Abstract

MUC1 (or Muc1 in nonhuman species) is a membrane-tethered mucin expressed on the apical surface of mucosal epithelia (including those of the airways) that suppresses Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling. We sought to determine whether the anti-inflammatory effect of MUC1 is operative during infection with nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi), and if so, which TLR pathway was affected. Our results showed that: (1) a lysate of NTHi increased the early release of IL-8 and later production of MUC1 protein by A549 cells in dose-dependent and time-dependent manners, compared with vehicle control; (2) both effects were attenuated after transfection of the cells with a TLR2-targeting small interfering (si) RNA, compared with a control siRNA; (3) the NTHi-induced release of IL-8 was suppressed by an overexpression of MUC1, and was enhanced by the knockdown of MUC1; (4) the TNF-α released after treatment with NTHi was sufficient to up-regulate MUC1, which was completely inhibited by pretreatment with a soluble TNF-α receptor; and (5) primary murine tracheal surface epithelial (MTSE) cells from Muc1 knockout mice exhibited an increased in vitro production of NTHi-stimulated keratinocyte chemoattractant compared with MTSE cells from Muc1-expressing animals. These results suggest a hypothetical feedback loop model whereby NTHi activates TLRs (mainly TLR2) in airway epithelial cells, leading to the increased production of TNF-α and IL-8, which subsequently up-regulate the expression of MUC1, resulting in suppressed TLR signaling and decreased production of IL-8. This report is the first, to the best of our knowledge, demonstrating that the inflammatory response in airway epithelial cells during infection with NTHi is controlled by MUC1 mucin, mainly through the suppression of TLR2 signaling.

Keywords: bacteria, innate immunity, inflammation, TNF-α

Clinical Relevance

Although inflammation is an essential defense mechanism against invading pathogens, uncontrolled inflammation can cause serious damage to the host, leading to chronic inflammatory disease. We report that airway epithelial cells control inflammation during infection with Haemophilus influenzae by up-regulating the expression of MUC1 mucin in a timely manner, and we suggest a possible role for MUC1 in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cystic fibrosis.

Haemophilus influenzae is a Gram-negative bacterium that commensally colonizes the human respiratory tract. Some strains of H. influenzae possess a polysaccharide capsule and are subclassified into six capsular serotypes. Other strains have no capsule and are termed nontypeable H. influenzae (NTHi). Since the use of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine became widespread, bacterial infections attributable to the conversion of NTHi from a commensal to a pathogenic microorganism have become more prevalent. These infections include otitis media, conjunctivitis, and sinusitis in children, as well as pneumonia and the exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in adults (1–3).

NTHi induces innate and adaptive immune responses that are mounted by the host in an effort to clear the bacteria (4). In the context of innate immunity, NTHi expresses multiple Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands, and recent studies provide evidence for a critical role of TLRs in the immune response to NTHi. For example, Leichtle and colleagues (5) reported that the TLR4-mediated induction of TLR2 signaling is critical in the pathogenesis and resolution of NTHi otitis media. Similarly, Lim and colleagues (6) demonstrated that Streptococcus pneumoniae synergizes with NTHi to up-regulate TLR4-dependent TLR2 signaling. However, the mechanisms through which NTHi stimulates TLR signaling, and how the airways regulate NTHi-induced, TLR-dependent inflammation, remain to be clarified.

MUC1 (MUC1 in human and Muc1 in nonhuman species) is a membrane-tethered mucin expressed on the surface of epithelial cells, and in some hematopoietic cells (7). In a murine model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa airway infection, we previously showed that the inflammatory mediators produced in response to bacteria dramatically increased concentrations of Muc1 protein in the lung (8). Subsequently, we reported that the up-regulation of Muc1 expression attenuated airway inflammation in response to P. aeruginosa flagellin, the major structural protein of the bacterial flagellum and a TLR5 agonist (9, 10). The expression of MUC1/Muc1 was also shown to block airway inflammatory responses stimulated by other TLR ligands, including Pam3Cys, a synthetic analogue of bacterial lipoproteins that activates TLR2 [11]. These results suggest a general anti-inflammatory role for MUC1/Muc1 that is initiated late in the course of bacterial infection, and is responsible for returning the airways to their homeostatic state before infection (8, 12). However, no reports, to the best of our knowledge, have documented the effects of MUC1 on TLRs in response to an airway bacterial pathogen other than P. aeruginosa. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that inflammatory mediators released from lung epithelial cells by NTHi up-regulate the expression of MUC1 that, in turn, resolves inflammatory responses.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All chemicals and reagents used in this study were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO), unless otherwise indicated. A549 cells were cultured as previously described (12). Primary murine tracheal surface epithelial (MTSE) cells were prepared from 10-to 12-week-old, male C57BL6/J mice, and cultured using the same protocol previously described for primary rat tracheal surface epithelial cells (14). All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Temple University School of Medicine.

