Abstract

Study Objectives:

Insomnia is common, persistent, and associated with relapse in alcohol-dependent (AD) patients. Although the underlying mechanisms are mostly unstudied, AD patients have impaired circadian rhythms and sleep drive, which may be genetically influenced. A polymorphism in the PER3 gene (PER34/4, PER34/5, PER35/5) has previously been associated with circadian preference and sleep homeostasis, and the PER34/4genotype has been characterized by evening preference and decreased sleep drive. The purpose of this study was to examine the influence of this polymorphism on insomnia severity in AD patients. We hypothesized that the PER3 polymorphism would be an independent predictor of insomnia severity with greatest severity observed in those with the PER34/4genotype.

Design:

Cross-sectional association of patient characteristics, genotype, and insomnia severity. Significant (P < 0.05) bivariate correlates were further analyzed by hierarchical, forced entry multiple linear regression.

Setting:

Alcohol treatment programs in Warsaw, Poland.

Patients:

Diagnosed with alcohol dependence (n = 285), according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition.

Measurements and Results:

Drinking frequency, mental and physical health status, childhood abuse, and PER3 genotype were independent predictors of insomnia severity, as measured by a 7-item subscale of the Sleep Disorders Questionnaire, explaining 28.9% of the variance. Addition of the genotype in the final step significantly increased the amount of variance explained by 1.1% (P = 0.027). Those with the PER34/4genotype had the greatest severity of insomnia symptoms.

Conclusions:

PER3 genotype contributed unique variance in predicting insomnia severity in AD patients. These results are consistent with genetically influenced impairment in sleep regulation mechanisms in AD patients with insomnia.

Citation:

Brower KJ; Wojnar M; Sliwerska E; Armitage R; Burmeister M. PER3 polymorphism and insomnia severity in alcohol dependence. SLEEP 2012;35(4):571-577.

Keywords: Sleep, alcoholism, clock gene

INTRODUCTION

PER3 is a gene that codes for a protein involved in sleep regulation. A variable number tandem repeat polymorphism, based on 4-repeat or 5-repeat alleles, results in 3 PER3 genotypes: PER34/4, PER34/5, and PER35/5. The PER35/5 genotype is associated with morning circadian preference1,2 and higher homeostatic sleep drive1,3,4 in healthy individuals. Conversely, the PER34/4 genotype is associated with evening circadian preference1,2 and lower homeostatic sleep drive.1,3,4 One manifestation of lowered homeostatic sleep drive is prolonged sleep latency (SL).3

Between 36% and 91% of alcohol-dependent (AD) patients complain of insomnia either during or after withdrawal from alcohol.5,6 Insomnia in AD patients can be persistent7,8 and associated with relapse to drinking,5 hence its clinical relevance. Correlates of insomnia in AD patients include female sex, intensive patterns of drinking consumption, severity of alcohol dependence, psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses (especially depression and anxiety), and other drug use.5,8 Polysomnographic characteristics of AD patients include prolonged SL and decreased sleep efficiency, which have been associated with self-reported insomnia in AD patients.9

Furthermore, both impaired homeostatic sleep drive10 and circadian rhythm dysfunction11 have been reported in AD individuals. Drinking shows an evening circadian preference.12 Because PER3 genetic variants have previously been found to be associated with sleep homeostasis and circadian preference, we examined the relationship between PER3 genotypes and severity of insomnia in AD patients. We hypothesized that the PER3 genotype would significantly and independently predict insomnia severity. Specifically, we hypothesized that AD patients with the PER34/4 genotype would have worse insomnia than those with the PER35/5 genotype, consistent with prior research reporting that individuals with the PER34/4 genotype have prolonged SL and decreased homeostatic sleep drive.

METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were recruited from 4 addiction treatment facilities in Warsaw, Poland, if they were at least 18 yr old and met criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition13 for alcohol dependence. Exclusion criteria included a current diagnosis of psychosis or mania, being an imminent danger to self or others, or cognitive impairment as indicated by a score < 25 on the Mini-Mental State Examination.14 Of 304 patients who consented to participate, 291 had usable genotype data for the PER3 variable number tandem repeat polymorphism. The distribution of genotypes was 88 (30.2%) for PER34/4, 156 (53.6%) for PER34/5, and 47 (16.2%) for PER35/5, which corresponds to allele frequencies of 0.57 for the 4-repeat allele and 0.43 for the 5-repeat allele. This distribution of alleles and genotypes is similar to published frequencies for European Caucasians or European Americans (i.e., American Caucasians of European descent)4,15 and is in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P = 0.109). Of the 291 patients with PER3 data, 285 had complete data for the primary measure of insomnia severity and constitute the sample for this study.

