Abstract

Context:

Dental remains are usually the last to get destroyed among body parts after death. They may be useful for personal identification in cases of mass disasters and decomposed unidentified bodies. Dental records may help in the identification of suspects in criminal investigations and in medicolegal cases. Maintenance of dental records is legally mandatory in most of the European and American countries. Unfortunately, the law is not very clear in India, and the awareness is very poor.

Aims:

To assess the awareness regarding the dental record maintenance among dentists in Rajasthan, to deduce the quality of average dental records kept by them and to evaluate the potential use of their maintained records, in any of forensic or medicolegal cases.

Settings and Design:

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 100 dental practitioners of different cities in Rajasthan, India.

Materials and Methods:

Data were collected through a structured questionnaire, which was responded by the study population in the course of a telephonic interview. The questionnaire addressed on the mode of maintaining dental records in their regular practice.

Statistical Analysis Used:

The data so gathered were subjected for descriptive analysis.

Results:

As for knowledge or awareness about maintaining dental records, surprisingly a very low percentile (about 38%) of surveyed dentists maintained records. Sixty-two percent of the dentists were maintaining no records at all.

Conclusion:

Nonmaintenance or poor quality of records maintained indicates that the dentists in Rajasthan are not prepared for any kind of forensic and medicolegal need if it arises.

Keywords: Child abuse, dental remains, dentists, forensic odontology, medicolegal cases, personal identification

Introduction

Dental records are an essential component serving as an information source for dentists and the patients, in medicolegal, administrative financial function within general practice for quality assurance and audit. It is said that dentists and patients forget but good records remember. Every practicing dentist has a legal duty, as in keeping some sort of record of each patient for whom they are providing the dental care.[1]

The ability of clinical practitioners to produce and maintain accurate dental records, which is the detailed document of the history of the illness, physical examination, diagnosis, treatment, and management of a patient and is essential for good quality patient care as well as it being a legal obligation. The primary purpose of maintaining dental records is to deliver quality patient care and follow-up. With the increasing awareness among the general public of legal issues surrounding health care, in forensic purposes, and with the worrying rise in malpractice of insurance claim cases, a thorough knowledge of dental record issues is essential for any practitioner.[2]

Dental records can also be used for and have an important role in teaching and also in research. Dental professionals are compelled by law to produce and maintain adequate patient records. Good record-keeping is fundamental to good clinical practice and is an essential skill for practitioners. The code of practice on dental records documents the minimum requirements for recording and maintaining dental records and describes some of the underlying principles to be applied by the practitioners in their record-keeping.[1]

Record maintenance is legally mandatory in the American and European countries,[3] but the rules are not clear in India and there is ignorance regarding the same among the dentists in our country with most of the dentists maintaining a poor quality or no dental record at all. Hence we conducted this study to assess the awareness regarding the dental record maintenance and to determine the quality of average dental records kept by the dentists in Rajasthan, India. The other objective was also to evaluate the potential use of their maintained records, in any of the forensic or medicolegal cases.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among hundred practicing dentists who were selected randomly from different cities of Rajasthan State, India. Their contact numbers were obtained online. All the practicing dentists were called over telephone, the nature and purpose of the survey was explained, and consent was obtained. During the call they were also inquired on the convenient time for contacting them to collect the responses.

A 48-item structured questionnaire was used to assess the mode of dental records maintenance among dental practitioners, prepared as per ADA guidelines,[3] Garcia,[4] and Dierickx et al.[5] The assessment of content validity in the questionnaire was related to the opinions expressed by a group of 5 academicians working in the institution in addition to possessing their own dental clinic set up. The mean content validity ratio (CVR) was calculated as 0.89. Content validity identifies whether the measure represents all the facets of a given construct. The questionnaire was further pre-tested to assess its feasibility and reliability, which were found to be satisfactory. Test of reliability comprised two components: question–question reliability, which was assessed by the percentage of agreement (90%) and internal reliability for the responses to questions, which was assessed using Cronbach's alpha (0.84). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board.

On the day of appointment the investigator made a call and obtained the responses in Yes/No format. There was no need for any test of significance here as this was a descriptive study.

