Abstract

Considerable data support the idea that Foxo1 drives the liver transcriptional program during fasting and is inhibited by Akt after feeding. Mice with hepatic deletion of Akt1 and Akt2 were glucose intolerant, insulin resistant, and defective in the transcriptional response to feeding in liver. These defects were normalized upon concomitant liver–specific deletion of Foxo1. Surprisingly, in the absence of both Akt and Foxo1, mice adapted appropriately to both the fasted and fed state, and insulin suppressed hepatic glucose production normally. Gene expression analysis revealed that deletion of Akt in liver led to constitutive activation of Foxo1–dependent gene expression, but once again concomitant ablation of Foxo1 restored postprandial regulation, preventing its inhibition of the metabolic response to nutrient intake. These results are inconsistent with the canonical model of hepatic metabolism in which Akt is an obligate intermediate for insulin’s actions. Rather they demonstrate that a major role of hepatic Akt is to restrain Foxo1 activity, and in the absence of Foxo1, Akt is largely dispensable for hepatic metabolic regulation in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

Eukaryotic organisms have developed mechanisms of varying complexity to deal with periods of starvation and nutritional abundance. In mammals, the obligate requirement for at least some simple carbohydrate at all times is fulfilled during fasting by liver, which initially breaks down glycogen before transitioning to gluconeogenesis as a means to release glucose into circulation. Just as phylogenetically conserved adaptations to fasting are critical to survival, a complex interplay of hormonal, neural and nutritional signals drive the coordinated response to feeding. Ultimately, the ability of an organism to survive dietary deprivation depends on the effectiveness of its nutrient storage during the postprandial state as well as the mobilization of those nutrients.

Almost since its discovery, researchers have recognized the importance of insulin to the metabolic transition that accompanies feeding1. In recent years, there has emerged a clear picture of the insulin signaling pathway, beginning with insulin’s interaction with its receptor, which phosphorylates the scaffolding protein family, insulin receptor substrate. This initiates a linear signaling cascade that culminates in the phosphorylation of Akt protein kinases1–10. Once activated, Akt kinases utilize several distinct downstream pathways to modulate metabolism. One branch involves phosphorylation and inactivation of the Tsc1–Tsc2 complex, leading to activation of the mTorc1 complex and its immediate downstream target p70 S6 kinase, which promotes protein translation and cell growth11,12. Activation of mTorc1 correlates with and is most likely necessary for insulin–induced accumulation of the sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1 (Srebf1, also known as Srebp1c), which drives the lipogenic program12–17. On another branch, Akt phosphorylates and inactivates glycogen synthase kinase 3 (Gsk3α, Gsk3β), resulting in glycogen synthase activation and glycogen accumulation, as well as reduced phosphorylation and degradation of Srebf118. On the third branch, Akt phosphorylates and inactivates the Foxo family of transcription factors, which is responsible for the decrease in transcription of genes encoding gluconeogenic enzymes19–23.

In liver, Foxo1 collaborates with the co–activators peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma co–activator 1α (Ppargc1a) and Creb regulated transcription co–activator 2 (Crtc2) to increase coordinately the expression of the genes glucose–6–phosphatase, catalytic subunit (G6pc) and cytosolic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 (Pck1)24–26. It is generally accepted that Foxo1 is active during fasting, inactivated by Akt–mediated phosphorylation after feeding, and that the antagonism of Foxo1 by Akt is the predominant mechanism by which insulin suppresses hepatic glucose output after a meal1,26–29. Data contributed by a number of laboratories in support of this model include the following observations: 1) insulin induces phosphorylation and activation of Akt after feeding; 2) activated Akt phosphorylates Foxo1 at T24, S253, and S316 of the mouse protein; 3) phosphorylated Foxo1 translocates out of nucleus; and 4) transcription of Foxo1–dependent genes, such as G6pc, Pck1, insulin–like growth factor binding protein 1 (Igfbp1), and insulin receptor substrate 2 (Irs2), is reduced19–22,25–27,30. Nonetheless, there are several gaps and apparent contradictions in the knowledge concerning Foxo1. For example, liver–specific ablation of Foxo1 results in mildly improved insulin sensitivity and hypoglycemia occurs only after prolonged fasting in adult mice. In addition, in these mice there is a decrease in expression of Irs2, G6pc, Pck1, Ppargc1a, and Igfbp1, but little or no change in the expression of glucokinase (Gck) or lipogenic genes31,32. Perhaps one reason for confusion regarding the physiological role of Foxo1 is that much of the information about its functions in hepatic metabolism has been obtained from insulin resistant livers, in which unchecked Foxo1 activation results in profound metabolic abnormalities in gluconeogenesis as well as lipid metabolism and glycogen storage6,31. Antagonizing or reducing hepatic Foxo1 activity in insulin–resistant mice significantly improves glucose tolerance and insulin responsiveness6,23,28,31,33,34. Dramatic examples of this are studies using the insulin receptor knockout mice or mice with liver–specific knockout of both insulin receptor substrate, Irs1 and Irs2, for which concomitant deletion of hepatic Foxo1 reverses much of the metabolic defect6,31.

Current data support a model in which Akt is an obligate insulin signaling intermediate that suppresses expression of genes encoding gluconeogenic enzymes via inhibition of Foxo1, which is active during fasting. In this study, we test an alternative interpretation of these data. We found that inhibition of Foxo1 is a major role of hepatic Akt, such that once Foxo1 is removed, most of normal metabolic regulation is maintained in the absence of liver Akt. These data refute the notion that insulin signals through Akt under all conditions but rather suggest an alternative, previously unrecognized mechanism through which liver responds to nutrients and insulin.

RESULTS

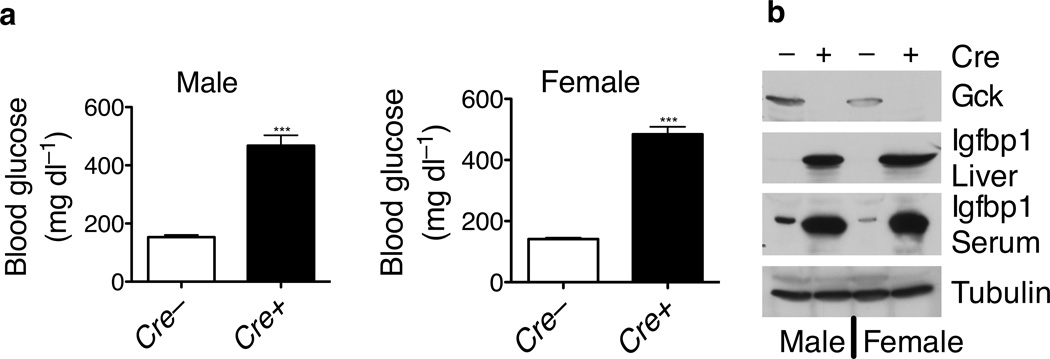

Liver–specific deletion of Akt1 in Akt2 null mice results in hyperglycemia

In mouse liver, Akt2 accounts for 84% of total Akt protein, the remainder being Akt1 with Akt3 not detectable35. Whole body Akt2 null mice (Akt2−/−) display a mildly diabetic phenotype on a mixed 129–C57BL/6J background4. A plausible explanation for the relative mildness of the glucose intolerance is that residual Akt1 in liver of the Akt2−/− mice partially rescued insulin responsiveness. To address this question, we bred Akt1loxP/loxP;Akt2−/− mice to Afp–Cre mice, which express Cre recombinase specifically in liver36, to generate mice with systemic Akt2 and liver–specific Akt1 deletion. Akt1 deletion in liver of Akt2−/− mice led to severe hyperglycemia, whether compared to wildtype or Akt2−/− mice (Fig. 1a). In addition, these mice lacked Gck protein in liver, and had increased Igfbp1 protein both in liver and in serum (Fig. 1b). Since Igfbp1 is a major target gene for Foxo16, these data suggested Foxo1 activation in these livers.

Figure 1. Liver–specific deletion of Akt1 in the Akt2 whole body knockout mice resulted in severe hyperglycemia and disruption of Foxo1–regulated gene expression.

(a) Fed blood glucose in the Akt2−/−;Akt1loxP/loxP mice in the presence (Cre+) or absence (Cre−) of Afp–Cre (*** P < 0.001, n = 7, 8). (b) Western blot for Gck in liver lysates, and Igfbp1 in both liver lysates and serum.

