Abstract

Inflammation plays important roles in initiation and progress of many diseases including cancers in multiple organ sites. Herein, we investigated the anti-inflammatory effects of two dietary compounds, nobiletin (NBN) and sulforaphane (SFN) in combination. Non-cytotoxic concentrations of NBN, SFN, and their combinations were studied in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. The results showed that combined NBN and SFN treatments produced much stronger inhibitory effects on the production of nitric oxide (NO) than NBN or SFN alone at higher concentrations. These enhanced inhibitory effects were synergistic based on the isobologram analysis. Western blot analysis showed that combined NBN and SFN treatments synergistically decreased iNOS and COX-2 protein expression levels and induced heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) protein expression. Real-time PCR analysis indicated that low doses of NBN and SFN in combination significantly suppressed LPS-induced upregulation of IL-1 mRNA levels, and synergistically increased HO-1 mRNA levels. Overall our results demonstrated that NBN and SFN in combination produced synergistic effects in inhibiting LPS-induced inflammation in RAW 264.7 cells.

Keywords: Nobiletin, sulforaphane, inflammation, nitric oxide, iNOS, COX-2

INTRODUCTION

It is well recognized that inflammation plays important roles in initiation and progress of many diseases including cancers in multiple organ sites. Inflammation can be oncogenic by various mechanisms including induction of genomic instability, promoting angiogenesis, altering the genomic epigenetic status and enhancing cell proliferation [1]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) can induce iNOS expression, which in turn can increase the production of nitric oxide (NO) [2]. Studies indicated that iNOS expression was associated with several malignant tumors in human such as brain, breast, colorectal, lung, prostate, pancreatic carcinoma, and melanoma [1]. iNOS-mediated prolonged overproduction of NO has been implicated in epithelia carcinogenesis [3], and excessive NO can cause mutagenesis, damage DNA structure, and promote the formation of N-nitrosoamines [4–6]. Similar to iNOS, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) is also an inducible pro-inflammatory enzyme. COX-2 can convert arachidonic acid to prostaglandin and other eicosanoids. Aberrant functioning of COX-2 has been associated with carcinogenesis by promoting cell survival, angiogenesis, and metastasis [7–9]. Therefore, iNOS and COX-2 are important targets for anti-inflammation remedy.

Controlling inflammation has been recognized as one of important strategies for the prevention and treatment of cancer [10]. Many dietary bioactive compounds have been identified as potential anti-inflammatory agents. Nobiletin (NBN) is a polymethoxyflavone mainly found in the citrus fruits, especially in the peels. It has been shown that NBN had anti-inflammatory [11] and anti-carcinogenic activities [12]. NBN inhibited IL-1-induced production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in human synovial cells, and interfered with the LPS-induced production of PGE2 and gene expression of IL-1, TNF-α and IL-6 in mouse J774A.1 macrophages [11]. NBN also suppressed the expression of COX-2, NF-κB-dependent transcription, and PGE2 production induced by IL-1 in osteoblasts [13]. In mice, NBN was found to inhibit two distinct stages of skin inflammation induced by TPA application, and moreover, NBN was able to inhibited dimethylbenz [α] anthracene/TPA-induced skin tumor formation [14]. Sulforaphane (SFN), an aliphatic isothiocyanate found in cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli and cabbage, is a known cancer chemopreventive agent, which is in part related to its potential anti-inflammatory activities [15]. SFN has been shown to down-regulate LPS-induced iNOS, COX-2 and TNF-α expression in mouse macrophages [16], and it has been suggested that SFN exerted its anti-inflammatory activity via activation of Nrf2 in mouse peritoneal macrophages [15].

Inflammation is a complex and multi-factorial process. The use of single agents to inhibit inflammation may not achieve satisfactory outcome, and high-dose administration of certain anti-inflammatory agents alone may cause unacceptable toxicity. A growing body of evidence suggests that the combination of agents with different molecular targets may produce synergistic interactions and result in enhanced biological effects [17]. The possible favorable outcomes of synergistic interaction among different anti-inflammatory agents include increased efficacy of anti-inflammation, decreased dosage of each anti-inflammatory agents required to manifest efficacy, and minimized potential toxicity and/or side-effects from high-dose administration. In this study, for the first time we investigated the combination of NBN and SFN in terms of their potential synergy in inhibiting pro-inflammatory responses in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophage cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

RAW 264.7 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA), and were cultured in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10 % heat-inactivated FBS (Medistech, Herndon, VA, USA), 100 units/mL of penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL of streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 37 °C with 5 % CO2 and 95 % air. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was used as the vehicle to deliver NBN (> 98 %, Qualityphytochemicals Inc., Edison, NJ, USA) and SFN (> 98 %, Qualityphytochemicals Inc., Edison, NJ, USA) to the culture media, and the final concentration of DMSO in all experiments was 0.1 % v/v in cell culture media.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was determined as previously described [18]. RAW 264.7 cells (50,000 cells/well) were seeded in 96-well plates. After 24 h, cells were treated with serial concentrations of test compounds in 200 μL of serum complete media. After 24 h treatments, cells were subject to 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Media were replaced by 100 μL fresh media containing 0.1 mg/mL of MTT (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After 2 h incubation at 37 ° with 5 % CO2 and 95 % air, MTT-containing media were removed and the reduced formazan dye was solubilized by adding 100 μL of DMSO to each well. After gentle mixing, the absorbance was monitored at 570 nm using a plate reader (Elx800TM absorbance microplate reader, BioTek Instrument, Winooski, VT, USA).

