Abstract

Rationale: Lymphocytes have been shown to facilitate systemic inflammation and physiologic dysfunction in experimental models of severe sepsis. Our previous studies show that natural killer (NK) cells migrate into the peritoneal cavity during intraabdominal sepsis, but the trafficking of NKT and T lymphocytes has not been determined. The factors that regulate lymphocyte trafficking during sepsis are currently unknown.

Objectives: To ascertain the importance of CXC chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3) as a regulator of lymphocyte trafficking during sepsis and determine the contribution of CXCR3-mediated lymphocyte trafficking to the pathogenesis of septic shock.

Methods: Lymphocyte trafficking was evaluated in control and CXCR3-deficient mice using flow cytometry during sepsis caused by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Survival, core temperature, cytokine production, and bacterial clearance were measured as pathobiological endpoints.

Measurements and Main Results: This study shows that concentrations of the CXCR3 ligands CXCL9 (monokine induced by interferon γ, MIG) and CXCL10 (interferon γ–induced protein 10, IP-10) increase in plasma and the peritoneal cavity after CLP, peak at 8 hours after infection, and are higher in the peritoneal cavity than in plasma. The numbers of CXCR3+ NK cells progressively decreased in spleen after CLP with a concomitant increase within the peritoneal cavity, a pattern that was ablated in CXCR3-deficient mice. CXCR3-dependent recruitment of T cells was also evident at 16 hours after CLP. Treatment of mice with anti-CXCR3 significantly attenuated CLP-induced hypothermia, decreased systemic cytokine production, and improved survival.

Conclusions: CXCR3 regulates NK- and T-cell trafficking during sepsis and blockade of CXCR3 attenuates the pathogenesis of septic shock.

Keywords: septic shock, natural killer cells, T cells, natural killer T cells

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

CXC chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3) is a known regulator of lymphocyte trafficking. However, the role of CXCR3 in the pathogenesis of septic shock has not been elucidated.

What This Study Adds to the Field

This study shows that CXCR3 is an essential factor controlling the trafficking of lymphocytes during sepsis and that blockade of CXCR3 decreases systemic inflammation and improves survival of mice with septic shock caused by cecal ligation and puncture.

Previous studies from our laboratory, and others, show that natural killer (NK), natural killer T (NKT), and CD8+ T lymphocytes participate in the propagation of acute inflammation and physiologic dysfunction during septic shock (1–5). Mice depleted of CD8+ T and NK cells display improved survival, less hypothermia, less metabolic acidosis, improved cardiovascular function, and decreased systemic cytokine production compared with control mice during intraabdominal sepsis caused by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) (1, 2). Selective NK-cell depletion has also been shown to decrease systemic inflammation and improve survival in experimental models of pneumococcal pneumonia, systemic Escherichia coli infection, and polytrauma (3–5). The contribution of NKT cells to the pathophysiology of septic shock has been demonstrated by Hu and colleagues, who reported decreased sepsis-induced systemic cytokine production and organ injury in NKT-deficient Jα281 knockout mice (6). Wesche-Soldato and coworkers have shown that CD8+ T cells facilitate acute liver injury during sepsis caused by CLP (7). Those experimental findings correlate with a clinical study by Zeerleder and colleagues that showed an association between cytotoxic T- and NK-cell activation and the development of multiorgan failure and death in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock (8). However, the mechanisms underlying lymphocyte-mediated systemic inflammation and organ injury during severe sepsis are poorly understood.

Our previous studies show that NK cells rapidly migrate into the peritoneal cavity during CLP-induced peritonitis (9). However, little is known about the trafficking of NKT and T cells during sepsis. Furthermore, the contribution of lymphocyte trafficking to the pathogenesis of sepsis has not been determined. Previous studies have shown that CXC chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3) regulates lymphocyte trafficking during viral infections, cancer, transplantation, and chronic autoimmune diseases (10). However, the functional importance of CXCR3 as a regulator of lymphocyte trafficking during bacterial sepsis has not been determined, nor has the contribution of the CXCR3 axis to the pathogenesis of septic shock. CXCR3 is a G protein–coupled chemokine receptor that is expressed preferentially by NK, NKT, and T lymphocytes (10–14). CXCR3 is activated by three ligands, CXCL9 (monokine induced by interferon γ, MIG), CXCL10 (interferon γ–induced protein 10, IP-10), and CXCL11 (interferon-inducible T-cell α chemoattractant, i-TAC), which are produced primarily by activated macrophages and endothelial cells in response to type I interferons (IFNα/β) and IFNγ (12). The CXCR3 ligands act redundantly, cooperatively, and, in some cases, antagonistically to regulate lymphocyte trafficking depending on the disease process and tissue under study (11).

High levels of CXCL10 have been observed in the plasma of septic patients, and plasma CXCR3 concentrations have been shown to generally parallel the severity of sepsis (15, 16) Punyadeera and colleagues (16) showed that increasing plasma CXCL10 concentrations were predictive of progression from sepsis to septic shock in critically ill patients. In other clinical studies, plasma CXCL10 concentrations of greater than 1,250 pg/ml were predictive of neonatal sepsis and systemic infection with high sensitivity and specificity (17, 18). However, the functional role of CXCR3 in regulating lymphocyte trafficking and function during severe sepsis has not been determined, nor has the contribution of CXCR3 activation to the pathogenesis of septic shock. Furthermore, the ability of CXCR3 blockade to decrease the severity of sepsis has not been determined.

