Abstract

After a 3-step guided compliance procedure (vocal prompt, vocal plus model prompt, vocal prompt plus physical guidance) did not increase compliance, we evaluated 2 modifications with 4 preschool children who exhibited noncompliance. The first modification consisted of omission of the model prompt, and the second modification consisted of omitting the model prompt and decreasing the interprompt interval from 10 s to 5 s. Each of the modifications effectively increased compliance for 1 participant. For the remaining 2 participants, neither modification was effective; differential reinforcement in the form of contingent access to a preferred edible item was necessary to increase compliance. Problem behavior varied across participants, but was generally higher during guided compliance conditions and lower during differential reinforcement conditions.

Keywords: compliance, guided compliance, noncompliance, physical guidance, preschoolers, prompting

Noncompliance is defined as the failure to follow a specific teacher- or caregiver-delivered instruction (Forehand, Gardner, & Roberts, 1978). Although estimates vary, noncompliance has been reported to occur in up to half of children between the ages of 15 months and 4 years and is the most common childhood behavior problem for which treatment is sought (Bernal, Klinnert, & Schultz, 1980). In addition, noncompliance at a young age is correlated with a number of psychiatric diagnoses later in life, such as oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder (Keenan, Shaw, Delliquadri, Giovannelli, & Walsh, 1998).

Interventions to increase compliance, and thus address noncompliance, have been organized into two categories. Antecedent-based interventions precede the opportunity for the child to comply. Examples of antecedent-based interventions include advance notice, rationales, and the high-probability (high-p) instructional sequence. Advance notice consists of a warning that an instruction that will necessitate a change in activity or setting is forthcoming. Results from three studies that evaluated advance notice to increase compliance suggest that it is often ineffective (Cote, Thompson, & McKerchar, 2005; Wilder, Nicholson, & Allison, 2010; Wilder, Zonneveld, Harris, Marcus, & Reagan, 2007). Rationales are statements describing the reasons why a child should comply with an adult-delivered instruction (e.g., “Your father will be home soon and might step on your toys. Pick them up.”). Wilder, Allison, Nicholson, Abellon, and Saulnier (2010) found that rationales did not increase compliance for six preschool children. The high-p instructional sequence consists of a series of requests to which the child is likely to comply (i.e., high-p requests) immediately followed by a low-probability target instruction. The high-p instructional sequence has received mixed empirical support; some studies have shown that it is effective in increasing compliance (e.g., Mace et al., 1988) and others have not (e.g., Rortvedt & Miltenberger, 1994).

Consequence-based interventions involve the delivery or removal of a stimulus after compliance or noncompliance. Common consequence-based interventions include differential reinforcement and time-out from positive reinforcement (e.g., Bouxsein, Roane, & Harper, 2011). Differential reinforcement involves the delivery of praise, edible items, or tangible items contingent on compliance. Baer, Rowbury, and Baer (1973) successfully used tokens, which were exchangeable for snacks and preferred tangible items, to differentially reinforce compliance by three preschool children. Time-out from positive reinforcement consists of removing access to positive reinforcement for a specified time period contingent on noncompliance. Rortvedt and Miltenberger (1994) used time-out to increase compliance of two children after a high-p sequence was ineffective for one participant. Although consequence-based interventions generally have been more effective than antecedent-based procedures, they are not without drawbacks. For example, some early childhood settings prohibit the use of time-out. Thus, additional research on interventions to increase compliance is warranted.

Three-step guided compliance commonly is used to increase compliance. First described by Horner and Keilitz (1975) to teach adolescents with intellectual disabilities to brush their teeth, the procedure includes both antecedent- and consequence-based components. The first step of this procedure is the delivery of a vocal prompt (e.g., “Pick up your toy”). If the child complies, the caregiver delivers praise. If the child does not comply within 10 s, the caregiver repeats the vocal prompt and models the correct performance. If the child complies, praise is delivered. If the child does not comply within 10 s, the caregiver repeats the vocal prompt a third time while simultaneously guiding the child to comply with the instruction.

Previous research has shown that the three-step guided compliance procedure can increase compliance. For example, Wilder and Atwell (2006) evaluated the procedure with six preschool children who exhibited noncompliance and found that it was effective for four participants. Tarbox, Wallace, Penrod, and Tarbox (2007) evaluated the three-step guided compliance procedure with five child–caregiver dyads. They found that the procedure decreased the frequency of caregiver prompts and increased compliance in all five children.

