Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of the study is to evaluate the oncologic outcomes of a laparoscopic-assisted right hemicolectomy for the treatment of colon cancer and compare the results with those of previous randomized trials.

Methods

From June 2006, to December 2008, 156 consecutive patients who underwent a laparoscopic right hemicolectomy with a curative intent for colon cancer were evaluated. The clinicopatholgic outcomes and the oncologic outcomes were evaluated retrospectively by using electronic medical records.

Results

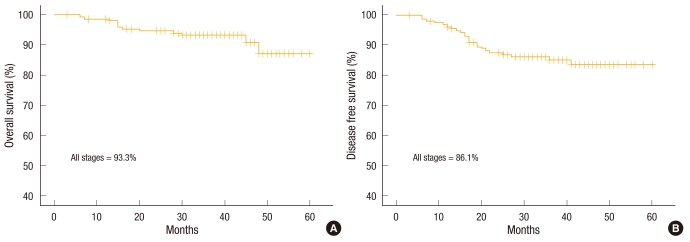

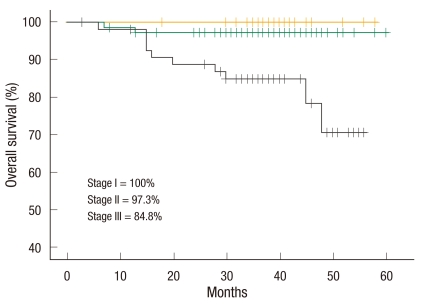

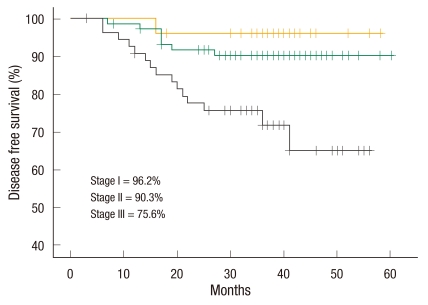

There were 84 male patients and 72 female patients. The mean possible length of stay was 7.0 ± 1.5 days (range, 4 to 12 days). The conversion rate was 3.2%. The total number of complications was 30 (19.2%). Anastomotic leakage was not noted. There was no mortality within 30 days. The 3-year overall survival rate of all stages was 93.3%. The 3-year overall survival rates according to stages were 100% in stage I, 97.3% in stage II, and 84.8% in stage III. The 3-year disease-free survival rate of all stages was 86.1%. The 3-year disease-free survival rates according to stage were 96.2% in stage I, 90.3% in stage II, and 75.6% in stage III. The mean follow-up period was 36.3 (3 to 60) months.

Conclusion

A laparoscopic right hemicolectomy for the treatment of colon cancer is technically feasible and safe to perform in terms of oncologic outcomes. The present data support previously reported randomized trials.

Keywords: Laparoscopy, Colonic neoplasms, Survival rate

INTRODUCTION

The laparoscopic colon resection was first introduced in 1991 [1, 2]. The laparoscopic colectomy has been accepted because of smaller wounds, limited ileus, earlier resumption of dietary intake, and shorter hospital stay compared to open surgery [3-6]. Moreover, the laparoscopic colon resection for malignant disease has been accepted since a large-scale multicenter prospective randomized trial reported the oncologic safety of the laparoscopic-assisted colectomy for colon cancer [7-9]. Recently, the Medical Research Council (MRC) CLASSICC (short-term end points of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer) trial confirmed the oncological safety of laparoscopic colon and rectal surgery [10]. Also, the Clinical Outcome of Surgical Therapy Study Group (COST) trial concluded that the laparoscopic approach was an acceptable alternative to open surgery for colon cancer [7]. According to this evidence, the use of the laparoscopic colorectal resection for cancer has been increasing remarkably in Korea [11-15]. Data retrieved from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment service by the Korean Study Group of Laparoscopic Colorectal Cancer Surgery shows that the annual number in Korea increased yearly and reached 13,683 cases in 2008. The rate of laparoscopic surgery out of the total number of operations for the treatment of colon cancer was 27.8% (3,144/11,325) in 2006. It increased to 49.1% (6,715/13,682) in 2008. The rate of laparoscopic surgery for the treatment of rectal cancer was 24.5% (1,098/4,478) in 2006 and increased to 48.1% (2,290/4,763) in 2008 [16]. However, few studies have evaluated the oncologic safety of laparoscopic colon surgery for cancer in Korea even though laparoscopic colorectal surgery is increasing in Korea. Thus, the purpose of the present study is to evaluate the oncologic safety of a laparoscopic right hemicolectomy in Korean patients and to compare the present data to data from previous prospective randomized trials.

