Abstract

Elongation factor P (EF-P) is an essential protein that stimulates the formation of the first peptide bond in protein synthesis. Here we report the crystal structure of EF-P bound to the Thermus thermophilus 70S ribosome along with the initiator transfer RNA N-formyl-methionyl-tRNAi (fMet-tRNAifMet) and a short piece of messenger RNA (mRNA) at a resolution of 3.5 angstroms. EF-P binds to a site located between the binding site for the peptidyl tRNA (P site) and the exiting tRNA (E site). It spans both ribosomal subunits with its amino terminal domain positioned adjacent to the aminoacyl acceptor stem and its carboxyl terminal domain positioned next to the anticodon stem-loop of the P site–bound initiator tRNA. Domain II of EF-P interacts with the ribosomal protein L1, which results in the largest movement of the L1 stalk that has been observed in the absence of ratcheting of the ribosomal subunits. EF-P facilitates the proper positioning of the fMet-tRNAifMet for the formation of the first peptide bond during translation initiation.

Elongation factor P (EF-P) is encoded by the efp gene in Escherichia coli (1) and is conserved in all eubacteria (2, 3). Previous studies suggest that EF-P is essential for cell viability in E. coli (1). Despite its stimulatory effects on peptide bond formation between ribosome-bound initiator transfer RNA N-formyl-methionyl-tRNAi (fMet-tRNAifMet) and puromycin (4) and N-acetyl-Phe tRNAPhe–primed poly(U)–directed poly(Phe) synthesis (5), EF-P is not a required component of minimal in vitro translation systems (6). EF-P is present in the cell at about 0.1 copies per ribosome, a ratio similar to that of the initiation factors (7, 8). EF-P binds stoichiometrically to each of the ribosomal subunits and to the 70S ribosome. The ratio of bound EF-P to polysomes declines with the size of polysomes, consistent with its involvement in the initial stages of protein synthesis (9). The crystal structure of EF-P revealed that the protein is composed of three β-barrel domains and has an overall L shape, reminiscent of a tRNA (10). The only known function of EF-P is a stimulatory effect in vitro on the formation of the first peptide bond.

Archaea and eukarya have a factor, known as eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A (eIF5A, previously called eIF4D), that shares sequence and structural similarity with the first two domains of EF-P (10). Like EF-P, eIF5A stimulates the formation of peptide bonds between initiator tRNA and puromycin in vitro but has no effect on the rate of poly(U)–dependent poly(Phe) synthesis (11). eIF5A is the only protein known to contain hypusine, an amino acid derived from lysine through posttranslational modification by deoxyhypusine synthase and deoxyhypusine hydroxylase (12). The hypusine modification has been identified in all analyzed archaea and eukarya but not in any eubacteria (2). However, a recent mass spectrometric analysis of endogenous EF-P from E. coli indicates a possible modification with a molecular mass of 143 daltons (9). Putative deoxyhypusine synthase–related genes have also been identified in several eubacterial species, although not in E. coli or Thermus thermophilus (13).

Alignments of the sequences of eIF5A from several species reveal that the residues surrounding the lysine residue that is modified to hypusine are extremely well conserved (12). In yeast, a K51R mutation in eIF5A, in which lysine at position 51 is replaced by arginine (14), not only inhibits hypusine formation but also cannot rescue eIF5A knockouts (15) and has reduced affinity for the ribosome (16). In addition, both eIF5A and deoxyhypusine synthase are essential in yeast (12). Like EF-Ps, the in vivo role of eIF5A in translation is still poorly understood; however, eIF5A has been linked to many other roles in the cell [reviewed in (12)].

Here, we present the crystal structure of EF-P bound to the 70S ribosome along with the initiator tRNA and a short fragment of mRNA. EF-P binds to the 70S ribosome at a site located between the binding sites for the peptidyl tRNA (P site) and the exiting tRNA (E site) and appears to stabilize the positioning of the fMet-tRNAifMet in the P site.