Insulin signaling defects in the liver–specific Akt1, Akt2 double knockout mice

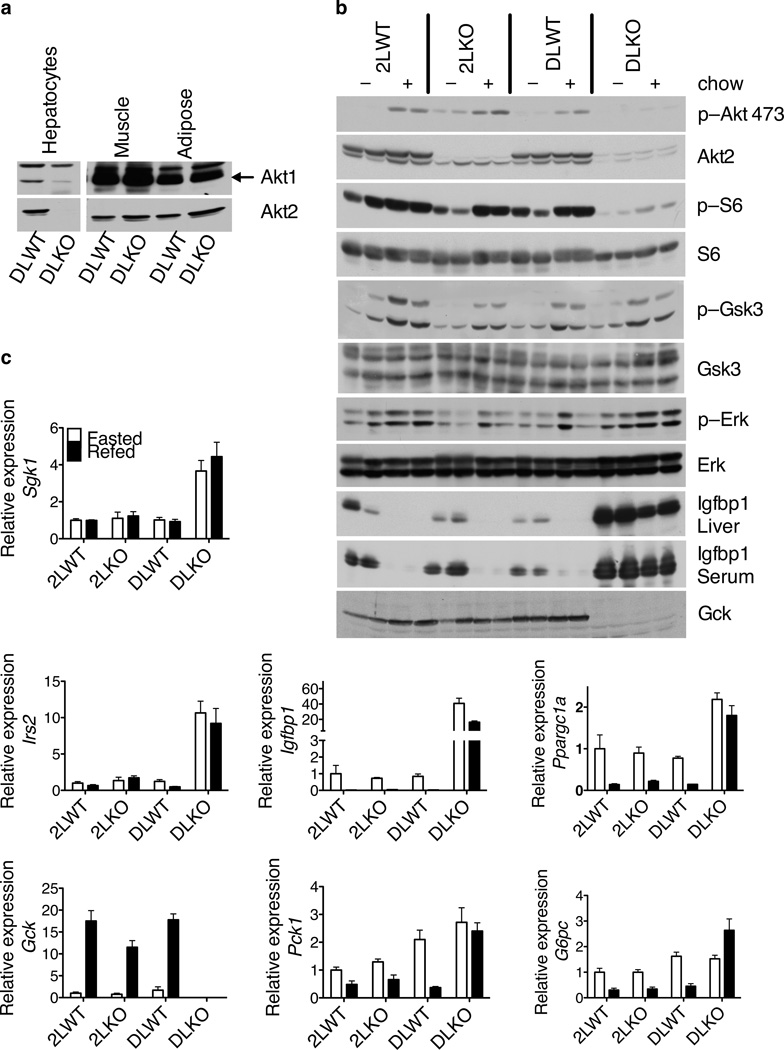

To understand in more detail the hepatic functions of Akt kinases without the complications of peripheral insulin resistance4, we injected Akt2loxP/loxP mice and Akt1loxP/loxP;Akt2loxP/loxP mice with adeno–associated virus expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the Tbg promoter (AAV–Tbg–Cre), which led to the liver–specific deletion of Akt2 alone (2LKO) and both Akt1 and Akt2 (DLKO), respectively (Fig. 2a, b). Akt2loxP/loxP mice (2LWT) and Akt1loxP/loxP;Akt2loxP/loxP mice (DLWT) injected with virus expressing GFP served as controls. Expression of GFP or Cre in wildtype livers using this viral delivery system did not result in any detectable change in carbohydrate or lipid metabolism (data not shown).

Figure 2. Aberrant insulin signaling and disrupted expression of Foxo1–regulated genes in the DLKO livers but not in the 2LKO livers.

(a) Western blot of Akt1 and Akt2 in primary hepatocytes, muscle and adipose tissues from the DLWT and DLKO mice. (b) Western blot of liver lysates. p–Akt 473: phosphorylation of Akt at S473. p–S6: phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 at S240, S244. p–Gsk3: phosphorylation of Gsk3α at S21 and Gsk3β at S9. p–Erk: phosphorylation of Erk at T202 and Y204. (c) Relative expression of genes in livers quantitated by real time PCR. In (b) and (c), mice were either fasted overnight (open bars) or fasted overnight followed by 4 hours feeding with normal chow (filled bars).

Western blot confirmed efficient deletion of Akt1 and Akt2 in hepatocytes from the DLKO mice 2 weeks after virus injection (Fig. 2a). There was no change in Akt1 or Akt2 protein in muscle or adipose tissue. To investigate the effect of removing Akt kinases on hepatic insulin signaling, we fasted the mice overnight and then fed the mice with normal chow. In comparison to the 2LWT control mice, indices of insulin–dependent signaling, such as phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6, phosphorylation of Gsk3α and Gsk3β, and decrease in Igfbp1 protein, remained relatively unchanged in 2LKO livers after feeding (Fig. 2b). In spite of Akt2 contributing the majority of Akt protein in liver, postprandial phosphorylation of Akt at S473 was unchanged in 2LKO livers. This is likely a reflection of the low stoichiometry of Akt phosphorylation in the prandial state and the ability of Akt1 to compensate for deficiency in Akt2. To test this possibility, we injected a supraphysiological dose of insulin into the 2LWT and 2LKO mice. 20 minutes after insulin injection, Akt phosphorylation at S473 was notably lower in the 2LKO livers compared to the control livers (Supplementary Fig. 1). These data indicate that chow feeding led to phosphorylation of only a small fraction (< 4%) of the endogenous Akt.

In the DLKO livers, the feeding–induced phosphorylation of Akt at S473 was decreased to virtually undetectable levels (Fig. 2b). S6 phosphorylation was diminished but phosphorylation of Gsk3α and Gsk3β was preserved. The normal phosphorylation of Gsk3α and Gsk3β likely reflected higher expression in the DLKO livers of serum–glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 (Sgk1) (Fig. 2c), which is known to phosphorylate Gsk3α and Gsk3β in response to insulin37. Erk2 kinases, which are downstream of insulin receptor in a pathway parallel to Akt, were activated normally in the DLKO livers after feeding (Fig. 2b).

Disrupted expression of the Foxo1–regulated genes in the DLKO livers

The Foxo1 transcription factor represents a major target of Akt. Expression of Irs2, a direct Foxo1 target gene6, was significantly higher in the DLKO compared to the control livers (Fig. 2c). Other Foxo1–dependent genes, such as Ppargc1a and Igfbp138–40, were also induced in the DLKO livers (Fig. 2c). The expression of Gck, a Foxo1–suppressed gene6,27,41, was markedly lower in the DLKO livers compared to the control livers. Expression of G6pc and Pck1 in the DLKO livers was not different from the control livers during fasting, but the normal suppression of these genes after feeding was lost in the DLKO livers (Fig. 2c). Consistent with altered gene expression, Igfbp1 protein was substantially more abundant in both liver and serum upon deletion of both Akt1 and Akt2 from liver, and Gck protein was almost undetectable (Fig. 2b). Taken together, these data indicate strongly that activation of Foxo1 is an important consequence of deleting all Akt from the liver.

