Abstract

VDAC is now universally accepted as the channel in the mitochondrial outer membrane responsible for metabolite flux in and out of mitochondria. Its discovery occurred over two independent lines of investigation in the 1970’s and 80’s. This retrospective article describes the history of VDAC’s discovery and how these lines merged in a collaboration by the authors. The article was written to give the reader a sense of the role played by laboratory environment, personalities, and serendipity in the discovery of the molecular basis for the unusual permeability properties of the mitochondrial outer membrane.

The basic permeability properties of the mitochondrial outer membrane were determined in 1957[1]. Werkheiser and Bartley showed that the outer membrane is permeable to small molecules, and for two decades it was generally assumed that the outer membrane is “leaky”. The leakiness of the outer membrane allowed mitochondrial researchers to largely ignore this membrane in favor of the inner membrane. The discovery of the fundamental basis for oxidative phosphorylation and the establishment of the Chemiosmotic Hypothesis[2], a remarkable triumph that transformed the study of membrane transport and energy transduction, all took place with little or no consideration of the role of the outer membrane. At the same time, biochemists were rediscovering the structure of membranes, a structure that physiologists like Cole and Curtis and Hodgkin and Huxley largely understood thanks to the pioneering work of Gorter and Gendel [3] and Davson and Danielli[4]. The Fluid Mosaic Model [5] became generally accepted by the mid ‘70s. An understanding of the fundamental barrier function of this 2-dimensional fluid was established1 when Alan Finkelstein demonstrated that non-electrolytes permeate by a solubility-diffusion mechanism[6]. Despite these advances, the notion of a “leaky” mitochondrial outer membrane persisted through the ‘70s, although it was unclear whether its leakiness was due to damage incurred during mitochondrial isolation or to a “remarkable” structural property[7]. Strong evidence that there was, in fact, a structural basis for the mitochondrial outer membrane’s unusual permeability, namely VDAC channels, would soon follow.

The discovery of channels in the outer membrane of mitochondria occurred in two independent ways: electron microscopic observations and electrophysiological measurements. The relatively small size of the VDAC channel would have made it difficult to visualize in electron micrographs were it not for its propensity to form distinctive, close-packed arrays in the outer membrane of plant mitochondria[8]. The reason for the large number of VDAC channels in mitochondria from plants is still unclear. At the time some suspected that the densely packed, negative-stain-filled “pits” seen by EM might be an artifact of lipid phase separation, induced by drying the membranes in the heavy-metal stains used for contrast. However, this was later shown not to be the case and the negative-stain-filled “pits” in the outer membrane were, in fact, proven to be pores formed by VDAC. The identification of the functional VDAC channel had an even more circuitous origin. This retrospective article tells the story of how these two lines of investigation originated independently and rapidly converged. These were firmly connected by the use of polyclonal antibodies that both labeled the channels in mitochondrial outer membranes and interfered with VDAC channel reconstitution[9].

The discovery and naming of the VDAC channel…Marco Colombini

The existence of channels in membranes was hypothesized well before single-channel recordings were made. The recording of currents across the plasma membrane of cells by impaling a cell with a microelectrode, succeeded in recording the behavior of populations of channels. It was not until the formation of planar membranes by Mueller and coworkers [10] that single channels were recorded. However, these single channels were not the channels typically found in membranes. They were channel-forming antibiotics that could be reconstituted into the planar membranes. VDAC was the first intrinsic membrane channel reconstituted and studied at the single-channel level[11]. Some time thereafter, the patch-clamp technique[12] allowed almost routine recording of single channels.

The discovery of the VDAC channel was the result of a failed attempt to reconstitute a voltage-gated calcium channel from Paramecium aurelia. Stan Schein, then an MD-PhD student at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, had generated mutant Paramecia with altered behavior that was likely the result of mutant calcium channels [13]. He hoped to reconstitute the normal and then the mutant calcium channels and asked me to collaborate on the effort. I was then a post-doc in Alan Finkelstein’s laboratory. The Finkelstein lab focused on the study of channel-forming antibiotics and used the recently-developed planar membrane systems. As a new post-doc, first to study Na+-coupled amino-acid transport in membrane vesicles[14], I naively thought, based on questionable reports in the literature, that reconstitution of these transporters into planar membranes was a proven possibility. Lack of success in this effort and a meeting with Stan resulted in the collaboration.