Results

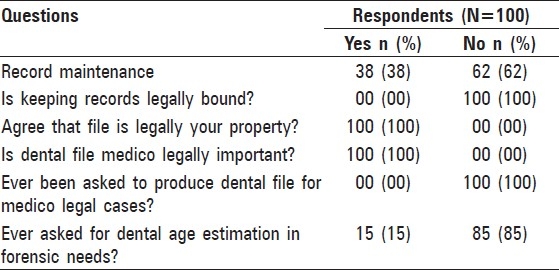

As for knowledge or awareness about maintaining dental records, surprisingly a very low percentile of about 38% of surveyed dentists maintained records. Sixty-two percent of the dentists were maintaining no records at all [Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of knowledge about record maintenance and its importance among dental practitioners

When asked about whether in India is it mandatory to legally maintain the records, 100% response was no. But when enquired about the legal rights of owning the records and whether it was medicolegally important, all 100 agreed to be yes. As for potentiality of these records for forensic needs were evaluated, none were asked to produce any records in forensic court of law and only 5% were asked for age estimation of teeth in other forensic cases [Table 1].

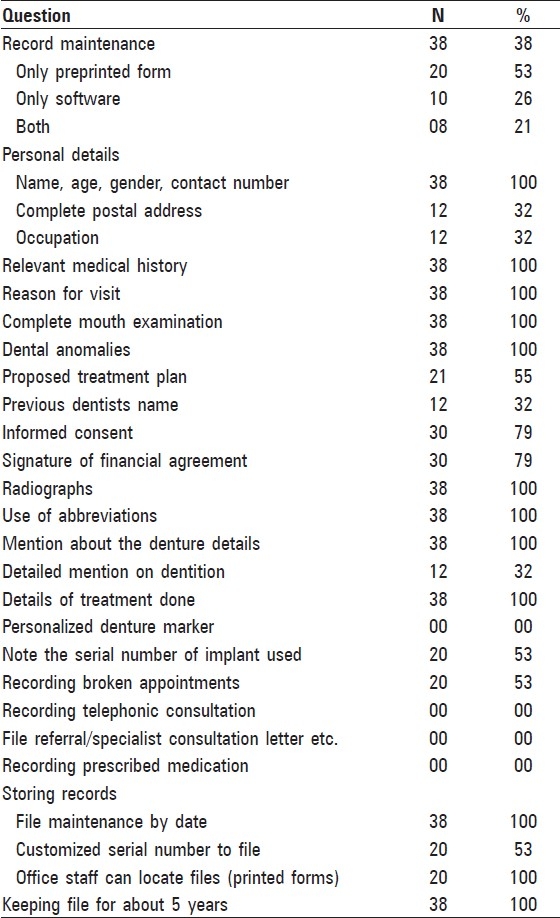

There was 100% maintenance of few records, such as name, age, gender, contact number, relevant medical history, reason for visit, complete mouth examination, dental anomalies and details of denture delivered, treatment done, and also maintained these records for at least 5 years. Informed consent and signature of financial agreement were obtained in 79% of dental records. Only about 53% of them recorded the broken appointments, noted the serial number of the implants used and gave a customized serial number to the file. Although all 38 dentists took the radiograph, marked the details on the radiograph, and also maintained it in the file, none wrote the details of the radiographs in the files or took signatures when the radiographs or casts were given to patients for their need. Most vital data, such as complete postal address, occupation, previous dentist name and dentition details were found in about 32% of dental records. None of them recorded, the drug that was prescribed, the telephonic conversation or preserved the referral letters and personalized denture marker [Table 2].

Table 2.

Percentage distribution of various components in maintained records

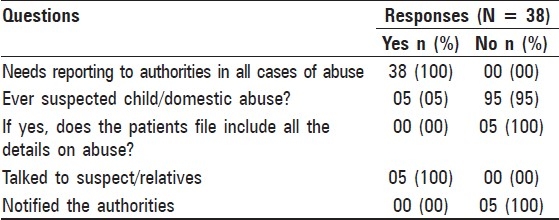

Regarding suspicion of child or domestic abuse in patients, only 5% suspected of domestic abuse and spoke to the relatives regarding the same, but none notified the concerned authorities. But all agreed that it would be intimated in severe cases [Table 3].

Table 3.

