through oxidative tissue damage and p53 mutation. The present study emphasizes the anticarcinogenic effect of Tridham (TD), a polyherbal traditional medicine, on AFB1-induced HCC in male Wistar rats. AFB1-administered HCC-bearing rats (Group II) showed increased levels of lipid peroxides (LPOs), thiobarbituric acid substances (TBARs), and protein carbonyls (PCOs) and decreased levels of enzymic and nonenzymic antioxidants when compared to control animals (Group I). Administration of TD orally (300 mg/kg body weight/day) for 45 days to HCC-bearing animals (Group III) significantly reduced the tissue damage accompanied by restoration of the levels of antioxidants. Histological observation confirmed the induction of tumour in Group II animals and complete regression of tumour in Group III animals. This study highlights the potent antioxidant properties of TD which contribute to its therapeutic effect in AFB1-induced HCC in rats.

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of primary liver cancer and accounts for around 70% of all liver cancers [1]. Various factors have been implicated as risk factors in the pathogenesis of liver cancer, notably food contaminated with aflatoxins, toxins produced by fungi of the genus Aspergillus sp. (A. flavus and A. parasiticus) [2, 3]. However, oxidative stress has emerged as a key player in the development and the progression of liver cirrhosis [4] which is known to be a precursor of HCC. Both hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) appear to be particularly more potent in inducing oxidative stress, suggesting unique mechanisms that are activated by these viral infections. AFB1 acts as a strong hepatotoxicant, mutagen and naturally occurring hepatocarcinogen, which cause liver cancer in a dose-dependent manner [5]. AFB1 is metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes to aflatoxin-8,9 epoxide which is then detoxified by the glutathione S- transferase system (GST). This reactive metabolite escapes from the detoxification process and usually conjugates with DNA nucleotides forming adducts [6]. Such adducts are responsible for the generation of observable AFB1 inducible lethal mutation. AFB1 induces lipid peroxidation in rat liver, and this may be an underlying mechanism of carcinogenesis [7]. G to T transversion mutations in codon 249 of the p53 tumour-suppressor gene have been found in human liver tumour from geographic areas with high risk of aflatoxin exposure and in AFB1-induced liver toxicity [8].

Free radicals can be defined as molecules or molecular fragments containing one or more unpaired electrons in atomic or molecular orbitals formed during a variety of biochemical reactions and cellular functions. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are free radicals of reactive anions formed by the incomplete one-electron reduction of oxygen including singlet oxygen; superoxides; peroxides; hydroxyl radicals [9]. ROS have been incriminated in the pathophysiology of a large number of diseases including coronary heart disease, neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer's disease, ageing, and cancer [10–12]. Oxidative damage/stress results when the level of ROS overpowers the system's ability to neutralize and eliminate them. Increased level of ROS usually results from lack or functional disturbance in antioxidant molecules or due to overproduction of ROS from the surrounding environment [13]. Recent studies show that ROS also have a role in cell signaling, including apoptosis, gene expression and the activation of cell signaling cascades [14].

Free radicals can cause damage in structural and metabolic components like lipids, proteins, enzymes, carbohydrates and DNA in cells and tissues. This ultimately results in membrane damage, fragmentation, or random cross-linking of molecules like DNA, enzymes, and structural proteins and even lead to cell death induced by DNA fragmentation, lipid peroxidation and finally to cancer formation [15]. Aerobic organisms have well-developed mechanisms to efficiently neutralize the oxidative effects of oxygen and its reactive metabolites. These self-sustained protective components are classified as the “antioxidant defense system” The sensitive balance between prooxidant and antioxidant forces in the body appears to be crucial in determining the state of health and well-being [16]. Under normal conditions, there is a balance between both the activities and the intracellular levels of these antioxidants. This balance is essential for the survival of organisms and their health [17]. Cumulative effect of the antioxidant defense system effectively removes the excess levels of prooxidants keeping the pro- to antioxidant ratio in an equilibrium state. Any loss in the functional activity of the major antioxidants leads to disruption in the prooxidant to antioxidant ratio, creating oxidative stress, and then cell damage ultimately favoring the process of carcinogenesis [18]. When the antioxidant system fails to counteract the increased productivity of ROS during pathological conditions, it results in oxidative stress and this is a preliminary event in the cancer initiation [13]. Supplementation of antioxidant rich diet is often recommended as part of cancer prevention [19]. There is a well-documented association between increased consumption of antioxidants and decreased incidence of cancer [20].

Tridham (TD) is a polyherbal formulation of three ingredients, Terminalia chebula seed coat, Elaeocarpus ganitrus fruits, and Prosopis cineraria leaves in equal proportion routinely used by the traditional Indian medicinal practitioners in the treatment of cancer. Terminalia chebula is a multipurpose herbal with excellent antibacterial [21], antifungal, antiviral [22], anticarcinogenic [23], antianaphylactic [24], antidiabetic [25], and antioxidant [26] properties. Elaeocarpus ganitrus commonly known as Rudraksha in India is grown in Assam and the Himalayan regions of India for medicinal properties [27]. It has excellent free radical scavenging effect in rats [28]. Besides, it is reported to exhibit multifarious pharmacological activities that include anti-inflammatory [29], analgesic, sedative [30], antidepressant, antiasthmatic [31], hypoglycemic [32], antihypertensive [33], and smooth muscle relaxant [34]. Prosopis cineraria (Syn. P. spicigera L.) possesses antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, and several other pharmacological properties [35]. The smoke of the leaves is considered good for eye ailments. Leaves of P. cineraria are rich in phytochemical constituents like alkaloids, namely, spicigerine; steroids, namely, campesterol, cholesterol, sitosterol, stigmasterol; alcohols namely octacosanol and triacontan-1-ol; and alkane hentriacontane [36].