Overview of the structure

Crystals of the T. thermophilus 70S ribosome with bound mRNA, initiator tRNA, and EF-P diffracted to 3.5 Å resolution (17). The structure was determined by molecular replacement by using a published model of the 70S ribosome with the tRNA and mRNA ligands removed (18). A difference electron density map calculated with the use of Fobs – Fcalc amplitudes showed density for the initiator tRNA, mRNA, and EF-P, as well as density arising from movement of the L1 stalk. The initiator tRNA, mRNA, EF-P, and the repositioned L1 stalk were built, and the model was refined to an Rwork/Rfree of 25.2/30.2%.

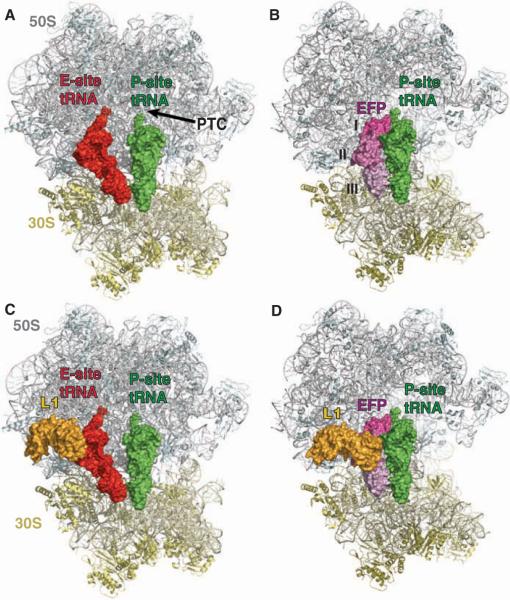

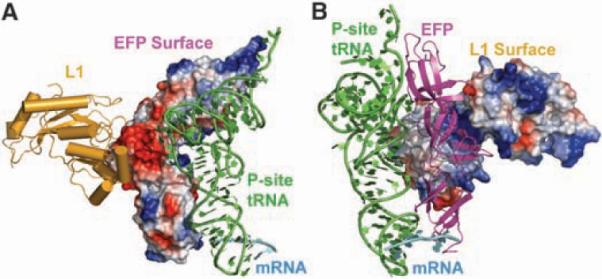

Contrary to recent biochemical studies that were interpreted to suggest that EF-P binds to the aminoacyl tRNA-binding site (A site) (9), and despite its resemblance to a tRNA, EF-P does not bind to the ribosome in a classical tRNA-binding site, but rather binds at a distinct position that is adjacent to the P-site tRNA, between the P and E sites. The L1 stalk also undergoes a major conformational change that positions the ribosomal protein L1 in the E site to interact with EF-P (Fig. 1). EF-P spans both ribosomal subunits and contacts the initiator tRNA near the anticodon stem-loop on the 30S subunit, the D-loop, and the acceptor stem on the 50S subunit (Fig. 1). Domain I of EF-P binds next to the acceptor stem of the initiator tRNA in the P site, and domain III of EF-P binds adjacent to the anticodon stem-loop of the P-site tRNA and partially overlaps the E site. Domain II of EF-P is sandwiched between domains I and II of the ribosomal protein L1. As previously noted, domain II of EF-P has an OB fold, which is characteristic for many oligonucleotide-binding proteins (10). However, the majority of its surface is negatively charged and does not interact with tRNA, but rather fits into a positively charged pocket of L1 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

The structure of EF-P bound to the ribosome. (A) Overview of the E- and P-site tRNAs bound to the 70S ribosome [coordinates were taken from the Protein DataBank (PDB) ID 2j00 and 2j01]. The 50S subunit is colored gray, the 30S subunit is colored yellow, the E-site tRNA is shown in red, and the P-site tRNA is shown in green as a surface representation. Portions of the 70S ribosome were omitted for clarity. (B) Overview of EF-P and P-site tRNA–binding in the 70S ribosome. The 50S, 30S, and P-site tRNA are colored as in (A), and EF-P is shown as a surface representation in shades of magenta to indicate the different domains (I, II, and III) of the protein. (C) Same as (A), but the ribosomal protein L1 is also shown as a surface representation in gold. (D) Same as (B), but L1 is also shown as a surface representation in gold, illustrating the large movement of L1 from its location in (C).