The environment in the Finkelstein lab was an unusual combination of rigorous science and the freedom to explore the unexplored, no matter how wild and improbable. It was a terrific environment in which to make discoveries. Taking our cue from the pioneering work of Efraim Racker [15], we sonicated Paramecium membranes with an excess of asolectin, a mixture of soybean phospholipids in which mitochondrial redox complexes work rather well. To attempt reconstitution of channels, we used the monolayer method of Montal and Mueller [16] to make planar membranes. In order to make the starting monolayers containing the proteins, we lyophilized the sonicated mixture and then dispersed it into hexane. We reasoned that completely hydrophobic hydrocarbons would be mild and not denaturing, and the proteins and lipids ought to form inverted micellar structures in the hydrocarbon. After layering the dispersion on the aqueous surface and allowing the hexane to evaporate, membranes were formed from the resulting monolayers.

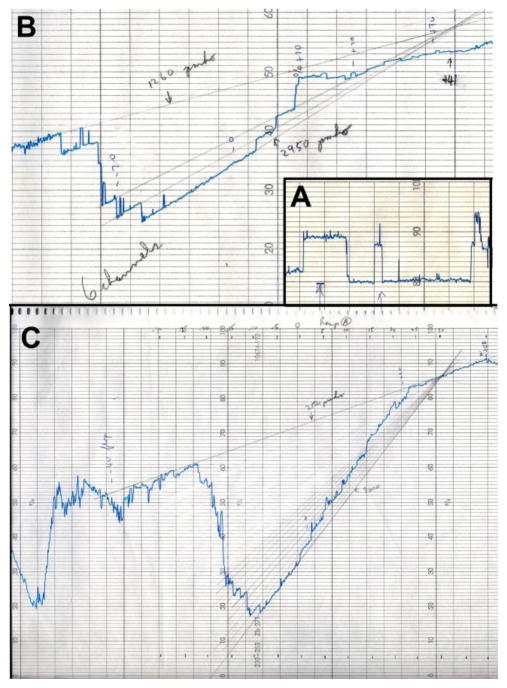

Almost right away we noticed something unusual in the conducting membrane. There was a conductance that depended on the applied voltage. There was a single discrete change in conductance over and above the unidentified background conductance (Fig. 1A). We observed with fascination this voltage-dependent transition, trying to understand the underlying logic. All this activity was being recorded on chart paper and soon the paper ran out. Not having a spare roll, we turned the paper around and rolled it back on the spool so that we could continue to record in the back of the paper. The membrane lasted a long time but finally broke. When we tried to repeat the experiment the next day, we could not form a stable membrane. The excitement of the previous day transformed into frustration. We soon suspected that contaminating protein might be the problem and took apart the chamber for a thorough cleaning. When we finally were able to make membranes reasonably consistently, from time to time we observed this single voltage-dependent conducting channel. The obvious question: What was this channel? Was it the calcium channel? Since it was voltage-gated, it must be involved in the excitable behavior of Paramecium… or so we thought.

Fig. 1.

Early electrophysiological records of VDAC channels from Paramecium. Paramecium membranes were sonicated with a 20 fold mass excess of asolectin (soybean phospholipids), freeze-dried and suspended in hexane prior to layering on the surface of aqueous solutions to form monolayers and then planar bilayer membranes. The amplifier used inverted the current so that downward current is positive, downward transitions are channel openings and upward, channel closings. A. A segment of a current record taken on April 24, 1975, the first experiment performed with VDAC channels. The single-channel fluctuations were recorded under an applied potential of 50 mV in the presence of 0.1 M KCl in the aqueous solution. B. Recording (May 25th, 1975) of the voltage dependence of VDAC channels in the presence of a CaCl2 gradient (80 mM CaCl2 vs 20 mM CaCl2), the pH maintained at 7.5 with 1 mM Tris buffer. The voltage was changed linearly between +70 and −70 mV. Some of the values are recorded in pencil. There are 6 VDAC channels in the membrane closing around −20 mV. C. The same membrane as in (B) but later in the experiment after more channels had inserted. The voltage was changed linearly between +40 and −40 mV (the voltage values are indicated on top). Channel closure resulted in a remarkable region of negative slope conductance. By extrapolating the current lines back to their intercept, the reversal potential of the voltage-dependent portion of the conductance was obtained. The positive reversal potential on the high Ca2+ ion side demonstrated that the channels were highly selective for Cl− over Ca2+.