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

NTHi strain 12 was derived from a clinical isolate, and was kindly provided by Dr. Jian-Dong Li (University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY). A bacterial lysate was prepared by sonication (15). For the treatment of A549 cells, the NTHi lysate was diluted 1:3 or 1:5 (vol:vol) in Opti-MEM medium to final concentrations of approximately 25 μg/ml and 15 μg/ml, respectively. In some experiments, A549 cells were pretreated with a soluble form of the TNF receptor 1 (sTNFR1; Prospec, Rehovot, Israel) before treatment with NTHi.

Measurement of MUC1, IL-8, and TNF-α

A549 and MTSE cells were treated with NTHi lysate or PBS for varying time periods and subjected to MUC1 immunoblotting (11, 13). The amounts of IL-8, keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC), and TNF-α in the spent media were measured by ELISA, using commercially available antibodies (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and standards (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) (16).

Cell Transfection and NF-κB Reporter Luciferase Assay

A549 cells were transfected with plasmid encoding MUC1 (pcDNA-MUC1), empty vector (pcDNA3.1) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), MUC1-targeting small interfering (si) RNA, TLR2-targeting siRNA, nontargeting control siRNAs, plasmids encoding TLR2 (pTLR2), ELAM1 (pELAM1), and Renilla luciferase (phRL-TK) (11), using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All siRNAs were commercially prepared (Dharmacon, Waltham, MA). Sequences of MUC1 and control siRNAs were previously described (12). The nucleotide sequences of TLR2-targeting siRNA included 5′-GCCUUGACCUGUCCAACAAdTdT-3′ (sense) and 5′-UUGUUGGACAGGUCAAGGCdTdT-3′ (antisense), and those of nontargeting control siRNA included 5′-GCGCGCUUUGUAGGAUUCGdTdT-3′ (sense) and 5′-CGAAUCCUACAAAGCGCGCdTdT-3′ (antisense). The knockdown of MUC1 and TLR2 expression was confirmed by Western blot analysis and quantitative RT-PCR, respectively. For TLR2, total RNA was isolated using the Mini RNA Isolation II Kit (ZymoResearch, Orange, CA), and 1.0 μg of RNA was subjected to complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis and quantitative PCR, using cDNA synthesis and real-time PCR kits (Fermentas Life Sciences, Glen Burnie, MD). The TLR2 forward primer was 5′-GGCCAGCAAATTACCTGTGT-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-CCAGTGCTGTCCTGRGACAT-3′ (IDT, Coralville, IA). The glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) internal control forward primer was 5′-AGCCTCAAGATCATCAGCAATG-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-GTTGTCATGGATGACCTTGGC-3′. TLR2 and GAPDH cDNAs were amplified under conditions of initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles with denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds, annealing at 60°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 30 seconds. The levels of TLR2 transcripts were normalized to GAPDH transcripts, using the 2-ΔΔCt method. The NF-κB assay was conducted using the pELAM1-luc reporter construct, as previously described (11).

Statistical Analysis

All values were expressed as means ± SEM. Differences between means were compared using the Student t test or ANOVA, and were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

NTHi Lysate Increases the Release of IL-8 and Cellular Concentrations of MUC1 Protein in Human Lung Epithelial Cells

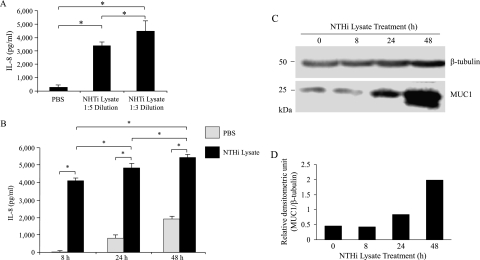

Multiple studies demonstrated the utility of NTHi lysate in elucidating the pathogenesis and host response to bacterial infection (6, 15, 17–23). Therefore, we initially determined whether NTHi lysate induces an in vitro inflammatory response in A549 cells, a human lung epithelial cell line that is commonly used to study airway inflammation. As the major inflammatory response, we chose the release of IL-8 rather than TNF-α, because the amount of IL-8 released was much greater compared with TNF-α. In addition, airway epithelial cells are the major source of IL-8 (24). The treatment of A549 cells with the NTHi lysate for 24 hours resulted in a dose-dependent increase in the release of IL-8, as assessed by increased concentrations of IL-8 protein in cell culture media, compared with cells treated with PBS alone (Figure 1A). Because the 1:3 dilution of lysate was more potent than the 1:5 dilution and showed no cytotoxicity, based on both cell morphology and the release of lactate dehydrogenase (data not shown), we used the 1:3 dilution, corresponding to approximately 25 μg protein/ml of NTHi lysate (henceforth termed “lysate”) for the remaining experiments. We next performed a time-course study of IL-8 release by the lysate. Concentrations of IL-8 in the spent culture media of the lysate treatment group were dramatically greater at 8 hours after treatment (undetectable for PBS, and 4,100 ± 100 pg/ml for lysate), and continued to increase up to at least 48 hours (Figure 1B). Interestingly, the amounts of IL-8 released between 8 and 24 hours, and between 24 and 48 hours, were relatively lower compared with those during the first 8 hours of treatment. This result could have been attributable to the effect of serum starvation (i.e., a decrease in cellular metabolism), the inhibition of feedback by cellular products in the spent media (including IL-8 itself), or the presence of an inhibitory mechanism that may have developed during the treatment period. On the other hand, although cellular concentrations of MUC1 protein did not change between 0 and 8 hours of lysate treatment, substantially increased concentrations of MUC1 were evident at 24 hours and 48 hours after treatment (Figures 1C and 1D). Thus, these results suggest that the treatment of A549 cells with the NTHi lysate increased both the release of IL-8 and cellular concentrations of MUC1 protein, but with different kinetics.

