Abstract

Past research has shown that response interruption and redirection (RIRD) can effectively decrease automatically reinforced motor behavior (Hagopian & Adelinis, 2001). Ahearn, Clark, MacDonald, and Chung (2007) found that a procedural adaptation of RIRD reduced vocal stereotypy and increased appropriate vocalizations for some children, although appropriate vocalizations were not targeted directly. The purpose of the current study was to examine the effects of directly targeting appropriate language (i.e., verbal operant training) on vocal stereotypy and appropriate speech in 3 children with an autism spectrum disorder. The effects of verbal operant (i.e., tact) training were evaluated in a nonconcurrent multiple baseline design across participants. In addition, RIRD was implemented with 2 of the 3 participants to further decrease levels of vocal stereotypy. Verbal operant training alone produced slightly lower levels of stereotypy and increased appropriate vocalizations for all 3 participants; however, RIRD was required to produce acceptably low levels of stereotypy for 2 of the 3 participants.

Keywords: autism, response blocking, response interruption, tact, verbal behavior, vocal stereotypy

Echolalia is among the key criteria for diagnosing individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD; Lewis & Bodfish, 1998). Two forms of echolalia, immediate and delayed, have been described in the literature. Immediate echolalia is defined as repeating the speech of others directly after they speak, whereas delayed echolalia entails repeating words, sounds, or phrases that are inappropriate to the current context (Ahearn, Clark, MacDonald, & Chung, 2007; Schreibman & Carr, 1978). In many cases, the utterances are not clearly articulated repetitions and take the form of babbling, squealing, or grunting repetitively. Ahearn et al. (2007) referred to all of these types of vocalizations as vocal stereotypy.

Young children with ASD are often more likely to emit repetitive noises or noncontextual words than they are to communicate appropriately and effectively. Engaging in this form of stereotypy presents several potentially adverse effects for these individuals. Stereotypy interferes with positive social interactions, skill acquisition, and appropriate play skills (Dunlap, Dyer, & Koegel, 1983). Furthermore, such behavior can be stigmatizing in community settings (Jones, Wint, & Ellis, 1990; MacDonald et al., 2006; Schreibman & Carr, 1978; E. A. Smith & Van Houten, 1996). Thus, reducing vocal stereotypy and developing functional verbal behavior in children with ASD are important clinical goals.

Although some research on stereotypy has indicated mediation by social consequences, functional analyses of vocal stereotypy frequently have demonstrated maintenance by sensory consequences (Ahearn et al., 2007; Taylor, Hoch, & Weisman, 2005). Self-stimulatory behavior belongs to a class of operant responses that presumably are reinforced by perceptual or sensory stimuli automatically produced by engaging in the response (Lovaas, Newsom, & Hickman, 1987). Nonsocial reinforcement contingencies present a challenge for treatment because the reinforcing consequences are not accessible to others (Vollmer, 1994) and cannot be readily manipulated during intervention.

Many researchers have used the interruption of self-stimulatory behavior, or response blocking, to effectively decrease automatically reinforced problem behavior (Fellner, LaRoche, & Sulzer-Azaroff, 1984; Hagopian & Adelinis, 2001; Lerman & Iwata, 1996; Rincover, 1978; R. G. Smith, Russo, & Le, 1999). Unfortunately, response blocking alone may cause side effects such as aggression. Hagopian and Adelinis (2001) found that redirection was a necessary accompaniment to response blocking for motor stereotypy to reduce side effects and increase appropriate forms of behavior. Ahearn et al. (2007) developed a practical procedure to overcome the challenges involved in physically blocking vocalizations and termed the procedure response interruption and redirection (RIRD). Following functional assessment indicating that vocal stereotypy was automatically reinforced, the authors evaluated the effects of RIRD using a withdrawal design. Contingent on stereotypy, the therapist prompted the child to emit appropriate language that was already in his or her repertoire (e.g., vocal imitation, answers to social questions). These prompts were delivered following each instance of stereotypy until the participant complied with three consecutive demands in the absence of stereotypy. All four participants experienced a decrease in vocal stereotypy, and untrained appropriate vocalizations increased for three of the four participants as an additional but untargeted effect of treatment.

Other studies also have illustrated that skill-acquisition procedures not only directly increase appropriate behavior but also may decrease inappropriate behavior. For example, the cues-pause-point procedure developed by McMorrow and Foxx (1986) has been used to replace inappropriate vocalizations (i.e., immediate echolalia) with appropriate vocalizations (i.e., to say “fine” when asked “How are you?”). Specific instruction (e.g., verbal operant training) may compete effectively with vocal stereotypy while simultaneously increasing the individual's verbal repertoire and promoting functional language in the place of stereotypy. Verbal operant training is based on the framework established by Skinner (1957), and defines verbal operants according to their controlling antecedent and consequent events. For example, Skinner defined the tact as a verbal operant that is evoked by a nonverbal stimulus, such as an object or an event, and is maintained by nonspecific reinforcement such as a generalized or social reinforcer. In comparison, mands refer to a verbal operant maintained by specific consequences related to a motivational operation (Laraway, Snycerski, Michael, & Poling, 2003), such as deprivation or aversive stimulation (Michael, 1988). These two verbal operants, along with the echoic (i.e., exact reproduction of a vocal stimulus) are the primary targets in early language training for children with ASD (Sundberg & Michael, 2001).