Demographically, all study participants were European Caucasians, 25.3% were female, 51.6% were married, and 39.6% were employed. They had a mean (standard deviation, SD) age of 43.2 (9.6) yr. In terms of other substance use, 79.3% smoked tobacco and 14.0% took other drugs (cannabis, cocaine, other stimulants, opioids, sedatives-hypnotics, hallucinogens, inhalants, or phencyclidine) in the 28 days prior to baseline assessment.

This study was approved by both the Bioethics Committee at the Medical University of Warsaw and the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. All participants signed written informed consent prior to completing any study assessments.

Measures

Sleep Disorders Questionnaire (SDQ7)

These 7 items were derived specifically for this study from the 175-item self-administered Sleep Disorders Questionnaire.16 This questionnaire was chosen for its 6-mo time frame. In contrast to other commonly used insomnia measures, such as the Insomnia Severity Index with its past 1-wk time frame17 and the Athens Insomnia Scale with its past 1-mo time frame,18 the 6-mo duration of the SDQ7 is more likely to identify chronic insomnia, which in turn is less likely to be influenced by acute stressors or precipitants. Accordingly, it may better reflect a genetic predisposition to trouble sleeping. The 7 items presented in Table 1 were selected for their face validity with insomnia. Each item is rated on a scale of 0-4, with 0 indicating either “Never” or “Strongly Disagree” and 4 indicating either “Always” or “Agree Strongly”. The means, SDs, and percentage of patients endorsing each item at a level of 3 (“Usually” or “Agree”) or 4 are also presented in Table 1. No notable deviation from normality was evident in the frequency distribution of SDQ7 total scores, based on visual inspection of the histogram and Q-Q plot, and values for skewness (0.308) and kurtosis (-0.790). The Cronbach α for the scale was 0.94 in this sample and a factor analysis extracted 1 component with an Eigenvalue of 5.19 that explained 74.1% of the variance.

Table 1.

SDQ7 items and descriptive statistics (n = 285)

| SDQ7 Item | Mean (SD) | Item Endorseda |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| I get too little sleep at night | 2.0 (1.1) | 98 | 34.4% |

| I often have a poor night's sleep | 1.8 (1.2) | 83 | 29.1% |

| I have trouble getting to sleep at night | 1.9 (1.2) | 101 | 35.4% |

| I wake up often during the night | 1.9 (1.2) | 98 | 34.4% |

| I feel that my sleep is abnormal | 1.7 (1.3) | 85 | 29.8% |

| I feel that I have insomnia | 1.2 (1.2) | 46 | 16.1% |

| I have a problem with my sleep | 1.7 (1.3) | 81 | 28.4% |

| Total score | 12.3 (7.3) | 150 | 52.6%b |

n (%) who rated items as either a 3 or 4 on a 0-4 (5-point) scale.

n (%) who rated at least 1 of the items as either a 3 or 4. SDQ7, 7-item Sleep Disorders Questionnaire Insomnia Subscale.

In a previous study,9 we used a scale in AD patients called the SDQ8, which included all items from the SDQ7 plus the following additional item: “I have been unable to sleep at all for several days”. Because this eighth item was endorsed by only 3.5% of patients in that study, it was dropped prior to this more recent study. The previous study did show that the SDQ8 had predictive validity in identifying patients who subsequently relapsed to drinking.9 Additional unpublished analyses from that study demonstrated that the SDQ7 also predicted relapse to drinking.

The Revised NEO Personality Inventory

The Revised NEO Personality Inventory,19,20 assesses personality traits, which are enduring patterns of experiencing and responding to life situations that are influenced by genetic variation. These traits generally begin in adolescence and early adulthood and are stable over time.13 Early work in this area suggested that patients with insomnia were characterized more by internalizing traits such as depressive tendencies than externalizing traits such as acting out or aggression.21 For this study, the personality dimensions of neuroticism and impulsivity were selected, because recent work suggests that both neuroticism22 and impulsivity23,24 are associated with insomnia. Furthermore, impulsivity may be related to eveningness.25 Neuroticism, an internalizing trait, has been defined as “an enduring tendency to experience negative emotional states.”22 Impulsiveness, an externalizing trait, is common among AD patients.26 The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale27 is a 30-item, self-administered questionnaire that was used as a second measure of impulsivity and ranges from 30 to 120, with higher scores indicating greater impulsiveness.