Figure 1.

Nontypeable H. influenzae (NTHi) lysate increases the release of IL-8 and expression of MUC1 protein. (A) A549 cells were serum-starved for 24 hours and treated for 8 hours with PBS or NTHi lysate (1:5 ≈ 15 μg/ml, 1:3 ≈ 25 μg/ml), and concentrations of IL-8 in culture media were quantified by ELISA. (B) A549 cells were serum-starved for 24 hours and treated for the indicated times with PBS or NTHi lysate (1:3 ≈ 25 μg/ml), and concentrations of IL-8 in culture media were quantified by ELISA. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05. (C) Cells in B were lysed at the end of treatment periods, and the lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-MUC1 antibody (CT2) or anti–β-tubulin antibody. (D) The density of each MUC1 band was normalized to the density of the corresponding β-tubulin band.

NTHi Lysate Increases Release of IL-8 and Expression of MUC1 through TLR2

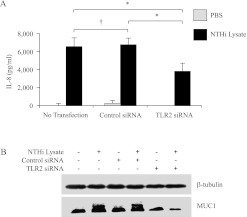

Previous studies demonstrated that TLR2 is involved in the cellular response to NTHi (5, 6). Therefore, we sought to determine whether TLR2 is involved in the NTHi-induced release of IL-8 and/or up-regulation of MUC1. The knockdown of TLR2 expression by RNA interference in A549 cells resulted in not only significantly decreased NTHi-induced concentrations of IL-8 (Figure 2A), but also a reduced up-regulation of MUC1 (Figure 2B), compared with cells treated with the negative control siRNA. Quantitative RT-PCR experiments established approximately 80% decreased concentrations of TLR2 mRNA in TLR2 siRNA-transfected cells compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (data not shown). These results indicate that the NTHi lysate induces the release of IL-8 and increases the expression of MUC1 in A549 cells, mainly through a TLR2-dependent mechanism.

Figure 2.

NTHi lysate increases the release of IL-8 and expression of MUC1 through Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2). A549 cells were nontransfected or transfected with nontargeting control or TLR2-targeting short interfering RNA (siRNA; 100 nM) for 72 hours before treatment with PBS or NTHi lysate (1:3) for 24 hours. (A) Spent culture media were collected at the end of treatment with lysate, and the amount of IL-8 was quantified by ELISA. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM (n = 5). *P < 0.05. †P > 0.05. (B) Cells were lysed at the end of treatment with NTHi lysate, and the lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-MUC1 antibody (CT2) or anti–β-tubulin antibody.

Overexpression of MUC1 Suppresses NTHi-Driven Release of IL-8

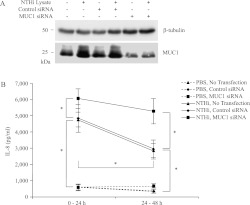

Our previous report demonstrated that the overexpression of MUC1 in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells or murine RAW264.7 macrophages suppressed the TLR-dependent activation of NF-κB and the production of proinflammatory cytokines (11). Therefore, we asked whether the overexpression of MUC1 in A549 cells suppressed the NTHi lysate-stimulated release of IL-8. The transient transfection of A549 cells with a pcDNA-MUC1 expression plasmid resulted in approximately 50-fold increased concentrations of MUC1 protein in whole-cell lysates, compared with nontransfected cells or cells transfected with the pcDNA3.1 empty vector (data not shown). The treatment of MUC1-overexpressing cells with NTHi lysate significantly decreased the release of IL-8, compared with nontransfected or pcDNA3.1-transfected cells (Figure 3). These results suggest that the relatively small increases in the lysate-induced release of IL-8 during the later time periods (i.e., 8–24 h and 24–48 h), compared with the earlier 0–8-hour period (Figure 1B), may have been attributable to increased concentrations of MUC1 protein at 24 hours and 48 hours, compared with 8 hours (Figure 1C).

