Abstract

Background

There is little direct data describing the outcomes and recurrent vascular morbidity and mortality of stroke survivors from low and middle income countries like Pakistan. This study describes functional, cognitive and vascular morbidity and mortality of Pakistani stroke survivors discharged from a dedicated stroke center within a nonprofit tertiary care hospital based in a multiethnic city with a population of more than 20 million.

Methods

Patients with stroke, aged > 18 years, discharged alive from a tertiary care centre were contacted via telephone and a cross sectional study was conducted. All the discharges were contacted. Patients or their legal surrogate were interviewed regarding functional, cognitive and psychological outcomes and recurrent vascular events using standardized, pretested and translated scales. A verbal autopsy was carried out for patients who had died after discharge. Stroke subtype and risk factors data was collected from the medical records. Subdural hemorrhages, traumatic ICH, subarachnoid hemorrhage, iatrogenic stroke within hospital and all other diagnoses that presented like stroke but were subsequently found not to have stroke were also excluded. Composites were created for functional outcome variable and depression. Data were analyzed using logistic regression.

Results

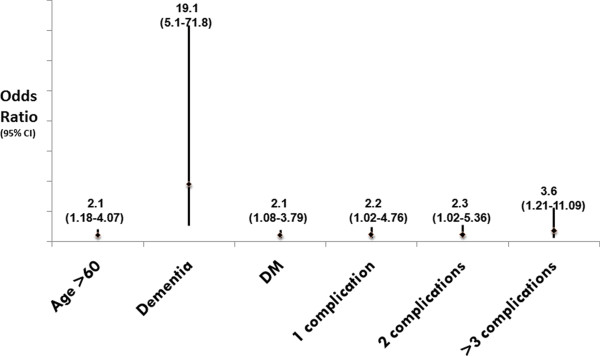

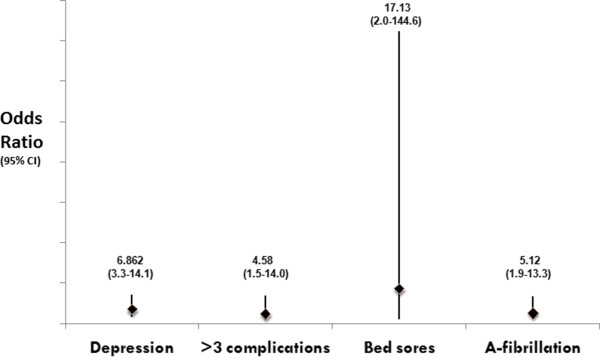

309 subjects were interviewed at a median of 5.5 months post discharge. 12.3% of the patients had died, mostly from recurrent vascular events or stroke complications. Poor functional outcome defined as Modified Rankin Score (mRS) of > 2 and a Barthel Index (BI) score of < 90 was seen in 51%. Older age (Adj-OR-2.1, p = 0.01), moderate to severe dementia (Adj-OR-19.1, p < 0.001), Diabetes (Adj-OR-2.1, p = 0.02) and multiple post stroke complications (Adj-OR-3.6, p = 0.02) were independent predictors of poor functional outcome. Cognitive outcomes were poor in 42% and predictors of moderate to severe dementia were depression (Adj-OR-6.86, p < 0.001), multiple post stroke complications (Adj-OR-4.58, p = 0.01), presence of bed sores (Adj-OR-17.13, p = 0.01) and history of atrial fibrillation (Adj-OR-5.12, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Pakistani stroke survivors have poor outcomes in the community, mostly from preventable complications. Despite advanced disability, the principal caretakers were family rarely supported by health care personnel, highlighting the need to develop robust home care support for caregivers in these challenging resource poor settings.

Background

Non communicable diseases including stroke are the leading killers in low and middle income countries like Pakistan [1]. A cross-sectional survey from a multiethnic transitional Pakistani community showed that almost a quarter of the respondents had suffered a cerebrovascular event (either a stroke or a Transient Ischemic Attack [TIA]) [2]. Thus, there is a need to generate regionally specific data from these regions to formulate effective management strategies for stroke survivors.

There are studies done in developed countries exploring the functional and cognitive outcomes of stroke [3-5]. Data from Pakistan is restricted to a few hospital based studies that have reported mortality and acute complications [6-8], but nothing is known of the post hospital outcomes of stroke survivors.

