Abstract

We compared the effectiveness of three training procedures, echoic and tact prompting plus error correction and a cues-pause-point (CPP) procedure, for increasing intraverbals in 2 children with autism. We also measured echoic behavior that may have interfered with appropriate question answering. Results indicated that echoic prompting with error correction was most effective and the CPP procedure was least effective for increasing intraverbals and decreasing echoic behavior.

Keywords: acquisition, autism, echoic behavior, error correction, intraverbal training, verbal behavior

Development of an intraverbal repertoire has been overlooked often in early intervention (EI) programs for children with autism (Sundberg & Michael, 2001). An intraverbal is a verbal operant that is evoked by a verbal discriminative stimulus that lacks formal similarity to the response (Skinner, 1957). For example, “What says meow?” might evoke the response “cat.”

Previous research on intraverbal training techniques evaluated transfer of stimulus control procedures (e.g., Ingvarsson & Hollobaugh, 2011). That is, stimulus control was transferred from an echoic (a verbal operant controlled by a verbal discriminative stimulus that has point-to-point correspondence with the response; Skinner, 1957) or tact (a verbal operant occasioned by a nonverbal stimulus; Skinner, 1957) to an intraverbal. Previous studies have compared echoic- and tact-to-intraverbal procedures plus error correction and found both treatments to be effective for teaching intraverbals (Ingvarsson & Hollobaugh, 2011). However, tact prompts cannot be used for training intraverbals when the response does not have an associated nonverbal stimulus (e.g., the response “moo” to the question “What does a cow say?”). Echoic prompts may produce echoic behavior that is occasioned by any vocal verbal stimulus due to a lack of stimulus control. For example, an individual may answer “name” in response to the question “What is your name?” (e.g., McMorrow, Foxx, Faw, & Bittle, 1987).

Another intervention that has been found to be effective for increasing intraverbals is a cues-pause-point (CPP) procedure (McMorrow et al., 1987). A potential advantage of this intervention is that it includes components for reducing echoic behavior that is under faulty stimulus control. For example, the therapist presents a prompt for the participant to remain quiet immediately prior to presenting the discriminative stimulus for a correct response.

We sought to compare the effectiveness of three intraverbal training procedures for increasing intraverbal behavior. We also measured echoic behavior to determine whether echoics may have interfered with the acquisition of intraverbal responses.

METHOD

Participants, Setting, and Materials

Two individuals with autism who received services in a hospital-based EI program participated. Adam and Eric were 4 and 5 years old, respectively. Both participants had acquired more than 150 mands and tacts during their admission to the EI program, and they frequently repeated portions of questions during intraverbal training. We successfully used echoic and tact prompts in prior intraverbal training with both participants to teach at least 10 intraverbals, although participants required extended training time due to echoic behavior. Neither participant had been exposed to CPP.

The therapist conducted sessions in a private therapy room that contained all relevant session materials. During treatment sessions, the therapist presented pictures of common items that were used as tact prompts. A manila folder (22 cm by 28 cm) covered the picture during a portion of trials in the CPP condition.

Response Measurement and Interobserver Agreement

The primary dependent variables were correct unprompted responses and echoics. A correct unprompted response was defined as the participant providing a relevant answer to the question prior to a prompt. The response was not considered correct if the participant added words to the correct answer or emitted an echoic response. An echoic response was defined as repeating a word or words from the therapist's question (e.g., answering “moo cow” when asked “What says moo?”). We converted each dependent variable to a percentage by dividing the number of occurrence trials by the total number of trials in a session and multiplying the quotient by 100%.

Two independent observers collected data on each dependent variable on a trial-by-trial basis during 63% and 50% of Adam's and Eric's sessions, respectively. We calculated interobserver agreement by comparing observers' records for each trial in a session, dividing the number of trials in which both observers scored an occurrence of the target behavior by the total number of trials in the session, and converting this ratio to a percentage. The mean agreement for all dependent variables was 100% for Adam and Eric.

Procedure

The therapist conducted one to three sessions per day, 3 to 5 days per week. Each session consisted of 12 trials. Each condition contained a different set of three target intraverbals presented in a random order four times per session. We selected targets based on the participants' current educational goals and assigned targets to conditions to equate the length of responses and types of questions. We conducted probes to ensure that the participants had not acquired the target intraverbals and could tact pictures corresponding to correct responses.