To determine if the characteristics of the channel were consistent with a calcium channel, we made a membrane in the presence of a 10-fold gradient of KCl. This experiment produced both excitement and initial disappointment. Rather than observing one lonely channel, dozens of identically-behaving channels were present in the membrane. The voltage dependence caused a staircase of channel opening and closures as the applied voltage was ramped from −60 mV to +60 mV. This was not some strange artifact! Instead, we were observing a set of single channels responsible for a voltage-gated conductance. The hypothesis that voltage-gating was the result of voltage altering the probability of individual channels opening and closing was evident. Previous results with EIM (excitability-inducing material) had shown similar results[17], but the difference was that we were studying a channel from the membranes of Paramecia, not a contaminant from a sample of ovalbumin. If it wasn’t for the accidental discovery that the salt gradient greatly favored channel insertion, this line of research would likely have stopped. Observing many identical channels all gating with the same properties, demanded our complete dedication.

The disappointing aspect of these experiments came from our measurement of the reversal potential of the channels, which showed that they favored anions over cations. This selectivity was unexpected, since the transformative and pioneering work of Hodgkin and Huxley [18]showed that electrical excitability arose from the voltage-gated conductance of cations, primarily Na+ and K+, and of course, we were hoping and expecting to find channels that fluxed Ca++.

Moreover, further experiments in the presence of a CaCl2 gradient showed clearly that the channels greatly favored chloride over calcium (Fig. 1B, C). These were not calcium channels! What were they? Where did they come from? We therefore fractionated Paramecia and tried to reconstitute channels from each membrane fraction. We found that the channel-forming activity came from mitochondria. This was a shock! Peter Mitchell’s Chemiosmotic Hypothesis required that the mitochondrial inner membrane be a barrier to the free flow of ions, especially protons, so as to maintain the proton motive force. Thus the presence of channels in that membrane seemed unlikely. Yet, since the channels closed with voltage more negative than −40 mV, perhaps these were normally closed. Certainly, since the outer membrane is leaky, these channels would serve no function in that membrane.

In writing the first paper on these channels, we needed to come up with a name. We were influenced to use an acronym by the wonderful papers on EIM[17]. We wanted to include the critical features of the channel: voltage gating and anion selectivity. We thought of Voltage Sensitive Anion Channel, VSAC, but it sounded too militaristic. We agreed upon VDAC (Voltage Dependent Anion Channel). We decided on first authorship by flipping a coin.

In thinking about a possible role for VDAC, we turned to the fact that brown fat mitochondria were naturally uncoupled, reportedly due to an anion permeability, perhaps due to the presence of VDAC channels. We wondered if brown fat mitochondria might have lost their voltage-dependent closure. By then we had reconstituted virtually identical channels from rat liver mitochondria. We therefore housed rats in a cold room to activate their brown fat, but we found that channels reconstituted from brown fat mitochondria had properties identical to those from rat liver mitochondria.

A further blow to the notion that VDAC played a role in the inner membrane was the discovery that channels inserted spontaneously into an unmodified planar membrane when a small amount of detergent-solubilized mitochondrial protein was stirred into the aqueous solution. In these experiments, we found that channel closure resulted in transition into a lower conducting state rather than the total loss of conductance. In addition, the closed state favored cations. Clearly, this closed-state conductance would be incompatible with maintaining the proton motive force. Finally, experiments that separated outer from inner mitochondrial membrane showed that VDAC was located in the outer membrane[11]. Finally it became clear that VDAC must be the reason why the outer membrane is leaky. In the 1979 Nature paper[19] I proposed for the first time that the permeability of the outer membrane functionally described by Werkheiser and Barley was due to the presence of VDAC channels. Although strongly suggestive, firmly linking these channels to the arrays in the outer membrane described by Parsons, Bonner and Mannella would require another 5 years and a collaboration with Carmen Mannella.