Although the three-step guided compliance procedure has been shown to be effective, it may not be effective in all cases (Wilder & Atwell, 2006) or may take a large number of trials to be effective. Under these circumstances, modifications to the procedure may be necessary to achieve acceptable levels of compliance. The purpose of the current study was to evaluate two modifications to the three-step guided compliance procedure after it initially proved to be ineffective with four preschool children.

METHOD

Participants and Setting

Four children participated in the study. Carl, Max, and Mike were 4-year-old boys. Ann was a 3-year-old girl. All participants had age-appropriate language skills, and none had a psychiatric diagnosis or a developmental disability. Before the study began, teachers reported that all participants were noncompliant, particularly when asked to surrender a preferred toy. This is a naturally occurring instruction often delivered to preschool children when it is time to clean up toys and when they are required to share or take turns playing with toys. A female graduate student, unfamiliar to participants when the study began, served as the experimenter for all sessions. One to two other graduate students, but no other children, were in the room during sessions. Four to eight sessions were conducted per day, 2 days per week. Sessions took place in a small room at the participants' school.

Response Measurement and Definitions

Data were collected on the occurrence or nonoccurrence of both compliance and problem behavior during each trial. Compliance was defined as initiation or completion (within 10 s) of the activity described in the instruction delivered to participants. Thus, compliance was recorded if the child initiated the instruction within 10 s and completed the task by the end of the trial. Problem behavior was defined as aggression (e.g., hitting, pinching, kicking), property disruption or destruction (e.g., throwing toys, hitting objects), and whining, crying, or saying “no” to the experimenter.

Interobserver Agreement and Treatment Integrity

A second independent observer recorded compliance and problem behavior on at least 60% of trials for all participants. Interobserver agreement data were obtained by comparing the data each observer collected on a trial-by-trial basis. Agreements were defined as trials in which both observers agreed that the target behavior occurred or did not occur. Mean agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100%. Agreement values for compliance ranged from 90% to 100% for all participants. For problem behavior, agreement values ranged from 82% to 100% for all participants.

Data on the integrity of the independent variable were collected by recording the delivery of the appropriate prompt (i.e., verbal, model, physical guidance) at the appropriate time (i.e., 10 s after the previous prompt) during the three-step and two-step procedures and the delivery of the edible item within 3 s during the differential reinforcement procedure (Mike and Ann). Integrity data were calculated by dividing the number of correct deliveries by the number of correct plus incorrect deliveries (i.e., all opportunities for the experimenter to prompt or reinforce) and multiplying by 100% for each session. Integrity values ranged from 98% to 100% across all sessions for all participants. Finally, interobserver agreement data on integrity of the independent variable were collected by having a second observer record prompt and edible item deliveries on a trial-by-trial basis during at least 20% of sessions for all participants. Agreement between the two observers was calculated per session by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100%. A mean agreement score then was obtained by summing the session agreement values and dividing that sum by the number of sessions agreement data were collected; agreement values were 100%.

Procedure

Separate paired-stimulus preference assessments (Fisher et al., 1992) were conducted for toys and edible items for each participant. Preferred toys for Carl, Max, Mike, and Ann were a toy motorcycle, a Power Ranger figure, a Transformer, and a toy hamster, respectively. Preferred edible items for Carl, Max, Mike, and Ann were gummies, sour gummies, Doritos, and Smarties, respectively.

Each trial consisted of a 1-min preinstruction period, the presentation of the instruction, and a 1-min postinstruction period. Each session consisted of five trials. Reversal designs were used to evaluate the effects of three-step prompting, modifications to it (i.e., elimination of the model prompt, reduction of interprompt interval), and differential reinforcement on compliance and problem behavior. During baseline, participants had access to their most preferred toy, identified via the stimulus preference assessment, and the experimenter presented the instruction “Give me the [toy].” Compliance resulted in the experimenter saying “thank you,” and the child was free to do whatever he or she liked during the 1-min postinstruction period, but no other toys were available. If the child did not comply, the experimenter did nothing (i.e., did not say anything or remove the toy) for the remainder of the 1-min postinstruction period.