Figure 3.

The overexpression of MUC1 suppresses the NTHi-driven release of IL-8. A549 cells were transiently transfected with the pcDNA3.1 empty vector or plasmid encoding MUC1 expression vector for 24 hours before treatment with PBS or NTHi lysate (1:3) for 24 hours. At the end of treatment with NTHi, spent culture media were collected, and the amount of IL-8 was quantified by ELISA. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05. †P > 0.05.

Knockdown of MUC1 Expression Increases NTHi-Driven Release of IL-8

To test the possibility that the increased expression of MUC1 by the NTHi lysate may be responsible for suppression of the lysate-induced release of IL-8, we silenced MUC1 gene expression, using a MUC1-targeting siRNA before treatment with lysate. Subsequently, the amounts of NTHi-induced IL-8 in cell-culture supernatants were measured during the 0- to 24-hour and 24- to 48-hour time periods by the addition of fresh, complete culture medium at the beginning of each treatment period. Theoretically, this procedure should have eliminated the possibility of serum starvation exerting any effect on the production of IL-8, as well as on the feedback inhibition of IL-8 release by cellular products present in the spent medium from the previous treatment period. The initial experiment confirmed greater than 80% inhibition of MUC1 protein concentrations in cell lysates after transfection with the MUC1 siRNA, compared with nontransfected or control siRNA-transfected cells (Figure 4A). As shown in Figure 4B, nontransfected cells or cells transfected with the control siRNA contained significantly decreased NTHi lysate–induced concentrations of IL-8 during the 24- to 48-hour treatment period, compared with the 0- to 24-hour period. By contrast, concentrations of IL-8 during the two time periods were equal in Muc1 siRNA-transfected, lysate-treated cells. These results support the hypothesis that the increased expression of MUC1 at 24 to 48 hours after treatment with NTHi lysate was responsible for the reduced NTHi lysate–induced release of IL-8 during this later time period, compared with the 0- to 24-hour time period.

Figure 4.

Knockdown of MUC1 increases the NTHi-driven release of IL-8. A549 cells were nontransfected or transfected with nontargeting control or MUC1-targeting siRNA (30 nM) for 72 hours before treatment with PBS or NTHi lysate (1:3) in fresh, complete medium for 48 hours. (A) Cells were lysed at the end of treatment with NTHi lysate, and the lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-MUC1 antibody (CT2) or anti–β-tubulin antibody. (B) Spent culture media were collected after 24 hours of treatment with NTHi lysate (0–24-hour sample). Fresh medium containing lysate was added and collected after an additional 24 hours (24–48-hour sample). The amount of IL-8 was quantified by ELISA. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM (n = 5). *P < 0.05.

The NTHi Lysate–Induced Expression of MUC1 Is TNF-α–Dependent

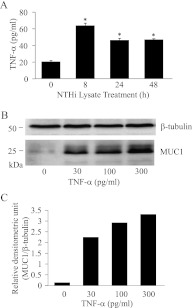

Our previous study showed that the infection of A549 cells by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) increased the expression of MUC1 through a TNF-α–dependent mechanism (13). Therefore, in this experiment we tested the possibility that the NTHi lysate–induced expression of MUC1 was also mediated through TNF-α. Concentrations of TNF-α in the spent media of untreated A549 cells were barely detectable (less than 20 pg/ml), but increased drastically after treatment with NTHi, reaching more than 60 pg/ml at 8 hours (Figure 5A). This amount of TNF-α was sufficient to up-regulate MUC1 in A549 cells (Figures 5B and 5C), suggesting that the NTHi-induced up-regulation of MUC1 (Figure 1C) was attributable to the increased concentrations of TNF-α in the spent medium. For a confirmatory experiment, A549 cells were treated with a soluble form of the TNF receptor 1 (sTNFR1) that binds to and neutralizes the biological activity of TNF-α in solution, thereby inhibiting the ability of the agonist to engage the membrane-bound TNFR. After pretreatment of the cells with sTNFR1, the NTHi lysate was unable to stimulate the increase in MUC1 protein concentrations (Figures 6A and 6B), clearly indicating a major role for TNF-α in the up-regulation of MUC1 during treatment with NTHi.

Figure 5.

NTHi stimulates the release of TNF-α, and TNF-α up-regulates MUC1. (A) A549 cells were serum-starved for 24 hours and treated for the indicated times with NTHi lysate (1:3), and concentrations of TNF-α in culture media were quantified by ELISA. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM (n = 4). *P < 0.05. (B) A549 cells were treated with varying concentrations of human recombinant TNF-α in complete medium for 24 hours, and cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-MUC1 antibody (CT2) or anti–β-tubulin antibody. (C) The density of each MUC1 band was normalized to the density of the corresponding β-tubulin band.