Short Form-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales

The Short Form-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales28 were used to measure physical and mental components of health status, and are indicators of physical and mental health severity with a past 1-mo time frame, respectively. They were selected because both physical and psychiatric disorders are frequently associated with insomnia symptoms, and co-occurring disorders are common in AD patients. Expressed as standardized T scores relative to the general population, which has a mean of 50 and SD of 10, scores above and below the mean indicate better and worse health than the average person, respectively.

Childhood abuse history

By a self-administered questionnaire, all patients were asked 2 yes-no questions regarding physical and sexual abuse prior to age 18 yr: “Were you ever hit, beaten, or physically abused so much that you feared for your safety or had marks?” and “Did anyone ever have any kind of sexual contact with you against your wishes?” Patients who answered yes to either or both questions were classified with a history of childhood abuse. Childhood abuse and trauma are strong predictors of mental and physical disorders in later life29,30 and interact with genetic factors in the development of alcohol dependence.31 Other studies have found correlations between childhood abuse and adult insomnia after adjusting for psychiatric symptoms.32,33 Whether the potential effects of childhood abuse on adult insomnia in AD patients operate independently of mental and physical health problem severity is unknown.

Alcohol dependence

A number of measures were used to characterize patients on the basis of their drinking. The Polish version34,35 of the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test36 is a 24-item, self-administered questionnaire that was used to measure severity of alcohol dependence as a disorder. Scores range from 0 to 53, with higher scores indicating greater severity. Other work has indicated that severity of dependence is associated with insomnia in AD patients.9 Age at onset of problem drinking is another measure that correlates with severity of dependence. In general, individuals with earlier onset have greater severity of dependence. The Short Index of Problems (also known as the Short Inventory of Problems) is a 15-item, self-administered measure of drinking-related problems during the past 4 wk with a scoring range from 0 to 45, with higher scores indicating greater problems.37 It is included because worry about adverse consequences from drinking such as job-related and legal problems might precipitate or perpetuate insomnia in AD patients. The number of self-reported drinking days and total number of standard drinks in the past 90 days at baseline are quantity and frequency measures of drinking to indicate whether alcohol consumption might be contributing to insomnia as shown in previous studies.38,39

Genetic Analysis

DNA was extracted from fresh whole blood using Puregene Kits (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and mailed to the United States in batches. PER3 was genotyped by polymerase chain reaction followed by length determination by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gel at 8 V/cm for 1 hr, visualized by ethidium bromide staining.40

Data Analysis

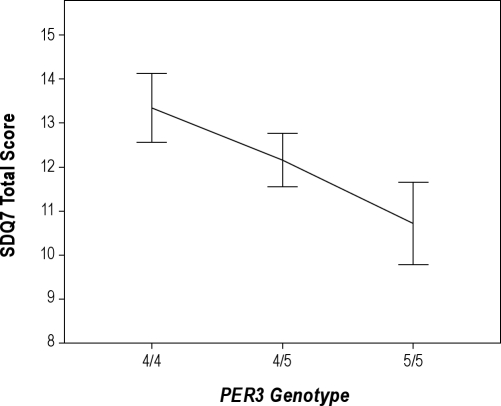

To examine the relationship between the PER3 polymorphism and insomnia severity, the mean SDQ7 insomnia scores were graphed as a function of the PER34/4, PER34/5, and PER35/5 genotypes. Figure 1 illustrates an additive effect of genetic variation on insomnia severity, illustrated by the intermediate value of the mean insomnia score for those with the heterozygous (PER34/5) genotype as compared to the mean scores for the 2 homozygous genotypes. To evaluate the linear relationship between PER3 genotype and insomnia severity as depicted in Figure 1, a simple regression analysis was run after coding the PER3 genotype as an interval variable with PER34/4= 1, PER34/5 = 2, and PER35/5 = 3. Most geneticists prefer linear regression as the first test of genetic association to determine the amount of variance in a quantitative trait explained by a genetic polymorphism.41 This is because it makes the least number of assumptions. It assumes an additive effect without dominance or hyperdominance between alleles. Nevertheless, we also performed 2 secondary analyses of the bivariate relationship between genotype and insomnia severity. The first was a 1-way analysis of variance, which compared all 3 genotypes without any assumption of an additive relationship. Second, we ran an independent samples t test to evaluate the hypothesis that PER34/4individuals would have greater insomnia severity than PER35/5 individuals, as these 2 genotypes have been compared in sleep laboratory studies.3,42

Figure 1.