The qualitative chemical exposition studies (data not shown) on TD showed the presence of various beneficial phytochemicals such as flavonoids, tannins, alkaloids, and polyphenols. A known compound 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid (Gallic acid) has been isolated through column chromatography and elucidated by a series of experiments, involving NMR, IR, MS, and single-crystal X-ray crystallography (XRD)(unpublished data). The isolated Gallic acid is a well known polyhydroxyphenolic compound that can be found in various natural products.

Despite innumerable studies indicating the utility of individual medicinal herbs in the treatment of various clinical manifestations, their application in cancer management is still in its initial phase. With innumerable clinically relevant active principles enriched in each component, TD is a herbal preparation with promise in combating the progression of cancer. The present study is aimed at evaluating the antioxidant potential of TD in overcoming oxidative damages associated with AFB1-instigated HCC in male Wistar albino rats.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Animals and Diet

Male albino rats of Wistar strain, 8–10 weeks of age (120–150 g), were used in this study. The animals were obtained from Central Animal House Facility, Dr. ALM PG IBMS, University of Madras, Taramani, Chennai, India. The animals were housed in polypropylene cages under a controlled environment with 12 ± 1 h light/dark cycles and a temperature between 27 and 37°C and were fed with standard pellet diet (Gold Mohor rat feed, M/s. Hindustan Lever Ltd., Mumbai) and water ad libitum. All experiments involving animals were conducted according to NIH guidelines, after obtaining approval from the institute's animal ethical committee (IAEC no. 06/012/08).

2.1.2. Chemicals

AFB1 was procured from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO. It was dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) immediately before administration. All other chemicals used were of highest purity and analytical grade.

2.1.3. TD Preparation and Dose Determination

TD drug is a combination of Terminalia chebula seed coats (family: Combretaceae), dry seeds of Elaeocarpus ganitrus (Syn. E. sphaericus) (family: Elaeocarpaceae) and Prosopis cineraria leaves (Syn. P. spicigera L.) (family: Leguminosae). The three ingredients were collected and given to the Department of Centre for Advance Study (CAS) in Botany, University of Madras, Guindy Campus, Chennai, India for botanical authentication. The assigned herbarium numbers are CASBH-16: Terminalia chebula, CASBH-17: Elaeocarpus ganitrus, CASBH-18: Prosopis cineraria. The Ingredients were washed, air-dried in shade, and then finely ground. The components were then mixed in equal proportions on weight basis to get TD mixture. The extract of TD was prepared in 3 : 1 (v/w) ratio by adding 30 mL of water to 10 grams of combined TD and mixed well. The mixture was mixed by using a shaker for 12 hours. The mixture was subsequently filtered using filter paper, and the clear filtrate (aqueous extract) was collected in a beaker. The filtrate was then lyophilized under vacuum pressure to yield a powder. The lyophilized extract was stored in airtight containers in a dry dark place.

The dose of TD used, that is, 300 mg/kg body weight/day, was decided upon after carrying out a dose-dependent study. Acute toxicity studies showed no mortality and sub-acute toxicity studies showed no significant changes in histopathological, hematological, and biochemical parameters. Based on these studies, we carried out a dose-dependent study at doses of 50, 100, 200, 300, 400 mg/kg body weight/day. The results of this study revealed that the lowest possible effective dose was 300 mg/kg body weight as evidenced by histopathological observations, a significant (P < 0.05) increase in body weight and a significant (P < 0.05) reduction in the levels of marker enzymes in serum and liver (Unpublished data). The duration of treatment, that is, 45 days is the duration used by Siddha (a traditional Indian system of medicine) physicians for treating HCC patients utilizing the formulation TD. Thus the optimum dose of TD was found to be 300 mg/kg body weight/day for 45 days, and this dose was used for all the subsequent experiments.

2.1.4. Experimental Design

Animals were divided into following four groups of six animals each. AFB1 was freshly prepared by dissolving in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) before administration.

Group I. Normal control animals

Group II. HCC was induced in these animals by a single intra-peritoneal dose of AFB1 (2 mg/kg body weight) [37].

Group III. HCC-induced animals (as in Group II) were administered with the drug, TD (300 mg/kg body weight/day) orally for 45 days.

Group IV. Drug control animals received the same dosage of TD as in Group III animals.

On the completion of the experimental period, animals were sacrificed by cervical decapitation between 8:00 and 10:00 h to avoid any possible rhythmic variations in the antioxidant enzyme level. Blood was collected. Liver and kidney were simultaneously removed, washed with ice-cold saline. The organs were weighed, and one portion of each of these organs was fixed in 10% formalin for histopathological examinations. 10% homogenate was prepared with fresh tissue in 0.01 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4). The resultant supernatant was then used for biochemical assays.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Biochemical Investigations

Total protein was estimated by the method of Lowry et al. [38] using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard. LPO was measured by the method of Devesagayam and Tarachand [39]. The TBARs were estimated as per the spectrophotometric method described by Ohkawa et al. [40]. PCOs were measured by the method of Reznick and Packer [41]. SOD was assayed by the method of Marklund and Marklund [42]. CAT was assayed by the method of Sinha [43]. Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) was assayed by the method of Rotruck et al. [44]. GSH was determined by the method of Moron et al. [45]. Vitamin E was estimated by the method of Quaife and Dju [46]. Vitamin C was estimated by the method of Omaye et al. [47].

2.2.2. Statistical Analysis

The values are expressed as mean ± SD for six rats in each group. Statistically significant differences between the groups were calculated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) employing statistical package for social sciences (SPSS). Values of P < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

2.2.3. Gross Morphology and Histopathological Studies

Portions of tissues were then fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, routinely processed, and embedded in paraffin wax. Consecutive sections were cut at a thickness of 3-4 μm and subsequently stained with hematoxylin and eosin [48].