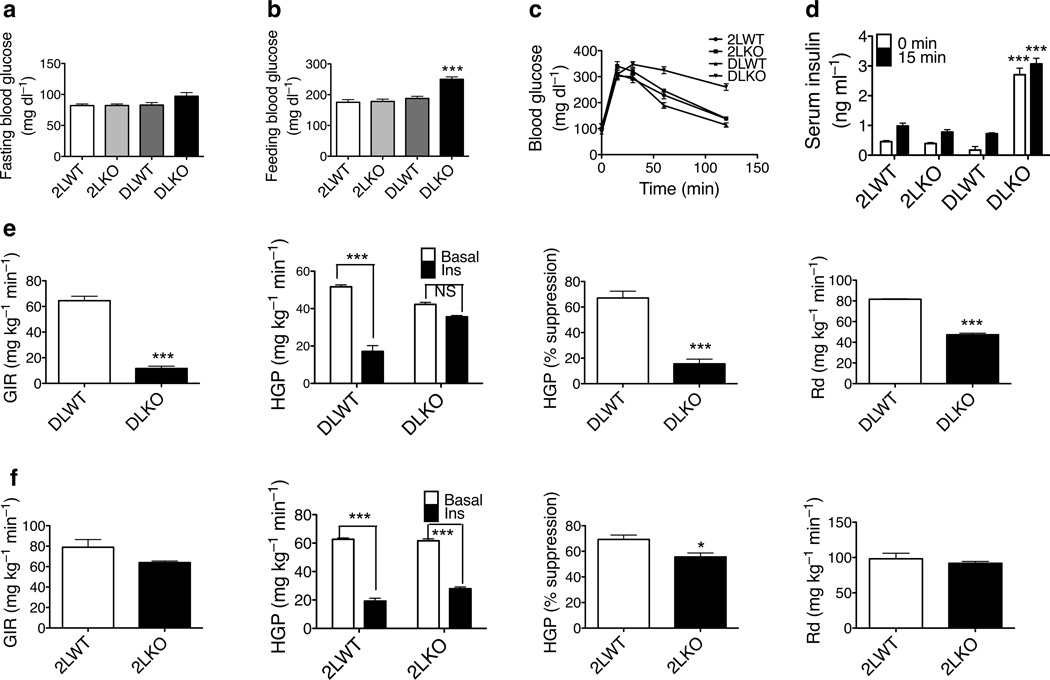

Hyperglycemia, glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in the DLKO mice

2 weeks after virus injection, the fasting blood glucose concentration in the DLKO mice trended to be higher than the control mice but the difference did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3a). However, the blood glucose concentration after overnight fast and 4 hours feeding was significantly higher in these mice (Fig. 3b). Glycogen content was considerably lower in the DLKO livers 4 hours after feeding (Supplementary Fig. 2). 3 weeks after virus injection, blood glucose concentrations in the DLKO mice during both fasting and refeeding were higher than in control mice (not shown). To minimize the potential secondary effects resulting from hyperglycemia, subsequent experiments were performed 2 weeks after virus injection.

Figure 3. Deletion of both Akt1 and Akt2 in livers results in hyperglycemia, glucose intolerance and insulin resistance.

Blood glucose in mice after overnight fast (a) and 4 hours feeding (b). (*** P < 0.001, n = 7, 8). (c) Oral glucose tolerance test. (d) Serum insulin before and fifteen minutes after glucose gavage. (e) Hyperinsulinemic–euglycemic clamp in the DLWT and DLKO mice. (f) Hyperinsulinemic–euglycemic clamp in the 2LWT and 2LKO mice. GIR: glucose infusion rate; HGP: hepatic glucose production; Rd: rate of glucose disposal. (* P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001, NS: not significant, n = 4, 5)

When challenged with glucose, the DLKO mice were glucose intolerant (Fig. 3c). Serum insulin concentration during both fasting and the glucose tolerance test were higher than the control mice (Fig. 3d), suggesting insulin resistance in these mice. This was confirmed by a hyperinsulinemic–euglycemic clamp (Fig. 3e), which revealed a much lower glucose infusion rate and failure to suppress liver glucose output by insulin in the DLKO mice. Glucose disposal rate in the DLKO mice was also lower than in the control mice (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 3), indicating that these mice developed peripheral insulin resistance as a result of removal of Akt1 and Akt2 in liver. In most of these assays, 2LKO mice were indistinguishable from control mice, though there was a small but significant blunting of postprandial glycogen storage (Supplementary Fig. 2) and insulin–dependent suppression of hepatic glucose output (Fig. 3f).

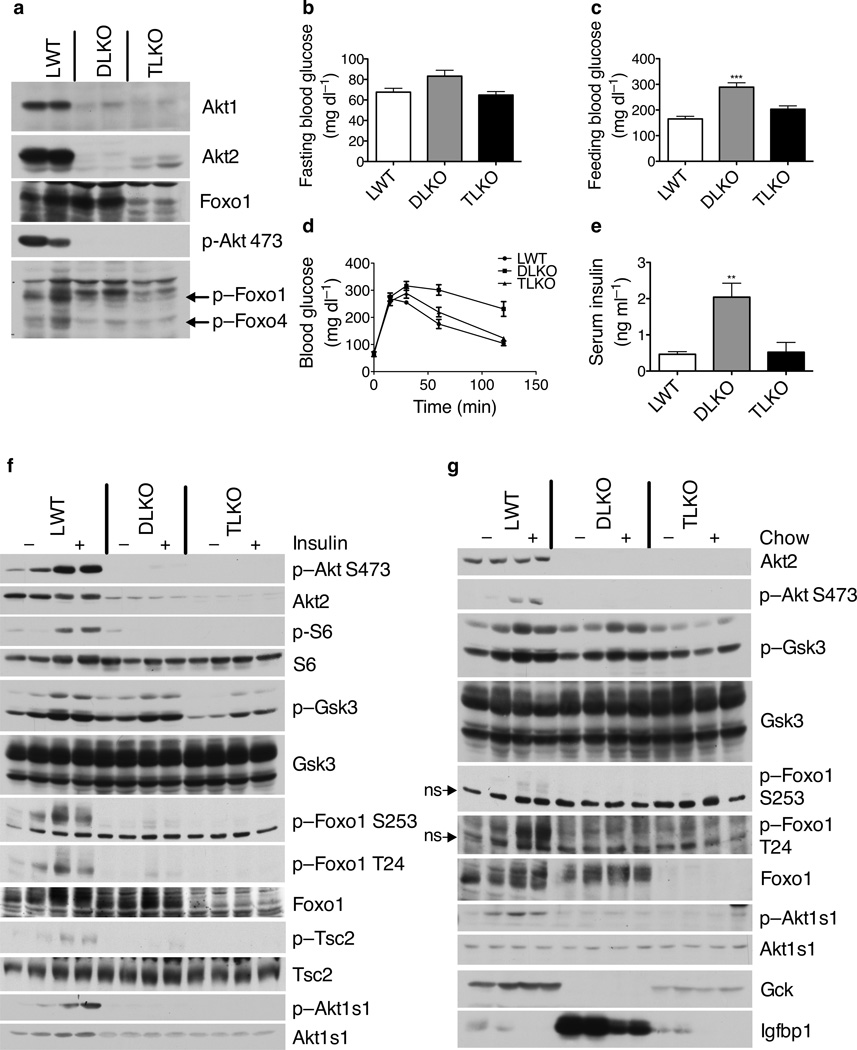

Effects of liver–specific Foxo1 deletion from wildtype and DLKO mice

Since Akt suppresses Foxo1 activity, if activation of Foxo1 were responsible for the glucose intolerance and altered gene expression in DLKO mice, deletion of Foxo1 should largely reverse the abnormal metabolism. Mice with liver–specific chronic deletion of Foxo1 developed hypoglycemia after prolonged fasting31,32. To assess the effect of acute removal of Foxo1 from liver, we injected the Foxo1loxP/loxP mice31 with AAV–Tbg–Cre. Efficient deletion of Foxo1 was confirmed by the decrease in both mRNA and protein (Supplementary Fig. 4a and 4b). These mice displayed hypoglycemia after overnight fasting but euglycemia after feeding (Supplementary Fig. 4c and 4d). To investigate whether unrestrained activation of Foxo1 in the DLKO livers was indeed responsible for the metabolic disturbances in the DLKO mice, we deleted Foxo1 from the DLKO livers. Injection of AAV–Tbg–Cre into Akt1loxP/loxP;Akt2loxP/loxP;Foxo1loxP/loxP mice resulted in the liver–specific recombination of all three genes (TLKO), as confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 4a). Mice injected with virus expressing GFP instead of Cre served as controls (LWT). In the TLKO mice, fasting blood glucose concentration was indistinguishable from that in control mice (Fig. 4b). Hyperglycemia present 4 hours after feeding in the DLKO mice was normalized in the TLKO mice (Fig. 4c). Deletion of Foxo1 also reversed the glucose intolerance and fasting hyperinsulinemia in the DLKO mice (Fig. 4d, 4e). In contrast, liver glycogen 4 hours after feeding remained lower in the TLKO livers than the control livers (Supplementary Fig. 5), despite Foxo1 deletion normalizing the suppressed glucose ↔ glucose–6–phosphate cycling in the DLKO livers (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Figure 4. Deletion of Foxo1 normalizes hyperglycemia, glucose intolerance, and hyperinsulinemia in DLKO livers despite defective insulin signaling.

