Abstract

Ayurvedic texts describe rejuvenate measures called Rasayana to impart biological sustenance to bodily tissues. Rasayana acting specifically on brain are called Medhya Rasayana. Brahmi is one of the most commonly practiced herbs for the same. Yet there exist a controversy regarding the exact plant species among Bacopa monnieri L. Penn (BM) and Centella asiatica (L.) Urban (CA) to be used as Brahmi in the formulations. Though the current literature available has suggested a very good nootropic potential of both the drugs, none of the studies have been carried out on comparative potential of these herbs to resolve the controversy. Free-radical scavenging potential for these plants is studied to find out their comparative efficacy. The study revealed a very good in vitro free-radical scavenging properties of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of both the plants as evidenced by FRAP, DPPH, reducing power, and antilipid peroxidation assays. It can be concluded from the studies that both the plants, although taxonomically totally different at family level, showed similar type of in vitro activities. The total phenolic and flavonoid contents also revealed a significant similarity in the two plants. The in vitro study supports the Ayurvedic concept of BM and CA having a similar potential.

Keywords: Bacopa, Brahmi, Centella, free-radical scavenging antioxidants

Introduction

Plants have a longest history of use as a medicine, food source, and for a variety of daily needs.[1] Of the 250,000 known plant species on the Earth, more than 80,000 are utilized for medicinal purposes. India is one of the world's 12 biodiversity centers with the presence of over 45,000 different plant species. Of these, about 15,000-20,000 plants have a potent medicinal value. However, only 7,000-7,500 species are utilized in routine by traditional communities for their medicinal value.[2]

In India, drugs of herbal origin have been used by Ayurveda, Siddha, and Unani systems of medicines since ancient times. Among all traditional systems, Ayurveda is the most ancient yet still successfully practiced system, especially in India, Sri Lanka, Germany, China, and many other countries.[3] It has a sound philosophical and experiential basis as well as a holistic approach to cure or combat the diseases to maintain a healthy state of mind and body. The sacred texts in Ayurveda have explained several plant species for their use in various ailments. Several classical literatures like Charak Samhita and Sushrut Samhita had described properties and uses of 1,100 and 1,270 species respectively.[2] More than 8,000 herbal remedies have been codified in Ayurveda till date.

In Ayurveda, there exists a unique concept of rejuvenation measures to impart biological sustenance to bodily tissues. This is called as Rasayana which is claimed to strengthen the whole biological system as well as impart subtle divine characteristics to the individual. Some of these Rasayana are tissue and organ specific. Those drugs having a specific action on brain and cognitive properties are called Medhya Rasayana. Brahmi is one of such Medhya Rasayana which is very commonly used among all Ayurvedic practitioners. There exists a dispute in the Ayurvedic literature about the identity of exact species of Brahmi since many years. The reason for this is the Sanskrit verse in the Bhavaprakasha Nighantu which states that Brahmi is the synonym for both Jalabrahmi (Bacopa monnieri L. Penn) and Mandookaparni (Centella asiatica (L.) Urban).[4–6]

Taxonomically Bacopa monnieri and Centella asiatica are from totally different plant families (Scrophulariaceae and Apiaceae, respectively) and are very distinct in their morphology. Bacopa monnieri (BM) is a creeping, glabrous, somewhat succulent herb growing in wet places (photo plate 1). The plant is called Aindri and Bramhi in Sanskrit.[7,8] On the contrary, Centella asiatica (CA) is a slender, prostrate, glabrous herbaceous plant, rooting at the nodes. The leaves are simple, petiolate, palmately lobed[9] (photo plate 1). The Sanskrit name of the plant is Aindri, Mandookaparni, or Bramhi [Figure 1].[7,8]

Figure 1.

Brahmi and Mandookaparni

Though some of the texts have tried to rule out the controversy regarding identity of exact species of Brahmi, whether to use BM or CA, still some Ayurvedic practitioners and pharmacies accept the use of both these plants as Brahmi while making different formulations and are believed that both are equipotent in regard to their medicinal values. The present literature on evaluation of potential of these two plants on neurological and behavioral systems elucidates a remarkable efficacy of both these plants. Yet no studies till date have reported the comparative efficacy of BM and CA to resolve the dispute of identity of Brahmi. The Ayurvedic literature is based on the clinical experiences by the sages for many years and is accepted to be true clinically. However the same has not yet been validated using experimental studies which can even throw a light on the probable mechanism of action of these plants. Thus it becomes imperative to evaluate and compare in vitro free-radical quenching potential of BM and CA which could help identify exact species of plants to be used for Brahmi. Also it will help to validate the Ayurvedic concept of similar action potential of these two different species for the same vernacular name.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

All chemicals used for assays were of analytical grade. 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), TPTZ (2, 4, 6-tripyridyl-s-triazine), Quercetin and gallic acid were procured from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Acetic acid, sodium acetate, potassium persulfate (K2S2O8), sodium nitroprusside (SNP), ferric chloride (FeCl3·6H2O), hydrochloric acid (HCl), potassium hexacyanoferrate (K2Fe(CN)6), ferrous sulfate (FeSO4), and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) were purchased from Qualigens Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India.

