Abstract

Imaging a phantom of known dimensions is a widely used and simple method for calibrating MRI gradient strength. However, full-range characterization of gradient response is not achievable using this approach. Measurement of the apparent diffusion coefficient of a liquid with known diffusivity allows for calibration of gradient amplitudes across a wider dynamic range. An important caveat is that the temperature-dependence of the liquid’s diffusion characteristics must be known, and the temperature of the calibration phantom must be recorded. In this report we demonstrate that the diffusion coefficient of ethylene glycol is well-described by Arrhenius-type behavior across the typical range of ambient MRI magnet temperatures. Because of ethylene glycol’s utility as an NMR chemical-shift thermometer, the same 1H MR spectroscopy measurements that are used for gradient calibration also simultaneously “report” the sample temperature. The high viscosity of ethylene glycol makes it well-suited for assessing gradient performance in demanding diffusion-weighted imaging and spectroscopy sequences.

Introduction

In recent years, attempts to explore tissue microstructure in vivo have been focused on the MR diffusion behavior of water and slowly-diffusing, compartmentalized metabolites over an extended range of b values and diffusion times (1–3). Such protocols require strong diffusion gradients and high gradient duty cycles. The interpretation of biophysical parameters of interest assumes accurate calibration and robust performance of the MR gradient hardware.

Perhaps the simplest and most commonly-employed means of calibrating gradient amplitudes in MRI systems involves measurement of the apparent size of a standard phantom of known dimensions (4). The gradient amplitude in the image readout direction is considered to be properly adjusted when the apparent size of the phantom matches its known physical dimensions. However, this approach typically does not allow for characterization of the gradient performance over its full dynamic range.

In principle, MR diffusion measurements, using a fluid phantom of known diffusion coefficient, allow for assessment of the gradient performance over the full dynamic range of the gradient-amplifier/gradient-coil system. Because water is readily available and its diffusion coefficient has been investigated extensively (5), it is often chosen to test gradient performance and calibrate gradient amplitudes. However, as noted by Tofts, et al. (6), the relatively large diffusion coefficient of water is a limitation of its use in this role. A number of other, more viscous fluids have also been characterized as possible quality assurance (QA) standards in MR diffusion measurements (5,6). However, because the diffusion coefficients of these fluids vary with temperature, a means to monitor and/or regulate temperature in the phantom sample is required.

Most high-resolution NMR systems are equipped with variable temperature units that allow for accurate and precise control of sample temperature. However, imaging systems typically provide no control of sample temperature, necessitating measures such as blowing heated air into the bore of the magnet to keep the sample at constant, warm temperature. Further, for accurate calibration of diffusion measurements an MR-compatible temperature monitoring system is required.

It has been long recognized that ethylene glycol can be employed as an NMR thermometer, the chemical-shift difference between its −OH and −CH2− resonances being temperature-dependent (7). Over the range from 273 to 416 K, this NMR chemical-shift thermometer is well-characterized and accurately measures temperature to within ± 0.5 °C (7,8). However, the exploration of the temperature-dependence of the diffusion coefficient of ethylene glycol in the literature is limited to just two reports (9,10).

In this report, we present temperature-dependent diffusion data for ethylene glycol over the range of ambient temperatures likely to be encountered in MRI scanners. As examples, we also describe the use of ethylene glycol as a phantom for testing gradient hardware performance in demanding diffusion-weighted PRESS spectroscopy measurements and single-shot diffusion-weighted EPI. The slow diffusion of ethylene glycol ensures adequate signal-to-noise ratio with even the highest b-values employed in diffusion MR protocols. In addition, the high viscosity reduces systematic errors due to flow and convection effects (6,11). Lastly, the sample simultaneously “reports” its temperature in the spectroscopy measurement.