3. Results

3.1. Macromolecular Damage

Tables 1 and 2 depict the levels of LPO, TBARs, and PCO in liver and kidney of control and experimental animals. There was a significant increase in LPO, TBARs, and PCO in the HCC-induced (Group II) animals. The levels of these parameters were restored to near-normal levels on treatment with TD in Group III animals.

Table 1.

Effect of TD on indicators of macromolecular damage in liver of control and experimental animals.

| Parameters | Group I (control) | Group II (AFB1 induced) | Group III (AFB1 induced + TD) | Group IV (TD alone) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid peroxides (LPO) | 51.64 ± 5.62 | 79.41 ± 9.26a∗ | 53.15 ± 6.14b∗ | 50.44 ± 5.02cNS |

| Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARSs) | 3.89 ± 0.41 | 7.74 ± 0.73a∗ | 4.25 ± 0.49b∗ | 3.93 ± 0.38cNS |

| Protein carbonyls (PCOs) | 6.13 ± 0.57 | 14.75 ± 1.78a∗ | 8.31 ± 0.89b∗ | 5.96 ± 0.64cNS |

Units. LPO: nmoles of MDA formed/mg protein, TBARS: nmoles/100 g tissue, protein carbonyl: nmoles of DNPH formed/min/mg protein. Values are expressed as mean ± SD for six animals. Comparisons are made between “a” Group II versus Group I, “b” Group III versus Group II, “c” Group IV versus Group I. The symbol *represents the statistical significance at P < 0.05. NS: nonsignificant.

Table 2.

Effect TD on indicators of macromolecular damage in kidney of control and experimental animals.

| Parameters | Group I (control) | Group II (AFB1 induced) | Group III (AFB1 induced + TD) | Group V (TD alone) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid peroxides (LPO) | 46.87 ± 3.62 | 68.17 ± 6.38a∗ | 48.53 ± 5.21b∗ | 45.87 ± 4.76cNS |

| Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARSs) | 3.13 ± 0.37 | 7.39 ± 0.69a∗ | 3.95 ± 0.44b∗ | 3.18 ± 0.35cNS |

| Protein carbonyls (PCOs) | 5.53 ± 0.59 | 11.61 ± 1.31a∗ | 6.14 ± 0.69b∗ | 5.56 ± 0.61cNS |

Units: LPO: nmoles of MDA formed/mg protein, TBARS: nmoles/100 g tissue, protein carbonyl: nmoles of DNPH formed/min/mg protein. Values are expressed as mean ± SD for six animals. Comparisons are made between “a” Group II versus Group I, “b” Group III versus Group II, “c” Group IV versus Group I. The symbol *represents the statistical significance at P < 0.05. NS: nonsignificant.

3.2. Antioxidants

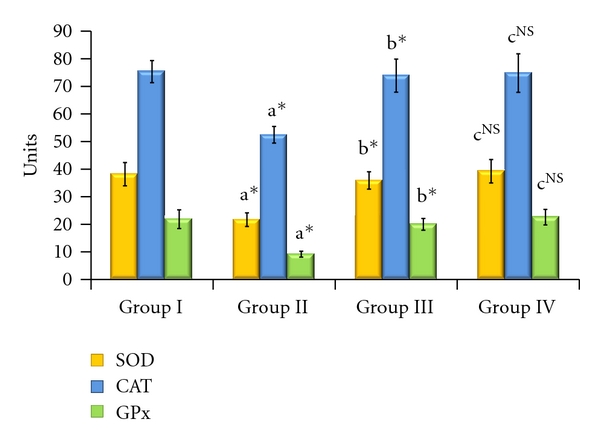

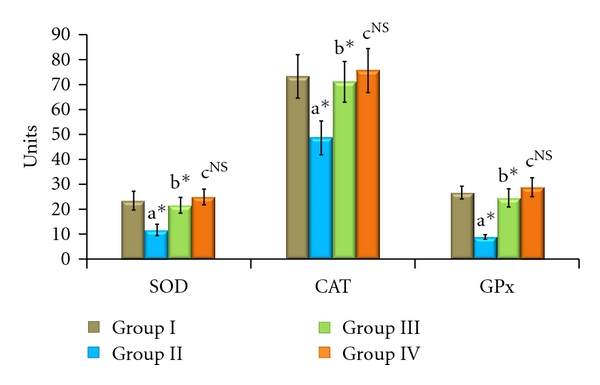

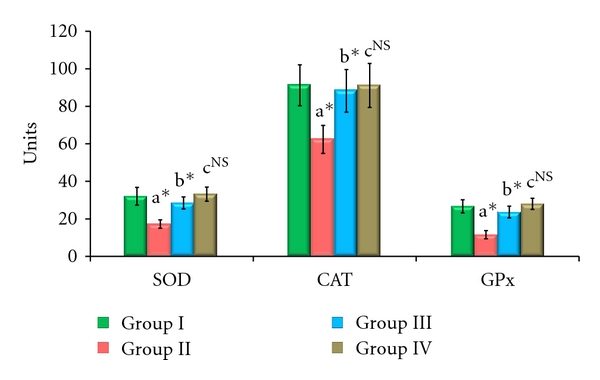

The enzymic antioxidant activities of SOD, CAT, and GPx in the serum, liver, and kidney are shown in Figures 1, 2, and 3, respectively. From these figures, it is evident that the activities of enzymic antioxidants were significantly decreased in AFB1-induced animals (Group II). HCC bearing animals receiving TD treatment (Group III) attained a near-normal level of enzymic antioxidant activities. The levels of antioxidant enzymes remained constant without showing any significant change in Group IV drug control animals.

Figure 1.

Effect of TD on enzymic antioxidants in serum of control and experimental animals. Values are expressed as mean ± SD for six animals. Comparisons are made between “a” Group II versus Group I, “b” Group III versus Group II, “c” Group IV versus Group I. The symbol *represents the statistical significance at P < 0.05 NS: nonsignificant. SOD: U/min/mg protein, CAT: μmoles of H2O2 consumed/min/mg protein, GPx: μmoles of GSH oxidized/min/mg protein.