While these investigations were occurring, Hiroshi Nikaido and others were studying channels in the outer membrane of bacteria, channels collectively referred to as porins. Nikaido speculated that similar channels might exist in mitochondria. A year after the publication of the Nature paper[19] proposing that VDAC could be responsible for the permeability of the mitochondrial outer membrane, Zalman, Nikaido and Kagawa[20] published a paper in JBC reporting that the outer membrane contained “non-specific diffusion channels”. This paper is the origin of the term “mitochondrial porin” and the notion that these channels are non-specific. Certainly from what they knew, the channels seemed to be non-specific. Only later did it become clear that VDAC channels show a high degree of specificity although only for anionic molecules large enough to feel the distribution of electrical potential along the inner surface of the VDAC channel[21].

Whether VDAC channels are related to the “porins” is still unclear. Equating the mitochondrial outer membrane to the outer membrane of gram negative bacteria is attractive. Alternatively, the mitochondrial outer membrane is sometimes considered related to the endoplasmic reticulum and might have derived from an endosome-like membrane that engulfed the original endosymbiotic bacterium that evolved into the mitochondrion. Thus, arguments based on biological origins are not very useful. Once sequences became available, essentially no homology was found between bacterial porins and VDACs. This was an equally equivocal result, given the 1.5 billion years since the endosymbiotic event from which the first eukaryotes derived.

Seeing is believing: the hunt for VDAC using electron microscopy…Carmen Mannella

The first negative-stain electron microscopy (EM) studies of plant mitochondrial membranes, showing densely packed stain-filled subunits, resulted from a collaboration that included Walter Bonner, at the Johnson Foundation (JF) of the University of Pennsylvania, and Donald Parsons, then at the University of Toronto[8]. In 1965 they speculated that the 2–3 nm wide “pits”, not seen in animal mitochondrial outer membranes, were pores that might explain the unique ability of plant mitochondria to respire with externally added NADH, reasoning the outer membrane would otherwise be a permeability barrier to the relatively large dinucleotide. Only later was it determined that this property of plant mitochondria was due a novel NADH dehydrogenase on the inner membrane facing the inter-membrane space [22].

I would meet Parsons in the ‘70s after he moved to the Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo. I met Bonner in 1969 when I arrived at the JF as a graduate student in biophysics. He was a plant physiologist equally famous for his good humor and for his studies of plant cyanide-insensitive alternative oxidase. His laboratory at the JF was a haven for open exploration of all things interesting having to do with plants and (usually but not exclusively) their mitochondria. Coincidentally, another JF graduate student at the time was Mauricio Montal who, after completing his thesis research with Britton Chance, would develop (with P. Mueller) the bilayer technique[16] that enabled the electrophysiological studies of VDAC undertaken at Einstein in the mid ‘70s.

Members of the Bonner lab bonded through several communal rituals. There was the daily rite of picking and cutting mung beans or peeling and slicing potatoes for that day’s mitochondrial prep. (Mitochondrial yields from plant vs. animal tissue, gram for gram, are depressingly low.) In the early spring, we could be found slogging with the boss through half-frozen swamps in the Pennsylvania countryside, harvesting or sticking thermocouples into skunk cabbages. The prize: to capture (on portable chart recorders) the record for highest temperature differential between a plant (heated by mitochondrial alternative oxidase) and its snow-coated environs. I had the good fortune to arrive in the Bonner lab around the same time as a French postdoc with an extraordinary talent for lipid biochemistry and cell fractionation. While in the Bonner lab, Roland Douce determined how to isolate truly pure fractions of plant mitochondria by sucrose gradient centrifugation. Starting from these ultra clean mitochondria, we worked out how to isolate the component membranes by controlled hypo-osmotic lysis of the outer membrane, carefully monitored by cyctochrome c release, and gradient purification[22]. Under his and Bonner’s tutelage, I proceeded to characterize pure mitochondrial outer membranes biochemically and structurally for my thesis.

