Abstract

Genetic studies on PARK genes have identified dysfunction in proteasomal, lysosomal, and mitochondrial enzymes as pathogenic for Parkinson’s disease (PD). We review the role of these and similar enzymes in mediating innate immune signaling. In particular, we have identified that a number of PARK gene products as well as other enzymes have roles in innate immune signaling as well as DNA repair and regulation, ubiquitination, mitochondrial functioning, and synaptic trafficking. PD enzymatic dysfunction is likely to contribute to inadequate innate immune responses to a variety of extra- and intra-cellular stimuli, with a number of the innate immunity related enzymes found in the characteristic Lewy body pathology of PD. The decrease in innate immunity in PD is associated with an increase in markers of adaptive immunity, and recent GWAS studies have identified variants in human leukocyte antigen region as associated with late-onset sporadic PD (Hamza et al., 2010; Hill-Burns et al., 2011). Intriguing new data also suggest that peripheral immune responses may be involved, giving some potential to alleviate such peripheral dysfunction more directly in patients with PD. It is now important to identify the cell type specific immune responses contributing to the initial changes that occur in PD, as well as to the propagating immune responses important for the progression of PD pathology between cells and within the brain. Overall, a complex interplay between different types of immunity appear to be involved in the underlying pathology of PD.

Keywords: immunity, mitochondrial dysfunction, Parkinson’s disease, synapse dysfunction, ubiquitination

Introduction

Although Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the most common progressive movement disorder in the elderly, there is still considerable uncertainty about its etiology. Recent advances in genetics have identified a number of PARK genes in families with PD, which have pointed to common underlying intrinsically driven intracellular pathways (Corti et al., 2011). These include dysfunction of the proteosome (McNaught et al., 2001), lysosome (Shin et al., 2005), and mitochondria (Muqit et al., 2006). In particular, leucine repeat rich kinase 2 (LRRK2, PARK8) and PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1, PARK6) are linked to familial dominant and recessive PD respectively. PINK1 deletion causes aberrant expression of genes that regulate innate immune responses (Akundi et al., 2011). LRRK2 expression is enriched in human immune cells and is a target gene of IFN-γ (Gardet et al., 2010). Increased LRRK2 expression occurs when an immune response is required (see below). As mutations in these proteins cause PD, this suggests that innate immunity may play a more fundamental role in PD. How these systems interact to cause the fundamental pathology of PD (intracellular Lewy body inclusions made from fibrilized α-synuclein protein) to occur within affected neurons needs to be addressed.

Despite considerable organelle dysfunction, neuronal death occurs slowly, initially, and selectively targeting certain brainstem regions with a predisposition for the substantia nigra (Fearnley and Lees, 1991). Neuronal death does not occur in isolation, but is accompanied by considerable neuroinflammation (Orr et al., 2002; Wilms et al., 2003) and intrinsically driven glial cell changes (Halliday and Stevens, 2011). These changes include the accumulation of α-synuclein in glia, with many of the PARK gene proteins also concentrating in glia in the human brain (LRRK2, PINK1, DJ-1, parkin; Gandhi et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2008; Halliday and Stevens, 2011; Song et al., 2011). As glia interact most closely with the immune system, we will review how innate immunity is involved in these processes.

The innate immune system is an immediate, non-specific, first line of defense against pathogen invasion, contrasting with the delayed and targeted adaptive immune response (Stone et al., 2009). The specific molecular structure of pathogens (pathogen-associated molecular patterns or PAMPs), like lipopolysaccharides (LPS) or the bacterial DNA motif polycytosine guanine (CpG), are directly recognized by phagocytes, granulocytes, and natural killer cells of the immune system (West et al., 2006). These PAMPs bind to Toll-like receptors (TLR) on cells, triggering a cascade of signaling that results in pro-inflammatory cytokine release and complement activation to clear the pathogen or the infected/dead cell through macroautophagy (West et al., 2006).

Pathogens activate cells by binding to specific TLRs through characteristic extracellular multiple leucine-rich repeats domains of TLR (Nguyen et al., 2002). The ultimate induction of interferons and inflammatory cytokines by different pathogens is led by several phosphorylation and subsequent ubiquitination events, with activation of TBK-1 and IKKε, JNK and p38 kinase, IKK, MAPK and MAPKK, IRAK, and TAK1 [detailed in previous reviews (Kawai and Akira, 2006; Seth et al., 2006)]. A major pathway is NF-κB activation by its release from IκB allowing its nuclear translocation and the subsequent activation of target genes to occur. IκB release occurs following IκB phosphorylation and consequent degradation through the lysine 48 linked ubiquitin–proteasome system (Silverman and Maniatis, 2001; Wu et al., 2006).

Innate immunity and PD

Classic PD is not considered an immune disease like multiple sclerosis, and can not be associated with common infectious agents. However, Parkinsonian symptoms can occur after Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) encephalitic infection in patients, with EBV DNA detected in the brain (Espay and Henderson, 2011). This shows that an immune activation in the brain can produce PD-like symptoms, and a number of genetic studies suggest the immune system is commonly involved. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) show that common variants in human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region are associated with late-onset sporadic PD (Hamza et al., 2010; Hill-Burns et al., 2011). The brains of individuals with PD show upregulation of HLA-DR antigens and the presence of HLA-DR-immunopositive and highly reactive microglia (McGeer et al., 1988). Microglia are the only cells in the substantia nigra that express the initial recognition component of the complement cascade, C1q (Carlsson et al., 2011). Finally, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs reduce PD risk (Wahner et al., 2007; Steurer, 2011), further supporting some involvement of the immune system in PD.

From a PARK gene perspective, it is of interest that both parkin (PARK2) and LRRK2 (PARK8) are genes associated with leprosy (Cardoso et al., 2011), which is a chronic infectious disease of peripheral nerves. LRRK2 is also a risk gene for inflammatory bowel disease (Van Limbergen et al., 2009; Torkvist et al., 2010; Umeno et al., 2011), and there is much discussion about PD being initiated from peripheral neurons within the gut (enteric nervous system; Braak et al., 2003). In an animal model of ulcerative colitis, there is an alteration of the blood–brain-barrier (BBB) permeability that leads to more substantive cell loss to pathogen-induced cell loss of the substantia nigra (Villaran et al., 2010). Interestingly, treatment of the ulcerative colitis ameliorated cell loss in the brain in this model (Villaran et al., 2010). This could suggest a more direct link between immune defense mechanisms in peripheral neurons and the later onset of PD. Deletions within PINK1 (PARK6) or DJ-1 (PARK7) genes cause aberrant expression of genes involved in the p38 MAP kinase/NF-κB signaling pathway causing changes in the regulation of the innate immune response (Cornejo Castro et al., 2010; Akundi et al., 2011). This suggests that many PARK genes also have significant influence on the immune system which may be important for the onset and/or progression of PD.