Nitric oxide assay

The nitrite concentration in the culture media was measured as an indicator of NO production by the Griess reaction. The culture media were mixed with an equal volume of Griess reagent A and B (A: 1 % sulfanilamide in 5 % phosphoric acid, and B: 0.1 % naphthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride in water). Absorbance of the mixture at 540 nm was measured by a plate reader, and concentrations of nitrite were calculated according to a standard curve constructed with sodium nitrite as a standard.

Analyses of synergy

The analyses were based on isobologram method as described previously [19]. It was assumed that the dose response model follows log [E/ (1 − E)] = α(log d − log Dm), which is a linear regression model with the response log [E/ (1 − E)] and the regressor log (d). This model is used for compound 1, compound 2 and the combinations of the 2 compounds with fixed ratio of the doses of the 2 compounds. E is fraction of NO production, d is the dose applied, Dm is the median effective dose of a compound, and a is α slope parameter. On the basis of this regression model, median effect plots were constructed using data from NO assay. Suppose that the combination (d1, d2) elicits the same effect x as compound 1 alone at dose level Dx,1, and compound 2 alone at dose Dx,2, then the interaction index = d1/Dx,1 + d2/Dx,2 (Dx,1 and Dx,2 were calculated from median effect models). The interaction index was used to determine additivity, synergy, or antagonism of the combination at dose (d1, d2) depending on interaction index = 1, <1 or >1, respectively. The delta method (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delta_method) was used to calculate the variance of the interaction index, which is given by var (interaction index) = var (Dx,1)(d12/Dx,14)∣ + var (Dx,2)(d22/Dx,24. Data were analyzed by R program (http://www.r-project.org/).

ElISA for tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 (IL-1)

RAW 264.7 cells (5×106 cells/well) were seeded in 6-well plates. After 24 h, cells were treated with 1 μg/mL LPS alone or with serial concentrations of test compounds in 2 mL of serum complete media. After another 24 h incubation, the culture media were collected and analyzed for TNF-α and IL-1 levels by ELISA kits, according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Preparation of whole cell lysate

RAW 264.7 cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and collected with cell scrapers from culture plates. The cells were combined with floating cells, if any, and incubated on ice in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 1 % Triton, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4 and 1 μg/mL leupeptin with freshly added protease inhibitor cocktail (Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Set III; Boston Bioproducts, Boston, MA, USA) for 20 min on ice. Cell suspensions were then subjected to sonication (5 s, three times). After further incubation for 20 min on ice, supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 10 min. Protein concentrations were determined by BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA), following manufacturer's instruction.

Immunoblot Analysis

For immunoblot analysis, equal amount of proteins (50 μg) were resolved over 12 % SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking, proteins of interest were probed using different antibodies at manufacturer's recommended concentrations, and then visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Boston Bioproducts, Ashland, MA, USA). Antibodies for iNOS, COX-2, HO-1 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, CA, USA). Anti-β actin antibody was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Quantitative Real-Time Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) Analysis

Total RNA of RAW 264.7 cells were isolated by RNeasy Plus Mini Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). RNA concentrations were determined using NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). From each sample, 0.16 mg of total RNA was converted to single-stranded cDNA which was then amplified by Brilliant II SYBR Green QRT-PCR Master Mix Kit, 1-Step (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) to detect quantitatively the gene expression of iNOS, COX-2, interleukin-1 (IL-1), hemeoxygenase-1 (HO-1) and glyceraldehydes 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (as an internal standard) using Mx3000P QPCR System (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). The primer pairs were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, Iowa, USA) and the sequences are listed in Table 1. Minimum of three independent experiments were carried out, each experiment had triplicate samples for each treatment. The copy number of each transcript was calculated relative to the GADPH copy number using the 2−ΔΔt Method [20].

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

| Gene | Sequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| iNOS | F: 5'-TCC TAC ACC ACA CCA AAC -3' | [30] |

| R: 5'-CTC CAA TCT CTG CCT ATC C -3' | ||

| COX-2 | F: 5'-CCT CTG CGA TGC TCT TCC -3' | [30] |

| R: 5'-TCA CAC TTA TAC TGG TCA AAT CC -3' | ||

| HO-1 | F: 5'-AAG AGG CTA AGA CCG CCT TC -3' | [21] |

| R: 5'-GTC GTC GTC AGT CAA CAT GG -3' | ||

| IL-1 | F: 5'-GAG TGT GGA TCC CAA GCA AT -3' | [21] |

| R: 5'-CTC AGT GCA GGC TAT GGA CCA -3' | ||

| GAPDH | F: 5'-TCA ACG GCA CAG TCA AGG -3' | [30] |

| R: 5'-ACT CCA CGA CAT ACT CAG C -3' |

Statistical Analysis

All data were presented as mean ± SD. Student's t-test was used to test the mean difference between two groups. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) model was used for the comparison of differences among more than two groups. Both 5 % and 1 % significant level were used for the tests.

RESULTS

NBN and SFN synergistically inhibit NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells

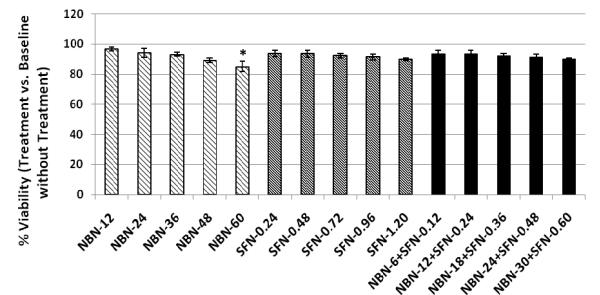

To establish non-toxic dose ranges for NBN and SFN in RAW 264.7 cells, we determined the effects of NBN and SFN on the cell viability, using MTT assay as we described previously [18]. As shown in Figure 1, NBN and SFN at up to 60 μM and 1.2 μM, respectively, did not cause significant decrease on viability of RAW 264.7 cells. We further tested the effects of NBN and SFN in combination on the cell viability. The results showed that the combined treatment with NBN and SFN at 50: 1 ratio (up to 30 μM NBN + 0.6 μM SFN) did not cause significant decrease on the viability of RAW 264.7 cells.