There are reasons to suspect that outcomes from stroke in developing countries like Pakistan may be sufficiently different from the developed world to merit investigation. Stroke etiology is different--intracranial disease being more common [9-12], intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) constitutes a higher proportion of strokes; patients are younger and ethnically distinct. A recent study has highlighted this regional difference in stroke outcomes and mortality reported in various stroke trials [13].

Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to report the functional, cognitive and psychological outcomes of stroke survivors after discharge. Secondary objective was to assess the frequency of recurrent vascular events in this population.

Methods

Study design and setting

This is a cross-sectional study. Patients were identified from the Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH) Karachi, Pakistan. This is a 650-bed, internationally accredited tertiary care hospital that caters to the needs of a large multi-ethnic urban population. The hospital has a dedicated stroke unit run by trained nursing staff and neurologists that deals with 600 plus patients annually.

Case ascertainment/enrollment strategies

Men and women aged ≥ 18 years, with acute stroke during the study period (January, 2010 to December, 2010) were eligible. All discharges from the stroke neurology service were identified from the medical record section using ICD code 430-438 and the relevant stroke pathways.

Acute stroke was defined by the WHO definition as "rapidly developing clinical signs of focal (at times global) disturbance of cerebral function, lasting more than 24 h or leading to death with no apparent cause other than that of vascular origin". The diagnosis was supported by either a Computed Tomography scan or Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

All the discharges were contacted for interview. Those with whom a telephonic contact could be established within 1-12 months of their index stroke and who gave consent to a verbal interview were enrolled in the study. In those who could not give consent directly, or were aphasic, surrogate consent was sought for interview and primary surrogate caregivers reported on the patient's status.

Those who had died of their index stroke during hospital stay were excluded from this study. Subdural hemorrhages, traumatic ICH, iatrogenic stroke within hospital and all other diagnoses that presented like stroke but were subsequently found not to have stroke were also excluded.

Data collection instruments

A structured telephonic interview was carried out at 1-12 months post discharge. The questionnaire (Additional file 1) had been translated into Urdu using a translation/back-translation procedure to ensure clarity and consistency. It collected data regarding outcomes and recurrent vascular events since discharge. For patients who had died during this time, a verbal autopsy questionnaire was administered to determine the proximate cause of their death [14]. A trained research officer (physician) established telephonic contact and carried out the interviews. Once the telephonic interviews had been carried out, medical records of these patients were accessed, for information on demographics, stroke subtype and risk factors (Additional file 1).

The following scales were used for assessing the outcomes. For functional Outcome Modified Rankin Score (mRS) and Barthel Index (BI) was used. For depression Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI) with direct questioning was used (for surrogate responders), and for dementia we used the Blessed Dementia Scale (BDS). Screening for recurrent stroke was done using a set of questions based on the Stroke Symptom Questionnaire. Those who had been labeled by a physician as having a recurrent stroke or myocardial infarction (MI) were also included amongst those with recurrent events. Details of our data collection instruments are contained in Additional file 1 along with references of the instruments used.

The protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Aga Khan University Hospital (ERC #: 1541-Neu-ERC-2010). Verbal informed consent was taken from all respondents and or their legal surrogate respondent prior to interview since this was a telephonic interview. Written consent could not be taken since these participants were identified via medical record discharges and contacted via phone. The interview contents/form/script were reviewed and approved by the committee and thus verbal consent was approved.

Data analysis

Reported stroke prevalence and complications of stroke has been ascertained through the literature and found to be 21% [2]. We used the figure of 0.21 for prevalence of exposure, along with 80% power, 0.05 significance level, 5% bond on error, and 20% adjustment for non-response rate give the sample size of 309.

Analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 11.5. Initially descriptive statistics and frequencies were generated. Later data were analyzed using logistic regression. In inferential statistics, continuous variables were checked for their linearity, by doing quartile analysis. Dummy variables were created for variables with more than two categories and the reference group for each variable was defined as the category with the minimal risk for functional, cognitive and psychological outcomes associated with stroke, using previous studies.