(a) Western blot of the lysates from primary hepatocytes isolated from fed mice. The phospho–specific antibody detected phosphorylation of Foxo1 at T24 and Foxo4 at T28. (b) Blood glucose after overnight fast. (c) Blood glucose after overnight fast followed by 4 hours feeding. (*** P < 0.001, n = 9) (d) Oral glucose tolerance test. (e) Fasting serum insulin. (** P < 0.01, n = 5). (f) Western blot of liver lysates from mice fasted overnight and injected with either insulin or saline. (g) Western blot of liver lysates from mice fasted overnight or fasted overnight followed by 4 hours feeding with normal chow (ns: non–specific band).

In hepatocytes from both DLKO and TLKO mice, phosphorylation of Akt at S473, Foxo1 at T24, Foxo4 at T28 was not detectable (Fig. 4a). In control fasted mice, insulin injection quickly induced robust phosphorylation of Akt, S6, and direct Akt substrates such as Foxo1, Tsc242, and Akt1s1 (also known as Pras40)43 in liver (Fig. 4f). These phosphorylation events were either lost or markedly blunted in both the DLKO livers and the TLKO livers. In line with these observations, no compensatory increase in Akt3 was detected in either the DLKO livers or the TLKO livers (Supplementary Fig. 7). Phosphorylation of Gsk3α and Gsk3β was maintained in both DLKO livers and TLKO liver, though to lesser extent in the latter (Fig. 4f).

Similar to insulin injection, feeding elicited enhanced phosphorylation of Akt at S473, Foxo1 at S253 and T24, and Akt1s1 in the control livers, but not in the DLKO or TLKO livers (Fig. 4g). Gsk3α and Gsk3β phosphorylation was induced after feeding in the DLKO liver but not in the TLKO livers, correlating with the increase of Sgk1 in the DLKO livers and its normalization in the TLKO livers (Supplementary Fig. 8). In the TLKO livers, Gck protein levels were partially normalized, and Igfbp1 protein was restored to the same level as in the control mice (Fig. 4g), consistent with Foxo1 activity being considerably higher in the DLKO livers than the control or TLKO livers.

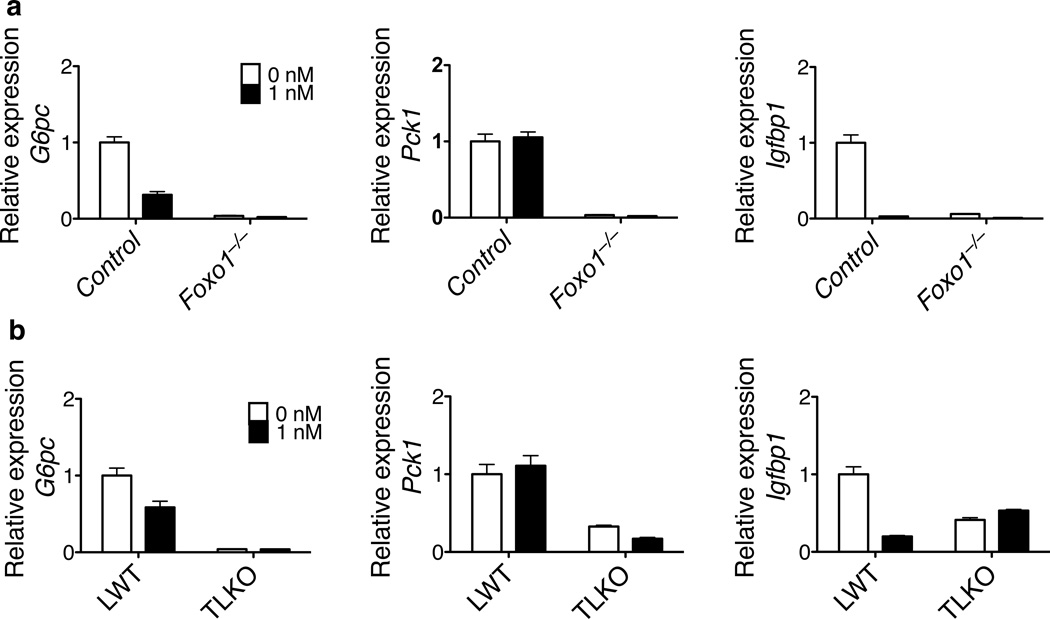

Normal response to feeding and insulin in livers lacking both Akt and Foxo1

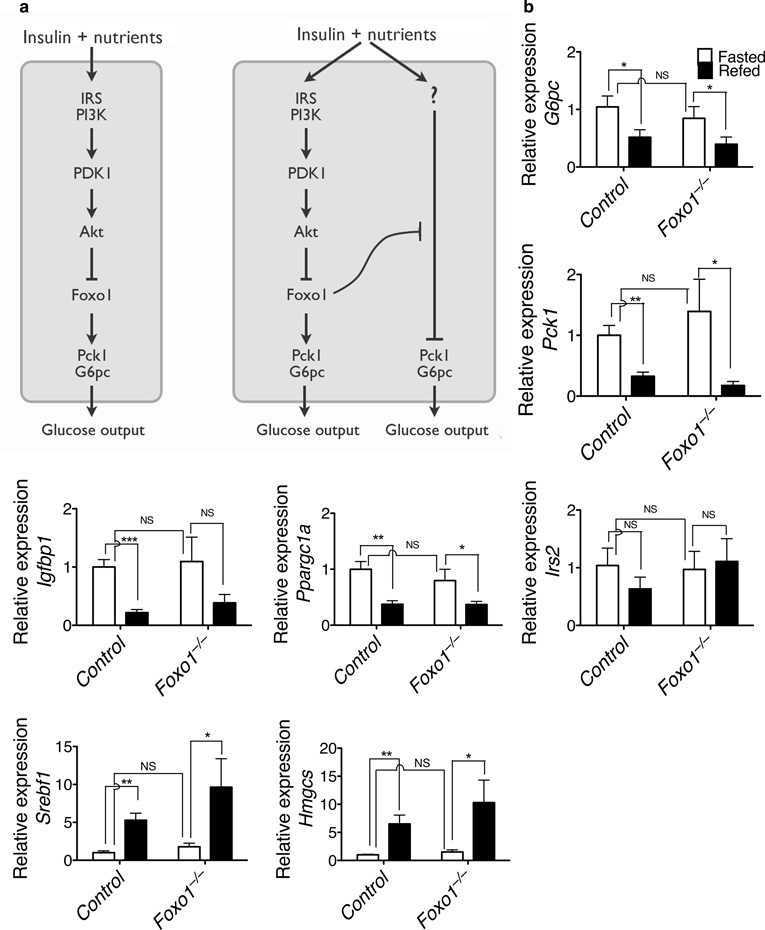

The above data are consistent with the prevailing view that Akt drives adaptation to the fed state by suppressing Foxo1–dependent gene expression, such that defects resulting from ablation of Akt signaling are reversed by concomitant removal of Foxo1 (Fig. 4). Analogous data have been interpreted as reflecting a linear pathway in which Foxo1 promotes transcription of those genes encoding rate–determining gluconeogenic enzymes. However, a plausible alternative view that is compatible with both published and our new data is that Foxo1 also represses a parallel, Akt–independent signaling pathway that controls the prandial response (Fig. 5a). To distinguish between these models, expression of critical metabolic genes was measured in the fasted state and after feeding. If the canonical view is correct, deletion of Foxo1 alone or deletion of both Akt and Foxo1 should “lock” gene expression into the fed state, mimicking the continual presence of insulin. However, if insulin–dependent inhibition of Foxo1 serves primarily a permissive function, then deletion of Foxo1 alone or deletion of both Akt and Foxo1 would restore normal postprandial regulation. Acute deletion of Foxo1 from liver did not significantly alter the expression of G6pc, Pck1 and Igfbp1 during fasting or after feeding, and the fasting to feeding transition was largely normal (Fig. 5b). As shown in Figure 5c, in control animals feeding induced the expected regulation of gene expression, as indicated by decreases in Ppargc1a, Igfbp1, Pck1, and G6pc, and increases in Srebf1, HMG-CoA reductase (Hmgcr), HMG-CoA synthase (Hmgcs) and Gck. In the DLKO livers, the expression of these genes under the fasted and the fed state resembled that of the fasted state in the control livers, though Ppargc1a, Igfbp1, Srebf1, and Hmgcr continued to be regulated to some extent by feeding. Of note, for most genes tested, the TLKO livers responded to feeding in a manner indistinguishable from control livers, indicating that their regulation in these livers was through a mechanism independent Akt and Foxo1. These data support a permissive role for Akt–mediated suppression of Foxo1 rather than or in addition to Akt acting as an obligate intermediate in the postprandial signaling pathway.