Methods

Fresh aliquots of anhydrous, high-purity (≥ 99.8% pure) ethylene glycol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were placed in the outer annulus of a 10-mm (o.d.) NMR tube with a coaxial insert (Wilmad LabGlass, Vineland, NJ) containing deionized water. While ethylene glycol is hygroscopic, trace amounts of water have only a small effect on its diffusion coefficient (10). Measurements were carried out in two 4.7-T Agilent DirectDrive small-animal MRI systems which, owing to differences in the chilled water supply to their gradient sets, had ambient bore temperatures that differed by ~ 5°C (13.9 °C and 19.3 °C, respectively). Diffusion measurements over a range of temperatures from 287.0 – 303.8 K (13.9 – 30.6 °C) were accessible by blowing heated air down the magnet bore. All samples were temperature equilibrated for a minimum of one hour prior to MR experiments.

A non-localized, Stejskal-Tanner spin-echo sequence with half-sine-shaped gradients was employed to obtain diffusion data for ethylene glycol and water. Typical acquisition parameters included TR = 20 s, acquisition time = 4 s, sweep width = 4000 Hz, δ = 5 – 7 ms, Δ = 51.25 – 300 ms, Gdiff = 0 – 35 G/cm, 16 dummy scans to reach steady state, and two signal averages per b value (with longer Δ and δ required in the MRI system with lower maximum gradient strength to achieve equivalent b values). The extent of diffusion-weighting in this series of measurements was calculated according to standard methods (12),

| [1] |

Sample temperature was determined from the chemical-shift difference of the ethylene glycol resonances (8):

| [2] |

wherein T(K) is the absolute temperature in Kelvin, ΔνEthGlyc is the frequency difference (in Hz) between the ethylene glycol −OH and −CH2− resonances and νo is the resonance frequency (in Hz) for 1H in the MR magnet.

Water was used as a primary reference for the diffusion measurements to ensure proper gradient-amplitude scaling. For this purpose, we relied on the non-Arrhenius diffusion coefficient vs. temperature relationship recommended by Holz, et al. (5):

| [3] |

Because of the disparity between the diffusion coefficients of water and ethylene glycol (e.g., at 298K, DH2O = 2.30 µm2/ms and DEthGlyc = 0.0882 µm2/ms, vide infra), on each of two MRI systems, two sets of diffusion measurements were performed with identical gradient amplitudes (Gdiff) and durations (δ) for each coaxial water/ethylene glycol sample at each temperature. The two sets of measurements, differing in their inter-gradient pulse spacing (Δ), allowed evaluation of the H2O diffusion coefficient in a series of measurements (with short Δ, b values: 0 – ~ 1.5 ms/µm2) that covered essentially the full range of Gdiff values explored. In the second set of measurements (with longer Δ, but the same range of Gdiff values), the diffusion coefficients of both water (using b-values: 0 – 1.5 ms/µm2) and ethylene glycol (with b values 0 – ~ 12 ms/µm2) were estimated. Since the data were well behaved and only very small, non-systematic differences in the 1H2O diffusion coefficients were observed between the two sets of measurements, the use of secondary diffusion standards with D intermediate between water and ethylene glycol was determined to be unnecessary (11).

Using the Bayes Analyze module of the Bayesian Analysis software suite (http://bayesiananalysis.wustl.edu/index.html), the time-domain FID data were modeled to estimate the amplitudes of the ethylene glycol (−OH and −CH2−) and water resonances in each spectrum (13). Diffusion coefficients (as well as T1 and T2 values) were estimated with the Bayesian Exponential Analysis package (14,15), modeling the data as a monoexponential decay function.

Data were acquired with diffusion-sensitizing gradients of both positive and negative polarities. In estimating diffusion coefficients, the geometric mean of the two sets of measurements for each targeted b value was computed and the resulting dataset, consisting of geometric mean signal intensity vs. b value, was used in subsequent calculations to ensure cancellation of unwanted cross-terms between the applied diffusion gradients and background gradients (16,17). Diffusion coefficients were calculated separately from the data acquired with positive and negative diffusion gradients to evaluate gradient amplitude as a function of polarity.