Plant material

Bacopa monniri (BM) and Centella asiatica (CA) were collected from their natural habitat, identified, authenticated, and deposited at Medicinal Plant Conservation Centre (MPCC), Pune, India. Fresh leaves of BM and CA were collected early in the morning from mature plants with uniform growth, washed thoroughly under running water followed by distilled water, shed dried, and crushed in a common grinder.

Extraction

Ethanolic and aqueous extracts of BM and CA were prepared by mixing 10% powder in respective solvent by constant agitation on a shaker (120 rpm, ambient temperature, 24 hours).[10]

Biochemical evaluations

Total antioxidant activity (FRAP assay)

A slightly modified method of Benzie and Strain[11] was adopted for the FRAP assay. The stock solutions included 300 mM acetate buffer (3.1 g CH3COONa and 16 ml CH3OOH, pH 3.6), 10 mM TPTZ (2, 4, 6-tripyridyl-s-triazine) solution in 40 mM HCl, and 20 mM FeCl3·6H2O solution. This assay involved (i) preparation of fresh FRAP solution by mixing 25 ml acetate buffer, 2.5 ml TPTZ, and 2.5 ml FeCl3·6H2O, (ii) raising the temperature of the solution to 37°C, (iii) allowing plant extracts (150 μl) allowed to react with 2,850 μl of the FRAP solution for 30 minutes in the dark, and (iv) taking readings of the colored product (ferrous tripyridyl triazine complex) at 593 nm. The standard curve was linear between 200 and 1,000 μM FeSO4. Results are expressed in mM Fe (II)/g dry mass.

DPPH free-radical scavenging assay

Complementarities of the antioxidant capacity of the formulation was confirmed by the DPPH scavenging assay according to Brand-Williams et al.,[12] with slight modification. Different concentrations (100-1,000 μg/ml) of the extracts and ascorbic acid (standard) were thoroughly mixed with 5 ml of methanolic DPPH solution (33 mg/l) in test-tubes and the resulting solution was kept standing for 10 minutes at 37°C before the optical density (OD) was measured at 517 nm. The measurement was repeated with three sets and an average of the reading was considered. The percentage radical scavenging activity was calculated from the following formula:

% scavenging [DPPH] = [(A0–A1)/A0] × 100

where A0 is the absorbance of the control and A1 is the absorbance in the presence of the samples. IC50 values were calculated from the slope of the standard graph using the “y = mx + c” formula for every cases.

Reducing power assay

The Fe3+ -reducing power of the extract was determined by a method described by Hazra et al.,[13] with slight modification. The assay involved (i) mixing different concentrations (100-1,000 μg/ml) of the extracts in a phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 6.6) with potassium hexacyanoferrate (0.1%), (ii) incubation at 50°C for 20 minutes, (iii) arresting the reaction by addition of 10% tricarboxylic acid (TCA) and distilled water (2.5 ml), (iv) adding the FeCl3 solution (0.01%) to the upper portion of the reaction mixture, (v) leaving the reaction mixture for 10 minutes at room temperature for color development, and (vi) measuring absorbance at 700 nm. All tests were performed in triplicate. Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control. A higher absorbance of the reaction mixture indicated greater reducing power.

Nitric oxide scavenging assay

Nitric oxide, generated from sodium nitroprusside in aqueous solution at physiological pH, reacts with molecular oxygen to form nitrite ions. Sulfanilamide is quantitatively converted to a diazonium salt by reacting with nitrite under acidic conditions (5% phosphoric acid). This diazonium salt coupled with N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine (NED) forms an azo dye that can be measured quantitatively at 542 nm.[14]

Chemical reactions involved in the measurement of nitric oxide using the Griess reagent system: Briefly, the assay system involves (i) addition of buffer and sodium nitroprusside to various concentrations of extract, (ii) after incubation for 150 minutes at 25°C, addition of Griess reagent to initiate diazotization, (iii) addition of Griess B reagent to act as a chromophore, and (iv) finally, measuring the OD at 540 nm. The percentage radical scavenging activity was calculated from the following formula:

% scavenging [NO] = [(A0–A1)/A0] × 100

where A0 was the absorbance of the control and A1 was the absorbance in the presence of the samples.