We hypothesized that CXCR3 functions as an important regulator of lymphocyte trafficking during intraabdominal sepsis caused by CLP and that blockade or depletion of CXCR3 will attenuate CLP-induced pathobiology. To test those hypotheses, lymphocyte trafficking, bacterial clearance, cytokine production, physiologic function, and survival were measured in control and CXCR3-deficient mice during sepsis caused by CLP.

Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of abstracts (19–21).

Methods

Mice

Female 8- to 10-week-old C57BL/6J wild-type and homozygous CXCR3 null mice (B6.129P2-Cxcr3tm1Dgen/J, CXCR3KO) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). In some experiments, wild-type mice received intraperitoneal injection with anti-CXCR3 IgG (clone CXCR3-173, 100 μg, eBioscience, San Diego, CA) or isotype-matched, nonspecific IgG (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) 24 hours and 1 hour before CLP. All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Medical Branch and complied with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals.

Cecal Ligation and Puncture

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane in oxygen. After shaving and aseptic preparation, a 1- to 2-cm midline incision was made through the abdominal wall; the cecum was identified and ligated with a 3-0 silk tie at 1 cm from the tip. A double puncture of the cecal wall was performed with a 20-gauge needle. The incision was closed with Autoclips (Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, MD). Mice were resuscitated by intraperitoneal injection with either 1 ml of lactated Ringer's solution or lactated Ringer's solution containing Primaxin (imipenem/cilastatin, 25 mg/kg, Merck and Co., Whitehouse Station, NJ) immediately after CLP. Mice received buprenorphine (2.5 μg subcutaneously) at the time of surgery and every 8–12 hours thereafter for analgesia.

ELISA

Heparinized blood was obtained by carotid laceration and plasma was harvested from centrifuged blood (2,000 × g for 15 min). The peritoneal cavity was lavaged with 3 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Urea was used as an endogenous marker of dilution for peritoneal lavage samples because urea readily diffuses freely throughout the tissue and fluid compartments (22). When the urea concentrations in plasma and a peritoneal lavage sample are known, the dilution of the initial volume of peritoneal fluid obtained can be calculated as previously described (23, 24). The urea contents of peritoneal fluid and plasma were determined using iStat Chem8 cartridges (Abbott Point of Care, Princeton, NJ).

Interleukin-6 (IL-6), macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2), CXCL9, and CXCL10 concentrations in peritoneal lavage fluid and plasma were measured using an ELISA according to the manufacturer's protocol (eBioscience; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Cytokine levels were determined by measuring optical density at 450 nm using a microtiter plate reader (Dynatech Laboratories, Chantilly, VA).

Measurement of Temperature and Bacterial Counts

Body temperature was measured by insertion of a rectal temperature probe after induction of anesthesia with 2–3% isoflurane in oxygen. Bacterial counts were performed on blood, peritoneal lavage fluid, and lung. Samples of plasma and peritoneal lavage fluid were obtained as described above. Lung tissue was harvested under aseptic conditions, weighed, and homogenized in sterile PBS to achieve a final concentration of 11 mg of tissue per ml of saline. Samples were serially diluted in sterile saline and cultured on tryptic soy agar pour plates. Plates were incubated (37°C) for 24–48 hours, and colony counts were performed by direct visualization.

Flow Cytometry

Splenocytes and hepatic leukocytes were isolated as previously described (25). Briefly, spleens were harvested and placed in 35-mm dishes containing RPMI-1640 media with 10% fetal bovine serum, and homogenized by smashing with the plunger from a 1-ml syringe. The dispersed spleens were passed through a 70-μm nylon mesh, and erythrocytes were lysed (Erythrocyte Lysis Kit; R&D Systems). Livers were harvested and pressed through a 70-μm steel mesh, and the liver suspension was mixed with isotonic 35% Percoll and centrifuged (750 × g for 15 min). The supernatant was discarded, erythrocytes were lysed, and the resulting mononuclear cells were obtained. Viability of cells was greater than 95% in all cases as determined by trypan blue exclusion.

Cells (1 × 106/tube) were placed in polystyrene tubes and incubated with anti-mouse CD16/32 (eBioscience) to block nonspecific Fc receptor–mediated antibody binding. After washing, fluorochrome-conjugated labeling antibodies or isotype controls (0.5–1 g /tube) were added, incubated (4°C) for 30 min, and washed with 2 ml of cold PBS. Cells were fixed with 500 μl of 1% paraformaldehyde. Antibodies used in the analyses included fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-CD3, phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-NK1.1 and allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-CXCR3 (eBioscience and R&D Systems). Samples were analyzed with a FACSCanto flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Statistics

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Data from multiple group experiments were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Tukey's test to compare groups. Paired data were analyzed using a paired t test. For measurements of bacterial cfu, groups were compared using a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by a post hoc Dunn's test. Survival data were analyzed using the log-rank test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all experiments. All values are presented as the mean ± SEM, except for bacterial counts, for which median values are designated.

