Abstract

Of the diagnostic features of autism, relatively little research has been devoted to restricted and repetitive behavior, particularly topographically complex forms of restricted and repetitive behavior such as rigidity in routines or compulsive-like behavior (e.g., arranging objects in patterns or rows). Like vocal or motor stereotypy, topographically complex forms of restricted and repetitive behavior may be associated with negative outcomes such as interference with skill acquisition, negative social consequences, and severe problem behavior associated with interruption of restricted and repetitive behavior. In the present study, we extended functional analysis methodology to the assessment and treatment of arranging and ordering for 3 individuals with an autism spectrum disorder. For all 3 participants, arranging and ordering was found to be maintained by automatic reinforcement, and treatments based on function reduced arranging and ordering.

Keywords: arranging and ordering, autism, cleaning, completeness, compulsive behavior, washing, functional analysis, higher level restricted and repetitive behavior

Compared with the other diagnostic features of autism, little research has been devoted to restricted and repetitive behavior (Bodfish, 2004; South, Ozonoff, & McMahon, 2005; Turner, 1999). In particular, topographically complex forms of restricted and repetitive behavior (e.g., rigidity in routines or compulsive-like1 behavior such as arranging objects in patterns or rows) are understudied (Bodfish, 2004; Turner, 1999). This lack of research is problematic because, like vocal or motor stereotypy, more complex forms of restricted and repetitive behavior may be associated with negative outcomes such as interference with skill acquisition (e.g., Dunlap, Dyer, & Koegel, 1983), negative social consequences (Jones, Wint, & Ellis, 1990), and severe problem behavior associated with its interruption (Cuccaro et al., 2003; Flannery & Horner, 1994; Turner, 1999). In fact, several researchers have demonstrated a functional relation between aggression and disruption and access to the opportunity to engage in compulsive-like behavior with individuals with autism (e.g., Hausman, Kahng, Farrell, & Mongeon, 2009; Kuhn, Hardesty, & Sweeney, 2009) and other developmental disabilities (e.g., Murphy, Macdonald, Hall, & Oliver, 2000).

As a means of distinguishing between forms of restricted and repetitive behavior that vary in topographical complexity, Turner (1999) suggested subdividing restricted and repetitive behavior into higher level and lower level classes. According to Turner, higher level restricted and repetitive behavior includes complex behavior such as circumscribed interests (e.g., preoccupation with serial numbers on electronics), rigid and invariant routines (e.g., dressing, eating, or playing in a particular pattern), and arranging and ordering (e.g., lining things up in patterns or rows); lower level restricted and repetitive behavior includes less complex forms of stereotypy such as repetitive motions (e.g., hand flapping) and repetitive manipulation of objects (e.g., object spinning). Several hypotheses have been proposed as to the function of higher level restricted and repetitive behavior. For example, this type of behavior has been said to be evidence of a “need for sameness” (e.g., Kanner, 1943; Prior & MacMillan, 1973) or an inherent lack of behavioral flexibility (Green et al., 2006), yet few studies have sought to understand environmental variables that contribute to this apparent need for sameness or lack of behavioral flexibility (cf. Flannery & Horner, 1994, who assessed the role of predictability on problem behavior associated with disruption of routines). Further, even though individuals with an autism spectrum disorder are commonly described as engaging in both classes of restricted and repetitive behavior, we could not locate any studies in the autism literature that sought to treat problematic forms of higher level restricted and repetitive behavior.

One productive approach to addressing problem behavior is to develop treatments based on its function. Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, and Richman (1982/1994) developed a comprehensive functional analysis to test behavioral sensitivity to three main types of reinforcement contingencies: social positive, social negative, and automatic. Originally applied to the assessment and treatment of self-injurious behavior, functional analyses since have been applied to the study of a wide range of problem behavior, including aggression (e.g., Fisher et al., 1993), pica (e.g., Piazza et al., 1998), property destruction (e.g., Fisher, Lindauer, Alterson, & Thompson, 1998), and lower level restricted and repetitive behavior, such as motor stereotypy (e.g., Kennedy, Meyer, Knowles, & Shukla, 2000). In addition to demonstrating the generality of functional analysis methodology, these studies demonstrated how functional analyses can be adjusted to allow the assessment of behavior other than self-injury.

To date, no published studies have used functional analysis methodology to analyze higher level restricted and repetitive behavior. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to extend the functional analysis model to the assessment and treatment of arranging and ordering and other compulsive-like behavior (e.g., completeness2 and washing and cleaning) for three individuals with an autism spectrum disorder. Arranging and ordering was selected as the topography of interest based on results from an unpublished survey that we conducted (data available from the first author), which identified arranging and ordering as one of the most problematic forms of higher level repetitive behavior for the population sampled (14% of 102 students with an autism spectrum disorder reportedly engaged in arranging and ordering that was rated as severely problematic). Participants in this study represent those students for whom the frequency and severity of their arranging and ordering and other related compulsive-like behavior warranted intervention.

GENERAL METHOD

Participants

All three participants attended a specialized school and residential program for individuals with autism and other developmental disabilities.

Jim was a 15-year-old boy who had been diagnosed with pervasive developmental disorder (not otherwise specified). He followed simple instructions and spoke in one- to three-word sentences but with a limited vocabulary. His compulsive-like behavior included arranging and ordering (e.g., aligning objects or furniture against other objects or surfaces) and completeness (e.g., insisting that items such as drawers or doors remained completely closed; see below for operational definitions). Jim also engaged in high rates of lower level restricted and repetitive behavior including vocal stereotypy and repetitive touching or tapping of items and surfaces. Collectively, his restricted and repetitive behavior occurred at such a high rate that his teachers described him as constantly moving or engaging in some form of restricted and repetitive behavior. Teachers reported that his behavior was difficult to interrupt or redirect, that the severity of this behavior made it difficult for them to complete academic work with him, and that he would sometimes push his teacher out of the way to arrange and order items.

Ross was a 13-year-old boy who had been diagnosed with autism. He followed instructions and spoke in one- to three-word sentences. His compulsive-like behavior included arranging and ordering, completeness, and washing and cleaning (e.g., picking at lint or loose threads; see below for operational definitions). Teachers reported that Ross excessively straightened or organized items (e.g., on shelves, in closets, or in refrigerators) or fixed anything that was out of place (e.g., a loose thread on someone's shirt or a book placed upside down on a bookshelf). His arranging and ordering often caused delays when transitioning to the next scheduled activity. For example, when retrieving a drink from the refrigerator during dinner, Ross often arranged items in the refrigerator until someone interrupted him. Among the more problematic forms of Ross's arranging and ordering was his arranging of items in trash bins, which posed health risks. His behavior also extended to other people (e.g., fixing buttons or loose threads on others' clothing), which teachers reported could cause problems if it involved another student. Picking of loose threads on his own clothing sometimes resulted in large holes in his clothing. In addition, interruption of compulsive-like behavior sometimes resulted in minor self-injurious behavior, property destruction, tantrums, or vocal perseveration on the item until it was fixed.

Christie was a 15-year-old girl who had been diagnosed with autism. She followed simple instructions and spoke using two- to four-word sentences. Her compulsive-like behavior included arranging and ordering of furniture and other items (e.g., magazines or leisure items). Teachers reported that interrupting or blocking arranging and ordering of furniture or other items often resulted in aggression or self-injurious behavior. Among the most problematic forms of arranging and ordering was her arranging of large pieces of furniture, which could be dangerous should, for example, the furniture become unstable and fall.