A number of animal models of the neuronal loss in PD use direct initiation of the innate immune system to model this aspect of PD. Administration of LPS induces dramatic cell loss in primary neuronal cultures and direct injection of LPS into the substantia nigra produces progressive nigrostriatal degeneration and movement abnormalities in animal models of PD (Liu, 2006; Dutta et al., 2008). These LPS PD models trigger TLR4 mediated signaling pathways (Carvey et al., 2003; Visintin et al., 2003). Even intraperitoneal and in utero injections of LPS cause degeneration of the nigrostriatal system (Ling et al., 2002; Perry, 2004), consistent with peripheral effects causing PD-like neurodegeneration. These innate immunity models of PD cause neurodegeneration and microglial activation in a time and LPS dose dependent manner (Liu, 2006; Dutta et al., 2008). Similar direct injections of TLR3 into the substantia nigra produce nigrostriatal degeneration (Deleidi et al., 2010). These studies show that strong stimulators of the innate immune system and increased numbers of innate immune receptors can produce significant site-specific neurodegeneration, perhaps suggesting that the nigrostriatal system is particularly vulnerable to immune activation.

Innate immune signaling also plays a role in the abnormal deposition of α-synuclein. In α-synuclein overexpressing models, ablation of TLR4 augments the deposition of α-synculein due to disruption of the ability of microglia to adequately phagocytose α-synuclein (Stefanova et al., 2011). This suggests that certain aspects of innate immunity are required for initial protection from excessive extracellular α-synuclein. Whether these mechanisms play a role in patients is more difficult to determine. Overall, these studies suggest that the innate immune system can play both neuroprotective and neurotoxic roles depending on the circumstances.

Adaptive immunity and PD

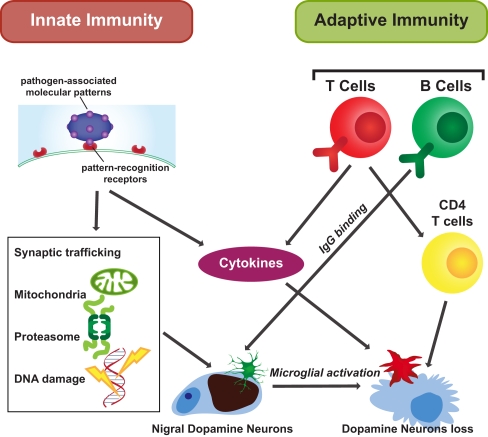

In contrast to the “non-specific” innate immune system, the adaptive immune response is cell mediated and highly specialized to remove a specific antigen. It is mainly composed of two parts: humoral immunity, which is mediated by B-lymphocytes, and cell mediated immunity, which is mediated by T-lymphocytes. The CNS was traditionally considered as an “immune privileged” site due to its protection by the BBB, which prevents toxins and infections from reaching the CNS. However, in PD the BBB is disrupted due to activated microglia and monocytes in PD brain (Stone et al., 2009). IgG, but not IgM, has been shown bound to dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra of idiopathic and familial PD patients, but not in age-matched controls (Orr et al., 2005). In addition, LRRK2, a causative gene for PD (see above), regulates B2-lymphocyte function (Kubo et al., 2010). This suggests that adaptive immunity may also be involved in the progression of PD (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Innate and adaptive immunity in PD. Innate and adaptive immunity are both thought to affect the cellular response to PD. Both produce cytokines facilitating microglial activation. Innate immune signaling is initiated by PAMP binding. Innate immunity influences cell functions through different organelles, such as the nucleus to affect DNA, the mitochondria and proteasome, and through impacting on synaptic trafficking. Adaptive immunity is a subsequent response. Antigen specific adaptive immune processes occur as immune cells survey the brain. In response to stimuli, B cells secrete IgG and CD4 T cells are activated impacting on selective neuronal degeneration.

Apart from B-lymphocyte involvement in PD, both CD4+and CD8+ T-lymphocytes have been found in the SN of PD patients, and CD4+ T-lymphocytes are responsible for the T-cell-mediated immunopathology (Brochard et al., 2009). The expression of CD95 ligand (Fas) has been shown to be important for the capacity of T-lymphocytes to induce neuronal death (Brochard et al., 2009). T-lymphocyte cells and T cell receptor (TCR) associated CD3, a polypeptide complex comprised of four distinct chains (CD3γ, CD3δ, CD3ε, and CD3ζ), are found in the PD characteristic Lewy body lesions (Castellani et al., 2011), providing another direct link between cell mediated immunity and PD pathology (Figure 1).

Through activation of both the adaptive and innate immune systems, cytokines are induced and secreted. Circulating IL-12 and IL-10 are significantly elevated in PD patients compared with controls (Rentzos et al., 2009) and our data show that the protein levels of IL-10 and GM-CSF are elevated in the cortex of patients with PD (unpublished data). Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1)-positive glia are increased in the substantia nigra of PD brains (Miklossy et al., 2006). Further analysis of these immune responses in the brains of patients with PD may provide more specific cytokine targets for modifying detrimental immune responses in PD.

Innate immunity and DNA repair and regulation in PD

The presence of genomic DNA single and double-strand breaks is very common in PD affected brain regions (Hegde et al., 2006). At early stages of DNA damage, DNA sensing molecules (such as PARP and ATM) activate and cause a signaling cascade for repair (Herceg and Wang, 2001). Histone deacetylases (HDAC) are important suppressors of gene transcription, but also deacetylates the p62 subunit of NF-κB increasing its binding to IκB and suppressing innate immunity and interferon-stimulated transcription (Babic et al., 2004; Into et al., 2010). HDACs have been localized to Lewy bodies in patients with PD (Takahashi-Fujigasaki and Fujigasaki, 2006), indicating that they are involved in PD pathogenesis. Inhibiting HDAC alleviates dopamine depletion in models of PD (Outeiro et al., 2007) and is protective by enhancing α-synuclein expression in neurons (Nusinzon and Horvath, 2003; Leng and Chuang, 2006), possibly in concert with an increased innate immune response.

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase catalyzes the attachment of ADP ribose units from NAD to nuclear proteins after DNA damage, resulting in three major outcomes, DNA repair, activation of transcription factors (notably NF-κB), and/or cell death due to NAD depletion and release of apoptosis releasing factor from mitochondria (Kauppinen and Swanson, 2007). PARP negatively regulates α-synuclein expression by binding to the α-synuclein promoter Rep1 region (Chiba-Falek et al., 2005) and α-synuclein protein suppresses PARP activity (Adamczyk and Kazmierczak, 2009). Inhibition of PARP activation protects mice from MPTP-induced parkinsonism (Mandir et al., 1999; Leng and Chuang, 2006). PARP may protect against PD through increasing innate immune signaling.

ATM is a kinase that is recruited to phosphorylate histones for DNA repair, signaling molecules for cell cycle arrest or apoptosis, and nuclear IKKγ (NF-κB essential modulator; Habraken and Piette, 2006; Hinz et al., 2010; Hadian and Krappmann, 2011). Phosphorylation of IKKγ leads to its ubiquitination and cytoplasmic translocation where it associates with the rest of the IKK complex, resulting in IKK activation followed by subsequent NF-κB activation and inflammatory cytokines production (Chen, 2005). ATM has also recently been shown to regulate proteasome-mediated protein turnover through suppression of the ISG15 pathway (Wood et al., 2011). ISG15 is an interferon-stimulated gene activated by viral infection and important in antiviral defense and innate immunity (Skaug and Chen, 2010). It is a ubiquitin-like protein that can be attached to both host and viral proteins (Skaug and Chen, 2010). ATM-deficient mice exhibit a selective loss of dopamine nigrostriatal neurons (Eilam et al., 1998), implicating dysfunction of ubiquitination as a factor in PD neurodegeneration, and specifically of ubiquitination in the innate immune system.