Composites were created for functional outcome variable and depression. Poor functional outcome was defined as a composite of mRS > 2 and BI ≤ 90. Depression was labeled if Beck's score was > 10 for those patients who had provided information themselves. For those who had surrogate responders, if at least three of the following four symptoms were reported to be present in the patient, he or she was labeled depressed--anger, flat affect, crying spells, and sleeplessness/low appetite. Score of 6-12 was taken as moderate and > 12 as severe dementia on BDS.

A composite variable of recurrent stroke was generated with physician confirming stroke as outcome or if the patient reported permanent neurological deficits (hemiparesis, hemianopsia, monocular blindness, facial deviation or dysphagia, dysarthria). Physician report of angina or MI was also added to the recurrent stroke variable to form a composite of recurrent vascular event.

Multicolinearity was checked among all the independent variables. A univariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the (crude) association of each independent factor with all three outcomes (Additional file 1). Biological significance and a value of p value 0.25 were considered as criteria for a variable to be significant in univariate analysis. Biologically plausible interactions among variables and confounding were also checked. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was done and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) were calculated (Additional file 1).

Results

Data was collected from patients discharged from AKUH stroke service between January and December, 2010. During this period 650 patients were admitted with acute cerebrovascular event. Subdural hemorrhages (n = 21) and in-hospital expiries (n = 45) were excluded. All the other stroke patients/surrogate caregivers were then contacted for telephonic interviews over a period of 3 months from November 1st to January 31st. Three hundred and nine patients/their surrogates consented and were included in the study. Median time from onset of stroke to outcome assessment was 5.5 months.

Demographic and stroke characteristics are described in Table 1. Of the 309 patients included, 62.1% were women. Mean age was 61.75 years (IQR 21-90). Of the 271 patients alive at the time of follow-up, all except one were being taken care of at home, and mostly (56.3%) by family members. None of the patients were in institutions or rehabilitation centers despite the disability status.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study subjects

| Characteristic | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 117 | (37.9) |

| Female | 192 | (62.1) |

| Age | ||

| ≤ 60 | 150 | (48.5) |

| > 60 | 159 | (51.5) |

| Type of stroke (n = 309) | ||

| Ischemic | 241 | (78) |

| Hemorrhagic | 68 | (22) |

| TOAST (n = 241) | ||

| Large Artery | 109 | (35.3) |

| Cardioembolic | 41 | (13.3) |

| Small artery Lacune | 55 | (17.8) |

| Others | 36 | (11.6) |

| Risk Factors (n = 309) | ||

| HTN | 288 | (93.2) |

| Dyslipidemia | 223 | (72.2) |

| DM | 178 | (57.6) |

| Obesity (BMI > 25) | 124 | (40.1) |

| CAD | 110 | (35.6) |

| Smoking/chewed tobacco | 60 | (19.4) |

| Intracranial atherosclerosis | 85 | (28.4) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 37 | (12) |

| Extracranial Carotid stenosis | 21 | (6.8) |

| Depression/Anxiety | 18 | (5.8) |

| Prior TIA or stroke | 52 | (16.8) |

| EF < 30% | 19 | (6.1) |

| Dead (n = 309) | 38 | (12.3) |

| Care being given (n = 271) | ||

| At home | 270 | (99.6) |

| Readmitted to hospital | 1 | (0.4) |

| Care provision arrangements (n = 270) | ||

| Independent | 91 | (33.7) |

| Family member | 152 | (56.3) |

| Professional Nursing | 24 | (8.9) |

| Non professional help | 3 | (1.1) |

Majority of the strokes were ischemic (78%). Of these, large artery atherosclerotic disease was the predominant etiologic subtype (35.3%). Hypertension was the commonest risk factor (93.2%), followed by dyslipidemia (72.2%), diabetes (57.6%) and obesity (40.1%).