Results

Concentrations of the CXCR3 Ligands CXCL9 and CXCL10 Increase after CLP

Concentrations of the CXCR3 ligands CXCL9 and CXCL10 increased in peritoneal lavage fluid and plasma within 4 hours after CLP and remained elevated at 8 and 16 hours with the highest concentrations being measured at 8 hours (Figure 1). Concentrations of both ligands were significantly higher in the peritoneal cavity than in plasma at all time points. CXCL11 was not measured because it is not expressed by C57BL/6J mice due to a frameshift mutation (26).

Figure 1.

Concentrations of CXCL9 and CXCL10 in peritoneal lavage fluid and plasma after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Samples were harvested at the indicated time points after CLP. Chemokine concentrations were measured by ELISA. *P < 0.05 compared with 0 hour control (no CLP), +P < 0.05 compared with plasma, n = 10 mice per group; values are expressed as mean ± SEM. P = plasma; PF = peritoneal lavage fluid.

Lymphocyte Trafficking during CLP-induced Sepsis Is Regulated by Activation of CXCR3

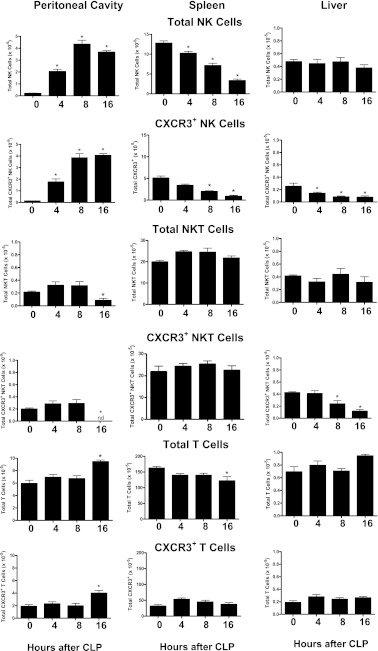

Focus was placed on the trafficking of NK, NKT, and T cells because CXCR3 expression predominates among those cell populations. NK-cell numbers decreased in spleen and increased in the peritoneal cavity in a time-dependent course after CLP (Figure 2). The vast majority of NK cells that entered the peritoneal cavity were CXCR3+ (Figure 2). The numbers of CXCR3+ splenic NK cells progressively decreased after CLP. Although the total numbers of NK cells in the liver did not change after CLP, the number of CXCR3+ hepatic NK cells progressively decreased over the 16-hour observation period (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The numbers of total and CXCR3+ natural killer (NK) (NK1.1+CD3−), natural killer T (NKT) (NK1.1+CD3+), and T (NK1.1−CD3+) cells in peritoneal cavity, spleen, and liver were analyzed at the indicated time points after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) using flow cytometry. *P < 0.05 compared with 0 hour control (no CLP), n = 5 mice per group; values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

The total numbers of NKT cells in spleen and liver did not change after CLP, but their total numbers in the peritoneal cavity were significantly decreased at 16 hours (Figure 2). The numbers of intraperitoneal CXCR3+ NKT cells were decreased at 16 hours after CLP, and the number of CXCR3+ NKT cells in the liver progressively decreased over the observation period.

The total numbers of T cells in the peritoneal cavity were increased and their numbers in the spleen were decreased at 16 hours after CLP with no significant change in the numbers of T cells in liver (Figure 2). The numbers of CXCR3+ T cells were increased in the peritoneal cavity at 16 hours after CLP with no significant change in spleen or liver (Figure 2). Determination of the percentage of CXCR3+ cells (CXCR3+ cells/Total cells × 100) among the lymphocyte populations showed that 20–40% of NK, greater than 80% of NKT, and 25–35% of T cells were CXCR3+, with some variability among tissues (Figure 2).

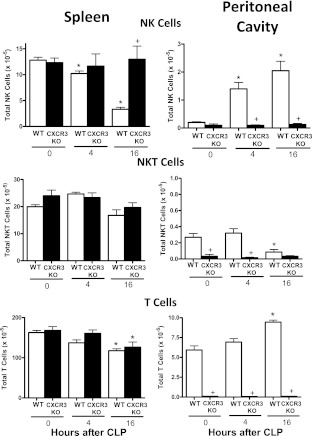

Lymphocyte trafficking was also evaluated in CXCR3-deficient mice (CXCR3KO) after CLP (Figure 3). The observed decrease in splenic NK cells and increase in intraperitoneal NK-cell numbers that was observed in wild-type mice after CLP was not seen in CXCR3KO mice (Figure 3). The numbers of splenic NKT cells did not change significantly in wild-type or CXCR3 knockout mice after CLP. T-cell numbers were significantly decreased in the spleens of wild-type and CXCR3KO mice at 16 hours after CLP (Figure 3). NKT-cell numbers in the peritoneal cavity were significantly decreased and T-cell numbers were increased at 16 hours after CLP (Figure 3). Interestingly, the peritoneal cavity of CXCR3KO mice was nearly devoid of NK, NKT, and T cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Lymphocyte trafficking in wild-type (WT) and CXCR3 knockout (KO) mice after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Total numbers of natural killer (NK), natural killer T (NKT), and T cells in spleen and peritoneal cavity were determined by flow cytometry at the designated time points after CLP. *P < 0.05 compared with 0 hour control (no CLP), +P < 0.05 compared with WT, n = 5 mice per group; values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