Figure 1.

Cytotoxicity profile of NBN, SFN and their combinations in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Macrophages were seeded in 96-well plates. After 24 h, cells were treated with serial concentrations of NBN, SFN, and their combinations as indicated in the bar graph (the numbers are the concentrations in μM). After another 24 h of incubation, cells were subject to MTT assay for viability. The viability of control cells was set as the reference with a value of 100 %. Results are presented as mean ± SD from six replicates (n = 6). * indicate significant difference (p < 0.01).

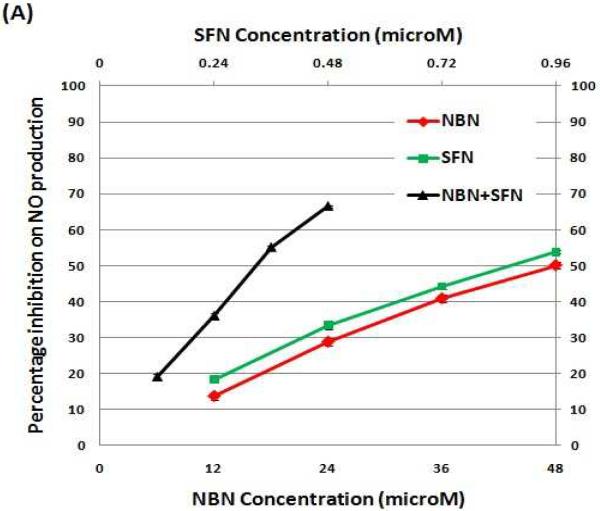

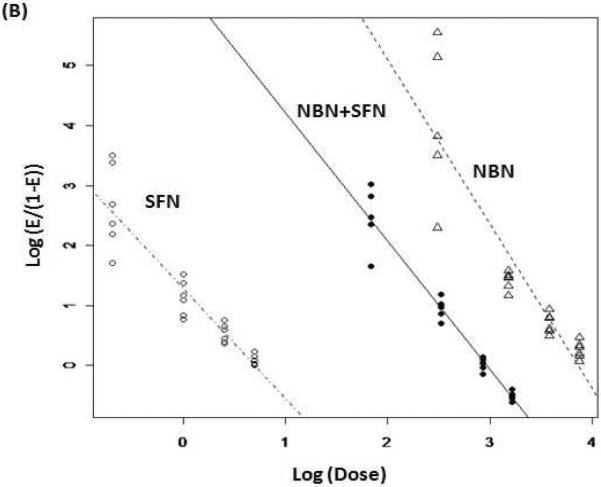

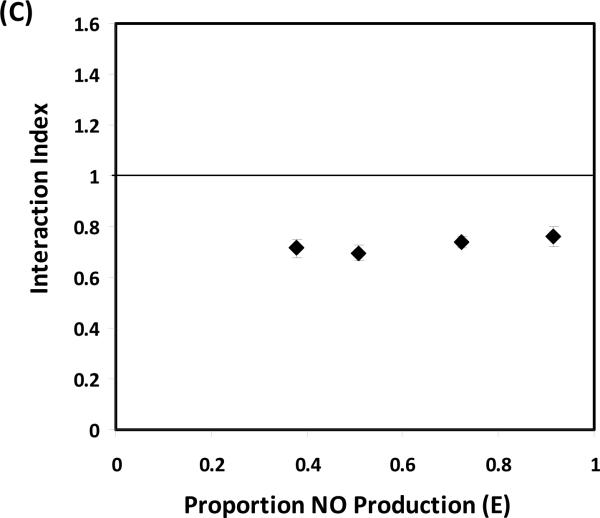

Using the non-toxic dose ranges established, we determined inhibitory effects of NBN, SFN, and their combinations (with NBN and SFN at 50: 1 ratio) on NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. As shown in Figure 2A, NBN caused a dose-dependent inhibition on LPS-induced NO production by 14 %, 29 %, 41 %, and 50 % at 12 μM, 24 μM, 36 μM and 48 μM, respectively (Fig. 2A). Similarly, SFN treatments also resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition on NO production by 18 %, 33 %, 44 %, and 54 % at 0.24 μM, 0.48 μM, 0.72 μM, and 0.96 μM, respectively. To determine the combinational effects of NBN and SFN, LPS-stimulated RAW cells were treated with serial concentrations of NBN + SFN at 50: 1 ratio. As shown in figure 2A, combinations of half dose of NBN with half dose of SFN resulted in stronger inhibition on NO production than the individual treatments with NBN or SFN at full doses. For example, combination of 18 μM of NBN with 0.36 μM of SFN caused a 55 % inhibition on NO production, while 36 μM of NBN alone and 0.72 μM of SFN alone led to only 41 % and 44 % inhibition, respectively. Similarly, combination of 24 μM of NBN with 0.48 μM of SFN caused a 67 % inhibition on NO production, while 48 μM of NBN alone and 0.96 μM of SFN alone led to only 50 % and 54 % inhibition, respectively. It is noteworthy that the inhibitory effect of 18 μM of NBN and 0.36 μM of SFN in combination was even stronger than that produced by 48 μM of NBN alone and similar to that produced by 0.96 μM of SFN alone.