METHODS

This study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital, was designed as a retrospective and a non-comparative study. From June 2006 to December 2008, 430 laparoscopic colorectal resections for cancer were performed at Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea. Of these, 156 patients underwent curative a laparoscopic-assisted right hemicolectomy for colon cancer (adenocarcinoma, stage I, II, III) by two surgeons (NKK, SHB). The exclusion criteria were patients who underwent palliative surgery, had stage IV cancer and underwent surgery for benign disease. These consecutive 156 patients were enrolled in the present study. The clinicopathologic data and oncologic data were collected from the Yonsei Colorectal Cancer Database. Oncologic data were updated again for the present study by using electronic medical charts and telephone interviews. Missing data were evaluated retrospectively again by reviewing the electronic medical charts.

Patient characteristics, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score [17] and history of previous abdominal surgeries were evaluated. Perioperative clinical outcomes, operative times, bleeding, days to first gas out, days to first soft diet, lengths of stay and readmission rates were evaluated. In the present study, length of stay was recorded as the observed length of stay and possible length of stay. The observed length of stay was the total period from the operation date to the discharge date. The possible length of stay was the hypothetical length of stay according to the discharge criteria. The discharge criteria included tolerance of soft diet and no postoperative complications. In the present study, the possible length of stay was adopted to evaluate the length of stay objectively because many Korean patients want to stay longer in the hospital for no reason.

Postoperative complications were categorized by using the accordion severity-grading system [18]. A mild complication was defined as one that required only a minor invasive procedure that could be done at the bedside, such as insertion of intravenous lines, urinary catheters, and nasogastric tubes, and drainage of wound infections. Physiotherapy and the following drugs were allowed: antiemetics, antipyretics, analgesics, diuretics, electrolytes, and physiotherapy. A moderate complication was defined as one that required pharmacologic treatment with drugs other than what was allowed for minor complications, for instance, antibiotics. Blood transfusions and total parenteral nutrition were also included. A severe complication was defined as all complications requiring endoscopic or interventional radiologic procedures or re-operation, as well as complications resulting in failure of one or more organ systems [18].

Conversion was defined as the need for a laparotomy at any time to complete the whole surgical procedure. For the postoperative pathologic results, the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage (American Joint Committee on Cancer, 6th edition [19]), grade of tumor differentiation, distal and proximal resection margins, and the number of harvested lymph nodes were evaluated. Recurrence was defined as the presence of radiologically-confirmed or histologically-proven tumor. Follow-ups on patients were performed at 1 month, 3 months, then every 3 months until 2 years, and then every 6 months until 5 years. History taking, a physical examination and a tumor marker (carcino embryonic antigen) were evaluated at every visit. A colonoscopy was obtained at the 2-year visit and at the 5-year visit. A colonoscopy was obtained within 1 year if the preoperative colonoscopy was not complete due to an obstructive cancer lesion. Chest and abdominopelvic computed tomography scan were used every 6 months for the detection of local or systemic recurrences. The policy of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients followed the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines [20].

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS ver. 18 (IBM, New York, NY, USA). Overall survival and disease-free survival were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

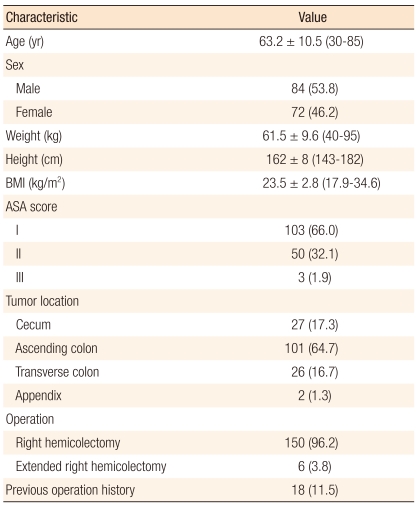

There were 84 male patients and 72 female patients. The mean age was 63.2 ± 10.5 years (range, 30 to 85 years). The mean body mass index was 23.5 ± 2.8 kg/m2 (range, 17.9 to 34.6 kg/m2). The ASA score was I in 103 patients (66.0%), II in 50 patients (32.1%), and III in 3 patients (1.9%). The tumor location was the ascending colon in 101 patients (64.7%), transverse colon in 26 patients (16.7%), cecum in 27 patients (17.3%) and appendix in 2 patients (1.3%). Six patients (3.8%) underwent an extended right hemicolectomy (hepatic flexure in 3 patients, transverse colon in 3 patients). There were previous operation histories in 18 patients (11.5%). Other details are noted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 156)

Values are presented as mean ± SD (range) or number (%).

BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Perioperative clinical results

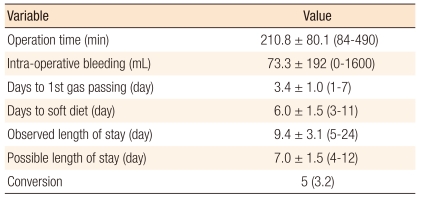

The mean operation time was 210.8 ± 80.1 minutes (range, 84 to 490 minutes). The mean intraoperative bleeding was 73.3 ± 192 mL (range, 0 to 1,600 mL). The mean number of days to 1st gas passing was 3.4 ± 1.0 days (range, 1 to 7 days). The mean number of days to soft diet was 6.0 ± 1.5 days (range, 3 to 11 days). The mean observed length of stay was 9.4 ± 3.1 days (range, 5 to 24 days). The mean possible length of stay was 7.0 ± 1.5 days (range, 4 to 12 days).

The conversion rate was 3.2%. The reasons for conversion were severe adhesion in 2 patients, uncontrolled bleeding in 1 patient, and inadequate surgical space due to obstruction in 2 patients. A re-operation was performed in 1 patient (0.6%). The reason for the re-operation was postoperative anastomosis site bleeding on the operation day. In this case, a segmental resection anastomosis was performed by open surgery (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perioperative clinical outcomes (n = 156)

Values are presented as mean ± SD (range) or number (%).

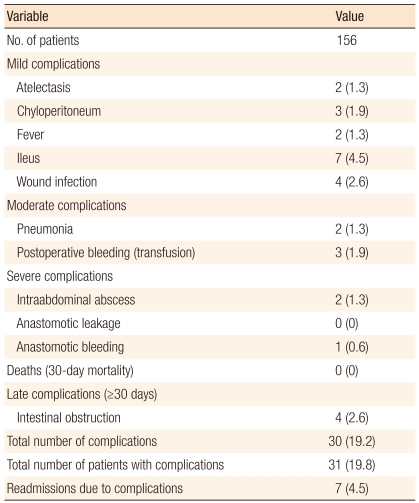

Postoperative complications occurred in 30 patients (19.2%), with the most common complication being ileus in 7 patients (4.5%). The total number of complications was 31 (19.8%). There were no mortalities within 30 days. A late complication was defined as a complication occurring 30 days after the surgery. A late complication was obstruction and occurred in 4 patients (2.6%). Readmission due to complications occurred in 7 patients (4.5%). The reasons for readmission were ileus in 5 patients, wound infection in 1 patient, and intraabdominal abscess in 1 patient (Table 3).

Table 3.

Postoperative clinical outcomes according to the Accordion Severity Grading System [18]

Values are presented as number (%).

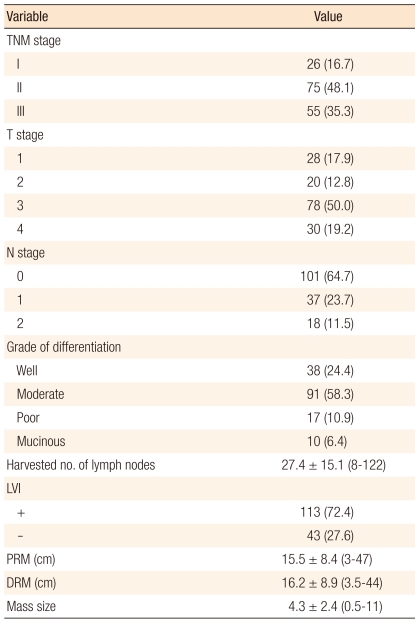

Pathologic results

The distribution of the TNM stage was stage I in 26 patients (16.7%), stage II in 75 patients (48.1%), and stage III in 55 patients (35.3%). Histologic grade of differentiation was well differentiation in 38 patients (24.4%), moderate differentiation in 91 patients (58.3%), poor differentiation in 17 patients (10.9%) and mucinous in 10 patients (6.4%). The mean number of harvested lymph nodes was 27.4 ± 15.1 (range, 8 to 122). The mean proximal resection margin was 15.5 ± 8.4 cm (range, 3 to 47 cm). The mean distal resection margin was 16.2 ± 8.9 cm (range, 3.5 to 44 cm). The mean size of the specimen's mass was 4.3 ± 2.4 cm (range, 5 to 11 cm) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Postoperative pathologic outcomes (n = 156)

Values are presented as number (%) or mean ± SD (range).