The spin-lattice relaxation time constants, T1, for the ethylene glycol resonances were determined via inversion-recovery experiments with an array of twenty inversion times, τi, exponentially spaced over the range between 5 ms and 15 s. Resonance intensities (as determined via application of the Bayes Analyze package to the time-domain FID) were modeled as a single exponential decay plus a constant:

| [4] |

For determination of the T2 relaxation time constants, an array of 25 exponentially-spaced echo times (20 ms – 2 s) were employed in Hahn spin-echo measurements (18). The resulting resonance intensity vs. TE data was modeled as a single exponential decay:

| [5] |

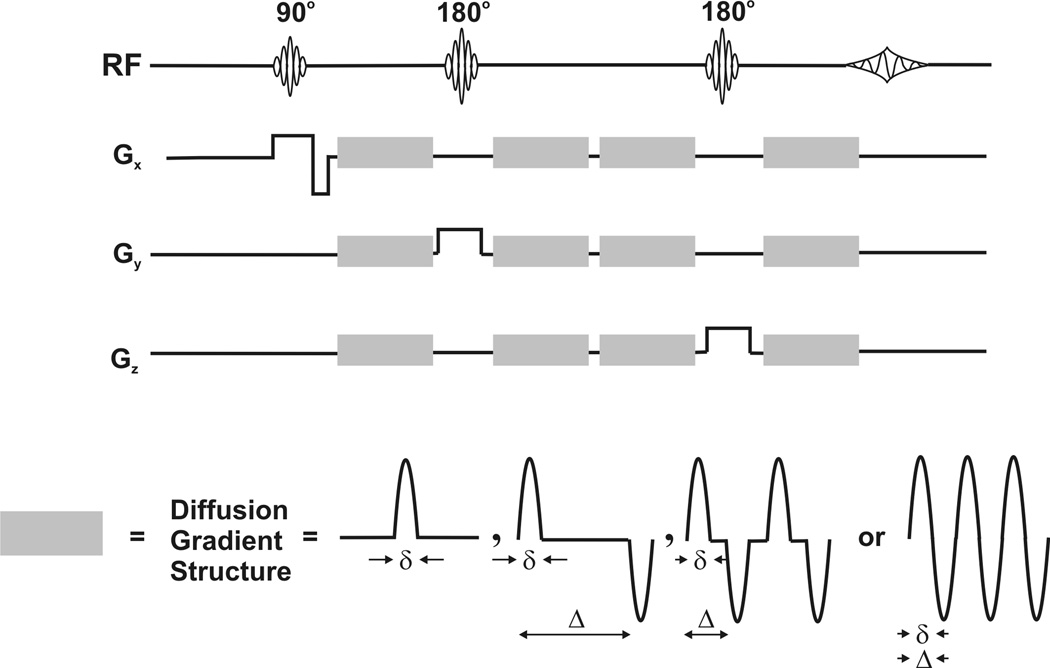

Investigation of gradient performance in more demanding, high duty-cycle diffusion-weighted PRESS sequences (Figure 4), an application of interest in this laboratory, was carried out using a sample of pure ethylene glycol. These range from relatively low-duty, diffusion-weighted PRESS with monopolar, half-sine-shaped diffusion-weighting gradients (19) to higher-duty PRESS localization with oscillating gradients (20).

Figure 4.

Diffusion-weighted PRESS sequences used for testing gradient performance with increasing duty cycle. In these sequences, built with half-sine-shaped gradient structures, the diffusion time is given by tdiff = Δ − δ/4 and b = n·(4/π2)·γ2·Gdiff2·δ2·tdiff, wherein n is the number of gradient-lobe pairs or oscillating gradient cycles (20). For diffusion in a homogeneous, unbounded medium, (e.g., ethylene glycol) the narrow-pulse approximation remains applicable (25).

For single-shot, diffusion-weighted EPI of an ethylene glycol phantom, a standard frequency-selective “fat” saturation protocol was used to reduce the 1H MR signal to a single spectral component, which is a requirement for artifact-free EPI images. The sample temperature was determined from the observed frequency difference between −OH and −CH2− resonances with a simple, non-localized pulse-and-acquire spectroscopy measurement. The observed frequency difference was also used to set the resonance offset for saturation of the −OH resonance (an 8-ms Gaussian RF pulse was used, followed by application of spoiler gradients). The EPI images were generated from the remaining −CH2− magnetization. A spin-echo preparation, with a pair of diffusion-weighting trapezoidal gradient pulses applied in the phase-encode direction, was used for the EPI acquisition. Other EPI imaging parameters included TR = 5 s, TE = 90 ms, eight dummy scans, and three signal averages. An 18 × 18 mm2 (64 × 64) field-of-view was used with a 1-mm slice thickness.