Figure 2.

(A) Percentage of inhibition on NO production by NBN, SFN and their combinations in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. (B) Median effect plot of NBN, SFN and their combination on inhibition of NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. (C) Interaction index plot for the combination effects of NBN and SFN on NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. The cells were treated with LPS (positive control) or LPS plus serial concentrations of NBN, SFN and their combinations as indicated in the figure 2A. After 24 h of incubation, the culture media were collected for NO assay as described in the Method section. The median effect plot was constructed as described in the Method section. The interaction index was calculated based on median effect plot following isobologram analysis as described in the Method section. Results are presented as mean ± SD from six replicates. All treatments showed statistical significance in comparison with the positive control in (A). All dose pairs tested showed interaction index significantly lower than 1 in (C). (P < 0.01, n = 6)

We further determined the mode of interaction between NBN and SFN in inhibiting NO production by using isobologram analysis as we described previously [19]. As shown in Fig. 2B, the median effect plot showed that the linear regression model used in the isobologram analysis well fitted the dose-response relationship of NBN, SFN and their combinations within the concentration ranges exploited herein. Based on the median effect plot, the interaction indexes of each combination dose pair of NBN and SFN were calculated as described in the Methods section. The interaction index was used to determine additivity, synergy, or antagonism of the combination at different doses depending on interaction index = 1, <1 or >1, respectively. As shown in figure 2C, all four dose pairs tested resulted in interaction index lower than 0.8, suggesting a synergistic interaction between NBN and SFN in terms of inhibiting NO production in LPS-stimulated macrophages.

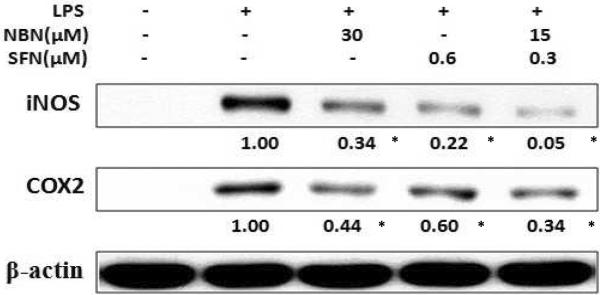

Combination of NBN and SFN decreases protein levels of iNOS and COX-2

Since NO production was synergistically suppressed by combination of NBN and SFN in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells, we next examined the effects of this combination on the protein level of iNOS. We selected to test the effects of 15 μM of NBN + 0.3 μM of SFN in comparison with NBN and SFN alone (The ratio of NBN: SFN is 50: 1 and was the same as that in Fig. 1 and 2). LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells were treated with 30 μM of NBN, 0.6 μM SFN, or their half dose combination (15 μM of NBN + 0.3 μM of SFN) for 24 h, then the protein levels of iNOS in RAW 264.7 were determined by western blotting. The results demonstrated that NBN at 30 μM and SFN at 0.6 μM significantly decreased iNOS protein levels by 66 % and 78 %, respectively, compared to the LPS-treated positive control cells (Fig. 3). However, the combination of NBN and SFN at half doses produced 95 % decrease on iNOS protein level, which was stronger than the effects produced by NBN and SFN at full dose alone. We also determined treatment effects on protein levels of COX-2, an important pro-inflammatory protein. The results showed that NBN at 30 μM, SFN at 0.6 μM, and NBN at 15 μM + SFN at 0.3 μM caused significant decrease on protein levels of COX-2 by 55 %, 40 %, and 66 %, respectively, compared to the LPS-treated positive control cells (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Inhibitory effects of NBN, SFN and their combination on LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 protein expression in RAW 264.7 cells. The cells were seeded in 10-cm dishes for 24 h, and then treated with 1 μg/mL of LPS or LPS plus NBN, SFN and their combination at concentrations indicated in the figure. After 24 h of incubation, cells were harvested for western immunblotting as described in Methods. The numbers underneath of the blots represent band intensity (normalized to β-actin, means of three independent experiments) measured by Image J software. The standard deviations (all within ±15 % of the means) were not shown. β-Actin was served as an equal loading control. “*” indicates statistical significance (P < 0.05, n = 3).

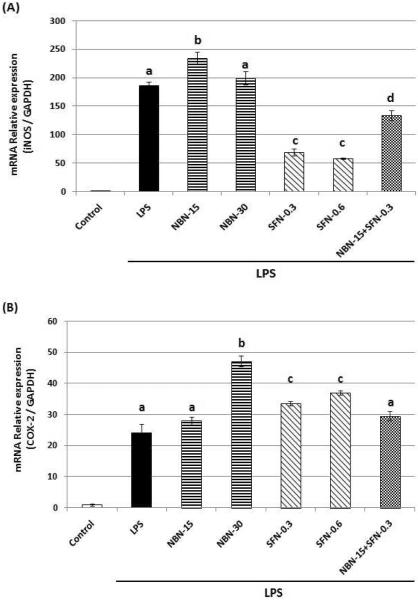

Using qRT-PCR technique, we further analyzed the effects of NBN, SFN, and their combination on the mRNA levels of iNOS and COX-2 after 24 h treatments. As shown in figure 4, the LPS treatments significantly increased the mRNA levels of both iNOS and COX-2, which is consistent with the increased protein expression levels of the two proteins after LPS treatment as shown in figure 3. NBN at 15 or 30 μM did not decrease mRNA levels of iNOS or COX-2, whereas SFN at 0.3 and 0.6 μM caused significant decrease on mRNA level of iNOS by 63 % and 69 %, respectively. However, same SFN treatments did not decrease mRNA level of COX-2. The combination of NBN at 15 μM and SFN at 0.3 μM resulted in a decrease on mRNA level of iNOS by 28 %, but had no effect on mRNA level of COX-2.