Two aspects of my PhD research related directly to the VDAC story. First, SDS-PAGE of the mitochondrial outer membranes (done in the lab of Nam-Hai Chua at Rockefeller University) showed that more than 50% of the protein mass of the membrane was associated with a single ~30 kD peak that was unusually resistant to trypsin, which I imaginatively named Band I[23]. Later western analysis would show Band I to be VDAC. The preponderance of a single protein in this membrane could explain the presence of the arrays easily detected by EM, analogous to those of connexin complexes in gap junction plaques and of acetylcholine receptors in Torpedo synaptic membranes. Second, x-ray scattering from hydrated outer membranes (done in the lab of Kent Blasie at Penn), oriented by ultracentrifugation into multi-lamellar stacks, displayed strong off-axial, equatorial maxima characteristic of prominent in-plane subunit structure[24]. Patterson function analysis of this diffraction was consistent with an average in-plane spacing between subunits of 65 Å, consistent with the packing of the pore-like subunits first seen in electron micrographs by Parsons and Bonner years earlier. Naturally, I speculated in my thesis that Band I was an integral membrane protein responsible for the pore-like substructure of the mitochondrial outer membrane.

After finishing my PhD in 1974, I moved on to other things, including a postdoctoral position at St. Louis University to learn mitochondrial molecular biology with Alan Lambowitz, another postdoc from the Bonner lab. Lambowitz’s favorite model system was Neurospora crassa, which we jokingly considered a plant without chloroplasts, since it had an inducible alternative oxidase and a vacuole. My stay in St. Louis was an intense two years of discovery, including characterization of spontaneous mitochondrial DNA deletion mutations and heteroplasmy (since associated with aging and disease in humans), and RNA splicing in ribosomal RNA. From the perspective of the VDAC story-line, however, the important event was simply my learning how to grow and isolate mitochondria from N. crassa.

In 1979 I accepted a position at the New York State Department of Health’s Division of Laboratories and Research (now the Wadsworth Center) in Albany, NY, where Donald Parsons had established a high-voltage electron microscopy (HVEM) laboratory. I had postdoc’d with Parsons at Roswell Park after graduate school and welcomed the chance to start a membrane structure lab. Among the other young scientists in the HVEM group was Joachim Frank, an expert in electron optics who was creating a modular software system (SPIDER) for electron microscopic image processing – a system now used worldwide in scores of labs. Since Parsons and I both had an interest in mitochondria, it was natural to use them as test objects for EM techniques being developed by the HVEM group, such as dark-field imaging. Since I had just come from an N. crassa lab, and to my knowledge no one had yet looked at their outer membranes by EM, that is where I began.