Forty five (6.9%) of the 650 total patients had died during the hospital admission period. Of the remaining, 309 (51%) could be contacted. Thirty eight of these (12.3%) had died at the time of outcome assessment. Of these hemorrhagic strokes accounted for 26% of index strokes, while the rest were ischemic (12 were partial anterior circulation strokes, 10 were posterior circulation and 6 were lacunar strokes). Verbal autopsy revealed the cause of death as vascular (stroke, MI or both) in 78% of these patients, with recurrent stroke being responsible for 65% of these mortalities. In almost one third of the patients (31.5%) preventable complications, mostly infections related to stroke were important contributors to mortality and in four patients these were the main cause of death as presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Stroke outcomes

| Outcome variable | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Mortality | 38 | (12.3) |

| Vascular death | 30 | (78.9) |

| Recurrent CVA | 16 | (53.3) |

| Myocardial infarction | 5 | (16.7) |

| Both | 9 | (30.0) |

| Stroke related complications | 12 | (31.5) |

| Infections | 8 | (21) |

| Seizures | 3 | (7.9) |

| Others | 1 | (2.6) |

| Post stroke Complications | 176 | (64.9) |

| Pain | 126 | (46.5) |

| Constipation | 91 | (33.6) |

| UTI | 43 | (15.9) |

| Pneumonia | 14 | (5.2) |

| Other infections | 11 | (4.1) |

| Seizures | 20 | (7.4) |

| Bedsores | 17 | (6.3) |

| DVT/PE | 4 | (1.5) |

| Functional Outcomes | ||

| Modified Rankin Score (n = 271) | ||

| mRS ≤ 2 | 174 | (64.2) |

| mRS > 2 | 97 | (35.8) |

| Barthel Index (n = 271) | ||

| Barthel Index 0-30 | 43 | (15.9) |

| Barthel Index35-60 | 31 | (11.4) |

| Barthel Index 65-90 | 41 | (15.1) |

| Barthel Index 95-100 | 156 | (57.6) |

| Cognitive Outcomes (n = 271) | ||

| None BD = 0 | 31 | (11.4) |

| Mild BD 1-5 | 126 | (46.5) |

| Moderate BD 5.5-12 | 77 | (28.4) |

| Severe BD > 12 | 37 | (13.7) |

| Psychological Outcomes n = 271) | ||

| Depressed | 57 | (21) |

| Recurrent Vascular Events (n = 271) | 66 | (24.4) |

| Recurrent Stroke | 62 | (22.9) |

| MI/angina | 9 | (3.3) |

When we look at long term mortality according to stroke subtype we find that 9/38 (23%) of ICH patients and 29/38 (76%) ischemic stroke patients died. Of ICH patients, which are hypertensive basal ganglia ICH, 9/64 (14%) died, and of ischemic stroke 29/245(11.8%) died. When we look at how ischemic stroke subtype by TOAST criteria affects mortality in this group, mortality was as follows: Large Artery Atherosclerosis 11/98 (11.2%), Lacunes 4/51 (7.8%), Cardioembolic stroke 9/32 (28%), unspecified 4/30 (13%), there were no mortalities in the 'other specified' group.

Of the 271 patients alive at the time of interviews, 64.9% reported at least one complication since discharge. Pain was the commonest complication present in 126 (46.5%) patients followed by constipation (33.6%) and urinary tract infection (15.9%).

Of those alive, 34.8% had moderate to severe disability defined as mRS > 2. BI indicated that 57.6% were independent and 15.9% were severely disabled (BI ≤ 30).

When a composite of mRS > 2 and BI ≤ 90 was taken, 51.1% of the patients had poor functional outcomes. Univariate analysis for predictors of poor outcome can be reviewed in our on-line supplement (Additional file 1). The following factors were independently associated with the odds of a poor outcome, older age (OR = 2.1, CI-1.18-4.07), Diabetes (2.1, 1.08-3.79), dementia (19.1, 5.1-71.8), post discharge complications and their increasing multiplicity (3.6, 1.21-11.09) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Poor Functional Outcome: Age, Dementia, Diabetes and post stroke complications were associated with poor functional outcomes.

Moderate to severe dementia defined as BDS score of more than 5 was found in 114 (42.1%) of the 271 patients alive at the time of follow-up. Moderate to severe dementia was more likely in patients who were depressed (OR = 6.86, CI = 3.3-14.1), had 3 or more post stroke complications (4.58, 1.5-14), had bedsores (17.137, 2.0-144.6), and had atrial fibrillation (5.12, 1.9-13.3) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Moderate to Severe Dementia: Depression, post stroke complications, bedsores and atrial fibrillation uA-Fibrillation) was associated with moderate to severe dementia.

Overall, 57 of the 271 surviving patients (21%) were depressed. When depression was evaluated, people with moderate to severe dementia were 16.6 times more likely to be depressed.