TNM, tumor-node-metastasis; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; PRM, proximal resection margin; DRM, distal resection margin.

Oncologic outcomes

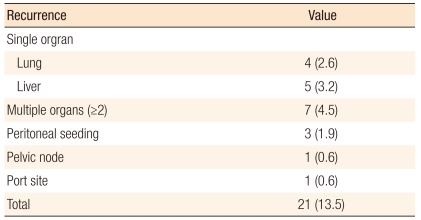

The mean follow-up period was 36.3 months (range, 3 to 60 months). The 3-year overall survival rate was 93.3% in all stages (Fig. 1), 100% in stage I, 97.3% in stage II, and 84.8% in stage III (Fig. 2). The 3-year disease-free survival rate was 86.1% in all stages (Fig. 1), 96.2% in stage I, 90.3% in stage II, and 75.6% in stage III (Fig. 3). All recurrences were systemic recurrences and occurred in the liver (5 patients, 3.2%), the lung (4 patients, 2.6%), multiple organs (7 patients, 4.5%), the peritoneum (3 patients, 1.9%) and the pelvic nodes (1 patient, 0.6%). Port site recurrence was noted in one patient (0.6%) (Table 5).

Fig. 1.

(A) Three-year overall survival rate and (B) 3-year disease-free survival rate.

Fig. 2.

Three-year overall survival rate according to tumor-node-metastasis stage.

Fig. 3.

Three-year disease-free survival according to tumor-node-metastasis stage.

Table 5.

Recurrence pattern

Values are presented as number (%).

DISCUSSION

Postoperative pathologic results can anticipate the long-term oncologic outcomes. The most important issue is the number of harvested lymph nodes. Oncologic resection needs proper regional lymph-node dissection [21, 22]. The suggested minimum number of harvested lymph nodes varies between 6 and 17 [23, 24], and a minimum of 12 lymph nodes is recommended for accurate staging [20]. In the present study, the mean number of harvested lymph nodes was 27.4 ± 15.1, so our results fulfill the previously recommended requirements [19, 20].

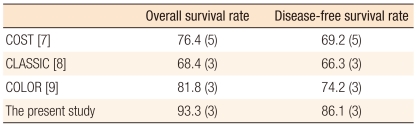

Few studies that have evaluated long-term oncologic outcomes for laparoscopic colectomies for the treatment of colon cancer have been reported even though the laparoscopoic colectomy is accepted widely in Korea [11-15]. The CLASICC trial reported a 3-year overall survival rate of 74.6% and a 3-year disease-free survival rate of 70.9% for the laparoscopic anterior resection group, and those results were not significantly different from the results for the open anterior resection group [8]. In the COST trial, the 3-year overall survival was about 85% in all stages, about 90% in stage I, about 85% in stage II, and about 80% in stage III for the laparoscopic colectomy group (Table 6). These survival results were similar to those for the open colectomy group. In the present study, the 3-year overall survival rate was 93.3%, and the other results were comparable with both the survival results of the CLASICC and the COST trials [7, 8]. Port-site recurrence has been reported to range from 0 to 0.94% [7, 25]. In the present study, port site recurrence was 0.6% and occurred in one patient.

Table 6.

Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for the treatment of colorectal cancer

Values are presented as percentage (year).

COST, Clinical Outcome of Surgical Therapy Study Group; CLASSICC, short-term end points of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer; COLOR, colon cancer laparoscopic or open resection.

A laparoscopic-assisted right hemicolectomy is a minimal invasive approach and shows better short-term outcomes than an open resection [7, 8]. However, Zheng et al. [26] reported a long hospital stay (13.9 ± 6.5 days) in the laparoscopic group, which was even longer (18.3 ± 5.7 days) than the open group. Baker et al. [27] found a high conversion rate in their laparoscopic patients, with a long hospital stay (9.9 ± 7.5 days) that did not differ from the open cases. However, other studies have demonstrated relatively shorter hospital stays after a laparoscopic right hemicolectomy than after an open right hemicolectomy. In the present study, the mean possible length of stay was 7.0 ± 1.5 (range, 4 to 12), and the mean observed length of stay was 9.4 ± 3.1 (range, 5 to 24). The observed length of stay is related to the Korean medical insurance system. Usually, the patients do not want to be discharged because the cost of hospitalization is very inexpensive. Thus, the mean possible length of stay of the present study was longer than the results of the COST trial (7 days vs. 5 days).