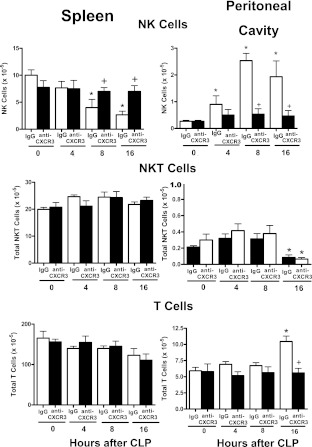

Evaluation of lymphocyte trafficking in wild-type mice treated with nonspecific IgG or anti-CXCR3 IgG showed that treatment with anti-CXCR3 attenuated NK- and T-cell migration during CLP-induced sepsis (Figure 4). NK-cell numbers decreased in the spleen and increased in the peritoneal cavity in mice treated with nonspecific IgG but not in mice treated with anti-CXCR3 (Figure 4). The numbers of NKT cells in the spleen did not change after CLP in mice treated with IgG or anti-CXCR3 (Figure 4). Splenic T-cell numbers were significantly decreased in IgG- and anti-CXCR3–treated mice at 16 hours after CLP. NKT-cell numbers were decreased in the peritoneal cavity of mice treated with IgG or anti-CXCR3 at 16 hours after CLP (Figure 4). T-cell numbers were increased in the peritoneal cavity of IgG-treated mice at 16 hours after CLP but not in mice treated with anti-CXCR3 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Lymphocyte trafficking in wild-type mice treated with nonspecific IgG (IgG) or anti-CXCR3 IgG after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Total numbers of natural killer (NK), natural killer T (NKT), and T cells in spleen and peritoneal cavity were determined by flow cytometry at the designated time points after CLP. *P < 0.05 compared with 0 hour control (no CLP), +P < 0.05 compared with IgG-treated wild-type mice (IgG), n = 5 mice per group; values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Effect of CXCR3 Deficiency on the Pathogenesis of CLP-induced Septic Shock

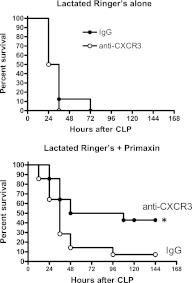

In the absence of antibiotics, treatment with anti-CXCR3 did not improve survival compared with mice treated with nonspecific IgG (Figure 5). However, survival was significantly improved in mice treated with anti-CXCR3 plus Primaxin compared with mice receiving nonspecific IgG plus Primaxin (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Survival of wild-type mice treated with nonspecific IgG or anti-CXCR3 after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Mice were treated with IgG or anti-CXCR3 at 24 hours and 1 hour prior to CLP. Mice were resuscitated with lactated Ringer's solution alone or lactated Ringer's plus Primaxin immediately after CLP. *P < 0.05 compared with IgG, n = 14 mice per group. Statistical comparison was made using the log-rank test.

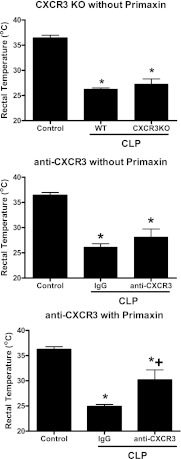

CLP-induced sepsis causes significant hypothermia as indicated by decreased core body temperature compared with control, nonseptic mice (Figure 6). In the absence of antibiotic treatment, rectal temperature was equally decreased when comparing wild-type mice to CXCR3KO mice or in wild-type mice treated with nonspecific IgG compared with those treated with anti-CXCR3 (Figure 6). However, in mice receiving Primaxin, rectal temperature was significantly higher in mice treated with anti-CXCR3 compared with mice treated with IgG (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of CXCR3 deficiency or blockade on rectal temperature in septic mice. Rectal temperature in control (nonseptic) mice was compared with rectal temperature in wild-type (WT) and CXCR3 knockout (CXCR3KO) mice or with that in WT mice treated with nonspecific IgG or anti-CXCR3. Mice were resuscitated with lactated Ringer's solution alone (without Primaxin) or with lactated Ringer's solution plus Primaxin (with Primaxin). Rectal temperature was measured in mice at 24 hours after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). *P < 0.05 compared with control (no CLP), +P < 0.05 compared with IgG-treated mice, n = 10 mice per group; values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

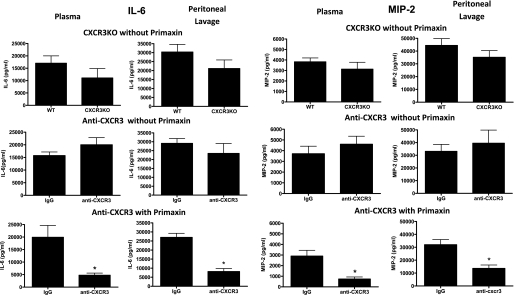

Similarly, no significant difference in IL-6 and MIP-2 concentrations were observed in plasma or peritoneal lavage fluid when comparing wild-type mice with CXCR3KO mice or wild-type mice treated with nonspecific IgG with those treated with anti-CXCR3 in the absence of Primaxin treatment (Figure 7). However, in mice treated with Primaxin, IL-6 and MIP-2 concentrations in plasma and peritoneal lavage fluid were lower in mice treated with anti-CXCR3 compared with those treated with nonspecific IgG (Figure 7). IL-6 and MIP-2 were measured as indices of systemic inflammation because previous studies from our lab and others have shown that systemic concentrations of those cytokines correlate with outcome in the CLP model (27–29).