Responses among dental practitioners who maintained dental records on cases of abuse

Discussion

There is the need for maintaining the records officially and professionally to protect against any commercial, legal, and medicolegal litigation. Records are the most important factors needed to prevail in the lawsuit. Written records, including medical and dental history, chart notes, radiographs, photographs, and models, are the only available guidelines from which to deliberate in a negligent lawsuit and must be meticulously kept. All records must be contemporaneous, and must be signed and dated. Legally, dentist written records carry more weight than patient's recollections.[6]

The present study with regard to awareness, showed that none of the dentists surveyed were aware that it is legally mandatory to maintain records. Everyone answered that it is not mandatory in India. This shows that dentists are often ignorant about the laws governing their profession. However, the Indian law says altogether a different story. Under Article 51 A(h) of the Constitution of India, there is a moral obligation on the doctor, and a legal duty, to maintain and preserve medical, medicolegal, and legal documents in the best interests of social and professional justice.[7]

It is necessary to maintain accounts to avoid action from Income Tax authorities under Section 44 AA of the Income Tax Act, 1961. Official records and documentation should be preserved for observation for a minimum of 8 years to avoid attracting penalties under Section 271[1] of Income Tax Act, 1961.[7]

For legal suits, maintenance of judicial records is required for minimum 2 years in consumer cases (The Consumer Act of India, 1986), 3 years in civil cases with no time limit in criminal cases.[7]

Dental negligence falls under section 2 (0) of the Consumer Protection Act (CPA) because Indian Dentist Act had no provision to

entertain any complaint from the patient

take action against dentist in case of negligence

award compensation.

The CPA was passed by the Indian Parliament in the year 1986 to safeguard and to protect the interest of consumers. Prior to the enforcement of this Act, cases against dentists were decided by civil courts and even under Indian Contract Act. But the disadvantage of the latter was high cost and more time consuming.

Advantages of Consumer Protection Act

Court fee is less.

Speedy justice.

Procedural simplicity. Complainants can state their own case without a lawyer.

A non-intimidating atmosphere and encouragement to settle case without too much of formalities and lengthy procedures.[6]

Under Section 17-A of the Dentists Act, 1948, there are several benefits for those who are good at record maintenance in order to maintain professional respect and dignity for doctors. The Indian Dental Association (IDA) recommends that for practicability, a doctor may maintain records up to a minimum of 5 years to satisfy consumers and the judiciary, for protection against medical negligence and complications. These records in question relate to the consent form, detection, diagnosis, and follow-up treatment records and recorded allergies for protection of life of a patient. But the Dental Council of India has not prescribed anything specific and there is no regulation in force for a professional administration.[7]

The legal avenues (other than CPA) available to aggrieved patients to sue against health professionals.[8]

Medical Council of India and Dental Council of India.

Civil Courts.

Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Commission (MRTP)

Public Interest Litigation.

Sections of Indian Penal Code, 1860.

In the present study, as per quality of record maintenance a very low percentile (38%) of surveyed dentists maintained records. Most vital data, such as complete postal address, occupation, previous dentist name, and dentition details, were found in about 32% of dental records. Informed consent was not obtained in 21% of dentist's records. However, the story is not much different in other countries.

Using ADA's published recommendations for structure and guidelines of the dental record from 1987, a 20-item questionnaire was developed, pre-tested, and used to survey a random sample of 750 Minnesota dentists. Data analysis revealed that information was absent in 9.4%–87.1% of the time. While 15% of respondents used a single-page record format, 44% used multiple forms filed in a specific location within the record. Of the dentists responding, 85% felt their record documentation was adequate without comparison to any specified criteria. Hence it was concluded that inadequate dental record components should be targeted for improvement.[9]

Helminen et al. assessed the quality of oral health record-keeping in public oral health care in relation to dentists’ characteristics among those who were born in 1966–1971 and clinically examined during 1994. Criteria for assessment of oral health record entries were based on Finnish health legislation and detailed instructions of health authorities. The results showed that each patient's identity was available in 90% of documents. Recordings concerning continuity of comprehensive care were infrequent; a questionnaire concerning each patient's up-to-date health history was in only 26% of the oral health records. Notes concerning each patient's bite and function of the temporomandibular joint were in 37% of the records, notes about oral soft tissues were in 11%, and the check-up interval was recorded in 21%. Recording of indices on periodontal and dental status varied greatly; the community periodontal index of treatment need was found in 93% and the index of incipient lesions in 16% of the records. Female dentists and dentists younger than 37 years tended to record more information. Conclusion of this study emphasized that dentists should be encouraged to better utilize the options offered by oral health records for individual treatment schemes.[10]

Informed consent was practically nonexistent till the time CPA came into existence. This is seen as more of a legal requirement than an ethical moral obligation on the part of the doctor towards his patient. An important aspect of several Medical Consumer litigations is improper consent and withholding complete information from the patient. This has been the subject matter of judicial scrutiny in various cases under CPA, as it pertains to patient's right of freedom while undergoing treatment. Hence it is of paramount importance for a doctor to have a proper legally valid consent from his patients.