Figure 4.

Effects of NBN, SFN and their combination on mRNA levels of iNOS (A) and COX-2 (B) in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. The cells were treated with LPS or LPS plus NBN, SFN and their combination at concentrations indicated in the figure. After 24 h of incubation, total RNA was subjected to quantitative real-time RT-PCR as described in Methods section. The RT products were labeled with SYBR Green dye. Relative iNOS and COX-2 mRNA expression (2−ΔΔCt) was determined by real-time PCR and calculated by the Ct value for iNOS and COX-2 from GAPDH mRNA. ΔΔCt=(Ctt target gene−Ct GAPDH) −(Ct control−Ct GAPDH). Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Different annotations indicate statistical significance (p<0.05, n = 3) by ANOVA.

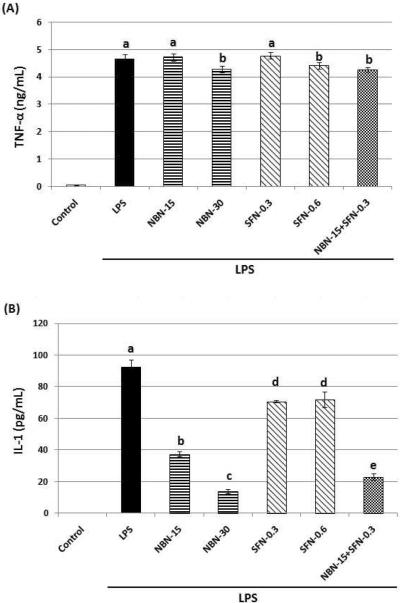

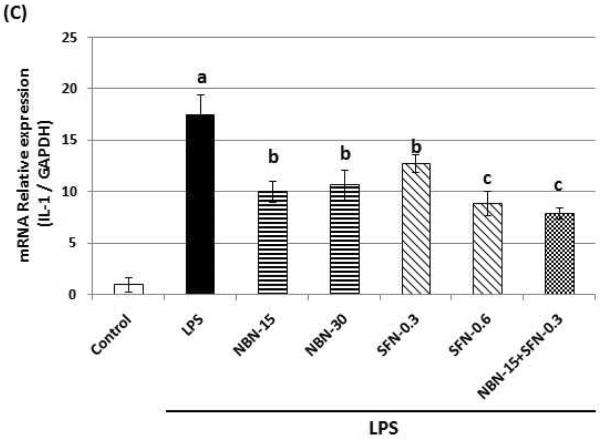

Combination of NBN and SFN decreases protein level of IL-1

Accumulating studies have demonstrated that pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and TNF-α play important roles in the progression of various diseases including cancer. Using ELISA assay, we determined the effects of NBN, SFN and their combination on production of IL-1 and TNF-α in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. As shown in figure 5A and 5B, LPS treatment for 24 h resulted in a significant production of IL-1 and TNF-α in the macrophage cells. NBN at 15 μM and 30 μM dose-dependently suppressed protein levels of IL-1 by 59 % and 85 %, respectively, compared to the LPS-treated positive control cells (Fig. 5B). SFN at 0.3 μM and 0.6 μM showed similar inhibition on IL-1 production by about 22–23 %. The combination of NBN at 15 μM and SFN at 0.3 μM inhibited IL-1 production by 75 % compared to the LPS-treated positive control cells, and this effect was more potent than that caused by SFN at 0.6 μM alone. As shown in figure 5A, NBN, SFN, and their combination showed marginal effects on production of TNF-α, e.g., only NBN at 30 μM, SFN at 0.6 μM, and their half dose combination resulted in a slightly decreased (<10 %) production of TNF-α in comparison with the LPS-treated positive control cells.

Figure 5.

Effects of NBN, SFN and their combination on protein expression levels of TNF-α (A) and IL-1 (B), and on mRNA level of IL-1 (C) in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. The cells were treated with LPS or LPS plus NBN, SFN and their combination at concentrations indicated in the figure. After 24 h of incubation, the culture media were collected and analyzed for protein levels of TNF-α and IL-1 by ELISA. The mRNA level of IL-1 was quantified by qRT-PCR as described in the Method section. The RT products were labeled with SYBR Green dye. Relative IL-1 mRNA expression (2−ΔΔCt) was determined by real-time PCR and calculated by the Ct value for IL-1 from GAPDH mRNA. ΔΔCt=(Ct target gene−Ct GAPDH) −(Ct control−Ct GAPDH). Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Different annotations indicate statistical significance (p<0.05, n = 3) by ANOVA.

Using qRT-PCR technique, we analyzed the effects of NBN, SFN, and their combination on the mRNA levels of IL-1 after 24 h treatments. As shown in figure 5C, NBN at 15 and 30 μM showed similar inhibitory effects (about 40 % inhibition) on the mRNA levels of IL-1 in comparison with the LPS-treated positive control cells. On the other hand, SFN at 0.3 and 0.6 μM showed a dose-dependent inhibition on the mRNA levels of IL-1by 27 % and 49 %, respectively. Furthermore, the combination of NBN at 15 μM and SFN at 0.3 μM led to a 55 % inhibition on the mRNA levels of IL-1 in comparison with the LPS-treated positive control.