The therapist conducted treatment sessions until correct unprompted responding reached the mastery criterion (i.e., two consecutive sessions with correct unprompted responding above 90%) or until all targets were acquired in at least one treatment condition. If the participant had not yet reached mastery-level responding in one condition following mastery of targets in another condition, the therapist implemented the condition that produced the most rapid acquisition. We evaluated the effectiveness of three interventions on correct intraverbal responses and echoic behavior with an adapted alternating treatments design (Sindelar, Rosenberg, & Wilson, 1985) within a nonconcurrent multiple baseline design.

Baseline

The therapist randomly alternated presentations of one of the three target questions included in a condition. If the participant did not exhibit a correct response within 5 s, the therapist initiated the next trial. Contingent on a correct response, the therapist delivered praise and a highly preferred edible item.

Echoic prompt plus error correction

We used a progressive prompt-delay procedure during training. We conducted sessions at a 0-s prompt delay until the participant exhibited at least 90% correct prompted responses within a session. The therapist increased the delay to the prompt by 1 s each session (e.g., 1 s, 2 s, up to 10 s) if the majority (i.e., more than 50%) of the participant's incorrect responses was no response. That is, we did not increase the prompt delay by 1 s if the majority of the participant's responses were errors. Each trial included a sequence of steps: (a) Ask one of the questions, (b) wait the allotted prompt delay for a response, (c) deliver an echoic prompt if a correct response did not occur within the allotted prompt delay, and (d) wait 5 s for a correct prompted response. If the child did not emit a correct unprompted response during the trial, the therapist implemented error correction by repeating the trial sequence until the participant responded correctly prior to a prompt or the therapist repeated the trial sequence five times. However, only a correct unprompted response to the initial question in the trial is shown in the figure. During the initial sessions, the therapist provided a highly preferred edible item (identified from daily preference assessments) and praise following correct prompted and unprompted responses. After two sessions with a delayed prompt, correct unprompted responses resulted in praise and edible items and correct prompted responses resulted in praise only.

Tact prompt plus error correction

The procedures and consequences for correct responding were identical to the echoic prompt plus error correction condition, with one exception. Instead of providing an echoic prompt during an immediate prompt delay trial or when the participant did not engage in a correct unprompted response, the therapist presented a tact prompt by holding up a picture that corresponded to the correct response for 5 s. The therapist did not state the name of the item on the card at any point during the tact prompt. The error-correction procedures were identical to those described in the echoic prompt plus error correction condition except that we delivered tact prompts (a picture card and no vocal stimulus) instead of echoic prompts.

Cues-pause-point (CPP)

This procedure was similar to that described by McMorrow et al. (1987). Each trial contained two parts. In the first part of the trial, the therapist placed a picture corresponding with the correct response on the table in front of the participant, held up her pointer finger at eye level, and asked the participant a question. If the participant spoke prior to the therapist moving her finger, the therapist put her finger up to her mouth, said “shhh,” and placed her finger back at eye level. Once the child was quiet for approximately 2 s following the question or the prompt to remain quiet, the therapist moved her finger from eye level to point at the card on the table. If the child did not tact the picture on the table within 2 s, the therapist tapped on the picture with her finger for 3 s. Correct tact responses resulted in an edible item and praise. If the participant did not emit a correct tact response, the therapist provided an echoic prompt (e.g., said “cow”) and delivered an edible item and praise for correct prompted responding for only the first two sessions of this condition.

During the second part of the trial, the therapist presented the same question and conducted the trial in an identical manner to the first part, with one exception. The therapist placed a manila folder over the picture and pointed toward it. If the participant did not state the name of the picture card under the manila folder, the therapist delivered an echoic prompt.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

