Abstract

A 52-year-old patient presented with complaints of menorrhagia. Endometrial biopsy revealed simple hyperplasia of the endometrium. Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy was carried out. The ovaries looked grossly normal, but histopathology reported granulosa cell tumor of the right ovary. Granulosa cell tumors belong to the sexcord stromal category and account for approximately 2% of all ovarian tumors. We review the features and treatment of granulosa cell tumors and the importance of screening for ovarian tumors in a case of endometrial hyperplasia and delayed menopause.

Keywords: Delayed menopause, endometrial hyperplasia, granulosa cell tumor

INTRODUCTION

The average modal age of menopause is 51 years. It has changed little since centuries (classical, medieval, and modern period). Age of menopause is independent of socio-economic state, race, height, weight, and nutritional status. It is genetically programmed into the species. Only two factors have been known to accelerate menopause smoking and high altitude. Thinner women are also known to reach menopause earlier. One of the rare causes of late menopause is granulosa cell tumor of the ovary. Here, we report a case of granulosa cell tumor of ovary in a perimenopausal lady who presented with menorrhagia.

CASE REPORT

A 52-year-old multiparous woman presented with complaints of menorrhagia. On examination, uterus was found to be bulky and fornices were free. Ultrasound was suggestive of bulky uterus with thick endometrium and normal ovaries. Hysteroscopy with endometrial biopsy was performed. The hysteroscopy findings were thick endometrium and histopathology was reported as simple hyperplasia of the endometrium. Treatment options were discussed with the patient after which she opted for hysterectomy. Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingooophorectomy was performed. Grossly, the uterus and ovaries appeared normal at the time of surgery. However, the microscopic picture showed granulosa cell tumor (Call-Exner bodies) of the right ovary, left ovary being normal. Immunohistochemistry showed tumor to be positive for Inhibin. Patient recovered well after the procedure and was advised to follow-up with serum inhibin B every 3 months till 2 years and annually life long, thereafter.

DISCUSSION

Granulosa cell tumor (GCT) of the ovary is a rare neoplasm accounting for approximately 1.5-3% of all ovarian malignancies.[1] They are classified under the category of sexcord stromal tumors. They can be either juvenile (5%) or of the adult (95%) type. They may be bilateral in 5% of cases. Microscopically, GCTs are composed of granulosa cells, theca cells, and fibroblasts in varying amounts. There are four different types of ovarian sexcord tumors namely, granulosa cell tumors, fibroma, thecoma, and fibrothecoma depending upon the histological origin.