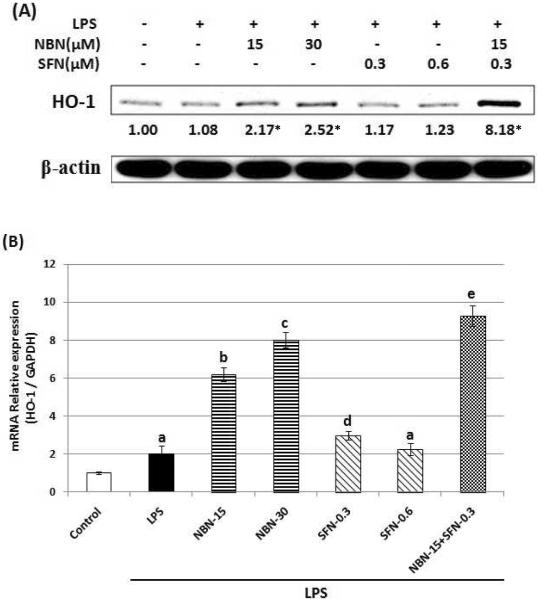

Combination of NBN and SFN increases the protein expression level of HO-1

It was suggested that HO-1, an antioxidant enzyme played a role in regulating inflammation response. Next, we examined the effects of NBN, SFN, and their combination on the protein expression levels of HO-1 in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. As shown in figure 6A, western blotting results demonstrated that NBN at 15 and 30 μM increased protein levels of HO-1 by 2.17 and 2.52-fold, respectively. SFN at 0.3 or 0.6 μM did not cause significant changes on the protein levels of HO-1. Interestingly, the combination of NBN at half dose (15 μM) and SFN at half dose (0.3 μM) drastically increased protein level of HO-1 by 8.18-fold. We further analyzed the effects of NBN, SFN, and their combination on mRNA levels of HO-1 in LPS-stimulated macrophage cells. The results from qRT-PCR demonstrated that NBN at 15 and 30 μM dose-dependently increased the mRNA levels of HO-1 by 3.1 and 4.0-fold in comparison with the LPS-treated positive control cells (Fig. 6B). SFN at 0.3 μM caused a moderate increase in mRNA level of HO-1 by 49 %, while SFN at 0.6 μM did not result in any significant change. Most interestingly, the combination of NBN at 15 μM and SFN at 0.3 μM resulted in a significant increase on mRNA level of HO-1 by 4.64-fold, this effect was more potent than those produced by NBN at 30 μM alone and SFN at 0.6 μM alone.

Figure 6.

(A) Effects of NBN, SFN and their combinations on HO-1 protein expression in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. The cells were seeded in 10-cm dishes for 24 h, and then treated with 1 μg/mL of LPS or LPS plus NBN, SFN and their combination at concentrations indicated in the figure. After 24 h of incubation, cells were harvested for western immunblotting as described in Methods. The numbers underneath of the blots represent band intensity (normalized to β-actin, means of three independent experiments) measured by Image J software. The standard deviations (all within ±15 % of the means) were not shown. β-Actin was served as an equal loading control. “*” indicates statistical significance (P < 0.05, n = 3). (B) Effects of NBN, SFN and their combination on mRNA levels of HO-1 in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. The cells were treated with LPS or LPS plus NBN, SFN and their combination at concentrations indicated in the figure. After 24 h of incubation, total RNA was subjected to quantitative real-time RT-PCR. The RT products were labeled with SYBR Green dye. Relative HO-1 mRNA expression (2−ΔΔCt) was determined by real-time PCR and calculated by the Ct value for HO-1 from GAPDH mRNA. ΔΔCt=(Ct target gene−Ct GAPDH) −(Ct control−Ct GAPDH). Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Different annotations indicate statistical significance (p<0.05, n = 3) by ANOVA.

DISCUSSION

The main objective of this study is to determine the extent to which NBN and SFN potentiate each other and produce enhanced inhibitory effects against inflammation. Our results demonstrated that combinations of NBN and SFN significantly inhibited NO production in LPS-stimulated macrophage cells, and these inhibitory effects were stronger than those produced by NBN or SFN alone at much higher doses (Fig. 2). It is noteworthy that all the doses used for single and combination treatments were non-toxic to macrophage cells. This was to ensure that the inhibitory effects observed on NO production were due to inhibition on inflammation but not due to disruption of normal cellular function. To determine whether the enhanced inhibitory effects from the combination of NBN and SFN were synergistic or additive, we analyzed the mode of interaction between NBN and SFN using an isobologram-based method. Our results clearly demonstrated that the combination of NBN and SFN produced synergistic inhibition on NO production in LPS-stimulated macrophage cells.

To elucidate the molecular mechanism of interaction between NBN and SFN, we investigated their effects on several important pro-inflammatory proteins. The results showed that both NBN and SFN inhibited LPS-induced protein upregulation of iNOS and COX-2, whereas the combination of NBN and SFN at half doses produced even stronger inhibition on protein upregulation of iNOS and COX-2, suggesting a synergistic effect (Fig. 3). We further determined the effects of NBN, SFN, and their combination on mRNA levels of iNOS and COX-2 (Fig. 4). None of NBN, SFN, or their combination decreased mRNA levels of COX-2, suggesting they may decrease protein level of COX-2 by other mechanisms such as modulating translation and/or degradation of COX-2 protein in LPS-stimulated macrophage cells. Interestingly, SFN caused a strong decrease on mRNA levels of iNOS, while NBN did not cause any decrease at all. This result suggested that NBN and SFN had different mechanisms to downregulate iNOS protein, i.e., SFN decreased protein levels of iNOS at least in part by downregulating the transcription of iNOS gene, while NBN decreased protein levels of iNOS by other mechanisms such as inhibiting translation of iNOS mRNA and/or promoting degradation of iNOS protein. Anti-inflammatory effects of SFN have been studied in combination with other dietary components, i.e., curcumin and phenethyl isothiocyanate in LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells, and the results demonstrated synergistic interactions among these compounds in inhibiting inflammatory responses such as elevated iNOS and COX-2 expression levels [21]. Similar to our findings, the synergy between SFN and curcumin or phenethyl isothiocyanate was not due to inhibition of mRNA levels of iNOS or COX-2.