Figure 7.

Plasma and peritoneal lavage interleukin-6 (IL-6) and macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2) concentrations in control and CXCR3-deficient mice after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Samples were harvested at 24 hours after CLP and cytokine concentrations were measured by ELISA. *P < 0.05 compared with IgG, n = 10 mice per group; values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

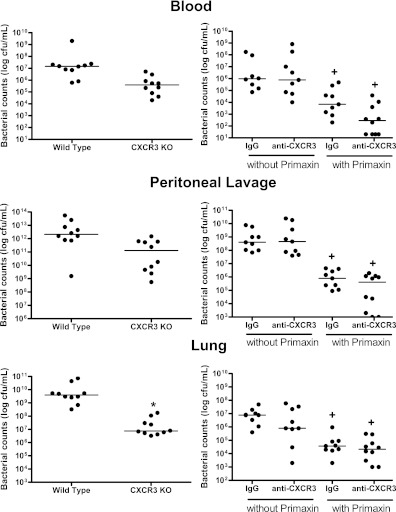

Bacterial counts were not significantly different in CXCR3KO mice compared with wild-type mice at any of the sites examined with the exception of the lung in which median bacterial counts were significantly lower than in wild-type mice (Figure 8). CXCR3KO mice did not receive treatment with Primaxin. In the absence of treatment with Primaxin, bacterial counts were not significantly different at all sites when comparing wild-type mice treated with nonspecific IgG with those treated with anti-CXCR3 IgG (Figure 8). Bacterial counts in all tissues were significantly (P < 0.05) lower in mice treated with Primaxin compared with those that did not receive antibiotics (Figure 8). Bacterial counts were not significantly different in mice treated with anti-CXCR3 IgG and Primaxin compared with mice treated with nonspecific IgG and Primaxin (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Bacterial colony-forming units in blood, peritoneal lavage fluid, and lung after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Bacterial counts were measured at 24 hours after CLP. n = 9–10 mice per group; the median value is designated. *P < 0.05 compared with wild type, +P < 0.05 compared with mice that did not receive Primaxin, n = 10 mice per group.

Discussion

Previous studies have documented high concentrations of CXCR3 ligands in plasma during severe sepsis and septic shock in adults and neonates (15–18). However, the functional important of CXCR3 in regulating lymphocyte trafficking during severe sepsis has not been determined, nor has the contribution of CXCR3 activation to the pathogenesis of septic shock. The present study supports the hypothesis that NK and T-cell trafficking during CLP-induced septic shock is regulated at least in part through activation of CXCR3. The entry of CXCR3+ NK cells into the peritoneal cavity after CLP paralleled a decline in splenic NK-cell numbers, and both alterations were ablated in CXCR3-deficient mice, as might be predicted. CXCR3-dependent recruitment of T cells into the peritoneal cavity was also evident at 16 hours after CLP. The observed NK- and T-cell trafficking coincided with CLP-induced elevations in CXCL9 and CXCL10 in plasma and peritoneal lavage fluid. These observations provide new information regarding the trafficking of lymphocytes during sepsis. The importance of CXCR3 as a regulator of NK- and T-cell migration during sepsis has not been previously demonstrated. In addition, we report the novel observation that CXCR3 activation plays a functional role in the pathogenesis of CLP-induced septic shock. Blockade of CXCR3, in combination with antibiotic treatment, significantly improved survival, decreased systemic cytokine production and attenuated the development of hypothermia during septic shock.

Previous studies from our laboratory, and others, have demonstrated that NK cells contribute to systemic inflammation and physiologic dysfunction during sepsis and polytrauma (1–5). However, the mechanisms underlying NK cell–mediated pathobiology have not been defined. NK cells do not uniformly express CXCR3. The proportion of CXCR3+ cells varied between 20 and 40% in the peritoneal cavity, spleen, and liver in this study (see Figure 2). That finding is consistent with the work of Marquardt and colleagues, who showed that 20–60% of NK cells are CXCR3+ and that the proportion of CXCR3+ NK cells differs among tissues (30). CXCR3+ NK cells in the mouse are functionally similar to human CD56bright NK cells in that they have significant migratory potential and the capacity to secrete IFN-γ and TNF-α at higher levels than CXCR3− NK cells (30). Hayakawa and Smyth also showed two major subsets of NK cells in the mouse. They reported that CD27hi NK cells coexpress CXCR3, encompass 20–50% of total NK cells, and show chemotactic responses to CXCR3 ligands (31). Both studies indicated that CXCR3− NK cells have low migratory potential during periods of inflammation, a mature phenotype characterized by high expression of CD11b, and high cytotoxic potential. CXCR3− NK cells also secrete lesser amounts of IFN-γ and TNF-α. Results from the present study support the argument that the CXCR3+ subpopulation of NK cells facilitates the pathogenesis of CLP-induced septic shock. That conclusion is based upon the observation that blockade of CXCR3 improved survival, decreased systemic cytokine production, and attenuated physiologic dysfunction in mice treated with antibiotics. It is also possible that CXCR3− NK cells contribute to the pathogenesis of sepsis. However, that possibility was not directly examined in the present study. Nevertheless, our previous studies show that NK cell–deficient mice treated with Primaxin show survival rates of 30–40% during CLP-induced septic shock, which is very similar to the survival rates observed in mice treated with Primaxin and anti-CXCR3 in the present study.