Antilipid peroxidation assay

Decomposition of lipid membrane in the body leads to formation of malondialdehyde (MDA) along with other aldehydes and enals as the end-product. These react with thiobarbituric acid to form colored complexes. Hence these are called the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS). The complex of TBA-MDA is selectively detected at 532 nm using a double beam UV spectrophotometer.[15] Briefly, the assay involved (i) perfusion of goat brain with 0.15 M KCl, (ii) initiation of lipid peroxidation by addition of 1 mM FeCl3, (iii) stopping the reaction by adding ice-cold 0.25 N HCl containing TCA and TBA (this initiated the color development), (iv) addition of BHT, and (v) finally measuring the OD at 532 nm against solutions without FeCl3 (normal) and without drug (induced).

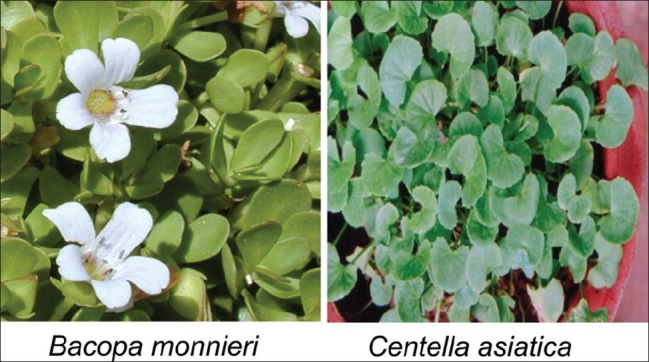

Determination of the total phenolic content

The amount of total phenolics present in extracts of BM and CA was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteau (FC) reagent as described by Hazra et al.[13] A gallic acid standard curve (R2 = 0.9) was used to measure the phenolic content [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Standard graph of gallic acid

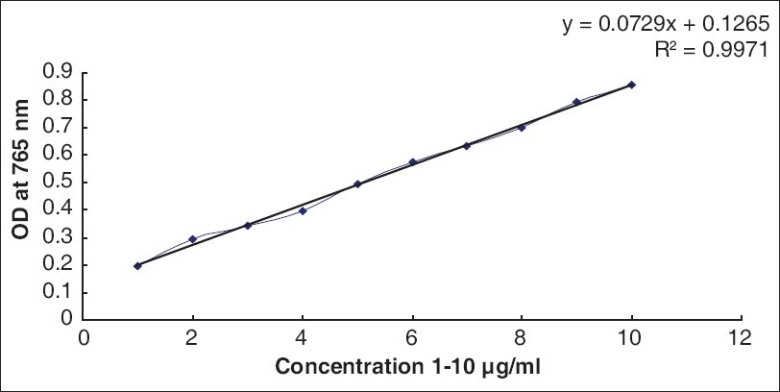

Determination of the total flavonoid content

The amount of total flavonoids present in extracts of BM and CA was determined using aluminum chloride reagent as described by Asgarirad et al.[16] A Quercetin standard curve (R2 = 0.9) was used to measure the total flavonoid content [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Standard graph of Quercetin

Results

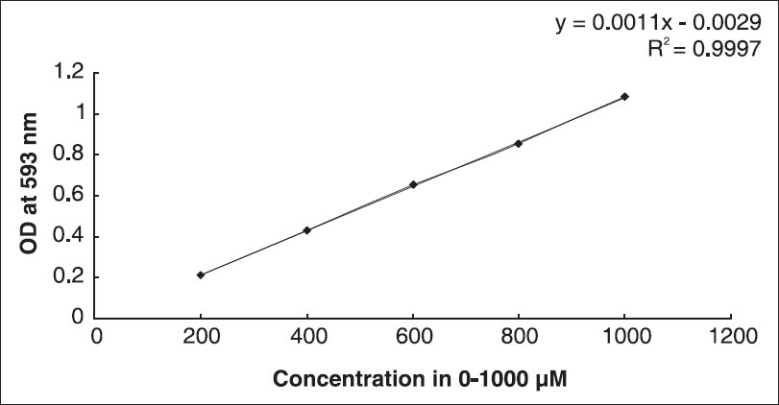

FRAP

The FRAP values are represented in terms of μM Fe (II)/g of dry mass of the sample. From the standard graph [Figure 4] of ferrous sulfate, the values for BM and CA were determined using the standard formula. Both aqueous and ethanolic extracts showed significant FRAP activity [Table 1].

Figure 4.

