Dear Sir,

PEHO syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive neurodegenerative disorder.[1] It was first reported in Finland and very few cases have been described from other countries.[2–5] Only one case was described from Turkey.[6] Up to now, the gene location is unknown and there is no biochemical test to confirm the diagnosis. The diagnosis is established by clinical criteria.[1] Infantile hypotonia, convulsive disorders including myoclonic jerks and infantile spasms, profound psychomotor retardation, absence or early loss of visual fixation with atrophy of optic discs and progressive brain atrophy in neuroimaging studies are necessary criteria for diagnosis.[1] Patients also have dysmorphic features like narrow forehead, short nose, open mouth, and tapering fingers. Edema of face and limbs, especially in early childhood, is an important feature of the disease. The clinical presentation of PEHO-like syndrome is similar to that of PEHO syndrome, but neuro-ophthalmologic or neuroradiologic findings are absent.[7]

The patient is a two-year-old girl and she is the first child of a nonconsanguineous 30-year-old mother and a 35-year-old father. She was born at term by normal vaginal delivery following an uncomplicated delivery. Severe hypotonia and visual inattention were evident from the first month of life. At the age of three months, flexor spasms occurring 30-40 times a day started and an electroencephalogram revealed hypsarrhythmia. She was treated with adrenocorticotrophic hormone, but after two months of seizure-free period, myoclonic and tonic seizures which were refractory to antiepileptic drugs started.

At the age of twelve months, neurological examination revealed severe psychomotor retardation, truncal hypotonia, microcephaly, and brisk tendon reflexes. She was not able to follow objects. Dysmorphic features included narrow forehead, short nose, open mouth, receding chin, prominent auricles, and tapering fingers. There was prominent edema in the face and limbs [Figure 1]. Remainder of the physical examination was normal.

Figure 1.

Prominent edema in the face and extremities of the patient

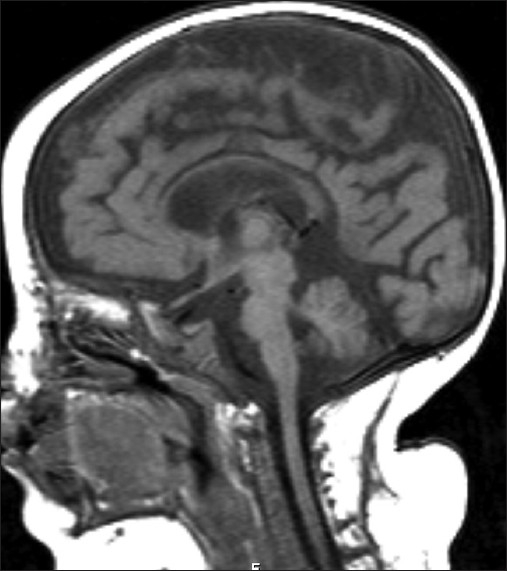

Brain magnetic resonance imaging at the age of twelve months revealed cerebral, cerebellar and brainstem atrophy [Figure 2]. Metabolic investigations including plasma and serum amino acids, urine organic acids, tandem mass spectrometry, blood lactate, pyruvate, liver function tests, serum creatine kinase, and serum uric acid were normal. Karyotype was also normal. Fundoscopy was normal at that time, but at the age of two years, optic atrophy was detected in both eyes.

Figure 2.

Cerebral T1 weighted sagittal image showing cerebral, cerebellar and brainstem atrophy

The patient is diagnosed as PEHO syndrome and she has severe psychomotor retardation, drug-resistant epilepsy and recurrent pneumonia episodes often requiring hospitalization.

The patient is a one-year-old girl and she is the first child of a nonconsanguineous parents. She was born at term by normal vaginal delivery following an uncomplicated delivery. At the age of one month, extensor spasms occurring 30-40 times a day started and an electroencephalogram revealed hypsarrhythmia. She was treated with adrenocorticotrophic hormone, but after three months of seizure-free period, myoclonic and tonic seizures started which were controlled with a combination of clobazam and vigabatrin. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging, metabolic investigations including tandem mass spectrometry, blood lactic acid, pyruvate, ammonia and urine organic acids which were done in another hospital revealed no abnormality. Karyotype was also normal.

At the age of twelve months, she was admitted to our pediatric neurology department for recurrent seizures and neurological examination revealed severe psychomotor retardation, truncal hypotonia, microcephaly, and brisk tendon reflexes. She was not able to follow objects. Dysmorphic features included narrow forehead, short nose, open mouth, receding chin, prominent auricles, and tapering fingers. There was prominent edema in the face and limbs [Figure 3]. Remainder of the physical examination was normal.

Figure 3.

Dysmorphic features including narrow forehead, short nose, open mouth, and receding chin. There was prominent edema in the face and limbs

Control brain magnetic resonance imaging at the age of twelve months revealed mild cerebral and cerebellar atrophy. Fundoscopy was normal.

The patient is diagnosed as PEHO-like syndrome and she still has resistant seizures despite combination of two antiepileptic drugs.