The mean operation time of 210.8 ± 80.1 minutes (range, 84 to 490 minutes) in the present study is comparable to previously reported operative times, which range from 107 to 208 minutes [28-34]. The mean number of days to 1st gas passing of 3.4 ± 1.0 days, and the mean number of days to soft diet of 6.0 ± 1.5 days in the present study are comparable to previously reported values for the mean number of days to 1st gas passing (2 to 5 days) and the mean number of days to a soft diet (2 to 5 days) [28-34].

Operative morbidity is also an important concern. The Cochrane Review of the short-term benefits of laparoscopic colorectal surgery showed a lower postoperative complication rate in the laparoscopic group than in the conventional group (18.2% vs. 23.0%; relative risk, 0.72; P = 0.02) [27]. The overall complication rate was 19.2% in the present study. However, in the present study, the complications were mostly mild complications, severe complications being rare. During the first 30 days, no mortalities were noted. Moreover, in this study, complications after 30 days occurred in 4 cases with intestinal obstruction, and the readmission rate was 4.5%. Senagore et al. [35] reported that their 30-day readmission rate was 7% in a study in which 70 cases of laparoscopic right hemicolectomies were evaluated.

In the COST, colon cancer laparoscopic or open resection (COLOR) and CLASICC trials [7-9], the conversion rates ranged from 17 to 29%. Other studies reported that the conversion rate for a right hemicolectomy ranged from 0 to 18% [28-34]. In the present study, the conversion rate was 3.2%, and the reasons of conversion were adhesion and intraoperative bleeding. A re-operation was performed in 1 case due to postoperative bleeding.