The current study extended the research conducted by Ahearn et al. (2007) by examining the effects of specific verbal operant training on appropriate vocalizations and vocal stereotypy with children diagnosed with ASD. The purpose of this study was to determine whether stereotypy would decrease as appropriate vocalizations increased during language training without using RIRD. All participants emitted mands reliably; therefore, tacts offered the most suitable verbal operant to be trained.

METHOD

Participants and Setting

One girl and two boys served as participants. Each had been diagnosed with an ASD and exhibited vocal stereotypy at levels that interfered with their academic activities or occurred at unacceptable levels outside of their school classroom. For all participants, individual education plan goal summaries and teacher report were used to assess their verbal repertoires. No standardized assessments of the verbal operants were employed. Anna was an 8-year-old girl who emitted spontaneous mands in the form of one-word utterances such as “bathroom” and “candy.” No tacts were evident in her verbal repertoire. Jeff was a 10-year-old boy who frequently displayed spontaneous mands throughout the day in the form of full sentences; however, he did not participate in conversational exchanges and did not consistently tact stimuli. Both Anna and Jeff attended a day-school program that specialized in the education and treatment of children with ASD. Parker was a 10-year-old boy who attended a full-time residential school program and communicated vocally. He spoke in full sentences and emitted spontaneous mands; however, he did not participate in conversational exchanges or emit spontaneous tacts.

All sessions were conducted in an experimental room (1.5 m by 3 m) equipped with a wide-angle video camera, microphone, a table and two chairs, and materials necessary to conduct sessions. During the functional analysis, materials included moderately preferred leisure items or demand-related items. During baseline and treatment sessions, materials included a trifold board (92 cm by 122 cm) that displayed photos (7.6 cm by 7.6 cm) of 23 common stimuli that included everyday items for participants to comment on (e.g., chair, flower, book, house, pencil, car, markers, etc.) and 11 high- and moderate-preference stimuli, a bin with all preferred stimuli depicted on the board (both edible and leisure items), a session timer, and relevant data sheets. The experimenter was present during each session except the alone condition of the functional analysis (only the participant was in the room).

Design

A multielement design was used during the functional analysis. A nonconcurrent multiple baseline design across participants was used to analyze the effects of verbal operant training on appropriate vocalizations and vocal stereotypy. If necessary, RIRD was implemented and examined using a reversal design for each participant exposed to this procedure.

Response Measurement and Interobserver Agreement

During the functional analysis, vocal stereotypy was defined as any instance of noncontextual or nonfunctional vocalizations, including repetitive babbling, grunts, squeals, and phrases unrelated to the present situation. Examples included vocalizations such as “ee bah ee” and “ahhhhhhh” outside the context of a vocal imitation task and laughter in the absence of a humorous external event. Nonexamples included functional speech to request an item (e.g., “I want cookies”) or making sounds in compliance with vocal imitation tasks prompted by the experimenter. Data on the occurrence of vocal stereotypy were scored using a 10-s momentary time-sampling procedure in which a 2-s observation occurred during every 10 s of session time. Momentary time sampling was chosen over partial-interval recording based on the results of Gardenier, MacDonald, and Green (2004), who found that partial-interval recording overestimated the duration of stereotypy compared to momentary time sampling. A second observer scored videotaped samples from each session, and interobserver agreement was calculated by dividing the number of intervals with agreements by the total number of intervals with agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100%. A second observer scored a minimum of 33% of sessions in each condition for each participant. Mean total agreement for vocal stereotypy was 99% (range, 93% to 100%) for Anna, 100% for Jeff, and 92% (range, 87% to 97%) for Parker.

The definition of vocal stereotypy remained the same during the intervention analysis. In addition, appropriate vocalizations were defined as any functional or contextually appropriate vocalization and were divided into three subcategories: framed tacts, framed mands, and unspecified language. Framed tacts were defined as the use of an autoclitic frame (e.g., “I see” or “it's a”) paired with an appropriate object label. Examples included “I see book” and “It's a toy” in the presence of contextually relevant stimuli. Nonexamples included labels such as “car” or stating “I see dog” in the absence of contextually relevant stimuli. Framed mands were defined as the use of an autoclitic frame (e.g., “I want” or “give me”) paired with an appropriate object label. Examples included stating “I want candy” or “Give me toy.” Nonexamples included labels (e.g., “candy” or “book”). Unspecified language was defined as the use of an appropriate label in the presence of contextually relevant stimuli with an unclear function due to the lack of an autoclitic frame and multiple potential controlling stimuli (e.g., “apple” in the presence of an apple that was also a preferred stimulus). Nonexamples included framed tacts or mands, noncontextual words, sounds (e.g., “ee bah ee,” “ahhh”) or phrases. Unspecified language may have functioned as a mand or a tact for the speaker; however, without an autoclitic frame it was difficult for the listener to determine the function.