Results

Over the temperature range investigated here, 13.8 – 30.6 °C, the diffusivity of ethylene glycol (DEthGlyc) is well-described by an Arrhenius expression, as shown in Fig. 1. The relationship between DEthGlyc (in µm2/ms) and the absolute temperature (T) in Kelvin is given by:

| [6] |

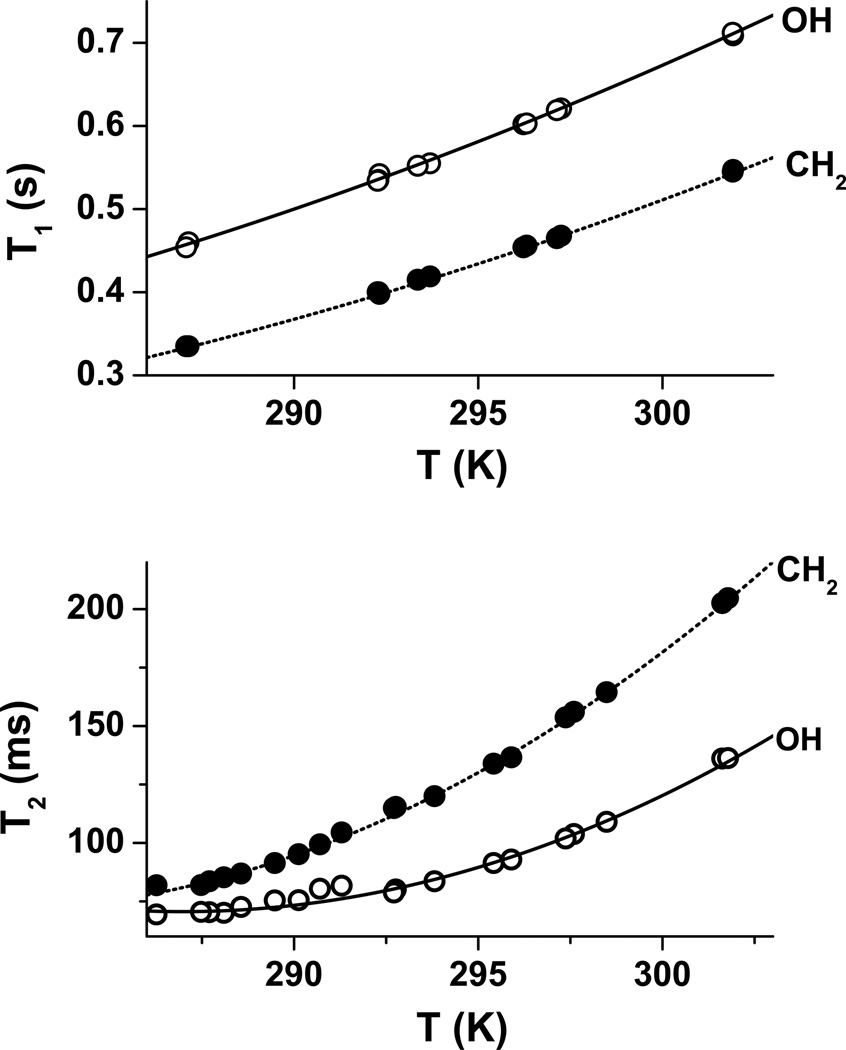

Over the same temperature range, the T1 and T2 relaxation time constants at 4.7 T for the ethylene glycol −OH and −CH2− resonances as a function of absolute temperature, T (in Kelvin), are described in Eqs. [7]–[10] and shown graphically in Figure 2. For the T1 relaxation times,

| [7] |

and

| [8] |

At 298 K, the corresponding T1 values are 0.65 s (−OH) and 1.35 s (−CH2−).

Figure 1.