In conclusion, the short-term clinical outcomes of the present study showed the feasibility of a laparoscopic right hemicolectomy for the treatment of colon cancer. Moreover, the long-term oncologic results were acceptable. The present data support previous randomized prospective clinical trials (COST, MRC CLASSIC trial).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a faculty research grant of Yonsei University College of Medicine (6-2011-0114). The authors acknowledge Mi Sun Park for her dedicated assistance with the manuscript editing.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Fowler DL, White SA. Laparoscopy-assisted sigmoid resection. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1:183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs M, Verdeja JC, Goldstein HS. Minimally invasive colon resection (laparoscopic colectomy) Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1:144–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faynsod M, Stamos MJ, Arnell T, Borden C, Udani S, Vargas H. A case-control study of laparoscopic versus open sigmoid colectomy for diverticulitis. Am Surg. 2000;66:841–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smadja C, Sbai Idrissi M, Tahrat M, Vons C, Bobocescu E, Baillet P, et al. Elective laparoscopic sigmoid colectomy for diverticulitis. Results of a prospective study. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:645–648. doi: 10.1007/s004649901065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung KL, Kwok SP, Lau WY, Meng WC, Lam TY, Kwong KH, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted resection of rectosigmoid carcinoma. Immediate and medium-term results. Arch Surg. 1997;132:761–764. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430310075015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senagore AJ, Duepree HJ, Delaney CP, Dissanaike S, Brady KM, Fazio VW. Cost structure of laparoscopic and open sigmoid colectomy for diverticular disease: similarities and differences. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:485–490. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6225-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleshman J, Sargent DJ, Green E, Anvari M, Stryker SJ, Beart RW, Jr, et al. Laparoscopic colectomy for cancer is not inferior to open surgery based on 5-year data from the COST Study Group trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:655–662. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318155a762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jayne DG, Guillou PJ, Thorpe H, Quirke P, Copeland J, Smith AM, et al. Randomized trial of laparoscopic-assisted resection of colorectal carcinoma: 3-year results of the UK MRC CLASICC Trial Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3061–3068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.7758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.COLOR Study Group. COLOR: a randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic and open resection for colon cancer. Dig Surg. 2000;17:617–622. doi: 10.1159/000051971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jayne DG, Thorpe HC, Copeland J, Quirke P, Brown JM, Guillou PJ. Five-year follow-up of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of laparoscopically assisted versus open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1638–1645. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SH, Park IJ, Joh YG, Hahn KY. Laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer: a prospective analysis of thirty-month follow-up outcomes in 312 patients. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1197–1202. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joh YG, Kim SH, Hahn KY, Lee DK. Laparoscopic resection of colon cancer: early oncologic outcomes. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2004;20:289–295. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park CW, Choi GS, Jun SH. Comparison of recovery of bowel motility after laparoscopic-assisted and open surgery for right colon cancer: a study of gastric emptying by using Sitz-marker(TM) and changes of intraperitoneal temperature. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2004;20:351–357. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim JG. Current status of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2007;50:249–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JE, Joh YG, Yoo SH, Jeong GY, Kim SH, Chung CS, Long-term outcomes. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2011;27:64–70. doi: 10.3393/jksc.2011.27.2.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim NK, Kang J. Optimal total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: the role of robotic surgery from an expert's view. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2010;26:377–387. doi: 10.3393/jksc.2010.26.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owens WD, Felts JA, Spitznagel EL., Jr ASA physical status classifications: a study of consistency of ratings. Anesthesiology. 1978;49:239–243. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197810000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG. The accordion severity grading system of surgical complications. Ann Surg. 2009;250:177–186. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181afde41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greene FL American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC cancer staging manual. 6th ed. New York: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Washington: NCCN; c2012. [cited 2012 Feb 6]. NCCN practice guidelines in oncology - V.2. 2009. Rectal cancer [Internet] Available from: http://www.ccchina.net/UserFiles/2009-4/20/20094200133667.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edge SB American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marusch F, Gastinger I, Schneider C, Scheidbach H, Konradt J, Bruch HP, et al. Importance of conversion for results obtained with laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:207–214. doi: 10.1007/BF02234294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstein NS, Sanford W, Coffey M, Layfield LJ. Lymph node recovery from colorectal resection specimens removed for adenocarcinoma. Trends over time and a recommendation for a minimum number of lymph nodes to be recovered. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;106:209–216. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/106.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tekkis PP, Smith JJ, Heriot AG, Darzi AW, Thompson MR, Stamatakis JD, et al. A national study on lymph node retrieval in resectional surgery for colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1673–1683. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0691-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braga M, Frasson M, Vignali A, Zuliani W, Civelli V, Di Carlo V. Laparoscopic vs. open colectomy in cancer patients: long-term complications, quality of life, and survival. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:2217–2223. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng MH, Feng B, Lu AG, Li JW, Wang ML, Mao ZH, et al. Laparoscopic versus open right hemicolectomy with curative intent for colon carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:323–326. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i3.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baker RP, Titu LV, Hartley JE, Lee PW, Monson JR. A case-control study of laparoscopic right hemicolectomy vs. open right hemicolectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1675–1679. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0655-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bokey EL, Moore JW, Chapuis PH, Newland RC. Morbidity and mortality following laparoscopic-assisted right hemicolectomy for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(10 Suppl):S24–S28. doi: 10.1007/BF02053802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng SS, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Li JC, Leung WW, Leung KL. Emergency laparoscopic-assisted versus open right hemicolectomy for obstructing right-sided colonic carcinoma: a comparative study of short-term clinical outcomes. World J Surg. 2008;32:454–458. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tong DK, Law WL. Laparoscopic versus open right hemicolectomy for carcinoma of the colon. JSLS. 2007;11:76–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leung KL, Meng WC, Lee JF, Thung KH, Lai PB, Lau WY. Laparoscopic-assisted resection of right-sided colonic carcinoma: a case-control study. J Surg Oncol. 1999;71:97–100. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199906)71:2<97::aid-jso7>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braga M, Frasson M, Vignali A, Zuliani W, Di Carlo V. Open right colectomy is still effective compared to laparoscopy: results of a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:1010–1014. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815c4065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung CC, Ng DC, Tsang WW, Tang WL, Yau KK, Cheung HY, et al. Hand-assisted laparoscopic versus open right colectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:728–733. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318123fbdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lohsiriwat V, Lohsiriwat D, Chinswangwatanakul V, Akaraviputh T, Lert-Akyamanee N. Comparison of short-term outcomes between laparoscopically-assisted vs. transverse-incision open right hemicolectomy for right-sided colon cancer: a retrospective study. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:49. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senagore AJ, Delaney CP, Brady KM, Fazio VW. Standardized approach to laparoscopic right colectomy: outcomes in 70 consecutive cases. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:675–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]