Fig. 2.

The interaction interfaces between EF-P, L1, and the initiator tRNA. (A) Ribosomal protein L1 (gold), the P-site tRNA (green), and the mRNA (cyan) are shown as cartoon representations, and EF-P is illustrated as an electrostatic surface, with negatively charged patches displayed in red and positively charged patches within contact of the P-site tRNA displayed in blue. (B) Same as in (A) but rotated 240° with EF-P (magenta) shown as a cartoon representation and the ribosomal protein L1 shown as an electrostatic surface, illustrating the charge complementarity between the interface of EF-P and L1.

The initiator tRNA bound in the P site displays the same conformation as that observed in the P-site tRNA of the 2.8 Å resolution structure of the T. thermophilus 70S ribosome with bound mRNA and tRNAs, which is distorted when compared with that of the crystal structure of unliganded yeast tRNAPhe (18). The superposition of the P-site tRNA from our structure onto that of the 2.8 Å resolution structure yields a root mean square deviation of less than 1.0 Å for the entire phosphate backbone; thus, even though EF-P binds adjacent to the tRNA, it does not induce any significant conformational changes.

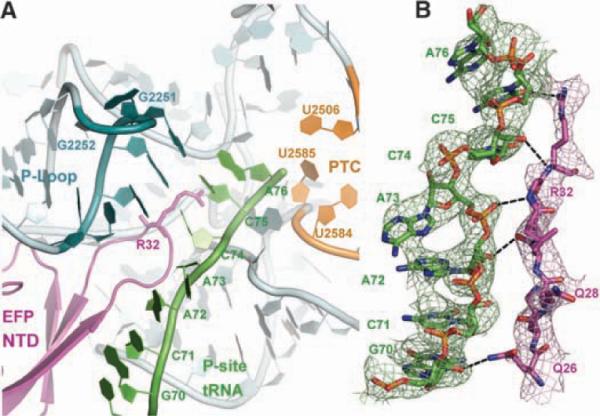

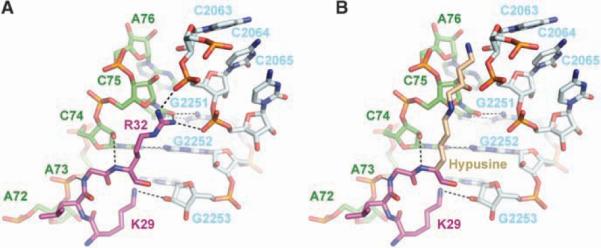

Interactions near the peptidyl transferase center (PTC)

A loop of domain I of EF-P makes numerous interactions with the CCA end of the acceptor stem of the initiator tRNA. The conserved arginine-lysine (R32) residue that is modified to hypusine in eukaryotes lies at the tip of this positively charged loop, and residues Q26 and K29 are within hydrogen-bonding distance of the 2′ hydroxyl groups of the G70 and A72 (Fig. 3). There are also additional likely hydrogen bonds between the amide nitrogens of G31 and R32 to the phosphate of A73 and the sugar of C74, respectively (Fig. 3). R32 is close to the PTC, and in one copy of the asymmetric unit, it interacts with C75 of the tRNA and the phosphates of C2064 and C2065 of the 23S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) (Fig. 4). Another residue in this loop, K29, which is well conserved in both EF-P and eIF5A, is within hydrogen-bonding distance of the ribose of G2253 in the P-loop of the 23S rRNA (Fig. 4). Residues Q28, K36, and H27 of EF-P are also within possible hydrogen-bonding distances of 2594, 2597, and 2254 of the 23S rRNA, respectively. All these interactions suggest that EF-P may play a role in correctly positioning the P-site tRNA or providing additional stabilization of the initiator tRNA in the P site. It appears that EF-P has an indirect, rather than direct, effect on peptide bond formation, because neither the initiator tRNA in the P site nor the PTC has its conformation altered by the presence of EF-P.