Arrhenius plot of ln DEthGlyc with D in units of µm2/ms over the temperature range from 13.9 – 30.6 °C (n = 14). Eight different aliquots of ethylene glycol were used. Inset: All extant diffusion data for ethylene glycol plotted on a single Arrhenius plot. The data from Reference (9) were derived from porous frit diffusion experiments, while those from (10) come from NMR diffusion measurements.

Figure 2.

top: T1(s) and, bottom: T2(ms) relaxation time constants for the ethylene glycol −OH and −CH2− resonances as a function of temperature at Bo = 4.7 T.

The T2 relaxation times have a more pronounced quadratic temperature dependence.

| [9] |

| [10] |

At 298 K, the corresponding T2 values are 144 ms (−OH) and 120 ms (−CH2−).

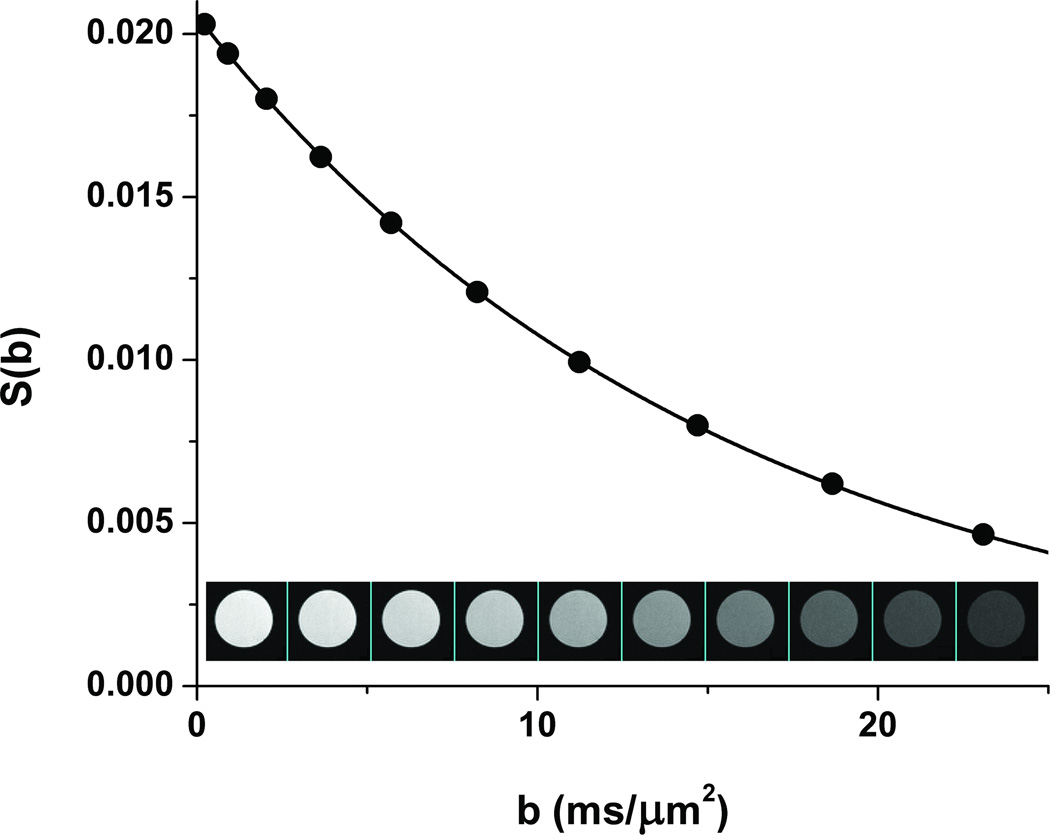

Ethylene glycol can also be used for quality assurance in diffusion-weighted, single-shot EPI experiments. Figure 3 shows an example from one of our small-animal MRI systems. Based on a pulse-and-acquire spectroscopy measurement, the sample temperature was determined to be 290.7K (ΔνEthGlyc = 348.2 Hz). From Eq. [6], the expected diffusion coefficient for ethylene glycol at this temperature is 0.0649 µm/ms2, in close agreement with that determined experimentally, 0.0645 µm/ms2 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Diffusion measurements on an ROI within a sample of ethylene glycol using single-shot diffusion-weighted EPI. The sample temperature (290.7 K) was determined via a pulse-and-acquire 1H NMR spectrum. The resulting DEthGlyc of 0.0645 µm2/ms is in very close agreement with the value of 0.0649 µm2/ms calculated from Eq. [6].