Standard graph of FeSO4

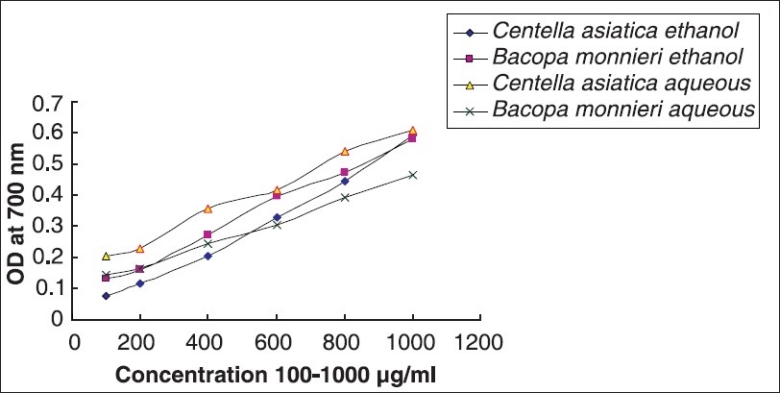

Table 1.

FRAP values (μM Fe (II)/g dry mass) of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of BM and CA

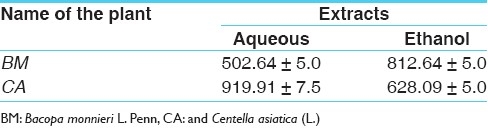

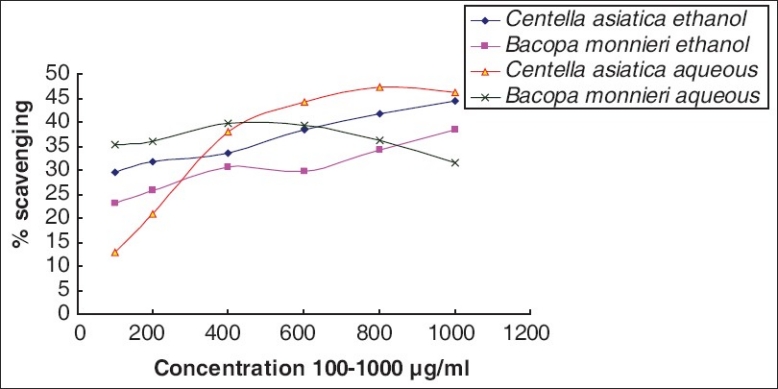

DPPH free-radical scavenging

Both BM and CA were found to be potent DPPH free-radical scavengers [Figure 5]. Comparatively higher activity (61-94% at conc. μg/ml) was observed in ethanolic extract of CA leaves while aqueous extracts showed lower activity. CA leaves showed higher free-radical scavenging activity compared to BM leaves in either solvent. IC50 values for the aqueous extracts of CA and BM were 94.66 and 76.42 μg/ml, while those of ethanolic extracts were 475 and 469 μg/ml for CA and BM, respectively.

Figure 5.

Comparative DPPH free-radical scavenging activity of Bacopa monnieri L. Penn and Centella asiatica (L.)