Figure 2.

Effect of TD on enzymic antioxidants in liver of control and experimental animals. Values are expressed as mean ± SD for six animals. Comparisons are made between “a” Group II versus Group I, “b” Group III versus Group II, “c” Group IV versus Group I. The symbol *represents the statistical significance at P < 0.05. NS: nonsignificant. SOD: U/min/mg protein, CAT: μmoles of H2O2 consumed/min/mg protein, GPx: μmoles of GSH oxidized/min/mg protein.

Figure 3.

Effect of TD on enzymic antioxidants in kidney of control and experimental animals. Values are expressed as mean ± SD for six animals. Comparisons are made between “a” Group II versus Group I, “b” Group III versus Group II, “c” Group IV versus Group I. The symbol *represents the statistical significance at P < 0.05. NS: nonsignificant. SOD: U/min/mg protein, CAT: μmoles of H2O2 consumed/min/mg protein, GPx: μmoles of GSH oxidized/min/mg protein.

The levels of nonenzymic antioxidants like vitamin C, vitamin E, GSH, total thiols (TTs), and nonprotein thiols (NPT) in the serum, liver, and kidney are depicted in Tables 3, 4, and 5. Similar to enzymic antioxidant status, the levels of non-enzymic antioxidants were also decreased significantly in HCC animals (Group II), which were reverted to near-normal levels after treatment with TD in Group III animals. No significant variation in the level of non-enzymic antioxidants was noted in Group IV drug control animals.

Table 3.

Effect of TD on non enzymic antioxidants and thiols in serum of control and experimental animals.

| Parameters | Group I (control) | Group II (AFB1 induced) | Group III (AFB1 induced + TD) | Group IV (TD alone) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C | 2.83 ± 0.29 | 0.99 ± 0.01a∗ | 2.87 ± 0.28b∗ | 2.85 ± 0.31cNS |

| Vitamin E | 2.43 ± 0.28 | 1.09 ± 0.19a∗ | 2.38 ± 0.27b∗ | 2.45 ± 0.26cNS |

| Total thiols (TSHs) | 5.16 ± 0.59 | 3.07 ± 0.39a∗ | 5.09 ± 0.51b∗ | 5.17 ± 0.53cNS |

| Non protein thiols (NPSHs) | 4.89 ± 0.51 | 1.69 ± 0.19a∗ | 4.66 ± 0.51b∗ | 4.97 ± 0.52cNS |

| Reduced glutathione (GSH) | 24.68 ± 2.92 | 9.45 ± 1.67a∗ | 23.35 ± 3.16b∗ | 24.63 ± 2.67cNS |

Units: GSH mg/100 g tissue, Vitamins C and E mg/dL tissue, TSH and NPSH: μg/mg protein. Values are expressed as mean ± SD for six animals. Comparisons are made between “a” Group II versus Group I, “b” Group III versus Group II, “c” Group IV versus Group I. The symbol *represents the statistical significance at P < 0.05. NS: nonsignificant.

Table 4.

Effect of TD on nonenzymic antioxidants and thiols in liver of control and experimental animals.

| Parameters | Group I (control) | Group II (AFB1 induced) | Group III (AFB1 induced + TD) | Group IV (TD alone) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C | 3.93 ± 0.49 | 1.95 ± 0.27a∗ | 3.69 ± 0.43b∗ | 4.11 ± 0.51cNS |

| Vitamin E | 2.54 ± 0.35 | 1.36 ± 0.17a∗ | 2.38 ± 0.28b∗ | 2.45 ± 0.31cNS |

| Total thiols (TSHs) | 9.42 ± 1.13 | 4.68 ± 0.56a∗ | 8.81 ± 1.14b∗ | 9.31 ± 1.11cNS |

| Non protein thiols (NPSHs) | 5.58 ± 0.66 | 2.15 ± 0.25a∗ | 5.31 ± 0.68b∗ | 5.44 ± 0.65cNS |

| Reduced glutathione (GSH) | 32.31 ± 4.21 | 18.34 ± 2.77a∗ | 29.73 ± 4.75b∗ | 33.83 ± 4.17cNS |

Units: GSH mg/100 g tissue, Vitamin C and E mg/g wet tissue, TSH and NPSH: μg/mg protein. Values are expressed as mean ± SD for six animals. Comparisons are made between “a” Group II versus Group I, “b” Group III versus Group II, “c” Group IV versus Group I. The symbol *represents the statistical significance at P < 0.05. NS: nonsignificant.

Table 5.

Effect of TD on nonenzymic antioxidants and thiols in kidney of control and experimental animals.

| Parameters | Group I (control) | Group II (AFB1 induced) | Group III (AFB1 induced + TD) | Group IV (TD alone) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C | 2.94 ± 0.38 | 1.52 ± 0.22a∗ | 2.78 ± 0.35b∗ | 2.95 ± 0.37cNS |

| Vitamin E | 2.85 ± 0.29 | 1.12 ± 0.17a∗ | 2.42 ± 0.27b∗ | 2.91 ± 0.31cNS |

| Total thiols (TSH) | 7.17 ± 1.14 | 2.88 ± 0.33a∗ | 6.85 ± 0.78b∗ | 7.79 ± 0.81cNS |

| Non protein thiols (NPSH) | 4.75 ± 0.61 | 2.68 ± 0.34a∗ | 4.31 ± 0.51b∗ | 4.68 ± 0.56cNS |

| Reduced glutathione (GSH) | 27.04 ± 2.97 | 13.54 ± 2.21a∗ | 25.51 ± 2.98b∗ | 27.98 ± 3.23cNS |

Units-GSH-mg/100 g tissue, Vitamin C and E-mg/g wet tissue, TSH and NPSH: μg/mg protein. Values are expressed as mean ± SD for six animals. Comparisons are made between “a” Group II versus Group I, “b” Group III versus Group II, “c” Group IV versus Group I. The symbol *represents the statistical significance at P < 0.05. NS: nonsignificant.