The diagnosis of PEHO and PEHO-like syndrome depends on the clinical and radiologic findings, because no genetic defects have been identified. Regarding the biochemical abnormalities, in patients with the PEHO syndrome, the levels of IGF-1 were found to be reduced and the levels of nitrite/nitrate were found to be markedly elevated. It was suggested that defective production of IGF-1 probably reflected the underlying neurodegeneration and the increase in NO production probably reflected the seizure activity and/or neurodegeneration.[8] The first patient fulfilled clinical criteria (hypotonia, severe psychomotor retardation, hypsarrhythmia, optic atrophy, facial and limb edema, and dysmorphic features) for PEHO syndrome. Neuroradiological findings were also compatible (cerebral and cerebellar atrophy) with this syndrome. The second patient was diagnosed as PEHO-like syndrome because neuro-ophthalmologic findings were absent and there was mild cerebral and cerebellar atrophy. The discrimination between PEHO and PEHO-like syndrome is based on neuro-radiologic and neuro-ophthalmologic findings.[7] Some investigators accepted the presence of cerebellar atrophy as the major discriminator among these two groups, rather than the other features such as optic atrophy.[9,10] Although we were not able to test IGF-1 and NO levels in our patients, both of them fulfilled the necessary clinical and radiological criteria of the diseases.

Since the diagnosis depends on the exclusion of neurodegenerative and neurometabolic disorders, all metabolic tests should be performed. The results of neuroradiologic and metabolic investigations of our patients did not reveal a specific neurodegenerative or neurometabolic disorder. Karyotypes were also normal. Clinical follow up of patients with suspected PEHO syndrome is very important. Signs like optic atrophy occur in the second year of the disease and edema of the limbs and face may be transitory.[1] In our first case, optic atrophy became evident when the case was 18 months old.

Radiological follow up is essential. Brain magnetic resonance imaging may be normal in the early stage of the disease, but as the disease progresses cerebral especially cerebellar atrophy develops. Myelination can be delayed in some cases.[11] Our cases displayed all radiological features of the disease.

Epilepsy in PEHO and PEHO-like syndrome generally starts with infantile spasms. When infantile spasms resolve, myoclonic, tonic, clonic and absence seizures start and these seizures are refractory to antiepileptic drugs.[8] There is no specific electroencephalographic abnormality for PEHO and PEHO-like syndrome. Infantile spasms in our cases started in the first months of life and the response to adrenocorticotrophic hormone was good. After a seizure-free period, seizures of different type started and they were resistant to antiepileptic drugs.

In conclusion, PEHO syndrome is a rare neurodegenerative disease. Most of the reported cases are from Finland and a few cases are reported from other countries. These were the second and third cases reported from Turkey. The syndrome should be suspected in cases with infantile spasms especially when the case has dysmorphic features and peripheral edema. Clinical follow up of patients is very important because symptoms like optic atrophy, edema and radiological findings can appear later.

References

- 1.Somer M. Diagnostic criteria and genetics of the PEHO syndrome. J Med Genet. 1993;30:932–6. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.11.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salonen R, Somer M, Haltia M, Lorentz M, Norio R. Progressive encephalopathy with edema, hypsarrhythmia, and optic atrophy (PEHO syndrome) Clin Genet. 1991;39:287–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1991.tb03027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujimoto S, Yokochi K, Nakano M, Wada Y. Progressive encephalopathy with edema, hypsarrhythmia, and optic atrophy (PEHO syndrome) in two Japanese siblings. Neuropediatrics. 1995;26:270–2. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanhatalo S, Somer M, Barth PG. Dutch patients with progressive encephalopathy with edema, hypsarrhythmia, and optic atrophy (PEHO) syndrome. Neuropediatrics. 2002;33:100–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Field MJ, Grattan-Smith P, Piper SM, Thompson EM, Haan EA, Edwards M, et al. PEHO and PEHO-like syndromes: Report of five Australian cases. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;122:6–12. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tekgul H, Tutuncuoglu S. Progressive encephalopathy with edema, hypsarrhythmia, and optic atrophy (PEHO syndrome) in a Turkish child. Turk J Pediatr. 2000;42:246–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chitty LS, Robb S, Berry C, Silver D, Baraitser M. PEHO or PEHO-like syndrome? Clin Dysmorphol. 1996;5:143–52. doi: 10.1097/00019605-199604000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riikonen R. The PEHO syndrome. Brain Dev. 2001;23:765–9. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(01)00283-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riikonen R, Somer M, Turpeinen U. Low insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) in the cerebrospinal fluid of children with progressive encephalopathy, hypsarrhythmia, and optic atrophy (PEHO) syndrome, and cerebellar degeneration. Epilepsia. 1999;40:1642–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb02051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanhatalo S, Riikonen R. Markedly elevated nitrate/nitrite levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of childrenwith progressive encephalopathy with edema, hypsarrhythmia, and optic atrophy (PEHO syndrome) Epilepsia. 2000;41:705–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein A, Schmitt B, Boltshauser E. Progressive encephalopathy with edema, hypsarrhythmia and optic atrophy (PEHO) syndrome in a Swiss child. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2004;8:317–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]