During the treatment evaluation, a second-by-second continuous duration data-collection procedure was used to measure vocal stereotypy, which is reported as the proportion of the session containing stereotypy (i.e., total duration with stereotypy divided by total session duration). Data were collected on the frequency of appropriate vocalizations. A second observer scored video footage from 33% of all sessions for each phase for each participant. An agreement was scored if both observers recorded exactly the same duration and time of occurrence of vocal stereotypy duration or exactly the same total frequency of appropriate vocalizations in a session. Agreements were divided by agreements plus disagreements and multiplied by 100%. Mean agreement was 95% (range, 87% to 97%) for vocal stereotypy and 97% (range, 89% to 100%) for appropriate vocalizations for Anna, 96% (range, 93% to 100%) for vocal stereotypy and 97% (range, 90% to 100%) for appropriate vocalizations for Jeff, and 94% (range, 78% to 99%) for vocal stereotypy and 96% (range, 90% to100%) for appropriate vocalizations for Parker.

Procedure

Preference assessments

Paired-stimulus preference assessments were conducted to identify individually preferred leisure and edible items for use during the functional analysis and treatment sessions. The leisure item and edible item preference assessments were conducted separately. Eight stimuli were used in each assessment (similar to Fisher et al., 1992). The order of presentation was randomized, and each item was presented a total of 14 times across 56 trials. During each trial, the participant gained access to the item approached for 30 s, and the second item was removed. High-preference items were those selected by the participant in at least 80% of opportunities. Moderate-preference items were those selected by the participant in 50% to 80% of opportunities, and low-preference items were those selected in fewer than 50% of opportunities. Based on the results of each individual preference assessment, 11 items of high to moderate preference were selected for mand training. These items were present in all sessions.

Functional analysis

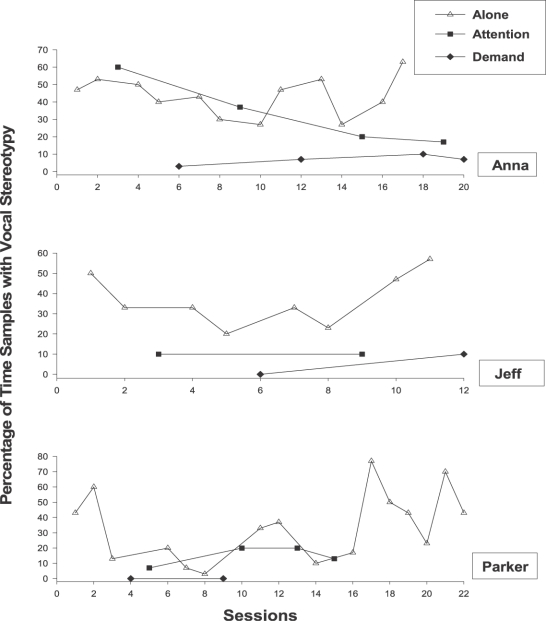

A brief functional analysis of vocal stereotypy was conducted using a subset of the conditions described by Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, and Richman (1982/1994) alternated in a multielement design (see Figure 1). Sessions were 5 min in duration, and the conditions were alternated quasirandomly. As in Roscoe, Carreau, MacDonald, and Pence (2008), stereotypy was suspected to be automatically reinforced. Therefore, the play condition was omitted and a series of alone conditions were conducted with periodic probes of the demand and attention conditions to better determine whether the maintaining variable of stereotypy for each participant was social in nature. The social conditions served as the comparison for the alone condition, which included no social consequences for behavior. Lower responding in the alone condition than in the attention or demand conditions would have indicated the need to include a play condition; however, this pattern did not occur.

Figure 1.

Percentage of time samples with vocal stereotypy across alone, attention, and demand conditions of a functional analysis for each participant.

Three conditions were alternated: attention, demand, and alone. In the attention condition, various moderately preferred play materials were available but social interaction was restricted. The experimenter delivered attention in the form of a reprimand (e.g., “Stop that, you're being too loud”) contingent on vocal stereotypy. All other responses were ignored. In the demand condition, the participant was required to complete a task that was considered difficult for his or her skill level (i.e., the task had not yet been mastered during academic instruction). Anna was presented with K-NEX pieces to complete a construction task, Jeff was presented with two-digit math worksheets, and Parker was given a shirt to button. Demands were presented every 15 s, and a two-step prompt hierarchy (i.e., verbal prompt, manual guidance) was used to prompt responding. Social praise was delivered for correct responses. If the participant emitted vocal stereotypy, the therapist stated, “Ok, you don't have to,” and removed the task materials for 15 s. As in the attention condition, all other responses were ignored. During the alone condition, the participant was alone in the room, no materials were present, and no social consequences were delivered.