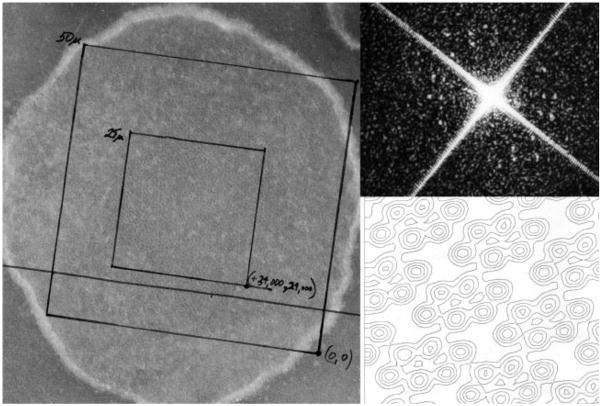

Using a variety of negative stain conditions, I recorded hundreds of images of fungal outer membranes, isolated with a protocol slightly modified from that developed for plant mitochondria. Fungal mitochondria required a larger hypo-osmotic shock to lyse and detach their outer membranes. At first, I did not see what I was hoping for: membrane surfaces packed with pores like those of plant mitochondria. This despite the fact that SDS PAGE indicated an even higher fraction (~ 70%) of the 30 kD “Band I” protein in N. crassa outer mitochondrial membranes than in the plant membranes. Marco Colombini had just published his 1979 Nature paper on VDAC and there was no doubt in my mind that Band I was VDAC. After a few weeks, a small fraction (perhaps 5–10%) of membranes in one outer membrane preparation could be seen to contain distinct striated patches. Closer examination indicated the striations were rows of densely stained pores, like those in the plant membranes but in ordered patterns. Taking the negatives to a laser optical diffractometer showed Bragg diffraction, confirming the presence of true 2D crystals on the membranes. The next step was image processing. We digitized the membrane images and, using a technique called Fourier lattice filtration (implemented in SPIDER to study cytochrome oxidase membrane crystals), were able to separately visualize the two overlapped 2D membrane crystals in each collapsed outer membrane vesicle[25]. The first image processed in this way is shown in Figure 2. It is exciting to see something in nature for the first time, and the discovery of the mitochondrial outer membrane pore crystals was no exception. Depending on the behavior of the crystals and our skills, we knew a door was opening through which we could obtain detailed structural information about the protein responsible for the permeability properties of the mitochondrial outer membrane in its native membrane environment.

Fig. 2.

Visualization by electron microscopy of VDAC pores in the mitochondrial outer membrane. Left: First electron micrograph (recorded in January, 1980) of 2D crystalline arrays of pores in an outer membrane (~ 400 nm across) from N. crassa mitochondria. The specimen was negatively stained with phosphotungstate. Boxes were drawn on the print to guide digitization on a scanning microdensitometer. Upper right: Optical diffraction pattern indicating the presence of two 2D crystal lattices in the center of the collapsed membrane vesicle. (The bright “X” is an optical artifact from the square mask used to delineate the region on the negative illuminated by the laser beam.) Lower right: Density contour map showing the rows of unit cells, each containing six pores, in one of the two overlapped 2D crystals in the membrane vesicle, as revealed by Fourier lattice filtration of the digitized image. This subfield is ~ 40 nm across.

Before proceeding through that door, however, we needed to establish conclusively that the 2D crystals were, in fact, composed of VDAC. The critical experiment was a collaboration with Marco Colombini, employing a polyclonal rabbit antibody that we raised and could show, by a sensitive in-gel radio-immune assay, specifically labeled the ~30-kD outer-membrane protein. This antibody both inhibited VDAC insertion into planar bilayers in Colombini’s lab and bound selectively to the crystalline arrays in outer mitochondrial membrane fractions as visualized in EM by labeling with immuno-gold bound to secondary antibodies[9]. This experiment completed the circle, confirming the hypothesis dating back 10 years that the pores observed by EM were, in fact, formed by the “Band I” protein, which in fact was VDAC.

In the ensuing 15 years, we learned a great deal about the structure of VDAC from EM studies of the N. crassa membrane crystals, prepared in negative stains and later in native, frozen-hydrated state. These studies were made possible by a stroke of inductive reasoning, or perhaps simple luck. In trying to understand the variable occurrence of 2D crystals in our outer membrane preparations, we found that micromolar Ca2+ moderately improved the crystal yield. I recalled that a Ca2+-activated phospholipase A2 was resident on the outer membrane of liver mitochondria and reasoned that turning on this enzyme might facilitate membrane protein crystallization by slowly depleting membrane lipids. So we incubated freshly isolated outer membranes overnight with bee venom phospholipase A2 under continuous dialysis and, on the very first try, achieved a 2D crystal yield of over 50%. This finding was published in Science[26] and later used with success by others for generating or improving the quality of several types of membrane protein crystals, including bacterial porins. Unfortunately, our own goal of an atomic-resolution structure for VDAC in the mitochondrial outer membrane eluded us. The 2D VDAC crystals proved to be too small for electron diffraction and, worse, displayed complex lattice polymorphism that prevented merging of the large 3D cryo-EM data sets needed to approach atomic resolution. But the information about VDAC provided by our EM studies with these crystals, despite their flaws, established the basic structural parameters of this important pore-forming protein in its native membrane.