Fig. 3.

Interactions near the PTC. (A) Overview of the N-terminal domain (NTD) of EF-P and its interactions near the PTC of the large ribosomal subunit. The 23S rRNA is colored gray, with the exception of the P-loop (bluish green) and residues making up the PTC (orange). EF-P is colored magenta, and the acceptor arm of the P-site tRNA is shown in green. EF-P approaches the PTC of the 50S subunit but is too distant to participate directly in catalysis. (B) Unbiased difference Fourier map showing the density for the acceptor arm of the P-site tRNA (green) and the loop of the NTD of EF-P containing the R32 residue. Potential hydrogen bonds between the side chains of EF-P and the tRNA are shown as black dashes.

Fig. 4.

Hypusine homology model. (A) Close-up view of the interactions between R32 and K29 of EF-P (magenta) with the CCA end of the tRNA (green) and the 23S rRNA (light blue). Putative hydrogen bonds of R32 with the ribose of C75 and the phosphate of C2064, as well as of K29 with the ribose of G2253, are shown as black dashes. Hydrogen bonds of C74 with G2552 and of C75 with G2251 are also shown. (B) R32 was replaced by a hypothetical model structure of hypusine (light brown). In an elongated conformation, the hypusine side chain could reach into the PTC.

Even though residue R32 in T. thermophilus is close to the PTC, it is still too distant to participate directly in peptide bond formation. However, in eukaryotes, the corresponding hypusine residue has a much longer side chain than either arginine or lysine and, therefore, could extend closer to the active site (Fig. 4). It was previously suggested that the hypusine modification could stabilize the initiator tRNA in the P site (2). Because initiator tRNAs in eukaryotes are not formylated, perhaps the hypusine modification replaces the function of the formyl group of the aminoacylated initiator tRNA (19). This is further supported by in vitro experiments that show that eIF5A lacking hypusine does not stimulate methionyl-puromycin synthesis, but after in vitro modification to hypusine, the stimulatory effect is fully restored (20). Aside from its recognition by initiation factor IF2, the role of formylation of the initiator tRNA in eubacteria is unclear, as not all eubacteria require the formylase gene to support growth (21).

Interactions of domain III with the 30S subunit at the P- or E-site gate

Domain III of EF-P is well conserved in eubacteria, binds next to the anticodon stem-loop of the initiator tRNA, and partially occupies the E site of the small ribosomal subunit (Fig. 1). A loop of domain III extends toward the mRNA; however, its tip is disordered in both complexes of the asymmetric unit, which prevented us from drawing any conclusions about possible interactions between EF-P and the mRNA. Because domain III contacts only the small ribosomal subunit and is missing from eIF5A, eIF5A must bind specifically to the 60S subunit and does not span both ribosomal subunits.