Baseline

The participant and the experimenter both sat at a table facing the trifold board with pictures. Every 15 s, the experimenter pointed to a preset randomly selected picture on the board for 2 s. If the participant emitted a framed tact, it was followed by verbal praise from the experimenter (e.g., “That's a toy” was followed by “Good job, that is a toy.”). Both prompted (i.e., while experimenter pointed to a picture) and unprompted framed tacts were scored and resulted in verbal praise. Framed mands resulted in the presentation of the item requested. If the item was unavailable, the experimenter responded by stating “Nice job asking, you can have that later.” Unspecified language, stereotypy, and all other responses were ignored.

Tact training

Each participant was taught to tact four items (two preferred stimuli and two common stimuli) from the 34 stimuli on the trifold board. Only four framed tacts were trained, allowing the remaining common stimuli to provide an evaluation of generalization to untrained stimuli. The trifold board was still present in the room, but the photo of the item being trained was removed from the board and held up by the experimenter during training. Sessions were conducted in discrete-trial format with 10 trials per session. Probes were conducted for each potential training item, and tacts that were emitted with 70% or less accuracy were targeted for training. During training, one framed tact was trained to mastery before the next framed tact was targeted. The participant was taught to emit an object label with the autoclitic frame “I see.” Vocal prompts were faded using a four-step prompt hierarchy. Step 1 entailed a full vocal model (“I see [object]”), Steps 2 and 3 entailed a partial vocal model (“I see” then “I”), and, during Step 4, no prompt was delivered. The criterion to increase from one step to the next was 90% accuracy (prompted or unprompted) for one session. The criterion for mastery was 90% accuracy and independence for one session at Step 4. During training, tokens were delivered on a fixed-ratio (FR) 1 schedule (along with social praise) and tokens were exchanged on an FR 10 schedule. Token exchange resulted in the delivery of an edible item paired with social praise. No participants emitted errors during training, and each framed tact was acquired within four 10-trial blocks.

Mand training

Jeff rapidly acquired framed tacts with no significant decrease in vocal stereotypy. However, stereotypy generally occurred at a low level with some variability. Therefore, mand training rather than RIRD was initiated to determine whether additional verbal operant training would further enhance the occurrence of appropriate vocalizations while reducing vocal stereotypy. Mand training was conducted in the same discrete-trial format as tact training, but the participant was taught to emit an object label and the autoclitic frame “I want” to mand for four preferred items. Specific reinforcement (i.e., the item) was delivered on an FR 1 schedule.

Posttact training and postmand training

As in baseline, posttact training (PTT) and postmand training (PMT) sessions lasted 5 min. Prior to PTT and PMT sessions, a primer session was conducted in which the experimenter provided a full vocal model of each of the four trained verbal operants and the participant was required to repeat the model. As in baseline sessions, framed tacts were followed by verbal praise, framed mands for available items were honored, and stereotypy and all other behaviors were ignored.

Response interruption and redirection (RIRD)

Anna and Parker were exposed to this condition. During RIRD sessions, each time the participant emitted vocal stereotypy, the experimenter immediately stopped the session timer and provided prompts for appropriate language in the form of framed tacts. For instance, the experimenter prompted the participant by pointing to a picture of a dog on the board while providing the full vocal model (“I see dog”) until the participant complied by emitting three consecutive correct tacts in the absence of stereotypy. The order of demands was preset from a randomized list, and the experimenter presented both trained framed tacts and untrained framed tacts that had been independently emitted by the participant during previous sessions. At the end of the procedure, the experimenter delivered praise for using appropriate language by stating, “Good job using your words!” However, prompted framed tacts in the context of RIRD did not result in praise. The session timer then was restarted to ensure a 5-min sample for comparison to other conditions. The experimenter's response to framed mands and framed tacts remained the same as in all other conditions and again all other responses were ignored.

In vivo tact training

In vivo tact training occurred with Anna and Jeff, who continued to emit unspecified language at a high rate in the presence of common stimuli. During these training sessions, the same procedures as RIRD were used; however, unlike previous conditions, unspecified language no longer was ignored. If the participant emitted unspecified language at any point during the session, the experimenter provided a full vocal model of the appropriate framed tact, including the unspecified label in conjunction with the autoclitic frame “I see —.”

RESULTS

Results of the functional analysis for each participant supported the hypothesis that vocal stereotypy occurred independently of social consequences. For Anna (Figure 1, top), stereotypy occurred consistently during 30% to 60% of time samples in the alone condition, and a downward trend was evident in the attention condition and much lower stable responding was observed in the demand condition. For Jeff (Figure 1, middle), a similar moderate and variable pattern was observed, with stereotypy occurring during 20% to 60% of time samples in the alone condition. Much lower responding occurred in both the demand and attention conditions. For Parker (Figure 1, bottom), stereotypy did not occur during the demand condition and occurred in the alone and attention conditions with overlapping data paths during the multielement analysis. When consecutive alone sessions occurred beginning with Session 16, stereotypy was observed during a greater percentage of time samples. For each participant, these data suggest that vocal stereotypy occurred at the highest level and most consistently in the alone condition, Moreover, they indicate that stereotypy was not sensitive to social consequences and presumably was maintained by the sensory consequences of vocalizing.