Sixty six (24.4%) of the 271 patients alive at the time of follow-up reported recurrent vascular events (stroke, MI or both). Stroke was the most common recurrent event (62/271, 22.9%), making up 93% of recurrent events. Of the recurrent strokes, 37 had been confirmed by physicians.

Discussion

We found that within a median of 5.5 months after discharge at least one third of stroke survivors in Pakistan had either died due to vascular causes or suffered a recurrent vascular event usually a stroke. Despite sustained disability the patients were homebound and cared for by family members with infrequent health personnel support. Poor functional outcome was associated with patient characteristics like old age, Diabetes, CAD, atrial fibrillation, stroke subtype mainly cardioembolic and medically preventable events like post stroke complications and their increasing multiplicity. About half the survivors had moderate to severe dementia and a quarter were depressed.

Our in-hospital mortality is comparable to Western figures with around 6% patients dying during index hospitalization for stroke [15]. We report a 12% all cause mortality following hospital discharge at a median of 5 months. A large inter-study variability exists in international literature (Additional file 1) with 30 day mortality ranging between 5% and 25% [16-21] and one year mortality of 17-24% [16-20]. Regional data reports a much higher 28 day case fatality of 29.8% and 41% [22,23]. When we look at ischemic stroke subtypes and mortality, we find that cardioembolic strokes result in the greatest mortalities in this study, which is comparable to what is reported in the literature. Often the outcome is better in lacunar strokes than non-lacunar strokes [24-28]. However, while making these inferences and the ones that follow, caution must be applied as our study is a cross sectional one and a prospective cohort design would better reflect outcomes.

Around one half of our patients had poor functional outcomes based on mRS and BI. Studies from neighboring India report a 38.5% moderate to severe disability in their stroke survivors based on mRS [22]. Spain reports 37.7% functional dependence based on mRS [3]. Compared to these figures, our functional outcomes are worse. Predictors of poor functional outcomes in our study were older age, dementia and presence of post stroke complications which are consistent with what has been reported in other studies [29-32].

Pooled data from 14 studies on acute stroke reports a 21.7% prevalence of depression post stroke [33] which is comparable to our rate of 21%. Similarly, moderate to severe dementia and its predictors (old age and atrial fibrillation) were comparable to reported rates [34]. Of note was the strong association seen between depression and moderate to severe dementia (OR-16.6) which has also been previously reported [35]. One mechanism suggested for this association is stroke resulting in fronto-subcortical dysfunction that gives rise to depressive symptoms as well as dementia [36].

A quarter of our surviving patients suffered from recurrent vascular events mostly strokes after discharge at a median of 5.5 months post discharge. This figure is much more than what is reported from other studies from around the world with 1 year rates in the range of 5.8-13.3% [17,19,37] (Additional file 1). A potential explanation for this high stroke recurrence rate is the high number of patients with intracranial atherosclerotic disease (ICAD) (35%) in our sample. ICAD is known to have the highest rate of recurrent stroke of around 14% per year [38].

Our study is the first systematic investigation of the state of stroke survivors in a low and middle income country like Pakistan. Its strengths are its comprehensive approach, its coverage and access to all patient and uniformity of acute care. The interviewer was a single trained physician following a tested refined questionnaire, with internationally standardized tools of assessment [39-54].

There are several limitations. First and foremost, we were unable to contact nearly half the patients who were discharged alive. This could have skewed our results in either direction. Secondly, this is a single centre study and the care that these patients received may bias towards better functional outcomes. Thirdly, since this was a cross-sectional study we do not have longitudinal data on outcomes of individual patients. It is known that improvement in functional status continues to happen for 3-6 months after stroke and some of those interviewed earlier may still have been improving at the time of interview. Our sub-analysis however did not show any significant difference in outcomes of patients interviewed at 1-5 months and those interviewed later. Fourthly, although the outcome scales that we used have been validated for telephonic interviews, Urdu translation/cross-cultural factors may have affected results. Also, difficulty in data collection and quality rating were not evaluated. However, after pre-testing the Urdu version, the interviewer made sure that appropriate "trigger words" were used to avoid translational communication errors [55]. Direct observation and examination may have uncovered more cognitive issues and depression than reported. Surrogate responders may have introduced bias in reporting for depression outcomes.