Figure 6.

The NTHi lysate–induced expression of MUC1 is TNF-α–dependent, whereas the NTHi lysate–induced release of IL-8 and activation of NF-κB are TNF-α–independent. (A) A549 cells were untreated or treated with a soluble form of the TNF receptor 1 (sTNFR1; 2.5 nM) for 1 hour before treatment with PBS or NTHi lysate (1:3) for 24 hours. Cells were lysed at the end of treatment with NTHi lysate, and the lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-MUC1 antibody (CT2) or anti–β-tubulin antibody. (B) The density of each MUC1 band was normalized to the density of the corresponding β-tubulin band. (C) A549 cells were treated with NTHi lysate for 24 hours in the presence or absence of sTNFR, and IL-8 in the spent media was quantified by ELISA. (D) Human embryonic kidney 293T cells were transiently transfected with pELAM1-luc, phRL-TK, or pTLR2 for 24 hours. Plasmid encoding 3.1 was used to normalize the total amount of DNA for all transfection reactions. After transfection, cells were treated with NTHi for 24 hours in the presence or absence of sTNFR1 (2.5 nM). At the end of treatment, the cells were lysed for the NF-κB luciferase assay, as described in Materials and METHODS. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05.

The NTHi Lysate–Induced Production of IL-8 Is Mediated through the Activation of TLR2 and NF-κB, but Not of TNF-α

TNF-α was reported to induce the release of IL-8 in some cultured cells, including a human astrocytoma cell line (25) and A549 cells (26). To determine whether the NTHi-induced increase in production of IL-8 was induced by TNF-α, A549 cells were treated with NTHi for 24 hours in the presence or absence of sTNFR1. Figure 6C shows that no difference in the production of IL-8 in the presence or absence of sTNFR1 was evident, suggesting that the NTHi-induced increase in the amount of IL-8 in the spent medium was not mediated by TNF-α. Next, because it is generally well-established that the pathogen-induced production of IL-8 involves the activation of NF-κB through TLR signaling, we tested whether the NTHi-induced production of IL-8 is mediated through TLR2 signaling and the activation of NF-κB, based on the results shown in Figure 2A. We chose HEK293T cells, which are known to be deficient in the expression of TLR2 but are easy to transfect, with little or no toxicity. HEK293T cells were transfected with pTLR2 and pELAM1-luciferase plasmids, the latter for quantifying the activation of NF-κB, and the effect of NTHi was measured by the luciferase assay that reflects the actual level of NF-κB activation. Figure 6D shows that the NTHi-induced activation of NF-κB required the expression of TLR2, but was not affected by the presence of sTNFR1. The involvement of other TLRs cannot be ruled out based on this result, because HEK293T cells do not express most TLRs. Taken together, these results clearly demonstrate that the NTHi-induced release of IL-8 is mediated through TLR2, but is not secondary to an increase in the production of TNF-α. The TNF-α–independent production of IL-8 was reported in both human macrophages and A549 cells treated with Pseudomonas nitrite reductase (27), and in primary human monocytes treated with Neisseria gonorrhoeae (28).

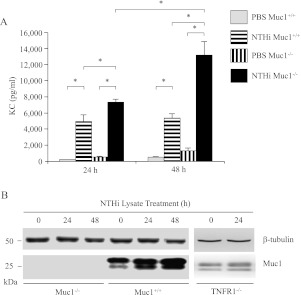

NTHi Lysate Increases the Release of KC and Expression of Muc1 Protein in Primary MTSE Cells

In vitro cultures of human and animal primary tracheobronchial epithelial cells have emerged as alternatives to transformed cell lines grown in an “artificial” environment for the study of airway biology (29). Therefore, key experiments were repeated with freshly isolated, confluent primary MTSE cells from Muc1+/+ and Muc1−/− mice to determine the effects of NTHi lysate on airway inflammation and the expression of Muc1. As shown in Figure 7A, concentrations of KC (the murine orthologue of human IL-8) in culture supernatants of Muc1+/+ and Muc1−/− MTSE cells treated with the lysate were significantly increased, compared with the same cells treated with the PBS vehicle control. Furthermore, concentrations of KC from lysate-treated Muc1−/− mice were significantly greater compared with those from lysate-treated cells from wild-type littermates. In addition, the NTHi lysate increased concentrations of Muc1 protein in Muc1+/+ MTSE cells in a time-dependent manner, but not in primary MTSE cells from TNFR−/− mice (8) (Figure 7B). These observations were consistent with the results obtained using A549 cells.

Figure 7.