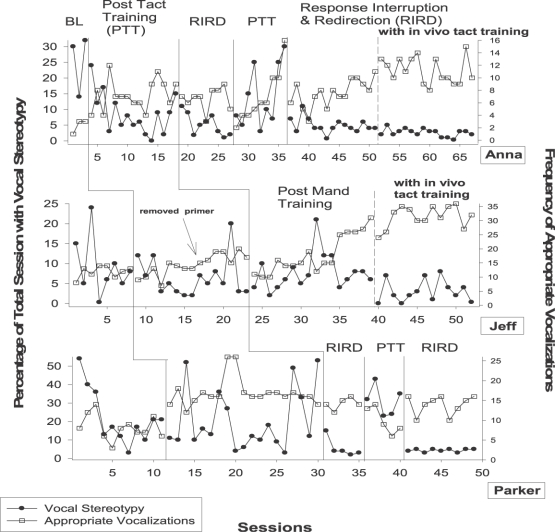

Figure 2 shows the percentage of the total duration of session time with vocal stereotypy (primary y axis) as well as the combined frequency (secondary y axis) of all appropriate vocalizations (i.e., framed mands, framed tacts, unspecified language) for all phases of the treatment analysis. Information about the individual categories of appropriate vocalizations is provided in a subsequent graph. For Anna (top), stereotypy was emitted at a moderate level (M = 25%) and appropriate vocalizations were low (M = 2.3 per session) during the baseline phase. There was an immediate decrease in stereotypy and a sustained increase in appropriate vocalizations (M = 7.3) following tact training. Although the overall levels of stereotypy were lower in the PTT condition (M = 8.6%), the trend was upward in the final sessions. Therefore, RIRD was introduced and further decreased levels of stereotypy (M = 5.2%); appropriate vocalizations were maintained at higher levels than in baseline (M = 5.9). Levels of appropriate vocalizations remained higher than baseline for the remainder of the study, reaching a final stable mean of 11.2 during the last phase. During the reversal to the PTT phase (i.e., removal of RIRD), stereotypy immediately increased to a higher level (M = 14.2%) than in the initial PTT condition. After reintroduction of RIRD, the results were replicated, in that stereotypy immediately decreased (M = 4.8%). Finally, VS remained at near-zero levels during in vivo tact training.

Figure 2.

Percentage of session duration with vocal stereotypy is depicted on the primary y axis. The frequency of appropriate vocalizations (i.e., combined tacts, mands, and unspecified language) across baseline and treatment conditions for each participant is depicted on the secondary y axis. BL = baseline; PTT = posttact training; RIRD = response interruption and redirection.

For Jeff (middle), levels of appropriate vocalizations were moderate (M = 11.9) and levels of stereotypy were low but variable (M = 9.2% of the session, range, 0.3% to 32%) during baseline. Stereotypy decreased with some variability following tact training (M = 6.5%) and appropriate vocalizations slightly increased (M = 14.3) during the PTT condition. Removal of the posttact primer (i.e., full vocal model) prior to Session 17 did not affect the levels of appropriate vocalizations or stereotypy. When mand training was introduced, levels of stereotypy remained highly variable but continued at slightly lower than baseline levels (M = 7.7%, range, 2% to 21%). After mand training, only mands occurred consistently (see below). Appropriate vocalizations initially decreased slightly but then increased to 25 or more vocalizations per session for the last four sessions of this condition. In vivo tact training then was introduced to increase the frequency of framed tacts. Appropriate vocalizations remained high, eventually exceeding 30 per session, and stereotypy decreased to the lowest obtained level with the least variability (M = 3.1%, range, 0% to 8%).

For Parker (bottom), a downward trend from a high to a moderate level of vocal stereotypy was observed throughout the baseline phase (M = 22.2%) while appropriate vocalizations occurred at a variable but moderate level (M = 8.3, range, 3 to 14). Following tact training, stereotypy was highly variable (M = 20.2%, range, 3% to 52%) and periodically occurred at levels that were clinically unacceptable in the last four sessions. Appropriate vocalizations increased to approximately 15 per session in the PTT condition. After RIRD was implemented, there was an immediate decrease in level and variability of stereotypy (M = 5.6%, range, 2% to 15%), and appropriate vocalizations remained stable at 15 per session. When RIRD was removed, there was an immediate increase in stereotypy (M = 31.4%) and a slight decrease in appropriate vocalizations (M = 10). Levels of responding obtained in the previous RIRD condition for both responses were replicated in the last phase of the study, in that stereotypy remained near zero and appropriate vocalizations remained stable at 15 per session.

