Abstract

Spontaneous spinal extradural hematoma is a rare clinical scenario which may be secondary to a variety of etiologies. Spinal epidural hematoma is an extremely rare complication in hemophiliacs. It usually runs an acute course often leading to rapid onset of neurological deficits. MR imaging is the diagnostic modality of choice and early, prompt treatment will often yield fruitful results. We report a case of spontaneous spinal EDH in a 5-year-old male child with Hemophilia B, who was managed conservatively and was doing well at last follow-up, 2 years after treatment. The authors discuss the role of factor replacement therapy vis-a-vis surgery in such a scenario.

Keywords: Hemophilia B, early intervention, MR imaging, spinal epidural hematoma

Introduction

Spontaneous spinal EDH is a rare clinical scenario, which may be secondary to variety of etiologies such as coagulopathic disorders,[1,2] lymphomas,[3] plasma cell myeloma,[4] and very rarely, following lumbar puncture. Central nervous system hemorrhages are an uncommon but severe complication of hemophilia, occurring in only 2–8% of children with hemophilia. Less than 10% of these CNS hemorrhages are intraspinal.[5] Urgent diagnosis is key to successful management as any delay can lead to rapidly progressive neurological deficits. MRI is the imaging modality of choice. Early and prompt intervention will usually result in good outcome. We report a known case of hemophilia B who presented with backache and rapidly worsening paraparesis of short duration. He recovered gradually with conservative treatment with factor IX replacement therapy with close neurological and hematological monitoring.

Case Report

A 5-year-old male child, a known case of hemophilia B for 3 years, presented at the casualty with acute pain over the lumbosacral region and rapidly worsening paraparesis of 7 days duration. There was no history of trauma or any significant drug history. There was no prior history of similar complaints. Neurological assessment revealed bilateral lower limb paresis with hypotonia and motor power of 2/5 (MRC grading), around 40% sensory impairment to all modalities of sensation from L1 dermatome below. There was no sacral sparing. The patient had urinary retention for which he was catheterized.

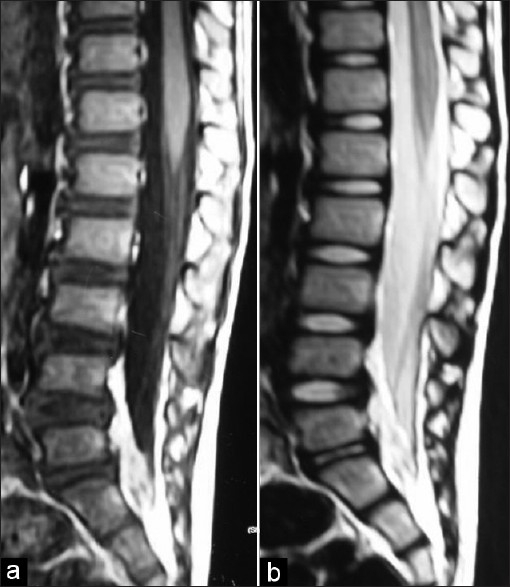

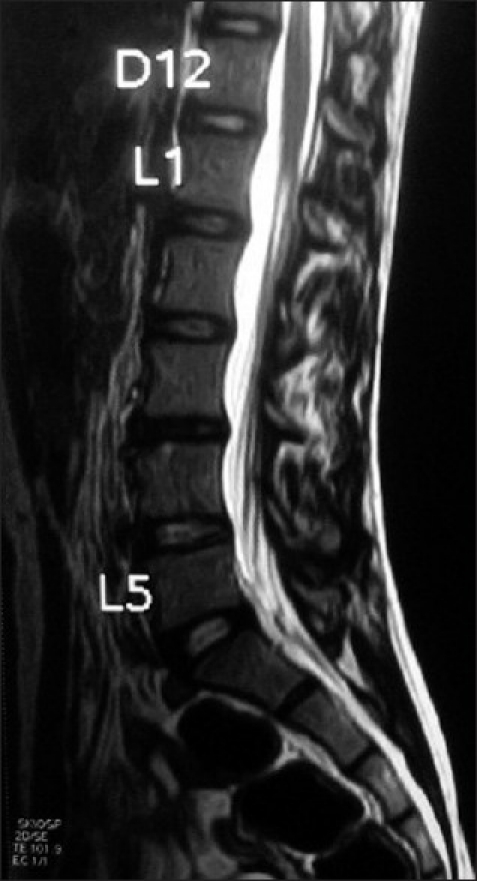

A spinal MRI done revealed a space-occupying lesion in the epidural space ventrally, extending from L4 to S2 level with heterogenously hyperintense signal on both T1 and T2 weighted images. The features were typical of acute blood [Figures 1a and b]. Hematological investigations of the patient revealed prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), normal prothrombin time, normal bleeding time, normal platelet count, and low factor IX(< 1%). In consultation with hematologist, the patient was placed on factor IX replacement therapy in a dose of 100 U/kg initially, then 50 U/kg/day for 14 days to maintain factor IX activity up to 50%. The patient gradually improved neurologically and motor power improved to 4/5 at the time of discharge. He gradually improved and at 1 month following discharge, he was self-ambulatory with no residual weakness. Sensory complaints also improved and he was catheter-free voiding urine normally. Repeat MRI revealed resolution of spinal epidural hematoma [Figure 2]. The patient was doing well at last follow-up, 2 years following treatment.