NTHi lysate increases the release of keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC) and expression of Muc1 protein in primary murine tracheal surface epithelial (MTSE) cells. Confluent MTSE cells from Muc1+/+, Muc1−/−, and TNFR−/− mice were treated with PBS or NTHi lysate for the indicated time periods. (A) Concentrations of KC in culture media were quantified by ELISA. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05. (B) Cells in A and from TNFR−/− mice were lysed at the end of the treatment periods, and the lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-MUC1 antibody (CT2) or anti–β-tubulin antibody.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that the treatment of human lung epithelial cells with a lysate of NTHi bacteria resulted in an early release of IL-8 (0–8 hours) and a later increase in the expression of MUC1 protein (at 24–48 hours). The increased expression of MUC1, in turn, led to the suppression of IL-8 release at later time points by the cultured cells. Finally, the increased release of IL-8 and expression of MUC1 were blunted in cells transfected with a TLR2 siRNA, and the expression of MUC1 was reduced to baseline in cells pretreated with sTNFR1 before treatment with lysate. These collective results suggest a hypothetical feedback loop model, whereby NTHi activates TLR2 in airway epithelial cells, leading to the increased production of TNF-α and IL-8, which subsequently up-regulate the expression of MUC1 through the activation of TNFR1, resulting in suppressed TLR2 signaling and the decreased production of IL-8. This report is the first, to the best of our knowledge, demonstrating that MUC1 mucin is also involved in controlling the inflammation induced by NTHi, mainly via suppressing TLR2 signaling, which suggests a broad, anti-inflammatory role of MUC1 during airway bacterial infection.

Shuto and colleagues (21) first demonstrated the requirement for TLR2 activation in the NTHi-driven production of IL-8 by HeLa cells. A subsequent report by Galdiero and colleagues (30) revealed that H. influenzae porin, the major outer membrane protein of the bacterium that is responsible for the translocation of hydrophilic molecules across the lipid bilayer, was a TLR2 agonist, and that the treatment of human monocytes or murine macrophages with porin increased the production of TNF-α and IL-6. The present results using A549 cells extend the involvement of TLR2 in the NTHi-stimulated production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines to the airways. A functional role for TLR2 was previously demonstrated in the responses of in vitro human airway epithelial cells to P. aeruginosa (31) and to other respiratory pathogens, including Mycoplasma pneumoniae (32) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (33). Because TLR2 siRNA attenuated the NTHi-stimulated release of IL-8 by only 44%, whereas the NTHi-induced release of IL-8 was almost completely blocked by the overexpression of MUC1, other TLRs are likely activated by pathogen-associated molecular patterns present in NTHi lysate. Previous reports documented that NTHi expresses multiple TLR agonists, including those for TLR3, TLR4, and TLR7 (5, 34–36). In addition, previous observations, that the pre-exposure of mice to NHTi lysate confers protection against challenge with a lethal dose of live Streptococcus pneumonia through the stimulation of the lung innate immune response, are relevant here (37, 38). Nonetheless, our results clearly suggest that TLR2 is the main TLR involved in NTHi-induced inflammatory responses in A549 cells.

TNF-α stimulates the expression of MUC1 in A549 cells (39, 40), human uterine epithelial cells (41), and human prostate cells (42). The molecular mechanism of the TNF-α–induced up-regulation of MUC1 was described elsewhere (39). The NTHi lysate–induced up-regulation of MUC1 requires the interaction of TNF-α and TNFR1. The requirement for TNF-α in the increased expression of MUC1 was also observed in A549 cells infected with RSV (13), and in mice infected with P. aeruginosa (8). Thus, these results suggest that TNF-α may play a key role in controlling inflammation during airway infection, from the initiation phase of bacterial exposure to the final resolution of inflammation. This final resolution likely involves inducing the expression of key anti-inflammatory molecules, such as IL-10 (43) and MUC1 (8, 13). We speculate that the up-regulation of MUC1 in the later stages of airway inflammation may be crucial for counter-regulating the inflammatory process and returning the lungs to a state of normal homeostasis, as recently proposed (12). As a corollary, defective MUC1 protein structure, or altered transcriptional/translational regulation, may play a role in the development of chronic inflammatory lung diseases, such as COPD and cystic fibrosis. Further investigations are underway to address this important question.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that an NTHi lysate induces inflammation in lung epithelial cells, mainly through the activation of TLR2, and the resulting TNF-α up-regulates MUC1, which in turn suppresses TLR2 signaling, thus completing the inflammatory cycle. This report is the first, to the best of our knowledge, showing the anti-inflammatory role of MUC1 during infection with NTHi in lung epithelial cells, via the suppression of TLR2. The molecular mechanism of the MUC1-induced inhibition of TLR signaling is under investigation in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jae-Hyang Lim (Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY) for kindly providing technical help in preparing the NTHi lysate.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant RO1 HL-47125 (K.C.K.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0142OC on September 22, 2011