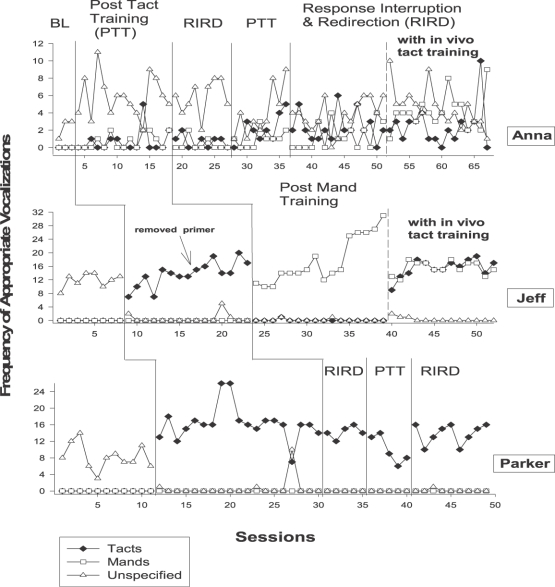

Figure 3 illustrates the frequency of each of the different types of appropriate vocalizations for all phases of the analysis. No participant emitted framed tacts or framed mands during the baseline condition. Anna (top) emitted unspecified language at a moderate to high level (M = 5.9) after initial tact training. Framed tacts emerged and were emitted at low levels (M = 0.7) during the PTT condition, and mands also were emitted infrequently. These patterns continued during the subsequent RIRD phase. After RIRD was removed, framed tacts increased slightly (M = 2), and framed mands (M = 1) and unspecified language (M = 4) remained stable. After reintroduction of RIRD, framed tacts remained low and variable, and framed mands increased slightly but remained infrequent. Anna's framed tacts and framed mands did not increase to moderate levels (Ms = 2.4 and 4.1, respectively) until in vivo tact training was introduced.

Figure 3.

Frequency of appropriate vocalizations by response (i.e., tacts, mands, unspecified language) across baseline and treatment conditions for each participant. BL = baseline; PTT = posttact training, RIRD = response interruption and redirection.

Jeff (middle) emitted unspecified language at a moderate level (M = 11.9) during baseline. Unspecified language then decreased to zero after tact training when framed tacts began to occur (M = 13.8). Unspecified language remained at zero for the remainder of the study. The removal of the primer session did not affect levels of responding, and framed tacts remained stable. Following mand training, framed tacts were virtually eliminated and were replaced by framed mands (M = 0.06 and M = 17.7, respectively). During in vivo tact training, framed tacts increased (M = 15.5) to the level previously observed during the PTT condition, and framed mands remained at high levels (M = 17.7).

Parker (bottom) emitted unspecified language at a moderate level (M = 8.3) during baseline. Similar to Jeff, the initial tact training condition resulted in the immediate emergence of framed tacts (M = 16.3). Framed mands, however, did not emerge during any phase. Framed tacts replaced unspecified language, which remained at zero for the remainder of the study. After implementation of RIRD, responding remained stable as framed tacts continued to be emitted at high levels (M = 14.2). During the final PTT training phase, there was a slight decrease in framed tacts (M = 10). After reimplementation of RIRD, prior levels of responding were recovered (M = 13.8).

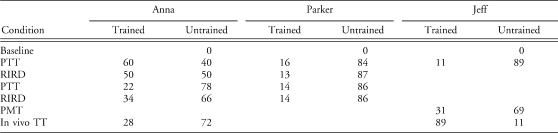

Table 1 presents the proportion of all framed verbal operants that were emitted in each phase and that were trained directly or untrained (i.e., generalized use of autoclitic frame) for each participant. During baseline, no framed verbal operants were emitted by any participant. For Anna, the majority of responses were trained during the initial PTT phase, but the proportion of responses that were untrained equaled or exceeded the trained ones in all remaining phases (i.e., generalized use of “I see” and “ I want” frames). For Jeff and Parker, untrained responses exceeded trained ones throughout the intervention phases, with the exception of Jeff's in vivo tact training phase.

Table 1.

Percentage of Responses Emitted by Participants That Were Trained Directly or Untrained Across Conditions

DISCUSSION

The initial use of response interruption in the behavioral literature targeted motor responses (Hagopian & Adelinis, 2001) and involved response blocking and immediate redirection to a more appropriate activity. Ahearn et al. (2007) described a procedure, termed RIRD, as a practical adaptation of this procedure to target inappropriate vocalizations. RIRD involves presenting vocal demands such as asking social questions to interrupt ongoing vocalizations contingent on the occurrence of vocal stereotypy. RIRD resulted in lower levels of vocal stereotypy and higher levels of appropriate language, although it was not designed to target increases in specific types of appropriate language (i.e., individual verbal operants). The current study extends this work by examining whether purposeful use of verbal operant training might produce similar reductive effects on vocal stereotypy without response interruption while directly improving appropriate functional language.