Mean (± 1 standard error) SDQ7 total scores (n = 285) for each PER3 genotype illustrating an additive genetic model. Sample sizes by genotype are n = 87 for PER34/4, n = 152 for PER34/5, and n = 46 for PER35/5. SDQ7, 7-item insomnia subscale of the Sleep Disorders Questionnaire.

For other potential predictors of insomnia severity, we selected variables that have been associated in the literature with insomnia in either the general population or specifically in AD patients as described previously. Continuous variables were checked for normality using visual inspection of histograms and Q-Q plots, and values of < 1 for skewness and kurtosis. Descriptive results for continuous variables are expressed as means and SDs for normally distributed variables, and as medians and interquartile ranges for nonnormal distributions. Similarly, correlations between normally distributed variables and SDQ7 scores were analyzed with Pearson correlation tests, whereas variables with nonnormal distributions were analyzed with Spearman rho correlation tests. Independent sample t tests compared SDQ7 score means as a function of dichotomized variables such as sex. All tests were 2-tailed, using a P value of < 0.05 for significance in bivariate analyses.

Significant predictors from bivariate analyses were selected for regression modeling. A hierarchical regression model was developed to determine how much additional variance was explained by genotype after accounting for all other significant predictors of insomnia severity.43 Thus, PER3 genotype was entered in the second block after all other potential predictors were entered in the first block. All variables were forced to stay in the model. Analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics version 17.0 (PASW, Inc., San Ramon, CA).

RESULTS

The results of a simple regression analysis revealed that the PER3 genotype was a significant predictor of insomnia severity (F = 4.03 (1,283), P = 0.046, adjusted R2 = 0.011), and it confirmed a linear relationship between them (Figure 1). By contrast, an analysis of variance comparing all 3 genotypes was not significant (F = 2.02 (2,282), P = 0.135). Finally, the difference in insomnia scores between PER34/4and PER35/5 individuals (13.3 [7.3] and 10.7 [6.3], respectively) was significant (t = 2.07, df = 131, P = 0.040).

Other characteristics of the sample and their bivariate associations with SDQ7 insomnia scores are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Differences in mean SDQ scores by dichotomous variables are shown in Table 2, indicating that childhood abuse was associated with insomnia severity, whereas sex, marital status, employment, drug use, and smoking were not. Correlations between continuous variables and SDQ7 scores revealed that education, neuroticism, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-measured impulsivity, Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST) score, alcohol-related consequences (Short Index of Problems (SIP) score), drinking days and total number of drinks in the past 3 mo, and mental and physical health severity were significantly associated with insomnia (Table 3). Age, NEO impulsivity scores, and age at onset of problem drinking, however, were not.

Table 2.

Mean SDQ7 scores by patient characteristics

| na (%) | Mean (SD) | t | P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 72 (25.3) | 11.9 (7.0) | -0.48 | 0.632 |

| Male | 213 (74.7) | 12.4 (7.4) | ||

| Childhood abuse | ||||

| No | 176 (66.9) | 11.3 (7.0) | ||

| Yes | 87 (33.1) | 14.3 (7.4) | -3.30 | 0.001 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Not married | 138 (48.4) | 13.1 (7.3) | ||

| Married | 147 (51.6) | 11.5 (7.3) | 1.78 | 0.076 |

| Employment | ||||

| No | 171 (60.2) | 12.6 (7.4) | ||

| Yes | 113 (39.8) | 11.7 (7.2) | 1.09 | 0.275 |

| Drug use (past 28 days) | ||||

| No | 245 (86.0) | 12.2 (7.4) | ||

| Yes | 40 (14.0) | 12.6 (6.9) | -0.32 | 0.753 |

| Smoking | ||||

| No | 59 (20.7) | 13.4 (7.9) | ||

| Yes | 226 (79.3) | 12.0 (7.3) | 1.33 | 0.186 |

Sample sizes for some variables are less than 285 due to missing data.

Significant values bolded. SD, standard deviation; SDQ7, 7-item Sleep Disorders Questionnaire Insomnia Subscale.

Table 3.