The Indian scenario is somewhat different from the West with respect to the doctor–patient relationship. Here, the doctor–patient relationship is governed more by trust wherein doctor is the authoritative figure. Illiterate population which is less aware about the consumer rights and an already overburdened health services are few of the factors responsible for loss of basic essence of informed consent.

In current medical practice most therapeutic as well as diagnostic procedures involve risks. It is the duty of the physician to promote and protect the health and basic fundamental rights of the patient. Except emergency cases, in elective care where there is time for consultation, clinicians should discuss the case in detail with the patient or with his nominated representatives. In India the real enemy of informed consent is insufficient resources and inadequate manpower to allow enough available time for the detailed communication to occur. However, it should be remembered that an informed consent is a patient's right and a physician's duty.[11]

Although in the present study there was no requirement of the dental records in any forensic or legal cases, as it is a study with small sample size and may not reflect the existing picture. There are few studies which have shown the need of these records for the same. Practicing dentists can become valuable members of the dental identification process by developing and maintaining standards of record-keeping, which would be valuable in restoring their patients’ identity. A study was conducted on two groups of dentists who were asked to self-assess the forensic value of the dental records maintained in their own practices. The three most frequently recorded identifying dental features other than caries and restorations, were the presence of diastemas, displaced or rotated teeth, and dental anomalies. Surveyed dentists imbedded identifying information into the removable prosthetic devices fabricated for their patients an average of only 64% of the time. Only 56% of the two groups combined felt that their dental chartings and written records would be extremely useful in dental identifications. It was concluded that the quality of antemortem dental records available for comparison to postmortem remains varied from inadequate to extremely useful.[12]

In another study all forensic odontology cases referred to the department of forensic medicine in Göteborg between 1983 and 1992 were studied with regard to the instructions for dental records from the National Board of Health and Welfare. Results of the analysis showed that information on dental characteristics, normal anatomical findings and restorative treatment was complete in 43 (68%) of the cases, incomplete in 17 (27%) and missing in 3 (5%). Registration of previous therapy were missing in about 75 (94%) of the records. It was possible to identify patient radiographs in only 16 of the 40 records where radiographs were available. In spite of this, the inaccuracies in the records did not seem to hamper the identification procedures in this study which could be explained by the character of the cases and the availability of medical and circumstantial information.[13]

When asked about suspicion of child and domestic abuse in their patients, only 5% suspected domestic abuse in female patients, but sadly did not inform any concerned authorities. Also agreed that they would definitely inform higher authorities in severe cases which they have not come across till now.

The diagnosis of child sexual abuse often can be made based on a child's history. Physical examination alone is infrequently diagnostic without the history and/or some specific laboratory findings. The duty of the doctor is to interpret trauma, collect specimens, treat injury and above all, help and support the vulnerable patient. It is not part of a medical practitioner's remit to assess guilt, comment on anyone's truthfulness or state whether or not a crime has been committed; all of these are in the province of the court. Injuries often speak for themselves and are usually more eloquent for being allowed to do so. Close adherence to protocols and procedures that preserve the integrity of medical records, meticulous documentation and all clinical and forensic science evidence gathered can only enhance the value of medical evaluation of sexual violence. Attention to detail will benefit the patient by improving the identification of trauma and ensuring more effective investigation and prosecution of the assailant.[14]