Innate immunity and ubiquitination in PD

The expression of ISG15 is increased in Crohn’s disease (Labbe et al., 2011), an inflammatory bowel disorder sharing common genetic and environmental risk factors with PD (Bihari and Lees, 1987; Bialecka et al., 2007). Both ISG15 and LRRK2 (PARK8) are targets of interferon regulation (Figure 2). Interferon also regulates proteasome processing of ubiquitinated protein degradation into small peptides (Rivett et al., 2001; Piccinini et al., 2003; Figure 2). Ubiquitin is a small molecule and through lysine 48 and lysine 63 forms polyubiquitin chains for protein degradation and cellular localization (Ikeda and Dikic, 2008).

Figure 2.

Innate immunity and the ubiquitin–proteasome system in PD. Innate immunity is used by the cell to increase proteasome degradation of unwanted proteins by direct and indirect stimulation of the protesome through interferon-γ and ISG15, a ubiquitin-like protein that can be attached to both host and viral proteins. ATM (and appropriately functioning LRRK2) usually stimulates innate immune signaling when necessary. However, ATM also regulates proteasome-mediated protein turnover through suppression of the ISG15 pathway, and together with dysfunctional LRRK2 could decrease proteasome activity necessary for an adequate immune response and the degradation of normal cellular protein substrates, like dimer or tetramer forms of α-synuclein. As these forms are normally degraded through the ubiquitin/proteasome and lysosome/autophagy pathways, along with other cellular substrates, dysfunction in these pathways would increase α-synuclein to form toxic oligomeric species that also inhibit the proteasome and autophagy pathways, as well as innate immunity. This scenario would lead to the increase in toxic oligomers of α-synuclein that aggregate into fibrils to form Lewy bodies over time.

Among PARK genes, parkin has a variety of functions. It not only promotes lysine 48 linked ubiquitination for substrate degradation via the proteasome, but also functions in lysine 63 ubiquitin chain assembly to regulate diverse cellular processes, such as ribosome control, protein sorting and trafficking, and endocytosis of membrane proteins (Doss-Pepe et al., 2005). Lysine 63 linked ubiquitin chains promote the degradation of membrane proteins by the lysosome (Doss-Pepe et al., 2005). It is notable that α-synuclein is degraded via both the proteasome and lysosome pathways (Shin et al., 2005), suggestive that lysine 48 and lysine 63 linked ubiquitin chains are both important in the pathogenesis of PD (Figure 2). UCH-L1 has two opposing enzymatic activities, deubiquitination and ubiquityl ligase. The UCH-L1 ligase activity forms lysine 63 linked polyubiquitin chains (Liu et al., 2002). Lysine 63 multiubiquitin chains are also stimulated by α-synuclein (Doss-Pepe et al., 2005), and α-synuclein filaments and oligomers or its mutants inhibit proteasome function (Tanaka et al., 2001; Lindersson et al., 2004). These three genetically linked PD proteins all contribute to lysine 63 multiubiquitin chain formation. Dysfunction of this system is likely to decrease innate immune responses in PD.

Both lysine 48 and lysine 63 linked ubiquitin chains are known to be involved in anti-pathogen signaling cascades. In particular, lysine 63 linked ubiquitination is essential for NF-κB activation (detailed in review of Wu et al., 2006). Phosphorylation of IκB that releases NF-κB only occurs when the kinase IKKβ is released from its complex following IKKγ phosphorylation and lysine 63 linked degradation. Some other key immune response signaling molecules, such as TRAF6, also function as the lysine 63 linked ubiquitin E3 ligase to activate kinase activity (Kawai and Akira, 2006), and TRAF5 has been identified as a downstream target of VISA (see below) that mediates both IRF-3 and NF-κB activation (Tang and Wang, 2010).

Innate immunity and mitochondrial function in PD

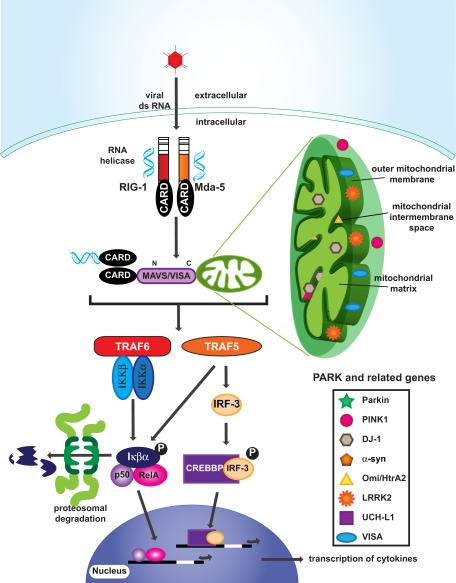

The proper functioning of mitochondria is crucial for adequate innate immune defense (Qi et al., 2007; Tang and Wang, 2010; West et al., 2011). Intracellular double-stranded RNA originating from viruses or virus replication is recognized by RIG-I and Mda5, which contain a caspase recruitment domain (CARD; Figure 3). Activated RIG-I/Mda5 passes the signal to mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS/VISA) proteins via a CARD–CARD domain interaction (Figure 3). The C-terminal of MAVS/VISA bind to mitochondria to activate NF-κB and start interferon α and β production (Qi et al., 2007; Figure 3). Upon viral infection, MAVS/VISA immigrate from the outer membrane into the mitochondrial detergent-resistant membrane fraction, suggesting that mitochondria react and contribute to antiviral signaling (Qi et al., 2007; Figure 3). In addition to regulating antiviral signaling, there is mounting evidence that mitochondria facilitate antibacterial immunity by generating reactive oxygen species and contributing to innate immune activation following cellular damage and stress (Nakahira et al., 2011).

Figure 3.

Innate immunity and mitochondria in PD. Many PARK related gene products are located in mitochondria, implicating mitochondrial dysfunction in PD. Interestingly, MAVS/VISA that are attached to the outer membrane of mitochondria are involved in viral infection signaling by activating TRAF6 and TRAF5. Phosphorylation of Iκβα and IRF-3 leads to nuclear translocation of transcription factors and the production of cytokines.

Most nuclear encoded PARK gene products are located within mitochondria (Table 1), such as PINK1, DJ-1, Omi/HtrA2, and LRRK2, suggesting mitochondrial dysfunction is common in PD. The mitochondrial complex I has been shown to be selectively reduced in PD vulnerable regions, such as the substantia nigra (Schapira et al., 1989). The mitochondrial complex I inhibitor rotenone and mitochondrial toxin MPTP (1-methyl 4-phenyl 1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) induce selective dopamine neuron loss and a parkinsonian syndrome and have been used as a major model for studying the tissue aspects of PD (Langston and Ballard, 1984; Betarbet et al., 2000). These changes may decrease the cellular responses of the innate immune system in PD.