Correlations between SDQ7 and patient characteristics

| na | Averageb | Correlationc | P valued | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (yr) | 285 | 43.2 (9.6) | 0.081 | 0.170 |

| Education (yr) | 231 | 12.1 (2.6) | -0.202 | 0.002 |

| Personality variables | ||||

| NEO neuroticism | 284 | 62.1 (10.3) | 0.351 | < 0.0005 |

| NEO impulsivity | 284 | 52.7 (9.1) | 0.058 | 0.327 |

| BIS impulsiveness | 284 | 71.4 (9.8) | 0.249 | < 0.0005 |

| Alcohol variables | ||||

| Age at onset (yr) | 280 | 21.0 (18.0-28.0) | -0.072 | 0.228 |

| MAST score | 285 | 35.0 (29.0-41.0) | 0.135 | 0.023 |

| SIP score | 266 | 24.0 (11.1) | 0.267 | < 0.0005 |

| Drinking days (past 3 mo) | 273 | 27.0 (3.5-52.5) | 0.134 | 0.027 |

| Standard drinks (past 3 mo) | 224 | 567.0 (268.8-957.4) | 0.158 | 0.018 |

| SF36 composite health variables | ||||

| Mental health | 282 | 38.5 (12.1) | -0.422 | < 0.0005 |

| Physical health | 282 | 48.7 (40.8 -54.2) | -0.349 | < 0.0005 |

Sample sizes for some variables are less than 285 due to missing data.

Mean (standard deviation) and median (interquartile range) for normal and nonnormal distributions, respectively.

Pearson r and Spearman rho correlations for normal and nonnormal distributions, respectively.

Significant differences bolded. BIS, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; MAST, Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test; SF36, 36-Item Short Form of the Medical Outcomes Study; SIP, Short Index of Problems (Alcohol-Related); SDQ7, 7-item Sleep Disorders Questionnaire Insomnia Subscale.

Among the variables that were significantly associated with SDQ7 scores, the number (frequency) of drinking days in the past 3 mo was strongly correlated with the number (quantity) of standard drinks in the past 3 mo (rs = 0.83, P < 0.0005). Of these 2 variables, drinking quantity was excluded from the regression analyses to protect against collinearity and because 61 patients had missing data for this variable. None of the other variables introduced problems with collinearity. Education and total SIP scores, however, had missing data for 54 and 19 subjects, respectively, which constricted the sample size in preliminary analyses. Because neither variable was significant in a preliminary regression analysis and the significance of results for PER3 did not change with or without them, they were dropped from the models presented in the following paragraphs.

Results of the hierarchical linear regression analysis (n = 249) are shown in Table 4. Model 1, which explained 27.8% of the adjusted variance, revealed that childhood abuse, drinking frequency, mental health, and physical health were significant predictors of insomnia severity. The addition of PER3 genotype in Model 2 was found to be a significant predictor (P = 0.027) and also increased the adjusted variance by 1.1 percentage points, which represented a significant change in the model (P = 0.027).

Table 4.

Hierarchical regression models predicting insomnia severity

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Betaa | t | P valueb | Betaa | t | P valueb | |

| Childhood abuse | 0.143 | 2.50 | 0.013 | 0.154 | 2.70 | 0.008 |

| NEO neuroticism | 0.109 | 1.44 | 0.151 | 0.115 | 1.54 | 0.125 |

| BIS | −0.040 | −0.58 | 0.565 | −0.059 | −0.85 | 0.396 |

| MAST score | 0.053 | 0.93 | 0.355 | 0.054 | 0.94 | 0.347 |

| Drinking days (past 3 mo) | 0.135 | 2.43 | 0.016 | 0.128 | 2.32 | 0.021 |

| SF36 Mental Health | −0.295 | −4.31 | < 0.0005 | −0.293 | −4.32 | < 0.0005 |

| SF36 Physical Health | −0.288 | −5.16 | < 0.0005 | −0.288 | −5.21 | < 0.0005 |

| PER3 | – | – | – | −0.121 | −2.23 | 0.027 |

| Adjusted R2 = 0.278 | Adjusted R2 = 0.289 | |||||

| F = 14.61 (7,241), P < 0.0005 | ΔF = 4.96 (1,240), P = 0.027 | |||||

Standardized beta.

Significant values bolded.

BIS, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; MAST, Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test; SF36, 36-Item Short Form of the Medical Outcomes Study.

DISCUSSION

The major finding in this study was that genetic variation in PER3 was associated with severity of insomnia in a sample of AD patients. Consistent with our directional hypothesis, AD patients who were homozygous for the 4-repeat allele (PER34/4) had significantly worse insomnia scores than those homozygous for the 5-repeat allele (PER35/5). This hypothesis was based on, and consistent with, previous comparisons of homozygous PER3 genotypes in the literature, which indicate that the PER34/4genotype correlates with prolonged SL and lowered homeostatic sleep drive.1,3 However, this study did not measure SL or homeostatic sleep drive.