Response Measurement and Interobserver Agreement

Data were collected on arranging and ordering for all participants. When applicable, data also were collected on other types of higher level restricted and repetitive behavior listed on the compulsive subscale of the Repetitive Behavior Scale–Revised (RBS-R; developed by Bodfish, Symons, Parker, & Lewis, 2000; also see Bodfish, Symons, & Lewis, 1999), including completeness (Jim and Ross) and washing and cleaning (Ross only). Response definitions from the RBS-R were modified based on information gathered from interviews and observations to encompass each individual's specific form of the target behavior.

Arranging and ordering was defined as moving objects from one location to another (when not related to retrieving or putting away leisure or academic materials or interacting with items as the manufacturer intended); aligning objects against another surface such as a wall, corner, or another object; and lining up or stacking objects when doing so was not the intended purpose for those objects (e.g., dominos or blocks). Arranging and ordering was recorded using a duration measure for Ross and Christie. However, because Jim repeatedly aligned the same object in the same manner in rapid succession (e.g., placing the trash bin in the corner of the room four times in a row within 4 s), his arranging and ordering was measured according to the frequency of episodes. Specifically, a new episode was scored after a 1-s pause from the last episode or when he made contact with a new item. For Christie, the functional analysis included both arranging and ordering of furniture and other items such as books and toys. However, because of the difference in the severity of the problem across topographies, arranging and ordering of furniture was recorded separately from other items for all subsequent analyses.

Completeness was defined as closing drawers, closing books, and placing tops on containers (not including instances during which it would be natural to do so, such as after retrieving an item from a drawer or reading a book). Washing and cleaning was defined as picking at lint or loose threads, picking up trash from the floor or other surfaces, and wiping surfaces with one's hand. Completeness and washing and cleaning were recorded using a frequency measure.

When applicable during treatment evaluations, data also were collected on item engagement, prompts, response blocking or interruption, and product replacement. Duration of item engagement was defined differently for each item but generally included item contact plus appropriate manipulation (not including stereotypic manipulation of items). Response blocking or interruption (hereafter referred to as response blocking) was scored when the experimenter placed her hand between the participant and the materials involved in the target behavior. To accommodate responding during response-blocking conditions, response definitions for each target behavior included blocked attempts to engage in that response.

Duration data were summarized as percentage duration per session by dividing the number of seconds in which the target response occurred by the total number of seconds in a session (600 s) and then multiplying the quotient by 100%. Frequency data were summarized as responses per minute by dividing the frequency of the target response in a session by the total number of minutes in a session (10 min).

Sessions were videotaped so that they could be scored at a later time. Data during all analyses and treatment evaluations were collected on handheld computers. A second observer independently scored data during a minimum of 33% of sessions, distributed equally across conditions. Interobserver agreement for duration and frequency measures was determined by partitioning sessions into 10-s bins and comparing data collectors' observations on an interval-by-interval basis. For each interval, the smaller number (duration or frequency) was divided by the larger number. The quotient then was multiplied by 100% and averaged across all intervals. Intervals during which both data collectors agreed that the target behavior did not occur were factored into the above equation as 100% agreement for that interval. Mean agreement scores for Jim's experimental analyses were 93% (range, 67% to 100%) for arranging and ordering, 97% (range, 89% to 100%) for completeness, 82% (range, 68% to 92%) for item engagement, 94% (range, 87% to 100%) for prompts, and 97% (range, 93% to 100%) for response blocking. Mean agreement scores for Ross's experimental analyses were 90% (range, 67% to 100%) for arranging and ordering, 99.5% (range, 95% to 100%) for completeness, 97% (range, 72% to 100%) for washing and cleaning, 98% (range, 85% to 100%) for item engagement, and 99% (range, 97% to 100%) for response blocking. Mean agreement scores for Christie's experimental analyses were 94% (range, 76% to 100%) for arranging and ordering, 95% (range, 83% to 100%) for item engagement, and 92% (range, 77% to 100%) for prompts.

FUNCTIONAL ANALYSES

Given the paucity of studies that have addressed arranging and ordering in autism, we began by gathering information regarding the topography of interest via teacher interviews and naturalistic observations (data available from the first author). This information was used to arrange experimental analyses such that the types of antecedent and consequent events programmed matched those typically encountered during naturally occurring conditions (thereby increasing the ecological validity of our experimental analyses; Hanley, Iwata, & McCord, 2003). Operational definitions and session materials were also informed by interviews and observations in natural settings. All sessions lasted 10 min.

Comprehensive Functional Analysis

Assessments for each participant began with a functional analysis of arranging and ordering and other related compulsive-like behavior.

Settings and materials

The setting in which the functional analysis was conducted varied for each participant. Sessions for Jim and Ross were conducted in session rooms (1.5 m by 3 m). Each of the session rooms contained a desk, two chairs, a trash bin, a set of drawers, several notebooks and magazines, two stacks of mismatched cups, a silverware tray with unorganized plastic silverware, academic materials (e.g., money, colored cards), and at least one container of items. On the desk was a pencil holder with pencils and several other items such as a ruler, cups, or a water bottle. Items in the session room were intentionally unaligned (e.g., the trash bin was near the wall but placed at an angle and the desk was against the wall but with approximately 3 cm of space between the desk and wall), mismatched (e.g., several plastic blocks were placed in a bin of wooden blocks), placed outside their bins, or were incomplete (e.g., magazines and notebooks were left open and drawers and the top of the container were left slightly ajar). This was done to allow multiple opportunities to arrange and order or complete items. For Ross, we added enough items (e.g., crumpled paper, cups, napkins) to the trash bin to fill it to the rim, three loose threads placed on various parts of the experimenter's clothing, and a plant (Ross arranged and ordered the dirt, stems, and leaves of plants).

Sessions for Christie were conducted in the living room of her residence. The room contained a locked TV cabinet, two couches, an end table, a wooden desk and chair, two bookshelves, two locked cabinets, a treadmill, an area carpet (1.8 m by 2.5 m), a table (0.6 m by 1.8 m) with various items (e.g., magazines and dolls) on it, a basket of toys, a large bouncy ball, and four magazines on the floor. Videos were played on the TV during all sessions to approximate conditions under which arranging and ordering occurred during naturalistic observations. No other students were present during sessions.

The experimenter developed the initial arrangement of furniture and materials for each participant to permit numerous opportunities to observe the target behavior. Although the number of items that could be completed or washed and cleaned were limited compared to those items that could be arranged and ordered, materials (aside from leisure items in the attention and control condition) were held constant across sessions to ensure equal opportunity to engage in target behavior across sessions. It also should be noted that participants were never observed to produce an entirely orderly environment prior to the end of a session, which suggests that the opportunity to engage in target behavior was present throughout each session.

Procedure

Functional analysis procedures were similar to those described by Iwata et al. (1982/1994); however, antecedent and consequent events were adjusted to accommodate information gathered from interviews and naturalistic observations. Three test conditions (attention, escape, and no interaction) and a control condition were alternated in a multielement design. Different-colored discriminative stimuli (i.e., poster board, t-shirt, or tablecloth) were paired with each condition of the functional analysis to facilitate discrimination between contingencies that operated in different conditions (Conners et al., 2000).

In the attention condition, two low-preference leisure items were available while the experimenter pretended to be occupied reading a magazine (leisure items were identified using paired-item preference assessment procedures described by Fisher et al., 1992; data available from the first author). Contingent on target behavior, the experimenter provided attention on a fixed-ratio (FR) 1 schedule. Based on narrative records from naturalistic observations, attention for Jim and Ross took the form of comments about the ordering (e.g., “It's fine Jim, you don't need to fix it.”) or reprimands (e.g., “Stop!” “Leave it.”). Attention for Christie took the form of vocal reprimands (e.g., “Christie, stop!”) and statements of concern (e.g., “Careful, it could fall on you. You could hurt yourself.”).