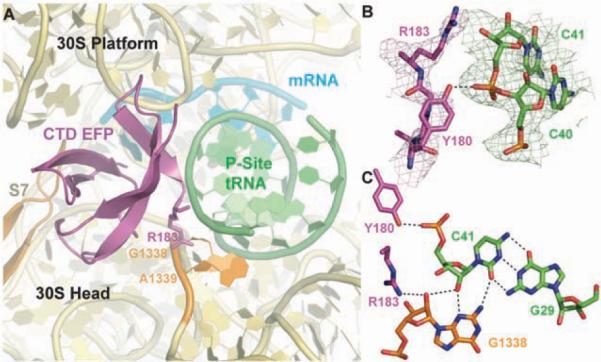

The interactions made by domain III may help to prevent premature movement of the initiator tRNA to the E site. Residues Y180 and R183 of domain III stabilize the A-minor interactions between two G·C base pairs in the anticodon stem-loop of the initiator tRNA and the bases of residues A1339 and G1338 of the 16S rRNA (Fig. 5). Because these A-minor interactions have to break during translocation, A1339 and G1338 have been proposed to function as a “gate” between the P and E sites (18). These interactions of EF-P may enhance this gate and stabilize the fMet-tRNAifMet in the P site. Although domain III is missing from eIF5A, we cannot exclude the possibility that its function is provided by another protein in eukaryotes.

Fig. 5.

Interactions between EF-P and the 30S subunit. (A) Overview of the interactions made by the P-site tRNA (green) and C-terminal domain of EF-P (magenta) with the small ribosomal subunit (rRNA, yellow; S7 protein, brown). The two key bases of the small ribosomal subunit that act as a gate between the P and E sites are colored orange. (B) Unbiased difference Fourier map showing the density for the terminal residues of EF-P and C39–C41 of the initiator tRNA. Potential hydrogen bonds between R183 and Y180 and the tRNA are illustrated as black dashes. (C) R138 of EF-P stabilizes the type II A-minor interaction between G1338 and the C41–G29 base pair of the tRNA. Putative hydrogen bonds are shown as black dashes.

Movement of the L1 stalk

The L1 stalk is a highly dynamic component of the 50S subunit and consists of three helices from the 23S rRNA (H76 to H78) and the ribosomal protein L1. Although E. coli lacking L1 is viable, ribosomes lacking L1 display only about 50% of the activity of wild-type ribosomes in vitro (22), which can be fully restored by adding purified L1 (23). The flexibility of the L1 stalk presumably accounts for its being disordered in most high-resolution structures of the ribosome. Only in the T. thermophilus 70S structures with bound tRNAs is the majority of the stalk ordered, seemingly because its interaction with the tRNA bound in the E site fixes the position of the rRNA of the L1 stalk (18, 24, 25). The superposition of the 23S rRNA from the E site–bound 70S structures of T. thermophilus with the 23S rRNA of both the Deinococcus radiodurans large ribosomal subunit and the E. coli 70S reveals a 30° rotation of the L1 stalk toward the E site upon binding of a tRNA into the E site [reviewed in (26)].

An even larger movement of the L1 stalk has been observed by cryo–electron microscopy (cryo-EM) studies of ribosomes with stalled EF-G or eEF2. These complexes capture the ribosome in a ratcheted state, in which the small ribosomal subunit is rotated counterclockwise with respect to the large ribosomal subunit. The guanosine triphosphatase–associated center of the large ribosomal subunit changes its conformation, and the L1 stalk dramatically moves toward the E site. The L1 stalk movement is larger than the 30° motion observed between the different crystal structures. The additional motion, about the base of helix H76 of the 23S rRNA, enables the L1 stalk to interact with a tRNA bound in the hybrid P/E position, which suggests an active role for the L1 stalk in tRNA translocation and release of the E site–bound tRNA (27–29).