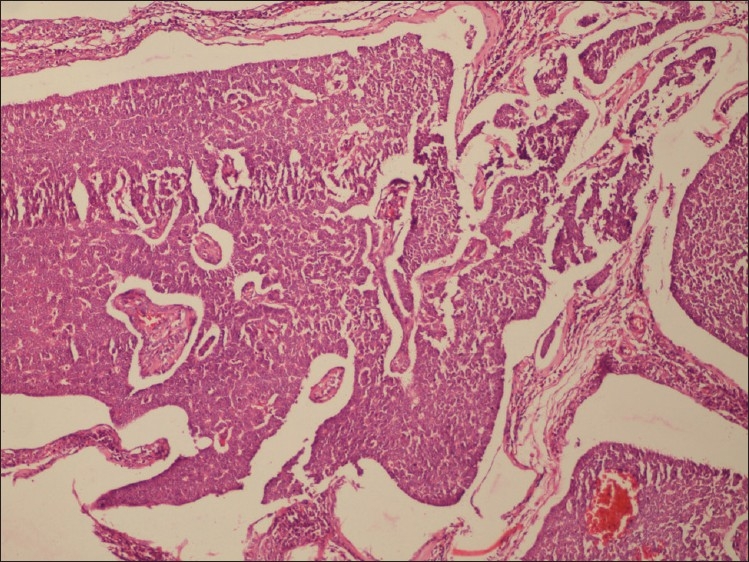

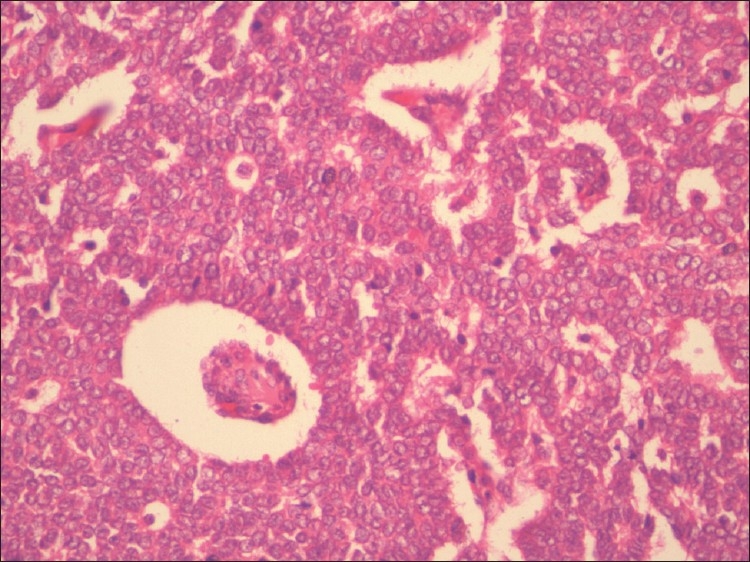

Adult GCTs have multiple histomorphologies, including well-differentiated and less welldifferentiated types. The well-differentiated group is composed of microfollicular, macrofollicular, trabecular, and insular pattern [Figure 1]. Microfollicular is the most common pattern and contains the characteristic Call-Exner bodies [Figure 2]. These bodies consist of small rings of granulosa cells surrounding eosinophilic fluid and basement membrane material. Adult GCTs showing cytoplasmic vacuoles, prominent nucleoli, mitosis, and necrosis are suggestive of aggressive behavior.[2] This tumor produces estrogen, and this is the reason for early diagnosis. The most common endocrine manifestation in the perimenopausal and menopausal age group is abnormal uterine bleeding. Upto 50% of patients develop endometrial hyperplasia[3] and another 8–33% have endometrial adenocarcinoma. Patients can also have breast tenderness and increased vaginal secretion from estrogenic stimulation of the breast and vaginal tissues, respectively. Patients are also at an increased risk of breast cancer although a direct correlation is difficult to prove. After menopause, elevated estrogen suppresses FSH and these women often do not complain of vasomotor symptoms.

Figure 1.

Macrofollicular pattern of granulosa cells

Figure 2.

Call-Exner bodies and nuclear grooves

This case highlights the fact that cases of dysfunctional uterine bleeding may be because of an estrogen secreting tumor of the ovary and hence, importance must be given to the accurate imaging of the ovaries. GCTs have a heterogeneous appearance on sonography depending on the histologic pattern. Most commonly, they appear as round to ovoid masses that are multicystic with solid components in the center or periphery.[4] Fewer cases appear as unilocular simple or complex cysts or even homogeneous solid masses. The preoperative work up should also include mammography as these women are at increased risk for breast cancer due to the excess estrogen production.

Apart from the regular tumor markers, several other tumor markers have been evaluated in patients with GCTs including Inhibin. Inhibin is a peptide hormone produced by the ovarian granulosa cells. Although Inhibin A and Inhibin B levels can both be elevated in patients with GCTs, Inhibin B levels are usually elevated in a higher proportion of these tumors.[5] Studies of Inhibin in patients with GCTs have shown that levels are elevated preoperatively and return to reference range postoperatively. Serum inhibin levels are also used for long-term follow-up of patients with lead time from elevation of inhibin to clinical recurrence being 11 months.

Granulosa cell tumors are staged surgically following the 1987 FIGO classification same as that of other ovarian carcinomas. Prognosis of GCTs generally is favorable. GCTs are considered tumors of low malignant potential. Approximately 90% of tumors are at stage I at time of diagnosis. The 10 year survival for stage I tumor in adults is 90-96%. GCTs of more advanced stage are associated with 5 and 10 years survival rates of 33-44%. Tumor stage at the time of initial surgery is the most important prognostic variable. Besides stage, Chan et al., found age younger than 50, smaller tumor size, and absence of residual disease to be statistically significant factors in predicting survival.[6]

Despite the relatively indolent nature and favorable prognosis of most GCTs, late recurrences are not a rare event even in stage I patients,[7] hence patients must be educated about the need for long-term follow-up. Surveillance for patients postoperatively consists of frequent pelvic examinations and assessment of tumor markers to detect recurrences as early as possible. Recurrences can often be treated effectively by another surgical procedure followed by chemotherapy or radiation therapy, to which some adult granulosa cell tumors have been very sensitive. Recently, aromatase inhibitors have shown promising results in the treatment of recurrent Granulosa cell tumors.[8] Currently, Anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) has been shown to be a circulating marker specifically for GCT. Its diagnostic performance seems to be very good, with a sensitivity ranging between 76 and 93%. In patients treated for GCT, AMH may be used postoperatively as marker for the efficacy of surgery and for disease recurrence.

In conclusion, a patient presenting in the perimenopausal period must be evaluated very thoroughly for possible malignancy of the genital tract and breasts. In all patients presenting with delayed menopause, the possibility of a granulosa cell tumor must be kept in mind during evaluation. Early diagnosis and treatment can lead to prolonged survival in this age group.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to acknowledge the Department of Pathology, Nowrosjee Wadia Maternity Hospital.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pectasides D, Pectasides E, Psyrri A. Granulosa cell tumor of the ovary. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:112. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kavuri S, Kulkarni R, Reid Nicholson M. Granulosa cell tumor of the ovary: Cytologic findings. Acta Cytol. 2010;54:5519. doi: 10.1159/000325176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.You XL, Yin RT, Li KM, Wang DQ, Li L, Yang KX. Clinical and pathological analysis on ovarian granulosa cell tumors. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2010;41:46770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharony R, Aviram R, Fishman A, Cohen I, Altaras M, Beyth Y, et al. Granulosa cell tumors of the ovary: Do they have any unique ultrasonographic and color doppler flow features? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2001;11:22933. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2001.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mom CH, Engelen MJ, Willemse PH, Gietema JA, ten Hoor KA, de Vries EG, et al. Granulosa cell tumors of the ovary: The clinical value of serum inhibin A and B levels in a large single center cohort. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:36572. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan JK, Zhang M, Kaleb V, Loizzi V, Benjamin J, Vasilev S, et al. Prognostic factors responsible for survival in sexcord stromal tumors of the ovary- a multivariate analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:2049. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondi-Pafiti A, Grapsa D, Kairi-Vassilatou E, Carvounis E, Hasiakos D, Kontogianni K, et al. Granulosa cell tumors of the ovary: A clinicopathological and immuohistochemical study of 21 cases. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2010;31:948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korach J, Perri T, Beiner M, Davidzon T, Fridman E, BenBaruch G. Promising effect of aromatase inhibitors on recurrent granulosa cell tumors. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:8303. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a261d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]