An escape condition was included to identify whether the targeted restricted and repetitive behavior functioned to postpone or terminate a nonpreferred activity. Demands were selected based on interviews and descriptive data and were delivered using three-step guided compliance (i.e., vocal, gesture or model, and physical prompts, with 5 s between each prompt). Contingent on target behavior, the experimenter turned away from the participant and provided a 30-s break from the task. Demand materials were removed only when they were not involved in target behavior. For Jim and Ross, an avoidance contingency also was included, in which the escape interval was extended by 30 s contingent on a target behavior (e.g., Iwata et al. 1982/1994). The inclusion of an avoidance contingency was consistent with naturalistic observations, during which Jim and Ross sometimes engaged in compulsive-like behavior prior to transitioning to a new location and activity, which may have delayed the onset of the next activity. In such cases, stimuli other than an explicit instruction may have signaled the onset of a new activity (e.g., when a teacher said to another teacher, “We're on our way to the academic classroom.”).

Although interviews and descriptive data for Christie did not suggest that arranging and ordering occurred in the context of demands, we included an escape condition because escape is the most common maintaining variable for other problem behavior of individuals with developmental disabilities and related disorders (e.g., Iwata, Pace, Dorsey, et al., 1994). To ensure that there was an opportunity to arrange furniture, we included demands that allowed Christie to move about the room such as physical education (e.g., jumping jacks) and clean-up tasks (e.g., wiping windows). An avoidance contingency was not included in the escape condition for Christie because, unlike for Jim and Ross, naturalistic observations did not suggest that arranging and ordering may have served to delay the onset of demands (e.g., arranging and ordering was not observed to occur following the delivery of instructions).

We included a no-interaction condition, during which the experimenter was in the room but did not interact with the participant, to identify whether the target restricted and repetitive behavior persisted in the absence of social contingencies. A no-interaction condition was included instead of an alone condition for safety reasons and because some target responses required the presence of another person (e.g., removing threads from other people's clothing).

In the control condition, no demands were presented and attention was delivered every 30 s and contingent on requests for attention (e.g., vocal requests for tickles). However, if a target behavior occurred immediately prior to a scheduled attention delivery, attention was delayed for 5 s. In addition, two highly preferred leisure items, selected based on the results of a paired-item preference assessment (Fisher et al., 1992), were continuously available.

Experimental conditions were conducted in a fixed sequence (i.e., no interaction, attention, control, and escape; e.g., Iwata, Pace, Dorsey, et al., 1994). We conducted several consecutive no-interaction sessions at the end of the analysis to determine whether responding would persist in the absence of social contingencies, providing further support for an automatic function (e.g., Vollmer, Marcus, & LeBlanc, 1994).

Results and discussion

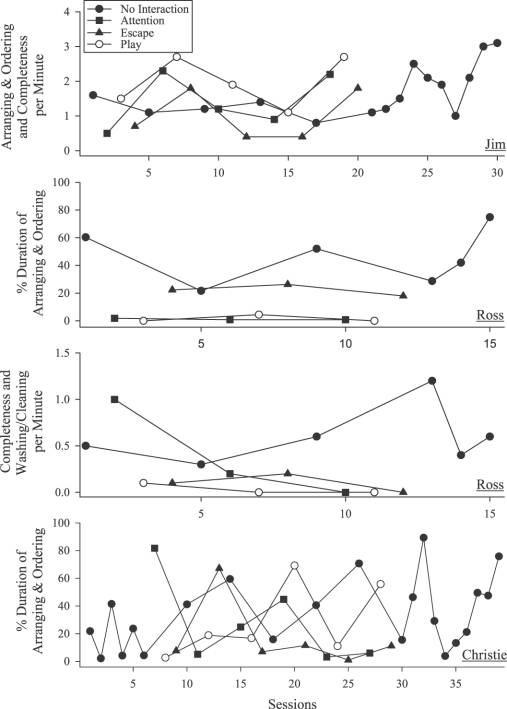

Functional analysis results for all three participants are depicted in Figure 1. Jim's levels of responding (top panel) were variable across all conditions and persisted across a series of no-interaction sessions, suggesting that his arranging and ordering and completeness were maintained by automatic reinforcement.

Figure 1.

Functional analysis data for Jim (top), Ross (second and third panels), and Christie (bottom).

Ross's levels of arranging and ordering (second and third panels) were higher in the no-interaction and escape conditions and persisted across a series of repeated no-interaction conditions, suggesting that his arranging and ordering was maintained by automatic reinforcement and escape from demands. Higher levels of completeness and washing and cleaning occurred in the no-interaction condition, suggesting that completeness and washing and cleaning likely were maintained by automatic reinforcement.

Christie's levels of arranging and ordering (bottom panel) were variable across all conditions, except the escape condition, which was relatively low and stable. In addition, responding persisted across both series of no-interaction sessions, suggesting that her arranging and ordering was maintained by automatic reinforcement.

Follow-Up Functional Analyses

Escape analysis (Ross)

Ross's functional analysis suggested that arranging and ordering was maintained by both automatic reinforcement and escape from demands. However, it is possible that responding in the escape condition was not due to the avoidance or escape contingency but, instead, to the lack of alternative stimulation available during avoidance or escape intervals (Kuhn, DeLeon, Fisher, & Wilke, 1999). If so, lower levels of responding may have been observed in the control and attention conditions because highly preferred leisure items in the control condition competed with arranging and ordering, and vocal comments in the attention condition functioned as punishment. Thus, we conducted an analysis similar to that conducted by Kuhn et al. (1999) in which a function-based treatment that was matched to one function but not the other was used to clarify whether arranging and ordering was maintained by both automatic reinforcement and escape from demands or by automatic reinforcement alone.

Setting and design

Ross's escape analysis was conducted using a multiple baseline design across settings. The first setting was the same as the functional analysis. The second setting was a classroom equipped with a table (1.5 m by 1.5 m), six chairs, a computer and desk, three bookshelves containing a variety of books and leisure items, a locked toy cabinet, a set of drawers left slightly ajar, a plant, and a trash bin filled with clean items. As in the functional analysis, items were mismatched, placed outside their bins, or unaligned. In addition, three loose threads were placed on the experimenter's clothing.

No interaction and escape

The no-interaction and escape conditions from Ross's functional analysis served as the baseline for the escape analysis in the first setting. Baseline in the second setting was the same as the no-interaction condition of the function analysis.

Response blocking and blocking plus escape

Response blocking was added to both no-interaction and escape conditions in an attempt to eliminate the automatic reinforcer. If target behavior also was maintained by escape from demands, it would persist in the escape condition when attempts to engage in target behavior resulted in escape but not access to the automatic reinforcer. During response blocking, the experimenter blocked attempts to engage in a target behavior or interrupted a target behavior after initiation of the response. If Ross successfully displaced an item (which rarely occurred), the item was replaced immediately in its previous position. The response blocking plus escape condition was similar to the escape condition of the functional analysis except that the target behavior was blocked or interrupted; attempts to engage in the target behavior continued to result in a 30-s break from demands or a 30-s delay to the onset of the next demand.