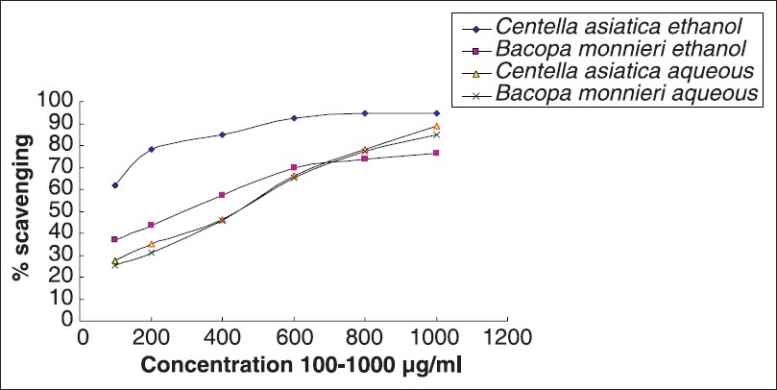

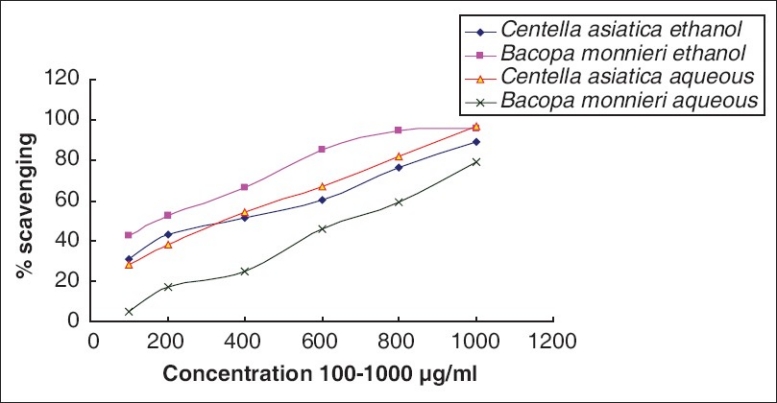

Reducing potential assay

Although both aqueous and ethanolic extracts of the two plants have shown significant reducing potential, aqueous extract of leaves of CA showed maximum activity (OD 0.608 at conc. 1,000 μg/ml, at 700 nm). However, there was no significant variation in the activity for all the extracts [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Comparative reducing potential by Bacopa monnieri L. Penn and Centella asiatica (L.)

NO scavenging

For scavenging NO free radical in vitro, aqueous extract of CA exhibited maximum efficacy (46.27% at conc. 1,000 μg/ml) [Figure 7] and the activity was reduced in aqueous extract of BM.

Figure 7.

Comparative NO scavenging by Bacopa monnieri L. Penn and Centella asiatica (L.)

Antilipid peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation is one of the major events that occur during oxidative damage. Both aqueous as well as ethanolic extracts of CA and BM have antilipid peroxidation activity which is maximum at 1,000 μg/ml of the extracts. In the case of aqueous extracts, CA showed more protective potential for lipid peroxidation activity (97.37% at conc. 1,000 μg/ml) while BM had significantly less efficacy (79.02% at conc. 1,000 μg/ml). On the contrary, ethanolic extract of BM had more activity (95.78%) than that of CA (89.16%) at concentration 1,000 μg/ml [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

Comparative ALP potential of Bacopa monnieri L. Penn and Centella asiatica (L.)

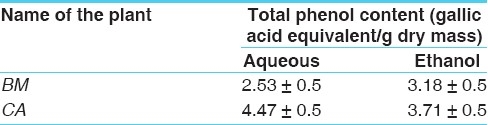

Total phenol content

Phenols play a vital role in the free-radical scavenging properties of plants.[17,18] The total phenolic content in ethanolic extracts of BM and CA was found to be 3.18 and 2.53 μg/ml of Gallic acid equivalent respectively, while that of aqueous extracts were 3.71 and 4.47 μg/ml of Gallic acid equivalent, respectively [Table 2].

Table 2.

Total phenol content (gallic acid equivalent/g dry mass) of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of BM and CA

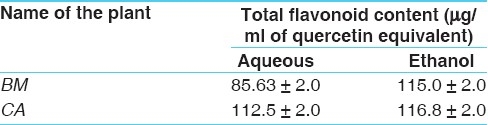

Total flavonoid content

The total flavonoid content was found to be higher in aqueous extracts of CA than BM (112.5 and 85.63 μg/ml of Quercetin equivalent, respectively) and comparable (116.8 and 115.0 μg/ml of Quercetin equivalent respectively) in ethanolic extracts. This shows that the two plants are significantly rich in flavonoid content [Table 3].

Table 3.

Total flavonoid content (μg/ml of quercetin equivalent) of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of BM and CA

Discussion

BM is a well-known memory enhancer mentioned in the Ayurvedic system of medicine[19] where special mention is made about this plant in treatment of asthma, insanity, and epilepsy.[20] The major chemical entity shown to be responsible for the said neuropharmacological effect, nootropic action, and antiamnestic effects is saponin Bacoside A, along with Bacoside A3, Bacopaside II, Jujubogenin isomer of Bacopasaponin C, and Bacopasaponin C.[19,21] The antioxidant properties and its ability to counter-balance the enzymes such as (i) SOD (superoxide dismutase) and (ii) catalase levels in the cells are also attributed to the same saponin (Bacoside A).[19] The aqueous extract of this plant is known to have a tranquilizing effect on experimental rats and dogs.[19]

CA leaves and entire plants are used therapeutically in the traditional Ayurvedic system to restore youth, memory, and longevity.[22] Cognitive enhancing effects of aqueous extract of CA have been shown to be associated with an antioxidant mechanism in the CNS in rats following oral administration.[23] Ayurvedic poly-herbal formulations, including CA, are used to retard age and prevent dementia, and the herb combined with milk is given to improve memory,[24] whereas CA has been used for combating physical and mental exhaustion[25,26] in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM).