Yoshiyuki Kyo is currently at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Showa University Northern Yokohama Hospital, Yokohama, Japan.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Murphy TF. Respiratory infections caused by non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2003;16:129–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sethi S, Murphy TF. Infection in the pathogenesis and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2355–2365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moghaddam SJ, Ochoa CE, Sethi S, Dickey BF. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2011;6:113–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erwin AL, Smith AL. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae: understanding virulence and commensal behavior. Trends Microbiol 2007;15:355–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leichtle A, Hernandez M, Pak K, Yamasaki K, Cheng CF, Webster NJ, Ryan AF, Wasserman SI. TLR4-mediated induction of TLR2 signaling is critical in the pathogenesis and resolution of otitis media. Innate Immunol 2009;15:205–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim JH, Ha U, Sakai A, Woo CH, Kweon SM, Xu H, Li JD. Streptococcus pneumoniae synergizes with nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae to induce inflammation via upregulating TLR2. BMC Immunol 2008;9:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hattrup CL, Gendler SJ. Structure and function of the cell surface (tethered) mucins. Annu Rev Physiol 2008;70:431–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi S, Park Y, Koga T, Treloar A, Kim KC. TNF-{alpha} is a key regulator of MUC1, an anti-inflammatory molecule during airway Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2011;44:255–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kato K, Lu W, Kai H, Kim KC. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase is activated by MUC1 but not responsible for MUC1-induced suppression of Toll-like receptor 5 signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007;293:L686–L692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu W, Hisatsune A, Koga T, Kato K, Kuwahara I, Lillehoj EP, Chen W, Cross AS, Gendler SJ, Gewirtz AT, et al. Cutting edge: enhanced pulmonary clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by Muc1 knockout mice. J Immunol 2006;176:3890–3894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ueno K, Koga T, Kato K, Golenbock DT, Gendler SJ, Kai H, Kim KC. MUC1 mucin is a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor signaling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008;38:263–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim KC, Lillehoj EP. MUC1 mucin: a peacemaker in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008;39:644–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y, Dinwiddie DL, Harrod KS, Jiang Y, Kim KC. Anti-inflammatory effect of MUC1 during respiratory syncytial virus infection of lung epithelial cells in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2010;298:L558–L563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu W, Lillehoj EP, Kim KC. Effects of dexamethasone on MUC5AC mucin production by primary airway goblet cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005;288:L52–L60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shuto T, Imasato A, Jono H, Sakai A, Xu H, Watanabe T, Rixter DD, Kai H, Andalibi A, Linthicum F, et al. Glucocorticoids synergistically enhance nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae–induced Toll-like receptor 2 expression via a negative cross-talk with p38 MAP kinase. J Biol Chem 2002;277:17263–17270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuwahara I, Lillehoj EP, Lu W, Singh IS, Isohama Y, Miyata T, Kim KC. Neutrophil elastase induces IL-8 gene transcription and protein release through p38/NF-{kappa}B activation via EGFR transactivation in a lung epithelial cell line. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;291:L407–L416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imasato A, Desbois-Mouthon C, Han J, Kai H, Cato AC, Akira S, Li JD. Inhibition of p38 MAPK by glucocorticoids via induction of MAPK phosphatase–1 enhances nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae–induced expression of Toll-like receptor 2. J Biol Chem 2002;277:47444–47450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komatsu K, Jono H, Lim JH, Imasato A, Xu H, Kai H, Yan C, Li JD. Glucocorticoids inhibit nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae–induced MUC5AC mucin expression via MAPK phosphatase–1–dependent inhibition of p38 MAPK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008;377:763–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim JH, Jono H, Koga T, Woo CH, Ishinaga H, Bourne P, Xu H, Ha UH, Xu H, Li JD. Tumor suppressor CYLD acts as a negative regulator for non-typeable Haemophilus influenza–induced inflammation in the middle ear and lung of mice. PLoS ONE 2007;2:e1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moghaddam SJ, Clement CG, De la Garza MM, Zou X, Travis EL, Young HW, Evans CM, Tuvim MJ, Dickey BF. Haemophilus influenzae lysate induces aspects of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotype. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008;38:629–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shuto T, Xu H, Wang B, Han J, Kai H, Gu XX, Murphy TF, Lim DJ, Li JD. Activation of NF-kappa B by nontypeable Hemophilus influenzae is mediated by Toll-like receptor 2–TAK1–dependent NIK-IKK alpha/beta-I kappa B alpha and MKK3/6-p38 MAP kinase signaling pathways in epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:8774–8779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang B, Cleary PP, Xu H, Li JD. Up-regulation of interleukin-8 by novel small cytoplasmic molecules of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae via p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways. Infect Immun 2003;71:5523–5530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu F, Xu Z, Zhang R, Wu Z, Lim JH, Koga T, Li JD, Shen H. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae induces COX-2 and PGE2 expression in lung epithelial cells via activation of p38 MAPK and NF-kappa B. Respir Res 2008;9:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin LD, Rochelle LG, Fischer BM, Krunkosky TM, Adler KB. Airway epithelium as an effector of inflammation: molecular regulation of secondary mediators. Eur Respir J 1997;10:2139–2146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kasahara T, Mukaida N, Yamashita K, Yagisawa H, Akahoshi T, Matsushima K. IL-1 and TNF-alpha induction of IL-8 and monocyte chemotactic and activating factor (MCAF) mRNA expression in a human astrocytoma cell line. Immunology 1991;74:60–67 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brasier AR, Jamaluddin M, Casola A, Duan W, Shen Q, Garofalo RP. A promoter recruitment mechanism for tumor necrosis factor–alpha–induced interleukin-8 transcription in Type II pulmonary epithelial cells: dependence on nuclear abundance of Rel A, NF-kappaB1, and c-Rel transcription factors. J Biol Chem 1998;273:3551–3561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sar B, Oishi K, Matsushima K, Nagatake T. Induction of interleukin 8 (IL-8) production by Pseudomonas nitrite reductase in human alveolar macrophages and epithelial cells. Microbiol Immunol 1999;43:409–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patrone JB, Bish SE, Stein DC. TNF-alpha–independent IL-8 expression: alterations in bacterial challenge dose cause differential human monocytic cytokine response. J Immunol 2006;177:1314–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fulcher ML, Gabriel S, Burns KA, Yankaskas JR, Randell SH. Well-differentiated human airway epithelial cell cultures. Methods Mol Med 2005;107:183–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galdiero M, Galdiero M, Finamore E, Rossano F, Gambuzza M, Catania MR, Teti G, Midiri A, Mancuso G. Haemophilus influenzae porin induces Toll-like receptor 2–mediated cytokine production in human monocytes and mouse macrophages. Infect Immun 2004;72:1204–1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soong G, Reddy B, Sokol S, Adamo R, Prince A. TLR2 is mobilized into an apical lipid raft receptor complex to signal infection in airway epithelial cells. J Clin Invest 2004;113:1482–1489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chu HW, Jeyaseelan S, Rino JG, Voelker DR, Wexler RB, Campbell K, Harbeck RJ, Martin RJ. TLR2 signaling is critical for Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced airway mucin expression. J Immunol 2005;174:5713–5719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Regueiro V, Moranta D, Campos MA, Margareto J, Garmendia J, Bengoechea JA. Klebsiella pneumoniae increases the levels of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in human airway epithelial cells. Infect Immun 2009;77:714–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakai A, Koga T, Lim JH, Jono H, Harada K, Szymanski E, Xu H, Kai H, Li JD. The bacterium, nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae, enhances host antiviral response by inducing Toll-like receptor 7 expression: evidence for negative regulation of host anti-viral response by CYLD. FEBS J 2007;274:3655–3668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teng F, Slavik V, Duffy KE, San Mateo L, Goldschmidt R. Toll-like receptor 3 is involved in airway epithelial cell response to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Cell Immunol 2010;260:98–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wieland CW, Florquin S, Maris NA, Hoebe K, Beutler B, Takeda K, Akira S, van der Poll T. The MyD88-dependent, but not the MyD88-independent, pathway of TLR4 signaling is important in clearing nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae from the mouse lung. J Immunol 2005;175:6042–6049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clement CG, Evans SE, Evans CM, Hawke D, Kobayashi R, Reynolds PR, Moghaddam SJ, Scott BL, Melicoff W, Adachi E, et al. Stimulation of lung innate immunity protects against lethal pneumococcal pneumonia in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:1322–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clement CG, Tuvim MJ, Evans CM, Tuvin DM, Dickey BF, Evans SE. Allergic lung inflammation alters neither susceptibility to Streptococcus pneumoniae infection nor inducibility of innate resistance in mice. Respir Res 2009;10:70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koga T, Kuwahara I, Lillehoj EP, Lu W, Miyata T, Isohama Y, Kim KC. TNF-alpha induces MUC1 gene transcription in lung epithelial cells: its signaling pathway and biological implication. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007;293:L693–L701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuwahara I, Lillehoj EP, Koga T, Isohama Y, Miyata T, Kim KC. The signaling pathway involved in neutrophil elastase stimulated MUC1 transcription. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2007;37:691–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thathiah A, Brayman M, Dharmaraj N, Julian JJ, Lagow EL, Carson DD. Tumor necrosis factor alpha stimulates MUC1 synthesis and ectodomain release in a human uterine epithelial cell line. Endocrinology 2004;145:4192–4203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Connor JC, Julian J, Lim SD, Carson DD. MUC1 expression in human prostate cancer cell lines and primary tumors. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2005;8:36–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wanidworanun C, Strober W. Predominant role of tumor necrosis factor–alpha in human monocyte IL-10 synthesis. J Immunol 1993;151:6853–6861 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.