The current findings suggest that verbal operant training for framed tacts produced an increase in appropriate vocalizations for all three participants; however, the effects on vocal stereotypy were less robust. Vocal stereotypy eventually was observed to occur at low levels for all participants, but clinically acceptable outcomes for this dependent measure required incorporation of RIRD for two of the three participants (Anna and Parker). The implementation of RIRD after verbal operant training decreased stereotypy, and the effects were replicated for both participants. For Anna, tact training and RIRD separately produced mild suppressive effects on stereotypy; however, much greater effects were observed when both components were in place. For Parker, tact training produced a slight reduction in vocal stereotypy, and the implementation of RIRD produced a substantial decrease. Verbal operant training was somewhat more successful in reducing stereotypy for Jeff, who received more extensive training than the other participants (i.e., mand training) and was not exposed to RIRD. These results indicate that establishing specific verbal operants may produce a concomitant decrease in vocal stereotypy, but the conditions under which effects are observed are not clearly discernible and may be idiosyncratic. It should be noted, however, that the additional mand training did not reduce Jeff's stereotypy to the extent that RIRD did with the other two participants.

Similar to Ahearn et al. (2007), RIRD was successful in reducing vocal stereotypy in both cases, thus providing additional support for the clinical usefulness of the procedure. However, RIRD was always implemented after verbal operant training, and it is unclear what effect RIRD may have had if verbal operant training had not been conducted first. The finding with Jeff also provides limited support for other studies that indicate that effective instruction and acquisition of skills may aid indirectly in the treatment of vocal stereotypy (Dib & Sturmey, 2007; Pierce & Schreibman, 1994). However, given the mixed findings regarding verbal operant training in the present study, additional research is warranted to investigate the potential positive collateral effects of skill acquisition on problem behaviors.

Our verbal operant training targeted tacts and mands that included an autoclitic frame, because an autoclitic frame clarifies the function of the verbal operant for the listener (Skinner, 1957). Baseline responding of unspecified vocalizations indicated that the three participants in this study were able to label stimuli in the environment prior to treatment; however, the function of these vocalizations was unclear (i.e., possibly unframed tacts, possibly unframed mands that had been reinforced previously). These unframed vocalizations made it difficult for the listener to respond effectively to the speaker (i.e., Do they want the item or are they just commenting on it?). Verbal operant training served to increase the clarity of subsequent verbal utterances for the listener, thereby increasing the likelihood of naturally occurring reinforcement for utterances that occurred outside the explicit training context. The establishment of the autoclitic frame for trained tact targets resulted in generalized use of the frame with other labels that were emitted in baseline without the frame. Furthermore, the unprompted emergence of framed mands (i.e., “I want —”) following tact training (i.e.,“I see a —”) was observed only for Anna. For Jeff, framed mands emerged after mand training and eliminated the framed tacts. It was only through the introduction of in vivo tact training that both framed verbal operants were emitted reliably. In the case of Parker, framed mands did not emerge after tact training and were not trained explicitly. It is unknown whether the unspecified language that occurred in baseline had functional properties consistent with unframed mands or tacts, because we did not conduct functional analyses of those object label responses. Future studies might include a functional analysis of unspecified language based on the procedures described by Lerman et al. (2005).

The redirection component of RIRD involved prompting participants to emit framed tacts of stimuli that had been trained during the study or existed in their repertoire prior to the study, and the completion of each RIRD procedure resulted in verbal praise from the experimenter. Because these demands were presented contingent on vocal stereotypy, RIRD may operate according to a punishment contingency (Lerman & Iwata, 1996) akin to a positive practice procedure. Foxx and Betchel (1983) suggested that reinforcement of correct performance during a positive practice procedure may increase inappropriate behavior. However, this study suggests that RIRD did not have a suppressive effect on appropriate vocalizations, nor did it increase inappropriate behavior despite reinforcement for appropriate vocalizations. In addition, although positive practice procedures target a decrease in inappropriate behavior, they also have been correlated with an increase in appropriate behavior (Barton & Osborne, 1978; Carey & Bucher, 1981; Foxx, 1977). This may account for the findings of the Ahearn et al. (2007) study in which appropriate vocalizations increased as a positive side effect of RIRD.

Two limitations of the current study were the lack of standardized measures to assess intellectual or adaptive functioning levels of our participants and the lack of a structured assessment of the verbal operants such as those found in Partington (2006) and Sundberg (2008). The results of these types of assessments might have shed light on the repertoires that affect whether verbal operant training has any impact on vocal stereotypy. Future studies should include these types of measures to provide comprehensive information about participants' repertoires. Another limitation was the lack of a full functional assessment due to the omission of the play condition, which typically serves as the control condition. In our prior published research we have used this same procedure, but it does represent a slight departure from traditional functional analysis research. Finally, our current research design did not provide a full reversal for every experimental manipulation (e.g., in vivo mand training), which limits the degree to which we can draw conclusions about the unique effects of each component.

The effectiveness of RIRD in conjunction with verbal operant training may have potential implications for instruction in classroom settings, although the current study was conducted in a more controlled, individual instructional setting. Although RIRD can be effective in reducing vocal stereotypy when implemented without verbal operant training, this study suggests that verbal operant training is a useful complementary procedure that may affect stereotypy as well as enhance the individual's verbal repertoire. Teachers and professionals who work with children with ASD should provide an enriched environment (i.e., many interesting items that might evoke tacts or mands) and take every opportunity to teach appropriate verbal behavior in addition to using RIRD to decrease inappropriate vocalizations.