Table 1.

Cellular localization and functions PARK and related genes.

| Cellular location indicative functions in mitochondria and synaptic trafficking | Ubiquitination | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parkin | Outer mitochondrial membrane Synaptic vesicles and the synaptic membrane | Lysine 48-, 63-linked ubiquitin E3 ligase | Kubo et al. (2001); Darios et al. (2003) |

| DJ-1 | Mitochondrial matrix and inter-membrane space | NA | Zhang et al., 2005) |

| PINK1 | Mitochondria | Upstream of parkin | Valente et al. (2004) |

| Omi/HtrA2 | Mitochondrial inter-membrane space | NA | Strauss et al. (2005) |

| LRRK2 | Outer mitochondrial membrane | NA | West et al. (2005) |

| α-synuclein | Presynaptic terminal | Promote 63 linked ubiquitin assemble | Iwai et al. (1995) |

| UCH-L1 | Synaptic vesicle | Lysine 63 linked ubiquitin E3 ligase | Liu et al. (2002) |

| VISA | Outer mitochondrial membrane | NA | Seth et al. (2005) |

NA, not available.

Innate immunity and synaptic trafficking in PD

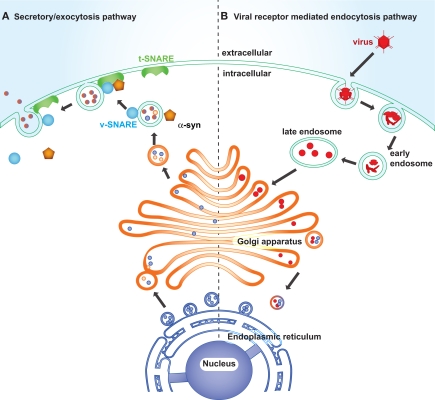

Most enveloped animal RNA and DNA viruses enter host cells via receptor-medicated endocytosis or viral membrane fusion with the plasma membrane in order to replicate. Endocytosis impinges on viral infection at a number of different cellular levels, from the plasma membrane to endosome to lysosome or alternatively to Golgi, and to ER (Figure 4; Hacker et al., 1998; Leadbetter et al., 2002; Diebold et al., 2004). Viral proteins accumulate in the ER during viral replication and elicit ER stress. Viral replication induced ER stress disturbs vesicle trafficking within the intracellular membranous web (Goodridge et al., 2011).

Figure 4.

Synaptic trafficking failure and viral intake leading to synaptic dysfunction in PD. Left: The endoplasmic reticulum is composed of a membranous network of tubes and cisternae enclosed in a membrane. It is continuous with the membrane surrounding the nuclear membrane and connects with the Golgi network via the vesicles carrying newly synthesized proteins. Certain vesicle-trafficking steps are required for the translocation of a vesicle from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane. A transport vesicle is tethered and docked at the target membrane to form a tight SNARE complex, thus to merge the vesicle membrane with the target membrane and evacuate neurotransmitters into the extracellular space. The vesicle releasing process is under the assistance of α-synuclein, CDCrel-1, and synaptotagmin. Right: Viruses enter host cells through endosomes. Late endosomes fuse with or convert to lysosomes to degrade its contents, or alternatively it forms budding vesicles that pass to the trans-Golgi region and translocate to the Golgi and endoplasmic reticulum. The endoplasmic reticulum is coated with ribosomes, which assemble the viral amino acids into viral proteins.

Many PARK genes are associated with endocytosis and synaptic vesicle trafficking. α-Synuclein, parkin and UCH-L1 concentrate in the presynapse and associate with synaptic vesicles, anchoring and regulating the undocked pool of presynaptic vesicles (Di Rosa et al., 2003; Ferrer, 2009). α-Synuclein acts as a molecular chaperone, assisting in the folding and refolding of synaptic proteins called SNAREs, which are crucial for the release of neurotransmitters at the neuronal synapse, vesicle recycling, and synaptic integrity (Chandra et al., 2005). Upon the arrival of action potentials at the synaptic terminal, SNARE complexes, assembly of vesicle membrane (v-SNARE) and the presynaptic plasma membrane (t-SNARE), fuse the vesicle at the plasma membrane to release neurotransmitter into the synaptic cleft (Chandra et al., 2005; Fortin et al., 2005). Parkin ubiquitinates and regulates the turnover of the synaptic vesicle-associated protein, CDCrel-1, a synaptic vesicle-enriched septin GTPase implicated in the inhibition of exocytosis through its interactions with the SNARE complex component, syntaxin (Zhang et al., 2000). Another substrate of parkin is synaptotagmin XI, a member of the synaptotagmin family that is well characterized in vesicle formation and docking by interaction with SNAREs (Huynh et al., 2003). Loss of function of α-synuclein, parkin, or DJ-1 reduces neurotransmission and synaptic vesicle trafficking (Abeliovich et al., 2000; Goldberg et al., 2005). UCH-L1 deficient mice also show altered vesicle transport gene expression (Bonin et al., 2004). Reduced innate immunity allowing for pathogen replication would significantly exacerbate any loss of synaptic function caused by PARK gene products (Figure 4) precipitating frank degeneration.

Conclusion

A number of intrinsically driven cellular pathways shown to be dysfunctional in PD are important in mediating innate immune signaling. These important intracellular pathways have been identified through genetic studies in patients with PD. More recent genetic studies have also implicated immune pathways in the pathogenesis of PD. In particular, we have identified a number of PARK gene products as well as other enzymes that have dual roles in innate immune signaling as well as proteasome, lysosome, and mitochondrial functioning. The additional enzymes identified are important for DNA repair and regulation, ubiquitination, mitochondrial function, and synaptic trafficking. These pathways appear to lose their ability to mount an adequate innate immune response to PD and experimental manipulation of many of these intracellular molecules has been associated with characteristic PD pathologies in animal models. Intriguing new data also suggest that peripheral immune responses may be involved, with the potential to alleviate such peripheral dysfunction more directly in patients with PD.