Figure 5. Nutritional regulation of hepatic gene expression in the absence of Foxo1 alone and in the absence of both Akt and Foxo1.

(a) Two alternative models for signaling by Akt in liver. On the left is the traditional view, in which there is a linear pathway terminating at the control of gluconeogenic gene expression. On the right is a newly proposed model, in which Akt constitutively suppresses Foxo1, which is a global inhibitor of the metabolic transition in liver that accompanies food intake. (b) Hepatic gene expression in the control mice and the acute, liver–specific Foxo1 knockout mice. (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, NS, not significant, n = 8). (c) Hepatic gene expression in LWT, DLKO and TLKO mice. (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, NS, not significant, n = 7, 8). (d) Relative expression of G6pc and Pck1 under euglycemic clamp condition (** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, n = 6). (e) Hyperinsulinemic–euglycemic clamp (*** P < 0.001, NS, not significant, n = 4, 5).

In order to assess the scope of Foxo1’s effects on expression of metabolically responsive genes, mRNA from LWT, DLKO and TLKO livers were subjected to genome–wide expression analysis. 688 genes were classifies as “metabolically responsive”, as defined by having at least 2–fold change from fasting to feeding in control livers (Supplementary Table 1). Of these, 298 genes showed altered expression in the DLKO livers compared to control livers four hours after feeding (Supplementary Table 2), indicating that Akt was critical to their regulation. As shown in the “heatmap” in Supplementary Figure 9, for most members of the 298 metabolically regulated genes, their expression in the DLKO livers in both fasted and fed state behaved like the fasted state in control livers (compare columns 3 and 4 to column 1) and the dysregulated gene expression was largely reversed in the TLKO livers (compare columns 1, 2 to columns 5, 6). Whether expression was induced or suppressed in the control livers after feeding, the disruption in regulation in the DLKO livers was at least partially reversed in the TLKO livers, reestablishing appropriate postprandial adaptation. Given that an analogous experiment has been performed with liver–specific Irs1;Irs2 double knockout mice6, we compared the ratio of gene expression in mutant to wildtype mice for liver–specific Irs1;Irs26 and Akt1;Akt2 knockout mice in the fasted and fed states (Supplementary Fig. 10). As predicted, there was a striking concurrence between the changes resulting form deletion of the two Irs genes and the two Akt genes in liver. The largely appropriate switch in gene expression from the fasted to fed state in the TLKO and the Irs1;Irs2;Foxo1 triple knockout livers demonstrates that livers lacking Foxo1 and much of the proximal insulin signaling pathway are capable of mounting a normal transcriptional response to nutritional intake.

The restoration of normal regulation in TLKO liver raised two important questions: 1) does the appropriate postprandial response in livers null for Akt and Foxo1 reflect a reestablishment of insulin action? and 2) are the changes in gene expression in TLKO mice accompanied by a corresponding suppression of hepatic glucose output? To dissociate the effects of insulin and nutrients on gene expression, mRNA encoding key regulatory proteins was measured in control and TLKO livers during euglycemic clamp with and without infusion of insulin. As shown in Figure 5d, expression of G6pc and Pck1 was suppressed by insulin to the same extent in the TLKO livers as in the control livers, indicating that insulin was able to suppress the transcription of these two genes independent of Akt and Foxo1 in liver. Notably, insulin also suppressed glucose production in the TLKO mice in a manner that was indistinguishable from the control mice, as ascertained by euglycemic clamp (Fig. 5e). These data further support the permissive role for Akt–dependent inhibition of Foxo1, as normal regulation persists in the absence of both proteins.

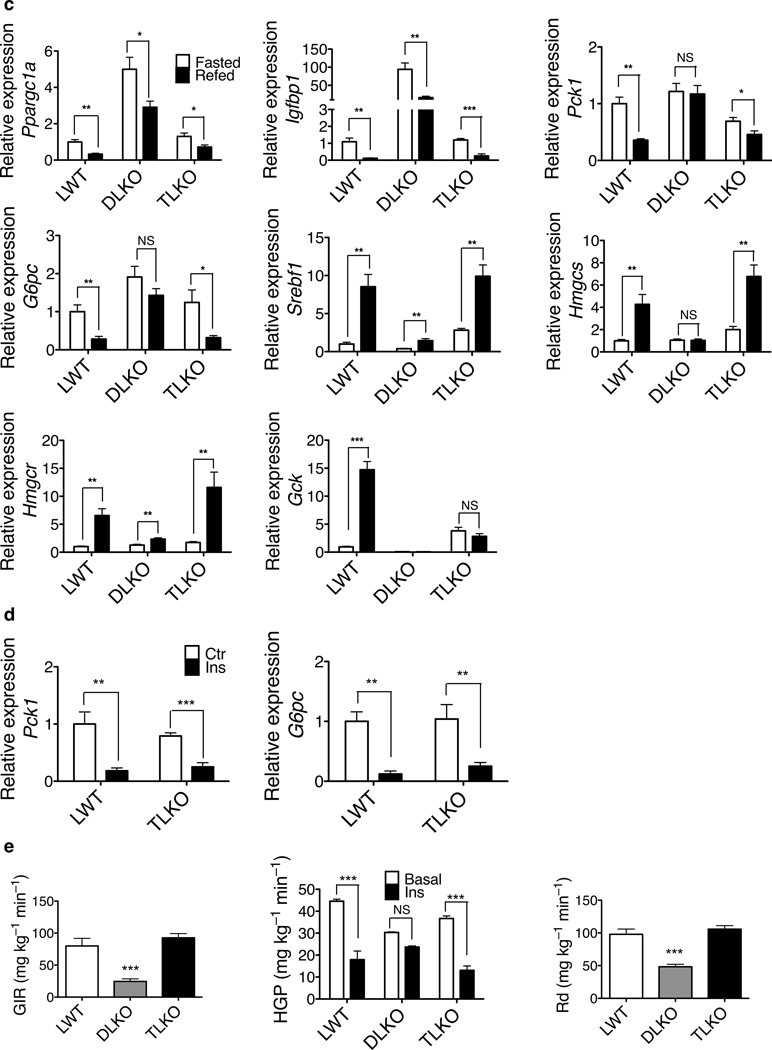

The data presented above indicated that Foxo1 exerts a suppressive effect on postprandial insulin–responsive pathway that signals independent of Akt. To ask whether this alternative pathway is the sole mediator of insulin action or exists in parallel to the canonical pathway, hepatocytes were isolated from the TLKO livers and tested for their response to insulin in vitro. As a comparison, hepatocytes from the Foxo1−/− livers were also tested. As shown in Figure 6, in both Foxo1−/− and TLKO primary hepatocytes, the expression of G6pc, Pck1 and Igfbp1 was substantially lower than in control cells and did not respond to addition of hormone. Thus, when studied ex vivo, liver cells behaved as if insulin signals through the canonical linear pathway of Akt–dependent inhibition of Foxo1–driven gluconeogenic gene expression (Figure 5a).

Figure 6. Insulin–regulated expression of Foxo1 targets genes was compromised in the Foxo1−/− and TLKO primary hepatocytes.