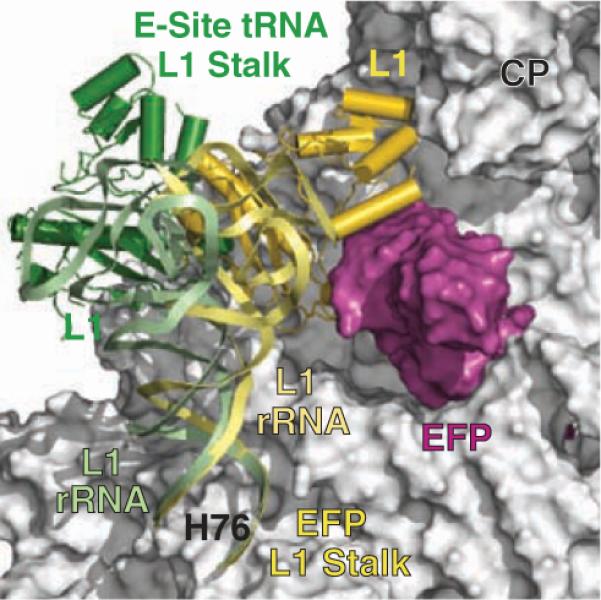

The structure of the 70S ribosome with EF-P bound exhibits the largest movement of the L1 stalk seen in a crystal structure (Fig. 6 and movie S1). Its movement into the E site in the presence of EF-P is even larger than that observed in the structure of T. thermophilus 70S ribosome with a tRNA bound in the E site. Without any disruption of the protein-RNA interface, the L1 stalk is bent and rotated at helix H76 to reposition the ribosomal protein L1 into the E site. With the exception of the repositioning of the L1 stalk, no other major conformational change is observed within the ribosome. The slight differences in the orientation of the subunits compared with the 2.8 Å structure of the T. thermophilus 70S ribosome with bound mRNA and tRNA (18) are within the variations seen between the two structures of the 70S ribosome in the asymmetric unit.

Fig. 6.

Movement of the L1 stalk. The L1 stalk from the structure of the 70S ribosome with bound EF-P is shown in gold, and the 70S structure from T. thermophilus 70S ribosome with a bound E-site tRNA (PDB ID 2j01) is shown in green. The superposition was based on the entire 23S rRNA between the 70S structures, excluding the L1 stalk. The large ribosomal subunit (gray) and EF-P (magenta) are shown as surface representations. CP indicates the central protuberance of the large ribosomal subunit.

The observed movement of the L1 stalk in the EF-P complex with the 70S ribosome appears relevant to the stalk movement associated with translocation. Both cryo-EM and single-molecule studies suggest that the L1 stalk reaches all the way to the P-site tRNA in its P/E hybrid state before translocation concurrent with the counterclockwise rotation of the small ribosomal subunit (28, 30–32). This interaction between the stalk and the P-site tRNA persists through translocation of the tRNA to the E site until its release from the ribosome. The rRNA of the L1 stalk interacts with bases at the ends of the T- and D-loops of the E-site tRNA (18). If the same interactions exist between the stalk and the P-site tRNA, the stalk would have to move even farther into the E site than is observed in our EF-P–bound 70S ribosome structure in order to reach the P site or hybrid P/E site tRNA, which may only be achievable with the ratchet motion. The motion of the L1 stalk toward the E site seen in our structure clearly is not coupled to the counterclockwise rotation of the small subunit, as has been observed during translocation, perhaps because the distance it moves is less and it interacts through protein L1, rather than the stalk rRNA.

Because EF-P is completely buried within the ribosome, the L1 stalk must move to allow its dissociation and to make the E site accessible for the translocation of the initiator tRNA. Previous biochemical experiments have demonstrated that the initiator tRNA has a lower propensity to move into the P/E hybrid state than deacylated elongator tRNAs and that the rate of EF-G catalyzed translocation of the initiator tRNAfMet is slower (by several factors) than with the elongator tRNAMet (31, 33). Release of EF-P from the ribosome could be before or coupled with the EF-G catalyzed translocation of the deacylated initiator tRNA into the E site.

Correct positioning of the initiator tRNA

The 3.5 Å resolution structure of EF-P bound to the 70S ribosome in complex with the initiator tRNA provides a structural basis for understanding the role that EF-P plays in promoting the formation of the first peptide bond, the final step in the initiation phase of protein synthesis. During initiation, only the initiator tRNA, which is distinctly different from elongator tRNAs [reviewed in (34)], occupies the P site and no deacylated tRNA is bound in the E-site tRNA. All the interactions between EF-P and the fMet-tRNAifMet are not specific for the initiator tRNA; this suggests that EF-P binding to the ribosome is not restricted to the initiator tRNA, consistent with previous biochemical data (5). A recent publication concludes that eIF5A also forms nonspecific contacts with tRNAs in yeast, because it stimulates the first, as well as subsequent, peptidyl-transfer reactions during protein synthesis (20). In our current structure, the positions of the domains 1 and 2 of EF-P that are homologous to eIF5A exclude the simultaneous binding of eIF5A and a tRNA in the E site.