Most important, the molecular pathways involved are likely to function in a cell type specific manner (Ledesma et al., 2002), a concept that has not yet been evaluated substantially in patients with PD. The cross-talk between neurons and glia is crucial for an adequate immune response, with astrocytes considered particularly important (Halliday and Stevens, 2011; Schmidt et al., 2011). Astrocytic endfeet form part of the BBB and may serve as ideal sentinel cells able to sense the appearance of toxins and viral pathogens (Scumpia et al., 2005), similar to their cousins found in the gut (Savidge et al., 2007; Daneman and Rescigno, 2009). Astroglia in both the brain and gut regulate barrier function and membrane permeability (Savidge et al., 2007; Daneman and Rescigno, 2009), functions which may be important for the cell to cell transfer of α-synuclein pathology as well as more traditional infectious agents. The increased expression of PARK gene proteins in astrocytes (see above) and their lack of activation to PD pathology in patients (Mirza et al., 2000; Halliday and Stevens, 2011) lends weight to a loss of innate immunity and BBB function in PD that potentially increases membrane and cellular permeability leading to increased toxin and pathogen infiltration in the brain. In addition to the direct cellular damage to vulnerable neurons this would initiate, pathogen exposure may also activate the alternate adaptive immune responses that are thought to participate in propagating the pathology of PD.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Heidi Cartwight for the figurework. Yue Huang is funded by a University of New South Wales Goldstar award. Glenda M. Halliday is funded as a Senior Principal Research Fellow of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Abbreviations

CARD, caspase recruitment domain; CpG, polycytosine guanine; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; HDAC, histone deacetylase; IKK, IκB kinase; IRAK, interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; LPS, lipopolysaccharides; LRRK2, leucine-rich repeat kinase 2; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MAPKK, MAPK kinase; MAVS, mitochondrial antiviral signaling; Mda5, melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5; MPTP, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine; PAMPs, pathogen-associated molecular pattern; PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase; PD, Parkinson’s disease; PINK1, PTEN-induced putative kinase 1; PKR, Protein kinase RNA-activated; RIG-I, RNA helicases protein retinoic acid-inducible gene I protein; TAK1, Transforming growth factor-beta-activated kinase 1; TBK-1, TANK-binding kinase 1; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TRAF6, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6.