Recent history and future prospects

This retrospective article passes over a tremendous amount of research into the function and structure of VDAC conducted in the labs of the authors and elsewhere from the mid-1980s to the present. The intent is not to slight these achievements. Rather this article was written to give the reader a sense of the role played by laboratory environment, personalities, and serendipity in the discovery of VDAC and thus the molecular basis for the unusual permeability properties of a membrane. Another consideration in our choice of timeframe is that the basic achievements covered are not controversial – at least to our knowledge. As research into the structure and function of VDAC has become more sophisticated and complex, it has become more interesting in several ways, one of them being the differences of opinion and controversies that have arisen on numerous issues. Since even the authors have disparate thoughts on a few issues, ending the story in the mid-1980s made its writing simpler.

Following the discovery of VDAC there was a long phase during which VDAC research was performed by only a very small number of investigators. This changed as the perceived role of the outer membrane expanded and the diverse properties of VDAC were revealed. The current realization that drives the field is that VDAC is at the nexus of the complex interplay between the mitochondrion, an organelle with eubacterial roots, and the eukaryotic cells within which it has co-evolved for 1.5 billion years.

VDAC research in the 21st century is a cauldron, bubbling with challenges and opportunities, and stirred by major lingering unresolved questions and ongoing controversies. Some of the challenges include defining VDAC’s role in regulating mitochondrial metabolism and energy transduction, its role in apoptosis, and the functions of isoforms and post-translational modifications, including those unrelated to channel-forming ability. For instance, we are at a loss to explain the phenotypes of mice missing individual VDAC isoforms. Some of the unresolved questions are the role of VDAC’s highly conserved voltage gating properties, the native (i.e., mitochondrial membrane) structures of VDAC, the regulation of VDAC, and the VDAC interactome. Among the many controversies, some are tending toward resolution. For example, the preponderance of evidence against VDAC’s location in the plasma membrane, role in the mitochondrial permeability transition, and direct role in cytochrome c efflux during apoptosis has proven convincing to most followers of the VDAC story. While disappointing to some, these negative conclusions only marginally decrease the number of roles still attributed to this small protein. The reality is that, despite the tremendous progress that has been made on several fronts, the VDAC field has barely begun to be explored. We are at the end of the beginning of a story in which there are certain to be many more exciting discoveries and surprises.

Highlights.

the discovery of the VDAC channel by recording its electrophysiological properties

the discovery of the VDAC channel by electron microscopy

the interesting historical events surrounding the discoveries

Acknowledgments

Most of the mentors and collaborators who played key roles in the discovery of VDAC are named in this article. There are many other technical specialists, students and postdocs, too numerous to mention, who made important contributions to the studies of VDAC during the period covered by this article and shortly afterwards. M.C. would like to express his profound indebtedness to Alan Finkelstein, a truly underappreciated genius, who made the discovery of VDAC channels possible. Thanks also to M.C.’s partner in discovery, Stan Schein, for constructive comments on parts of this work and to Susan Murphy for invaluable assistance. C.M. thanks Michael Marko for teaching him electron microscopy from the bottom up and Bernard Cognon for collecting most of the EM data from the VDAC outer membrane crystals over the years. The work on VDAC in the lab of Alan Finkelstein was funded by the National Science Foundation. M.C. was supported by a fellowship from the Medical Research Council of Canada. Mitochondrial outer membrane research in the laboratories of Walter Bonner and C.M. was funded by the National Science Foundation. The authors gratefully acknowledge this support, without which their research on VDAC would not have been possible.