The structure presented here suggests that a major role of EF-P is to help correctly orient the entire P-site tRNA and to restrict the mobility of the aminoacyl arm in order to facilitate peptide bond formation. Similar functions have been attributed to ribosomal proteins L16 and L27 for the correct positioning of the A-site tRNA (35). Although ribosomes lacking L16 are severely impaired in peptide bond formation (36), the first peptide bond formation can still be stimulated by EF-P (37). The interactions observed between L16 and the A-site tRNA suggest that it stabilizes the binding of the A-site tRNA (35). The presence of L27 stimulates the reaction of puromycin with fMet-tRNAifMet by the same magnitude as EF-P (38); however, in contrast to EF-P, L27 also affects all subsequent peptidyl transfer reactions. Ribosomes lacking L27 are impaired in binding of the A-site tRNA (38), and removal of even just the first three amino acids reduces the rate of peptide bond formation (39). The high-resolution structure of the 70S ribosome with tRNAs bound in the A and P sites reveals interactions between the N terminus of L27 and the CCA tail of both the P- and A-site tRNAs (35). The N-terminal residues of L27 are disordered in the structure presented here, perhaps because of the absence of an A-site tRNA. The stabilization of the CCA tail of the A-site tRNA by the N terminus of L27 could explain the increased affinity of the A site for aminoacylated tRNA in the presence of L27, as well as the stimulatory effect of L27 on protein synthesis (38). Similarly, the stabilization of the CCA tail of the P-site tRNA by EF-P could explain the increased puromycin reactivity of fMet-tRNAifMet. Whether this stabilization function is subsequently taken up by the nascent polypeptide chain is unknown.

The initiation of translation in eubacteria is a multistep process that involves the formation of several intermediate complexes with different compositions and conformations (40). Structures of initiation complexes derived from cryo-EM studies have revealed that, during the process of initiation, the fMet-tRNAifMet adopts several different conformations on both the 30S subunit and the 70S ribosome before finally reaching its proper position in the P/P state (40–42). By stabilizing the P/P state of the initiator tRNA, EF-P could shift initiation toward the first elongation step of protein translation.

Conclusions

The structure of the EF-P complex with the 70S ribosome reveals the detailed interactions between EF-P and the 70S ribosome, initiator tRNA, and the ribosomal protein L1. The essential role of EF-P in the cell may be to correctly position the fMet-tRNAifMet in the P site for the first step of peptide bond formation by making several interactions with the backbone of the tRNA. Because eIF5A shows high structural similarity to EF-P, the conclusions drawn for EF-P likely also apply to eIF5A's role in the rate enhancement of the formation of the first peptide bond in eukarya.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the Advanced Photon Source beamline 24-ID and at the National Synchrotron Light Source beamline ×29 for help during data collection and the staff at the Center for Structural Biology facility at Yale University for computational support. We also thank I. Lomakin for providing us with methionyl-tRNA synthetase (MetRS) and U. L. RajBhandary and K. H. Nierhaus for the overexpression plasmids of methionyl-tRNA formyltransferase (MTF) and the initiator tRNA, respectively. This work was supported by NIH grant GM22778 (to T.A.S.). The coordinates for both copies of the 70S in the asymmetric unit have been deposited in the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank with accession numbers 3HUW, 3HUX, 3HUY, and 3HUZ. T.A.S. owns stock in and is on the advisory board of Rib-X Pharmaceuticals, Inc., which does structure-based drug design targeted at the ribosome.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/325/5943/966/DC1