During the three-step guided compliance condition, the experimenter presented the initial instruction as in baseline. If the participant did not comply within 10 s, the experimenter repeated the instruction while obtaining eye contact with the participant and modeling giving a toy. The experimenter modeled giving a separate toy to herself. If the participant complied after the first or second step, the experimenter said “thank you.” If the participant did not comply within 10 s after the model prompt, the experimenter repeated the instruction a third time and physically guided the participant to comply with the instruction. Compliance was scored only if the participant gave the experimenter the toy following the initial instruction.

During the first modification of the three-step guided compliance procedure (i.e., two-step), the model prompt was eliminated (i.e., the three-step procedure became a two-step procedure). This modification was selected because, for some children, providing the model prompt may simply prolong access to the toy. In addition, the purpose of the model prompt is to demonstrate how to perform the behavior being requested by the therapist. The model prompt may not be necessary for children with adequate listener repertoires. The experimenter presented the initial instruction as in the three-step procedure described above, but if the participant did not comply within 10 s, the experimenter repeated the instruction while physically guiding the participant to comply. If the participant complied within 10 s of the initial instruction, the experimenter said “thank you.” Compliance was scored if the participant gave the experimenter the toy on the first delivery of the instruction only.

During the second modification of the three-step procedure (i.e., two-step guided compliance with 5-s interprompt interval), the two-step procedure remained in place, but the interval between prompts was reduced from 10 s to 5 s. This modification was made to reduce further the time between the initial request and the point at which the child had to relinquish the toy. The experimenter presented the initial instruction, but if the participant did not comply within 5 s, the experimenter repeated the instruction while physically guiding the participant to comply. If the participant complied within 5 s of the initial instruction, the experimenter said “thank you.” Compliance was scored only if the participant gave the experimenter the toy on the first delivery of the instruction.

During the differential reinforcement condition, the experimenter presented the instruction to give her the toy while holding a small piece of each participant's most preferred edible item. If the participant complied within 10 s, the experimenter immediately delivered the edible item. If the participant did not comply with the instruction, the experimenter did nothing (i.e., provided no prompts and did not remove the toy) for the remainder of the 1-min postinstruction period.

RESULTS

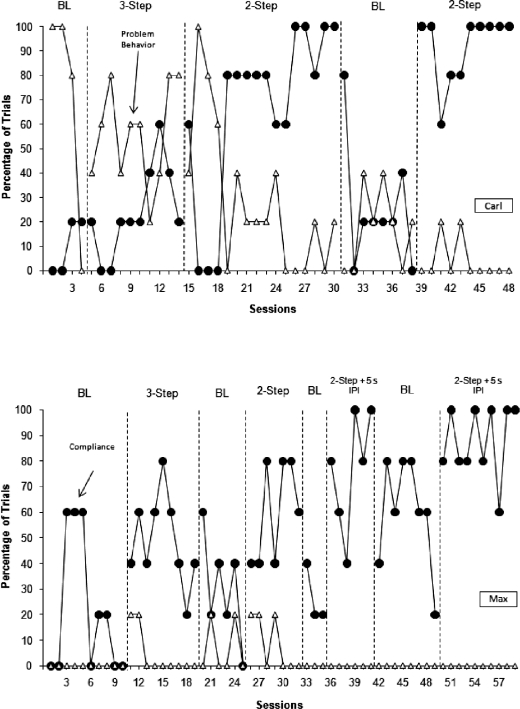

The figures depict the results of the evaluation of the three-step guided compliance procedure, modifications to it (i.e., elimination of the model prompt, reduction of the interprompt interval), and differential reinforcement on compliance. Carl's compliance (Figure 1, top) was low during baseline (M = 10%, SD = 11.5% and M = 25%, SD = 25.5% during the first and second baseline conditions, respectively) and three-step guided compliance conditions (M = 24%; SD = 18.4%). His compliance increased substantially during the first two-step guided compliance condition (i.e., when the model prompt was omitted; M = 66.3%; SD = 35.6%) and increased even more during the second two-step guided compliance condition (M = 92%; SD = 13.9%). Carl's problem behavior was most frequent during the first baseline condition (M = 70%; SD = 47.6%) and the three-step guided compliance condition (M = 56%; SD = 20.6%). His problem behavior occurred less often during the second baseline condition (M = 17.5%; SD = 16.7%) and the first (M = 28.8%; SD = 30.1%) and second (M = 4%; SD = 8.4%) two-step guided compliance conditions.