The results also show that AD patients with the heterozygous genotype (PER34/5) had insomnia severity scores that were intermediate between those of the homozygotes, indicative of an additive genetic model. Furthermore, the analysis of all 3 genotypes revealed that the PER3 polymorphism predicted severity of insomnia in AD patients after controlling for other known predictors, and added significantly to the unique variance explained by the regression model. That change in variance, on the order of 1%, is consistent with the usual contribution of genetic factors to complex phenotypes, for which insomnia would qualify.

The final overall model explained 28.9% of the adjusted variance and included childhood abuse, drinking frequency, and both mental and physical health problem severity in addition to PER3 genotype. The finding that mental and physical health problems are associated with insomnia severity was expected from studies of the general population,44,45 and psychiatric severity also has been correlated with insomnia in samples of AD patients.8,38,46 Studies have also reported that measures of alcohol consumption correlate with insomnia in AD patients.38,39

The relationship between childhood abuse and negative health outcomes in adults is well established.29,30,47 Although insomnia is also associated with negative health outcomes, this study suggests that childhood abuse independently predicts severity of insomnia while controlling for both physical and mental health problems. This is consistent with previous findings in women for whom childhood sexual abuse predicted later sleep disturbances independently of depression and posttraumatic disorder32 and for women, sexually abused in childhood, whose insomnia persisted despite response of their depression to psychotherapy.33 This study extends those findings to a sample of mostly male AD patients.

Limitations

First, the SDQ7 is a novel insomnia subscale of the Sleep Disorders Questionnaire.16 Preliminary analyses from this study indicate that some of its psychometric properties are strong. It is characterized by high internal consistency, items that load onto 1 factor, a normal distribution, and strong expected correlations with mental and physical health scales. Nevertheless, further validation of the SDQ7 is warranted, because it has not yet been validated against a gold-standard diagnostic measure of insomnia or a well-established scale such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index,48 nor has it been tested for repeat reliability. In addition, its content does not include measures of daytime impairment. Although statistically significant, the clinical significance of the mean difference between PER34/4and PER35/5individuals of 2.6 points on this scale is unclear. Its primary advantage in comparison to other established sleep scales, however, is its 6-mo time frame, which is arguably more likely to reflect an enduring genetically influenced sleep trait than scales with time frames of the past 1 to 4 wk. Conversely, these shorter-term scales may more likely reflect the sleep response to acutely stressful events that are associated with treatment-seeking in a sample of AD patients.

Second, the clinical significance of genotyping individuals who have complex disorders or traits has not generally been demonstrated, and there is no immediate clinical application of our results. Phenotypes such as insomnia severity are complex, because a single genetic variant at best only explains a small fraction of the overall variation. In this case, however, 1.1% of the variance was both statistically significant and consistent with what is generally found in genetic studies of complex disorders.

Third, the finding of increased insomnia severity among carriers of the PER34/4 genotype is consistent with studies reporting that this genotype is associated with evening circadian preference, lower homeostatic sleep drive, and prolonged SL in healthy volunteers. Although the rationale for this study was based on these physiologic data in healthy volunteers from the literature, no such data were collected in this study sample of AD patients. As neither objective sleep parameters nor circadian preference (i.e., morningness-eveningness49) was measured in this study, it was not possible to compute correlations of genotoype with polysomnography and circadian rhythm parameters. Fourth, the sample size for the regression analysis was reduced from 285 to 249, due to missing data. Genetic studies with small sample sizes can be difficult to replicate. Furthermore, it can be argued that the P values for simple regression across all 3 genotypes (P = 0.046) and the t test between homozygous genotypes (P = 0.040) would not survive correction for multiple testing. Thus, study findings have to be seen as preliminary and will require independent replication in larger groups of AD patients.

Fifth, although the analysis controlled for mental and physical health problem severity, specific diagnoses of co-occurring psychiatric and medical disorders were not assessed consistently for research purposes to be included in the analyses. However, psychiatric diagnoses as determined by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview50 were available in a subsample of 140 patients, of whom 25% had a current mood disorder (major depression, dysthymic disorder, or hypomania) and 11.4% had a current anxiety disorder (generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder). A total of 30.7% had either a mood or anxiety disorder. Those with mood and/or anxiety disorders did not differ in their SDQ7 scores from those without a comorbid disorder (P = 0.47), whereas they did have significantly worse mental health scores (P < 0.0005). Thus, it would appear that mental health severity was a better predictor of insomnia severity than psychiatric diagnosis in this sample. Similarly, 14% of patients reported use of other drugs in the 28 days prior to study, indicating that some patients may have had co-occurring drug use disorders. Insomnia severity scores did not differ, however, between those with and without drug use (Table 2). Moreover, entering drug use as a covariate in the regression models did not change the overall findings (results not shown). Despite these observations, the major findings reported here may not extend to particular subgroups of AD patients with specific comorbid conditions. Future research should investigate sleep regulation mechanisms and genetic variation in larger samples and subgroups of AD patients.