Results and discussion

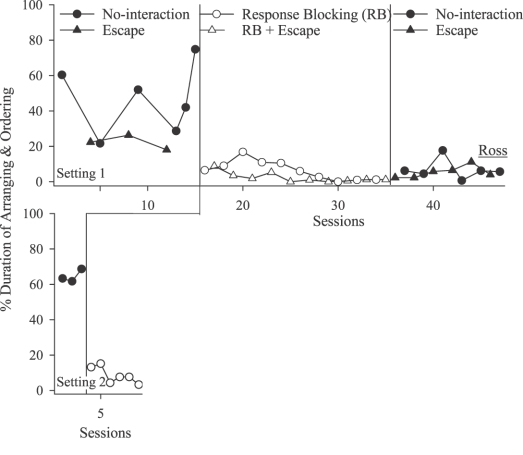

Figure 2 shows the results of Ross's escape analysis. When the automatic reinforcer was eliminated, levels of arranging and ordering decreased across both response blocking and blocking plus escape conditions. That is, responding was not maintained when escape was provided as a reinforcer, suggesting that arranging and ordering likely was maintained by automatic reinforcement alone. An alternative explanation for the decrease in responding observed in the escape analysis, however, is that response blocking may have functioned as a punisher. Indeed, this alternate hypothesis is supported by the fact that responding did not recover to baseline levels in Setting 1 (third phase, top panel). The difficulty in determining what process (extinction or punishment) was responsible for the decrease in responding and the fact that responding did not recover to baseline levels in the reversal in Setting 1 are both limitations of our escape analysis.

Figure 2.

The percentage duration of arranging and ordering during Ross's escape analysis. Data from his functional analysis were used as the initial phase in Setting 1 (top). The percentage duration of arranging and ordering in Setting 2 is depicted in the bottom panel.

Process versus product analysis (Christie)

We conducted a process versus product analysis with Christie to identify the nature of the automatic reinforcer that maintained arranging and ordering of furniture. There appeared to be consistencies in the direction in which furniture was moved during functional analysis sessions. Thus, we hypothesized that arranging furniture may have been maintained by some property of its final placement (i.e., the product of arranging and ordering) rather than the opportunity to arrange and order the furniture (i.e., the process of arranging and ordering). If the final placement of furniture was the reinforcer, then additional treatment options that did not involve physical contact would be available (e.g., maintaining furniture in a preferred placement or replacing furniture contingent on arranging and ordering). This was important, because teachers hesitated to physically block Christie because it reportedly evoked or elicited aggression.

Setting

Sessions were conducted in the same room as Christie's functional analysis.

Procedure

The process versus product analysis involved a comparison of two antecedent conditions: furniture arranged according to the original arrangement used in all previous sessions (original arrangement condition) or furniture arranged according to a preferred arrangement (preferred product condition). No differential consequences were provided contingent on arranging and ordering during either condition.

Preferred product probes

Prior to beginning the process versus product analysis, we conducted five 50-min probes during which no differential consequences were provided for arranging and ordering and the experimenter honored all of Christie's requests for help in moving the furniture. During these probes, Christie consistently arranged furniture such that the carpet was in the corner by the TV cabinet, and the couches, bookshelf, table, desk, chair, and bouncy ball were placed tightly together in a cluster around the TV cabinet.

Original arrangement

This condition served as the comparison (or control) condition. The furniture arrangement at the start of session was the same as the functional analysis.

Preferred product placement

The preferred product condition served as the test condition. If arranging and ordering was maintained by access to a product, then little to no arranging and ordering should occur when furniture was prearranged according to Christie's preferred furniture placement. On the other hand, if arranging and ordering was maintained by the process of arranging and ordering, then levels of arranging and ordering would be similar to levels in the original arrangement condition.

Prior to preferred product sessions, furniture was arranged according to information provided by the 50-min probes. In addition, Christie was given three 15-s opportunities to request adjustments. This was done to accommodate small adjustments (e.g., aligning the corners of the couches) as well as to detect large changes in preference prior to the start of session. Specifically, the experimenter asked Christie, “Where would you like the furniture?” and pointed to several pieces of furniture while asking, “Stay here or move?” If Christie requested that something be moved, she was taken to another room while the experimenter arranged the furniture according to her request. This was done in the event that watching the furniture being moved was reinforcing. If Christie requested large changes to the arrangement of the furniture (e.g., moving the TV cabinet from one side of the living room to the other), sessions were terminated and a 50-min preferred product probe was conducted. This occurred once, before Session 15. Sessions were never conducted after preferred product probes in case the provision of 50-min access to arranging and ordering served as an abolishing operation.

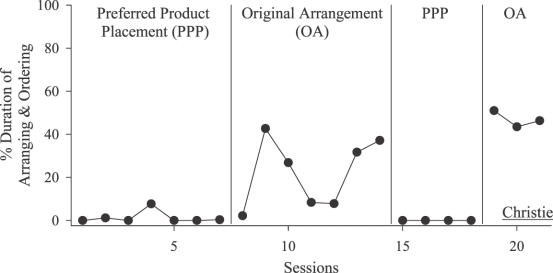

Results and discussion

Figure 3 shows the results from Christie's process versus product analysis. Levels of arranging and ordering were consistently higher in the original arrangement condition. Because this analysis involved antecedent manipulations, the nature of the automatic reinforcer could be inferred based on levels of responding that would be expected in the presence and absence of an establishing operation for access to a final product. The fact that Christie did not arrange furniture in the preferred product condition suggests that the establishing operation for arranging and ordering furniture had been eliminated and that the product and not the process of arranging and ordering was the reinforcer.

Figure 3.

The percentage duration of arranging and ordering of furniture across preferred product placement and original arrangement conditions for Christie's process versus product analysis.

TREATMENT EVALUATION

Results from functional analyses were used to develop function-based treatments for each of the three participants. Due to variations in procedures across participants, procedures are presented individually for each participant. All sessions were 10 min.

Settings

Sessions for Jim and Christie were conducted in the same room as their functional analyses. Due to the limited availability of settings used during previous analyses, Ross's treatment evaluation was conducted in the recreational room of his residence. The arrangement of materials in the room was similar to previous analyses except that a plant was not present, and instead of loose threads on the experimenter's clothing, four small pieces of paper were scattered across the floor (picking up trash from the floor was scored as washing and cleaning).

Jim

Baseline

The series of no-interaction sessions at the end of Jim's functional analysis served as the initial baseline for his treatment evaluation.

Matched items

This condition was included to identify whether providing Jim with appropriate materials to arrange and order and complete would decrease inappropriate forms of arranging and ordering and completeness. Sessions were similar to baseline except that two matched items were continuously available. A preliminary competing items assessment (e.g., Piazza, Adelinis, Hanley, Goh, & Delia, 2000) was not conducted because Jim typically banged, ripped, or threw leisure items during informal probes. Instead, matched items were selected based on whether they (a) could be arranged in a manner that minimized inappropriate play (e.g., by fastening items to a table) and (b) were likely to produce automatic reinforcement similar to that produced by arranging and ordering or completeness. Matched items included a learning cube and a toy bin. The learning cube (0.3 m by 0.3 m by 0.3 m) contained rollercoaster beads, a sliding peg maze, an abacus, and a xylophone. The toy bin (0.5 m by 0.5 m by 0.4 m) contained a variety of leisure items (e.g., monster truck and ball) as well as materials that could be arranged and ordered or completed but on a smaller, more contained scale (e.g., miniature drawers and containers). The learning cube was secured to the table using bungee cords, and items in the bin were attached by strings so that Jim could not throw or destroy them.