3.3. Gross Morphology and Histopathology

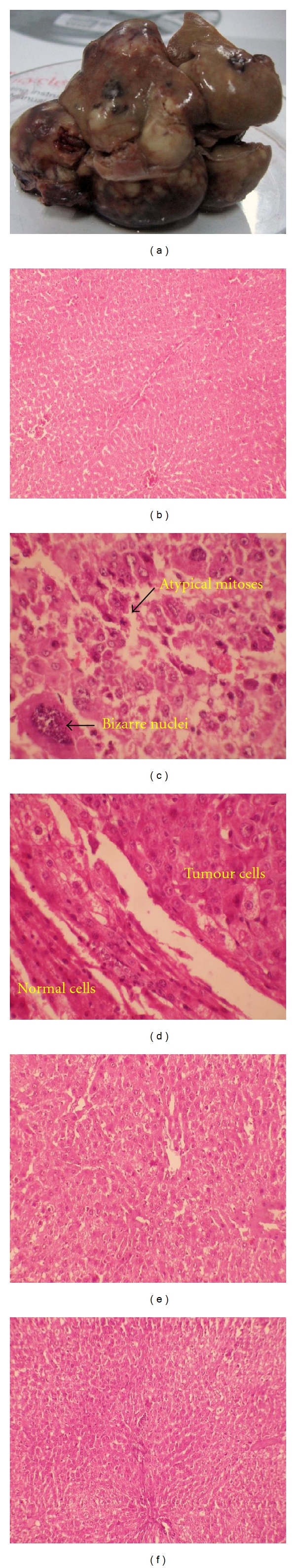

Grossly, liver tissue of Group II animals (AFB1 induced) showed whitish nodular tumours of varying sizes in the liver (Figure 4(a)).

Figure 4.

Effect of TD on gross morphology and histopathology in liver of control and experimental animals. (a) Gross morphology of Group II animals (AFB1 induced). (b) Liver tissue of Group I control animals (10X). (c) Liver tissue of Group II (AFB1 induced) animals (40X). (d) Liver tissue of Group II (AFB1 induced) animals (40X). (e) Liver tissue of Group III (AFB1 induced + TD treated) animals (10X). (f) Liver tissue of Group IV (TD treated) animals (10X).

Microscopically, Group I control animals showed liver tissue with normal histology (Figure 4(b)). The liver of Group II (AFB1 induced) animals was infiltrated by hyperchromatic pleomorphic tumour cells arranged in a trabecular pattern in some areas and in sheets and nests in other areas. Numerous mitotic figures including atypical mitoses were seen. Some of the tumour cells showed markedly enlarged, bizarre nuclei (Figure 4(c)). The adjacent normal liver cells showed nodularity and dysplastic features (Figure 4(d)). Group III (AFB1 induced TD treated) liver showed normal histology. There was no evidence of tumour (Figure 4(e)). Group V (TD alone) liver showed normal morphology and architecture (Figure 4(f)).

4. Discussion

LPO is a well-recognized preliminary event of oxidative damage of plasma membrane and initiation of carcinogenesis [49]. The formation of the metabolite, AFB1-8,9-epoxide, causes membrane damage through lipid peroxidation and subsequent covalent binding to DNA to form AFB1-DNA adducts. These are critical steps leading to hepatocarcinogenesis [50]. There was a significant reduction in the level of lipid peroxides upon treatment with TD in tumour-bearing animals which have been mainly attributed to the components of TD. Aqueous extract of T. chebula at a concentration of 15 μg/mL shows 50% inhibition in LPO activity [51]. A report by Suchalatha and Devi [52] strongly indicate a protective role of T. chebula against membrane damage by prevention of peroxide radical formation and MDA formation in isoproterenol-induced oxidative stress in rats. E. ganitrus acts as a potent iron chelator with 76.70% inhibition at a concentration of 500 μg/mL. Metal chelating agents reduce the concentration of catalyzing transition metals by forming sigma bonds and reducing the redox potential, thereby stabilizing the oxidized form of the metal ion [53]. Malon dialdehyde acts as an important contributor to the increase in protein carbonyl content observed during the oxidation of protein/polyunsaturated fatty acid mixtures [54]. Dietary antioxidant and polyphenols act against ROS thereby indirectly reducing the PCO content [55]. The inhibitory effects of PCO by TD may be attributed to the presence of various bioactive components such as flavonoids, alkaloids, and polyphenols that act as antioxidants by scavenging chain-propagating, reactive free radicals generated by AFB1.

The reducing capacity of a compound serves as a significant indicator of its potential antioxidant activity. Levels of enzymic antioxidants were significantly decreased in HCC-bearing animals as these are consumed for reducing prooxidants. Supplementation of TD to tumour-bearing animals restored the level of different antioxidants, effectively. Flavonoids have been shown to act as scavengers of various oxidizing species, such as hydroxyl radicals, peroxy radicals, or superoxide anions, due to the presence of a catechol group in the B-ring and the 2,3 double bond in conjunction with the 4-carbonyl group as well as the 3- and 5-hydroxyl groups [56, 57]. Flavonoids have been proved to be potent inhibitors of enhanced spontaneous production of both MDA and conjugated dienes [58]. Antioxidant activity of TD results mainly from ellagic acid, 2,4-chebulyl-b-D-glucopyranose, chebulinic acid, casuarinin, chelani, and 1,6-di-O-galloyl-b-D-glucose which have been reported to be active constituents in T. chebula fruits [23, 26]. Aqueous extract of fruit of T. chebula should strengthen antioxidant properties, presenting tert-butyl hydroperoxide- (t-BHP-) induced oxidative injury observed in cultured rat primary hepatocytes and rat liver [59]. Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) is considered as a major defence against peroxides, superoxide anion, and hydrogen peroxide and assumes an important role in detoxifying lipid and hydrogen peroxide with the concomitant oxidation of glutathione [60]. Phytochemicals present in T. chebula may contribute to restoration of GPx activity by TD treatment observed in this study. These antioxidant activities of TD are based on hydrogen donation abilities and chelating metal ions.