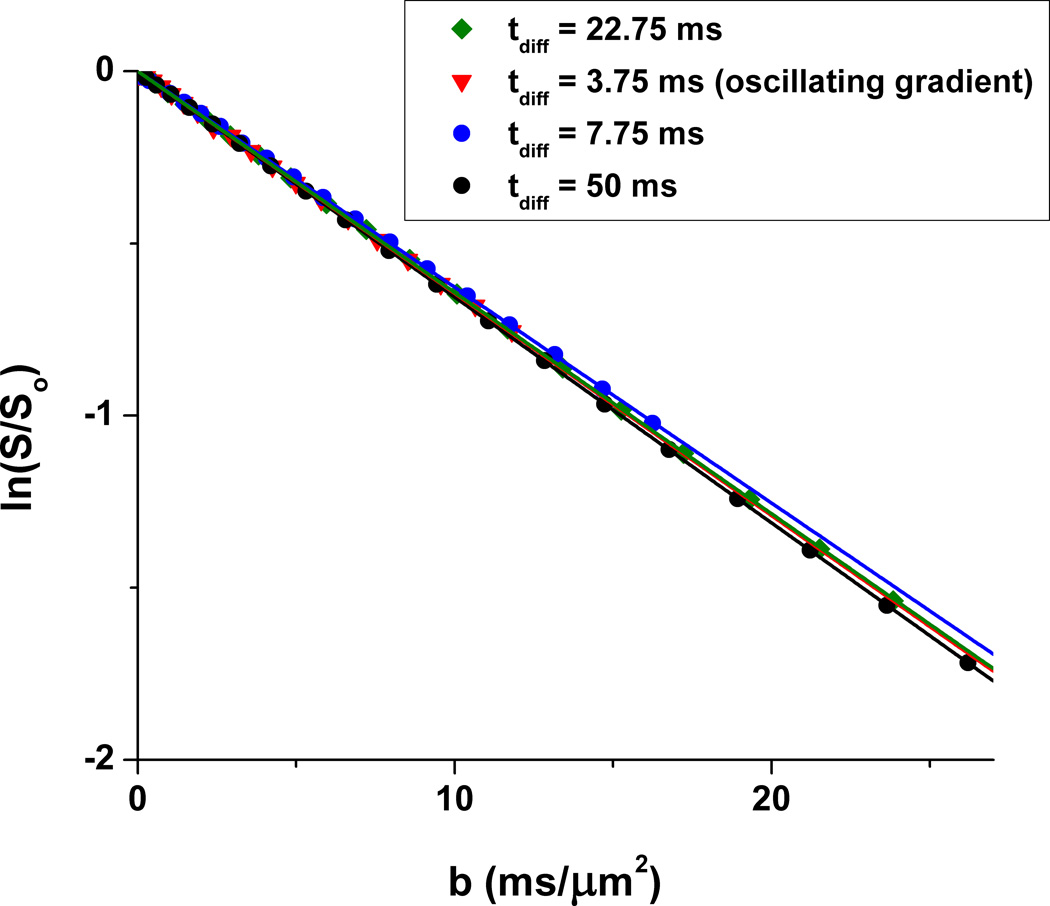

Results for a series of diffusion-weighted PRESS spectroscopy sequences (Fig. 4), which place increasing demand on gradient hardware, are presented in Fig. 5. There is no apparent systematic variation of DEthGlyc with increasing gradient duty cycle across this series of measurements. The highly linear appearance of the data in the semi-log plot of ln(S/So) vs. b value indicates robust gradient hardware performance over the full range explored.

Figure 5.