DPPH free-radical scavenging and reducing power

Plants with antioxidant activities have been reported to possess free-radical scavenging potentials.[27] In our studies, we have found that both BM and CA are potent DPPH free-radical scavengers. Aqueous as well as ethanolic extracts of both the plants have shown significant DPPH radical scavenging efficacy. However, there are no significant differences in the IC50 value for both aqueous (94.66 and 76.42 μg/ml of CA and BM, respectively) as well as ethanolic extracts of CA and BM (475 and 469 μg/ml for, respectively). This suggests that these plants in their aqueous and ethanolic extract contain compounds that are capable of donating hydrogen to a free radical in order to remove odd electron which is responsible for radical's reactivity.[27]

Free iron is a potential enhancer of reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation as it leads to reduction of H2O2 and generation of the highly aggressive hydroxyl radical.[28] In the reducing power assay, the presence of antioxidants in the sample would result in the reduction of Fe3+ to Fe2+ by donating an electron. The amount of Fe2+ complex can then be monitored by measuring the formation of Perl's blue at 700 nm. Increasing absorbance indicates an increase in reductive ability.[27] Also, reducing power of a compound serves as a significant indicator of its antioxidant activity.[29] When aqueous and ethanolic extracts of BM and CA were assayed for the reducing power activity CA showed maximum activity (OD 0.608 at conc. 1,000 μg/ml, at 700 nm), and no significant variation was observed in the reducing potential in either of the solvents used [Figure 6].

Importance of NO-scavenging efficacy as a cognition enhancer

Both aqueous and ethanolic extracts of CA and BM showed moderate in vitro nitric oxide-scavenging activity. CA aqueous extract showed highest activity of 46% at a concentration 1,000 μg/ml [Figure 7]. It is known that along with ROS, reactive nitrogen species (RNS) plays a pivotal role in several ailments like inflammation, cancer, and other pathological conditions.[30] NO is known to be a ubiquitous free-radical moiety, which is distributed in tissues or organ systems and is supposed to have a vital role in neuromodulation or as a neurotransmitter in the CNS.[31] Further, nitric oxide free radical (NO) can react with superoxide radical to form highly toxic peroxynitrite anion (ONOO-), which upon reacting with tissue or body fluid generates nitrotyrosines. These nitrotyrosines are detected in human brain and may be increased in neurodegenerative diseases, especially because glial cells and macrophages generate nitric oxide.[28] Thus in vitro NO-quenching potential of both aqueous and ethanolic extracts of BM and CA may provide a possible mechanistic clue to the traditional knowledge that these two plants act as a nootropic agent or enhance cognition.

Interrelation between DPPH radical and anti lipid peroxidation assay

Lipid peroxidation is a major harmful consequence of ROS formation, as it reflects irreversible oxidative changes of membranes.[32] It is known that any free radical remains with sufficient energy to abstract a hydrogen atom from a methylene carbon of an unsaturated long chain fatty acid and can initiate a lipid peroxidation reaction, which increases in many oxidative damage-induced diseases. Reasons for this increased peroxidizability of damaged tissues include (i) inactivation of some antioxidants and/or (ii) leakage of antioxidants from the cell. Naturally occurring as well as cellular antioxidants protect these processes at different levels within cells by (a) preventing radical formation; (b) intercepting radicals when formed; (c) repairing oxidative damage caused by radicals; (d) increasing the elimination of damaged molecules.[33] In the anti-lipid-peroxidation assay, aqueous extracts of CA showed comparatively higher lipid peroxidation protection activity (97.37% at conc. 1,000 μg/ml) than that of BM (79.02% at conc. 1,000 μg/ml). On the contrary, the efficacy was comparable in ethanolic extract (89.16% for CA and 95.78% for BM at conc. 1,000 μg/ml). This activity of the extracts may be attributed to their hydrogen-donating ability.

It is also known that free radical causes harmful autooxidation of unsaturated lipids in food[34] and natural antioxidants and either (i) intercept the free-radical chain of oxidation or (ii) donate hydrogen from the phenolic hydroxyl groups; thereby forming a stable end product, which does not initiate or propagate further oxidation of lipid.[34] It is known that brain is rich in PUFAs, and is vulnerable to ROS-induced oxidative damage.[35,36] Both BM and CA are found to be potent free-radical scavenger, in vitro. Thus the antilipid peroxidation activity of these two plants may be due to their strong free-radical quenching potentials and also can be a possible clue for their neuro-protective potential as described by the Ayurvedic system.