Primary hepatocytes were isolated from control and Foxo1−/− livers (a), or LWT and TLKO livers (b). The hepatocytes were cultured overnight in 1 nM insulin–containing medium and additional 6 hours in the presence or absence of 1 nM insulin. Relative expression of the listed genes was quantitated by real time PCR.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we used genetic manipulation of the mouse genome to study the tissue–specific, physiological functions of Akt and Foxo1 in insulin–regulated metabolic responses in liver. We established that hepatic Akt is essential in maintaining whole body glucose homeostasis and insulin responsiveness, and that Akt kinases execute these functions primarily through suppressing Foxo1. However, we also made several unexpected observations that cannot be explained by the prevalent, long–held model in which insulin regulates glycemia via Akt–dependent suppression of Foxo1–driven metabolic gene expression. First, and most surprisingly, feeding, and to a significant extent insulin alone, suppresses hepatic glucose output and appropriately regulates gene expression in the absence of Akt and Foxo1, indicating that the former is not an obligate intermediate in insulin’s actions to control liver metabolism under some conditions in vivo. This conclusion necessitates a significant reevaluation of the current view of how insulin utilizes Akt as a “downstream” signaling molecule in liver44. Second, Foxo1 is activated under both fasting and feeding conditions upon loss of Akt in liver, indicating that there is sufficient Akt signaling during fasting to repress a substantial portion of Foxo1 activity towards many genes. The functional consequences of this is illustrated by the rather small decreases in blood glucose when Foxo1 is deleted from wildtype liver, but the greater metabolic changes when excised from an Akt–deficient liver (Fig. 4, 5 and Supplementary Fig. 4).

Though about 84% of the Akt protein in liver is represented by the Akt2 isoform, 2LKO mice are almost indistinguishable from control mice in these studies (Fig. 2 and 3). In contrast, in a previous publication we reported protection from steatosis in mice with liver–specific deletion of Akt2 and wildtype levels of Akt145. However, there are two critical differences in the design of those experiments compared to the current study: 1) in the previous study, the metabolic assays focused on lipid synthesis and accumulation and 2) the role of liver Akt2 was ascertained in obese, insulin–resistant mice. In contrast, when fed with normal chow, insulin dependent signaling and glucose tolerance are largely wildtype in 2LKO mice, indicating the capacity of residual Akt1 to compensate under these conditions. Consistent with this idea, 4 hours postprandial Akt phosphorylation is nearly the same in control and 2LKO livers (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating that only a small fraction of total hepatic Akt is phosphorylated after normal chow feeding, but this is largely sufficient to convey insulin’s signal. In contrast to 2LKO mice, DLKO mice are hyperglycemic, glucose intolerant and insulin resistant (Fig. 3 and 4). These phenotypes are similar to those produced by liver–specific insulin receptor knockout (LIRKO)5 and liver–specific Irs1 and Irs2 double knockout6. Hyperglycemia in the DLKO mice is milder than that in the other two insulin signaling deficient models, though this might have been due to acute deletion of Akt1 and Akt2 from the livers of DLKO mice, rather than Cre–dependent recombination early in life, which would enhance the development of secondary peripheral insulin resistance. The similar phenotypes between the Irs1, Irs2 liver–specific double knockout mice and the DLKO mice suggest that the signaling is linear between these two nodes without major branch points.

In TLKO livers, despite the lack of Akt and Foxo1 the liver adapts appropriately to the fed state, successfully modulating its gene expression and maintaining euglycemia (Fig. 4, 5). The appropriate regulation in these mice indicates that there is a pathway independent of Akt and Foxo1 that signals the liver’s adaptation to feeding. This parallel pathway may have been partially functional even in the DLKO livers, as expression of some genes, such as Ppargc1a, Igfbp1, Srebf1 responds to feeding; however, many more lose regulation in DLKO only to regain in the TLKO livers. Perhaps most notably, in TLKO mice insulin suppresses hepatic glucose production in a manner indistinguishable from that in control mice (Fig. 5e). These results demonstrate clearly that Akt is not required for insulin to regulate hepatic metabolism under all conditions and thus the kinase does not represent an obligate intermediate only in a simple, linear pathway. However, the disrupted glucose metabolism and significant insulin resistance in the DLKO livers indicate that under normal conditions Akt is indispensable to the preservation of metabolic homeostasis. Furthermore, normalization of the metabolic disturbances in the DLKO liver by additional deletion of Foxo1 argues that the predominant role of Akt is to suppress Foxo1. To reconcile these seemingly conflicting data, we propose that active Foxo1 exerts a general repressive effect on many of the early physiological adaptations to feeding (Supplementary Fig. 11). We suggest that Akt participates in the liver’s response to postprandial insulin and nutrient abundance by maintaining the suppression of Foxo1 activity, thus allowing the full prandial response. Importantly, even during the fasting state, a repressive function of Akt towards Foxo1 is still largely operational, such that the changes in Foxo1 activity that accompany normal physiological fluctuations in insulin levels are rather modest. We propose that Akt maintains a persistent suppressive effect on a large fraction of Foxo1 throughout routine daily periods of fasting and feeding. Though this interpretation represents a departure from the traditional model of insulin action, it is nonetheless consistent with the substantial body of relevant published data as well as the results presented herein. As discussed above, expression of Foxo1 target genes in response to change in metabolic states can occur in the absence of Akt and Foxo1 (Fig. 5). Moreover, there appear to be striking differences in the impact of Foxo1 deletion in normal versus insulin–resistant livers. In mice not stressed by insulin resistance, acute deletion of Foxo1 does not significantly reduce the expression of Foxo1 target genes (Fig. 5b), although chronic deletion of multiple Foxo family members including Foxo1 results in modest reduction of expression of these genes31,32. In contrast, in this and previous reports6,31, the effects of Foxo1 deletion on the expression of these genes are more dramatic in mice with insulin resistance, whether induced genetically or by nutritional overabundance, and the scope of Foxo1 deletion is broader, affecting not only the gluconeogenic but many anabolic programs as well (Supplementary Fig. 9). In fact, many of the studies that have supported a major role for Foxo1 in the control of glucose homeostasis are performed in mouse models of insulin resistance23,33,34, or by overexpressing a gain–of–function Foxo1 mutant28. Even in model organisms such as Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster, the functional importance of Foxo orthologs is best revealed on genetic backgrounds with defective insulin signaling46–48. These data are compatible with the idea that Foxo1 becomes active during insulin resistance but is largely repressed in normal mice.

At present, it is unclear how Akt exerts a repressive effect on Foxo1 during fasting. The established mechanism by which Akt directly inhibits Foxo1 involves its phosphorylation at T24, S253 and S316 of the mouse protein by Akt. Both feeding and insulin injection into the fasted mice induced Foxo1 phosphorylation at these sites, indicating that the majority of Foxo1 is not phosphorylated during fasting and therefore cannot be used to explain the Akt–dependent repression of Foxo1. Foxo1 is phosphorylated at sites in addition to those mentioned above, and its activity is modulated through acetylation39, methylation49, glycosylation50 and ubiquitination51. It remains to be determined if Akt affects Foxo1 activity through these modifications, or via a cofactor that functions cooperatively with Foxo152.

One trivial possibility that could be raised to explain the lack of major effect of deletion of Foxo1 on fasting metabolism is functional rescue by other Foxo family members. This is unlikely for several reasons. First, there is little enhancement of fasting hypoglycemia in liver–specific Foxo1 null mice when additional family members are deleted32. Second, if Foxo family members other than Foxo1 were capable of transmitting a signal to gluconeogenic gene expression and enhanced hepatic glucose output, then deletion of Foxo1 alone would be unable to suppress the abnormalities incurred by removal of Akt1 and Akt2 from liver. In this study we found a more profound effect of deletion of Foxo1 alone in the liver on fasting glycemia than has been reported previously31, possibly due to the acute nature of the recombination in our protocol. Of note, the hypoglycemia in the liver–specific Foxo1 knockout is reversed by concomitant deletion of Akt (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4). These data suggest that the phenotypes in the liver–specific Foxo1 deletion mice depend on the presence of functional Akt, though the underlying mechanism is not clear.