Our results indicated that LPS caused drastic elevation of TNF-α and IL-1 produced by macrophage cells in the culture media. As pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α and IL-1 can increase iNOS transcription by activation of NF-κB that binds to κB element in the NOS promoter [2], and IL-1 can also induce COX-2 expression [22]. It is suggested that high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines can stimulate tumor growth and progression [23]. Our results showed that NBN, SFN, and their combination did not cause a strong inhibition on TNF-α levels in culture media. There was also no change observed on mRNA levels of TNF-α after these treatments (data not shown). On the other hand, NBN caused a strong inhibition on production of IL-1 by macrophage cells, while SFN led to a moderate inhibition on IL-1 (Fig. 5). The combination of NBN and SFN at half doses resulted in a strong inhibition on IL-1, and this inhibitory effect was similar to that caused by the full dose of NBN alone and much stronger than that caused by the full dose of SFN alone. These results suggested that combination of NBN and SFN produced an enhanced inhibitory effect on IL-1 in comparison with NBN or SFN alone. Since IL-1 can induce expression of both iNOS and COX-2, the inhibitory effects of NBN and SFN combination on iNOS and COX-2 may be associated with its inhibition on IL-1.

One of major biological effects of SFN is induction of phase II enzymes, which in turn contributes to cancer preventive activity of SFN. HO-1 is an important phase II antioxidant enzyme, and it has been reported to suppress inflammatory responses and provide protection against the pro-inflammatory effects of toxic agents [24–25]. We investigated the effects of NBN, SFN, and their combination on the protein and mRNA levels of HO-1 in LPS-stimulated macrophage cells. The results demonstrated that full dose of NBN increased HO-1 protein level to 2.5-fold of the control cells. However, at the doses tested, SFN did not significantly increase HO-1 protein level. Most importantly, our results showed that the combination of NBN and SFN at half doses increased HO-1 protein level to 8.18-fold of the control. Consistent with these results on HO-1 protein levels, NBN, SFN and their combination increased mRNA level of HO-1 in the order of NBN + SFN combination > NBN >> SFN. Our results, for the first time, demonstrated that NBN can increase HO-1 protein level in RAW264.7 cells. It was shown that the expression of HO-1 is crucial in inhibiting LPS-induced pro-inflammmatory responses in RAW 264.7 cells [21]. HO-1 can increase cellular anti-oxidant status by generating antioxidants such as bilirubin [26], which can inhibit iNOS protein expression and suppress NO production in RAW 264.7 cells [27]. Moreover, carbon monoxide (CO), a major product of HO-1 activity, was shown to inhibit COX-2 protein expression by suppressing CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) [28]. CO was also shown to inhibit iNOS enzymatic activity thus decrease NO production [29]. Based on the information, our results suggest that the synergistic induction of HO-1 by NBN and SFN in combination play an important role in inhibiting LPS-induced inflammation in RAW264.7 cells.

In summary, combination of NBN and SFN synergistically inhibited LPS-induced inflammation in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells, which was evidenced by lowered NO production and decreased iNOS, COX-2, and IL-1 levels. These effects were associated with synergistic induction of phase II enzyme HO-1 by the NBN + SFN co-treatment. Our results provided new knowledge on the interactions between different dietary bioactive components, which is an important but understudied area.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was supported in part by a NIH grant (CA139174), a USDA Special Grant on Bioactive Foods, and a grant from National Academy of Sciences (PGA-P210858). We thank Noppawat Charoensinphone for helpful discussion and technical support, and the Chinese Scholarship Council (CSC) for providing funding for Shanshan Guo.