Figure 1.

Percentage of trials with compliance and problem behavior across baseline (BL), three-step guided compliance (3-Step), and guided compliance with model prompt omitted (2-Step) for Carl (top). Guided compliance with model prompt omitted and reduced interprompt interval (2-Step + 5 s IPI) is depicted for Max (bottom).

Max's compliance (Figure 1, bottom) was relatively low during baseline (M = 22%, SD = 27.4%; M = 30%, SD = 21%; M = 26.7; SD = 11.4%; and M = 60%, SD = 21.3% for the first, second, third, and fourth baseline conditions, respectively), as well as the three-step guided compliance condition (M = 48.8%; SD = 17.6%). His compliance increased slightly during the two-step guided compliance condition (M = 60%; SD = 20%), and increased more during the first (M = 76.6%; SD = 23.3%) and second (M = 88%; SD = 13.9%) two-step conditions with a 5-s interprompt interval. Max's problem behavior occurred very infrequently throughout all conditions.

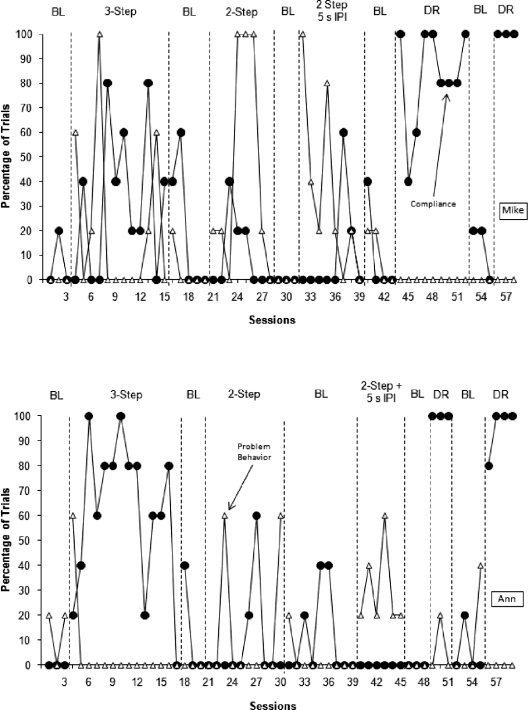

Mike (Figure 2, top) did not comply often during baseline (M = 6.7%, SD = 11.5%; M = 20%, SD = 28.3%; M = 0%, SD = 0%; M = 10%, SD = 20%; and M = 13.3%, SD = 11.5% for the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth baseline conditions, respectively). During the three-step guided compliance condition, compliance increased slightly (M = 31.7%; SD = 30.1%), but did not occur at clinically acceptable levels. Compliance remained low during the two-step guided compliance condition (M = 10%; SD = 15.1%) and during the two-step guided compliance plus 5-s interprompt interval condition (M = 10%; SD = 21.3%). During the differential reinforcement conditions, Compliance increased substantially and remained at high levels (M = 82.2%, SD = 21.1%; M = 100%, SD = 0% for the first and second differential reinforcement conditions, respectively). Mike's problem behavior was infrequent during all baseline and differential reinforcement conditions. He did exhibit higher levels of problem behavior during the three-step guided compliance condition (M = 21.6%; SD = 33.5%), the two-step guided compliance condition (M = 45%; SD = 45.9%), and the two-step guided compliance condition with 5-s interprompt interval (M = 35%; SD = 36.6%).

Figure 2.

Percentage of trials with compliance and problem behavior across baseline (BL), three-step guided compliance (3-Step), guided compliance with model prompt omitted (2-Step), guided compliance with model prompt omitted and reduced interprompt interval (2-Step + 5 s IPI), and differential reinforcement (DR) for Mike (top) and Ann (bottom).