A major question to be addressed in future studies is the nature of the regulatory signal(s) triggered by feeding that are suppressed by the unrestrained activity of Foxo1 (Supplementary Fig. 11). Since mice with liver–specific knockout of Irs1 and Irs2 display a pattern of gene expression similar to DLKO mice6, including suppression by concomitant deletion of Foxo1, it is likely that any Akt–independent, cell–autonomous pathway for control of hepatic metabolism is also not signaled through the Irs proteins. In addition, the loss of phosphorylation of recognized Akt substrates in the DLKO as well TLKO livers argues strongly against the idea that Akt–like kinases are rescuing insulin signaling under these conditions (Fig. 4f, 4g). These data are consistent with the absolute requirement for Foxo1 for insulin regulation of gene expression in primary hepatocytes, results that contrast sharply with the relatively normal insulin action in vivo. Taken together, these data suggest strongly that insulin’s regulation of hepatic function in the TLKO mice is cell non–autonomous, i.e. the direct insulin target organ is not liver. Moreover, as shown in Figure 6, hepatocytes studied ex vivo behave like cells that utilize a linear pathway in which Akt suppresses Foxo1–dependent gene expression. Thus it is likely that the canonical Akt–Foxo pathway operates in a cell autonomous manner in response to insulin, while there is a parallel pathway in which insulin signals to liver through another intermediary tissue. Consistent with the idea of cell non–autonomous regulation of hepatic metabolism, restoration of hepatic insulin signaling alone is not sufficient to reverse the diabetic phenotype associated with systemic loss of insulin receptor53. One candidate target organ for insulin is the central nervous system, as a number of studies have provided data supporting a role of insulin signaling through brain to control hepatic glucose output53–57. It will be of great interest to determine conclusively if the apparent normal suppression of liver glucose production in the TLKO livers is mediated through insulin signaling in liver or at some other sites, such as brain or adipocytes.

These findings have implications for understanding the pathophysiology of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and potentially designing effective therapeutics. Given the substantial evidence cited above that Foxo1 is inappropriately active in rodent models of insulin resistance, the idea has emerged that, like Type 1 diabetes mellitus, T2DM resembles a physiological fasting state during periods of nutritional abundance. However, the data presented herein reveal that Foxo1 is largely inactive in healthy animals and thus the metabolic state of liver in T2DM represents a true pathological condition. Moreover, we predict that adequate suppression of Foxo1 through targeted therapeutics would restore much of the normal regulation in individuals with T2DM. This strategy has advantages over the current treatments that produce a state mimicking constitutive hyperinsulinemia with all of the attendant adverse consequences such as increased lipid synthesis and hyperlipidemia. Lastly, but perhaps most importantly, the demonstration of an insulin–dependent, Akt–independent pathway for suppressing liver glucose output raises the possibility of novel targets for the treatment of hyperglycemia.

METHODS

Mice

We used male mice in all the experiments, except for those as indicated. The Akt1loxP/loxP mice58, Akt2−/− mice4, Akt2loxP/loxP mice45, Foxo1loxP/loxP mice31 were described previously. We backcrossed the Akt2−/− mice, Akt1loxP/loxP mice, Akt2loxP/loxP mice onto C57/BL6J background and further intercrossed these mice to generate the desired genotypes. We generated The Akt1loxP/loxP;Akt2loxP/loxP;Foxo1loxP/loxP mice by crossing the Akt1loxP/loxP;Akt2loxP/loxP mice with the Foxo1loxP/loxP mice. These mice were on the 129–C57BL–6J/FVB mixed background. We recovered the Akt1loxP/loxP;Akt2loxP/loxP mice on the same background and used them to compare the DLKO against TLKO. For fasting–refeeding experiments, we fasted mice 16 hours (4 PM to 9 AM), then sacrificed the mice (for fasted groups), or refed the mice with normal chow (Laboratory Rodent Diet, Cat. 5001. Percentage calories provided by protein: 29%, by Fat: 13%, by carbohydrates: 58%) for additional 4 hours before sacrifice (for refed group). For insulin injection, we fasted the mice for 16 hours, injected the mice with either phosphate buffered saline or insulin at 2 mU g−1 body weight and waited for 20 minutes before sacrificing the mice and freeze clamping the livers. All mice experiments were reviewed and approved by the University of Pennsylvania IACUC in accordance with NIH guidelines.

Adeno–associated virus injection

We injected 6 to 8 weeks old mice with adeno–associated virus at 1011 genomic copies per mouse. Experiments were performed 2 weeks after virus injection.

Liver lysates extraction and Western blotting

We freeze–clamped and stored livers at −80 °C until the time of further processing. We extracted lysates from frozen livers with RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 1% Triton X–100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors). We used the cleared lysates for Western blot. We used the following antibodies: antibody to Akt2 was described previously59; antibodies to Akt1, phospho–Akt S473, phospho–S6 (S240/S244), S6, Foxo1, phospho–Foxo1 T24, phospho–Foxo1 S253, phospho–Gsk3 (S21/S9), phospho–Erk (T202/Y204) were from Cell Signaling Technology; antibodies to Gsk3, Igfbp1, Erk were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; antibody to Gck was kindly provided by Mark A. Magnuson (Vanderbilt University).

Primary hepatocytes isolation and culture

We isolated primary hepatocytes as previously described60. We cultured the cells in M199 medium containing 100 nM T3, 100 nM dexamethasone and 1 nM insulin overnight. For gene expression analysis, we cultured the cells for additional 6 hours in the same medium with or without 1 nM insulin.

mRNA Isolation and real time PCR

We isolated total RNA from the frozen livers or primary hepatocytes using the RNeasy Plus kit from Qiagen. We synthesized cDNA using M–MLV reverse transcriptase, and quantitated the relative expression of genes of interest by real time PCR using the SYBR Green Dye–based assay.

Glucose tolerance test

We fasted the mice overnight, gave them glucose at 1 g kg−1 body weight by oral gavage. We monitored glucose by tail bleeding at 0, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes after glucose injection. We measured insulin concentration in serum collected before and 15 minutes after glucose gavage.

Liver glycogen content measurement

We fasted mice overnight. We then sacrificed the mice (fasted mice), or fed the mice for 4 hours before sacrificing (fed mice). We extracted liver glycogen with 6% cold perchloric acid, which was then neutralized with potassium hydroxide. We treated glycogen in the supernatant with amyloglucosidase. We then measured glucose content before and after the amyloglucosidase treatment, and we calculated the difference as the glycogen content.

Hyperginsulinemic–euglycemic clamp

We performed the hyperinsulinemic–euglycemic clamps at the Mouse Phenotyping, Physiology and Metabolism Core at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine as previously described4. We infused human insulin at 2.5 mU kg−1 min−1, we maintained blood glucose concentration between 120 mg dl−1 and 140 mg dl−1 by infusing 20% glucose at various rate. For gene expression analysis under the euglycemic clamp condition, we clamped the mice similarly, except that we infused the control mice with phosphate–buffered saline instead of insulin (10 mU kg−1 min−1) and the clamp lasted for 3 hours, during which we maintained the blood glucose concentration between 120 mg dl−1 and 140 mg dl−1.