Correlation between flavonoid, phenol content and antioxidant

Antioxidant activities are known to increase proportionally to the polyphenol content. This activity is believed to be mainly due to their redox properties,[17,18] which plays an important role in (a) adsorbing and neutralizing free radicals, (b) quenching singlet and triplet oxygen, and (c) decomposing peroxides.[37] Also according to recent reports, a highly positive relationship between total phenols and antioxidant activity appears to be the trend in many plant species. Naturally occurring antioxidants such as phenols, flavonoids are well known to have very less or no side effects and hence are considered to be safe.[16] In our study, we found that the total phenolic content in aqueous extract of CA was higher than that of BM; while phenol content in ethanolic extracts was comparable [Table 2]. This may be one of the causes for their strong free-radical scavenging potential. Similarly, total flavonoid content in the ethanolic extracts of the studied plants were comparable, while CA showed significantly higher flavonoid content in aqueous extract than that of BM [Table 3]. In plants, polyphenol compounds like flavonoids, which contain hydroxyl functional groups, are supposed to be responsible for the radical scavenging effect.[16,38,39] Flavonoids also play vital role as antitumoural, antiischemic, antiallergic, antiulcerative, and anti-inflammatory. They are known to inhibit several enzyme activities such as lipoxygenase, cyclooxygenase, monooxygenase, xanthine oxidase, glutathione-S-transferase, mitochondrial succino-oxidase, and NADH oxidase.

Many of the biological activities of flavonoids are attributed to their antioxidant properties and free-radical scavenging capabilities.[28] According to our study, the contents of these bioactive phytochemical compounds in BM and CA extracts can explain their antioxidant activity. Also, there exists a strong relation between total phenol and flavonoid content and polarity of the extraction solvent.[16] As our results suggest that aqueous extracts give a significant difference in the phenol as well as flavonoid content in these two plants, while there is a marginal difference in the ethanolic extracts.

All the above results highlight the potent free-radical quenching potentials of CA and BM and support their traditional uses in various ailments as well as Medhya Rasayana. The probable mechanism of action of these two plants on cognition and memory would be through prevention of neuronal damage which is due to increased oxidative stress.

Conclusion

Brahmi is the one of the most studied Ayurvedic plant for its cognition enhancing activity. Our results suggest that both Bacopa monnieri and Centella asiatica are equipotent with regard to their free-radical quenching potentials and hence can be alternatively used. This also supports the Ayurvedic belief of the plants having similar activity as mentioned in ancient texts and opens a new arena of evaluation of these plants to elucidate their exact mechanism of action.

Acknowledgment

The authors are thankful to BVU for supporting this work, Prof. S. P. Mahadik for his constant support and valuable discussions during the progress of this work and Prof. P K Ranjekar for critically going through the manuscript. We also extend our sincere thanks to Prof. Jhunjarrao, Principal, and Dr. Sangeeta Bhagat, Professor, Department of Biotechnology, Modern College of Arts, Science and Commerce, Shivajinagar, Pune for their support and encouragement.