Matched items plus prompts

Because Jim did not engage with the leisure items in the matched items condition, we conducted separate training sessions to teach appropriate item engagement (data available from the first author). Prompts then were included within the formal treatment evaluation to test their effect on arranging and ordering and completeness. This condition was similar to the matched items condition, except that prompts were provided every 15 s unless Jim already was engaged with a matched item. Thus, the number of prompts per session varied. Specifically, if he was not engaged with an item at the end of a 15-s interval, the experimenter delivered a vocal and model prompt (e.g., “Let's put all the blue pegs over here” while modeling the action). If Jim did not engage with a matched item within 2 s of the vocal and model prompt, the experimenter provided the least amount of physical guidance necessary to initiate item engagement. A voice recorder signaled the 15-s intervals.

Matched items plus prompts plus response blocking

A response-blocking component was added to disrupt the relation between arranging and ordering and completeness and the resulting automatic reinforcer. Attempts to engage in the target behavior were blocked by placing the experimenter's hand between the participant's hand and the materials involved in arranging and ordering and completeness. If the experimenter could not block the response, the target behavior was interrupted and the item ordered or completed was immediately replaced in its original position.

Matched items plus prompts plus response blocking 2 s

Jim engaged in successive attempts to arrange and order or to complete materials during matched items plus prompts plus response-blocking sessions. In an effort to interrupt repeated attempts at the target behavior more effectively, the response-blocking component was modified in this condition such that the experimenter guided Jim's hands to his lap for 2 s.

Teacher implementation

To identify whether the effects of the final intervention package would be maintained when implemented by Jim's teachers, two of his teachers (Teachers A and B) implemented the final treatment. All other stimulus conditions remained constant. Prior to each teacher's first session, the experimenter demonstrated the procedures and answered questions. Subsequent sessions were preceded by a brief review of the procedures and an opportunity for teachers to ask questions. Immediate corrective feedback was provided during sessions as necessary.

Ross

Although Ross's escape analysis suggested that response blocking was sufficient for decreasing his target behavior, we conducted a separate treatment evaluation to determine (a) the influence of competing items on target behavior and item engagement and (b) whether the effects of response blocking would persist under less than optimal procedural integrity.

Baseline

Baseline was similar to the no-interaction condition of the functional analysis.

Matched items

Sessions were similar to baseline except that two matched items were available continuously. Matched items were selected based on results of a separate competing items assessment (see Piazza et al., 2000). Stimuli associated with high levels of item engagement and low levels of target behavior included a Lite Brite, basketball pinball, and maze.

Matched items plus intermittent response blocking

Because levels of responding did not recover when response blocking was removed in the return to no-interaction and escape conditions in the escape analysis (Figure 2, top), we hypothesized that responding would be maintained at low levels even when response blocking was implemented intermittently. If effective, intermittent response blocking would serve as a practical alternative to blocking every response, particularly because Ross typically had a 1∶2 teacher-to-student ratio. Sessions were identical to the matched items condition except that the experimenter blocked the first three of every four attempts to engage in a target behavior (e.g., see Lerman & Iwata, 1996b; Smith, Russo, & Le, 1999). Because data on arranging and ordering were collected via a duration measure, we developed criteria for initiating response blocking during (or following) the fourth attempt, during which Ross was allowed to arrange and order. The three-of-four sequence of response blocking was reinitiated following (a) 10 s of arranging and ordering, (b) a 3-s pause between instances of a target behavior (criterion for turning off the duration key during data collection for arranging and ordering was 3 s), or (c) an attempt to arrange and order, complete, or wash and clean a new item.

Teacher implementation

This condition was the same as Jim's teacher implementation condition.

Christie

Christie's process versus product analysis identified the product of arranging and ordering as the reinforcer. Because her preferred furniture placement was neither practical nor stable, an antecedent approach in which furniture remained according to her preferred product was not a viable treatment option. Thus, we conducted a separate treatment evaluation to explore other options.

Baseline

Baseline was identical to the no-interaction condition of the functional analysis.

Matched items

Sessions were similar to baseline except that matched items were available continuously. In an attempt to provide materials that could be arranged and ordered but on a smaller, more contained scale, we began by including a diorama of a living room with miniature dollhouse furniture. However, because the dollhouse furniture did not appear to compete with arranging and ordering, we added three matched items (Session 12) based on results of a single-stimulus engagement preference assessment (e.g., DeLeon, Iwata, Conners, & Wallace, 1999). A circus set, garden stringing beads, Beauty and the Beast magnet board, and dollhouse furniture were associated with the highest levels of item engagement during the assessment.

Matched items plus prompts

This condition was similar to the matched items condition except that nondirective vocal and model prompts (e.g., Piazza, Contrucci, Hanley, & Fisher, 1997) to engage with matched items were provided every 30 s. Specifically, the experimenter modeled appropriate item engagement while describing her actions (e.g., “I'm setting up the couches in front of the TV like a movie theater” while manipulating the dollhouse furniture) or following a predetermined play script (e.g., “First up we have Pablo on the trapeze!” while placing the circus character on the trapeze).

Matched items plus prompts plus product extinction

This condition was similar to the matched items plus prompts condition except that the automatic reinforcer associated with arranging and ordering furniture was eliminated (i.e., extinction). Based on the results of the process versus product analysis, extinction involved immediately replacing furniture in its original arrangement contingent on arranging and ordering (hereafter referred to as product extinction). On one occasion (Session 36), Christie moved the TV cabinet and then wedged herself between the cabinet and the wall such that the experimenter was not able to replace the cabinet to its original position. In this situation, the experimenter prevented Christie from moving the cabinet any further by placing herself on the other side of the cabinet and moving the cabinet to its original location after Christie moved from behind it, which occurred at the end of session. As a more conservative measure of the effects of product extinction, the time during which Christie physically prevented the experimenter from replacing the cabinet was scored as arranging and ordering.

Matched items plus prompts plus product extinction plus reinforcement for engagement

Although arranging and ordering had decreased to desirable levels, item engagement remained low. Thus, we conducted separate training sessions to teach Christie appropriate item engagement (data available from the first author). Procedures used during play skills training were then added to the treatment evaluation to determine their effect on item engagement and arranging and ordering. Specifically, nondirective vocal and model prompts were provided (a) at the start of session, (b) every 30 s without item engagement, and (c) immediately after termination of the reinforcement period. Contingent on 120 s of cumulative item engagement, Christie was given 120 s of access to a video that contained a collection of preferred movie scenes. This reinforcer was selected based on teachers' reports that Christie typically watched videos during her free time and repeatedly requested to watch particular movie scenes in succession. An audible timer was used to track her cumulative item engagement.

Teacher implementation

This condition was the same as Jim's teacher implementation condition except that the final intervention package was implemented by three of Christie's teachers (Teachers A, B, and C).

Results and Discussion

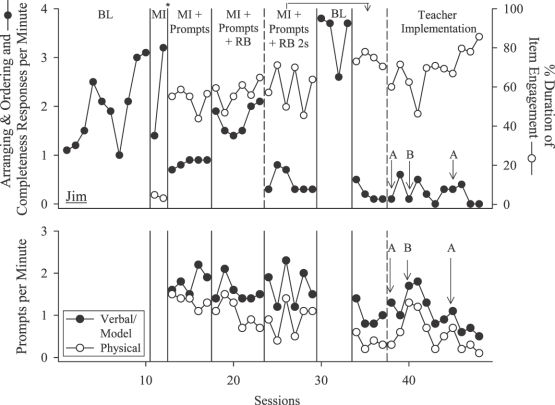

Jim

Figure 4 (top) shows the results of Jim's treatment evaluation. We began with an assessment of the effects of providing access to matched items amenable to appropriate forms of arranging and ordering and completeness. High rates of compulsive-like behavior and low levels of item engagement suggested that the automatic reinforcement produced by engaging with matched items did not compete with the automatic reinforcement produced by engaging in arranging and ordering and completeness. Next, we conducted separate training sessions to bring his behavior into contact with the putative automatic reinforcement produced by engaging with matched items by teaching him how to engage with leisure items appropriately. When prompts were introduced into the treatment evaluation (matched items plus prompts), the level and variability of arranging and ordering and completeness decreased and item engagement increased. Because the rate of prompting during this condition remained high, it seems unlikely that the effects of prompts can be attributed to increased contact with the putative automatic reinforcement produced by engaging with matched items. Instead, prompts may have served to interrupt compulsive-like behavior, perhaps by diverting attention, albeit temporarily, away from the materials that he typically arranged and ordered or completed.