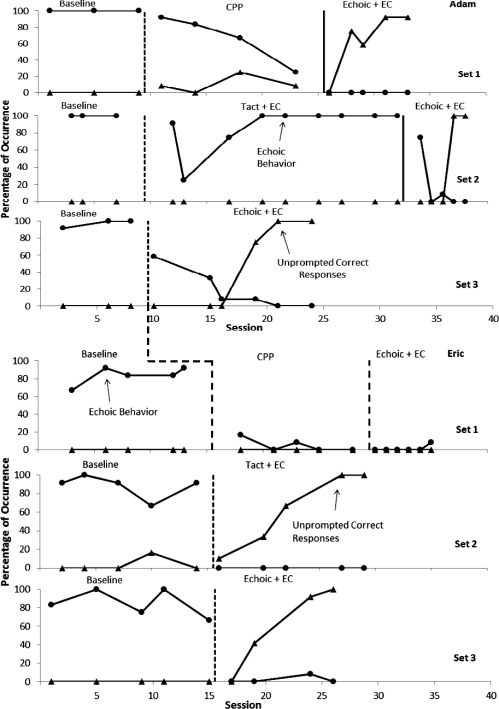

The results of the treatment comparisons are displayed in Figure 1. For both participants, only responding in the second portion of the CPP trial is depicted. During baseline, Adam did not emit any correct responses, and he frequently exhibited echoic behavior across the three stimulus sets. During the CPP condition (with Set 1), he exhibited low levels of correct responses, continued to exhibit echoic behavior, and began saying “shh” immediately prior to the correct response (e.g., “shh cow”). Therefore, we initiated the echoic prompt plus error correction and observed high levels of correct unprompted responding while his echoic behavior decreased. When we implemented the 0-s prompt delay in the tact prompt plus error correction condition (with Set 2), Adam did not exhibit correct responses and frequently exhibited echoic behavior. We then implemented echoic prompt plus error correction and observed high levels of correct unprompted responding and a decrease in echoic behavior. During the echoic prompt plus error correction condition (with Set 3), his correct unprompted responding increased, his echoic behavior decreased, and he met criterion performance in only six sessions. Overall, Adam's results indicate that echoic prompt plus error correction was the most effective treatment for increasing correct unprompted intraverbal responses and reducing echoic behavior.

Figure 1.

The percentage of occurrence of echoic behavior and unprompted correct responses for Sets 1, 2, and 3 for Adam (top three panels) and Eric (bottom three panels). CPP = cues-pause-point; EC = error correction.

During baseline, Eric rarely emitted correct responses and frequently exhibited echoic behavior across the three stimulus sets. When the CPP procedure was initiated with Set 1, he no longer emitted echoic behavior. However, he also did not emit the correct response following the tact prompt. Due to the absence of correct responding to the tact prompt in the CPP condition, we implemented the echoic prompt plus error correction treatment. However, Eric did not respond during this condition despite increasing the prompt delay to 10 s. Thus, the echoic prompt plus error correction condition was ineffective when initiated following CPP with Set 1. Eric's tact and echoic prompt plus error correction conditions (with Sets 2 and 3, respectively) produced mastery-level responding in a similar number of treatment sessions (i.e., five and four sessions, respectively) and an immediate decrease in echoic behavior. Overall, the results showed that tact and echoic prompt plus error correction produced mastery of intraverbal responses, although all of the treatments reduced his echoic behavior.

We extended previous research on intraverbal training by comparing the relative efficacy of three intraverbal training procedures, including CPP, a procedure that has been found to be effective for reducing inappropriate echoic behavior. Although the CPP procedure has been effective for increasing intraverbal behavior (McMorrow et al., 1987), we did not observe increases in correct intraverbals despite decreases in echoic behavior. One potential explanation for this finding is that components of the CPP procedure (e.g., “shh”) may have functioned as punishment for all vocal behavior, as evidenced by an immediate decrease in all vocal behavior following the implementation of CPP with Eric. A surprising finding was that the echoic prompt plus error correction condition was the most consistently effective training procedure. A potential explanation for this finding may be our use of an error-correction component. This component may have allowed additional opportunities for echoic behavior to come under appropriate stimulus control by differentially reinforcing echoic behavior only when it followed echoic prompts and not when it followed questions. By contrast, the tact prompt plus error correction and CPP conditions did not include the same opportunities because a correct prompted response occurred in the presence of a nonverbal stimulus (a picture) instead of a verbal stimulus.

This study contained some limitations that deserve comment. First, because we simultaneously manipulated several variables (e.g., prompt delay, type of prompt), the specific mechanisms that underlie treatment effects could not be determined. Second, because Adam's echoic behavior was on a decreasing trend, we could have extended the CPP procedure to determine whether increases in correct intraverbals would have emerged with further reductions in echoic behavior. Third, the effects of the echoic prompt plus error correction condition were not replicated with Set 1 for Eric. This replication failure may be due to prior exposure to an ineffective treatment (i.e., CPP) with these questions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elizabeth Gawley-Bullington and Keri Adolf for their assistance with data collection and Michael Kelley for his comments on this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Ingvarsson E.T, Hollobaugh T. An evaluation of prompting tactics to establish intraverbals in children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44:659–664. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMorrow M.J, Foxx R.M, Faw G.D, Bittle R.G. Cues-pause-point language training: Teaching echolalics functional use of their verbal labeling repertoires. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1987;20:11–22. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1987.20-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindelar P.T, Rosenberg M.S, Wilson R.J. An adapted alternating treatment design for instructional research. Education & Treatment of Children. 1985;81:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Verbal behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg M.L, Michael J. The benefits of Skinner's analysis of verbal behavior for children with autism. Behavior Modification. 2001;25:698–724. doi: 10.1177/0145445501255003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]