Statistical Analysis

We presented all data as means ± s.e.m. We performed the statistical analysis with one–way ANOVA when more than two groups of data were compared, with two–way ANOVA when two conditions were involved, and with student’s t–test when only two groups of data were concerned. We deemed the difference being significant when P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank M. Magnuson (Vanderbilt University) for kindly providing the antibody to Gck, and D. Accili (Columbia University) for sharing the Foxo1loxP/loxP mice. We are grateful to J. Schug who helped with the microarray data analysis and generated the heatmap and the density plot. The Functional Genomics Core, the Transgenic, Knockout, Mouse Phenotyping, and Biomarker Cores of the University of Pennsylvania Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center (NIH grant P30 DK19525) were instrumental in this work. This work was supported by NIH grant RO1 DK56886 (M.J.B.) and diabetes training grant T32 DK007314 (M.L.).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.L. conceived the hypothesis, designed and performed the experiments, and analyzed the data. M.W. and K.F.L. performed experiments. Q.C., B.R.M. and S.F. provided technical assistance. The R.S.A. lab performed the hyperinsulinemic–euglycemic clamps experiments. K.U. and C.R.K. generated the Akt1loxP/loxP mice. M.J.B. conceived the hypothesis and directed the project. M.L. and M.J.B. prepared the manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Saltiel AR, Kahn CR. Insulin signalling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature. 2001;414:799–806. doi: 10.1038/414799a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White MF. Insulin signaling in health and disease. Science. 2003;302:1710–1711. doi: 10.1126/science.1092952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Selective versus total insulin resistance: a pathogenic paradox. Cell Metab. 2008;7:95–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho H, et al. Insulin resistance and a diabetes mellitus-like syndrome in mice lacking the protein kinase Akt2 (PKB beta) Science. 2001;292:1728–1731. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5522.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michael MD, et al. Loss of insulin signaling in hepatocytes leads to severe insulin resistance and progressive hepatic dysfunction. Mol Cell. 2000;6:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong XC, et al. Inactivation of hepatic Foxo1 by insulin signaling is required for adaptive nutrient homeostasis and endocrine growth regulation. Cell Metab. 2008;8:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen WS, et al. Growth retardation and increased apoptosis in mice with homozygous disruption of the Akt1 gene. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2203–2208. doi: 10.1101/gad.913901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacinto E, et al. SIN1/MIP1 maintains rictor-mTOR complex integrity and regulates Akt phosphorylation and substrate specificity. Cell. 2006;127:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rintelen F, Stocker H, Thomas G, Hafen E. PDK1 regulates growth through Akt and S6K in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:15020–15025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011318098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alessi DR, et al. Characterization of a 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase which phosphorylates and activates protein kinase Balpha. Curr Biol. 1997;7:261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:648–657. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sengupta S, Peterson TR, Sabatini DM. Regulation of the mTOR complex 1 pathway by nutrients, growth factors, and stress. Molecular cell. 2010;40:310–322. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duvel K, et al. Activation of a metabolic gene regulatory network downstream of mTOR complex 1. Molecular cell. 2010;39:171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porstmann T, et al. SREBP activity is regulated by mTORC1 and contributes to Akt-dependent cell growth. Cell metabolism. 2008;8:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTORC1 activates SREBP-1c and uncouples lipogenesis from gluconeogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:3281–3282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000323107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li S, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Bifurcation of insulin signaling pathway in rat liver: mTORC1 required for stimulation of lipogenesis, but not inhibition of gluconeogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:3441–3446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914798107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chakrabarti P, English T, Shi J, Smas CM, Kandror KV. Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 suppresses lipolysis, stimulates lipogenesis, and promotes fat storage. Diabetes. 2010;59:775–781. doi: 10.2337/db09-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim KH, et al. Regulatory role of glycogen synthase kinase 3 for transcriptional activity of ADD1/SREBP1c. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:51999–52006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405522200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rena G, et al. Two novel phosphorylation sites on FKHR that are critical for its nuclear exclusion. EMBO J. 2002;21:2263–2271. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.9.2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rena G, Guo S, Cichy SC, Unterman TG, Cohen P. Phosphorylation of the transcription factor forkhead family member FKHR by protein kinase B. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17179–17183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.17179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakae J, Park BC, Accili D. Insulin stimulates phosphorylation of the forkhead transcription factor FKHR on serine 253 through a Wortmannin-sensitive pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15982–15985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.15982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brunet A, et al. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell. 1999;96:857–868. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng Z, White MF. Targeting Forkhead box O1 from the concept to metabolic diseases: lessons from mouse models. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2011;14:649–661. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puigserver P, et al. Insulin-regulated hepatic gluconeogenesis through FOXO1-PGC-1alpha interaction. Nature. 2003;423:550–555. doi: 10.1038/nature01667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, et al. A fasting inducible switch modulates gluconeogenesis via activator/coactivator exchange. Nature. 2008;456:269–273. doi: 10.1038/nature07349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Accili D, Arden KC. FoxOs at the crossroads of cellular metabolism, differentiation, and transformation. Cell. 2004;117:421–426. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang W, et al. FoxO1 regulates multiple metabolic pathways in the liver: effects on gluconeogenic, glycolytic, and lipogenic gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10105–10117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumoto M, Han S, Kitamura T, Accili D. Dual role of transcription factor FoxO1 in controlling hepatic insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2464–2472. doi: 10.1172/JCI27047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Brien RM, Streeper RS, Ayala JE, Stadelmaier BT, Hornbuckle LA. Insulin-regulated gene expression. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:552–558. doi: 10.1042/bst0290552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biggs WH, 3rd, Meisenhelder J, Hunter T, Cavenee WK, Arden KC. Protein kinase B/Akt-mediated phosphorylation promotes nuclear exclusion of the winged helix transcription factor FKHR1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7421–7426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsumoto M, Pocai A, Rossetti L, Depinho RA, Accili D. Impaired regulation of hepatic glucose production in mice lacking the forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 in liver. Cell Metab. 2007;6:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haeusler RA, Kaestner KH, Accili D. FoxOs function synergistically to promote glucose production. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:35245–35248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.175851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altomonte J, et al. Inhibition of Foxo1 function is associated with improved fasting glycemia in diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E718–E728. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00156.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samuel VT, et al. Targeting foxo1 in mice using antisense oligonucleotide improves hepatic and peripheral insulin action. Diabetes. 2006;55:2042–2050. doi: 10.2337/db05-0705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Easton RM, et al. Role for Akt3/protein kinase Bgamma in attainment of normal brain size. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1869–1878. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.5.1869-1878.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang L, Rubins NE, Ahima RS, Greenbaum LE, Kaestner KH. Foxa2 integrates the transcriptional response of the hepatocyte to fasting. Cell metabolism. 2005;2:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakoda H, et al. Differing roles of Akt and serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase in glucose metabolism, DNA synthesis, and oncogenic activity. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:25802–25807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301127200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daitoku H, Yamagata K, Matsuzaki H, Hatta M, Fukamizu A. Regulation of PGC-1 promoter activity by protein kinase B and the forkhead transcription factor FKHR. Diabetes. 2003;52:642–649. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perrot V, Rechler MM. The coactivator p300 directly acetylates the forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 and stimulates Foxo1-induced transcription. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2283–2298. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Vos KE, Coffer PJ. The extending network of FOXO transcriptional target genes. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2011;14:579–592. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirota K, et al. A combination of HNF-4 and Foxo1 is required for reciprocal transcriptional regulation of glucokinase and glucose-6-phosphatase genes in response to fasting and feeding. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32432–32441. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nature cell biology. 2002;4:648–657. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kovacina KS, et al. Identification of a proline-rich Akt substrate as a 14-3-3 binding partner. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:10189–10194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210837200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: insights into insulin action. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2006;7:85–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leavens KF, Easton RM, Shulman GI, Previs SF, Birnbaum MJ. Akt2 is required for hepatic lipid accumulation in models of insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2009;10:405–418. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slack C, Giannakou ME, Foley A, Goss M, Partridge L. dFOXO-independent effects of reduced insulin-like signaling in Drosophila. Aging Cell. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00707.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van der Horst A, Burgering BM. Stressing the role of FoxO proteins in lifespan and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:440–450. doi: 10.1038/nrm2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Partridge L, Bruning JC. Forkhead transcription factors and ageing. Oncogene. 2008;27:2351–2363. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamagata K, et al. Arginine methylation of FOXO transcription factors inhibits their phosphorylation by Akt. Mol Cell. 2008;32:221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Housley MP, et al. O-GlcNAc regulates FoxO activation in response to glucose. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16283–16292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802240200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang H, et al. Skp2 inhibits FOXO1 in tumor suppression through ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1649–1654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406789102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van der Vos KE, Coffer PJ. FOXO-binding partners: it takes two to tango. Oncogene. 2008;27:2289–2299. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okamoto H, Obici S, Accili D, Rossetti L. Restoration of liver insulin signaling in Insr knockout mice fails to normalize hepatic insulin action. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115:1314–1322. doi: 10.1172/JCI23096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gelling RW, et al. Insulin action in the brain contributes to glucose lowering during insulin treatment of diabetes. Cell metabolism. 2006;3:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Obici S, Zhang BB, Karkanias G, Rossetti L. Hypothalamic insulin signaling is required for inhibition of glucose production. Nature medicine. 2002;8:1376–1382. doi: 10.1038/nm1202-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hill JW, et al. Direct insulin and leptin action on pro-opiomelanocortin neurons is required for normal glucose homeostasis and fertility. Cell metabolism. 2010;11:286–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Inoue H, et al. Role of hepatic STAT3 in brain-insulin action on hepatic glucose production. Cell metabolism. 2006;3:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wan M, et al. Loss of Akt1 in mice increases energy expenditure and protects against diet-induced obesity. Molecular and cellular biology. 2011 doi: 10.1128/MCB.05806-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Summers SA, Whiteman EL, Cho H, Lipfert L, Birnbaum MJ. Differentiation-dependent suppression of platelet-derived growth factor signaling in cultured adipocytes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:23858–23867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.23858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miller RA, et al. Adiponectin suppresses gluconeogenic gene expression in mouse hepatocytes independent of LKB1-AMPK signaling. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:2518–2528. doi: 10.1172/JCI45942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.