Figure 4.

The top panel shows combined arranging and ordering and completeness responses per minute (filled circles, primary y axis) and the percentage duration of item engagement (open circle, secondary y axis) during Jim's treatment evaluation. BL = baseline, MI = matched items, RB = response blocking; the asterisk indicates the point at which separate play skills training sessions were conducted (between Sessions 12 and 13). Letters in the teacher implementation phase represent sessions conducted by different teachers (Teacher A and Teacher B). The bottom panel shows the rate of vocal and model (filled circles) and physical (open circles) prompts.

To further decrease the rate of compulsive-like behavior, we introduced response blocking, but the rate of arranging and ordering and completeness increased. When the length of response blocking was extended to 2 s, rates of compulsive-like behavior decreased below those observed in the matched items plus prompts condition. Extending the duration of response blocking appeared to interrupt his successive attempts to arrange and order or complete an item. The effects of the final intervention package were maintained when the package was implemented by Jim's teachers.

In the final sessions of the teacher implementation condition (Sessions 45 through 48), the rate of prompting was on a decreasing trend (bottom panel), and the percentage of item engagement was on an increasing trend (top panel). It is possible that, with repeated exposure, engaging with matched items may have begun to take on automatic reinforcement properties. High levels of item engagement in the absence of prompting would provide further evidence of this possibility. Alternatively, it is possible that item engagement served to avoid prompts (prompts were delivered every 15 s unless Jim was already engaged with matched items) and that increases in item engagement can be attributed to negative social reinforcement. Additional analyses would be necessary to evaluate the behavioral processes that were responsible for increased item engagement.

Ross

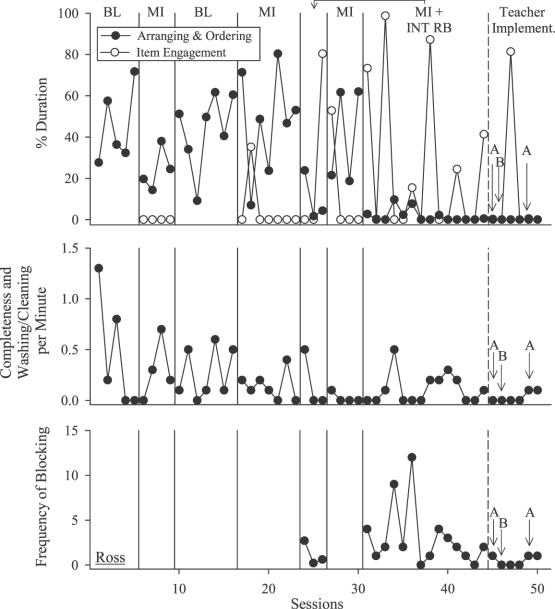

Figure 5 (top) shows the results of Ross's treatment evaluation. Levels of arranging and ordering decreased when matched items first were introduced; however, these effects were not replicated when matched items were reintroduced following a reversal to baseline, suggesting that the availability of matched items alone did not influence target responding. Further, with the exception of two sessions, Ross did not engage with matched items during the matched items condition. Despite the fact that matched items did not influence target behavior, they continued to be made available during the remainder of the treatment evaluation to provide Ross with an appropriate alternate activity during sessions. The second matched items condition also served as a baseline from which to evaluate the effects of matched items plus intermittent response blocking, during which levels of arranging and ordering decreased and rates of completeness and washing and cleaning remained low. Functional control over the effects of intermittent response blocking was demonstrated with arranging and ordering, and the effects of this treatment persisted when implemented by Ross's teachers. Perhaps most notable is that the frequency of response blocking decreased and was maintained at low levels by the end of the treatment evaluation. Collectively, these results suggest that the effects of response blocking will persist even when implemented with less than optimal procedural integrity. It also should be noted that, although minor self-injury, property destruction, and tantrums were reported to be associated with interruption of compulsive-like behavior, this behavior was not observed during the assessment or treatment of Ross's compulsive-like behavior in this study.

Figure 5.

The percentage duration of arranging and ordering and item engagement (top panel; filled circles and open circles, respectively), completeness, and washing and cleaning responses per minute (middle panel), and frequency of the experimenter blocking target responses (bottom panel) during Ross's treatment evaluation. BL = baseline, MI = matched items, INT RB = intermittent response blocking. Letters in the teacher implementation phase of the treatment evaluation represent sessions conducted by different teachers (Teacher A and Teacher B).

Lerman and Iwata (1996b) suggested that the processes (extinction vs. punishment) that are responsible for decreased responding can be determined by manipulating the schedule of consequences. If extinction is responsible for decreased responding when response blocking is implemented on a continuous schedule, behavior maintained by automatic reinforcement would be expected to increase when response blocking is implemented intermittently. In other words, responding presumably would contact reinforcement on an intermittent schedule. By contrast, responding would be expected to remain low if punishment is in effect. This logic, however, presumes that each instance of behavior contacts automatic reinforcement. If Ross's arranging and ordering, completeness, or washing and cleaning were reinforced, for example, by an orderly environment, then the orderly environment may have not been contacted even when responding was not blocked. For example, Ross often arranged the dates that were attached to the calendar via Velcro such that they were aligned and in order. If the reinforcer was to obtain an orderly calendar, then aligning or ordering only several of the dates of the calendar may have not been sufficient to bring his behavior in contact with reinforcement. In other words, extinction may have been in effect even when response blocking was intermittent. Thus, the processes that were responsible for the effects of response blocking remain unknown.

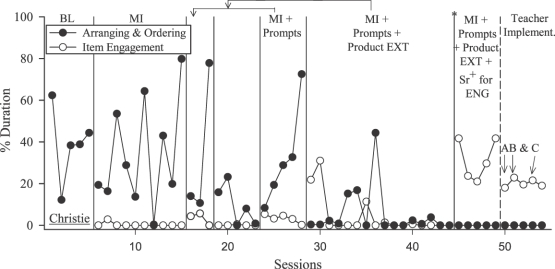

Christie

Figure 6 (top) shows the results of Christie's treatment evaluation. Levels of arranging and ordering were variable in the initial baseline, with the last three data points ranging from 38% to 44%. The addition of matched items (matched items condition) and prompts (matched items plus prompts) did not influence levels of arranging and ordering. By contrast, levels of arranging and ordering decreased and were maintained at low levels in the matched items plus prompts plus product extinction condition. The introduction of supplemental reinforcement for engaging with matched items increased levels of item engagement, and the effects of the final intervention package were maintained when the treatment was implemented by Christie's teachers.

Figure 6.

The top panel shows the percentage duration of arranging and ordering of furniture and the percentage duration of item engagement during Christie's treatment evaluation. BL = baseline, MI = matched items, EXT = extinction, Sr+ for ENG = reinforcement contingent on item engagement; the asterisk indicates the point at which separate play skills training was conducted (between Sessions 44 and 45). Letters in the teacher implementation phase represent sessions conducted by different teachers (Teachers A, B, and C).