References

- Abeliovich A., Schmitz Y., Farinas I., Choi-Lundberg D., Ho W. H., Castillo P. E., Shinsky N., Verdugo J. M., Armanini M., Ryan A., Hynes M., Phillips H., Sulzer D., Rosenthal A. (2000). Mice lacking alpha-synuclein display functional deficits in the nigrostriatal dopamine system. Neuron 25, 239–252 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80886-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamczyk A., Kazmierczak A. (2009). Alpha-synuclein inhibits poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) activity via NO-dependent pathway. Folia Neuropathol. 47, 247–251 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akundi R. S., Huang Z., Eason J., Pandya J. D., Zhi L., Cass W. A., Sullivan P. G., Bueler H. (2011). Increased mitochondrial calcium sensitivity and abnormal expression of innate immunity genes precede dopaminergic defects in Pink1-deficient mice. PLoS ONE 6, e16038. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babic I., Jakymiw A., Fujita D. J. (2004). The RNA binding protein Sam68 is acetylated in tumor cell lines, and its acetylation correlates with enhanced RNA binding activity. Oncogene 23, 3781–3789 10.1038/sj.onc.1207484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betarbet R., Sherer T. B., Mackenzie G., Garcia-Osuna M., Panov A. V., Greenamyre J. T. (2000). Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 1301–1306 10.1038/81834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialecka M., Kurzawski M., Klodowska-Duda G., Opala G., Juzwiak S., Kurzawski G., Tan E. K., Drozdzik M. (2007). CARD15 variants in patients with sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Res. 57, 473–476 10.1016/j.neures.2006.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bihari K., Lees A. J. (1987). Cigarette smoking, Parkinson’s disease and ulcerative colitis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 50, 635. 10.1136/jnnp.50.5.635-a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonin M., Poths S., Osaka H., Wang Y. L., Wada K., Riess O. (2004). Microarray expression analysis of gad mice implicates involvement of Parkinson’s disease associated UCH-L1 in multiple metabolic pathways. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 126, 88–97 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Rub U., Gai W. P., Del Tredici K. (2003). Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: possible routes by which vulnerable neuronal types may be subject to neuroinvasion by an unknown pathogen. J. Neural Transm. 110, 517–536 10.1007/s00702-002-0808-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brochard V., Combadiere B., Prigent A., Laouar Y., Perrin A., Beray-Berthat V., Bonduelle O., Alvarez-Fischer D., Callebert J., Launay J. M., Duyckaerts C., Flavell R. A., Hirsch E. C., Hunot S. (2009). Infiltration of CD4+ lymphocytes into the brain contributes to neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Parkinson disease. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 182–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso C. C., Pereira A. C., De Sales Marques C., Moraes M. O. (2011). Leprosy susceptibility: genetic variations regulate innate and adaptive immunity, and disease outcome. Future Microbiol. 6, 533–549 10.2217/fmb.11.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson T., Schindler F. R., Hollerhage M., Depboylu C., Arias-Carrion O., Schnurrbusch S., Rosler T. W., Wozny W., Schwall G. P., Groebe K., Oertel W. H., Brundin P., Schrattenholz A., Hoglinger G. U. (2011). Systemic administration of neuregulin-1beta1 protects dopaminergic neurons in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 117, 1066–1074 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07284.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvey P. M., Chang Q., Lipton J. W., Ling Z. (2003). Prenatal exposure to the bacteriotoxin lipopolysaccharide leads to long-term losses of dopamine neurons in offspring: a potential, new model of Parkinson’s disease. Front. Biosci. 8, s826–s837 10.2741/1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani R. J., Nugent S. L., Morrison A. L., Zhu X., Lee H. G., Harris P. L., Bajic V., Sharma H. S., Chen S. G., Oettgen P., Perry G., Smith M. A. (2011). CD3 in Lewy pathology: does the abnormal recall of neurodevelopmental processes underlie Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 118, 23–26 10.1007/s00702-010-0485-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S., Gallardo G., Fernandez-Chacon R., Schluter O. M., Sudhof T. C. (2005). Alpha-synuclein cooperates with CSPalpha in preventing neurodegeneration. Cell 123, 383–396 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. J. (2005). Ubiquitin signalling in the NF-kappaB pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 758–765 10.1038/ncb1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba-Falek O., Kowalak J. A., Smulson M. E., Nussbaum R. L. (2005). Regulation of alpha-synuclein expression by poly (ADP ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) binding to the NACP-Rep1 polymorphic site upstream of the SNCA gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76, 478–492 10.1086/428655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo Castro E. M., Waak J., Weber S. S., Fiesel F. C., Oberhettinger P., Schutz M., Autenrieth I. B., Springer W., Kahle P. J. (2010). Parkinson’s disease-associated DJ-1 modulates innate immunity signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neural Transm. 117, 599–604 10.1007/s00702-010-0397-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti O., Lesage S., Brice A. (2011). What genetics tells us about the causes and mechanisms of Parkinson’s disease. Physiol. Rev. 91, 1161–1218 10.1152/physrev.00022.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman R., Rescigno M. (2009). The gut immune barrier and the blood-brain barrier: are they so different? Immunity 31, 722–735 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darios F., Corti O., Lucking C. B., Hampe C., Muriel M. P., Abbas N., Gu W. J., Hirsch E. C., Rooney T., Ruberg M., Brice A. (2003). Parkin prevents mitochondrial swelling and cytochrome c release in mitochondria-dependent cell death. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 517–526 10.1093/hmg/ddg044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleidi M., Hallett P. J., Koprich J. B., Chung C. Y., Isacson O. (2010). The Toll-like receptor-3 agonist polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid triggers nigrostriatal dopaminergic degeneration. J. Neurosci. 30, 16091–16101 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2400-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Rosa G., Puzzo D., Sant’Angelo A., Trinchese F., Arancio O. (2003). Alpha-synuclein: between synaptic function and dysfunction. Histol. Histopathol. 18, 1257–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diebold S. S., Kaisho T., Hemmi H., Akira S., Reis E Sousa C. (2004). Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science 303, 1529–1531 10.1126/science.1093616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss-Pepe E. W., Chen L., Madura K. (2005). Alpha-synuclein and parkin contribute to the assembly of ubiquitin lysine 63-linked multiubiquitin chains. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 16619–16624 10.1074/jbc.M413591200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta G., Zhang P., Liu B. (2008). The lipopolysaccharide Parkinson’s disease animal model: mechanistic studies and drug discovery. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 22, 453–464 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2008.00616.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilam R., Peter Y., Elson A., Rotman G., Shiloh Y., Groner Y., Segal M. (1998). Selective loss of dopaminergic nigro-striatal neurons in brains of Atm-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 12653–12656 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espay A. J., Henderson K. K. (2011). Postencephalitic parkinsonism and basal ganglia necrosis due to Epstein-Barr virus infection. Neurology 76, 1529–1530 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182143537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnley J. M., Lees A. J. (1991). Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain 114 (Pt 5), 2283–2301 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I. (2009). Early involvement of the cerebral cortex in Parkinson’s disease: convergence of multiple metabolic defects. Prog. Neurobiol. 88, 89–103 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin D. L., Nemani V. M., Voglmaier S. M., Anthony M. D., Ryan T. A., Edwards R. H. (2005). Neural activity controls the synaptic accumulation of alpha-synuclein. J. Neurosci. 25, 10913–10921 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2922-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi S., Muqit M. M., Stanyer L., Healy D. G., Abou-Sleiman P. M., Hargreaves I., Heales S., Ganguly M., Parsons L., Lees A. J., Latchman D. S., Holton J. L., Wood N. W., Revesz T. (2006). PINK1 protein in normal human brain and Parkinson’s disease. Brain 129, 1720–1731 10.1093/brain/awl114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardet A., Benita Y., Li C., Sands B. E., Ballester I., Stevens C., Korzenik J. R., Rioux J. D., Daly M. J., Xavier R. J., Podolsky D. K. (2010). LRRK2 is involved in the IFN-gamma response and host response to pathogens. J. Immunol. 185, 5577–5585 10.4049/jimmunol.1000548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg M. S., Pisani A., Haburcak M., Vortherms T. A., Kitada T., Costa C., Tong Y., Martella G., Tscherter A., Martins A., Bernardi G., Roth B. L., Pothos E. N., Calabresi P., Shen J. (2005). Nigrostriatal dopaminergic deficits and hypokinesia caused by inactivation of the familial Parkinsonism-linked gene DJ-1. Neuron 45, 489–496 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodridge H. S., Reyes C. N., Becker C. A., Katsumoto T. R., Ma J., Wolf A. J., Bose N., Chan A. S., Magee A. S., Danielson M. E., Weiss A., Vasilakos J. P., Underhill D. M. (2011). Activation of the innate immune receptor Dectin-1 upon formation of a ‘phagocytic synapse’. Nature 472, 471–475 10.1038/nature10071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habraken Y., Piette J. (2006). NF-kappaB activation by double-strand breaks. Biochem. Pharmacol. 