Ann's compliance (Figure 2, bottom) was also low during baseline (M = 0%, SD = 0%; M = 10%, SD = 20%; M = 11.1%, SD = 17.6%; M = 0%, SD = 0%; and M = 5%, SD = 10% for the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth baseline conditions, respectively). Her compliance initially improved during the first three-step guided compliance condition, but then decreased (M = 61.4%; SD = 30.8%). Compliance remained low during the two-step condition (M = 8.8%; SD = 20.2%) and during the two-step condition with the 5-s interprompt interval (M = 0%; SD = 0%). During the differential reinforcement condition, compliance increased substantially and remained at high levels (M = 100%, SD = 0% and M = 95%, SD = 10% for the first and second differential reinforcement conditions, respectively). Ann's problem behavior was relatively infrequent throughout all conditions, but did occur during the two-step guided compliance condition with the 5-s interprompt interval (M = 30%; SD = 16.7%).

DISCUSSION

Results of this study suggest that the three-step guided compliance procedure could be modified to increase its effectiveness for some children. The two modifications examined in this study, omitting the model prompt and decreasing the interprompt interval, were each effective for one participant. Differential reinforcement in the form of contingent access to a preferred edible item was necessary to increase compliance for the remaining two participants. The effects of omitting the model prompt and decreasing the interprompt interval for Carl and Max must remain tentative, however, because these modifications were not isolated in the experimental design. That is, we reversed to baseline instead of reversing by removing the manipulation and then replicating the effect. An alternative explanation of the results is that continued exposure to physical guidance and reinforcement was responsible for the increase in compliance.

Problem behavior varied across participants. For Carl, problem behavior was most frequent during the initial three-step guided compliance condition. Max exhibited very little problem behavior in any condition. Mike and Ann exhibited high levels of problem behavior in the two-step and two-step with reduced interprompt interval conditions. The most common topography of problem behavior was saying or yelling “no,” although some physical aggression was exhibited. Problem behavior was lowest during the differential reinforcement conditions (Mike and Ann), as might be expected because compliance produced access to a preferred edible item.

The behavioral mechanisms that are responsible for the effectiveness of the three-step guided compliance procedure probably vary by child and by application. The instructions and the model prompt may serve as discriminative stimuli, signaling the availability of reinforcement for compliance. Alternatively, compliance may increase due to consequences provided for compliance and noncompliance. Some children's behavior may be controlled by negative reinforcement. That is, for some children, the last step of the three-step guided compliance procedure (i.e., physical guidance) may be aversive enough to evoke behavior that will function to avoid such a consequence. For others, the “thank you” delivered contingent on compliance at the first step may function as positive reinforcement. Finally, a combination of these may be responsible for increasing compliance in some children.

Omission of the model prompt might have increased compliance because the spoken instructions acquired discriminative properties more readily when the ratio of instructions to physical guidance was decreased. That is, when the model prompt was used, the child was told to complete the task three separate times. For some children, repeatedly hearing the instruction without being required to complete the task may decrease the likelihood that the instruction will acquire stimulus control over the response (i.e., compliance). During two-step guided compliance, only one opportunity to comply was available before physical guidance occurred. This might strengthen stimulus control by the initial instruction.

If its purpose is to demonstrate what is being requested in the instruction, the model prompt may be necessary only for very young children or children with intellectual disabilities. That is, children with an adequate listener repertoire may not require the model prompt, particularly for single-step or straightforward instructions. Relative to three-step guided compliance, omission of the model prompt also requires less time and effort for caregivers.

Reducing the interprompt interval may have increased the effectiveness of the consequence that followed each instruction. Specifically, the decreased interprompt interval shortened the latency to physical guidance following an instance of noncompliance. This modification may have increased the potential punishing effects of physical guidance and evoked compliance that resulted in avoidance of physical guidance. In the current study, noncompliance resulted in continued access to a highly preferred item; therefore, it may have been particularly important to enhance the effectiveness of programmed consequences for compliance and noncompliance.

In many cases, differential reinforcement or contingent access to preferred items might be considered as the first choice of interventions to address compliance, rather than as a back-up procedure. Differential reinforcement is arguably less intrusive than guided compliance and may be more socially acceptable. Although teachers and parents commonly may use differential reinforcement to increase compliance, they may not deliver highly preferred items or activities differentially, as was the case in this study.