Overall, Christie's results suggested that product extinction was necessary for maintaining low levels of arranging and ordering. Although prompts and reinforcement (i.e., access to preferred video scenes) also were provided during her final intervention package to maintain item engagement, it seems unlikely that matched items had taken on automatically reinforcing properties. Although response blocking should serve to disrupt the response–reinforcer relation regardless of whether the automatic reinforcer is the process or product of arranging and ordering, the ability to program an alternate form of extinction (furniture replacement) was particularly desirable because teachers had hesitated to implement procedures that required physical contact. Procedural integrity for response blocking ultimately may have been compromised if Christie's aggression or self-injury functioned as a punisher for teachers' physical contact.

Because interruption of arranging and ordering was reported to be associated with aggression, we collected data on this behavior during all experimental analyses (no differential consequences were provided for nontarget behavior). With few exceptions, each change of condition in the treatment evaluation was associated with an initial increase in aggression followed by decreased levels of responding. Aggression was maintained at zero levels during implementation of the final treatment in the second to last phase and when the final treatment was implemented by Christie's teachers. We did not observe any self-injury throughout Christie's treatment evaluation.

Several general limitations of the treatment evaluations should be noted. First, the effect of the final treatment was not evaluated across all relevant settings in the participants' natural environment. Jim's treatment evaluation was conducted in an analogue setting, and although the treatment evaluation was conducted in settings frequently encountered by Ross (a recreational room in his residence) and Christie (the living room of her residence where arranging and ordering was reported to be most problematic), compulsive-like behavior also was reported to occur in other settings at their residence (e.g., kitchen) and school. Second, it would have been relevant to determine whether Jim's final treatment reduced compulsive-like behavior during instructional contexts, given that these contexts were reported to be problematic and levels of compulsive-like behavior were relatively high during the escape condition of his functional analysis. Finally, the final treatment was relatively labor intensive, particularly in the components for increasing item engagement for Jim and Christie. Further research would be necessary to determine whether procedures applied in the final treatment would produce durable behavior change across all relevant contexts in the participants' natural environment and to what extent the intensity of behavioral support could be reduced over time.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Research suggests that extinction may be integral to ensuring treatment success (e.g., Iwata, Pace, Cowdery, & Miltenberger, 1994). In our study, treatment components aimed at disrupting the response–reinforcer relation (response blocking or product extinction) were necessary to obtain desirable treatment outcomes for all participants. Simply providing access to stimuli that were amenable to appropriate forms of compulsive-like behavior (matched items) did not reduce the target behavior for any of the participants. Further, prompting or prompting plus supplemental reinforcement was necessary to maintain engagement with matched items for Jim and Christie, suggesting that these items did not function as reinforcers.

Although response blocking or product extinction was sufficient to reduce compulsive-like behavior to desirable levels, it often is considered best practice to provide an alternate means of accessing the functional reinforcer, for example, by programming its availability via differential reinforcement of alternative behavior, differential reinforcement of other behavior, or noncontingent reinforcement (Lerman & Iwata, 1996a; Van Houten et al., 1988). In addition to providing the individual with the opportunity to access personally relevant reinforcers, these procedures may enhance the effects of treatment by addressing the motivating operation. Because matched items did not appear to compete with compulsive-like behavior in our study, it seems unlikely that the motivating operation was addressed. Other procedures designed to address the motivating operation, such as providing an opportunity to engage in compulsive-like behavior following a functional communication response, were not appropriate for these participants, given that the compulsive-like behavior itself was undesirable (particularly forms that were considered dangerous such as arranging furniture or trash). Future research might explore acceptable methods of addressing the motivating operation when automatically reinforced behavior is undesirable (e.g., by allowing appropriate forms of compulsive-like behavior).

We did not conduct a process versus product analysis for Jim and Ross, in part because consistencies in the arrangement of items could not be identified easily for all topographies, but also because response blocking prevents access to a final product placement. Further, aggression or self-injury was not reported to be associated with physical contact for Jim or Ross, and response blocking already had been shown to be effective for Ross during his escape analysis. One potential advantage of conducting a process versus product analysis, even when response blocking is likely to be effective, is that the caregiver has slightly more time to respond to the target behavior when implementing product extinction. If the compulsive-like behavior is maintained by access to a product, any potential detrimental effects of procedural integrity errors with response blocking may be mitigated by immediately replacing the items in their original positions. Future research may explore this possibility; a parametric analysis of various durations of delays to the replacement of items also may be useful for identifying the effects of different types of procedural integrity errors and increasing the practicality of treatment.

The procedures used to identify whether the final placement of items functioned as a reinforcer for Christie's arranging and ordering required that the putative preferred product be identified prior to conducting the process versus product analysis. Such antecedent conditions may be difficult to arrange if consistencies in the final placement of items cannot be identified (e.g., there was no apparent pattern to Ross's arranging of trash in trash bins), or the establishing operation for the product as a reinforcer is subtle or difficult to control (e.g., Jim might dart across the room to close a drawer that was only slightly ajar). As noted by Ross's teacher during an interview, it would be difficult to avoid or prevent compulsive-like behavior altogether; “[teachers] couldn't possibly control everything. … There is always going to be something on the floor somewhere or something like a book on a shelf that is not facing the correct way.” An alternative means of identifying whether the final placement of items functions as a reinforcer would be to assess the effects of product extinction. In other words, as is suggested by the results of Ross's escape analysis and several other studies that have used similar procedures (e.g., Kuhn et al., 1999; Smith, Iwata, Vollmer, & Zarcone, 1993; Thompson, Fisher, Piazza, & Kuhn, 1998), function-based treatments can be used to clarify functional relations. Should arranging and ordering persist when items are replaced immediately in their original position contingent on arranging and ordering, then the process of arranging and ordering rather than the final placement of items is likely to be the variable that maintains this behavior.

We have stressed the role of functional analyses in developing treatments, but results from functional analyses also contribute to our understanding of common maintaining variables. In their review of the literature on assessment and treatment of stereotypy, Rapp and Vollmer (2005) noted that the overwhelming majority of the literature suggests that most stereotypy is maintained by automatic reinforcement. It is possible that, like lower level restricted and repetitive behavior, higher level restricted and repetitive behavior is maintained most commonly by automatic reinforcement. Additional research is needed to determine the extent to which higher level restricted and repetitive behavior in autism is susceptible to social contingencies.

Arranging and ordering, completeness, and washing and cleaning in children with autism are commonly described as compulsive behavior (e.g., Bodfish et al., 1999), perhaps because they share topographical similarities with the behavior of individuals with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). However, it is unknown whether the compulsive-like behavior of individuals with autism also shares functional similarities with the compulsive behavior of individuals with OCD, which is presumed to be maintained by automatic negative reinforcement (i.e., avoidance of aversive stimuli; Maltby & Tolin, 2003). It is interesting to note that exposure plus response prevention, which is commonly used to treat compulsions in OCD, also shares topographical and functional similarities with the treatment components found to be effective in the present study (e.g., response blocking). If problem behavior is maintained by automatic negative reinforcement, then planned and therapist-controlled exposure to aversive stimuli (e.g., graduated exposure) may enhance the effects of treatment (Abramowitz, 1996). Future research might evaluate whether the conditions under which compulsive-like behavior occurs are aversive for individuals with autism (e.g., via a concurrent-chains arrangement; see Hanley, Piazza, Fisher, Contrucci, & Maglieri, 1997). Other potential sources of automatic reinforcement, such as “sameness” (e.g., Prior & MacMillan, 1973), might also be explored.