Approximately 40% of hepatic NK cells were observed to be CXCR3+ in our study, and the total numbers of hepatic NK cells did not change after CLP. However, CXCR3 expression by hepatic NK cells decreased within 4 hours and continued to decline throughout the observation period. Activation of NK cells is known to cause internalization and down-regulation of CXCR3 (32, 33). Therefore, it is likely that hepatic CXCR3+ NK cells become activated during CLP-induced sepsis but do not migrate out of the liver. Likewise, the numbers of hepatic NKT cells, of which greater than 90% were observed to be CXCR3+, also did not change after CLP but showed progressive down-regulation of CXCR3. Previous studies have shown that 80–100% of mouse and human NKT cells, in various tissue compartments, are CXCR3+ (34, 35). Furthermore, the studies published to date indicate that activation of CXCR3 may function to regulate the migration of NKT cells within their tissue of origin during periods of bacterial infection. Lee and colleagues showed that CXCR3 activation is important for intrahepatic NKT-cell migration during Borrelia burgdorferi infection (36). Taken together, our findings indicate that hepatic NK and NKT cells become activated during CLP-induced sepsis but do not migrate out of the liver.

CXCR3-dependent trafficking of T cells into the peritoneal cavity was observed at 16 hours after CLP in the present study. However, T cells entered the peritoneal cavity much later than NK cells after CLP, and the proportional increase in intraperitoneal T cells was much smaller than for NK cells. Therefore, the functional importance of T-cell migration into the peritoneal cavity is not completely evident. Our study indicates that blockade of CXCR3-mediated T-cell migration is associated with improved outcome in a model of CLP-induced septic shock, which suggests that T-cell trafficking is deleterious under those conditions. However, the trafficking of T cells to sites of infection may facilitate antimicrobial functions during acute bacterial infections under some conditions. Kasten and coworkers have postulated that CXCR3-dependent migration of γδ T cells to sites of bacterial infection aids the recruitment of neutrophils and facilitates clearance of bacteria through production of IL-17 in mice treated with IL-7 (37). However, functional studies to assess CXCR3-dependent lymphocyte trafficking were not performed in that study. Therefore, the functional importance of CXCR3 in facilitating γδ T-cell recruitment during CLP-induced sepsis remains to be fully determined. We did not observe changes in bacterial clearance in CXCR3-deficient mice in our study. However, one major difference between our study and that of Kasten and colleagues is that our mice were not treated with IL-7 (37). Another issue that remains to be resolved is the origin of the T cells that enter the peritoneal cavity after CLP. Although splenic T cells decreased in parallel with the increase in intraperitoneal T cells, that alteration was seen in both control and CXCR3-deficient mice. That would suggest that the decline in splenic T cells after CLP is independent of CXCR3 and may be due to apoptosis as previously reported by several investigators (38, 39).

The present study demonstrates that treatment with anti-CXCR3 IgG in combination with antibiotics decreases systemic inflammation and improves survival in septic mice, but no benefit was observed in the absence of antibiotic treatment. In addition, bacterial clearance was not affected by CXCR3 blockade, regardless of whether antibiotics were given. These findings are consistent with the conclusion that the deleterious effects of CXCR3 activation are independent of bacterial clearance mechanisms. Interestingly, Cuenca and coworkers have reported that CXCR3 is important for neutrophil and macrophage recruitment during neonatal sepsis (40). Neonatal CXCR3KO mice showed decreased numbers of neutrophils and macrophages at the site of infection and increased mortality compared with wild-type controls. The effect of CXCR3 deficiency on lymphocyte recruitment in CXCR3-deficient neonates was not reported, nor was bacterial burden. However, they reported that CXCR3 expression was induced among neutrophils and macrophages and postulated that CXCR3 directly regulates myeloid cell recruitment during bacterial sepsis in neonatal mice. The difference in results between our study and that of Cuenca and colleagues is likely due to differences in the immune response to systemic bacterial infection among mature and neonatal mice (40).

In conclusion, the present study shows that CXCR3, at least in part, regulates the trafficking of NK and T cells into the peritoneal cavity during CLP-induced septic shock. Furthermore, CLP induces activation of hepatic CXCR3+ NK and NKT cells but does not induce mobilization of those cell populations from the liver. CXCR3 blockade, in combination with antibiotic treatment, results in improved survival, decreased systemic cytokine production, and attenuated physiologic dysfunction. Therefore, CXCR3 activation appears to play a functional role in regulating lymphocyte trafficking and facilitating the pathogenesis of CLP-induced septic shock.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by grants R01 GM66885 from the National Institutes of Health and 8780 from the Shriners of North America.