However the results of our study suggest that the dentists in Rajasthan, India, either don’t have records or have the ones which are inadequate. This sends an alarm for increase in awareness for maintaining a good quality records, which indicates that these dentists are not at all prepared for any kind of forensic and medico legal needs, be it for cases of consumer forum, civil or criminal litigation or for personal recognition in mass disaster and any personal identification in criminal or homicide investigation cases. This study indicates big loopholes in our profession. The overall quality of record-keeping was poor, and in line with the findings of other worldwide studies.[9,10,12,13,15] In recognition of the inadequacies of many existing dental record systems, which do not lead the dentist through a logical sequence of recording, a new form of record card should be made available to prompt the practitioners for what should be routinely recorded. A proper guideline document on examination and record-keeping in dental practice should be prepared.[16] To achieve the positive changes in maintaining the standard of keeping record, proper education is to be given among undergraduates[17] and postgraduates and also raise awareness in practicing dentists.[18] It is the extraction, cataloging and interpretation of dental data, which form the large part of the science of forensic odontology. To conclude a dentist's responsibilities are production, retention, and release of clear and accurate patient records.[19]

Our study had quite a small sample size, akin to a pilot study, which may not reflect the authentic picture of the whole country. Hence further studies nationwide with larger sample size, standardized questionnaire, and inclusion of more criteria's are required to determine the standard that exists, which can bring out the real picture and point out the needs to be fulfilled.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ramesh N. HOD, Department of Community Dentistry for helping us in structuring the manuscript, all the Private Practitioners who sincerely participated in the study and also the staff of Pacific Dental College and Hospital for their support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Charangowda BK. Dental records: An overview. J Forensic Dent Sci. 2010;2:5–10. doi: 10.4103/0974-2948.71050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawney M. For the Record. Understanding Patient Record keeping. N Y State Dent J. 1998;64:34–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Clinical guideline on record-keeping. Pediatr Dent. 2004;26(7 Suppl):134–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin Garcia P, Rios Santos JV, Sequra Eqea JJ, Fernandez Palacin A, Bullon Fernandez P. Dental audit (I): Exact criteria of dental records; Results of a Phase - III study. Med Oral Pathol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E407–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dierickx A, Seyler M, de Valck E, Wijffels J, Willems G. Dental records: A Belgium study. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 2006;24:22–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhawan R, Dhawan S. Legal aspects in dentistry. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2010;14:81–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maintenance of Records. [Last accessed on 2010 Oct 18th]. Available from: http://www.ida.org.in/DentalPracticeAccreditation/maintenanceofrecords.htm .

- 8. [Last cited on 2010 Oct. 18th]. Consumer Protection Act and Medical Profession - The Legal Avenues Other Than CPA available from: http://www.medindia.net/indian_health_act/consumer_protection_act_and_medical_profession_the_legal_avenues_other_than_cpa.htm#ixzz1bD6fGULC .

- 9.Osborn JB, Stoltenberg JL, Newell KJ, Osborn SC. Adequacy of dental records in clinical practice: A survey of dentists. J Dent Hyg. 2000;74:297–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helminen SE, Vehkalahti M, Murtomaa H, Kekki P, Ketomäki TM. Quality evaluation of oral health record-keeping for Finnish young adults. Acta Odontol Scand. 1998;56:288–92. doi: 10.1080/000163598428464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bansal YS, Singh D. Medico-legal aspects of informed consent. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol. 2007;1:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delattre VF, Stimson PG. Self-assessment of the forensic value of dental records. J Forensic Sci. 1999;44:906–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borrman H, Dahlbom U, Loyola E, René N. Quality evaluation of 10 years patient records in forensic odontology. Int J Legal Med. 1995;108:100–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01369914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakelliadis EI, Spiliopoulou CA, Papadodima SA. Forensic investigation of child victim with sexual abuse. Indian Pediatrics. 2009;46:144–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan RG. Quality evaluation of clinical records of a group of general dental practitioners entering a quality assurance programme. Br Dent J. 2001;191:436–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ireland RS, Harris RV, Pealing R. Clinical record keeping by general dental practitioners piloting the Denplan ‘Excel’ Accreditation Programme. Br Dent J. 2001;191:260–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801158a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pessian F, Beckett HA. Record keeping by undergraduate dental students: A clinical audit. Br Dent J. 2004;197:703–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4811866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole A, McMichael A. Audit of dental practice record-keeping: A PCT-coordinated clinical audit by Worcestershire dentists. Prim Dent Care. 2009;16:85–93. doi: 10.1308/135576109788634296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samadi FM, Bastian TS, Singh A, Jaiswal R. Dental records – A vital tool of forensic odontology. Medico-Legal Update. 2009;9:14–5. [Google Scholar]