Footnotes

In his papers on the subject, Dr. Finkelstein clearly states that physiologists accepted that plasma membrane permeability functions by a lipoidal sieve mechanism. However, Dr. Finkelstein clearly demonstrated experimentally that the permeability of the lipid bilayer portion of membranes is determined by solubility diffusion of the solute. The size of the solute is irrelevant except as it affects the diffusion constant. This fundamental understanding is still not fully appreciated by many students and researchers alike.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Werkheiser WC, Bartley W. Study of steady-state concentrations of internal solutes of mitochondria by rapid centrifugal transfer to a fixation medium. Biochem J. 1957;66:79–91. doi: 10.1042/bj0660079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell P, Moyle J. Evidence discriminating between chemical and chemiosmotic mechanisms of electron transport phosphorylation. Nature. 1965;208:1205–1206. doi: 10.1038/2081205a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorter E, Grendel F. On bimolecular layers of lipids on the chromocytes of the blood. J Exp Med. 1925;41:439–443. doi: 10.1084/jem.41.4.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danielli JF, Davson H. A contribution to the theory of permeability of thin films. J Cell Compar Physl. 1935;5:495–508. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singer SJ, Nicolson GL. Fluid mosaic model of structure of cell-membranes. Science. 1972;175:720–731. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4023.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orbach E, Finkelstein A. The non-electrolyte permeability of planar lipid bilayer-membranes. J Gen Phys. 1980;75:427–436. doi: 10.1085/jgp.75.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Depierre JW, Ernster L. Enzyme topology of intracellular membranes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1977;46:201–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.001221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parsons DF, Bonner WD, Verboon JG. Electron microscopy of isolated plant mitochondria and plastids using both thin-section and negative-staining techniques. Can J Botany. 1965;43:647–655. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mannella CA, Colombini M. Evidence that the crystalline arrays in the outer-membrane of neurospora mitochondria are composed of the voltage-dependent channel protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;774:206–214. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(84)90293-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mueller P, Rudin DO, Tien HT, Wescott WC. Reconstitution of cell membrane structure in vitro and its transformation into an excitable system. Nature. 1962;194:979–980. doi: 10.1038/194979a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schein SJ, Colombini M, Finkelstein A. Reconstitution in planar lipid bilayers of a voltage-dependent anion-selective channel obtained from paramecium mitochondria. J Membr Biol. 1976;30:99–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01869662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neher E, Sakmann B. Single-channel currents recorded from membrane of denervated frog muscle-fibers. Nature. 1976;260:799–802. doi: 10.1038/260799a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schein SJ, Bennett MV, Katz GM. Altered calcium conductance in pawns, behavioural mutants of Paramecium aurelia. J Exp Biol. 1976;65:699–724. doi: 10.1242/jeb.65.3.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colombini M, Johnstone RM. Na+ gradient-stimulated AIB transport in membrane-vesicles from Ehrlich ascites-cells. J Membr Biol. 1974;18:315–334. doi: 10.1007/BF01870120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kagawa Y, Racker E. Partial resolution of enzymes catalyzing oxidative phosphorylation: XXV. Reconstitution of vesicles catalyzing 32Pi - adenosine triphosphate exchange. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:5477–5487. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montal M, Mueller P. Formation of bimolecular membranes from lipid monolayers and a study of their electrical properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:3561–3566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.12.3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Latorre R, Lecar H, Ehrenste G. Ion transport through excitability-inducing material (EIM) channeled in lipid bilayer membranes. J Gen Phys. 1972;60:72–85. doi: 10.1085/jgp.60.1.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J Physiol-London. 1952;117:500–544. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colombini M. Candidate for the permeability pathway of the outer mitochondrial-membrane. Nature. 1979;279:643–645. doi: 10.1038/279643a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zalman LS, Nikaido H, Kagawa Y. Mitochondrial outer-membrane contains a protein producing nonspecific diffusion channels. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:1771–1774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rostovtseva TK, Komarov A, Bezrukov SM, Colombini M. VDAC channels differentiate between natural metabolites and synthetic molecules. J Membr Biol. 2002;187:147–156. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0159-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Douce R, Mannella CA, Bonner WD. External NADH dehydrogenases of intact plant mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973;292:105–116. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(73)90255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mannella CA, Bonner WD. Biochemical characteristics of outer membranes of plant mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;413:213–225. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(75)90105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mannella CA, Bonner WD. X-ray-diffraction from oriented outer mitochondrial-membranes - detection of in-plane subunit structure. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;413:226–233. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(75)90106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mannella CA. Structure of the outer mitochondrial-membrane - ordered arrays of pore-like subunits in outer-membrane fractions from Neurospora-crassa mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 1982;94:680–687. doi: 10.1083/jcb.94.3.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mannella CA. Phospholipase-induced crystallization of channels in mitochondrial outer membranes. Science. 1984;224:165–166. doi: 10.1126/science.6322311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]