Acknowledgments

We thank the New England Center for Children and Northeastern University for their continuous contributions to the field of applied behavior analysis. We extend appreciation to Katherine Bowza, Tiffany Negus, and Christine Ryan for their help with data collection and interobserver agreement.

REFERENCES

- Ahearn W.H, Clark K, MacDonald R, Chung B.I. Assessing and treating vocal stereotypy in children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:263–275. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.30-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton E.J, Osborne J.G. The development of classroom sharing by a teacher using positive practice. Behavior Modification. 1978;2:231–250. [Google Scholar]

- Carey R.G, Bucher B.D. Identifying the educative and suppressive effects of positive and restitutional overcorrection. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1981;14:71–80. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1981.14-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dib N, Sturmey P. Reducing student stereotypy by improving teachers' implementation of discrete-trial teaching. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:339–343. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.52-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap G, Dyer K, Kogel R.L. Autistic self-stimulation and intertrial interval duration. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 1983;88:194–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellner D.J, LaRoche M, Sulzer-Azaroff B. The effects of adding interruption to differential reinforcement on targeted and novel self-stimulatory behaviors. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1984;4:315–321. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(84)90095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W.W, Piazza C.C, Bowman L.G, Hagopian L.P, Owens J.C, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe to profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxx R.M. Attention training: The use of overcorrection avoidance to increase the eye contact of autistic and retarded children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1977;10:489–499. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1977.10-489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxx R.M, Betchel D.R. Overcorrection: A review and analysis. In: Axelrod S, Apsche J, editors. The effects of punishment on human behavior. New York: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 133–220. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Gardenier N.C, MacDonald R, Green G. Comparison of direct observational methods for measuring stereotypic behavior in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2004;25:99–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2003.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian L.P, Adelinis J.D. Response blocking with and without redirection for the treatment of pica. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34:527–530. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B.A, Dorsey M.F, Slifer K.J, Bauman K.E, Richman G.S. Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:197–209. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197. (Reprinted from Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 2, 3–20, 1982) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R.S.P, Wint D, Ellis N.C. The social effects of stereotyped behaviour. Journal of Mental Deficiency Research. 1990;34:261–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1990.tb01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laraway S, Snycerski S, Michael J, Poling A. Motivating operations and terms to describe them: Some further refinements. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:407–414. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman D.C, Iwata B.A. A methodology for distinguishing between extinction and punishment effects associated with response blocking. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:231–233. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman D.C, Parten M, Addison L, Vorndran C, Volkert V, Kodak T. A methodology for assessing the functions of emerging speech in children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:303–316. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.106-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M.H, Bodfish J.W. Repetitive behavior disorders in autism. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 1998;4:80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lovaas I, Newsom C, Hickman C. Self-stimulatory behavior and perceptual reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1987;20:45–68. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1987.20-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald R, Green G, Mansfield R, Geckeler A, Gardenier N, Anderson J, et al. Stereotypy in young children with autism and typically developing children. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2006;28:266–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMorrow M.J, Foxx R.M. Some direct and generalized effects of replacing an autistic man's echolalia with correct responses to questions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1986;19:289–297. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1986.19-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael J. Establishing operations and the mand. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1988;6:3–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03392824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partington J.W. The Assessment of Language and Learning Skills-Revised (the ABLLS-R): An assessment, curriculum guide and skills tracking system for children with autism or other developmental disabilities. Walnut Creek, CA: Behavior Analysts Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce K.L, Schreibman L. Teaching daily living skills to children with autism in unsupervised settings through pictorial self-management. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:471–481. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rincover A. Sensory extinction: A procedure for eliminating self-stimulatory behavior in developmentally disabled children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978;6:299–310. doi: 10.1007/BF00924733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe E, Carreau A, MacDonald J, Pence S. Further evaluation of leisure items in the attention condition of functional analyses. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41:351–364. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreibman L, Carr E.G. Elimination of echolalic responding to questions through the training of a generalized verbal response. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1978;11:453–463. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1978.11-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Verbal behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Smith E.A, Van Houten R. A comparison of the characteristics of self-stimulatory behavior in “normal” children and children with developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 1996;17:253–268. doi: 10.1016/0891-4222(96)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R.G, Russo L, Le D.D. Distinguishing between extinction and punishment effects of response blocking: A replication. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32:367–370. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg M.L. The Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program: The VB-MAPP. Concord, CA: AVB Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg M.L, Michael J. The benefits of Skinner's analysis of verbal behavior for children with autism. Behavior Modification. 2001;25:698–724. doi: 10.1177/0145445501255003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B.A, Hoch H, Weisman M. The analysis and treatment of vocal stereotypy in a child with autism. Behavioral Interventions. 2005;20:239–253. [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer T.R. The concept of automatic reinforcement: Implications for behavioral research in developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 1994;15:187–207. doi: 10.1016/0891-4222(94)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]