72, 1132–1141 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker H., Mischak H., Miethke T., Liptay S., Schmid R., Sparwasser T., Heeg K., Lipford G. B., Wagner H. (1998). CpG-DNA-specific activation of antigen-presenting cells requires stress kinase activity and is preceded by non-specific endocytosis and endosomal maturation. EMBO J. 17, 6230–6240 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadian K., Krappmann D. (2011). Signals from the nucleus: activation of NF-kappaB by cytosolic ATM in the DNA damage response. Sci. Signal. 4, pe2. 10.1126/scisignal.2001712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday G. M., Stevens C. H. (2011). Glia: initiators and progressors of pathology in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 26, 6–17 10.1002/mds.23669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza T. H., Zabetian C. P., Tenesa A., Laederach A., Montimurro J., Yearout D., Kay D. M., Doheny K. F., Paschall J., Pugh E., Kusel V. I., Collura R., Roberts J., Griffith A., Samii A., Scott W. K., Nutt J., Factor S. A., Payami H. (2010). Common genetic variation in the HLA region is associated with late-onset sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Genet. 42, 781–785 10.1038/ng.642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde M. L., Gupta V. B., Anitha M., Harikrishna T., Shankar S. K., Muthane U., Subba Rao K., Jagannatha Rao K. S. (2006). Studies on genomic DNA topology and stability in brain regions of Parkinson’s disease. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 449, 143–156 10.1016/j.abb.2006.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herceg Z., Wang Z. Q. (2001). Functions of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) in DNA repair, genomic integrity and cell death. Mutat. Res. 477, 97–110 10.1016/S0027-5107(01)00111-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Burns E. M., Factor S. A., Zabetian C. P., Thomson G., Payami H. (2011). Evidence for more than one Parkinson’s disease-associated variant within the HLA region. PLoS ONE 6, e27109. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz M., Stilmann M., Arslan S. C., Khanna K. K., Dittmar G., Scheidereit C. (2010). A cytoplasmic ATM-TRAF6-cIAP1 module links nuclear DNA damage signaling to ubiquitin-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Mol. Cell 40, 63–74 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Song Y. J., Murphy K., Holton J. L., Lashley T., Revesz T., Gai W. P., Halliday G. M. (2008). LRRK2 and parkin immunoreactivity in multiple system atrophy inclusions. Acta Neuropathol. 116, 639–646 10.1007/s00401-008-0446-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh D. P., Scoles D. R., Nguyen D., Pulst S. M. (2003). The autosomal recessive juvenile Parkinson disease gene product, parkin, interacts with and ubiquitinates synaptotagmin XI. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 2587–2597 10.1093/hmg/ddg175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda F., Dikic I. (2008). Atypical ubiquitin chains: new molecular signals. “Protein Modifications: Beyond the Usual Suspects” review series. EMBO Rep. 9, 536–542 10.1038/embor.2008.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Into T., Inomata M., Niida S., Murakami Y., Shibata K. (2010). Regulation of MyD88 aggregation and the MyD88-dependent signaling pathway by sequestosome 1 and histone deacetylase 6. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 35759–35769 10.1074/jbc.M110.126904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai A., Masliah E., Yoshimoto M., Ge N., Flanagan L., De Silva H. A., Kittel A., Saitoh T. (1995). The precursor protein of non-A beta component of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid is a presynaptic protein of the central nervous system. Neuron 14, 467–475 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90302-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppinen T. M., Swanson R. A. (2007). The role of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in CNS disease. Neuroscience 145, 1267–1272 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.09.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T., Akira S. (2006). Innate immune recognition of viral infection. Nat. Immunol. 7, 131–137 10.1038/nrm1835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo M., Kamiya Y., Nagashima R., Maekawa T., Eshima K., Azuma S., Ohta E., Obata F. (2010). LRRK2 is expressed in B-2 but not in B-1 B cells, and downregulated by cellular activation. J. Neuroimmunol. 229, 123–128 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo S. I., Kitami T., Noda S., Shimura H., Uchiyama Y., Asakawa S., Minoshima S., Shimizu N., Mizuno Y., Hattori N. (2001). Parkin is associated with cellular vesicles. J. Neurochem. 78, 42–54 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00364.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbe C., Boucher G., Foisy S., Alikashani A., Nkwimi H., David G., Beaudoin M., Goyette P., Charron G., Xavier R. J., Rioux J. D. (2011). Genome-wide expression profiling implicates a MAST3-regulated gene set in colonic mucosal inflammation of ulcerative colitis patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis.. 10.1002/ibd.21887 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston J. W., Ballard P. (1984). Parkinsonism induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP): implications for treatment and the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 11, 160–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadbetter E. A., Rifkin I. R., Hohlbaum A. M., Beaudette B. C., Shlomchik M. J., Marshak-Rothstein A. (2002). Chromatin-IgG complexes activate B cells by dual engagement of IgM and Toll-like receptors. Nature 416, 603–607 10.1038/416603a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma M. D., Galvan C., Hellias B., Dotti C., Jensen P. H. (2002). Astrocytic but not neuronal increased expression and redistribution of parkin during unfolded protein stress. J. Neurochem. 83, 1431–1440 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01253.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng Y., Chuang D. M. (2006). Endogenous alpha-synuclein is induced by valproic acid through histone deacetylase inhibition and participates in neuroprotection against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 26, 7502–7512 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0096-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindersson E., Beedholm R., Hojrup P., Moos T., Gai W., Hendil K. B., Jensen P. H. (2004). Proteasomal inhibition by alpha-synuclein filaments and oligomers. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12924–12934 10.1074/jbc.M306390200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Z., Gayle D. A., Ma S. Y., Lipton J. W., Tong C. W., Hong J. S., Carvey P. M. (2002). In utero bacterial endotoxin exposure causes loss of tyrosine hydroxylase neurons in the postnatal rat midbrain. Mov. Disord. 17, 116–124 10.1002/mds.10152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B. (2006). Modulation of microglial pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic activity for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. AAPS J. 8, E606–E621 10.1208/aapsj080367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Fallon L., Lashuel H. A., Liu Z., Lansbury P. T., Jr. (2002). The UCH-L1 gene encodes two opposing enzymatic activities that affect alpha-synuclein degradation and Parkinson’s disease susceptibility. Cell 111, 209–218 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01012-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandir A. S., Przedborski S., Jackson-Lewis V., Wang Z. Q., Simbulan-Rosenthal C. M., Smulson M. E., Hoffman B. E., Guastella D. B., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M. (1999). Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase activation mediates 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced parkinsonism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 5774–5779 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer P. L., Itagaki S., Boyes B. E., McGeer E. G. (1988). Reactive microglia are positive for HLA-DR in the substantia nigra of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease brains. Neurology 38, 1285–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaught K. S., Olanow C. W., Halliwell B., Isacson O., Jenner P. (2001). Failure of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 589–594 10.1038/35086067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklossy J., Doudet D. D., Schwab C., Yu S., Mcgeer E. G., Mcgeer P. L. (2006). Role of ICAM-1 in persisting inflammation in Parkinson disease and MPTP monkeys. Exp. Neurol. 197, 275–283 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza B., Hadberg H., Thomsen P., Moos T. (2000). The absence of reactive astrocytosis is indicative of a unique inflammatory process in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience 95, 425–432 10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00455-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muqit M. M., Gandhi S., Wood N. W. (2006). Mitochondria in Parkinson disease: back in fashion with a little help from genetics. Arch. Neurol. 63, 649–654 10.1001/archneur.63.5.649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahira K., Haspel J. A., Rathinam V. A., Lee S. J., Dolinay T., Lam H. C., Englert J. A., Rabinovitch M., Cernadas M., Kim H. P., Fitzgerald K. A., Ryter S. W., Choi A. M. (2011). Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat. Immunol. 12, 222–230 10.1038/nrm3085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen M. D., Julien J. P., Rivest S. (2002). Innate immunity: the missing link in neuroprotection and neurodegeneration? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 216–227 10.1038/nrn752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusinzon I., Horvath C. M. (2003). Interferon-stimulated transcription and innate antiviral immunity require deacetylase activity and histone deacetylase 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 14742–14747 10.1073/pnas.2433987100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr C. F., Rowe D. B., Halliday G. M. (2002). An inflammatory review of Parkinson’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 68, 325–340 10.1016/S0301-0082(02)00127-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr C. F., Rowe D. B., Mizuno Y., Mori H., Halliday G. M. (2005). A possible role for humoral immunity in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Brain 128, 2665–2674 10.1093/brain/awh625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outeiro T. F., Kontopoulos E., Altmann S. M., Kufareva I., Strathearn K. E., Amore A. M., Volk C. B., Maxwell M. M., Rochet J. C., Mclean P. J., Young A. B., Abagyan R., Feany M. B., Hyman B. T., Kazantsev A. G. (2007). Sirtuin 2 inhibitors rescue alpha-synuclein-mediated toxicity in models of Parkinson’s disease. Science 317, 516–519 10.1126/science.1143780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry V. H. (2004). The influence of systemic inflammation on inflammation in the brain: implications for chronic neurodegenerative disease. Brain Behav. Immun. 