Conclusions

To conclude, our study has provided valuable insight into what happens to stroke survivors in low and middle income countries once they leave the hospital. Even gains achieved in a dedicated stroke unit are diluted. Physicians and caregivers both need to focus on preventable post stroke complications. In addition, a public health approach to broader preventive measures to avoid catastrophic disabling strokes will also be a viable way forward.

Solutions for the current resource poor situation include care giver training for both rehabilitation and skills to recognize cognitive and psychological complications before the patient goes home. Future trials that assess the impact of caregiver education and support, home based rehabilitation and community based reintegration of Pakistani stroke survivors are likely to have broader relevance in this region.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MK, Conducted the study, developed the protocol, wrote the manuscript and secured the funding as above. BA, Conceived and performed all statistical analysis and provided epidemiologic feedback on the manuscript. MA, Participated with interviews and data collection. MN, Participated with data collection and entry processes. ER, Participated with data collection and entry processes. FK, Participated with data collection and entry processes. AM, Participated with data collection and entry processes. DS, Participated with data collection and entry processes. AA, Participated with data collection and entry processes. AKK, Conceived the idea, provided overview with study protocol, questionnaire design, analysis and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Annexure 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6.

Contributor Information

Maria Khan, Email: maria.khan@aku.edu.

Bilal Ahmed, Email: bilal.ahmed@aku.edu.

Maryam Ahmed, Email: drmaryamahmed@hotmail.com.

Myda Najeeb, Email: mydanajeeb@hotmail.com.

Emmon Raza, Email: emmonraza@yahoo.com.

Farid Khan, Email: drfaridkhan@hotmail.com.

Anoosh Moin, Email: anoosh_moin@hotmail.com.

Dania Shujaat, Email: shujaat.dania@gmail.com.

Ahmed Arshad, Email: ahmed.arshad@live.com.

Ayeesha Kamran Kamal, Email: ayeesha.kamal@aku.edu.