GSH plays a major role in the detoxification of xenobiotic compounds [61]. The high levels of flavonoids and phenolic compounds present in components of TD have been reported to have the capacity to increase GSH levels, modifying its redox rate and actively, participating in the eliminating of AFB1 metabolite [62]. Sharma et al. [63] have reported that phenolic compounds are found to be inducers of GSH. Gallic acid, a polyphenol, is one of the hepatoprotective active principles isolated from TD that may augment GSH levels. Vitamin C is one of the most effective biological antioxidants, and it has been shown that vitamin C supplementation can reduce risks of diseases associated with oxidative stress, such as cancer [64]. Among the factors modifying oxidative stress, there is strong interest in the antioxidant vitamins E and C, the intake of which can be easily and safely controlled through the diet. Vitamin C protects cells mainly against ROS such as superoxide anion radical, hydroxyl oxygen radical, hydrogen peroxide, and singlet oxygen [65]. It is the most significant antioxidant that can protect against carcinogenesis and tumour growth. A decreased level of vitamin E content might be due to the excessive utilization of this antioxidant for quenching the enormous quantity of free radicals produced in these conditions. According to Hazra et al. [66] T. chebula is known for its natural antioxidant property due to its content of vitamins C. Thus, vitamin C and E could act synergistically in scavenging a wide variety of ROS. Thiols are water-soluble antioxidants linked to membrane proteins and are essential for the antioxidant system. AFB1 administration causes the reduction of thiol levels [67]. Both total and nonprotein thiols were decreased in AFB1-induced HCC conditions. Due to the antioxidant and free radical quenching nature of TD, the thiol levels were resumed to near normal in drug-treated animals. TD acts as potential antioxidant agent by exerting its activity at various levels to reduce AFB1-induced oxidative stress and effectively quenches free radicals, reduces its formation, and increases the activity of different antioxidant enzymes. Thus TD has a hepatoprotective effect as demonstrated by enhanced activity of antioxidant enzymes. The redeeming action of TD in tumour-induced rats is most probably due to additive and synergistic effect of individual components.

Compounds such as tannins are reported to be responsible for retrieval of vitamin C activity [68], whereas trigalloyl glucose and ellagic acid [69] present in TD might strengthen the soothing activity of the drug. We have evaluated the antioxidant potential of TD by studying the combined effects of three ingredients derived from T. chebula, E. ganitrus and P. cineraria in AFB1-induced liver cancer. The active principles present in each component render TD a potent antioxidant property. The therapeutic effect of TD in tumour-induced rats is most probably due to the synergistic action of the constituents such as flavonoids, alkaloids and tannins. T. chebula contains the flavonoids, gallic acid, 1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-galloyl-b-D-glucopyranose, chebulagic acid and chebulinic acid as well as vitamin C [70]. A report from Ray et al. [71] reveals the presence of alkaloids, glycosides, steroids, and flavonoids in E. ganitrus. Malik and Kalidhar [36] have reported the presence of tannins, alkaloids and steroids in Prosopis cineraria leaves. Thus TD has been found to exhibit hepatoprotective and anticarcinogenic effect as demonstrated by increased activity of antioxidant enzymes and total regression of tumour seen on histopathological examination of the liver. In summary, the present study provides the evidence that TD has therapeutic effect in AFB1-induced HCC. TD also reverses the free radical damage brought about by administration of AFB1 by enhancing the enzymatic and non enzymatic antioxidant defense mechanisms.

5. Conclusion

The protection by TD against oxidative stress in AFB1-mediated HCC might has occurred through multiple actions, which include prevention of LPO and stabilization of antioxidant defense mechanism. These factors protect cells from ROS damage in AFB1-induced HCC, as TD abolishes the causative factors of liver injury and tumour markers by decreasing LPO, the possible mechanism of AFB1 induction. The strong antioxidant and therapeutic effect of TD in vivo might be due to the spectrum of synergistically active phytomolecules present in TD. Elucidation of the exact mechanism of action of the phytotherapeutic effect of TD in AFB1-induced HCC necessitates further studies.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests to disclose.

Acknowledgment

One of the authors, Mr. Jaganathan Ravindran, acknowledges the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, India for the financial assistance given in the form of Senior Research Fellowship (no. 3/2/2/189/2009/NCD-III).