Figures 1(a-b).

T1 and T2 weighted MRI spine of the patient showing extradural hematoma from L4-S2 ventrally

Figure 2.

MRI of the patient 6 months following treatment shows resolution of hematoma

Discussion

Hemophilia is the most common hereditary bleeding disorder, with an incidence of 0.7-0.8/10,000.[6] Hemophilia A is characterized by an inherited deficiency of factor VIII while factor IX deficiency leads to hemophilia B (Christmas disease). Spontaneous spinal EDH is a rare entity in hemophiliacs, reported both in patients with hemophilia A and hemophilia B. There is no age bar for this condition as cases have been reported even in infants.[7] Spinal EDH, by and large, pursues an acute course, although a chronic course has also been reported[8] in the literature. The most common cause of death in hemophiliacs is intracranial hemorrhage; however spinal hematoma can lend the patient a severe morbidity. Patients with spontaneous spinal extradural hematoma usually present with rapidly progressive neurological deficits without any antecedent trauma. The investigation of choice remains noncontrast MR imaging, which can detect even small amounts of blood in the spinal canal. Noncontrast computed tomography is useful as an adjunct to rule out bony lesions. Early and prompt treatment is the most important factor governing the outcome of the patient. However, because of potential for severe morbidity, the optimal management remains controversial. Treatment strategies include medical line of management consisting of replacement of the deficient factors,[9] as in our case, or a combined medical–surgical approach[10] in which a decompressive procedure is performed under the cover of the deficient factor. Sheikh et al.[11] reported that aggressive factor IX replacement therapy resulted in complete neurologic recovery without the need for surgical decompression in a case of extensive spinal epidural hematoma, in a child with factor IX deficiency. Kiehna et al.[5] recently published a review regarding spinal EDH in pediatric hemophilia patients and concluded that observation and correction of coagulopathy remains a safe and effective treatment choice for patients with a stable neurological examination. They also concluded that a multidisciplinary treatment involving a pediatric hematologist, neurosurgeon, and pediatric intensive care unit to ensure timely correction of the coagulation disorder, maintenance of adequate factor levels, and close hemodynamic and neurological monitoring. Kubota et al.,[12] in a recent study, concluded that unless the neurological deficiency is progressing rapidly; nonsurgical, conservative management is safe for a spinal extradural hematoma in patients with hemophilia, rather than attempting high-risk surgical management with inappropriate coagulation status.

Conclusion

In a setting of coagulopathic disorder and rapid onset neurological deficits such as paraparesis or quadriparesis, spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma should be kept in the differential diagnosis. Prompt investigation and management of patient with coagulation factor replacement therapy can have gratifying results. Conservative therapy with replacement of deficient coagulation factor and close neurological and hematological monitoring usually result in a favorable outcome.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Balkan C, Kavakli K, Karapinar D. Spinal epidural hematoma in a patient with Hemophilia B. Haemophilia. 2006;12:437–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heer JS, Enriquez EG, Carter AJ. Spinal epidural hematoma as first presentation of Hemophilia A. J Emerg Med. 2008;34:159–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mastronardi L, Carletti S, Frondizi D, Spera C, Maira G. Cervical spontaneous epidural hematoma as a complication of non- Hodgkin's lymphoma. Eur Spine J. 1996;5:268–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00301331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayem G, Deutsch E, Roux S, Palazzo E, Grossin M, Meyer O. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma with spinal cord compression complicating plasma cell myeloma. Spine. 1998;23:2432–5. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199811150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiehna EN, Waldron PE, Jane JA. Conservative management of an acute spontaneous holocord epidural hemorrhage in a hemophiliac infant. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2010;6:43–8. doi: 10.3171/2010.4.PEDS09537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agrawal D, Mahapatra AK. Spontaneous subdural hematoma in a young adult with hemophilia. Neurol India. 2003;51:114–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noth I, Hutter JJ, Meltzer PS, Damiano ML, Carter LP. Spinal epidural hematoma in the hemophilic infant. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1993;15:131–4. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199302000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanley P, McComb JG. Chronic spinal epidural hematoma in Hemophilia A in a child. Pediatr Radiol. 1983;13:241–3. doi: 10.1007/BF00973167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narawong D, Gibbons VP, McLaughlin JR, Bouhasin JD, Kotagal S. Conservative management of spinal epidural hematoma. Pediatr Neurol. 1988;4:169–71. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(88)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meena AK, Jayalakshmi S, Prasad VS, Murthy JM. Spinal epidural haematoma in a patient with haemophilia-B. Spinal Cord. 1998;36:658–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheikh AA, Abildgaard CF. Medical management of extensive spinal epidural hematoma in a child with factor IX deficiency. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1994;10:26–9. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199402000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubota T, Miyajima Y. Spinal extradural haematoma due to haemophilia A. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:498. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.118687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]