Finally, insomnia in AD patients has been associated with relapse to drinking in other studies, but this relationship is not addressed here. Whether PER3 variation influences relapse or the relationship between insomnia and relapse in AD patients is unknown, but deserving of further study.

In conclusion, PER34/4 genotype, previously associated with evening circadian preference and decreased homeostatic sleep drive, contributed unique variance in predicting insomnia severity in AD patients. These results are consistent with genetically influenced impairment in sleep regulatory mechanisms in AD patients with insomnia symptoms. The clinical implications of these findings remain to be determined, but the reported relationship between sleep disturbances and relapse to drinking in AD patients5 suggests that correcting underlying mechanisms, especially in genetically susceptible patients, may improve treatment outcomes.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Armitage is a consultant for Eisai Inc. and has received equipment from Braebon Medical Corporation. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Mrs. Gang Su for help with genotyping and all members of the research team in Poland (especially, Andrzej Jakubczyk, MD; Katarzyna Kositorna, MS; Maciej Kopera, MD; Aleksandra Konopa, MD; Julia Pupek, MD; Izabela Nowosad, MD) as well as the medical staff and patients at “Kolska,” “Pruszkow,” “Petra” and “Solec” Addiction Treatment Centers in Warsaw for their support of this research. Work performed at the University of Michigan and the Medical University of Warsaw. Supported by Grants R21AA016104-02, 2K24AA00304-10, Fogarty International Center/NIDA D43-TW05818, and the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education Grant 2P05D00429.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dijk DJ, Archer SN. PERIOD3, circadian phenotypes, and sleep homeostasis. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:151–60. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archer SN, Robilliard DL, Skene DJ, et al. A length polymorphism in the circadian clock gene Per3 is linked to delayed sleep phase syndrome and extreme diurnal preference. Sleep. 2003;26:413–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viola AU, Archer SN, James LM, et al. PER3 polymorphism predicts sleep structure and waking performance. Curr Biol. 2007;17:613–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goel N, Banks S, Mignot E, Dinges DF. PER3 polymorphism predicts cumulative sleep homeostatic but not neurobehavioral changes to chronic partial sleep deprivation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brower KJ. Insomnia, alcoholism and relapse. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7:523–39. doi: 10.1016/s1087-0792(03)90005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohn TJ, Foster JH, Peters TJ. Sequential studies of sleep disturbance and quality of life in abstaining alcoholics. Addict Biol. 2003;8:455–62. doi: 10.1080/13556210310001646439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drummond SP, Gillin JC, Smith TL, DeModena A. The sleep of abstinent pure primary alcoholic patients: natural course and relationship to relapse. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1796–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brower KJ, Krentzman A, Robinson EAR. Persistent insomnia, abstinence, and moderate drinking in alcohol-dependent individuals. Am J Addictions. 2011;20:435–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brower KJ, Aldrich M, Robinson EAR, Zucker RA, Greden JF. Insomnia, self-medication, and relapse to alcoholism. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:399–404. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irwin M, Gillin JC, Dang J, Weissman J, Phillips E, Ehlers CL. Sleep deprivation as a probe of homeostatic sleep regulation in primary alcoholics. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:632–41. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhlwein E, Hauger RL, Irwin MR. Abnormal nocturnal melatonin secretion and disordered sleep in abstinent alcoholics. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:1437–43. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danel T, Jeanson R, Touitou Y. Temporal pattern in consumption of the first drink of the day in alcohol-dependent persons. Chronobiology International. 2003;20:1093–1102. doi: 10.1081/cbi-120025533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nadkarni NA, Weale ME, von Schantz M, Thomas MG. Evolution of a length polymorphism in the human PER3 gene, a component of the circadian system. J Biol Rhythms. 2005;20:490–9. doi: 10.1177/0748730405281332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Douglass AB, Bornstein R, Nino-Murcia G, et al. The Sleep Disorders Questionnaire. I: Creation and multivariate structure of SDQ. Sleep. 1994;17:160–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bastien CH, Vallieres, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Medicine. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Paparrigopoulos TJ. Athens Insomnia Scale: validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48:555–60. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Domains and facets: hierarchical personality assessment using the revised NEO personality inventory. J Pers Assess. 1995;64:21–50. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6401_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costa PT, McCrae RR. Professional manual: revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI) Odessa FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kales A, Caldwell AB, Preston TA, Healey S, Kales JD. Personality patterns in insomnia. Theoretical implications. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:1128–34. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770090118013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van de Laar M, Verbeek I, Pevernagie D, Aldenkamp A, Overeem S. The role of personality traits in insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:61–8. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt RE, Gay P, Ghisletta P, Van der Linden M. Linking impulsivity to dysfunctional thought control and insomnia: a structural equation model. J Sleep Res. 2010;19:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt RE, Gay P, Van der Linden M. Facets of impulsivity are differentially linked to insomnia: evidence from an exploratory study. Behav Sleep Med. 2008;6:178–92. doi: 10.1080/15402000802162570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caci H, Robert P, Boyer P. Novelty seekers and impulsive subjects are low in morningness. Eur Psychiatry. 2004;19:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubio G, Jimenez M, Rodriguez-Jimenez R, et al. The role of behavioral impulsivity in the development of alcohol dependence: a 4-year follow-up study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1681–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51:768–74. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: a user's manual. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sachs-Ericsson N, Blazer D, Plant EA, Arnow B. Childhood sexual and physical abuse and the 1-year prevalence of medical problems in the National Comorbidity Survey. Health Psychol. 2005;24:32–40. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Springer KW, Sheridan J, Kuo D, Carnes M. Long-term physical and mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse: results from a large population-based sample of men and women. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31:517–30. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Enoch MA, Hodgkinson CA, Yuan Q, Shen PH, Goldman D, Roy A. The influence of GABRA2, childhood trauma, and their interaction on alcohol, heroin, and cocaine dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noll JG, Trickett PK, Susman EJ, Putnam FW. Sleep disturbances and childhood sexual abuse. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31:469–80. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pigeon WR, May PE, Perlis ML, Ward EA, Lu N, Talbot NL. The effect of interpersonal psychotherapy for depression on insomnia symptoms in a cohort of women with sexual abuse histories. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22:634–8. doi: 10.1002/jts.20456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falicki Z, Karczewski J, Wandzel L, Chrzanowski W. [Usefulness of the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) in Poland] Psychiatr Pol. 1986;20:38–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Habrat B. [Questionnaire methods in the diagnosis and evaluation of alcohol dependence] Psychiatr Pol. 1988;22:149–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Selzer ML. The Michigan alcoholism screening test: the quest for a new diagnostic instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;127:1653–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.127.12.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feinn R, Tennen H, Kranzler HR. Psychometric properties of the short index of problems as a measure of recent alcohol-related problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1436–41. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000087582.44674.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baekeland F, Lundwall L, Shanahan TJ, Kissin B. Clinical correlates of reported sleep disturbance in alcoholics. Q J Stud Alcohol. 1974;35:1230–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shinba T, Murashima Y, Yamamoto K-I. Alcohol consumption and insomnia in a sample of Japanese alcoholics. Addiction. 1994;89:587–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ebisawa T, Uchiyama M, Kajimura N, et al. Association of structural polymorphisms in the human period3 gene with delayed sleep phase syndrome. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:342–6. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sole X, Guino E, Valls J, Iniesta R, Moreno V. SNPStats: a web tool for the analysis of association studies. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1928–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vandewalle G, Archer SN, Wuillaume C, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging-assessed brain responses during an executive task depend on interaction of sleep homeostasis, circadian phase, and PER3 genotype. J Neurosci. 2009;29:7948–56. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0229-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 4th ed. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sivertsen B, Krokstad S, Overland S, Mykletun A. The epidemiology of insomnia: associations with physical and mental health. The HUNT-2 study. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:109–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wallander MA, Johansson S, Ruigomez A, Garcia Rodriguez LA, Jones R. Morbidity associated with sleep disorders in primary care: a longitudinal cohort study. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9:338–45. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v09n0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Foster JH, Peters TJ. Impaired sleep in alcohol misusers and dependent alcoholics and the impact upon outcome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:1044–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Talbot NL, Chapman B, Conwell Y, et al. Childhood sexual abuse is associated with physical illness burden and functioning in psychiatric patients 50 years of age and older. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:417–22. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318199d31b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roenneberg T, Kuehnle T, Juda M, et al. Epidemiology of the human circadian clock. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:429–38. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. quiz 4-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]