Abstract

Chiari type III is the rarest of the Chiari malformations and is usually associated with high morbidity and mortality. Treatment consists of primary closure of the encephalocele with or without cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) shunting. In our case, the patient was treated with ventriculoperitoneal shunt followed by excision of the encephalocele. We propose that large encephaloceles should be treated with CSF shunting prior to repair of the sac so as to achieve optimal result.

Keywords: Chiari malformation, encephalocele, hydrocephalus

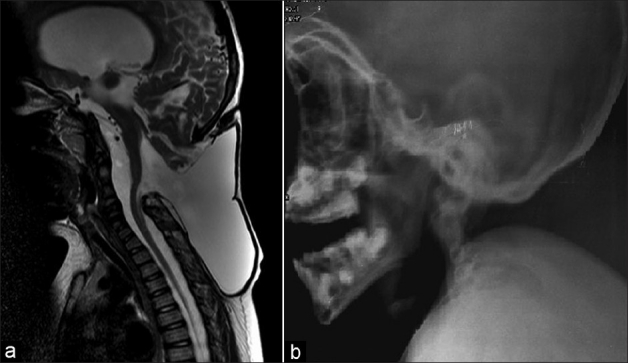

A 7-year-old boy presented with gradually increasing swelling in the occipital region since birth. There was history of delayed milestones in the form of inability to walk without support. The child was able to carry out his daily activities, but for the cosmetic deformity. Examination revealed a large 20 × 15 cm soft, fluctuant, nontransilluminant, swelling in the occipito-cervical region [Figure 1a and b]. The boy also had abnormal facies. There were no other systemic abnormalities. He had mild hypertonia of the lower limbs. MRI showed a small posterior fossa with a large occipito-cervical encephalocele extending from occiput to C4 with cerebellar tissue herniating into the sac [Figure 2a and b]. There was communicating hydrocephalus with thinned out corpus callosum. Cervical spine radiograph showed the absence of posterior elements from C1 to C4. He underwent a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt placement followed by excision and repair of the encephalocele. Intraoperatively, the encephalocele cavity was communicating with the fourth ventricle and extending inferiorly till C4. Postoperatively, he recovered well. At 1-year follow-up the child is doing well without any deficits.

Figure 1 (a,b).

Preoperative photograph showing a large swelling in the occipitocervical region

Figure 2.

(a) MRI showed a large encephalocele with herniation of cerebellar tissue into the cyst. (b) Cervical radiograph the showed absence of posterior elements from C1 to C4

Chiari type III malformation, the rarest of the chiari malformations, is characterized by a combination of occipital or a high cervical encephalocele in association with the other anomalies seen in chiari II malformation.[1] Abnormalities noted on MR imaging include encephaloceles containing varying amounts of brain tissue, ventricles, cisterns with petrous and clivus scalloping, cerebellar hemisphere overgrowth, cerebellar tonsillar herniation, deformed midbrain, hydrocephalus, corpus callosal dysgenesis, posterior cervical vertebral agenesis, and spinal cord syrinx.[2] The size of the sac, its contents, presence of hydrocephalus, infections, and other associated abnormalities are associated with bad prognosis.[3] Primary closure is the treatment of choice with cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) diversion later. However, a CSF diversion procedure may be required prior to primary closure in patients with hydrocephalus and large encephaloceles so as to achieve optimal repair. Only one patient has been reported to have undergone CSF diversion followed by surgical closure[4] as in our case.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Caldarelli M, Rea G, Cincu R, Di Rocco C. Chiari type III malformation. Childs Nerv Syst. 2002;18:207–10. doi: 10.1007/s00381-002-0579-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castillo M, Quencer RM, Dominguez R. Chiari III malformation: Imaging features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1992;13:107–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiymaz N, Yýlmaz N, Demir I, Keskin S. Prognostic factors in patients with occipital encephalocele. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2010;46:6–11. doi: 10.1159/000314051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snyder WE, Jr, Luerssen TG, Boaz JC, Kalsbeck JE. Chiari III malformation treated with CSF diversion and delayed surgical closure. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1998;29:117–20. doi: 10.1159/000028704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]