Gradient performance tests on a sample of ethylene glycol at 290.7 K employing the diffusion-weighted PRESS sequences shown in Fig. 4. A 5 × 5 × 5 mm3 voxel was interrogated. Diffusion gradient amplitudes ranged from 0 – 35 G/cm, with δ = 5 ms. The diffusion time is tdiff = Δ − δ/4. The resulting DEthGlyc values ranged between 0.0625 µm2/ms (−3.7 % error vs. the value 0.0649 µm2/ms calculated from Eq. [6]) and 0.0656 µm2/ms (+1.1 % error).

Discussion and Conclusions

Our results for the temperature-dependence of DEthGlyc show good concordance with the data available in the literature on this topic (9,10), as depicted in the inset of Fig. 1. There are several reports in the literature on the ethylene glycol NMR thermometer (7,8,21), and these contain small differences in the reported thermometric relationships. We chose to use Eq. [1] from reference (8) because it covers the range of temperatures used in this study and agrees very closely, within ± 0.5K, with the careful studies carried out by Van Geet (7). Methanol is another popular 1H NMR thermometer (7,8), but its diffusion coefficient at room temperature is similar to that of free water (22). This high diffusivity limits its use for quality assurance to low b values.

We acquired diffusion data with motion-sensitizing gradients of both positive and negative polarities to avoid the possibility of spurious contributions to the estimated b value arising from cross-terms between residual, unshimmed, Bo inhomogeneity and the applied pulsed-gradient waveforms (16,17). At least one report in the literature has described differences in gradient amplitudes on the order of 1% for positive and negative polarities along a given Cartesian axis (23). We have observed such differences as well (data not shown); however, on our systems, these differences are only systematic for a given sample. That is, shimming determines which polarity of gradient pulse produces the larger observed diffusion coefficient, an effect attributed to cross-terms between static background gradients and the pulsed diffusion gradients (16,17).

The design of the localized spectroscopy sequences in Fig. 4 (i.e., the use of half-sine-shaped diffusion gradients) was informed by the work of Price, et al. (24), which advocates the use of half-sine gradients over trapezoidal gradient structures due to their better pulse-to-pulse reproducibility, reduced sample vibrations, and reduced eddy-current production.

The data of Fig. 5 provide two valuable diagnostic indicators of overall gradient performance. The absence of any systematic variation in ethylene glycol diffusion coefficient, as measured with sequences described in Fig. 4, demonstrates that the gradient amplifiers do not “droop” with increasingly demanding diffusion gradient duty cycles. The linear appearance of the semi-log plots of DEthGlyc vs. b value shows that the diffusion-gradient pulses are well-matched; mismatches would be manifest as negative deviations from linearity with higher b values (24).

Ethylene glycol, with its built-in temperature-reporting feature, is a convenient phantom material for testing gradient calibration and performance in diffusion-weighted MR sequences that require high b values. In tests of gradient performance in single-shot, diffusion-weighted EPI, a non-localized 1H NMR spectrum must first be acquired to determine sample temperature based on the observed −OH/−CH2− frequency difference. The spectroscopy measurement also guides the selection of the offset frequency for chemical-shift-selective saturation of one of the ethylene glycol resonances to reduce the 1H MR signal to a single spectral component, which is a requirement for echo-planar images.

Acknowledgments

Support for this work was provided by NIH NCRR Shared Instrumentation Grant Program (S10 RR022658) and NIBIB (5R01EB002083-11). We are grateful to G. Larry Bretthorst for assistance with Bayesian modeling. Free download of the Bayesian toolbox is available at http://bayesiananalysis.wustl.edu/.