Acknowledgements

Grant Support for the Outcomes Project provided by the University Research Council 10GS015MED awarded to Dr Maria Khan (PI) and Dr Ayeesha Kamran Kamal (Supervisor). Dr Maria Khan is a neurovascular research fellow whose training is currently funded by Award Number D43TW008660 from the Fogarty International Center and the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Fogarty International Center, National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke or the National Institute of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Dans A, Ng N, Varghese C, Tai ES, Firestone R, Bonita R. The rise of chronic non-communicable diseases in southeast Asia: time for action. Lancet. 2011;377(9766):680–689. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal AK, Itrat A, Murtaza M, Khan M, Rasheed A, Ali A. et al. The burden of stroke and transient ischemic attack in Pakistan: a community-based prevalence study. BMC Neurol. 2009;9:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-9-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carod-Artal J, Egido JA, Gonzalez JL, Varela de Seijas E. Quality of life among stroke survivors evaluated 1 year after stroke: experience of a stroke unit. Stroke. 2000;31(12):2995–3000. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.31.12.2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton H, Feigin V, Kerse N, Barber PA, Weatherall M, Bennett D. et al. Ethnicity and functional outcome after stroke. Stroke. 2011;42(4):960–964. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.605139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottenbacher KJ, Campbell J, Kuo YF, Deutsch A, Ostir GV, Granger CV. Racial and ethnic differences in postacute rehabilitation outcomes after stroke in the United States. Stroke. 2008;39(5):1514–1519. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.501254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohra EA, Ahmed WU, Ali M. Aetiology and prognostic factors of patients admitted for stroke. J Pak Med Assoc. 2000;50(7):234–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed R, Shakir AH, Moizuddin SS, Haleem A, Ali S, Durrani K. et al. Predictors of in-hospital mortality for intracerebral hemorrhage: a hospital-based study in Pakistani adults. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2001;10(3):122–127. doi: 10.1053/jscd.2001.25462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan A, Khealani BA, Shafqat S, Aslam M, Salahuddin N, Syed NA. et al. Stroke-associated pneumonia: microbiological data and outcome. Singapore Med J. 2006;47(3):204–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan LR, Gorelick PB, Hier DB. Race, sex and occlusive cerebrovascular disease: a review. Stroke. 1986;17(4):648–655. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.17.4.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick PB, Caplan LR, Hier DB, Parker SL, Patel D. Racial differences in the distribution of anterior circulation occlusive disease. Neurology. 1984;34(1):54–59. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick PB, Caplan LR, Hier DB, Patel D, Langenberg P, Pessin MS. et al. Racial differences in the distribution of posterior circulation occlusive disease. Stroke. 1985;16(5):785–790. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.16.5.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco RL, Kargman DE, Zamanillo MC. Race-ethnic differences in stroke risk factors among hospitalized patients with cerebral infarction: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Neurology. 1995;45(4):659–663. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.4.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M, Atula S, Bath PM, Grotta J, Hacke W, Lyden P. et al. Stroke outcome in clinical trial patients deriving from different countries. Stroke. 2009;40(1):35–40. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.518035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truelsen T, Heuschmann PU, Bonita R, Arjundas G, Dalal P, Damasceno A. et al. Standard method for developing stroke registers in low-income and middle-income countries: experiences from a feasibility study of a stepwise approach to stroke surveillance (STEPS Stroke) Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(2):134–139. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70686-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xian Y, Holloway RG, Noyes K, Shah MN, Friedman B. Racial differences in mortality among patients with acute ischemic stroke: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(3):152–159. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-154-3-201102010-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhamoon MS, Tai W, Boden-Albala B, Rundek T, Paik MC, Sacco RL. et al. Risk of myocardial infarction or vascular death after first ischemic stroke: the Northern Manhattan Study. Stroke. 2007;38(6):1752–1758. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.480988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng W, Hendry RM, Adams RJ. Risk of recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, or death in hospitalized stroke patients. Neurology. 2010;74(7):588–593. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cff776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravata DM, Ho SY, Meehan TP, Brass LM, Concato J. Readmission and death after hospitalization for acute ischemic stroke: 5-year follow-up in the medicare population. Stroke. 2007;38(6):1899–1904. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.481465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshminarayan K, Schissel C, Anderson DC, Vazquez G, Jacobs DR Jr, Ezzeddine M. et al. Five-year rehospitalization outcomes in a cohort of patients with acute ischemic stroke: Medicare linkage study. Stroke. 2011;42(6):1556–1562. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.605600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saposnik G, Kapral MK, Liu Y, Hall R, O'Donnell M, Raptis S. et al. IScore: a risk score to predict death early after hospitalization for an acute ischemic stroke. Circulation. 2009;123(7):739–749. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.983353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankey GJ. Long-term outcome after ischaemic stroke/transient ischaemic attack. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;16(Suppl 1):14–19. doi: 10.1159/000069936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal PM, Malik S, Bhattacharjee M, Trivedi ND, Vairale J, Bhat P. et al. Population-based stroke survey in Mumbai, India: incidence and 28-day case fatality. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;31(4):254–261. doi: 10.1159/000165364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das SK, Banerjee TK, Biswas A, Roy T, Raut DK, Mukherjee CS. et al. A prospective community-based study of stroke in Kolkata, India. Stroke. 2007;38(3):906–910. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258111.00319.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleu D, Inshasi J, Akhtar N, Ali J, Vurgese T, Ali S. et al. Risk factors, management and outcome of subtypes of ischemic stroke: a stroke registry from the Arabian Gulf. J Neurol Sci. 2010;300(1-2):142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulart AC, Bensenor IM, Fernandes TG, Alencar AP, Fedeli LM, Lotufo PA. Early and One-Year Stroke Case Fatality in Sao Paulo. Brazil: Applying the World Health Organization's Stroke STEPS; 2011. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuschmann PU, Wiedmann S, Wellwood I, Rudd A, Di Carlo A, Bejot Y. et al. Three-month stroke outcome. Neurology. 2010;76(2):159–165. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318206ca1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr JP, Choi DW, Grotta JC, Weir B, Wolf PA. Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Paci M, Nannetti L, D'Ippolito P, Lombardi B. Outcomes from ischemic stroke subtypes classified by the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project: a systematic review. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2011. [PubMed]