References

- 1.Dewick PM. John Wiley and Sons. 1997. Drugs from nature Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joy PP, Thomas J, Mathew S, Skaria BP. Medicinal plants. Kerala, India: Kerala Agricultural University, Aromatic and Medicinal Plants Research Station; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patwardhan B, Vaidya AD, Chorghade M. Ayurveda and natural products drug discovery. Curr Sci. 2004;86:789–99. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sri Bhavamishra, Nighantu Bhavaprakash, varga Guduchyadi. In: nth ed. Pandey GS, editor. Varanasi, India: Chaukhamba Bharati Academy; 2002. 283. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aacharya Vaidya Jadavaji Trikamji., editor. Agnivesa, Charaka, Caraka Samhita. 5th ed. Varanasi, India: Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhavamishra Sri, Nighantu Bhavaprakash, Dwivedi VN., editors. Banaras, India: (Hindi translation), Motilal Banarasi Das Publication; 1949. p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kareem AM. Plants in Ayurveda (A compendium of Botanical and Sanskrit names) Bangalore, India: Foundation for Revitalisation of Local Health Tradition; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma PV. Dravyaguna-vijnana. Vol. 2. India: (In Hindi), Chaukhambha Bharati Academy; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirtikar KR, Basu BD. Indian médicinal plants. Delhi, India: M/S Periodical Experts Ed; 1935. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parekh J, Chanda SV. In vitro antimicrobial activity and phytochemical analysis of some Indian medicinal plants. Turk J Biol. 2007;31:53–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benzie IF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal Biochem. 1996;239:70–6. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier M, Berset C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. Lebenson Wiss Technol. 1995;28:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hazra B, Biswas S, Mandal N. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activity of Spondias pinnata. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:63–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sreejayan N, Rao MN. Nitric oxide scavenging by curcuminoids. J Pharma Pharmacol. 1997;49:105–9. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1997.tb06761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wade J, Van R. Quantitation of malonaldehyde (MDA) in plasma, by ion-pairing reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography. Biochem Med. 1985;33:291–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-2944(85)90003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asgarirad H, Pourmorad F, Hosseinimehr SJ, Saeidnia S, Ebrahimzadeh MA, Lotfi F. In vitro antioxidant analysis of Achillea tenuifolia. Afr J Biotechnol. 2010;9:3536–41. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adedapo AA, Jimoh FO, Afolayan AJ, Masika PJ. Antioxidant activities and phenolic contents of the methanol extracts of the stems of Acokanthera oppositifolia and Adenia gummifera. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:54–60. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng W, Wang SY. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in selected herbs. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:5165–70. doi: 10.1021/jf010697n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gohil KJ, Patel JA. A review on Bacopa monniera: Current research and future prospects. Int J Green Pharm. 2010:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chopra RN. Indigenous drugs of India. 2nd ed. Calcutta (India): U N Dhur and Sons; 1958. pp. 341–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deepak M, Sangli GK, Arun PC, Amit A. Quantitative determination of the major saponin mixture bacoside A in Bacopa monnieri by HPLC. Phytochem Anal. 2005;16:24–9. doi: 10.1002/pca.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapoor LD. CRC Handbook of Ayurvedic medicinal plants. Florida (NY): CRC Press LLC; 2005. pp. 208–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar VM, Gupta YK. Effect of different extracts of Centella asiatica on cognition and markers of oxidative stress in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;79:253–60. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00394-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manyam BV. Dementia in Ayurveda. J Altern Complement Med. 1999;5:81–8. doi: 10.1089/acm.1999.5.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brinkhaus B, Lindner M, Schuppan D, Hahn EG. Chemical, pharmacological and clinical profile of the East Asian medical plant Centella asiatica. Phytomedicine. 2000;7:427–48. doi: 10.1016/s0944-7113(00)80065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duke JA, Ayensu EA. Medicinal plants of China. Algonac, Michigan (NY): Reference Publications; 1985. p. 705. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olayinka AA, Anthony IO. Preliminary phytochemical screening and in vitro antioxidant activities of the aqueous extract of Helichrysum longifolium DC. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010;10:21–5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh RP, Sharad S, Kapur S. Free radicals and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases: Relevance of dietary antioxidants. J Indian Acad Clin Med. 2004;5:218–25. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhaumik UK, Kumar AD, Selvan VT, Saha P, Gupta M, Mazumder UK. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging property of methanol extract of Blumea lanceolaria leaf in different in vitro models. Pharmacologyonline. 2008;2:74–89. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nabavi SM, Ebrahimzadeh MA, Nabavi SF, Hamidinia A, Bekhradnia AR. Determination of antioxidant activity, phenol and flavonoids content of Parrotia persica Mey. Pharmacologyonline. 2008;2:560–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gulati K, Ray A, Masood A, Vijayan VK. Involvement of nitric oxide (NO) in the regulation of stress susceptibility and adaptation in rats. Indian J Exp Biol. 2006;44:809–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milei J, Pedro F, César GF, Daniel RG, Gabriele I, Massimo C, et al. Relationship between oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, and ultrastructural damage in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing cardioplegic arrest/reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:710–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gutteridge JM. Lipid Peroxidation and antioxidants as biomarkers of tissue damage. Clin Chem. 1995;41:1819–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chourasiya RK, Jain PK, Jain SK, Nayak SS, Agrawal RK. in-vitro antioxidant activity of Clerodendron inerme (l.) Gaertn leaves. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci. 2010;1:119–23. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kulkarni OP, Mukherjee S, Pawar NM, Awad VB, Jagtap SN, Kalbhor VM, et al. Ambiguity in the authenticity of traded herbal drugs In india: Biochemical evaluation with a special Reference to Nardostachys jatamansi DC. J Herb Med Toxicol. 2010;4:229–35. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schroeter H, Williams RJ, Martin R, Iversen L, Rice-Evans CA. Phenolic antioxidants attenuate neuronal cell death following uptake of oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:1222–33. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang M, Li J, Rangarajan M, Shao Y, La Voie EJ, Huang T, et al. Antioxidative phenolic compounds from Sage (Salvia officinalis) J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:4869–73. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Das NP, Pereira TA. Effects of flavonoids on thermal autooxidation of Palm oil: Structure-activity relationship. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1990;67:255–8. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Younes M. Inhibitory action of some flavonoids on enhanced spontaneous lipid peroxidation following glutathione depletion. Planta Med. 1981;43:240–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]