Author Contributions: D.S.H. is a post-doctoral fellow. She made major contributions to the design and interpretation of experiments and was actively involved in all experimental components of the study. B.R.D. is a medical student. He was actively involved in all experiments performed, including surgical procedures, microbiology, flow cytometry, and cytokine measurements. He was actively involved in experimental design and interpretation. G.F. was actively involved in performing ELISAs, microbiological analyses, and surgical procedures. She was instrumental in interpreting findings and troubleshooting technical aspects of the study. T.E.T.-K. was actively involved in the design and interpretation of experiments. She was actively involved in supervising and assisting with flow cytometry experiments. E.N.S. is a medical student. He worked closely with D.S.H. in the design, execution, and interpretation of experiments performed. E.R.S. is the Principal Investigator and is responsible for all conceptual and technical aspects of this study.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1560OC on December 1, 2011

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Sherwood ER, Enoh VT, Murphey ED, Lin CY. Mice depleted of CD8+ T and NK cells are resistant to injury caused by cecal ligation and puncture. Lab Invest 2004;84:1655–1665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tao W, Sherwood ER. Beta2-microglobulin knockout mice treated with anti-asialoGM1 exhibit improved hemodynamics and cardiac contractile function during acute intra-abdominal sepsis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2004;286:R569–R575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerr AR, Kirkham LA, Kadioglu A, Andrew PW, Garside P, Thompson H, Mitchell TJ. Identification of a detrimental role for NK cells in pneumococcal pneumonia and sepsis in immunocompromised hosts. Microbes Infect 2005;7:845–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barkhausen T, Frerker C, Putz C, Pape HC, Krettek C, van Griensven M. Depletion of NK cells in a murine polytrauma model is associated with improved outcome and a modulation of the inflammatory response. Shock 2008;30:401–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badgwell B, Parihar R, Magro C, Dierksheide J, Russo T, Carson WE., III Natural killer cells contribute to the lethality of a murine model of Escherichia coli infection. Surgery 2002;132:205–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu CK, Venet F, Heffernan DS, Wang YL, Horner B, Huang X, Chung CS, Gregory SH, Ayala A. The role of hepatic invariant NKT cells in systemic/local inflammation and mortality during polymicrobial septic shock. J Immunol 2009;182:2467–2475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wesche-Soldato DE, Chung CS, Gregory SH, Salazar-Mather TP, Ayala CA, Ayala A. CD8+ T cells promote inflammation and apoptosis in the liver after sepsis: role of fas-fasl. Am J Pathol 2007;171:87–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeerleder S, Hack CE, Caliezi C, van Mierlo G, Eerenberg-Belmer A, Wolbink A, Wuillenmin WA. Activated cytotoxic T cells and NK cells in severe sepsis and septic shock and their role in multiple organ dysfunction. Clin Immunol 2005;116:158–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Etogo AO, Nunez J, Lin CY, Toliver-Kinsky TE, Sherwood ER. NK but not CD1-restricted NKT cells facilitate systemic inflammation during polymicrobial intra-abdominal sepsis. J Immunol 2008;180:6334–6345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groom JR, Luster AD. CXCR3 ligands: redundant, collaborative and antagonistic functions. Immunol Cell Biol 2011;89:207–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cole KE, Strick CA, Paradis TJ, Ogborne KT, Loetscher M, Gladue RP, Lin W, Boyd JG, Moser B, Wood DE, et al. Interferon-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant (i-Tac): a novel non-elr cxc chemokine with potent activity on activated T cells through selective high affinity binding to cxcr3. J Exp Med 1998;187:2009–2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohmori Y, Hamilton TA. Cooperative interaction between interferon (IFN) stimulus response element and kappa B sequence motifs controls IFN gamma- and lipopolysaccharide-stimulated transcription from the murine ip-10 promoter. J Biol Chem 1993;268:6677–6688 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beima KM, Miazgowicz MM, Lewis MD, Yan PS, Huang TH, Weinmann AS. T-bet binding to newly identified target gene promoters is cell type-independent but results in variable context-dependent functional effects. J Biol Chem 2006;281:11992–12000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maghazachi AA. Role of chemokines in the biology of natural killer cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2010;341:37–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thair SA, Walley KR, Nakada TA, McConechy MK, Boyd JH, Wellman H, Russell JA. A single nucleotide polymorphism in NF-kappaB inducing kinase is associated with mortality in septic shock. J Immunol 2011;186:2321–2328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Punyadeera C, Schneider EM, Schaffer D, Hsu HY, Joos TO, Kriebel F, Weiss M, Verhaegh WF. A biomarker panel to discriminate between systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis and sepsis severity. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2010;3:26–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen HL, Hung CH, Tseng HI, Yang RC. Plasma IP-10 as a predictor of serious bacterial infection in infants less than 4 months of age. J Trop Pediatr 2011;57:145–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng PC, Li K, Chui KM, Leung TF, Wong RP, Chu WC, Wong E, Fok TF. IP-10 is an early diagnostic marker for identification of late-onset bacterial infection in preterm infants. Pediatr Res 2007;61:93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herzig DS, Driver BR, Fang G, Sherwood ER. Role of CXCR3 in septic shock [abstract]. Shock 2011;1:A75 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherwood ER, Herzig DS, Romero C, Driver BR, Fang G. The role of CXCR3 in the pathogenesis of acute intraabdominal sepsis [abstract]. SLB/IEIIS 2010;A248 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herzig DS, Fang G, Sherwood ER. Regulation of NK cell function during acute bacterial peritonitis by CXCR3 [abstract]. Keystone 2011;A4–A11 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelton JG, Ulan R, Stiller C, Holmes E. Comparison of chemical composition of peritoneal fluid and serum: a method for monitoring dialysis patients and a tool for assessing binding to serum proteins in vivo. Ann Intern Med 1978;89:67–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dupont H, Montravers P, Mohler J, Carbon C. Disparate findings on the role of virulence factors of Enterococcus faecalis in mouse and rat models of peritonitis. Infect Immun 1998;66:2570–2575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montravers P, Mohler J, Saint Julien L, Carbon C. Evidence of the proinflammatory role of Enterococcus faecalis in polymicrobial peritonitis in rats. Infect Immun 1997;65:144–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherwood ER, Lin CY, Tao W, Hartmann CA, Dujon JE, French AJ, Varma TK. Beta 2 microglobulin knockout mice are resistant to lethal intraabdominal sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:1641–1649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang B, Chan YK, Lu B, Diamond MS, Klein RS. CXCR3 mediates region-specific antiviral T cell trafficking within the central nervous system during West Nile virus encephalitis. J Immunol 2008;180:2641–2649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enoh VT, Lin SH, Lin CY, Toliver-Kinsky T, Murphey ED, Varma TK, Sherwood ER. Mice depleted of alphabeta but not gammadelta T cells are resistant to mortality caused by cecal ligation and puncture. Shock 2007;27:507–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiao H, Siddiqui J, Remick DG. Mechanisms of mortality in early and late sepsis. Infect Immun 2006;74:5227–5235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Remick DG, Bolgos G, Copeland S, Siddiqui J. Role of interleukin-6 in mortality from and physiologic response to sepsis. Infect Immun 2005;73:2751–2757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marquardt N, Wilk E, Pokoyski C, Schmidt RE, Jacobs R. Murine cxcr3+cd27bright NK cells resemble the human CD56bright NK-cell population. Eur J Immunol 2010;40:1428–1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayakawa Y, Smyth MJ. CD27 dissects mature NK cells into two subsets with distinct responsiveness and migratory capacity. J Immunol 2006;176:1517–1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gregoire C, Cognet C, Chasson L, Coupet CA, Dalod M, Reboldi A, Marvel J, Sallusto F, Vivier E, Walzer T. Intrasplenic trafficking of natural killer cells is redirected by chemokines upon inflammation. Eur J Immunol 2008;38:2076–2084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dagan-Berger M, Feniger-Barish R, Avniel S, Wald H, Galun E, Grabovsky V, Alon R, Nagler A, Ben-Baruch A, Peled A. Role of CXCR3 carboxyl terminus and third intracellular loop in receptor-mediated migration, adhesion and internalization in response to CXCL11. Blood 2006;107:3821–3831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas SY, Hou R, Boyson JE, Means TK, Hess C, Olson DP, Strominger JL, Brenner MB, Gumperz JE, Wilson SB, et al. CD1d-restricted NKT cells express a chemokine receptor profile indicative of Th1-type inflammatory homing cells. J Immunol 2003;171:2571–2580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uppaluri R, Sheehan KC, Wang L, Bui JD, Brotman JJ, Lu B, Gerard C, Hancock WW, Schreiber RD. Prolongation of cardiac and islet allograft survival by a blocking hamster anti-mouse CXCR3 monoclonal antibody. Transplantation 2008;86:137–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee WY, Moriarty TJ, Wong CH, Zhou H, Strieter RM, van Rooijen N, Chaconas G, Kubes P. An intravascular immune response to Borrelia burgdorferi involves Kupffer cells and iNKT cells. Nat Immunol 2010;11:295–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kasten KR, Prakash PS, Unsinger J, Goetzman HS, England LG, Cave CM, Seitz AP, Mazuski CN, Zhou TT, Morre M, et al. Interleukin-7 (IL-7) treatment accelerates neutrophil recruitment through gamma delta T-cell IL-17 production in a murine model of sepsis. Infect Immun 2010;78:4714–4722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peck-Palmer OM, Unsinger J, Chang KC, Davis CG, McDunn JE, Hotchkiss RS. Deletion of MyD88 markedly attenuates sepsis-induced T and B lymphocyte apoptosis but worsens survival. J Leukoc Biol 2008;83:1009–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ayala A, Chung CS, Song GY, Chaudry IH. IL-10 mediation of activation-induced Th1 cell apoptosis and lymphoid dysfunction in polymicrobial sepsis. Cytokine 2001;14:37–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cuenca AG, Wynn JL, Kelly-Scumpia KM, Scumpia PO, Vila L, Delano MJ, Mathews CE, Wallet SM, Reeves WH, Behrns KE, et al. Critical role for CXC ligand 10/CXC receptor 3 signaling in the murine neonatal response to sepsis. Infect Immun 2011;79:2746–2754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.