- Sturm JW, Donnan GA, Dewey HM, Macdonell RA, Gilligan AK, Srikanth V. et al. Quality of life after stroke: the North East Melbourne Stroke Incidence Study (NEMESIS) Stroke. 2004;35(10):2340–2345. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000141977.18520.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turhan N, Atalay A, Muderrisoglu H. Predictors of functional outcome in first-ever ischemic stroke: a special interest to ischemic subtypes, comorbidity and age. NeuroRehabilitation. 2009;24(4):321–326. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2009-0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J, Yuen YK, Kay R, Nicholls MG. Survival, disability, and residence 20 months after acute stroke in a Chinese population: implications for community care. Disabil Rehabil. 1992;14(1):36–40. doi: 10.3109/09638289209166425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeng JS, Huang SJ, Tang SC, Yip PK. Predictors of survival and functional outcome in acute stroke patients admitted to the stroke intensive care unit. J Neurol Sci. 2008;270(1-2):60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson RG, Spalletta G. Poststroke depression: a review. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(6):341–349. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendlebury ST, Rothwell PM. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with pre-stroke and post-stroke dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(11):1006–1018. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Lin Y, Geng JL, Li HW, Chen Y, Li YS. The prevalence and risk factors for cognitive impairment following ischemic stroke. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2008;47(12):981–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naarding P, de Koning I, van Kooten F, Janzing JG, Beekman AT, Koudstaal PJ. Post-stroke dementia and depression: frontosubcortical dysfunction as missing link? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(1):1–8. doi: 10.1002/gps.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng MC, Lin HJ. Readmission after hospitalization for stroke in Taiwan: results from a national sample. J Neurol Sci. 2009;284(1-2):52–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasner SE, Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett-Smith H, Stern BJ, Hertzberg VS. et al. Predictors of ischemic stroke in the territory of a symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. Circulation. 2006;113(4):555–563. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.578229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin J. Cerebral vascular accidents in patients over the age of 60. I. General considerations. Scott Med J. 1957;2(4):127–136. doi: 10.1177/003693305700200401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonita R, Beaglehole R. Recovery of motor function after stroke. Stroke. 1988;19(12):1497–1500. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.19.12.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, Schouten HJ, van Gijn J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke. 1988;19(5):604–607. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.19.5.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn TJ, Dawson J, Walters MR, Lees KR. Reliability of the modified Rankin Scale: a systematic review. Stroke. 2009;40(10):3393–3395. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.557256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinar D, Gross CR, Bronstein KS, Licata-Gehr EE, Eden DT, Cabrera AR. et al. Reliability of the activities of daily living scale and its use in telephone interview. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1987;68(10):723–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham GE, Phillips TF, Labi ML. ADL status in stroke: relative merits of three standard indexes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1980;61(8):355–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin C, Wade DT, Davies S, Horne V. The Barthel ADL Index: a reliability study. Int Disabil Stud. 1988;10(2):61–63. doi: 10.3109/09638288809164103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, Roth M. The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects. Br J Psychiatry. 1968;114(512):797–811. doi: 10.1192/bjp.114.512.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern Y, Hesdorffer D, Sano M, Mayeux R. Measurement and prediction of functional capacity in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1990;40(1):8–14. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zillmer EA, Fowler PC, Gutnick HN, Becker E. Comparison of two cognitive bedside screening instruments in nursing home residents: a factor analytic study. J Gerontol. 1990;45(2):P69–P74. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.2.p69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madureira S, Guerreiro M, Ferro JM. Dementia and cognitive impairment 3 months after stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2001;8(6):621–627. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aben I, Verhey F, Lousberg R, Lodder J, Honig A. Validity of the beck depression inventory, hospital anxiety and depression scale, SCL-90, and hamilton depression rating scale as screening instruments for depression in stroke patients. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(5):386–393. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.5.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter P, Werner J, Heerlein A, Kraus A, Sauer H. On the validity of the Beck Depression Inventory. A review. Psychopathology. 1998;31(3):160–168. doi: 10.1159/000066239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosking SG, Marsh NV, Friedman PJ. Poststroke depression: prevalence, course, and associated factors. Neuropsychol Rev. 1996;6(3):107–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01874894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger K, Hense HW, Rothdach A, Weltermann B, Keil U. A single question about prior stroke versus a stroke questionnaire to assess stroke prevalence in populations. Neuroepidemiology. 2000;19(5):245–257. doi: 10.1159/000026262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Annexure 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6.