Although several hypotheses as to the function of higher level restricted and repetitive behavior have been proposed (e.g., see brief review by Flannery & Horner, 1994), we believe that the present study represents the first attempt to identify the function of higher level restricted and repetitive behavior in autism using experimental analyses. Results from our study suggest that functional analysis methodology, which has been used to assess and treat lower level restricted and repetitive behavior, may be useful for assessing and treating higher level restricted and repetitive behavior. Arranging and ordering and other compulsive-like behaviors were amenable to common function-based treatment components for all three participants. Experimental analyses similar to those used in this study may inform treatment of problematic forms of arranging and ordering or other compulsive-like behavior.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted in partial fulfillment of the first author's requirements for the doctoral degree at Western New England College. We thank Gregory P. Hanley, Amanda M. Karsten, and William H. Ahearn for their thoughtful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

The terms compulsive-like behavior or compulsive behavior will be used to refer to responses that share topographical similarities with the behavior of individuals with obsessive compulsive disorder and for the purpose of maintaining consistency with the terminology used in the RBS-R scale (Bodfish, Symons, & Lewis, 1999). In particular, compulsive-like behavior will be used when referring to any of the responses included in the compulsive behavior subscale of the RBS-R scale (e.g., arranging and ordering, completeness, or washing and cleaning).

See Response Measurement and Interobserver Agreement section for operational definition of completeness. The terms completeness or complete items will be used to refer to responses outlined in this operational definition.

REFERENCES

- Abramowitz J.S. Variants of exposure and response prevention in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis. Behavior Therapy. 1996;27:583–600. [Google Scholar]

- Bodfish J.W. Treating the core features of autism: Are we there yet. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities. 2004;10:318–326. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodfish J.W, Symons F.W, Lewis M.H. The Repetitive Behavior Scale. Western Carolina Center Research Reports. 1999.

- Bodfish J.W, Symons F.J, Parker D.E, Lewis M.H. Varieties of repetitive behavior in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities. 2000;30:237–243. doi: 10.1023/a:1005596502855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners J, Iwata B.A, Kahng S, Hanley G.P, Worsdell A.S, Thompson R.H. Differential responding in the presence and absence of discriminative stimuli during multielement functional analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33:299–308. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuccaro M.L, Shao Y, Grubber J, Slifer M, Wolpert C.M, Donnelly S.L, et al. Factor analysis of restricted and repetitive behaviors in autism using the autism diagnostic interview–Revised. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2003;34:3–17. doi: 10.1023/a:1025321707947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon I.G, Iwata B.A, Conners J, Wallace M.D. Examination of ambiguous stimulus preferences with duration-based measures. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32:111–114. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap G, Dyer K, Koegel R.L. Autistic self-stimulation and intertrial interval duration. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 1983;88:194–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Lindauer S.E, Alterson C.J, Thompson R.H. Assessment and treatment of destructive behavior maintained by stereotypic object manipulation. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:513–527. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza C.C, Bowman L.G, Hagopian L.P, Owens J.C, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W.W, Piazza C, Cataldo M, Harrell R, Jefferson G, Conner R. Functional communication training with and without extinction and punishment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:23–36. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery K.B, Horner R.H. The relationship between predictability and problem behavior for students with severe disabilities. Journal of Behavioral Education. 1994;4:157–176. [Google Scholar]

- Green V.A, Sigafoos J, Pituch K.A, Itchon J, O'Reilly M.O, Lancioni G.E. Assessing behavioral flexibility in individuals with developmental disabilities. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2006;21:230–236. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley G.P, Iwata B.A, McCord B.E. Functional analysis of problem behavior: A review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:147–185. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley G.P, Piazza C.C, Fisher W.W, Contrucci S.A, Maglieri K.A. Evaluation of client preference for function-based treatment packages. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:459–473. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausman N, Kahng S, Farrell E, Mongeon C. Idiosyncratic functions: Severe problem behavior maintained by access to ritualistic behaviors. Education and Treatment of Children. 2009;32:77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B.A, Dorsey M.F, Slifer K.J, Bauman K.E, Richman G.S. Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:197–209. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197. (Reprinted from Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 2, 3–20, 1982) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B.A, Pace G.M, Cowdery G.E, Miltenberger R.G. What makes extinction work: An analysis of procedural form and function. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:131–144. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B.A, Pace G.M, Dorsey M.F, Zarcone J.R, Vollmer T.R, Smith R.G, et al. The functions of self-injurious behavior: An experimental-epidemiological analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:215–240. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R.S.P, Wint D, Ellis N.C. The social effects of stereotyped behavior. Journal of Mental Deficiency Research. 1990;34:261–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1990.tb01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child. 1943;2:217–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy C.H, Meyer K.A, Knowles T, Shukla S. Analyzing the multiple functions of stereotypical behavior for students with autism: Implications for assessment and treatment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33:559–571. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn D.E, DeLeon I.G, Fisher W.W, Wilke A.E. Clarifying an ambiguous functional analysis with matched and mismatched extinction procedures. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32:99–102. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn D.E, Hardesty S.L, Sweeney N.M. Assessment and treatment of excessive straightening and destructive behavior in an adolescent diagnosed with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:355–360. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman D.C, Iwata B.A. Developing a technology for the use of operant extinction in clinical settings: An examination of basic and applied research. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996a;29:345–382. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman D.C, Iwata B.A. A methodology for distinguishing between extinction and punishment effects associated with response blocking. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996b;29:231–233. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltby N, Tolin D.F. Overview of treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder and spectrum conditions: Conceptualization, theory, and practice. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 2003;3:127–144. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy G, Macdonald S, Hall S, Oliver C. Aggression and the termination of “rituals”: A new variant of the escape function for challenging behavior. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2000;21:43–59. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(99)00029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza C.C, Adelinis J.D, Hanley G.P, Goh H, Delia M.D. An evaluation of the effects of matched stimuli on behaviors maintained by automatic reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33:13–27. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza C.C, Contrucci S.A, Hanley G.P, Fisher W.W. Nondirective prompting and noncontingent reinforcement in the treatment of destructive behavior during hygiene routines. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:705–708. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza C.C, Fisher W.W, Hanley G.P, LeBlanc L.A, Worsdell A.S, Lindauer S.E, et al. Treatment of pica through multiple analyses of its reinforcing functions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:165–189. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior M, MacMillan M.B. Maintenance of sameness in children with Kanner's syndrome. Journal of Autism and Childhood Schizophrenia. 1973;3:154–167. doi: 10.1007/BF01537990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp J.T, Vollmer T.R. Stereotypy I: A review of behavioral assessment and treatment. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2005;26:527–547. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R.G, Iwata B.A, Vollmer T.R, Zarcone J.R. Experimental analysis and treatment of multiply controlled self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:183–196. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R.G, Russo L, Le D.D. Distinguishing between extinction and punishment effects of response blocking: A replication. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32:367–370. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South M, Ozonoff S, McMahon W.M. Repetitive behavior profiles in Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005;35:145–158. doi: 10.1007/s10803-004-1992-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R.H, Fisher W.W, Piazza C.C, Kuhn D.E. The evaluation and treatment of aggression maintained by attention and automatic reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:103–116. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner M. Repetitive behaviour in autism: A review of psychological research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:839–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houten R, Axelrod S, Bailey J.S, Favell J.E, Foxx R.N, Iwata B.A, et al. The right to effective behavioral treatment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1988;21:381–384. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1988.21-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer T.R, Marcus B.A, LeBlanc L. Treatment of self-injury and hand mouthing following inconclusive functional analyses. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:331–344. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]