Contingent access to preferred edible (or other) items also could be added to an existing three-step or two-step guided compliance procedure. Although this was considered for Mike and Ann, contingent access alone was chosen due to concerns that the guided compliance component of the two-step procedure might function as a reinforcer for noncompliance for these two participants; they often smiled during physical guidance. The extent to which physical guidance is permitted in a given setting or preferred by a child is a very important consideration in determining whether or not to use guided compliance.

No assessment was conducted to identify the variables that maintained noncompliance. Although it may not be practical to conduct a functional analysis of noncompliance for every child who is noncompliant, the mixed results obtained in this study suggest a need to better understand the conditions under which modifications to three-step compliance or other interventions are necessary. Future research might include a functional analysis of noncompliance similar to the one conducted by Rodriguez, Thompson, and Baynham (2010).

One consideration when using differential reinforcement is how best to thin the schedule of delivery of preferred items. Due to time constraints, we were unable to thin the schedule in this study, although previous research has accomplished schedule thinning successfully (Wilder, Allison, et al., 2010). Future research should examine further the thinnest reinforcement schedule at which compliance can be maintained. Another consideration is the social acceptability of using edible items, particularly in school settings. Future research should examine the use of alternatives to edible items, such as tokens exchangeable for classroom privileges (McLaughlin & Malaby, 1972).

The current study evaluated guided compliance and differential reinforcement interventions under a restricted set of conditions. That is, these interventions were evaluated for noncompliance that occurred in the context of a therapist requesting a preferred item. Future research also should evaluate the interventions examined in this study under a wider variety of conditions and determine whether there are any collateral benefits to improving compliance among young children. For example, it is possible that improvement in either academic performance or compliance in other contexts might result from directly increasing compliance. Finally, future research should evaluate the acceptability and likelihood of adoption of guided compliance procedures. Addressing the barriers to getting these interventions into the hands of teachers and parents is an important step to increasing their use.

REFERENCES

- Baer A.M, Rowbury T, Baer D.M. The development of instructional control over classroom activities of deviant preschool children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1973;6:289–298. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1973.6-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal M.E, Klinnert M.D, Schultz L.A. Outcome evaluation of behavioral parent training and client-centered parent counseling for children with conduct problems. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1980;13:677–691. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1980.13-677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouxsein K.J, Roane H.S, Harper T. Evaluating the separate and combined effects of positive and negative reinforcement in task compliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44:175–179. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote C.A, Thompson R.H, McKerchar P.M. The effects of antecedent interventions and extinction on toddlers' compliance during transitions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:235–238. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.143-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza C.C, Bowman L.G, Hagopian L.P, Owens J.C, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Gardner H, Roberts M.W. Maternal response to child compliance and noncompliance: Some normative data. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1978;7(2):121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Horner R.D, Keilitz I. Training mentally retarded adolescents to brush their teeth. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1975;8:301–309. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1975.8-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Shaw D, Delliquadri E, Giovannelli J, Walsh B. Evidence for the continuity of early problem behaviors: Application of a developmental model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:441–454. doi: 10.1023/a:1022647717926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace F.C, Hock M.L, Lalli J.S, West B.J, Belfiore P, Pinter E, et al. Behavioral momentum in the treatment of noncompliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1988;21:123–141. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1988.21-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin T, Malaby J. Intrinsic reinforcers in a classroom token economy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1972;5:263–270. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1972.5-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez N, Thompson R, Baynham T. Assessment of the relative effects of attention and escape on noncompliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:143–147. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rortvedt A.K, Miltenberger R.G. Analysis of a high-probability instructional sequence and time-out in the treatment of child noncompliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:327–330. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarbox R.S.F, Wallace M.D, Penrod B, Tarbox J. Effects of three-step prompting on compliance with caregiver requests. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:703–706. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.703-706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder D.A, Allison J, Nicholson K, Abellon O.E, Saulnier R. Further evaluation of antecedent interventions on compliance: The effects of rationales to increase compliance among preschoolers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:601–613. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder D.A, Atwell J. Evaluation of a guided compliance procedure to reduce noncompliance among preschool children. Behavioral Interventions. 2006;21:265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Wilder D.A, Nicholson K, Allison J. An evaluation of advance notice to increase compliance among preschoolers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:751–755. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder D.A, Zonneveld K, Harris C, Marcus A, Reagan R. Further analysis of antecedent interventions on preschoolers' compliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:535–539. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.40-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]