18, 407–413 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccinini M., Mostert M., Croce S., Baldovino S., Papotti M., Rinaudo M. T. (2003). Interferon-gamma-inducible subunits are incorporated in human brain 20S proteasome. J. Neuroimmunol. 135, 135–140 10.1016/S0165-5728(02)00439-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi B., Huang Y., Rowe D., Halliday G. (2007). VISA – a pass to innate immunity. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39, 287–291 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentzos M., Nikolaou C., Andreadou E., Paraskevas G. P., Rombos A., Zoga M., Tsoutsou A., Boufidou F., Kapaki E., Vassilopoulos D. (2009). Circulating interleukin-10 and interleukin-12 in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. 119, 332–337 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivett A. J., Bose S., Brooks P., Broadfoot K. I. (2001). Regulation of proteasome complexes by gamma-interferon and phosphorylation. Biochimie 83, 363–366 10.1016/S0300-9084(01)01249-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savidge T. C., Sofroniew M. V., Neunlist M. (2007). Starring roles for astroglia in barrier pathologies of gut and brain. Lab. Invest. 87, 731–736 10.1038/labinvest.3700600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schapira A. H., Cooper J. M., Dexter D., Jenner P., Clark J. B., Marsden C. D. (1989). Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 1, 1269. 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)92366-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S., Linnartz B., Mendritzki S., Sczepan T., Lubbert M., Stichel C. C., Lubbert H. (2011). Genetic mouse models for Parkinson’s disease display severe pathology in glial cell mitochondria. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 1197–1211 10.1093/hmg/ddq564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scumpia P. O., Kelly K. M., Reeves W. H., Stevens B. R. (2005). Double-stranded RNA signals antiviral and inflammatory programs and dysfunctional glutamate transport in TLR3-expressing astrocytes. Glia 52, 153–162 10.1002/glia.20234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth R. B., Sun L., Chen Z. J. (2006). Antiviral innate immunity pathways. Cell Res. 16, 141–147 10.1038/sj.cr.7310019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth R. B., Sun L., Ea C. K., Chen Z. J. (2005). Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-kappaB and IRF 3. Cell 122, 669–682 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin Y., Klucken J., Patterson C., Hyman B. T., Mclean P. J. (2005). The co-chaperone carboxyl terminus of Hsp70-interacting protein (CHIP) mediates alpha-synuclein degradation decisions between proteasomal and lysosomal pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 23727–23734 10.1074/jbc.M503326200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman N., Maniatis T. (2001). NF-kappaB signaling pathways in mammalian and insect innate immunity. Genes Dev. 15, 2321–2342 10.1101/gad.909001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaug B., Chen Z. J. (2010). Emerging role of ISG15 in antiviral immunity. Cell 143, 187–190 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. J., Huang Y., Halliday G. M. (2011). Clinical correlates of similar pathologies in parkinsonian syndromes. Mov. Disord. 26, 499–506 10.1002/mds.23477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanova N., Fellner L., Reindl M., Masliah E., Poewe W., Wenning G. K. (2011). Toll-like receptor 4 promotes alpha-synuclein clearance and survival of nigral dopaminergic neurons. Am. J. Pathol. 179, 954–963 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steurer J. (2011). [Nonsteroidal analgesics have a protective effect against Parkinson disease]. Praxis (Bern 1994) 100, 617–618 10.1024/1661-8157/a000535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone D. K., Reynolds A. D., Mosley R. L., Gendelman H. E. (2009). Innate and adaptive immunity for the pathobiology of Parkinson’s disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 2151–2166 10.1089/ars.2009.2460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss K. M., Martins L. M., Plun-Favreau H., Marx F. P., Kautzmann S., Berg D., Gasser T., Wszolek Z., Muller T., Bornemann A., Wolburg H., Downward J., Riess O., Schulz J. B., Kruger R. (2005). Loss of function mutations in the gene encoding Omi/HtrA2 in Parkinson’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 2099–2111 10.1093/hmg/ddi215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi-Fujigasaki J., Fujigasaki H. (2006). Histone deacetylase (HDAC) 4 involvement in both Lewy and Marinesco bodies. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 32, 562–566 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2005.00705.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y., Engelender S., Igarashi S., Rao R. K., Wanner T., Tanzi R. E., Sawa A., V L. D., Dawson T. M., Ross C. A. (2001). Inducible expression of mutant alpha-synuclein decreases proteasome activity and increases sensitivity to mitochondria-dependent apoptosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 919–926 10.1093/hmg/10.9.919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang E. D., Wang C. Y. (2010). TRAF5 is a downstream target of MAVS in antiviral innate immune signaling. PLoS ONE 5, e9172. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torkvist L., Halfvarson J., Ong R. T., Lordal M., Sjoqvist U., Bresso F., Bjork J., Befrits R., Lofberg R., Blom J., Carlson M., Padyukov L., D’Amato M., Seielstad M., Pettersson S. (2010). Analysis of 39 Crohn’s disease risk loci in Swedish inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 16, 907–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeno J., Asano K., Matsushita T., Matsumoto T., Kiyohara Y., Iida M., Nakamura Y., Kamatani N., Kubo M. (2011). Meta-analysis of published studies identified eight additional common susceptibility loci for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel. Dis. 17, 2407–2415 10.1002/ibd.21651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente E. M., Abou-Sleiman P. M., Caputo V., Muqit M. M., Harvey K., Gispert S., Ali Z., Del Turco D., Bentivoglio A. R., Healy D. G., Albanese A., Nussbaum R., Gonzalez-Maldonado R., Deller T., Salvi S., Cortelli P., Gilks W. P., Latchman D. S., Harvey R. J., Dallapiccola B., Auburger G., Wood N. W. (2004). Hereditary early-onset Parkinson’s disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science 304, 1158–1160 10.1126/science.1096284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Limbergen J., Wilson D. C., Satsangi J. (2009). The genetics of Crohn’s disease. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 10, 89–116 10.1146/annurev-genom-082908-150013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villaran R. F., Espinosa-Oliva A. M., Sarmiento M., De Pablos R. M., Arguelles S., Delgado-Cortes M. J., Sobrino V., Van Rooijen N., Venero J. L., Herrera A. J., Cano J., Machado A. (2010). Ulcerative colitis exacerbates lipopolysaccharide-induced damage to the nigral dopaminergic system: potential risk factor in Parkinson‘s disease. J. Neurochem. 114, 1687–1700 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visintin A., Latz E., Monks B. G., Espevik T., Golenbock D. T. (2003). Lysines 128 and 132 enable lipopolysaccharide binding to MD-2, leading to Toll-like receptor-4 aggregation and signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 48313–48320 10.1074/jbc.M306802200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahner A. D., Bronstein J. M., Bordelon Y. M., Ritz B. (2007). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may protect against Parkinson disease. Neurology 69, 1836–1842 10.1212/01.wnl.0000279519.99344.ad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West A. B., Moore D. J., Biskup S., Bugayenko A., Smith W. W., Ross C. A., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M. (2005). Parkinson’s disease-associated mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 augment kinase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 16842–16847 10.1073/pnas.0507360102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West A. P., Koblansky A. A., Ghosh S. (2006). Recognition and signaling by Toll-like receptors. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 409–437 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.122303.115827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West A. P., Shadel G. S., Ghosh S. (2011). Mitochondria in innate immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 389–402 10.1038/nri2975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilms H., Rosenstiel P., Sievers J., Deuschl G., Zecca L., Lucius R. (2003). Activation of microglia by human neuromelanin is NF-kappaB dependent and involves p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase: implications for Parkinson’s disease. FASEB J. 17, 500–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood L. M., Sankar S., Reed R. E., Haas A. L., Liu L. F., Mckinnon P., Desai S. D. (2011). A novel role for ATM in regulating proteasome-mediated protein degradation through suppression of the ISG15 conjugation pathway. PLoS ONE 6, e16422. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. J., Conze D. B., Li T., Srinivasula S. M., Ashwell J. D. (2006). NEMO is a sensor of Lys 63-linked polyubiquitination and functions in NF-kappaB activation. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 398–406 10.1038/ncb1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Gao J., Chung K. K., Huang H., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M. (2000). Parkin functions as an E2-dependent ubiquitin- protein ligase and promotes the degradation of the synaptic vesicle-associated protein, CDCrel-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 13354–13359 10.1073/pnas.240347797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Shimoji M., Thomas B., Moore D. J., Yu S. W., Marupudi N. I., Torp R., Torgner I. A., Ottersen O. P., Dawson T. M., Dawson V. L. (2005). Mitochondrial localization of the Parkinson’s disease related protein DJ-1: implications for pathogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 2063–2073 10.1093/hmg/ddi211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]