Abbreviation

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- HO-1

heme oxygenase-1

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- IL-1

interleukin-1

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NBN

nobiletin

- NO

nitric oxide

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

- SFN

sulforaphane

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Schetter AJ, Heegaard NH, Harris CC. Inflammation and cancer: interweaving microRNA, free radical, cytokine and p53 pathways. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(1):37–49. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hibbs JB., Jr. Synthesis of nitric oxide from L-arginine: a recently discovered pathway induced by cytokines with antitumour and antimicrobial activity. Res. Immunol. 1991;142(7):565–9. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(91)90103-p. discussion 596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohshima H, Bartsch H. Chronic infections and inflammatory processes as cancer risk factors: possible role of nitric oxide in carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res. 1994;305(2):253–64. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)90245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arroyo PL, Hatch-Pigott V, Mower HF, Cooney RV. Mutagenicity of nitric oxide and its inhibition by antioxidants. Mutat .Res. 1992;281(3):193–202. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(92)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miwa M, Stuehr DJ, Marletta MA, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Nitrosation of amines by stimulated macrophages. Carcinogenesis. 1987;8(7):955–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/8.7.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wink DA, Kasprzak KS, Maragos CM, Elespuru RK, Misra M, Dunams TM, Cebula TA, Koch WH, Andrews AW, Allen JS, et al. DNA deaminating ability and genotoxicity of nitric oxide and its progenitors. Science. 1991;254(5034):1001–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1948068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsujii M, Kawano S, DuBois RN. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human colon cancer cells increases metastatic potential. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1997;94(7):3336–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheng H, Shao J, Morrow JD, Beauchamp RD, DuBois RN. Modulation of apoptosis and Bcl-2 expression by prostaglandin E2 in human colon cancer cells. Cancer. Res. 1998;58(2):362–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu XH, Kirschenbaum A, Yao S, Stearns ME, Holland JF, Claffey K, Levine AC. Upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor by cobalt chloride-simulated hypoxia is mediated by persistent induction of cyclooxygenase-2 in a metastatic human prostate cancer cell line. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 1999;17(8):687–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1006728119549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420(6917):860–7. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin N, Sato T, Takayama Y, Mimaki Y, Sashida Y, Yano M, Ito A. Novel anti-inflammatory actions of nobiletin, a citrus polymethoxy flavonoid, on human synovial fibroblasts and mouse macrophages. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;65(12):2065–71. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00203-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshimizu N, Otani Y, Saikawa Y, Kubota T, Yoshida M, Furukawa T, Kumai K, Kameyama K, Fujii M, Yano M, Sato T, Ito A, Kitajima M. Anti-tumour effects of nobiletin, a citrus flavonoid, on gastric cancer include: antiproliferative effects, induction of apoptosis and cell cycle deregulation. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;20(Suppl 1):95–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harada S, Tominari T, Matsumoto C, Hirata M, Takita M, Inada M, Miyaura C. Nobiletin, a polymethoxy flavonoid, suppresses bone resorption by inhibiting NFkappaB-dependent prostaglandin E synthesis in osteoblasts and prevents bone loss due to estrogen deficiency. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011;115(1):89–93. doi: 10.1254/jphs.10193sc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murakami A, Nakamura Y, Torikai K, Tanaka T, Koshiba T, Koshimizu K, Kuwahara S, Takahashi Y, Ogawa K, Yano M, Tokuda H, Nishino H, Mimaki Y, Sashida Y, Kitanaka S, Ohigashi H. Inhibitory effect of citrus nobiletin on phorbol ester-induced skin inflammation, oxidative stress, and tumor promotion in mice. Cancer. Res. 2000;60(18):5059–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin W, Wu RT, Wu T, Khor TO, Wang H, Kong AN. Sulforaphane suppressed LPS-induced inflammation in mouse peritoneal macrophages through Nrf2 dependent pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008;76(8):967–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heiss E, Herhaus C, Klimo K, Bartsch H, Gerhauser C. Nuclear factor kappa B is a molecular target for sulforaphane-mediated anti-inflammatory mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276(34):32008–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104794200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao H, Yang CS. Combination regimen with statins and NSAIDs: a promising strategy for cancer chemoprevention. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;123(5):983–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao H, Yang CS, Li S, Jin H, Ho C-T, Patel T. Monodemethylated polymethoxyflavones from sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) peel inhibit growth of human lung cancer cells by apoptosis. Mol. Nutr. Food. Res. 2009;53(3):398–406. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200800057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao H, Zhang Q, Lin Y, Reddy BS, Yang CS. Combination of atorvastatin and celecoxib synergistically induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;122(9):2115–24. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheung KL, Khor TO, Kong AN. Synergistic effect of combination of phenethyl isothiocyanate and sulforaphane or curcumin and sulforaphane in the inhibition of inflammation. Pharm. Res. 2009;26(1):224–31. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9734-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dinarello CA. The paradox of pro-inflammatory cytokines in cancer. Cancer. Metastasis. Rev. 2006;25(3):307–13. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9000-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin WW, Karin M. A cytokine-mediated link between innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117(5):1175–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI31537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen XL, Kunsch C. Induction of cytoprotective genes through Nrf2/antioxidant response element pathway: a new therapeutic approach for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2004;10(8):879–91. doi: 10.2174/1381612043452901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li N, Alam J, Venkatesan MI, Eiguren-Fernandez A, Schmitz D, Di Stefano E, Slaughter N, Killeen E, Wang X, Huang A, Wang M, Miguel AH, Cho A, Sioutas C, Nel AE. Nrf2 is a key transcription factor that regulates antioxidant defense in macrophages and epithelial cells: protecting against the proinflammatory and oxidizing effects of diesel exhaust chemicals. J. Immunol. 2004;173(5):3467–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin CC, Liu XM, Peyton K, Wang H, Yang WC, Lin SJ, Durante W. Far infrared therapy inhibits vascular endothelial inflammation via the induction of heme oxygenase-1. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008;28(4):739–45. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang WW, Smith DL, Zucker SD. Bilirubin inhibits iNOS expression and NO production in response to endotoxin in rats. Hepatology. 2004;40(2):424–33. doi: 10.1002/hep.20334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suh GY, Jin Y, Yi AK, Wang XM, Choi AM. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein mediates carbon monoxide-induced suppression of cyclooxygenase-2. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2006;35(2):220–6. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0154OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorup C, Jones CL, Gross SS, Moore LC, Goligorsky MS. Carbon monoxide induces vasodilation and nitric oxide release but suppresses endothelial NOS. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277(6 Pt 2):F882–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.6.F882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan MH, Lai CS, Wang YJ, Ho C-T. Acacetin suppressed LPS-induced up-expression of iNOS and COX-2 in murine macrophages and TPA-induced tumor promotion in mice. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006;72(10):1293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]