References and Notes

- 1.Aoki H, Dekany K, Adams SL, Ganoza MC. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:32254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kyrpides NC, Woese CR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganoza MC, Kiel MC, Aoki H. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002;66:460. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.460-485.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glick BR, Ganoza MC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1975;72:4257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.11.4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganoza MC, Aoki H. Biol. Chem. 2000;381:553. doi: 10.1515/BC.2000.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimizu Y, et al. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:751. doi: 10.1038/90802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole JR, Olsson CL, Hershey JW, Grunberg-Manago M, Nomura M. J. Mol. Biol. 1987;198:383. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90288-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.An G, Glick BR, Friesen JD, Ganoza MC. Can. J. Biochem. 1980;58:1312. doi: 10.1139/o80-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aoki H, et al. FEBS J. 2008;275:671. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanawa-Suetsugu K, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:9595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308667101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benne R, Brown-Luedi ML, Hershey JW. J. Biol. Chem. 1978;253:3070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zanelli CF, Valentini SR. Amino Acids. 2007;33:351. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0533-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brochier C, Lopez-Garcia P, Moreira D. Gene. 2004;330:169. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Single-letter abbreviations for the amino acid residues are as follows: A, Ala; C, Cys; D, Asp; E, Glu; F, Phe; G, Gly; H, His; I, Ile; K, Lys; L, Leu; M, Met; N, Asn; P, Pro; Q, Gln; R, Arg; S, Ser; T, Thr; V, Val; W, Trp; and Y, Tyr.

- 15.Schnier J, Schwelberger HG, Smit-McBride Z, Kang HA, Hershey JW. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991;11:3105. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.6.3105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jao DL, Chen KY. J. Cell. Biochem. 2006;97:583. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 18.Selmer M, et al. Science. 2006;313:1935. doi: 10.1126/science.1131127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hershey JW, Smit-McBride Z, Schnier J. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1990;1050:160. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(90)90159-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saini P, Eyler DE, Green R, Dever TE. Nature. 2009;459:118. doi: 10.1038/nature08034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newton DT, Creuzenet C, Mangroo D. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:22143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subramanian AR, Dabbs ER. Eur. J. Biochem. 1980;112:425. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb07222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sander G. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:10098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korostelev A, Trakhanov S, Laurberg M, Noller HF. Cell. 2006;126:1065. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yusupov MM, et al. Science. 2001;292:883. doi: 10.1126/science.1060089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korostelev A, Noller HF. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007;32:434. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spahn CM, et al. Cell. 2004;118:465. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valle M, et al. Cell. 2003;114:123. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00476-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Connell SR, et al. Mol. Cell. 2007;25:751. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connell SR, et al. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:910. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cornish PV, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:2571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813180106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fei J, Kosuri P, MacDougall DD, Gonzalez RL., Jr. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:348. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dorner S, Brunelle JL, Sharma D, Green R. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:234. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laursen BS, Sorensen HP, Mortensen KK, Sperling-Petersen HU. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2005;69:101. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.1.101-123.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Voorhees RM, Weixlbaumer A, Loakes D, Kelley AC, Ramakrishnan V. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:528. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore VG, Atchison RE, Thomas G, Moran M, Noller HF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1975;72:844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.3.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aoki H, Adams SL, Turner MA, Ganoza MC. Biochimie. 1997;79:7. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(97)87619-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wower IK, Wower J, Zimmermann RA. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:19847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maguire BA, Beniaminov AD, Ramu H, Mankin AS, Zimmermann RA. Mol. Cell. 2005;20:427. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simonetti A, et al. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009;66:423. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8416-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allen GS, Zavialov A, Gursky R, Ehrenberg M, Frank J. Cell. 2005;121:703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simonetti A, et al. Nature. 2008;455:416. doi: 10.1038/nature07192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.