References

- 1.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Novel advancements in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma in 2008. Journal of Hepatology. 2008;48(1):S20–S37. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krishnan S, Manavathu EK, Chandrasekar PH. Aspergillus flavus: an emerging non-fumigatus Aspergillus species of significance. Mycoses. 2009;52(3):206–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nigam SK, Ghosh SK, Malaviya R. Aflatoxin, its metabolism and carcinogenesis—a historical review. Toxin Reviews. 1994;13(2):179–203. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi BG, Park SH, Byun JY, Jung SE, Choi KH, Han JY. The findings of ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma on helical CT. British Journal of Radiology. 2001;74(878):142–146. doi: 10.1259/bjr.74.878.740142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzman PD. Exposure to aflatoxin B1 in experimental animals and its public health significance. Salud Publica de Mexico. 2007;49(3):227–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Essigmann JM, Croy RG, Bennett RA, Wogan GN. Metabolic activation of aflatoxin B1: patterns of DNA adduct formation, removal, and excretion in relation to carcinogenesis. Drug Metabolism Reviews. 1982;13(4):581–602. doi: 10.3109/03602538209011088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen HM, Shi CY, Shen Y, Ong CN. Detection of elevated reactive oxygen species level in cultured rat hepatocytes treated with aflatoxin B1. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1996;21(2):139–146. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Staib F, Hussain SP, Hofseth LJ, Wang XW, Harris CC. TP53 and liver carcinogenesis. Human Mutation. 2003;21(3):201–216. doi: 10.1002/humu.10176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. 3rd edition. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90(17):7915–7922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith MA, Perry G, Richey PL, et al. Oxidative damage in Alzheimer’s [6] Nature. 1996;382(6587):120–121. doi: 10.1038/382120b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinbrenner T, Cladellas M, Covas MI, et al. High oxidative stress in patients with stable coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 2003;168(1):99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sohal RS, Weindruch R. Oxidative stress, caloric restriction, and aging. Science. 1996;273(5271):59–63. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hancock JT, Desikan R, Neill SJ. Role of reactive oxygen species in cell signalling pathways. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2001;29, part 2:345–350. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beckman KB, Ames BN. The free radical theory of aging matures. Physiological Reviews. 1998;78(2):547–581. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.2.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pryor WA. Oxy-radicals and related species: their formation, lifetimes, and reactions. Annual Review of Physiology. 1986;48:657–667. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.48.030186.003301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MTD, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2007;39(1):44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutteridge JMC. Biological origin of free radicals and mechanisms of antioxidant protection. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 1994;91(2-3):133–140. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeisel SH. Antioxidants suppress apoptosis. Free radicals: the pros and cons of antioxidants. Journal of Nutrition. 2004;134(11):3179S–3180S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.11.3179S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seifried HE, McDonald SS, Anderson DE, Greenwald P, Milner JA. The antioxidant conundrum in cancer. Cancer Research. 2003;63(15):4295–4298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malekzadeh F, Ehsanifar H, Shahamat M, Levin M, Colwell RR. Antibacterial activity of black myrobalan (Terminalia chebula retz) against Helicobacter pylori. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2001;18(1):85–88. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(01)00352-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yukawa TA, Kurokawa M, Sato H, et al. Prophylactic treatment of cytomegalovirus infection with traditional herbs. Antiviral Research. 1996;32(2):63–70. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(95)00978-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saleem A, Husheem M, Harkonen P, Pihlaja K. Inhibition of cancer cell growth by crude extract and the phenolics of Terminalia chebula retz. fruit. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2002;81(3):327–336. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chattopadhyay RR, Bhattacharyya SK. Plant review, Terminalia chebula: an update. Pharmacognosy Reviews. 2007;1(1):151–156. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabu MC, Kuttan R. Anti-diabetic activity of medicinal plants and its relationship with their antioxidant property. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2002;81(2):155–160. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng HY, Lin TC, Yu KH, Yang CM, Lin CC. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities of Terminalia chebula . Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2003;26(9):1331–1335. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asolkar LV, Kakkar KK, Chakre OJ. Second Supplement toGglossary of Indian Medicinal Plants with Active Principles, Part I (A-K) (1965–1981) Vol. 289. New Delhi, India: PID & CSIR; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh RK, Acharya SB, Bhattacharya SK. Pharmacological activity of Elaeocarpus sphaericus . Phytotherapy Research. 2000;14(1):36–39. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1573(200002)14:1<36::aid-ptr541>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh RK, Pandey BL. Anti-inflammatory activity of Elaeocarpus sphaericus fruit extract in rats. Journal of Medicinal and Aromatic Plant Sciences. 1999;21:1030–1032. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katavic PL, Venables DA, Rali T, Carroll AR. Indolizidine alkaloids with delta-opioid receptor binding affinity from the leaves of Elaeocarpus fuscoides . Journal of Natural Products. 2007;70(5):872–875. doi: 10.1021/np060607e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh RK, Bhattacharya SK, Acharya SB. Studies on extracts of Elaeocarpus sphaericus fruits on in vitro rat mast cells. Phytomedicine. 2000;7(3):205–207. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(00)80005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Satyavati GV, Raina MK, Sharma M. Medicinal Plants of India. New Delhi, India: Indian Council of Medical Research; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarkar PK, Sengupta SS, Bhattacharya SS. Further observations with Elaeocarpus ganitrus on normal and hypodynamic hearts. Indian Journal of Pharmacy. 1973;5:252–258. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhattacharya SK, Debnath PK, Pandey VB, Sanyal AK. Pharmacological investigations on Elaeocarpus ganitrus . Planta Medica. 1975;28(2):174–177. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1097848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chopra RN, Nayar SL, Chopra IC. Glossary of Indian Medicinal Plants. Vol. 204. New Delhi, India: Council for Scientific and Industrial Research; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malik A, Kalidhar SB. Phytochemical examination of Prosopis cineraria . Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2007;69(4):576–578. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Umarani M, Shanthi P, Sachdanandam P. Protective effect of Kalpaamruthaa in combating the oxidative stress posed by aflatoxin B1-induced hepatocellular carcinoma with special reference to flavonoid structure-activity relationship. Liver International. 2008;28(2):200–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1951;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Devesagayam TPA, Tarachand U. Decreased lipid peroxidation in the rat kidney during gestation. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1987;145(1):134–138. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)91297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Analytical Biochemistry. 1979;95(2):351–358. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reznick AZ, Packer L. Oxidative damage to proteins: spectrophotometric method for carbonyl assay. Methods in Enzymology. 1994;233:357–363. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)33041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marklund S, Marklund G. Involvement of the superoxide anion radical in the autoxidation of pyrogallol and a convenient assay for superoxide dismutase. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1974;47(3):469–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sinha AK. Colorimetric assay of catalase. Analytical Biochemistry. 1972;47(2):389–394. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rotruck JT, Pope AL, Ganther HE, Swanson AB, Hafeman DG, Hoekstra WG. Selenium: biochemical role as a component of glatathione peroxidase. Science. 1973;179(4073):588–590. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4073.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moron MS, Depierre JW, Mannervik B. Levels of glutathione, glutathione reductase and glutathione S-transferase activities in rat lung and liver. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1979;582(1):67–78. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(79)90289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quaife ML, M. Y. Dju. Chemical estimation of vitamin E in tissue and the tocopherol content of some normal human tissues. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1949;180(1):263–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Omaye ST, Turnbull JD, Sauberlich HE. Selected methods for the determination of ascorbic acid in animal cells, tissues, and fluids. Methods in Enzymology. 1979;62:3–11. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)62181-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Culling CFA. Handbook of Histopathological and Histochemical Techniques. 3rd edition. London, UK: Butterworth and Co.; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Banakar MC, Paramasivan SK, Chattopadhyay MB, et al. 1alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 prevents DNA damage and restores antioxidant enzymes in rat hepatocarcinogenesis induced by diethylnitrosamine and promoted by phenobarbital. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2004;10(9):1268–1275. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i9.1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guengerich FP, Cai H, McMahon M, et al. Reduction of aflatoxin B1 dialdehyde by rat and human aldo-keto reductases. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2001;14(6):727–737. doi: 10.1021/tx010005p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naik GH, Priyadarsini KI, Naik DB, Gangabhagirathi R, Mohan H. Studies on the aqueous extract of Terminalia chebula as a potent antioxidant and a probable radioprotector. Phytomedicine. 2004;11(6):530–538. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suchalatha S, Devi CSS. Protective effect of Terminalia chebula against lysosomal enzyme alterations in isoproterenol-induced cardiac damage in rats. Experimental and Clinical Cardiology. 2005;10(2):91–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumar TS, Shanmugam S, Palvannan T, Kumar VMB. Evaluation of antioxidant properties of Elaeocarpus ganitrus roxb. leaves. Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2008;7(3):211–215. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dkhar P, Sharma R. Effect of dimethylsulphoxide and curcumin on protein carbonyls and reactive oxygen species of cerebral hemispheres of mice as a function of age. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2010;28(5):351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reutrakul V, Ningnuek N, Pohmakotr M, et al. Anti HIV-1 flavonoid glycosides from Ochna integerrima. Planta Medica. 2007;73(7):683–688. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-981538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Madsen HL, Andersen CM, Jorgensen LV, Skibsted LH. Radical scavenging by dietary flavonoids. A kinetic study of antioxidant efficiencies. European Food Research and Technology. 2000;211(4):240–246. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Modak B, Contreras ML, Gonzalez-Nilo F, Torres R. Structure—antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids isolated from the resinous exudate of Heliotropium sinuatum. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2005;15(2):309–312. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Siegers CP, Younes M. Clinical significance of the glutathione-conjugating system. Pharmacological Research Communications. 1983;15(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0031-6989(83)80075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee HS, Won NH, Kim KH, Lee H, Jun W, Lee KW. Antioxidant effects of aqueous extract of Terminalia chebula in Vivo and in Vitro. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2005;28(9):1639–1644. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yin L, Huang J, Huang W, Li D, Wang G, Liu Y. Microcystin-RR-induced accumulation of reactive oxygen species and alteration of antioxidant systems in tobacco BY-2 cells. Toxicon. 2005;46(5):507–512. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Glatt H, Friedberg T, Grover PL. Inactivation of a diol-epoxide and a K-region epoxide with high efficiency by glutathione transferase X. Cancer Research. 1983;43(12 I):5713–5717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sanz MJ, Ferrandiz ML, Cejudo M, et al. Influence of a series of natural flavonoids on free radical generating systems and oxidative stress. Xenobiotica. 1994;24(7):689–699. doi: 10.3109/00498259409043270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sharma S, Stutzman JD, Kelloff GJ, Steele VE. Screening of potential chemopreventive agents using biochemical markers of carcinogenesis. Cancer Research. 1994;54(22):5848–5855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Byers T, Perry G. Dietary carotenes, vitamin C, and vitamin E as protective antioxidants in human cancers. Annual Review of Nutrition. 1992;12:139–159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.12.070192.001035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meister A. Glutathione, ascorbate, and cellular protection. Cancer Research. 1994;54(7):1969s–1975s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hazra B, Sarkar R, Biswas S, Mandal N. Comparative study of the antioxidant and reactive oxygen species scavenging properties in the extracts of the fruits of Terminalia chebula, Terminalia belerica and Emblica officinalis . BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2010;10, article 20 doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carrillo MC, Carnovale CE, Monti JA. Effect of aflatoxin B1 treatment in vivo on the in vitro activity of hepatic and extrahepatic glutathione S-transferase. Toxicology Letters. 1990;50(1):107–116. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(90)90257-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bhattacharya A, Chatterjee A, Ghosal S, Bhattacharya SK. Antioxidant activity of active tannoid principles of Emblica officinalis (amla) Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 1999;37(7):676–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang YJ, Abe T, Tanaka T, Yang CR, Kouno I. Phyllanemblinins A-F, new ellagitannins from Phyllanthus emblica. Journal of Natural Products. 2001;64(12):1527–1532. doi: 10.1021/np010370g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Surveswaran S, Cai YZ, Corke H, Sun M. Systematic evaluation of natural phenolic antioxidants from 133 Indian medicinal plants. Food Chemistry. 2007;102(3):938–953. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ray AB, Chand L, Pandey VB. Rudrakine, a new alkaloid from Elaeocarpus ganitrus . Phytochemistry. 1979;18(4):700–701. [Google Scholar]