References

- 1.Kroenke CD, Ackerman JJH, Yablonskiy DA. On the Nature of the NAA Diffusion Attenuated MR Signal in the Central Nervous System. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2004;52:1052–1059. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assaf Y, Cohen Y. Non-Mono-Exponential Attenuation of Water and N-Acetyl Aspartate Signals Due to Diffusion in Brain Tissue. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1998;131:69–85. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1997.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gore JC, Xu J, Colvin DC, Yankeelov TE, Parsons EC, Does MD. Characterization of tissue structure at varying length scales using temporal diffusion spectroscopy. NMR in Biomedicine. 2010;23:745–756. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Och JG, Clarke GD, Sobol WT, Rosen CW, Mun SK. Acceptance testing of magnetic resonance imaging systems: Report of AAPM Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Task Group No. 6. Medical Physics. 1992;19(1):217–229. doi: 10.1118/1.596903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holz M, Heil SR, Sacco A. Temperature-dependent self-diffusion coefficients of water and six selected molecular liquids for calibration in accurate 1H NMR PFG measurements. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2000;2:4740–4742. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tofts PS, Lloyd D, Clark CA, Barker GJ, Parker GJM, McConville P, Baldock C, Pope JM. Test Liquids for Quantitative MRI Measurements of Self-Diffusion Coefficient. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2000;43:368–374. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200003)43:3<368::aid-mrm8>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Geet AL. Calibration of the Methanol and Glycol Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Thermometers with a Static Thermistor Probe. Analytical Chemistry. 1968;40(14):2227–2229. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amman C, Meier P, Merbach AE. A Simple Multinuclear NMR Thermometer. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1982;46:319–321. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell RD, Moore JW, Wellek RM. Diffusion Coefficients of Ethylene Glycol and Cyclohexanol in the Solvents Ethylene Glycol, Diethylene Glycol, and Propylene Glycol as a Function of Temperature. Journal of Chemical and Engineering Data. 1971;16(1):57–60. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ambrosone L, D'Errico G, Sartorio R, Costantino L. Dynamic properties of aqueous solutions of ethylene glycol oligomers as measured by the pulsed gradient spin-echo NMR technique at 25°C. J Chem Soc, Faraday Trans. 1997;93(22):3961–3966. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holz M, Weingartner H. Calibration in Accurate Spin-Echo Self-Diffusion Measurements Using 1H and Less-Common Nuclei. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1991;92:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Graaf R. In Vivo NMR Spectroscopy. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bretthorst GL. Bayesian Analysis. III. Applications to NMR signal detection, model selection, and parameter estimation. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1990;88(3):571–595. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bretthorst GL. How accurately can parameters from exponential models be estimate? A Bayesian view. Concepts in Magnetic Resonance, Part A. 2005;27A(2):73–83. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bretthorst GL, Hutton WC, Garbow JR, Ackerman JJH. Exponential parameter estimation (in NMR) using Bayesian probability theory. Concepts in Magnetic Resonance, Part A. 2005;27A(2):55–63. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong X, Dixon WT. Measuring Diffusion in Inhomogeneous Systems in Imaging Mode Using Antisymmetric Sensitizing Gradients. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1992;99:561–570. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neeman M, Freyer JP, Sillerud LO. Pulsed-Gradient Spin-Echo Diffusion Studies in NMR Imaging. Effects of the Imaging Gradients on the Determination of Diffusion Coefficients. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1990;90:303–312. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahn E. Spin Echoes. Physical Review. 1950;80(4):580–594. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicolay K, Braun KPJ, de Graaf RA, Dijkhuizen RM, Kruiskamp MJ. Diffusion NMR Spectroscopy. NMR in Biomedicine. 2001;14:94–111. doi: 10.1002/nbm.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Does M, Parsons E, Gore J. Oscillating Gradient Measurements of Water Diffusion in Normal and Globally Ischemic Rat Brain. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2003;49:206–215. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan ML, Bovey FA, Cheng HN. Simplified Method of Calibrating Thermometric Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Standards. Analytical Chemistry. 1975;47(9):1703–1705. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurle RL, Easteal AJ, Woolf LA. Self-diffusion in Monohydric Alcohols under Pressure: Methanol, Methan(2H)ol and Ethanol. J Chem Soc, Faraday Trans 1. 1985;81:769–779. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagy Z, Weiskopf N, Alexander DC, Deichmann R. A Method for Improving the Performance of Gradient Systems for Diffusion-Weighted MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2007;58:763–768. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Price WS, Hayamizu K, Ide H, Arata Y. Strategies for Diagnosing and Alleviating Artifactual Attenuation Associated with Large Gradient Pulses in PGSE NMR Diffusion Measurements. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1999;139:205–212. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yablonskiy DA, Sukstanskii AL. Theoretical models of the diffusion-weighted MR signal. NMR in Biomedicine. 2010;23:661–683. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]